CHAPTER

5

The Compassionate Connected Caregiver

IN JUNE 2017, my daughter-in-law, Olivia, experienced excruciating abdominal pain that came on unexpectedly and wouldn’t go away. She went to the emergency room twice over the course of a week. Each time, she waited for well over an hour to see a doctor and then longer for diagnostic testing, wasting the better part of a day. All the diagnostic tests—including CT with contrast, ultrasounds, and lab work—came back negative. And yet she still felt tremendous pain, an 8 out of 10. The doctors gave her the narcotic hydrocodone, but Olivia didn’t want to take it. She was a paramedic and couldn’t work shifts while the drug was in her system. Unfortunately, she had no choice. The pain was that bad.

A couple of nights after her second ER visit, Olivia and her wife (my daughter Hilary) came to our house for dinner. Before we could sit down to eat, Olivia had to go home to lie down because her stomach hurt so bad. She called a bit later saying she couldn’t stand it anymore and had to get some kind of relief. Olivia had scheduled an appointment with a GI specialist, so Hilary called the nurse on call for the GI provider. As it was after hours on a Sunday, the nurse told them to go back to the ER. So they did, with me in tow.

When we arrived, it was 8:55 in the evening, and Olivia was clutching her abdomen and rocking back and forth in pain. She had gone pale, and she was scared. Hilary was angry—it was Olivia’s third time in the ER in less than a week, and nobody had taken care of her wife’s pain or given them any answers. Over a half hour later, the triage nurse finally saw Olivia. Taking her vital signs, he apologized and announced that he would have to send them back out to the waiting area. “How much longer before we can see a doctor?” she asked.

“Between now and the end of time,” the nurse responded. “We just never know what’s coming in.”

I’m sure the nurse was feeling stressed out and overwhelmed by the workload. Hour after hour, he had to deal with any number of frustrated patients. Still, we didn’t appreciate his flippant remark, and in a small way, it caused suffering. The nurse may have been technically correct in saying that the ER staff “never knew what was coming in,” and he might have felt better letting us know that our long wait wasn’t his fault. But the comment and the way it was delivered only engendered further fear, anxiety, and anger at a process that was beyond our control.

For the next two hours, we sat in the waiting room without so much as an update. People around us were in severe pain, moaning and crying out. Some were angry, and at least one patient was accompanied by two security guards. The ladies’ restroom was filthy—I’ll spare you the details—and the soap dispensers were all empty.

Finally, just before midnight, a nurse whom I’ll call Cathy came in to interview and assess Olivia. She tried taking her blood pressure, but the machine wasn’t working, so she went to get another. It took another 20 minutes for her to reappear (without a new machine) and announce that a Dr. Edelman (not his real name) would see her.

Five minutes after that, Dr. Edelman came in. He was a young physician, very personable. Holding out his hand, he introduced himself by his first name, Jim. He empathized with Olivia about the long wait and apologized for it. Then he conveyed that he understood Olivia’s frustration at having come to the ER three times without receiving any answers or pain relief. He leveled with Olivia, saying, “I can do more tests, and I’ll be sure that we haven’t missed anything. Unfortunately, I can’t get you answers tonight. But we’ll do everything we can to make sure you’re comfortable.” He went away for a few moments, and upon returning, he admitted that Olivia probably should have been put on Protonix for potential gastritis. He ordered an IV for her and sent her home later with a prescription to fill. Overall, we all found Dr. Edelman extremely kind. He had made us feel safe in his care, and in the course of a very short interaction, he had connected with us. As we left the hospital, I found myself thinking, Why don’t all caregivers do this?

The Reduction of Suffering Starts with Us

All caregivers can reduce suffering, and with the Compassionate Connected Care model in hand, my hope is that more of us will. The patients and caregivers in our study provided us with a wealth of insight into specific behaviors that caregivers can practice, master, and deploy in their work to help avoid or mitigate patients’ suffering. These behaviors—which as we saw in the last chapter include connecting with them, acknowledging suffering, providing autonomy, and so on—are not rocket science. Any of us can perform them. In fact, many of us already are. The problem is that we’re not adopting these behaviors consistently or effectively enough to improve patient and caregiver experience as reflected in the quantitative and qualitative surveys.

In many ways, our failure to achieve consistency and excellence in these behaviors reflects the broader context in which caregivers work. As we’ll explore in later chapters, our cultures don’t always support these behaviors, and our organizations don’t “operationalize” them by providing adequate staffing, resources, and encouragement. But there’s another reason we don’t always behave in ways that prevent or alleviate suffering. Existing change initiatives designed to foster these behaviors tend to falter due to a misplaced emphasis on tactics rather than purpose.1 At staff meetings, leaders often stand before teams and say: “Our scores on responsiveness are terrible! We’re in the thirtieth percentile, and corporate has given us a goal of the eightieth percentile. We have to step it up!” Team members hear that the team has to improve to meet a goal that corporate has set. Is that really a compelling rallying cry?

Imagine if leaders were to say, “Listen, our patients are telling us that they don’t feel like we are responsive enough and that we might be making them wait too long before we respond to their needs. What do you think we could do to help our patients feel like we were more responsive to their needs?” Now team members would perceive that they need to figure out how to help patients feel like their needs are being met. The need to work on behavior would seem more meaningful, connecting with the “why” of work—the larger purpose that caregivers are seeking to accomplish in their careers.

What we need, then, aren’t more metrics-focused initiatives. We need specific strategies that individual caregivers can use that bring them closer to purpose. In this chapter, I present a few such strategies—simple, easy techniques that caregivers can try in their daily work. These strategies aren’t the only techniques that will work, but they will help caregivers do more of what we know makes a difference to the people for whom we care and to our colleagues. If caregivers deploy these strategies, patient loyalty, caregiver engagement, and healthcare outcomes will all improve. Caring for patients will become more of what it should be: a fulfilling and enriching pursuit, not just for patients but for everyone.

56 Seconds

When I managed other nurses, some younger team members would remark that making a connection with patients was important but that they simply didn’t have time. With so much else to do, they couldn’t afford to spend 10 or 15 minutes chatting with a patient. If they did, their other work wouldn’t get done.

Sound familiar? Well, maybe there’s a way to handle this very legitimate concern.

When I became Press Ganey’s CNO, I began speaking about patient and caregiver experience before groups of nurses, administrators, and board members. I got the idea of including a bit of audience role-play. I would ask a volunteer from the audience—a total stranger—to sit or stand near me for a brief conversation. I would ask another audience member to time our interaction. Sitting down with the volunteer, I would say, “Hi, Ms. Atkinson, I’m Christy, and I’m going to be your nurse today. What would you like me to call you?”

“Call me Sandy,” she might have said.

“Sandy? Great. Sandy, is this a good time for you?”

She might have nodded her head.

“Great,” I would say. “You know, we talked in bedside shift report this morning about the procedure you’ll have this afternoon and the changes in your medication. But I’ve never taken care of you before. So, when you’re not here, what do you like to do?”

Sandy, or any other audience member I called up, might have talked about her family, her job, her hobbies, her pets, and so on. No matter how she responded, I would always be able to find a way to connect with her. If she were to tell me she had three kids, I could ask how old they were, whether they were boys or girls, where they went to school, or what sports they played. At some point, I would decide to wrap up the conversation because I controlled it. When I was ready to wrap it up, I would say something like, “I hope I can meet your kids when they come to visit. I’ll look for them and make sure they get to the right room. In the meantime, I need to do an assessment. I’m going to ask you lots of questions, and you ask me any questions that come to mind, OK? We’re in this together!”

I have performed this exercise thousands of times in many kinds of venues. Guess what? These interactions have never taken longer than two minutes! In fact, they take an average of 56 seconds.

Consider how powerful even a conversation this short can be. From now on, every time you walk into Sandy’s room to hang another IV, administer medications, change her dressing, or get her to the bathroom, you can exchange a few words about her children, what they like to do, and how proud she is of them. You and Sandy will have a lot to talk about, and none of it will have anything to do with the reason for her hospital visit. That’s the point! Sandy will now know that you know her not as the mastectomy in 902, but as a person—as Sandy who has three children who all play sports, and the baby is a girl who loves to dance. As a result of that personal connection, Sandy will feel safer, knowing that you’re looking out for her. And to enhance that feeling, you can introduce Sandy to her other caregivers so that she feels safe with them, too. Because Sandy feels safe, she’ll be more likely to reveal information that might affect her care. She’ll be more likely to comply with her care plan and to participate actively in her care—because she trusts her caregivers. A mere 56 seconds will have completely changed her experience. Fifty-six seconds!

If you’re a caregiver, or if you’re managing a team of caregivers, you’ll want to go back and practice this 56-second-long conversation. Just start doing it with colleagues, and eventually you will do it with patients. You might fear that these conversations will take longer than two minutes—that you’ll be trapped in a room with a patient who won’t stop talking. This might happen at first, but with a bit of practice, you’ll become more adept at controlling the conversation.

I recommend that managers and caregivers set aside time at least once every quarter to practice the “56 seconds” exercise. You can’t just perform this exercise a single time and assume you’ve nailed it. Have caregivers pair up with one another, with one playing the role of the patient and the other of the caregiver. To make the role-playing more realistic, have the “patient” drink a liter or two of water first, leave the call light on the floor, leave the door open, and have the “caregiver” leave the room. The “patient” will have to go to the bathroom, but he or she will lack a way of getting anyone’s attention. When the “caregiver” comes in, have another team member film the interaction (you can do this on a smartphone, no need for expensive video equipment). As I find, team members who see themselves on film in a role-play scenario often experience epiphanies about themselves and their behavior. Managers and coworkers can also use these videos to provide coaching and feedback, asking questions like, “When you saw the patient’s facial expression just then, what do you think she was feeling?” or “Is there something you could have said or done that would have made the patient feel safer and more at ease?” Have team members switch roles, and repeat the role-play exercise until every team member has had a chance to play both the patient and the caregiver. If you perform this exercise regularly, you’ll find that you and your colleagues will improve your ability to convey empathy, thus improving patient experience.

Now, you might object that not every patient is as amenable to a friendly conversation as Sandy was. What about all those patients who are belligerent or angry? In this situation, you have to take some steps to calm or soothe the patient. One young nurse I know, Julie, had a patient with congestive heart failure who had made frequent trips to the hospital. She went into this patient’s room and very cheerily said, “Hi, Frank! How’s it going today?” The patient became visibly upset, ordering the nurse out of the room and bellowing for her to “get the head nurse in here now!” Julie was confused and very upset. She had no idea what she’d done wrong. She had gone in and tried to connect with her patient, but clearly she had failed miserably.

The nurse manager asked her to tell her what happened. Julie recounted the story and her bewilderment at the patient’s response. The nurse manager then went into the patient’s room and sat down. “Mr. Patterson,” she said, “I understand that you had a problem with Julie this morning. She asked me to come to see you. Could you tell me what happened?”

“That little chippie came in here and called me Frank!” the patient responded. “She doesn’t know me, and she didn’t ask permission or bother to inquire what I wanted to be called. I am ‘the Judge.’ Everyone calls me that. I worked hard for that title. Why, even my wife calls me Judge!”

The nurse manager apologized for the misunderstanding and said that Julie would be happy to call him “the Judge” going forward. She assured the Judge that Julie was a very good nurse and would take great care of him. She asked the Judge to allow Julie to demonstrate her skills and to call if there were any further issues. The Judge replied that he would. He thanked the nurse manager for listening and addressing the issue.

Julie went in and apologized for addressing the Judge informally. She told him she was very happy to care for him, and then she asked him, “Would you tell me how you got the title the Judge?” The patient explained that he had been a judge in juvenile court for 25 years. He was proud of it—his career and his title were a big part of his identity.

Julie understood what was happening here. Her patient had lost control over his life, was frightened, and felt at the mercy of his caregivers. Recognition of his identity was now exceptionally important to him.

In some cases, we can forestall anger by asking a couple of easy questions up front. How does a patient like to be addressed? Does he or she have a professional title? If the patient is elderly, does he or she hear us when we’re speaking, or do we need to speak a little louder? It doesn’t take long to ask questions like these and document them on the chart. And sometimes, having an initial 56-second conversation can prevent patients from becoming frustrated later on in their care. Their educations, jobs, families, hobbies—these are important to them, and it means more than we might think for us to ask about them. The trust we build can help us avoid misunderstandings, and the extra context can allow us to empathize more and prevent us from becoming frustrated ourselves.

In conducting these conversations, we should always remember what’s likely the real culprit behind patients’ anger: fear. Our patients are afraid of what will happen to their bodies, how long it will take, what it will do to their lives and the lives of their family, and how much it will cost. Sometimes when people feel frightened, they mask that fear with anger. As psychologist and clinician Leon Seltzer has explained, anger is “almost never a primary emotion. For underlying it … are such core hurts as feeling disregarded, unimportant, accused, guilty, untrustworthy, devalued, rejected, powerless, and unlovable. And these feelings are capable of engendering considerable emotional pain. It’s therefore understandable that so many of us might go to great lengths to find ways of distancing ourselves from them.”2 Anger serves to help us keep our sense of vulnerability in check, and it does that so effectively that we tend not to know the function that anger is serving. The good news is that we can take action to mitigate our patients’ feelings of vulnerability and hence their expressions of anger. By allowing patients to make more decisions and by helping them to feel safe, we can prevent anger from erupting.

Remember, patients might also harbor concerns that don’t bear directly on their disease or treatment. They might worry about who will watch their children while they receive treatment, who will take care of their pets during their rehab stay, or how they will tell their boss that they will be out of the office every week for chemo. Burdened with such concerns, they might well not want to talk to you and make a connection. By asking open-ended questions during those 56-second conversations, you can elicit their concerns and possibly find ways to help them address them. As we saw in Chapter 4, a patient who has a headache might be stressed out over a nasty divorce. Offering the patient Tylenol and asking questions about the symptoms don’t address the real issue, nor do they meet the patient’s needs. Delving just a bit deeper with patients might help. At the very least, it will increase your chances of forming a positive connection. By acknowledging suffering, you can ease or prevent anger.

I am hardly suggesting that we can deescalate or please every patient all the time. Still, the vast majority of the time, we can either forestall anger or calm frustrated patients. It’s tempting to think that most patients are angry and that only angry patients fill out surveys. The truth is otherwise. Most patients who complete surveys rate the organization or provider as “good” or “very good.” Far fewer than 10 percent typically rate the organization or provider as “poor” or “very poor.”3 Let’s find ways to help all patients, including those 10 percent.

Offer Choices

As caregivers, we can and should offer patients as many choices as possible to help minimize the sense they might have of losing control. We might ask patients: “Would you prefer to take your bath in the morning or in the evening?” or “Would you like ice in your water or no ice?” These choices don’t materially impact the care we offer, nor do they place an additional time burden on us. But these questions present opportunities for patients to exert control over the seemingly uncontrollable experience of being a patient.

You might think that the ability to make decisions big and small doesn’t matter much to patients, but that’s not what the research says. In one study, researchers asked 274 patients to identify which changes they would most like to see implemented in their relationship with their physicians. The top answer: more information, autonomy, and shared decision making.4 Significantly, patients don’t just want caregivers to provide them with options. They want information about their care, which in turn allows them to participate more fully. Information, autonomy, and shared decision making topped “easier access to more sophisticated medical services,” “shorter queue[s] for tests,” and “continuity of care” on the list of patient desires—that’s how important they were.5

Talk with Patients About Their Pain

Physical pain is an abiding reality in healthcare.6 In recent years, responding to the epidemic of opioid addiction, the Joint Commission has changed the way that healthcare organizations should care for patients in pain. When prescribing pain medication, caregivers must identify “psychosocial risk factors that may affect self-reporting of pain; involve patients to develop their treatment plan and set realistic expectations and measurable goals; focus reassessment on how pain impairs physical function (e.g., ability to turn over in bed after surgery); monitor opioid prescribing patterns; and promote access to nonpharmacologic pain treatment modalities.”7 Let’s be clear: the existence of an opioid epidemic doesn’t mean that many patients don’t continue to suffer excruciating pain. They most certainly do. To avoid either overprescribing opioid medications or treating all patients as “drug seekers,” we must strive to understand our patients better and get at the underlying issues relating to their perception of pain. That means having more conversations about pain that will help us determine appropriate levels of medication.

As a consultant, I once followed a nurse into the room of a woman on her first postoperative day after a total knee replacement. The nurse did a great job in connecting with this woman as she went about her duties. However, when I looked at the whiteboard, I was shocked. It said “Pain Goal: 0.” A goal of zero pain on the first day after a total knee replacement? That’s impossible! You simply cannot get to zero pain after that surgery. This nurse set herself up to fail when she wrote that on the whiteboard, and worse, she set her patient up to fail. She thought she was allowing the patient to participate in her care and make decisions. But she neglected to set realistic expectations with her.

Chances are, a whole team of caregivers failed. A patient having an elective knee replacement might have received counseling about the pain she would experience at many points along the way: at the provider practice when she first sought treatment for her knee; when surgery was scheduled; at the preoperative call or appointment prior to the day of surgery; on the day of surgery when the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and perioperative nurses interviewed and spoke with her; when she arrived in her inpatient bed; and at every encounter in between.

Caregivers could have told her something like this: “Mrs. Smith, you are going to have a total knee replacement. After surgery, you are going to experience some pain, and we are going to do everything we can to help you manage that pain. We aren’t going to be able to get to zero pain. So, when you are at home and you have a headache or your knee hurts, what’s a reasonable amount of pain for you before you need something? Does your pain rank as a three out of ten? Or maybe a five out of ten? That’s what we’ll manage to, knowing that we just can’t get to zero right after surgery. But rest assured, we will do everything we can to help you manage your pain.”

With counseling such as this, Mrs. Smith would know to expect at least some pain. Instead of feeling surprised, upset, or fearful when she first experienced pain, she would know that the pain is normal and that caregivers will help her manage it. Caregivers would have made her feel safe.

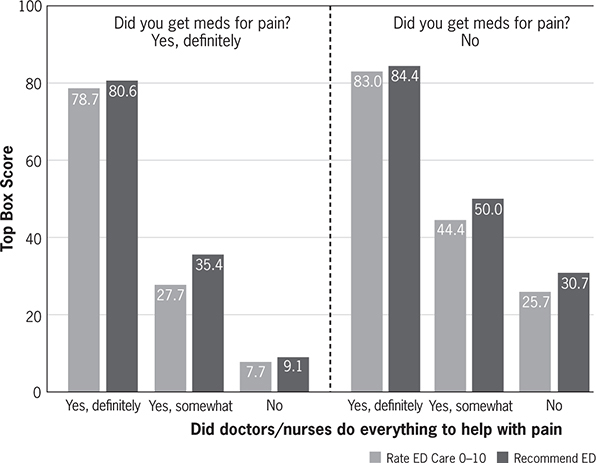

Small as they may seem, these kinds of conversations about pain make a big difference. We asked patients if they had received pain medication and if the doctors and nurses did everything they could to help them manage their pain. Some patients said yes to both questions. Others said that they had not received pain medication, but that doctors and nurses had done everything they could to help them manage pain. As Figure 5.1 shows, the group that did not receive pain medication rated the ED more highly and indicated that they would recommend the hospital more. In other words, it’s not about the drug. It’s about the connection, communication, and information.

Figure 5.1 How conversations about pain affect patients’ willingness to recommend

Round Like You Own It

I have yet to meet a nurse who is not in a patient’s room at least hourly. We’ve always done that. But is hourly rounding a good idea? The clear answer is yes. And just as important as rounding hourly is rounding purposefully. Caregivers must be in the room frequently to accomplish tasks required for patient care, whether they are in the hospital, the provider’s office, a rehab facility, or an outpatient clinic. Purposeful rounding allows staff to be proactive and anticipate patient needs. When nurses feel that they can be proactive and watch out for patients, the incidence of falls and pressure injuries declines. And our research has demonstrated that patients who experience hourly rounds during their stay evaluate their care more highly in all areas across both Press Ganey and HCAHPS survey measures. Items on the Press Ganey survey most impacted by hourly rounds are “Response to concerns and complaints made during your stay” and “Promptness in responding to the call button.” The more consistently hourly rounds occur, the more positively patients evaluate their care experiences and the more likely they are to recommend the hospital.8

If rounding is essential, how should individual caregivers best perform their rounds? Here we have no shortage of good advice. One 2006 article in the American Journal of Nursing suggested guidelines that caregivers should follow in every patient round, such as inquiring about pain, asking about toileting assistance, assessing positioning, and assuring that personal items were within reach. After the authors consistently deployed these strategies, they found that patients used their call lights less frequently and that their overall experience improved.9

To drive consistency, the authors used scripting and checklists. While these approaches help drive consistency, they also come with an unwanted side effect: they make caregiver interactions seem less genuine. When Aaron was in the rehab hospital, the staff did amazing work with patients with head and spinal cord injuries. Miracles happened there every day, thanks to their good work. And yet every time new caregivers entered the room to introduce themselves, they said exactly the same thing—not kind of the same thing, but exactly the same thing. Obviously, their communications had been scripted. While these team members delivered great care, their demeanor came across to us as somewhat less authentic than if they had simply talked to us in their own, idiosyncratic ways. Scripting is a fine tool when used over the short term to help team members begin to understand how to communicate. But it can only help after they understand the deeper purpose behind it. And we should quickly look past the script so as to sustain the authenticity that helps us to connect with others. We should script the sentiment we are trying to convey, not the words themselves.

As caregivers, we can become too checklist oriented, task driven, and, in this case, script reliant. So what can we do about it? An important strategy is to take more time practicing how to connect. Ask for help during orientation sessions, and if you’re having trouble connecting with patients, ask for follow-up coaching. Focus on specific behaviors, like how to let patients know that you’re listening to them. If certain colleagues of yours seem to excel at making connections, try to observe them, learn their “secrets,” and incorporate those secrets into your own work with patients. Small investments of time like these can reap huge returns, enhancing the experience not only of patients but of your fellow caregivers, too.

While we individual caregivers should work on improving our own rounding practices, managers should round as well. Unfortunately, many managers struggle to understand how to help their staff round better, and they also struggle to model desired behaviors. Once while touring a hospital, I asked a CNO what she had done to improve how individual caregivers perform their rounds. She recounted that they had tried many techniques and initiatives that hadn’t worked (this organization had been at the forefront of lean methodology in healthcare and had applied that thinking to rounding). Ultimately, this CNO related, the hospital’s leadership had decided that it “couldn’t really hold people accountable for rounding unless we knew that they were competent to round.” The committee developed a checklist that described components of good rounding by nursing staff. It then trained staff around the checklist, including ample discussion of purpose. Each manager then had to observe each staff member on three separate occasions to assure that the staff member was rounding correctly and to coach him or her when need be. After three “good” rounds, the staff member was “checked off” as competent. “We can now hold them accountable,” this CNO said. “We know they are competent.”

But this organization’s efforts didn’t stop there. Managers performed unannounced observational audits to assure that employees were still rounding correctly. These audits took place on an ongoing basis indefinitely. As a result of this effort, team members were now so well practiced in rounding that they “owned” it. They did it effortlessly and automatically, as part of the standard way they cared for patients. They still used a rounding tool to log the rounds, but the observational audits and coaching made the real difference, driving consistency and sustainability.

As vital as it is, accountability is not enough to make caregiver rounding successful. Individual caregivers have to own rounding. We shouldn’t just treat rounding as one more thing we have to do during our workdays. Rather, we should partake of it as a way to demonstrate the empathy, compassion, and desire to serve that prompted us to enter healthcare in the first place. Working as a caregiver isn’t just a job, but a calling. When we reduce this calling to a series of tasks, the work itself loses meaning. Whether you’re a nurse, physician, or tech rounding on patients or a leader doing so on staff, the act of rounding affords a chance to forge connections with the very people who have put their trust in us. It is simply the way we do what we do.

Practice Both Consistency and Critical Thinking

I wish I had a nickel for every time I heard, “Yeah, we tried that, but it hasn’t worked so far.” When I hear people at an organization saying this, I will often ask to walk around and observe as a “secret shopper.” I will have attended leadership meetings by then, having heard all the right things. I will also see purposeful rounding logs in rooms that, amazingly, show that rounds are happening exactly at the same time in every room. Imagine that!

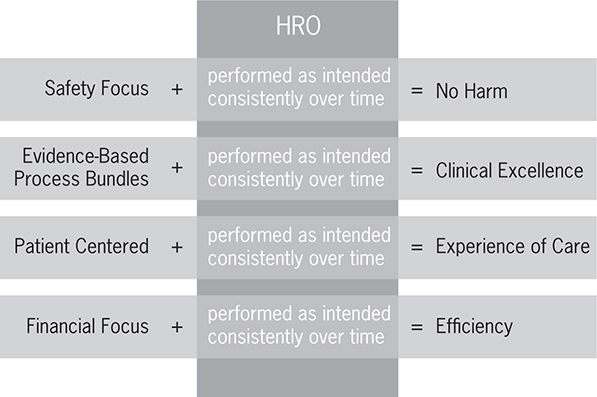

Of course, rounding isn’t happening uniformly at these hospitals. And that points to a broader issue. We talk about the patient experience and patient safety, but all too often we flounder by failing to practice the required behaviors consistently. As Figure 5.2 demonstrates, we don’t achieve reliability by focus, evidence, patient centeredness, or financial motivation alone. These are all important, but it’s consistent focus over time that leads to highly reliable, zero-harm clinical excellence, patient experience, and efficiency—all of which, in turn, lead to better reimbursement.

Figure 5.2 The importance of consistent performance over time

Consistency is so important, of course, because it helps us reduce variability, which often lurks as the enemy of quality. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, when clinical pathways began to gain popularity, several physicians said to me, “Don’t tell me how to take care of my patients! This is cookbook medicine!” Clinical pathways were developed to standardize care for high-risk and problem-prone conditions. As research has documented, total joint replacement patients who followed a clinical pathway that standardized and organized care experienced reduced lengths of stay and fewer postoperative complications like deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, and infections.10 Consistency drove quality improvement. So my response to those physicians was usually, “You’re right! It is cookbook medicine. Why do you use a cookbook? To get the best result every time!” Consistency is important in everything we do as caregivers, from the way we care clinically for patients to the way we round and interact with our patients and colleagues.

By emphasizing consistency so strongly, I am by no means suggesting that caregivers should think and behave like robots. Absolutely not! To consistency, they must add another vital competency: critical thinking.

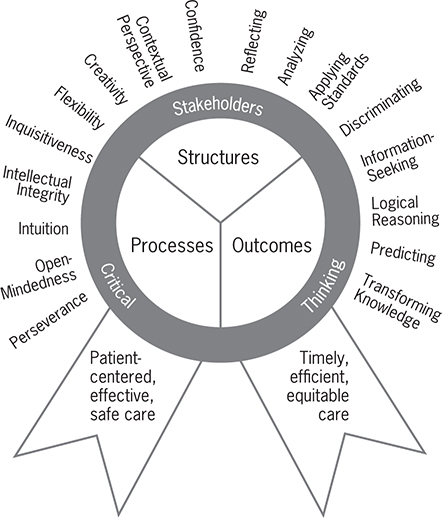

As caregivers, we talk a lot about critical thinking. It’s part of virtually every curriculum in healthcare education. In a 2013 brief, the Council for Aid to Education observed that “while there are many desirable outcomes of college education, there is widespread agreement that critical thinking skills are among the most important.” In particular, the council noted, critical thinking skills “are seen as essential for accessing and analyzing the information needed to address the complex, non-routine challenges facing workers in the 21st century.”11 Likewise, in their book, Critical Thinking Tactics for Nurses, M. Gaie Rubenfeld and Barbara Scheffer describe their efforts to identify a common definition for critical thinking in nursing. They arrived at 17 dimensions: 10 “habits of mind” (“confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance, and reflection”) and seven cognitive skills (“analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, [and] transforming knowledge”).12 Considering each of these elements, we can readily understand how they help caregivers achieve the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim of better experience of care, healthy populations, and lower cost. We can also see how they help us achieve the IOM (Institute of Medicine) charge of achieving the following five competencies:13

• Provide patient-centered care—identify, respect, and care about patients’ differences, values, preferences, and expressed needs; relieve pain and suffering; coordinate continuous care; listen to, clearly inform, communicate with, and educate patients; share decision making and management; and continuously advocate disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles, including a focus on population health.

• Work in interdisciplinary teams—cooperate, collaborate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable.

• Employ evidence-based practice—integrate best research with clinical expertise and patient values for optimum care, and participate in learning and research activities to the extent feasible.

• Apply quality improvement—identify errors and hazards in care; understand and implement basic safety design principles, such as standardization and simplification; continually understand and measure quality of care in terms of structure, process, and outcomes in relation to patient and community needs; design and test interventions to change processes and systems of care, with the objective of improving quality.

• Utilize informatics—communicate, manage knowledge, mitigate error, and support decision making using information technology.

Clearly, it’s critical for caregivers to think critically. And yet for all the talk, we in healthcare don’t employ critical thinking enough. As individual caregivers, we must dedicate ourselves to it, tempering our decision making by constantly questioning, searching for evidence, analyzing data, and synthesizing data. We must challenge ourselves to avoid behaving in certain ways simply because “that’s the way we’ve always done it.” To drive the patient experience and safety in healthcare, we must sustain situational awareness, attention to detail, 360-degree communication, clarification of information, appropriate use of protocol, and reasoned decision making. We must validate information, asking ourselves if a given contention makes sense and verifying what we think we know with evidence from independent, qualified sources. When peers think critically and watch out for one another, providing situational awareness and immediate feedback, the number of errors decreases.

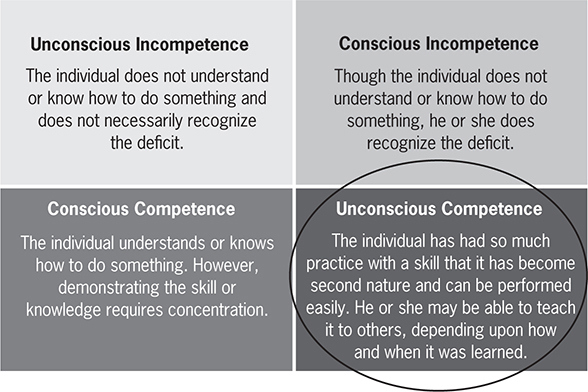

At the extreme, as we become increasingly proficient at critical thinking, seeking feedback and becoming more self-aware, we can achieve what Maslow, in his Four Stages of Learning theory, called “unconscious competence” (see Figure 5.3). Maslow conceived of four stages that span a continuum, starting with unconscious incompetence (an inability to perform a task well, coupled with a lack of awareness of the deficit) and going all the way up to unconscious competence (an individual’s ability, grounded in intensive practice, to perform a task not only well, but effortlessly and unconsciously).14

Figure 5.3 Maslow’s Four Stages of Learning

In the case of nursing, caregivers who achieve unconscious competence have not only applied their critical faculties to improve. They’ve mastered skills to such an extent that, as Patricia Benner and her colleagues noted, they “do not rely on rules and logical thought processes in problem-solving and decisionmaking. Instead, they use abstract principles, can see the situation as a complex whole, perceive situations comprehensively, and can be fully involved in the situation.”15 These nurses and other caregivers “can perform high-level care without conscious awareness of the knowledge they are using, and they are able to provide that care with flexibility and speed.”16 Ultimately, then, caregivers require critical thinking to excel, and they arrive at such a state of mastery that the task becomes second nature, and consistency ensues.

All of us, not only nurses, must adopt critical thinking skills in order to provide the best care possible to the patients we serve. In Chapter 7, when we discuss how organizations become more compassionate and connected, we’ll delve into critical thinking from a systemic perspective, not merely an individual perspective. In their book Critical Thinking Tactics for Nurses, Rubenfeld and Scheffer represented this thinking for both organizations and individuals as a medallion representing the IOM competency of applying quality improvement (see Figure 5.4).17 Using Donabedian’s triad of structure, processes, and outcomes, Figure 5.4 captures the behaviors, attitudes, and abilities we in healthcare require to achieve quality of care and continuous improvement, both as individuals and as interdisciplinary teams.

Figure 5.4 Medallion of safe, quality healthcare through critical thinking

Cultivate Your Resilience

Although few caregivers would dispute that the behaviors described in this book would reduce the suffering of patients and colleagues, we often see a disconnect between what we caregivers want to do and what our “compassion tank”—our internal storehouse of compassion—allows. That’s where the quality of resilience comes in. We can define resilience as “that ineffable quality that allows some people to be knocked down by life and come back stronger than ever. Rather than letting failure overcome them and drain their resolve, they find a way to rise from the ashes.”18 In effect, resilience is a shield that allows us to repel some of the inherent and avoidable suffering prevalent in healthcare today. It is both the opposite of and the antidote to burnout, allowing us to withstand suffering in all its guises and to deliver Compassionate Connected Care to our patients.

So what fuels resilience? The rewards and benefits attached to healthcare do. If the pain for caregivers exceeds the reward or benefit, we become disengaged and burned out. But if we perceive the reward as greater than the pain, we bounce back and continue to reengage. Significantly, that reward need not be monetary or even tangible. Intangible rewards like recognition, praise, and intrinsic motivation often suffice to keep us on track and engaged on the job.

Individual caregivers also can take steps to build up their resilience. For instance, we can embrace a mindfulness practice. In today’s fast-paced world, it’s hard to be mindful. Smartphones by our side, we are constantly bombarded by stimuli, both at work and at home. I once asked my daughter, a teacher, why educators paid so much attention to bullying these days. Hasn’t it always been a problem? “Mom,” she told me, “it used to be that kids would be bullied at school, but then they could come home and be safe and get away from the bullying. But now, with cell phones, Facebook, and other social media, kids cannot ever get away from it. It’s always there and they can’t turn it off. There is no safe place anymore.” That’s true for all of us.

To become more mindful, try turning off your phone for a few minutes. Allow yourself to be in the moment. If you’re eating, sense what’s on your tongue. If you’re touching something, sense the feeling on your fingers. If you’re sitting comfortably, sense what every part of your body feels like. As simple as these practices are, they’re also immensely powerful. According to psychologists Daphne Davis and Jeffrey Hayes, “Mindfulness meditation promotes metacognitive awareness, decreases rumination via disengagement from perseverative cognitive activities and enhances attentional capacities through gains in working memory. These cognitive gains, in turn, contribute to effective emotion-regulation strategies.”19 Davis and Hayes go on to enumerate further benefits, like stress alleviation, working memory enhancement, increased focus, reduced emotional reactivity, increased cognitive flexibility, more relationship satisfaction, greater self-insight, a more acute moral sense, greater intuition, a better ability to control fear, increased immune functioning, and improvement in well-being.20 Most remarkable, perhaps, research has shown that mindfulness and positive thinking actually had a beneficial effect on the DNA of breast cancer patients (i.e., the lengthening of telomeres), suggesting that the effects of mindfulness meditation on the body may be far more extensive than we had ever imagined.21 In all these ways, consistently practicing mindfulness reinforces your resilience shield, fueling your “compassion tank” so that you can deliver more Compassionate Connected Care.

Not only must caregivers practice mindfulness; to become more resilient, they must also avoid certain missteps, like personalizing negative situations that are not their fault, or assuming that an obstacle in one area will apply to all areas, or believing that a particular emotion (for instance, joy or sadness) will last forever.22 Caregivers can also enhance resilience by adopting a gratitude practice. Try taking five minutes each day to write down three things that went well. Or try writing a letter of appreciation to someone explaining something the person did, how it made you feel, and the benefits you received.23 Or try taking a few minutes to admire and feel inspired by a beautiful sunset. Or try writing about challenges or negative experiences and the positive benefits gleaned from them. When people think about good things that come out of bad experiences, they report less distress, fewer disruptive thoughts, less negativity, and more meaning in their lives.24

You must also remember to care for your body and mind. Being physically and mentally fit isn’t just about looking great. It’s about feeling great and having enough energy for yourself and the people for whom you care. You can’t give of yourself to others unless and until you give of yourself to you first. The American Nurses Association “defines a healthy nurse as one who actively focuses on creating and maintaining a balance and synergy of physical, intellectual, emotional, social, spiritual, personal and professional wellbeing. A healthy nurse lives life to the fullest capacity, across the wellness/illness continuum, as they become stronger role models, advocates, and educators, personally, for their families, their communities and work environments, and ultimately for their patients.”25 It’s a lofty ideal, and one to which we all should strive—for ourselves and for the sake of reducing or preventing suffering in our patients.

Does all of this sound “fluffy” to you? It did to me, until I began to practice mindfulness during my breast cancer treatment and then later with Aaron’s shooting and rehabilitation. It was amazing what just 10 minutes a day of being mindful and reducing the clutter and noise in my head could do. I was able to think more clearly, accomplish more in my work, and be more present for my family, colleagues, and clients.

In one class on mindfulness I attended, the leader gave us raisins and had us just look at them, noticing the color and the shape. Then we spent time smelling the raisins. Then we were asked to really feel the raisins, their grooves and squishiness. Then he had us put our raisins on our tongues and notice how they felt in our mouths. Then he had us savor their sweetness and the sensation of biting into them. While each of us was eating our raisins, we couldn’t think about anything else because our minds and our senses were totally devoted to this extended act. I found this exercise astounding—and I don’t even like raisins. As one study has shown, mindful eaters experience “lower body weights, a greater sense of well-being, and fewer symptoms of eating disorders.”26

After the raisin class, I attended a mindful writing class. During this session, the leader asked a simple question, something like, “Tell me about your best day.” The participants were asked to start writing on a blank sheet of paper. We were told to be specific and to really think about what made that day great. How did it feel physically, emotionally, and spiritually? Then we shared what we wrote. Several of my classmates cried while recounting why they had chosen to write about a particular day. The experience was profound.

I challenge you to try the resilience-building exercises I’ve described, whether it’s a gratitude practice, mindful eating, or something else. As with other strategies discussed in this book, you can’t just “do resilience” once and check it off your list. You must practice it daily so that it becomes something that you habitually do and thus becomes a part of you. Make yourself unconsciously competent.

The Impact of a Compassionate Connected Caregiver

Some caregivers might have an easier time taking tangible steps to make Compassionate Connected Care a reality. Over the course of their careers, they might have seen the impact of the behaviors I’ve described on patients and families and felt inspired to integrate these behaviors into their everyday practice. Or as patients themselves, they might have experienced firsthand the wonderful difference that caregivers make when they deliver care compassionately and in a connected way.

My colleague Julie, a nurse for 35 years, recently found herself in pain so horrific that it sent her to the emergency room for the first time as a patient. Julie quickly underwent lab and imaging tests. Her husband had overheard imaging personnel talking with the surgeon on call, Dr. Lee Zho. “I don’t know what you’re going to do with this one!” they said. “Good luck.” As you can imagine, Julie and her husband were terrified.

Julie met Dr. Zho for the first time in the emergency room after her tests were completed. After introducing himself, he immediately put Julie at ease. He leaned in, looked her in the eye, took her hand, and said: “I’m so glad you came in when you did.” As Julie remembers it, the expression on his face conveyed deep concern but also comfort. In just a few short seconds, he let her know that he truly cared about her as a person and a patient.

Dr. Zho proceeded to inform Julie of his plan to perform immediate, emergency surgery resulting in an ostomy. Because of her nursing experience, Julie knew full well what an ostomy was. She had cared for many a patient with one, and yet she still reacted with shock and disbelief. Dr. Zho paused to watch for Julie’s reaction and understanding of what he’d just stated. As Julie recounts, she found his gentle tone of voice and the look of genuine caring in his eyes deeply reassuring. “I’ll never forget that interaction,” Julie says. “It made me feel completely safe, cared about, informed, and as prepared as I could be. I felt at ease for the first time in over a week.”

Julie was fortunate to have other caregivers who lived the Compassionate Connected Care model. Her nurse Lisa was fully present at every interaction, reading every nonverbal cue Julie threw her way in order not to miss an unstated need or concern. And as Julie later learned, Lisa remained focused even though she had two small children and a terminally ill husband. Lisa maintained appropriate professional boundaries, and yet she and Julie connected. “Watching Lisa,” Julie says, “I learned a lot about how to be mindful in the moment, even in the face of major life and work distractions. And I also learned about how much a caring, healing environment affects both patients and the caregiver’s own health and resilience.” Tears come to Julie’s eyes as she tells me that she will forever feel grateful for Lisa’s care and that Lisa’s family will always be in her prayers.

What a life-changing connection in a matter of days! Imagine the connections that you could make with your patients and colleagues, each and every day, as you put the Compassionate Connected Care model to work.