PRINCIPLE 6: WALK THE WALK – USING CONFLICT RESOLUTION TOOLS IN EVERYDAY LIFE

If we can resolve the little irritations, fears and challenges we have with the people we encounter on a day-to-day basis, we stand a chance of transforming those relationships. We may also avoid those irritations and challenges turning into long-term resentments. It is not an exaggeration to say that if we achieve that personally we become closer to being able to make peace in the world and create a different paradigm.

On this basis, it is critical for businesses and the people who work in them to be aware that our personal and corporate social responsibility starts with the level to which we take responsibility for our behaviour and conflicts at work and with the relationships we have with the people we engage with every day.

Walking the conflict resolution walk for individuals

As we set ourselves up as conflict resolution advocates and experts, we immediately come face to face with personal challenges. We cannot resolve other people’s conflicts if we are unwilling to look at our part in the conflicts we experience in our own life. We are forced to connect with those conflicts when we empathise with others and if we don’t we come across as ‘preachy’ and disingenuous. At the same time, acknowledging the conflicts in our own life can make us feel vulnerable if we cannot see a way through them or through our behaviour within them.

If we are to embark on becoming an agent for conflict resolution in any way we need to be willing to acknowledge the conflicts in our own life and be open to changing the way we respond and react to them. In so doing, we build our resilience and capacity to deal with difficult situations as well as becoming better placed to support others in conflict. When we start looking at our own challenges we generally come across the following stumbling blocks which come in the form of telling ourselves:

- I don’t have conflicts in my own life.

- I have so much conflict in my own life I’m never going to be able to help other people.

Generally neither of these are ever true. If we think that we don’t have conflict in our own life we are often trying to avoid it but other people around us will experience it and it is likely to surface when we least expect it. Equally, our vulnerability in our own conflicts and appreciation of how challenging they can be can be an asset in terms of our own knowledge, expertise and, crucially, capacity to empathise.

Case study

Anna and Belinda were sisters whose elderly parents were unwell and needed help with a number of aspects of their care. They had always been close but had chosen different paths in life. Anna had always spent more time with her parents than Belinda who had a senior management job in a multinational company.

Anna started calling Belinda every day to ask her to help and complained that Belinda was unhelpful. Anna sent Belinda email links of possible options of things to help their parents. Belinda made a policy of not responding to emails that were not clearly asking her to do something. She thought that Anna was making too much of a fuss about her parents and tended to not respond to Anna’s calls because she was too busy and found that they got on better the less contact they had.

This carried on for a number of years with no great consequence. Eventually Anna and Belinda’s parents died and they met at the house to talk about what needed to happen to organise probate. At the house Belinda noticed a pair of earrings that her mother had always promised her and asked Anna if she could take them. She was shocked when Anna who was usually very calm shouted at her and told her she was the most selfish, self-centred person she had ever met and she had never once made an effort to build bridges. This came as a huge shock to Belinda who was completely at a loss about how to deal with the situation and restore the relationship with her sister.

If we are too ashamed of the reaction to conflict we experience in our own life, we miss out on the opportunity to find help with those conflicts. We are also less able to support others resolve similar situations by virtue of the fact that we aren’t prepared to address them in our own life.

Case study

Johnny was a successful banker who was married with three young children. He had managed big teams and had always been praised and respected for the way he ran those teams and treated the people with them. Johnny’s wife had given up work since having their second child three years ago.

At his local church people often confided in Johnny and he always seemed happy and able to help. But when he was made redundant, Johnny started to lose confidence in himself. He was worried about how he was going to support his family and about what he was going to do with his life. Johnny spent a lot of time at home looking for a job. His wife got a job and Johnny took on more of the responsibilities around the house and with the children. However, he felt resentful that his wife could go out and work and he found it hard to cope looking after the home every day. He started to have a lot of arguments with his wife and became very critical with the children.

Johnny started to wonder how, if he couldn’t manage his own home life, he would be able to manage a team and go back to work. He felt like a fraud pretending to be a kind, capable person when in fact he felt like someone who couldn’t even communicate or be loving with his own family. His shame started to take over to such a degree that he stopped applying for jobs for three months thinking that any employer would ‘find him out’ and realise that he was not the kind caring person he appeared to be. Johnny finally got a job 9 months later three of which had been wasted in not applying.

When Johnny did return to work he found that he was more able to relate to and support colleagues who had been on maternity and sick leave and were returning to work. He became a champion for diversity within the organisation. Johnny’s strength was to acknowledge his management capabilities and the value they brought while at the same time accept that he had limitations and vulnerabilities. He found that when he started helping other people with their conflict situations in the knowledge that he struggled with these situations too, he began to learn from the support he provided and apply techniques that he used on or recommended to others in his personal life.

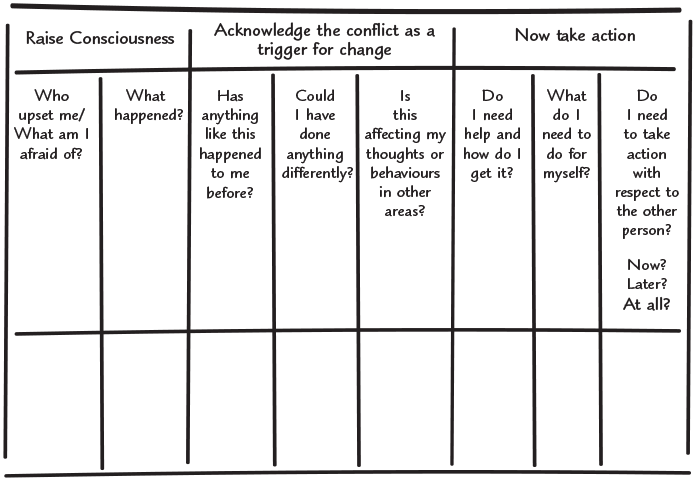

The CAN inventory

The CAN inventory provides a quick, personal check that we can run through daily to raise our Consciousness about the conflicts in our lives, Acknowledge them as potential triggers for change and growth and Now take action.

When we use the CAN inventory, we shine a light on those issues that we may prefer to brush over. Some people may question why we need to do that. Is that not turning something that was not a problem into a problem? The opposite is true, where we can tidy up the rough edges and resentments from our day, we can move through them and put them to bed. If we do not, they are more likely to build and create a snowball of blockages in the way we interact with other people and sometimes in the way we feel about and talk to ourselves. We become influenced in our decision-making without even knowing it and can therefore end up making poor decisions at work as a result of something going on at home.

Consciousness

Raising our consciousness involves us acknowledging and accepting that a fear (or a situation we have with someone else) exists and is disturbing us in some way. This stage does not require us to do anything about that situation other than accept its existence. We become more awake to it and its potential consequences and subsequently more alive to our part in it and what we might need to do about that.

Acknowledge

When we acknowledge the conflict as a potential trigger for change, we move into the mindset that this situation may lead us to a better place and that something good might come out of it. The reality is that when we make mistakes, our first response is not to celebrate them. Equally, when someone upsets us we are not inclined to thank them. However, if we can, we give ourselves an opportunity to change the dynamic, bring a lightness to the situation and often ensure that we do not find ourselves in the same situation again.

Now

The now in the taking action step emphasises that we must move on from simply acknowledging to being immediately willing to do something practical. We don’t need to take that action straightaway, rather we need to be willing to set those actions in gear.

Taking action is often the first thing we want to do before raising our consciousness and acknowledging the opportunities within the conflict. But it is more than likely that this action is going to be a reaction that feels slightly out of our control if we have not fully thought it through. Taking time with these actions can be much more powerful. For example, try to wait three days before responding to someone who has upset you before talking about it. In general, when we do this, we come from a much more empowered place and are better able to communicate our position, wants, needs and feelings.

Action can be interpreted in a number of ways. For example, I once heard someone say that meditation is the action of sitting still. Equally, action may include asking for help. The more we take time to take action, the wider our options start to become. The action does not always require us to speak to or engage with the other person – rather we might need to work on resolving it within ourselves. Finally, if we are thinking about taking action with respect to the other person, we should identify whether we need to take that action now, later or at all.

Walking the conflict resolution walk for businesses

As a business leader, ‘walking the walk’ might involve engaging with initiatives that are taking place within the community and supporting the development of early resolution skills as tools for leadership and management within the organisation.

When businesses engage with the community, they have more of an understanding of what goes on within it, and in turn communities find in local businesses a more accessible set of individuals than they had previously realised. This can start by businesses getting involved in initiatives that involve skills exchange where both members of the community and the businesses are valued for what they bring to the table. These initiatives almost have to start as an experiment. We never know how people are going to respond to each other in these situations, but where our starting point is a perspective of finding the win–win in these relationships there is a great deal of potential to build.

Case study

We trained a group of young people in early resolution skills and then took them into a corporate environment to demonstrate those skills. One would initially expect that the senior managers already had these skills. However, they were the first to admit that the listening techniques that the young people had demonstrated were different to the techniques that they used and gave them the opportunity to listen to and empathise with their clients and colleagues in a different way.

The process also allowed the senior managers to learn about the conflicts that young people were experiencing in the local community and enabled them to start thinking about how they could support the young people through work placements. This learning exchange was a forum for highly educated individuals to learn specific skills from local young people and those young people to be exposed to opportunities. The forum’s existence in and of itself immediately dissolved the feeling of ‘them and us’ and provided the opportunity to build community cohesion across groups that may not have previously come into contact with each other, deeper mutual understanding and opportunities for business and community growth.