Chapter 9. Using ActionScript 3.0 Components

It’s entirely possible, of course, to produce Flash content without ActionScript. Even if not interactive, such content typically bears the visual distinction of compelling custom artwork, which is why the Flash authoring tool has appealed to designers and developers alike for years. When ActionScript does enter the equation, the creative possibilities extend even further, occasionally venturing into territory that, in recent years, has become the mainstay of Flex; namely, Rich Internet Applications (RIAs). When you develop content that requires sophisticated user input—for example, when input text fields aren’t enough, and you need radio buttons, combo boxes, and the like—the Components panel becomes your genie in a bottle. The Flash CS4 Professional ActionScript 3.0 component set, introduced in Flash CS3, is easier to skin and use, and performs more efficiently, than ever before.

Overview of the Component Set

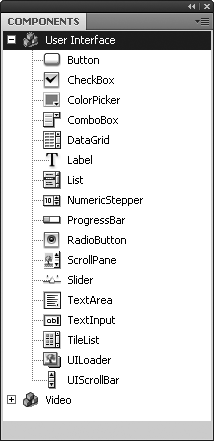

Out of the box, the Components panel (Window→Components) offers a handy number of predesigned

components—often informally called

widgets or controls—that provide

a wide range of features without the need for complicated programming. In

ActionScript 3.0 documents, these components are divided into two

categories: User Interface (UI) and Video, as seen in Figure 9-1. The UI group

contains numerous components comparable to HTML <form> elements, such as CheckBox, RadioButton, ComboBox, and Button. The Button component differs from button symbols in

that you can select and deselect it to switch it on and off, it has a

built-in disabled state, and shares other features consistent with the

component set as a whole. This group also contains useful components that

have no equivalent in HTML, such as ColorPicker, NumericStepper, and TileList.

The Video group contains the FLVPlayback component, used to deploy video files in Flash with drag-and-drop ease;

the FLVPlaybackCaptioning component,

which facilitates captioning for foreign language subtitles and the

hearing impaired; and numerous video-specific user interface components,

such as a standalone play button, mute button, and volume control

slider.

Increased Performance and Reduced File Size

The UI and Video components have been rewritten from the ground up in ActionScript 3.0, which lets them benefit from the same performance enhancements recounted throughout this book (in particular, see Chapter 4). This also means you can’t mix and match the components with those that were written for ActionScript 2.0. Fortunately, the Components panel automatically updates its choices depending on the version of ActionScript selected for the current FLA file. If you start in one version of ActionScript, add components to the stage or library, and then change the FLA file’s publish settings to ActionScript 3.0—or vice versa—you’ll see warning messages when you try to compile the SWF file, and the compile will fail.

The performance improvement for ActionScript 3.0 components is

substantial and can be demonstrated with a simple for loop, using practically the same code for

a side-by-side comparison between ActionScript 2.0 and 3.0 components.

Create a new ActionScript 2.0 FLA file, and then open the Components panel. Drag a copy of the

ComboBoxcomponent to the stage. Use the Property inspector to give this component the instance namemyComboBox.Select frame 1 in the Timeline, and then open the Actions panel. Enter the following ActionScript 2.0 code:

var startTime:Number = getTimer(); for (var i:Number = 0; i < 50000; i++) { myComboBox.addItem({label:i, data:i}); } trace((getTimer() - startTime) / 1000);In this code, a

startTimevariable performs the ActionScript equivalent to starting a stopwatch. Aforloop increments a numeric variable,i, from 0 to 49,999, which populates theComboBoxinstance with 50,000label/datapairs. Finally, the “stopwatch” is halted, and the result is converted to seconds and displayed in the Output panel.Select Control→Test Movie to review the length of time it takes your SWF file to display. Be prepared to wait several seconds! Your actual elapsed time may vary, depending on the speed of your computer, but in one series of tests, the code in Step 2 executes in 6.337 seconds.

The following steps demonstrate an equivalent test using the ActionScript 3.0 version of the same component.

Create a new ActionScript 3.0 FLA file, and then drag a copy of the

ComboBoxcomponent to the stage. Give it the instance namemyComboBox.Select frame 1 in the Timeline, and then enter the following ActionScript 3.0 into the Actions panel:

var startTime:int = getTimer(); for (var i:int = 0; i < 50000; i++) { myComboBox.addItem({label:i, data:i}); } trace((getTimer() - startTime) / 1000);This code is almost identical. In fact, the only change is the numeric variable typing, from

Numbertoint.Select Control→Text Movie to review the new elapsed time. Again, your actual results may vary, but in one series of tests, the ActionScript 3.0 version of this same component displayed in 1.419 seconds, which is a remarkable increase in speed.

In addition to working more efficiently, the components tend to add significantly less weight to SWF files than their ActionScript 2.0 counterparts. Table 9-1 shows a comparison of the components shared by both languages.

Component | AS 2.0 file size | AS 3.0 file size |

| 27KB | 15KB |

| 28KB | 15KB |

| 56KB | 35KB |

| 59KB | 40KB |

| 23KB | 14KB |

| 48KB | 29KB |

| 27KB | 15KB |

| 29KB | 18KB |

| 26KB | 16KB |

| 29KB | 16KB |

| 39KB | 22KB |

| 40KB | 21KB |

| 25KB | 15KB |

| 34KB | 18KB |

| 35KB | 57KB |

It’s important to realize that these file sizes aren’t cumulative.

In both ActionScript 2.0 and 3.0, each component shares its common

framework with other components in the component set for that language.

The biggest penalty comes with the first component’s file size;

additional components add only a small increase because they share most

of the programming framework already provided by the first component.

For example, the combined weight of the ActionScript 3.0 versions of Button and CheckBox is only 17KB—not the 30KB you might

expect—which is only 2KB more than either component alone.

Feature Changes

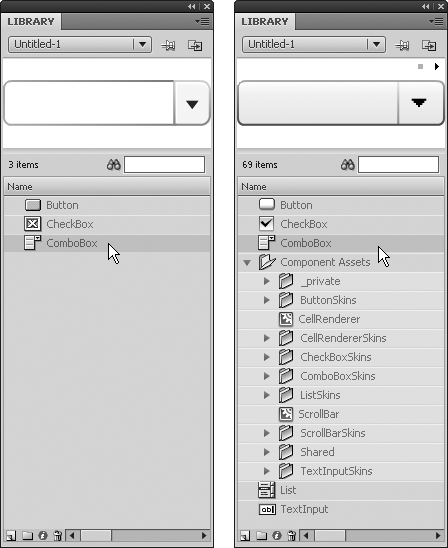

In ActionScript 2.0 documents, components are generally stored in

the Library as discrete entities. In ActionScript 3.0 documents, the

introduction of even a single component creates a new library folder

named Component Assets. This folder contains movie clip symbols used by

the components’ skins, and must not be deleted unless respective

components are purposefully removed from the FLA file (skinning is

discussed in greater detail in the sections “Styling Components with

Code” and “Skinning Components Manually” in this chapter). Figure 9-2 shows the same three

components—Button, CheckBox, and ComboBox—as dragged into an ActionScript 2.0

FLA file (left side) versus an ActionScript 3.0 FLA file (right side).

Note the Component Assets folder on the right, and note also that the

ActionScript 3.0 version of ComboBox

carries with it a copy of List and

TextInput, whose respective weights

are already included in the total file size for ComboBox.

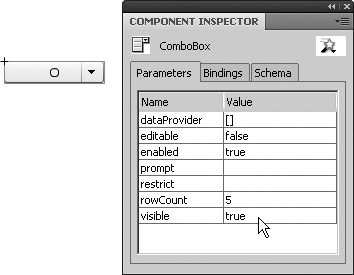

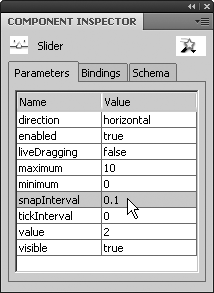

You can configure all components in the Component Inspector panel (Window→Component Inspector), as shown in Figure 9-3. Just select the component on the stage and arrange the settings as you please. In ActionScript 3.0 documents, the Bindings and Schema tabs of the Component Inspector panel are clickable, but their panes are disabled, as they apply only to data components, which are not compatible with ActionScript 3.0.

Because of the general event handling changes in ActionScript 3.0, the components are programmed somewhat differently from the ActionScript 2.0 set. For details, see the section Changes in Writing Code for Components later in this chapter.

Although it has an application programming

interface (API) and can be fully programmed like any other

component, the ActionScript 3.0 FLVPlayback component has been updated so that

its composition can be customized without any need for code.

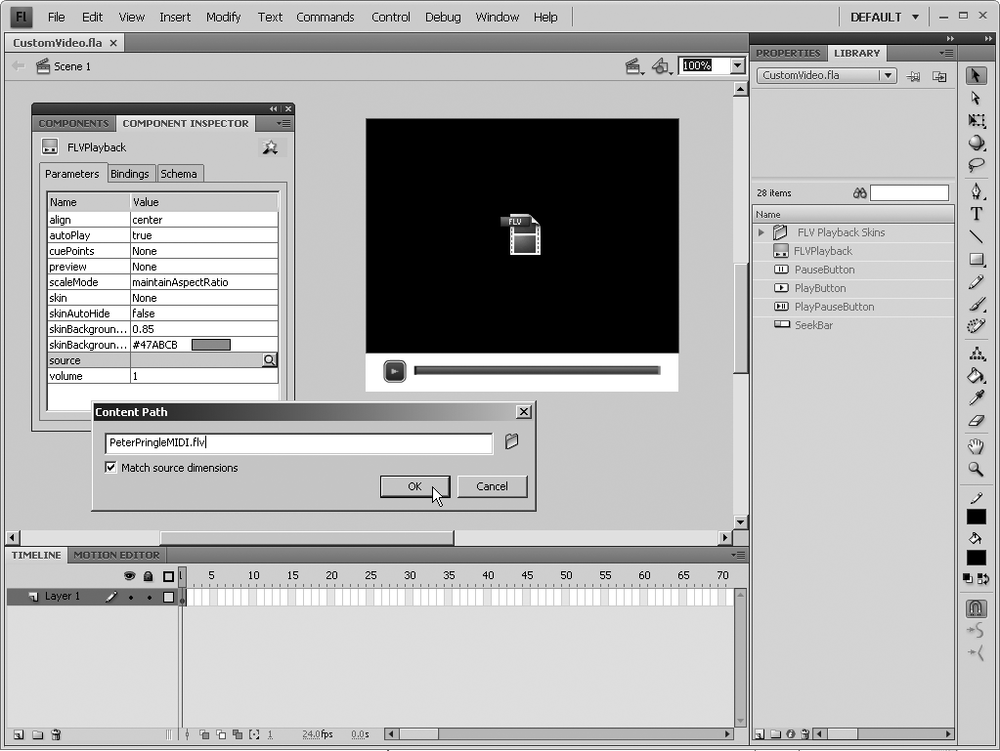

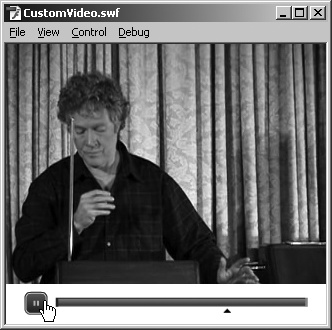

Create a new ActionScript 3.0 FLA file, and then open the Components panel. Drag a copy of the

FLVPlaybackcomponent to the stage. No instance name is necessary. Save this file as CustomVideo.fla, because you’re going to use it again later in this chapter.Select the Component Inspector panel, and then ensure that the

skinproperty is set toNone. You don’t need a skin in this case, because in the next step you’ll be supplying a pair of individual skin elements to customize video playback features.Drag a copy each of the

PausePlayButtonandSeekBarcomponents, and position them on the stage wherever you prefer. If you like, change the dimensions of the FLA file to match the surface area taken up by these components. None of the components requires instance names.With the

FLVPlaybackcomponent selected, use the Component Inspector panel to set thesourceproperty to an FLV file, as shown in Figure 9-4. Click OK to close the Content Path dialog box.Select Control→Test Movie to verify that the

PausePlayButtonandSeekBarcomponents do indeed control video playback, even without the use of ActionScript or instance names (Figure 9-5).

New and Removed Components

Flash CS3 introduced six components for use in ActionScript 3.0

documents that remain available in Flash CS4: ColorPicker,

Slider, TileList, FLVPlaybackCaptioning, CaptionButton, and FullScreenButton. These components are

demonstrated in the section Changes in Writing Code for Components later in this chapter.

In conjunction with these additions, a number of previously available

components have been removed, which only happens when a FLA file is

configured for ActionScript 3.0. The removed items consist of the

non-visual data components, including XMLConnector and WebServiceConnector; the media components,

superseded in Flash 8 by FLVPlayback;

and the following UI components: Accordion, Alert, DateChooser, DateField, Menu, MenuBar, Tree, and Window.

Note

The media components are actually intended for ActionScript 1.0 but still function in ActionScript 2.0 documents. They are not, however, compatible with ActionScript 3.0.

The full list of authoring tool components for ActionScript 2.0 and 3.0 is shown in Table 9-2, Table 9-3, Table 9-4, and Table 9-5.

Component | AS 2.0 | AS 3.0 |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | |

| X |

Component | AS 2.0 | AS 3.0 |

| X | Superseded by |

| X | Superseded by |

| X | Superseded by |

Component | AS 2.0 | AS 3.0 |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X (renamed |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X |

Component | AS 2.0 | AS 3.0 |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

| X | X |

Note

For details on how to work around many of the missing components in ActionScript 3.0 documents, see Chapter 10.

Changes in Writing Code for Components

Thanks to the improved event-handling model in ActionScript 3.0,

writing code for the component set is as straightforward as any of the

event handling examples illustrated in other chapters of this book. Like

movie clip symbols and button symbols, components inherit from

the EventDispatcher class,

which means they all support the addEventListener() method that lets you

associate an event with a custom function that responds to that event. The

similarity among the following examples underscores the consistency

inherent throughout the ActionScript 3.0 API. These examples demonstrate

how to use the UI components that weren’t available in versions of the

authoring tool prior to Flash CS3.

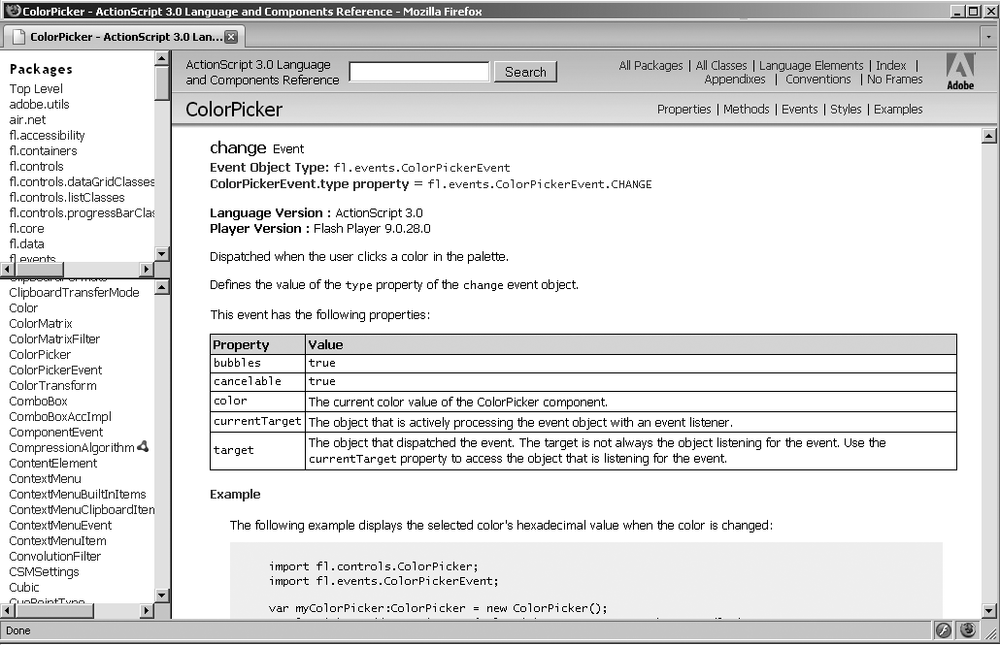

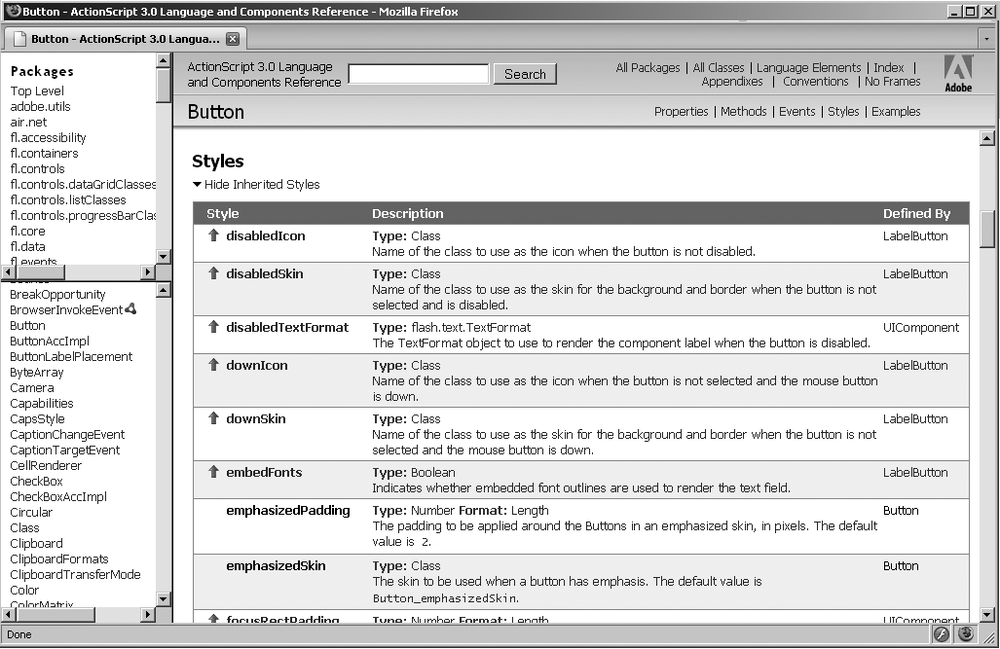

Until you get familiar with a particular component, your first step

in programming one should always be to consult its class entry in the

ActionScript 3.0 Language and Components Reference, available at a

moment’s notice from the documentation (Window→Help), which opens in a

browser window. A class entry’s Events summary, in particular, lets you

know immediately what events a component supports, as well as what data

type the event belongs to. For example, the ColorPicker class entry features a change event. Clicking on the hyperlink for this event indicates that the

event is referenced by way of the ColorPickerEvent class, as seen in Figure 9-6.

All the components reveal their secrets in this way, so you can easily program them. In all cases, the parameters shown in the Component Inspector panel correspond to properties of the component’s class. Properties may be configured in the panel, with ActionScript, or a combination of both.

ColorPicker

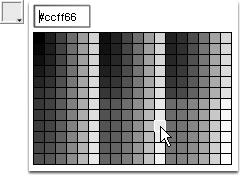

The ColorPicker component

displays a clickable color chip that expands into a

configurable color palette that lets you select a color or type in a

color (Figure 9-7).

Assuming a ColorPicker component on

the stage with the instance name myColorPicker and a movie clip with the

instance name myMovieClip,the following

ActionScript handles the selection of a color from the component’s

configurable color palette:

import fl.events.ColorPickerEvent;

var myColor:ColorTransform = new ColorTransform();

myColorPicker.addEventListener(ColorPickerEvent.CHANGE, ¬

changeHandler);

function changeHandler(evt:ColorPickerEvent):void {

myColor.color = myColorPicker.selectedColor;

myMovieClip.transform.colorTransform = myColor;

}The ColorPickerEvent class must

be imported, even in a frame script, because it isn’t part of the

flash package. A myColor variable is declared and set to an

instance of the ColorTransform class,

waiting to be used in response to a change event from the component. The operative

code here is the addEventListener() method, which

associates the ColorPickerEvent.CHANGE event constant with a

custom changeHandler()

function.

The changeHandler() function

sets the color property of the

myColor instance to the currently

selected color, and is then assigned to the colorTransform property of a movie clip with

the instance name myMovieClip. All DisplayObject objects, including

movie clip symbols and sprites, support color transformation in this

way.

The color palette of the ColorPicker component is fully customizable,

and can display up to 1,024 colors. To have the myColorPicker instance display red, white, and

blue, simply assign an array of hexadecimal values to the ColorPicker.colors property:

myColorPicker.colors = new Array(0xFF0000, 0xFFFFFF, 0x0000FF);

Slider

The Slider component provides a slider with a draggable knob that optionally

snaps to a configurable range of values (Figure 9-8).

As Figure 9-9 indicates,

the Slider component can be displayed

horizontally, but is easily set to a vertical orientation by a change to

the direction parameter (the first

entry in the Name column). Numerous other parameters are available. The

liveDragging parameter determines how

often Slider dispatches its change event. When liveDragging is set to true, SliderEvent.CHANGE is dispatched while the

knob is dragged, as often as the Slider.value property updates. When set to

false, the SliderEvent.CHANGE event is dispatched only

when you release the knob.

The maximum and minimum parameters define the component’s

range of selectable values, and snapInterval determines the rate at which

snapping should occur. The tickInterval parameter determines the

distribution of visible tick marks, and value determines the starting position of the

knob.

Warning

According to the Slider class

documentation, a snapInterval value of 0 is

supposed to mean continuous dragging, but this isn’t what actually

happens. In a range from 0 to 10, a snapInterval value of 1 snaps the knob to the values 0, 1, 2, 3,

etc. A value of 5 snaps the knob to

the values 0, 5, and 10. To achieve continuous dragging, enter a very

small value, such as 0.1.

The following ActionScript shows the Slider component as a volume slider, assuming

its range is set from 0 to 1. The volume setting is taken from the Slider.value property (see code in

bold):

import fl.events.SliderEvent;

var mySound:Sound = new Sound();

mySound.load(new URLRequest("sampleSong.mp3"));

var myChannel:SoundChannel = mySound.play();

var myTransform:SoundTransform = new SoundTransform();

mySlider.addEventListener(SliderEvent.CHANGE, changeHandler);

function changeHandler(evt:SliderEvent):void {

myTransform.volume = mySlider.value;

myChannel.soundTransform = myTransform;

}A Sound instance is associated

with a SoundChannel instance, which

makes it available to volume transformations. Here again, the actual

event handler is very simple: the SliderEvent.CHANGE event is associated with a

custom changeHandler() function, which

invokes the Slide.value property on

the mySlider instance in order to

update the volume property of a

SoundTransform instance that, in

turn, updates the volume of the Sound

instance.

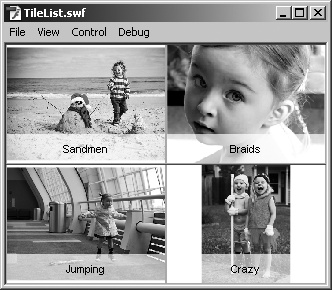

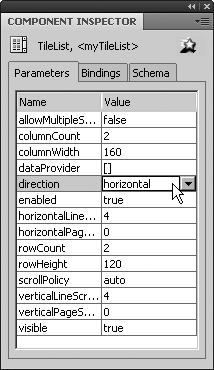

TileList

The TileList component is

comparable in some ways to an HTML table or a simplified version of the

DataGrid component. In a nutshell, it

provides a grid of rows and columns to display images (Figure 9-10).

Like the Slider component, the

properties of TileList are easy to

configure in the Component Inspector panel (Figure 9-11). The columnCount and rowCount parameters determine the

number of columns and rows in the grid, respectively, while columnWidth and rowHeight determine their dimensions. The

direction parameter specifies whether

images progress sequentially across or down the grid before wrapping.

Scrolling is configured with scrollPolicy parameter, which you can set to

auto, on, or off.

The following ActionScript produces the 2 by 2 grid shown in Figure 9-10:

myTileList.addItem({label:"Sandmen", source:"sandmen.jpg"});

myTileList.addItem({label:"Braids", source:"braids.jpg"});

myTileList.addItem({label:"Jumping", source:"jumping.jpg"});

myTileList.addItem({label:"Crazy", source:"crazy.jpg"});

myTileList.addEventListener(Event.CHANGE, changeHandler);

function changeHandler(evt:Event):void {

trace(myTileList.selectedItem.label);

}Note that the change event for

this component comes directly from the Event class, which means no import directive is necessary in frame scripts

that handle TileList events.

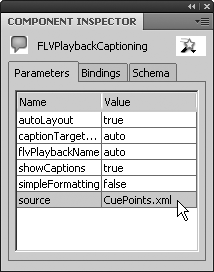

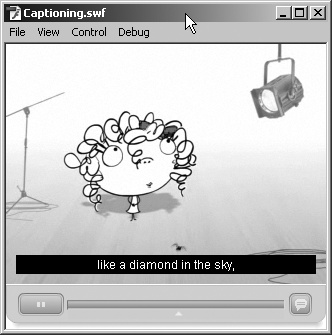

FLVPlaybackCaptioning and CaptionButton

Video subtitles and captions have been possible for several

releases of Flash, but until the FLVPlaybackCaptioning component, introduced in

Flash CS3, they required custom programming. In ActionScript 3.0

documents, you can now add captioning to your videos without code.

You do need an XML document that adheres to the World Wide

Web Consortium’s (W3C) specification for TimedText (TT) documents

(http://www.w3.org/AudioVideo/TT/). The CaptionButton component selects and deselects

captioning. Here’s an example of a TimedText XML document:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="iso-8859-1"?>

<tt xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2006/04/ttaf1"

xmlns:tts="http://www.w3.org/2006/04/ttaf1#styling">

<head>

<styling>

<style id="1" tts:textAlign="left"

tts:fontFamily="Arial" />

<style id="2" tts:textAlign="center"

tts:fontFamily="Arial" />

</styling>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<p begin="00:00:09.50" dur="1000ms" style="1">

Okay, action!</p>

<p begin="00:00:11.00" dur="2800ms" style="2">

Twinkle, twi ... le</p>

<p begin="00:00:15.50" dur="1500ms" style="1">

Okay, action!</p>

<p begin="00:00:17.50" dur="4600ms" style="2">

Twink ... le ... tink [hiccup]! Oh!</p>

<p begin="00:00:22.75" dur="2100ms" style="1">

Okay, action!</p>

<p begin="00:00:25.75" end="00:00:29.25" style="2">

Twinkle, twinkle, little star</p>

<p begin="00:00:29.75" end="00:00:32.50" style="2">

how I wonder what you are</p>

<p begin="00:00:33.00" end="00:00:36.00" style="2">

bup bup bup ... world so high,</p>

<p begin="00:00:36.50" end="00:00:39.00" style="2">

like a diamond in the sky,</p>

<p begin="00:00:39.50" end="00:00:40.00" style="2">

Oh!</p>

<p begin="00:00:41.25" end="00:00:41.75" style="2">

Oh dear.</p>

<p begin="00:00:42.25" end="00:00:43.25" style="1">

Action!</p>

<p begin="00:00:43.50" end="00:00:47.00" style="2">

[sproing! sproing! sproing!]</p>

<p begin="00:00:48.00" end="00:00:53.00" style="2">

How I wonder what you are. Bup!</p>

<p begin="00:00:54.00" end="00:00:55.50" style="2">

Buh buh buh, oh ...</p>

<p begin="00:00:56.00" end="00:00:57.00" style="2">

Buh buh, oh ...</p>

<p begin="00:00:57.50" end="00:00:58.50" style="2">

Nooo!</p>

</div>

</body>

</tt>Note that a <styling>

element, nested in the <head>

element, allows for the declaration of styles—here, left- and

center-alignment—that can be referenced by an id attribute later in the body of the

document. Note, also, the alternate ways to specify the duration of a

caption, including collaborative begin and dur attributes, such as begin="00:00:09.50" dur="1000ms", and

collaborative begin and end pairings, such as begin="00:00:25.75" end="00:00:29.25". Once a

TimedText document is prepared, the process of captioning is

trivial.

Drag a copy of the FLVPlayback

and FLVPlaybackCaptioning components

to the stage. Neither component needs an instance name. FLVPlaybackCaptioning becomes

invisible at runtime. Position it where you like.

Use the Component Inspector panel to configure the skin

parameter of the FLVPlayback

component to None or to one of the

skins with the word “Under” in the name, like SkinUnderPlaySeekCaption (this is important

because skins with “Over” in the name obscure the captioning text

field). Set the source parameter to a

video file that correlates with the TimedText document.

Select the FLVPlaybackCaptioning component, and then set its source

parameter to the location of the TimedText document, as shown in Figure 9-12.

At runtime, captions are automatically transferred from XML format

to visual display, as seen in Figure 9-13. The CaptionButton component is built-in to any

skin whose name contains the word “Caption” and allows the user to

select and deselect captions. If no skin is selected, captions are displayed by default.

The CaptionButton component can also

be used on its own, apart from any skin, in the same manner described in

the FLVPlayback exercise in the Feature Changes of

this chapter.

FullScreenButton

The FullScreenButton component

exists as a built-in element of several of the provided skins for the

FLVPlayback component, as well as a

standalone component used with FLVPlayback. Ultimately, the FullScreenButton component is just a button

that invokes the FLVPlayback.enterFullScreenDisplayState()

method. To demonstrate its use, you have to view the SWF file and video

content in a properly configured browser window.

Open the CustomVideo.fla file created in this chapter’s Feature Changes, and then resave it as FullScreenButton.fla.

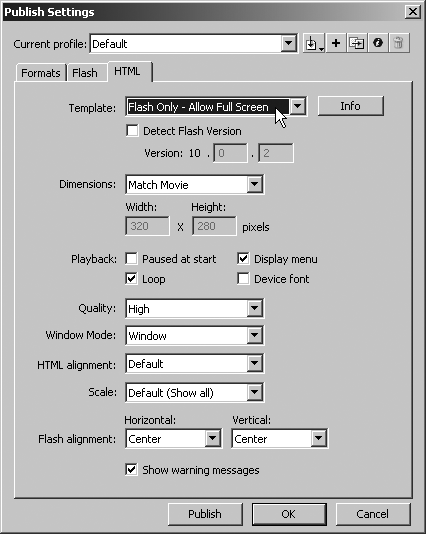

Open the Components panel, and then drag a copy of the

FullScreenButtoncomponent to the stage. No instance name is necessary.Select File→Publish Settings→HTML, and then change the Template drop-down list to “Flash Only - Allow Full Screen,” as shown in Figure 9-14.

The selection of this template automatically inserts crucial lines of code in the HTML that embeds the SWF file, although the addition can certainly be made by hand. If you prefer to work manually, you have to add a new

<param>element inside the existing<object>element to explicitly permit full-screen viewing (new code in bold):<object><param name="allowFullScreen" value="true" />then add a corresponding attribute to the companion

<embed>element:<embed src="FullScreenButton.swf" ...

other attributes... allowFullScreen="true" ... />These additions must be mirrored in the JavaScript function that appears in the same HTML document.

Select File→Publish Preview→HTML to launch the SWF file in a browser. Click the

FullScreenButtoncomponent to see the video display in full-screen mode (Figure 9-15). Press the Esc key at any time to exit full-screen mode.Note that during full-screen mode, the video UI controls are hidden from view. This happens because the

FLVPlayback.fullScreenTakeOverproperty is set totrueby default.

Close the SWF file. Select the

FLVPlaybackcomponent on the stage, and then use the Property inspector to name itmyFLVPlayback. Select frame 1 in the Timeline, and then open the Actions panel. Enter the following code:myFLVPlayback.fullScreenTakeOver = false;

Select File→Publish Preview→HTML once again to launch the SWF file in a browser. Note that this time, the components remain visible in either mode (Figure 9-16).

Changing the Appearance of Components

The standard look and feel of the ActionScript 3.0 component set can be freely changed, a procedure called styling or skinning, depending on how you go about it.

Styling Components with Code

The StyleManager class lets you

reference special styling properties—called styles—for each component.

For example, in the Help menu’s ActionScript 3.0 Language and Components

Reference, if you consult the class entry for the Button component, you find that in addition to

Public Properties, Public Methods,

and Events summaries, the Button

class also features a summary for Styles, as seen in Figure 9-17. Make sure to always

click “Show Inherited Styles” to see them all.

One of these styles (not shown in Figure 9-17) is called textFormat, which makes a quick and useful

demonstration of two StyleManager

methods.

Create an ActionScript 3.0 FLA file, and then open the Components panel. Drag a copy of the

ButtonandCheckBoxcomponents to the stage.Select frame 1 in the Timeline, and then open the Actions panel. Enter the following code:

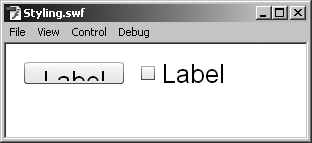

import fl.managers.StyleManager; import fl.controls.Button; import fl.controls.CheckBox; var myTextFormat:TextFormat = new TextFormat(); myTextFormat.size = 26; StyleManager.setStyle("textFormat", myTextFormat);The

StyleManager,Button, andCheckBoxclasses must be imported, even in frame scripts, because none of these classes belongs to theflashpackage. AmyTextFormatvariable is declared and set to an instance of theTextFormatclass, and then has itssizeproperty set to 26. Finally, the staticStyleManager.setStyle()method is invoked, with"textFormat"as the first parameter, and themyTextFormatinstance as the other. The"textFormat"parameter is a string that refers to thetextFormatstyle that both of these components happen to share.Select Control→Test Movie to experience a font size that’s too large for the current dimensions of the components (Figure 9-18), showing that the

setStyle()method applies styling to all components in a document that feature thetextFormatstyle.Close the SWF file, and then return to the Actions panel. Update the existing ActionScript so that it looks like this (changes in bold):

import fl.managers.StyleManager; import fl.controls.Button; import fl.controls.CheckBox; var myTextFormat1:TextFormat = new TextFormat(); myTextFormat1.size = 26; var myTextFormat2:TextFormat = new TextFormat(); myTextFormat2.size = 8; StyleManager.setStyle("textFormat", myTextFormat1); StyleManager.setComponentStyle(Button, "textFormat", ¬ myTextFormat2);

This time, two

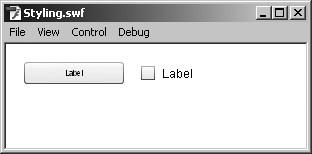

TextFormatinstances exist. The first one, as before, is fed into theStyleManager.setStyle()method, and updates thetextFormatstyle of both components. The second one, which was configured with a smaller font size, is fed into theStyleManager.setComponentStyle()method, which accepts one additional parameter; namely, the class name of one of the components,Button. This second method overrides the global formatting established by thesetStyle()method, because it calls out a particular component type by name.Select Control→Test Movie again to verify that the

Buttoncomponent now has a much smaller font size (Figure 9-19).Close the SWF file again. You’ve seen how to affect the styling of all components in a document, and you’ve also seen how to affect the styling of all of one type of component. The final way to stylize components is to invoke the

UIComponent.setStyle()method, which is inherited by each component individually. Select theCheckBoxcomponent, and then use the Property inspector to give it the instance namemyCheckBox. Return again to the Actions panel, and then update the existing code so it looks like this (changes in bold):import fl.managers.StyleManager; import fl.controls.Button; import fl.controls.CheckBox; var myTextFormat1:TextFormat = new TextFormat(); myTextFormat1.size = 26; var myTextFormat2:TextFormat = new TextFormat(); myTextFormat2.size = 8; var myTextFormat3:TextFormat = new TextFormat(); myTextFormat3.size = 12; StyleManager.setStyle("textFormat", myTextFormat1); StyleManager.setComponentStyle(Button, "textFormat", ¬ myTextFormat2); myCheckBox.setStyle("textFormat", myTextFormat3);

A third

TextFormatinstance has been added, this one routed specifically to themyCheckBoxinstance, via its inheritedUIComponent.setStyle()method. The original size-26 formatting is still in effect, but theButtoncomponent overrides it, thanks to its more specifically honedmyTextFormat2instance. Here, theCheckBoxcomponent also overrides it, thanks to its even more specifically honedmyTextFormat3instance.Select Control→Test Movie one last time to verify that the

CheckBoxcomponent now features a practically normal-sized font (Figure 9-20).

The textFormat style isn’t the

only property available, of course. Many components feature an icon style, for example, that lets you

incorporate a small image into the component’s display. Consult the

class entry of the component(s) in question, and have fun

experimenting!

Skinning Components Manually

It goes without saying that some design choices are more successful when implemented manually. Changing the actual make-up of a component’s skin—that is, redrawing or manipulating the actual movie clips that comprise a component’s features—is called skinning, and from a designer’s standpoint, it couldn’t be any more intuitive than the following steps.

Create a new ActionScript 3.0 FLA file, and then open the Components panel. Drag a copy of the

Buttoncomponent to the stage.Double-click the

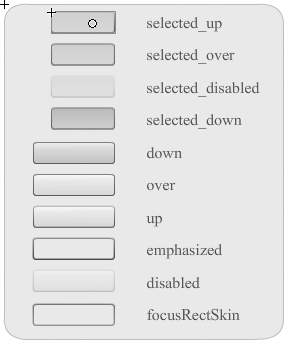

Buttoncomponent on the stage, just as you would to edit in place any movie clip symbol. Doing so opens the component into an “exploded view” that reveals each element of its default skin, as seen in Figure 9-21.

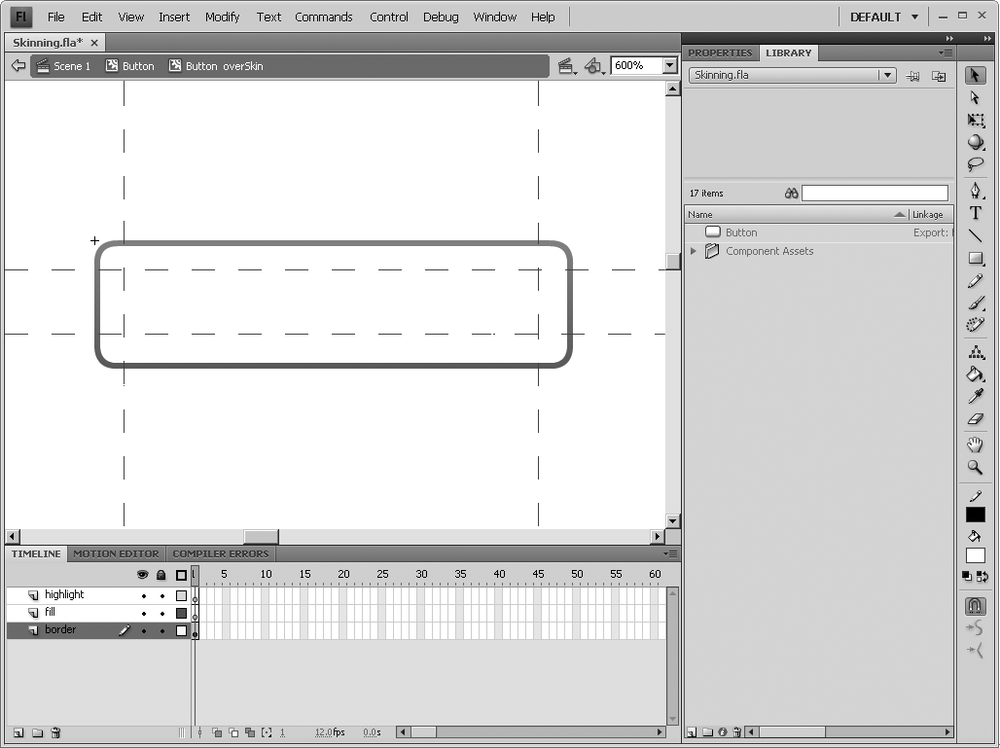

Double-click the representation of the

overstate to enter the timeline of that element. Most component skins take advantage of 9-slice scaling, as seen in Figure 9-22. The dashed lines indicate which portions of the image will scale when resized and which portions won’t. In Figure 9-22, the corner regions maintain their present aspect ratios, while the top, bottom, and sides stretch as necessary.Individual component skins may vary, but you’ll typically find a number of timeline layers already in place. Here, these include layers named

highlightandfill. Carefully select the content of these layers, and then delete it. Select the Paint Bucket tool, choose a markedly different fill color, such as pink, and then click inside theborderlayer stroke to fill the rounded rectangle.Select Edit→Edit Document to return to the main timeline. Drag another copy of the

Buttoncomponent from the Library to the stage.Select Control→Test Movie, and then move your cursor over and away from both

Buttoncomponents to verify that their over states have visually changed.