26

Status Reports

“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do no know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

–Donald Rumsfeld

Status reporting is a typical upward communication done by an employee through an organization’s hierarchy. Even allowing for individual situations, it occurs fairly frequently—typically on a weekly basis. In this chapter, we will examine the intended purpose of a status report, present a structure under which to organize a status report, give you tips on whom to send a status report to and on how to decide the most appropriate frequency of status reports. We will conclude the chapter with some of the common pitfalls that we have seen in the area of status reporting.

Of course, status reporting need not be limited to just one’s managers and people higher up in the organizational chart. Project status reports can be also sent laterally to your fellow employees and even to outside stakeholders with whom you don’t have a hierarchical relationship. But in this chapter, we will look at it as a vehicle of communication with your management.

26.1 The Intended Purpose of Status Reports

To inform: Status reports are a means of keeping the relevant stakeholders informed about how a project is going on. This provides a communication channel between an employee and the management (typically his or her immediate manager). The people who need to know, need to be informed and status reports provide this opportunity.

To track progress against plan: Status reporting is done for a given period (typically a week). They provide a window to understand the progress not only in absolute terms, but also against what was planned for the period. This obviously implies that there was a plan in place for the period.

To provide a signal for any corrective action: When what is executed is not in line with what is planned, it calls for corrective action. Either the plan has to be changed or the execution has to be tightened. In any case, status reports provide the primary inputs for deciding such corrective action.

To act as an escalation channel and seek required action: When a status report is submitted, there could be some action that is sought from the recipients of the report. For example, an employee may have a persistent problem with a piece of hardware and the vendor has not responded back. This may need to be escalated via the management channel. Status reports provide a channel to seek such an escalation.

To highlight red alerts: During the course of a project, there may be some ‘red alerts’— those things that portend danger for the project and need corrective action from the upper levels of management. A status report should highlight such issues and give a heads up proactively, so that these can be addressed before extensive damage is done.

To outline the plan for the subsequent period: Just as the current period’s status report stacks up the progress vis-a-vis the plan set forth at the beginning of that period, the current status report should outline the plans for the coming period. This will provide continuity of communication and the project objectives.

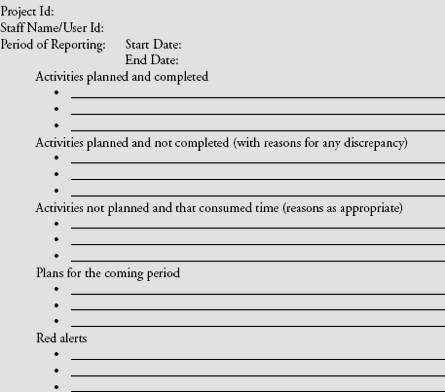

26.2 Organizing the Contents of a Status Report

In order for a status report to serve its intended purposes, it can be organized in the following simple heads:

- What was planned for this period and achieved? This would indicate things that are going as per plan.

- What was planned and not achieved? When this happens, it is important to perform a root-cause analysis of the deviation from the plan. When something that is planned is not achieved, it could either indicate a slippage or it could indicate that the original plan was unrealistic. In either case, some corrective action, that would include changing the plan, is needed.

- What was not planned and was accomplished or consumed time? If something that was not in the plan got done, it could either mean that there was some unexpected progress or that these unplanned activities that got done were simply unavoidable interruptions or unnecessary distractions. Again, in either case, it is necessary to understand why such interruptions happen and try to minimize these interruptions to make the plan as realistic as possible.

- What are the really critical issues (‘red alerts’) that need to be addressed? There may be some showstopper issues that the person writing the status report may become aware of. He should bring it to the attention of the manager by highlighting such issues. Examples of Such issues could be delays in getting hardware, unresolved problems in other modules, etc.

In addition to all this information about what happened over the previous tracking period, a status report should also give the plans for the next period. This part will act as the basis for the next report. Based on these, a sample template for status reports is given in Box 26.1.

26.3 Deciding the Recipients of a Status Report

The recipients of a status report must satisfy at least one criterion: They would need to know or be people who should act. The category of people who need to know would definitely include the direct manager of the author of the status report. It may also include others, depending upon the state nature of a project. For example, a project may be a high-visibility one for the senior management and top secret. For such a project, the highest levels of management, including the CEO, may be interested in the project’s progress. In such a case, it would make sense to copy the required levels on the original status report itself. Or else, it will have to wade through multiple levels of the management and the subject lines will be full of ‘Fwd: Fwd….’ to the extent that the CEO may not even be able to read the subject line on his screen (unless he opens the mail, which he won’t unless he feels the mail is important). A word of caution on this: It is worthwhile to get a clear understanding of who the recipients of a status report should be from your manager (or someone higher up) ahead of time. Don’t assume that your project is the super-project of the millennium for your company and copy all the CXOs.

For most common projects, the typical people who need to see the status report would include the direct manager and also the heads of the other groups who are either dependent on the status of the project or whose services the project needs (e.g., human resources or infrastructure).

The second category of people who need to receive a copy of the status reports would be people who should act based on the report. This again would include the immediate manager (as he would need to participate in most of the action!). In addition, this could include heads of other affected groups or dependent groups.

The recipients can change based on the stage in which the project is. For example, as a product approaches the release date, more people in several departments and at several levels (including the CXO) would need to be informed in a timely manner. It is a common practice to draw up a communication plan for a project right at the beginning, like the one given in Box 26.2.

26.4 What Should Be the Ideal Frequency of Status Reports?

The frequency of sending status reports depends on three factors:

- Duration/pace of project

- Current State of Project

- Nature of Project

The duration of a project is the primary driver to determine the frequency of status reports. The frequency of status reports should not be so rare that it does not add value to corrective actions. At the same time, it should not be so frequent that it is bureaucratic and not many changes happen between successive reports. For example, consider a six week project. At minimum, it may be required to have a status report twice in a week. This is necessary because, a considerable part of the project duration elapses (as much as 15 per cent) between reports if you have reports say once a week. This may be too long to implement any corrective action. If you have status reports as frequently as every day, it may be an overkill, because there would not be sufficient changes within a day and reporting every day would be construed as not adding much value. At the other extreme, consider a six month project. Then, once a week reporting should be more than sufficient.

Whatever be the duration of a project, each project typically goes through a crunch phase (normally towards the end of the project) wherein it is almost like a ultra-short duration project. For example, a six month release cycle for a product finally goes through a state close to ‘actual release date’. All hell breaks loose at this time and almost everyone in the organization is interested in what is happening in the project in an hour-by-hour basis - it is almost like the last five overs of a 50-overs cricket match. Status reports are expected very often at such a time. Such reports can be very informal, but they should provide the gist of the information as very senior people in the organization may be interested in such reports (see Snapshot 26.1).

Projects can be broadly classified into two types: First are the routine projects that an organization executes on a day to day basis. These could be the periodic releases of software products that a software organization produces; projects to improve production yields or production quality in a manufacturing organization and so on. The frequency of status reports in such projects is decided purely on the basis of the first two factors—nature and current state. But, there is the other category of projects— the pet projects of the ‘forces that be’ in the organization, the top secret projects that the bosses are personally overseeing, the high visibility launch that will rewrite the company’s history and because of which the bosses are breathing down your neck. For such projects that have high visibility or high stakes, all bets are off as to what should be the ideal frequency of reporting status. It could be very frequent—twice a week, daily or even hourly when the deadline is fast approaching. For such ad hoc status reports, be prepared to be flexible in format, content and media. These would be more of status updates than status reports. Be prepared to be creative in sending such updates by phone calls or even text messages/SMS.

Imagine you are watching a limited-overs cricket match in which the team batting second is chasing a target to win. At the beginning of the run chase, the ticker at the bottom may say something like ‘320 to win in 50 overs at 6.4 runs per over’. This information is updated every over for the first 20 or so overs. But, as we approach the last five overs, the same information is presented in a different form. Instead of Saying ‘37 to win from 5 overs at 7.4 runs per over’, the ticker shows ‘37 runs to win from 30 balls’. This is updated after every ball and not at the end of every over. The reason for the change in format of this ‘status report’ is that the runs-ball difference is a better abstraction of the status for the batting team to see how many dot balls they can allow or how many boundaries they have to hit. Similarly, it lets the bowling team set a field either to block boundaries or block singles. Also, the reason why the status report is updated after every ball and not after every over, is that there are only five overs (or 30 balls) remaining and every ball is crucial to take an appropriate and timely corrective action. It is easy to extrapolate this example to a real-life project in any industry. Crunch-time reporting calls for different formats and almost always a more frequent status reporting.

26.5 What Should the Recipients Do with a Status Report?

Understand and acknowledge the progress: The worst thing that can happen to a sender of a status report is that he feels like the reports are going into a blackhole with almost no responses from anyone receiving the report. While it is not fair to expect the recipient to respond to every status report, it would definitely undermine his credibility if he does not acknowledge the progress at least occasionally.

Know what actions need to be taken—and take them! Sometimes the writer of the status report may not explicitly express the action required of the recipient. The recipient (especially if he is the direct manager) should take some extra effort to understand the actions required of him. As the eventual goal of a communication cycle is acting on the message, taking the appropriate action is absolutely essential.

Get the antennae up for red alerts: When a certain item is marked as ‘red alert’, the manager should keep his antennae up for any further developments regarding that issue. A red alert has the potential to blow up and hence, requires extra communication over and beyond the periodic status reports. This extra communication can be in the form of unsolicited synchronous communication like face-to-face meetings and phone calls, through informal across-the-hallway conversations or even by tapping into the grapevine.

Be prepared to read between the lines and see through any sugarcoating: When an employee does not want to tell a piece of bad news explicitly, there may be some sugar-coating or beating around the bush. The recipient should be able to read between the lines, infer any ‘implied’ bad news and talk to the sender to explicitly clarify any such issues. Such issues, when unattended could potentially blow up.

26.6 Some Common Mistakes in Status Reporting

Making it look like a superman adventure: Sometimes a status report contains all the gory details of a problem and the heroic steps taken to solve it. This is a common mistake made by technical people when sending a status report to a boss who has grown up through the technical ranks, under the assumption that the boss would get impressed by such details. While it is possible that the boss is indeed interested in these details, these are needed only to the extent of making him take the required action. Status reports are neither the forum where one shows off technical adventurism nor one in which the boss proves he is still technically minded even after moving to management.

Not having the right level of abstraction: to take the previous point one step further, the status report is read by an audience who neither has nor needs the full level of detail that the writer of the report has. The audience needs a level of abstraction that is presumably at a higher level than what the writer has experienced. For example, a manager who receives a status report is primarily interested in two things: First, is the project going on track; second, if not, who should do what. In particular, what should he do to get the project back on track. If this level of abstraction is not provided by the writer of the status report, there is the risk of the manager taking an action that is completely tangential to what the writer intended.

Not having continuity between status reports of various periods: As discussed earlier, the status report for a given period tracks the progress against the plan for the previous period and also sets the agenda or plan for the coming period. Thus, there should be continuity across project reports. In the first chapter of this part of the book (Chapter 13), we saw that communication is an ongoing process and is made up of smaller communication cycles. Viewed this way, status reports form the communication cycles in the overall project communication. Not having continuity across the status reports and making each period’s status report focus on just that period’s burning fires or flash-in-the-pan achievements undermines the usefulness of status reports.

Sugarcoating: The writer of a status report should not shy away from giving any bad news that is there. Postponing giving the bad news is only going to make matters worse. Some people have an uncanny knack of telling bad news in such a way that no one understands that it is bad news, but at the same time the writer can later claim that he already mentioned it. Such sugarcoating or camouflaging will reduce the credibility of the writer. Bad news, if present, is better conveyed sooner than later. Delaying the revelation of bad news or sugarcoating it only postpones and magnifies an impending disaster. We deal with more of this in Chapter 29.

Copying multiple layers of hierarchy: Sometimes, the writer of a status report does not understand who all he should mark a copy of the status report to. ‘Just to play safe’, a copy of a status report may be marked to the manager, manager’s manager and even the CEO. This is perhaps the most unsafe option for several reasons. First, it unnecessarily clutters up the mail box of people at the senior management level. Second, the sender may be remembered by the senior management for the wrong reasons. In future, anytime the sender sends a mail to the senior management for a genuine reason, it may be ignored as yet another ‘play safe’ mail!

Having a red alert alive through several reporting periods: When a red alert continues to be alive over several reporting periods and if the project is progressing well, it would not be construed as a red alert at all! On the other hand, if the project is slipping and the red alerts continue to be flagged, then it means that appropriate corrective action has not been taken; either the manager or the person writing the report (or both) need to be held accountable for such a slip.

Not reading a status report and not following through on action items: The recipient of a status report (assuming that the report is sent to the right recipient) should carefully peruse the report, understand the action items expected of him and execute them within the timeframe agreed upon. A recipient (especially the manager) not following through with the action items will send a wrong message to the sender of the status reports that the reporting process is a bogus eyewash.

26.7 In Summary

Status reports tend to become a dreaded but necessary evil. While they are necessary, they need be neither dreaded nor evil. In order for a status report to be useful for the organization (or the recipients) and not intimidating for the writer of the report,

Use status reports as a vehicle to highlight accomplishments.

From the manager’s point of view, he would expect to know not just the good news, but also the bad news. If there is bad news, he’d better do what it takes to resolve the underlying issues. Resolution of An issue becomes more complex if the issue is allowed to stagnate for longer periods.

Sometimes what is bad news to you may not be recognized as bad news by your manager. And he may take an action entirely different from what you wanted him to take. Hence,

Don’t sugarcoat a problem; be explicit; propose possible solutions

Every problem is not a red alert. If everything is important, then nothing is important (at least for the manager). So,

Choose your targets correctly as far as red alerts are concerned.

As a recipient, a status report is not a mere tool to track progress against plan. A series of status reports can make interesting revelations about a project, a customer or an employee. So, as a manager receiving status reports,

Make sure you do some aggregate analysis of several status reports to spot trends.

Fig. 26.1