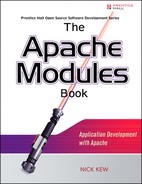

14.9. Cache-Control

The Cache-Control general-header field is used to specify directives that MUST be obeyed by all caching mechanisms along the request/response chain. The directives specify behavior intended to prevent caches from adversely interfering with the request or response. These directives typically override the default caching algorithms. Cache directives are unidirectional in that the presence of a directive in a request does not imply that the same directive is to be given in the response.

Note that HTTP/1.0 caches might not implement Cache-Control and might only implement Pragma: no-cache (see section 14.32).

Cache directives MUST be passed through by a proxy or gateway application, regardless of their significance to that application, since the directives might be applicable to all recipients along the request/response chain. It is not possible to specify a cache-directive for a specific cache.

When a directive appears without any 1#field-name parameter, the directive applies to the entire request or response. When such a directive appears with a 1#field-name parameter, it applies only to the named field or fields, and not to the rest of the request or response. This mechanism supports extensibility; implementations of future versions of the HTTP protocol might apply these directives to header fields not defined in HTTP/1.1.

The cache-control directives can be broken down into these general categories:

- Restrictions on what are cacheable; these may only be imposed by the origin server.

- Restrictions on what may be stored by a cache; these may be imposed by either the origin server or the user agent.

- Modifications of the basic expiration mechanism; these may be imposed by either the origin server or the user agent.

- Controls over cache revalidation and reload; these may only be imposed by a user agent.

- Control over transformation of entities.

- Extensions to the caching system.

14.9.1. What Is Cacheable

By default, a response is cacheable if the requirements of the request method, request header fields, and the response status indicate that it is cacheable. Section 13.4 summarizes these defaults for cacheability. The following Cache-Control response directives allow an origin server to override the default cacheability of a response.

public

Indicates that the response MAY be cached by any cache, even if it would normally be non-cacheable or cacheable only within a non-shared cache. (See also Authorization, section 14.8, for additional details.)

private

Indicates that all or part of the response message is intended for a single user and MUST NOT be cached by a shared cache. This allows an origin server to state that the specified parts of the response are intended for only one user and are not a valid response for requests by other users. A private (non-shared) cache MAY cache the response.

Note: This usage of the word “private” only controls where the response may be cached, and cannot ensure the privacy of the message content.

no-cache

If the no-cache directive does not specify a field-name, then a cache MUST NOT use the response to satisfy a subsequent request without successful revalidation with the origin server. This allows an origin server to prevent caching even by caches that have been configured to return stale responses to client requests.

If the no-cache directive does specify one or more field-names, then a cache MAY use the response to satisfy a subsequent request, subject to any other restrictions on caching. However, the specified field-name(s) MUST NOT be sent in the response to a subsequent request without successful revalidation with the origin server. This allows an origin server to prevent the reuse of certain header fields in a response, while still allowing caching of the rest of the response.

Note: Most HTTP/1.0 caches will not recognize or obey this directive.

14.9.2. What May Be Stored by Caches

no-store

The purpose of the no-store directive is to prevent the inadvertent release or retention of sensitive information (for example, on backup tapes). The no-store directive applies to the entire message and MAY be sent either in a response or in a request. If sent in a request, a cache MUST NOT store any part of either this request or any response to it. If sent in a response, a cache MUST NOT store any part of either this response or the request that elicited it. This directive applies to both non-shared and shared caches. “MUST NOT store” in this context means that the cache MUST NOT intentionally store the information in nonvolatile storage, and MUST make a best-effort attempt to remove the information from volatile storage as promptly as possible after forwarding it.

Even when this directive is associated with a response, users might explicitly store such a response outside of the caching system (e.g., with a “Save As” dialog). History buffers MAY store such responses as part of their normal operation.

The purpose of this directive is to meet the stated requirements of certain users and service authors who are concerned about accidental releases of information via unanticipated accesses to cache data structures. While the use of this directive might improve privacy in some cases, we caution that it is NOT in any way a reliable or sufficient mechanism for ensuring privacy. In particular, malicious or compromised caches might not recognize or obey this directive, and communications networks might be vulnerable to eavesdropping.

14.9.3. Modifications of the Basic Expiration Mechanism

The expiration time of an entity MAY be specified by the origin server using the Expires header (see section 14.21). Alternatively, it MAY be specified using the maxage directive in a response. When the max-age cache-control directive is present in a cached response, the response is stale if its current age is greater than the age value given (in seconds) at the time of a new request for that resource. The max-age directive on a response implies that the response is cacheable (i.e., “public”) unless some other, more restrictive cache directive is also present.

If a response includes both an Expires header and a max-age directive, the max-age directive overrides the Expires header, even if the Expires header is more restrictive. This rule allows an origin server to provide, for a given response, a longer expiration time to an HTTP/1.1 (or later) cache than to an HTTP/1.0 cache. This might be useful if certain HTTP/1.0 caches improperly calculate ages or expiration times, perhaps due to desynchronized clocks.

Many HTTP/1.0 cache implementations will treat an Expires value that is less than or equal to the response Date value as being equivalent to the Cache-Control response directive “no-cache.” If an HTTP/1.1 cache receives such a response, and the response does not include a Cache-Control header field, it SHOULD consider the response to be non-cacheable in order to retain compatibility with HTTP/1.0 servers.

Note: An origin server might wish to use a relatively new HTTP cache control feature, such as the “private” directive, on a network including older caches that do not understand that feature. The origin server will need to combine the new feature with an Expires field whose value is less than or equal to the Date value. This will prevent older caches from improperly caching the response.

s-maxage

If a response includes an s-maxage directive, then for a shared cache (but not for a private cache), the maximum age specified by this directive overrides the maximum age specified by either the max-age directive or the Expires header. The s-maxage directive also implies the semantics of the proxy-revalidate directive (see section 14.9.4)—i.e., that the shared cache must not use the entry after it becomes stale to respond to a subsequent request without first revalidating it with the origin server. The s-maxage directive is always ignored by a private cache.

Note that most older caches, not compliant with this specification, do not implement any cache-control directives. An origin server wishing to use a cache-control directive that restricts, but does not prevent, caching by an HTTP/1.1-compliant cache MAY exploit the requirement that the max-age directive overrides the Expires header, and the fact that pre-HTTP/1.1-compliant caches do not observe the maxage directive.

Other directives allow a user agent to modify the basic expiration mechanism. These directives MAY be specified on a request:

max-age

Indicates that the client is willing to accept a response whose age is no greater than the specified time in seconds. Unless the max-stale directive is also included, the client is not willing to accept a stale response.

min-fresh

Indicates that the client is willing to accept a response whose freshness lifetime is no less than its current age plus the specified time in seconds. That is, the client wants a response that will still be fresh for at least the specified number of seconds.

max-stale

Indicates that the client is willing to accept a response that has exceeded its expiration time. If max-stale is assigned a value, then the client is willing to accept a response that has exceeded its expiration time by no more than the specified number of seconds. If no value is assigned to max-stale, then the client is willing to accept a stale response of any age.

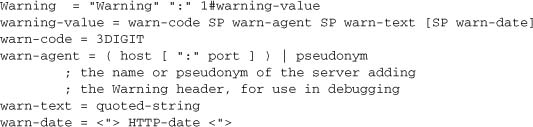

If a cache returns a stale response, either because of a max-stale directive on a request, or because the cache is configured to override the expiration time of a response, the cache MUST attach a Warning header to the stale response, using Warning 110 (Response is stale).

A cache MAY be configured to return stale responses without validation, but only if this does not conflict with any “MUST”-level requirements concerning cache validation (e.g., a “must-revalidate” cache-control directive).

If both the new request and the cached entry include “max-age” directives, then the lesser of the two values is used for determining the freshness of the cached entry for that request.

14.9.4. Cache Revalidation and Reload Controls

Sometimes a user agent might want or need to insist that a cache revalidate its cache entry with the origin server (and not just with the next cache along the path to the origin server), or to reload its cache entry from the origin server. End-to-end revalidation might be necessary if either the cache or the origin server has overestimated the expiration time of the cached response. End-to-end reload may be necessary if the cache entry has become corrupted for some reason.

End-to-end revalidation may be requested either when the client does not have its own local cached copy, in which case we call it “unspecified end-to-end revalidation,” or when the client does have a local cached copy, in which case we call it “specific end-to-end revalidation.”

The client can specify these three kinds of action using Cache-Control request directives:

End-to-end reload

The request includes a “no-cache” cache-control directive or, for compatibility with HTTP/1.0 clients, “Pragma: no-cache.” Field names MUST NOT be included with the no-cache directive in a request. The server MUST NOT use a cached copy when responding to such a request.

Specific end-to-end revalidation

The request includes a “max-age=0” cache-control directive, which forces each cache along the path to the origin server to revalidate its own entry, if any, with the next cache or server. The initial request includes a cache-validating conditional with the client’s current validator.

Unspecified end-to-end revalidation

The request includes a “max-age=0” cache-control directive, which forces each cache along the path to the origin server to revalidate its own entry, if any, with the next cache or server. The initial request does not include a cache-validating conditional; the first cache along the path (if any) that holds a cache entry for this resource includes a cache-validating conditional with its current validator.

max-age

When an intermediate cache is forced, by means of a max-age=0 directive, to revalidate its own cache entry, and the client has supplied its own validator in the request, the supplied validator might differ from the validator currently stored with the cache entry. In this case, the cache MAY use either validator in making its own request without affecting semantic transparency.

However, the choice of validator might affect performance. The best approach is for the intermediate cache to use its own validator when making its request. If the server replies with 304 (Not Modified), then the cache can return its now validated copy to the client with a 200 (OK) response. If the server replies with a new entity and cache validator, however, the intermediate cache can compare the returned validator with the one provided in the client’s request, using the strong comparison function. If the client’s validator is equal to the origin server’s, then the intermediate cache simply returns 304 (Not Modified). Otherwise, it returns the new entity with a 200 (OK) response.

If a request includes the no-cache directive, it SHOULD NOT include min-fresh, max-stale, or max-age.

only-if-cached

In some cases, such as times of extremely poor network connectivity, a client may want a cache to return only those responses that it currently has stored, and not to reload or revalidate with the origin server. To do this, the client may include the only-if-cached directive in a request. If it receives this directive, a cache SHOULD either respond using a cached entry that is consistent with the other constraints of the request, or respond with a 504 (Gateway Timeout) status. However, if a group of caches is being operated as a unified system with good internal connectivity, such a request MAY be forwarded within that group of caches.

must-revalidate

Because a cache MAY be configured to ignore a server’s specified expiration time, and because a client request MAY include a max-stale directive (which has a similar effect), the protocol also includes a mechanism for the origin server to require revalidation of a cache entry on any subsequent use. When the must-revalidate directive is present in a response received by a cache, that cache MUST NOT use the entry after it becomes stale to respond to a subsequent request without first revalidating it with the origin server (i.e., the cache MUST do an end-to-end revalidation every time, if, based solely on the origin server’s Expires or max-age value, the cached response is stale).

The must-revalidate directive is necessary to support reliable operation for certain protocol features. In all circumstances, an HTTP/1.1 cache MUST obey the must-revalidate directive; in particular, if the cache cannot reach the origin server for any reason, it MUST generate a 504 (Gateway Timeout) response.

Servers SHOULD send the must-revalidate directive if and only if failure to revalidate a request on the entity could result in incorrect operation, such as a silently unexecuted financial transaction. Recipients MUST NOT take any automated action that violates this directive, and MUST NOT automatically provide an unvalidated copy of the entity if revalidation fails.

Although this is not recommended, user agents operating under severe connectivity constraints MAY violate this directive but, if so, MUST explicitly warn the user that an unvalidated response has been provided. The warning MUST be provided on each unvalidated access, and SHOULD require explicit user confirmation.

proxy-revalidate

The proxy-revalidate directive has the same meaning as the must-revalidate directive, except that it does not apply to non-shared user agent caches. It can be used on a response to an authenticated request to permit the user’s cache to store and later return the response without needing to revalidate it (since it has already been authenticated once by that user), while still requiring proxies that service many users to revalidate each time (in order to make sure that each user has been authenticated). Note that such authenticated responses also need the public cache control directive in order to allow them to be cached at all.

14.9.5. No-Transform Directive

no-transform

Implementers of intermediate caches (proxies) have found it useful to convert the media type of certain entity bodies. A non-transparent proxy might, for example, convert between image formats in order to save cache space or to reduce the amount of traffic on a slow link.

Serious operational problems occur, however, when these transformations are applied to entity bodies intended for certain kinds of applications. For example, applications for medical imaging, scientific data analysis, and those using end-to-end authentication all depend on receiving an entity body that is bit-for-bit identical to the original entity-body.

Therefore, if a message includes the no-transform directive, an intermediate cache or proxy MUST NOT change those headers that are listed in section 13.5.2 as being subject to the no-transform directive. This implies that the cache or proxy MUST NOT change any aspect of the entity-body that is specified by these headers, including the value of the entity-body itself.

14.9.6. Cache Control Extensions

The Cache-Control header field can be extended through the use of one or more cache-extension tokens, each with an optional assigned value. Informational extensions (those which do not require a change in cache behavior) MAY be added without changing the semantics of other directives. Behavioral extensions are designed to work by acting as modifiers to the existing base of cache directives. Both the new directive and the standard directive are supplied, such that applications which do not understand the new directive will default to the behavior specified by the standard directive, and those that understand the new directive will recognize it as modifying the requirements associated with the standard directive. In this way, extensions to the cache-control directives can be made without requiring changes to the base protocol.

This extension mechanism depends on an HTTP cache obeying all of the cache-control directives defined for its native HTTP-version, obeying certain extensions, and ignoring all directives that it does not understand.

For example, consider a hypothetical new response directive called community which acts as a modifier to the private directive. We define this new directive to mean that, in addition to any non-shared cache, any cache which is shared only by members of the community named within its value may cache the response. An origin server wishing to allow the UCI community to use an otherwise private response in their shared cache(s) could do so by including

Cache-Control: private, community="UCI"

A cache seeing this header field will act correctly even if the cache does not understand the community cache-extension, since it will also see and understand the private directive and thus default to the safe behavior.

Unrecognized cache-directives MUST be ignored; it is assumed that any cache-directive likely to be unrecognized by an HTTP/1.1 cache will be combined with standard directives (or the response’s default cacheability) such that the cache behavior will remain minimally correct even if the cache does not understand the extension(s).

14.10. Connection

The Connection general-header field allows the sender to specify options that are desired for that particular connection and MUST NOT be communicated by proxies over further connections.

The Connection header has the following grammar:

![]()

HTTP/1.1 proxies MUST parse the Connection header field before a message is forwarded and, for each connection-token in this field, remove any header field(s) from the message with the same name as the connection-token. Connection options are signaled by the presence of a connection-token in the Connection header field, not by any corresponding additional header field(s), since the additional header field may not be sent if there are no parameters associated with that connection option.

Message headers listed in the Connection header MUST NOT include end-to-end headers, such as Cache-Control.

HTTP/1.1 defines the “close” connection option for the sender to signal that the connection will be closed after completion of the response. For example,

Connection: close

in either the request or the response header fields indicates that the connection SHOULD NOT be considered “persistent” (section 8.1) after the current request/response is complete.

HTTP/1.1 applications that do not support persistent connections MUST include the “close” connection option in every message.

A system receiving an HTTP/1.0 (or lower-version) message that includes a Connection header MUST, for each connection-token in this field, remove and ignore any header field(s) from the message with the same name as the connection-token. This protects against mistaken forwarding of such header fields by pre-HTTP/1.1 proxies. See section 19.6.2.

14.11. Content-Encoding

The Content-Encoding entity-header field is used as a modifier to the media-type. When present, its value indicates what additional content-codings have been applied to the entity-body, and thus what decoding mechanisms must be applied in order to obtain the media-type referenced by the Content-Type header field. Content-Encoding is primarily used to allow a document to be compressed without losing the identity of its underlying media type.

Content-Encoding = "Content-Encoding" ":" 1#content-coding

Content-codings are defined in section 3.5. An example of its use is

Content-Encoding: gzip

The content-coding is a characteristic of the entity identified by the Request-URI. Typically, the entity-body is stored with this encoding and is only decoded before rendering or analogous usage. However, a non-transparent proxy MAY modify the content-coding if the new coding is known to be acceptable to the recipient, unless the “no-transform” cache-control directive is present in the message.

If the content-coding of an entity is not “identity,” then the response MUST include a Content-Encoding entity-header (section 14.11) that lists the non-identity content-coding(s) used.

If the content-coding of an entity in a request message is not acceptable to the origin server, the server SHOULD respond with a status code of 415 (Unsupported Media Type).

If multiple encodings have been applied to an entity, the content codings MUST be listed in the order in which they were applied. Additional information about the encoding parameters MAY be provided by other entity-header fields not defined by this specification.

14.12. Content-Language

The Content-Language entity-header field describes the natural language(s) of the intended audience for the enclosed entity. Note that this might not be equivalent to all the languages used within the entity-body.

Content-Language = "Content-Language" ":" 1#language-tag

Language tags are defined in section 3.10. The primary purpose of Content-Language is to allow a user to identify and differentiate entities according to the user’s own preferred language. Thus, if the body content is intended only for a Danish-literate audience, the appropriate field is

Content-Language: da

If no Content-Language is specified, the default is that the content is intended for all language audiences. This might mean that the sender does not consider it to be specific to any natural language, or that the sender does not know for which language it is intended.

Multiple languages MAY be listed for content that is intended for multiple audiences. For example, a rendition of the “Treaty of Waitangi,” presented simultaneously in the original Maori and English versions, would call for

Content-Language: mi, en

However, just because multiple languages are present within an entity does not mean that it is intended for multiple linguistic audiences. An example would be a beginner’s language primer, such as “A First Lesson in Latin,” which is clearly intended to be used by an English-literate audience. In this case, the Content-Language would properly only include “en.”

Content-Language MAY be applied to any media type—it is not limited to textual documents.

14.13. Content-Length

The Content-Length entity-header field indicates the size of the entity-body, in a decimal number of OCTETs, sent to the recipient or, in the case of the HEAD method, the size of the entity-body that would have been sent had the request been a GET.

Content-Length = "Content-Length" ":" 1*DIGIT

An example is

Content-Length: 3495

Applications SHOULD use this field to indicate the transfer-length of the message-body, unless this is prohibited by the rules in section 4.4.

Any Content-Length greater than or equal to zero is a valid value. Section 4.4 describes how to determine the length of a message-body if a Content-Length is not given.

Note that the meaning of this field is significantly different from the corresponding definition in MIME, where it is an optional field used within the “message/external-body” content-type. In HTTP, it SHOULD be sent whenever the message’s length can be determined prior to being transferred, unless this is prohibited by the rules in section 4.4.

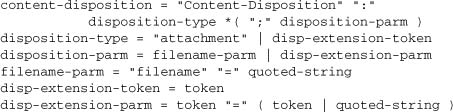

14.14. Content-Location

The Content-Location entity-header field MAY be used to supply the resource location for the entity enclosed in the message when that entity is accessible from a location separate from the requested resource’s URI. A server SHOULD provide a Content-Location for the variant corresponding to the response entity; especially in the case where a resource has multiple entities associated with it, and those entities actually have separate locations by which they might be individually accessed, the server SHOULD provide a Content-Location for the particular variant which is returned.

![]()

The value of Content-Location also defines the base URI for the entity.

The Content-Location value is not a replacement for the original requested URI; it is only a statement of the location of the resource corresponding to this particular entity at the time of the request. Future requests MAY specify the Content-Location URI as the request-URI if the desire is to identify the source of that particular entity.

A cache cannot assume that an entity with a Content-Location different from the URI used to retrieve it can be used to respond to later requests on that Content-Location URI. However, the Content-Location can be used to differentiate between multiple entities retrieved from a single requested resource, as described in section 13.6.

If the Content-Location is a relative URI, the relative URI is interpreted relative to the Request-URI.

The meaning of the Content-Location header in PUT or POST requests is undefined; servers are free to ignore it in those cases.

14.15. Content-MD5

The Content-MD5 entity-header field, as defined in RFC 1864 [23], is an MD5 digest of the entity-body for the purpose of providing an end-to-end message integrity check (MIC) of the entity-body. (Note: A MIC is good for detecting accidental modification of the entity-body in transit, but is not proof against malicious attacks.)

![]()

The Content-MD5 header field MAY be generated by an origin server or client to function as an integrity check of the entity-body. Only origin servers or clients MAY generate the Content-MD5 header field; proxies and gateways MUST NOT generate it, as this would defeat its value as an end-to-end integrity check. Any recipient of the entity-body, including gateways and proxies, MAY check that the digest value in this header field matches that of the entity-body as received.

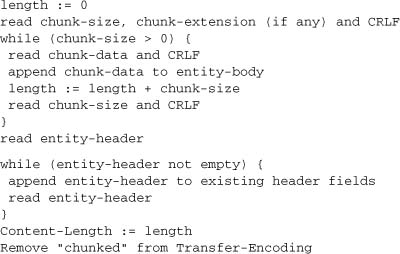

The MD5 digest is computed based on the content of the entity-body, including any content-coding that has been applied, but not including any transfer-encoding applied to the message-body. If the message is received with a transfer-encoding, that encoding MUST be removed prior to checking the Content-MD5 value against the received entity.

This has the result that the digest is computed on the octets of the entity-body exactly as, and in the order that, they would be sent if no transfer-encoding were being applied.

HTTP extends RFC 1864 to permit the digest to be computed for MIME composite media-types (e.g., multipart/* and message/rfc822), but this does not change how the digest is computed as defined in the preceding paragraph.

There are several consequences of this. The entity-body for composite types MAY contain many body-parts, each with its own MIME and HTTP headers (including Content-MD5, Content-Transfer-Encoding, and Content-Encoding headers). If a body-part has a Content-Transfer-Encoding or Content-Encoding header, it is assumed that the content of the body-part has had the encoding applied, and the body-part is included in the Content-MD5 digest as is—i.e., after the application. The Transfer-Encoding header field is not allowed within body-parts.

Conversion of all line breaks to CRLF MUST NOT be done before computing or checking the digest: The line break convention used in the text actually transmitted MUST be left unaltered when computing the digest.

Note: While the definition of Content-MD5 is exactly the same for HTTP as in RFC 1864 for MIME entity-bodies, there are several ways in which the application of Content-MD5 to HTTP entity-bodies differs from its application to MIME entity-bodies. One is that HTTP, unlike MIME, does not use Content-Transfer-Encoding, and does use Transfer-Encoding and Content-Encoding. Another is that HTTP more frequently uses binary content types than MIME, so it is worth noting that, in such cases, the byte order used to compute the digest is the transmission byte order defined for the type. Lastly, HTTP allows transmission of text types with any of several line break conventions and not just the canonical form using CRLF.

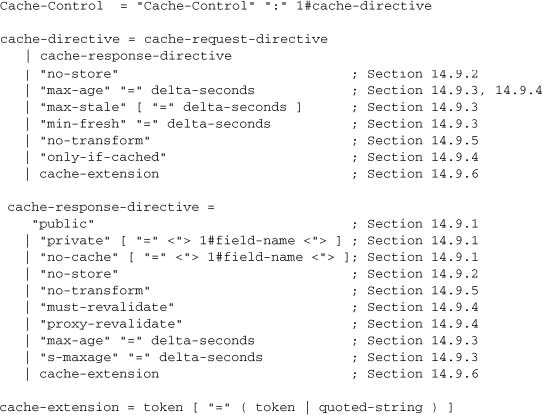

14.16. Content-Range

The Content-Range entity-header is sent with a partial entity-body to specify where in the full entity-body the partial body should be applied. Range units are defined in section 3.12.

The header SHOULD indicate the total length of the full entity-body, unless this length is unknown or difficult to determine. The asterisk “*” character means that the instance-length is unknown at the time when the response was generated.

Unlike byte-ranges-specifier values (see section 14.35.1), a byte-range-resp-spec MUST only specify one range, and MUST contain absolute byte positions for both the first and last byte of the range.

A byte-content-range-spec with a byte-range-resp-spec whose last-byte-pos value is less than its first-byte-pos value, or whose instance-length value is less than or equal to its last-byte-pos value, is invalid. The recipient of an invalid byte-content-range-spec MUST ignore it and any content transferred along with it.

A server sending a response with status code 416 (Requested range not satisfiable) SHOULD include a Content-Range field with a byte-range-resp-spec of “*”. The instance-length specifies the current length of the selected resource. A response with status code 206 (Partial Content) MUST NOT include a Content-Range field with a byte-range-resp-spec of “*”.

Examples of byte-content-range-spec values, assuming that the entity contains a total of 1234 bytes:

- The first 500 bytes:

bytes 0-499/1234 - The second 500 bytes:

bytes 500-999/1234 - All except for the first 500 bytes:

bytes 500-1233/1234 - The last 500 bytes:

bytes 734-1233/1234

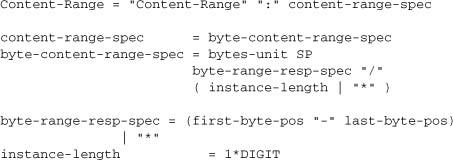

When an HTTP message includes the content of a single range (for example, a response to a request for a single range or a request for a set of ranges that overlap without any holes), this content is transmitted with a Content-Range header, and a Content-Length header showing the number of bytes actually transferred. For example,

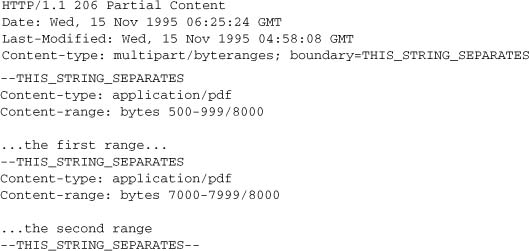

When an HTTP message includes the content of multiple ranges (for example, a response to a request for multiple non-overlapping ranges), these are transmitted as a multipart message. The multipart media type used for this purpose is “multipart/byteranges” as defined in appendix 19.2. See appendix 19.6.3 for a compatibility issue.

A response to a request for a single range MUST NOT be sent using the multipart/byteranges media type. A response to a request for multiple ranges, whose result is a single range, MAY be sent as a multipart/byteranges media type with one part. A client that cannot decode a multipart/byteranges message MUST NOT ask for multiple byte ranges in a single request.

When a client requests multiple byte ranges in one request, the server SHOULD return them in the order that they appeared in the request. If the server ignores a byte-range-spec because it is syntactically invalid, the server SHOULD treat the request as if the invalid Range header field did not exist. (Normally, this means return a 200 response containing the full entity).

If the server receives a request (other than one including an If-Range request-header field) with an unsatisfiable Range request-header field (that is, all of whose byte-range-spec values have a first-byte-pos value greater than the current length of the selected resource), it SHOULD return a response code of 416 (Requested range not satisfiable) (section 10.4.17).

Note: Clients cannot depend on servers to send a 416 (Requested range not satisfiable) response instead of a 200 (OK) response for an unsatisfiable Range request-header, since not all servers implement this request-header.

14.17. Content-Type

The Content-Type entity-header field indicates the media type of the entity-body sent to the recipient or, in the case of the HEAD method, the media type that would have been sent had the request been a GET.

Content-Type = "Content-Type" ":" media-type

Media types are defined in section 3.7. An example of the field is

Content-Type: text/html; charset=ISO-8859-4

Further discussion of methods for identifying the media type of an entity is provided in section 7.2.1.

14.18. Date

The Date general-header field represents the date and time at which the message originated, having the same semantics as orig-date in RFC 822. The field value is an HTTP-date, as described in section 3.3.1; it MUST be sent in RFC 1123 [8]-date format.

Date = "Date" ":" HTTP-date

An example is

Date: Tue, 15 Nov 1994 08:12:31 GMT

Origin servers MUST include a Date header field in all responses, except in these cases:

- If the response status code is 100 (Continue) or 101 (Switching Protocols), the response MAY include a Date header field, at the server’s option.

- If the response status code conveys a server error—e.g., 500 (Internal Server Error) or 503 (Service Unavailable)—and it is inconvenient or impossible to generate a valid Date.

- If the server does not have a clock that can provide a reasonable approximation of the current time, its responses MUST NOT include a Date header field. In this case, the rules in section 14.18.1 MUST be followed.

A received message that does not have a Date header field MUST be assigned one by the recipient if the message will be cached by that recipient or gatewayed via a protocol which requires a Date. An HTTP implementation without a clock MUST NOT cache responses without revalidating them on every use. An HTTP cache, especially a shared cache, SHOULD use a mechanism, such as NTP [28], to synchronize its clock with a reliable external standard.

Clients SHOULD only send a Date header field in messages that include an entity-body, as in the case of the PUT and POST requests, and even then it is optional. A client without a clock MUST NOT send a Date header field in a request.

The HTTP-date sent in a Date header SHOULD NOT represent a date and time subsequent to the generation of the message. It SHOULD represent the best available approximation of the date and time of message generation, unless the implementation has no means of generating a reasonably accurate date and time. In theory, the date ought to represent the moment just before the entity is generated. In practice, the date can be generated at any time during the message origination without affecting its semantic value.

14.18.1. Clockless Origin Server Operation

Some origin server implementations might not have a clock available. An origin server without a clock MUST NOT assign Expires or Last-Modified values to a response, unless these values were associated with the resource by a system or user with a reliable clock. It MAY assign an Expires value that is known, at or before server configuration time, to be in the past (this allows “pre-expiration” of responses without storing separate Expires values for each resource).

14.19. ETag

The ETag response-header field provides the current value of the entity tag for the requested variant. The headers used with entity tags are described in sections 14.24, 14.26, and 14.44. The entity tag MAY be used for comparison with other entities from the same resource (see section 13.3.3).

ETag = "ETag" ":" entity-tag

Examples:

![]()

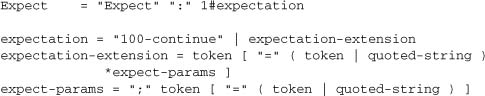

14.20. Expect

The Expect request-header field is used to indicate that particular server behaviors are required by the client.

A server that does not understand or is unable to comply with any of the expectation values in the Expect field of a request MUST respond with appropriate error status. The server MUST respond with a 417 (Expectation Failed) status if any of the expectations cannot be met or, if there are other problems with the request, some other 4xx status.

This header field is defined with extensible syntax to allow for future extensions. If a server receives a request containing an Expect field that includes an expectation-extension that it does not support, it MUST respond with a 417 (Expectation Failed) status.

Comparison of expectation values is case-insensitive for unquoted tokens (including the 100-continue token), and is case-sensitive for quoted-string expectation-extensions.

The Expect mechanism is hop-by-hop; that is, an HTTP/1.1 proxy MUST return a 417 (Expectation Failed) status if it receives a request with an expectation that it cannot meet. However, the Expect request-header itself is end-to-end; it MUST be forwarded if the request is forwarded.

Many older HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1 applications do not understand the Expect header.

See section 8.2.3 for the use of the 100 (Continue) status.

14.21. Expires

The Expires entity-header field gives the date/time after which the response is considered stale. A stale cache entry may not normally be returned by a cache (either a proxy cache or a user agent cache) unless it is first validated with the origin server (or with an intermediate cache that has a fresh copy of the entity). See section 13.2 for further discussion of the expiration model.

The presence of an Expires field does not imply that the original resource will change or cease to exist at, before, or after that time.

The format is an absolute date and time as defined by HTTP-date in section 3.3.1; it MUST be in RFC 1123 date format:

Expires = "Expires" ":" HTTP-date

An example of its use is

Expires: Thu, 01 Dec 1994 16:00:00 GMT

Note: If a response includes a Cache-Control field with the max-age directive (see section 14.9.3), that directive overrides the Expires field.

HTTP/1.1 clients and caches MUST treat other invalid date formats, especially including the value “0”, as in the past (i.e., “already expired”).

To mark a response as “already expired,” an origin server sends an Expires date that is equal to the Date header value. (See the rules for expiration calculations in section 13.2.4.)

To mark a response as “never expires,” an origin server sends an Expires date approximately one year from the time the response is sent. HTTP/1.1 servers SHOULD NOT send Expires dates more than one year in the future.

The presence of an Expires header field with a date value of some time in the future on a response that otherwise would by default be non-cacheable indicates that the response is cacheable, unless indicated otherwise by a Cache-Control header field (section 14.9).

14.22. From

The From request-header field, if given, SHOULD contain an Internet e-mail address for the human user who controls the requesting user agent. The address SHOULD be machine-usable, as defined by “mailbox” in RFC 822 [9] as updated by RFC 1123 [8]:

From = "From" ":" mailbox

An example is

From: [email protected]

This header field MAY be used for logging purposes and as a means for identifying the source of invalid or unwanted requests. It SHOULD NOT be used as an insecure form of access protection. The interpretation of this field is that the request is being performed on behalf of the person given, who accepts responsibility for the method performed. In particular, robot agents SHOULD include this header so that the person responsible for running the robot can be contacted if problems occur on the receiving end.

The Internet e-mail address in this field MAY be separate from the Internet host which issued the request. For example, when a request is passed through a proxy, the original issuer’s address SHOULD be used.

The client SHOULD NOT send the From header field without the user’s approval, as it might conflict with the user’s privacy interests or their site’s security policy. It is strongly recommended that the user be able to disable, enable, and modify the value of this field at any time prior to a request.

14.23. Host

The Host request-header field specifies the Internet host and port number of the resource being requested, as obtained from the original URI given by the user or referring resource (generally an HTTP URL, as described in section 3.2.2). The Host field value MUST represent the naming authority of the origin server or gateway given by the original URL. This allows the origin server or gateway to differentiate between internally ambiguous URLs, such as the root “/” URL of a server for multiple host names on a single IP address.

Host = "Host" ":" host [ ":" port ] ; Section 3.2.2

A “host” without any trailing port information implies the default port for the service requested (e.g., “80” for an HTTP URL). For example, a request on the origin server for <http://www.w3.org/pub/WWW/> would properly include

![]()

A client MUST include a Host header field in all HTTP/1.1 request messages. If the requested URI does not include an Internet host name for the service being requested, then the Host header field MUST be given with an empty value. An HTTP/1.1 proxy MUST ensure that any request message it forwards does contain an appropriate Host header field that identifies the service being requested by the proxy. All Internet-based HTTP/1.1 servers MUST respond with a 400 (Bad Request) status code to any HTTP/1.1 request message which lacks a Host header field.

See sections 5.2 and 19.6.1.1 for other requirements relating to Host.

14.24. If-Match

The If-Match request-header field is used with a method to make it conditional. A client that has one or more entities previously obtained from the resource can verify that one of those entities is current by including a list of their associated entity tags in the If-Match header field. Entity tags are defined in section 3.11. The purpose of this feature is to allow efficient updates of cached information with a minimum amount of transaction overhead. It is also used, on updating requests, to prevent inadvertent modification of the wrong version of a resource. As a special case, the value “*” matches any current entity of the resource.

If-Match = "If-Match" ":" ( "*" | 1#entity-tag )

If any of the entity tags match the entity tag of the entity that would have been returned in the response to a similar GET request (without the If-Match header) on that resource, or if “*” is given and any current entity exists for that resource, then the server MAY perform the requested method as if the If-Match header field did not exist.

A server MUST use the strong comparison function (see section 13.3.3) to compare the entity tags in If-Match.

If none of the entity tags match, or if “*” is given and no current entity exists, the server MUST NOT perform the requested method, and MUST return a 412 (Precondition Failed) response. This behavior is most useful when the client wants to prevent an updating method, such as PUT, from modifying a resource that has changed since the client last retrieved it.

If the request would, without the If-Match header field, result in anything other than a 2xx or 412 status, then the If-Match header MUST be ignored.

The meaning of “If-Match: *” is that the method SHOULD be performed if the representation selected by the origin server (or by a cache, possibly using the Vary mechanism; see section 14.44) exists, and MUST NOT be performed if the representation does not exist.

A request intended to update a resource (e.g., a PUT) MAY include an If-Match header field to signal that the request method MUST NOT be applied if the entity corresponding to the If-Match value (a single entity tag) is no longer a representation of that resource. This allows the user to indicate that they do not wish the request to be successful if the resource has been changed without their knowledge. Examples:

![]()

The result of a request having both an If-Match header field and either an If-None-Match or an If-Modified-Since header field is undefined by this specification.

14.25. If-Modified-Since

The If-Modified-Since request-header field is used with a method to make it conditional: If the requested variant has not been modified since the time specified in this field, an entity will not be returned from the server; instead, a 304 (not modified) response will be returned without any message-body.

If-Modified-Since = "If-Modified-Since" ":" HTTP-date

An example of the field is

If-Modified-Since: Sat, 29 Oct 1994 19:43:31 GMT

A GET method with an If-Modified-Since header and no Range header requests that the identified entity be transferred only if it has been modified since the date given by the If-Modified-Since header. The algorithm for determining this includes the following cases:

(a) If the request would normally result in anything other than a 200 (OK) status, or if the passed If-Modified-Since date is invalid, the response is exactly the same as for a normal GET. A date which is later than the server’s current time is invalid.

(b) If the variant has been modified since the If-Modified-Since date, the response is exactly the same as for a normal GET.

(c) If the variant has not been modified since a valid If-Modified-Since date, the server SHOULD return a 304 (Not Modified) response.

The purpose of this feature is to allow efficient updates of cached information with a minimum amount of transaction overhead.

Note: The Range request-header field modifies the meaning of If-Modified-Since; see section 14.35 for full details.

Note: If-Modified-Since times are interpreted by the server, whose clock might not be synchronized with the client.

Note: When handling an If-Modified-Since header field, some servers will use an exact date comparison function, rather than a less-than function, for deciding whether to send a 304 (Not Modified) response. To get the best results when sending an If-Modified-Since header field for cache validation, clients are advised to use the exact date string received in a previous Last-Modified header field whenever possible.

Note: If a client uses an arbitrary date in the If-Modified-Since header instead of a date taken from the Last-Modified header for the same request, the client should be aware of the fact that this date is interpreted in the server’s understanding of time. The client should consider unsynchronized clocks and rounding problems due to the different encodings of time between the client and server. This includes the possibility of race conditions if the document has changed between the time it was first requested and the If-Modified-Since date of a subsequent request, and the possibility of clock-skew-related problems if the If-Modified-Since date is derived from the client’s clock without correction to the server’s clock. Corrections for different time bases between client and server are at best approximate due to network latency.

The result of a request having both an If-Modified-Since header field and either an If-Match or an If-Unmodified-Since header field is undefined by this specification.

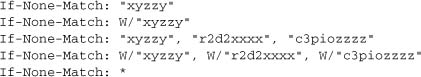

14.26. If-None-Match

The If-None-Match request-header field is used with a method to make it conditional. A client that has one or more entities previously obtained from the resource can verify that none of those entities is current by including a list of their associated entity tags in the If-None-Match header field. The purpose of this feature is to allow efficient updates of cached information with a minimum amount of transaction overhead. It is also used to prevent a method (e.g., PUT) from inadvertently modifying an existing resource when the client believes that the resource does not exist.

As a special case, the value “*” matches any current entity of the resource.

If-None-Match = "If-None-Match" ":" ( "*" | 1#entity-tag )

If any of the entity tags match the entity tag of the entity that would have been returned in the response to a similar GET request (without the If-None-Match header) on that resource, or if “*” is given and any current entity exists for that resource, then the server MUST NOT perform the requested method, unless required to do so because the resource’s modification date fails to match that supplied in an If-Modified-Since header field in the request. Instead, if the request method was GET or HEAD, the server SHOULD respond with a 304 (Not Modified) response, including the cache-related header fields (particularly ETag) of one of the entities that matched. For all other request methods, the server MUST respond with a status of 412 (Precondition Failed).

See section 13.3.3 for rules on how to determine if two entities tags match. The weak comparison function can only be used with GET or HEAD requests.

If none of the entity tags match, then the server MAY perform the requested method as if the If-None-Match header field did not exist, but MUST also ignore any If-Modified-Since header field(s) in the request. That is, if no entity tags match, then the server MUST NOT return a 304 (Not Modified) response.

If the request would, without the If-None-Match header field, result in anything other than a 2xx or 304 status, then the If-None-Match header MUST be ignored. (See section 13.3.4 for a discussion of server behavior when both If-Modified-Since and If-None-Match appear in the same request.)

The meaning of “If-None-Match: *” is that the method MUST NOT be performed if the representation selected by the origin server (or by a cache, possibly using the Vary mechanism; see section 14.44) exists, and SHOULD be performed if the representation does not exist. This feature is intended to be useful in preventing races between PUT operations.

Examples:

The result of a request having both an If-None-Match header field and either an If-Match or an If-Unmodified-Since header field is undefined by this specification.

14.27. If-Range

If a client has a partial copy of an entity in its cache, and wishes to have an up-to-date copy of the entire entity in its cache, it could use the Range request-header with a conditional GET (using either or both of If-Unmodified-Since and If-Match.) However, if the condition fails because the entity has been modified, the client would then have to make a second request to obtain the entire current entity-body.

The If-Range header allows a client to “short-circuit” the second request. Informally, its meaning is “If the entity is unchanged, send me the part(s) that I am missing; otherwise, send me the entire new entity.”

If-Range = "If-Range" ":" ( entity-tag | HTTP-date )

If the client has no entity tag for an entity but does have a Last-Modified date, it MAY use that date in an If-Range header. (The server can distinguish between a valid HTTP-date and any form of entity-tag by examining no more than two characters.) The If-Range header SHOULD only be used together with a Range header, and MUST be ignored if the request does not include a Range header or if the server does not support the subrange operation.

If the entity tag given in the If-Range header matches the current entity tag for the entity, then the server SHOULD provide the specified subrange of the entity using a 206 (Partial content) response. If the entity tag does not match, then the server SHOULD return the entire entity using a 200 (OK) response.

14.28. If-Unmodified-Since

The If-Unmodified-Since request-header field is used with a method to make it conditional. If the requested resource has not been modified since the time specified in this field, the server SHOULD perform the requested operation as if the If-Unmodified-Since header were not present.

If the requested variant has been modified since the specified time, the server MUST NOT perform the requested operation, and MUST return a 412 (Precondition Failed).

If-Unmodified-Since = "If-Unmodified-Since" ":" HTTP-date

An example of the field is

If-Unmodified-Since: Sat, 29 Oct 1994 19:43:31 GMT

If the request normally (i.e., without the If-Unmodified-Since header) would result in anything other than a 2xx or 412 status, the If-Unmodified-Since header SHOULD be ignored.

If the specified date is invalid, the header is ignored.

The result of a request having both an If-Unmodified-Since header field and either an If-None-Match or an If-Modified-Since header field is undefined by this specification.

14.29. Last-Modified

The Last-Modified entity-header field indicates the date and time at which the origin server believes the variant was last modified.

Last-Modified = "Last-Modified" ":" HTTP-date

An example of its use is

Last-Modified: Tue, 15 Nov 1994 12:45:26 GMT

The exact meaning of this header field depends on the implementation of the origin server and the nature of the original resource. For files, it may be just the file system last-modified time. For entities with dynamically included parts, it may be the most recent of the set of last-modify times for its component parts. For database gateways, it may be the last-update time stamp of the record. For virtual objects, it may be the last time the internal state changed.

An origin server MUST NOT send a Last-Modified date which is later than the server’s time of message origination. In such cases, where the resource’s last modification would indicate some time in the future, the server MUST replace that date with the message origination date.

An origin server SHOULD obtain the Last-Modified value of the entity as close as possible to the time that it generates the Date value of its response. This allows a recipient to make an accurate assessment of the entity’s modification time, especially if the entity changes near the time that the response is generated.

HTTP/1.1 servers SHOULD send Last-Modified whenever feasible.

14.30. Location

The Location response-header field is used to redirect the recipient to a location other than the Request-URI for completion of the request or identification of a new resource. For 201 (Created) responses, the Location is that of the new resource which was created by the request. For 3xx responses, the location SHOULD indicate the server’s preferred URI for automatic redirection to the resource. The field value consists of a single absolute URI.

Location = "Location" ":" absoluteURI

An example is

Location: http://www.w3.org/pub/WWW/People.html

Note: The Content-Location header field (section 14.14) differs from Location in that the Content-Location identifies the original location of the entity enclosed in the request. It is therefore possible for a response to contain header fields for both Location and Content-Location. Also see section 13.10 for cache requirements of some methods.

14.31. Max-Forwards

The Max-Forwards request-header field provides a mechanism with the TRACE (section 9.8) and OPTIONS (section 9.2) methods to limit the number of proxies or gateways that can forward the request to the next inbound server. This can be useful when the client is attempting to trace a request chain which appears to be failing or looping in mid-chain.

Max-Forwards = "Max-Forwards" ":" 1*DIGIT

The Max-Forwards value is a decimal integer indicating the remaining number of times this request message may be forwarded.

Each proxy or gateway recipient of a TRACE or OPTIONS request containing a Max-Forwards header field MUST check and update its value prior to forwarding the request. If the received value is zero (0), the recipient MUST NOT forward the request; instead, it MUST respond as the final recipient. If the received Max-Forwards value is greater than zero, then the forwarded message MUST contain an updated Max-Forwards field with a value decremented by one (1).

The Max-Forwards header field MAY be ignored for all other methods defined by this specification and for any extension methods for which it is not explicitly referred to as part of that method definition.

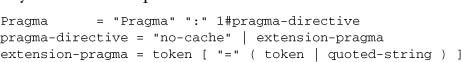

14.32. Pragma

The Pragma general-header field is used to include implementation-specific directives that might apply to any recipient along the request/response chain. All pragma directives specify optional behavior from the viewpoint of the protocol; however, some systems MAY require that behavior be consistent with the directives.

When the no-cache directive is present in a request message, an application SHOULD forward the request toward the origin server even if it has a cached copy of what is being requested. This pragma directive has the same semantics as the nocache cache-directive (see section 14.9) and is defined here for backward compatibility with HTTP/1.0. Clients SHOULD include both header fields when a no-cache request is sent to a server not known to be HTTP/1.1 compliant.

Pragma directives MUST be passed through by a proxy or gateway application, regardless of their significance to that application, since the directives might be applicable to all recipients along the request/response chain. It is not possible to specify a pragma for a specific recipient; however, any pragma directive not relevant to a recipient SHOULD be ignored by that recipient.

HTTP/1.1 caches SHOULD treat “Pragma: no-cache” as if the client had sent “Cache-Control: no-cache.” No new Pragma directives will be defined in HTTP.

Note: Because the meaning of “Pragma: no-cache” as a response header field is not actually specified, it does not provide a reliable replacement for “Cache-Control: no-cache” in a response.

14.33. Proxy-Authenticate

The Proxy-Authenticate response-header field MUST be included as part of a 407 (Proxy Authentication Required) response. The field value consists of a challenge that indicates the authentication scheme and parameters applicable to the proxy for this Request-URI.

Proxy-Authenticate = "Proxy-Authenticate" ":" 1#challenge

The HTTP access authentication process is described in “HTTP Authentication: Basic and Digest Access Authentication” [43]. Unlike WWW-Authenticate, the Proxy-Authenticate header field applies only to the current connection and SHOULD NOT be passed on to downstream clients. However, an intermediate proxy might need to obtain its own credentials by requesting them from the downstream client, which in some circumstances will appear as if the proxy is forwarding the Proxy-Authenticate header field.

14.34. Proxy-Authorization

The Proxy-Authorization request-header field allows the client to identify itself (or its user) to a proxy which requires authentication. The Proxy-Authorization field value consists of credentials containing the authentication information of the user agent for the proxy and/or realm of the resource being requested.

Proxy-Authorization = "Proxy-Authorization" ":" credentials

The HTTP access authentication process is described in “HTTP Authentication: Basic and Digest Access Authentication” [43]. Unlike Authorization, the Proxy-Authorization header field applies only to the next outbound proxy that demanded authentication using the Proxy-Authenticate field. When multiple proxies are used in a chain, the Proxy-Authorization header field is consumed by the first outbound proxy that was expecting to receive credentials. A proxy MAY relay the credentials from the client request to the next proxy if that is the mechanism by which the proxies cooperatively authenticate a given request.

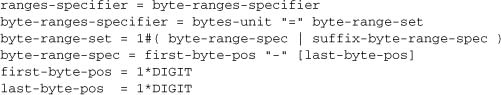

14.35. Range

14.35.1. Byte Ranges

Since all HTTP entities are represented in HTTP messages as sequences of bytes, the concept of a byte range is meaningful for any HTTP entity. (However, not all clients and servers need to support byte-range operations.)

Byte-range specifications in HTTP apply to the sequence of bytes in the entity-body (not necessarily the same as the message-body).

A byte-range operation MAY specify a single range of bytes, or a set of ranges within a single entity.

The first-byte-pos value in a byte-range-spec gives the byte offset of the first byte in a range. The last-byte-pos value gives the byte offset of the last byte in the range; that is, the byte positions specified are inclusive. Byte offsets start at zero.

If the last-byte-pos value is present, it MUST be greater than or equal to the first-byte-pos in that byte-range-spec, or the byte-range-spec is syntactically invalid. The recipient of a byte-range-set that includes one or more syntactically invalid byte-range-spec values MUST ignore the header field that includes that byte-range-set.

If the last-byte-pos value is absent, or if the value is greater than or equal to the current length of the entity-body, the last-byte-pos is taken to be equal to one less than the current length of the entity-body in bytes.

By its choice of last-byte-pos, a client can limit the number of bytes retrieved without knowing the size of the entity.

![]()

A suffix-byte-range-spec is used to specify the suffix of the entity-body, of a length given by the suffix-length value. (That is, this form specifies the last N bytes of an entity-body.) If the entity is shorter than the specified suffix-length, the entire entity-body is used.

If a syntactically valid byte-range-set includes at least one byte-range-spec whose first-byte-pos is less than the current length of the entity-body, or at least one suffix-byte-range-spec with a non-zero suffix-length, then the byte-range-set is satisfiable. Otherwise, the byte-range-set is unsatisfiable. If the byte-range-set is unsatisfiable, the server SHOULD return a response with a status of 416 (Requested range not satisfiable). Otherwise, the server SHOULD return a response with a status of 206 (Partial Content) containing the satisfiable ranges of the entity-body.

Examples of byte-ranges-specifier values (assuming an entity-body of length 10000):

- The first 500 bytes (byte offsets 0-499, inclusive): bytes=0-499

- The second 500 bytes (byte offsets 500-999, inclusive): bytes=500-999

- The final 500 bytes (byte offsets 9500-9999, inclusive): bytes=-500

- Or bytes=9500-

- The first and last bytes only (bytes 0 and 9999): bytes=0-0,-1

- Several legal but not canonical specifications of the second 500 bytes (byte offsets 500-999, inclusive):

![]()

14.35.2. Range Retrieval Requests

HTTP retrieval requests using conditional or unconditional GET methods MAY request one or more subranges of the entity, instead of the entire entity, using the Range request header, which applies to the entity returned as the result of the request:

Range = "Range" ":" ranges-specifier

A server MAY ignore the Range header. However, HTTP/1.1 origin servers and intermediate caches ought to support byte ranges when possible, since Range supports efficient recovery from partially failed transfers and supports efficient partial retrieval of large entities.

If the server supports the Range header and the specified range or ranges are appropriate for the entity:

- The presence of a Range header in an unconditional GET modifies what is returned if the GET is otherwise successful. In other words, the response carries a status code of 206 (Partial Content) instead of 200 (OK).

- The presence of a Range header in a conditional GET (a request using one or both of If-Modified-Since and If-None-Match, or one or both of If-Unmodified-Since and If-Match) modifies what is returned if the GET is otherwise successful and the condition is true. It does not affect the 304 (Not Modified) response returned if the conditional is false.

In some cases, it might be more appropriate to use the If-Range header (see section 14.27) in addition to the Range header.

If a proxy that supports ranges receives a Range request, forwards the request to an inbound server, and receives an entire entity in reply, it SHOULD only return the requested range to its client. It SHOULD store the entire received response in its cache if that is consistent with its cache allocation policies.

14.36. Referer

The Referer [sic] request-header field allows the client to specify, for the server’s benefit, the address (URI) of the resource from which the Request-URI was obtained (the “referrer,” although the header field is misspelled.) The Referer request-header allows a server to generate lists of back-links to resources for interest, logging, optimized caching, etc. It also allows obsolete or mistyped links to be traced for maintenance. The Referer field MUST NOT be sent if the Request-URI was obtained from a source that does not have its own URI, such as input from the user keyboard.

Referer = "Referer" ":" ( absoluteURI | relativeURI )

Example:

Referer: http://www.w3.org/hypertext/DataSources/Overview.html

If the field value is a relative URI, it SHOULD be interpreted relative to the Request-URI. The URI MUST NOT include a fragment. See section 15.1.3 for security considerations.

14.37. Retry-After

The Retry-After response-header field can be used with a 503 (Service Unavailable) response to indicate how long the service is expected to be unavailable to the requesting client. This field MAY also be used with any 3xx (Redirection) response to indicate the minimum time the user agent is asked wait before issuing the redirected request. The value of this field can be either an HTTP-date or an integer number of seconds (in decimal) after the time of the response.

Retry-After = "Retry-After" ":" ( HTTP-date | delta-seconds )

Two examples of its use are

![]()

In the latter example, the delay is 2 minutes.

14.38. Server

The Server response-header field contains information about the software used by the origin server to handle the request. The field can contain multiple product tokens (section 3.8) and comments identifying the server and any significant subproducts. The product tokens are listed in order of their significance for identifying the application.

Server = "Server" ":" 1*( product | comment )

Example:

Server: CERN/3.0 libwww/2.17

If the response is being forwarded through a proxy, the proxy application MUST NOT modify the Server response-header. Instead, it SHOULD include a Via field (as described in section 14.45).

Note: Revealing the specific software version of the server might allow the server machine to become more vulnerable to attacks against software that is known to contain security holes. Server implementers are encouraged to make this field a configurable option.

14.39. TE

The TE request-header field indicates what extension transfer-codings it is willing to accept in the response and whether or not it is willing to accept trailer fields in a chunked transfer-coding. Its value may consist of the keyword “trailers” and/or a comma-separated list of extension transfer-coding names with optional accept parameters (as described in section 3.6).

![]()

The presence of the keyword “trailers” indicates that the client is willing to accept trailer fields in a chunked transfer-coding, as defined in section 3.6.1. This keyword is reserved for use with transfer-coding values even though it does not itself represent a transfer-coding.

Examples of its use are

![]()

The TE header field only applies to the immediate connection. Therefore, the keyword MUST be supplied within a Connection header field (section 14.10) whenever TE is present in an HTTP/1.1 message.

A server tests whether a transfer-coding is acceptable, according to a TE field, using these rules:

- The “chunked” transfer-coding is always acceptable. If the keyword “trailers” is listed, the client indicates that it is willing to accept trailer fields in the chunked response on behalf of itself and any downstream clients. The implication is that, if given, the client is stating that either all downstream clients are willing to accept trailer fields in the forwarded response, or that it will attempt to buffer the response on behalf of downstream recipients.

Note: HTTP/1.1 does not define any means to limit the size of a chunked response such that a client can be assured of buffering the entire response.

- If the transfer-coding being tested is one of the transfer-codings listed in the TE field, then it is acceptable unless it is accompanied by a qvalue of 0. (As defined in section 3.9, a qvalue of 0 means “not acceptable.”)

- If multiple transfer-codings are acceptable, then the acceptable transfer-coding with the highest non-zero qvalue is preferred. The “chunked” transfer-coding always has a qvalue of 1.

If the TE field-value is empty or if no TE field is present, the only transfer-coding is “chunked.” A message with no transfer-coding is always acceptable.

14.40. Trailer

The Trailer general field value indicates that the given set of header fields is present in the trailer of a message encoded with chunked transfer-coding.

Trailer = "Trailer" ":" 1#field-name

An HTTP/1.1 message SHOULD include a Trailer header field in a message using chunked transfer-coding with a non-empty trailer. Doing so allows the recipient to know which header fields to expect in the trailer.

If no Trailer header field is present, the trailer SHOULD NOT include any header fields. See section 3.6.1 for restrictions on the use of trailer fields in a “chunked” transfer-coding.

Message header fields listed in the Trailer header field MUST NOT include the following header fields:

- Transfer-Encoding

- Content-Length

- Trailer

14.41. Transfer-Encoding

The Transfer-Encoding general-header field indicates what (if any) type of transformation has been applied to the message body in order to safely transfer it between the sender and the recipient. This differs from the content-coding in that the transfer-coding is a property of the message, not of the entity.

Transfer-Encoding = "Transfer-Encoding" ":" 1#transfer-coding

Transfer-codings are defined in section 3.6. An example is

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

If multiple encodings have been applied to an entity, the transfer-codings MUST be listed in the order in which they were applied. Additional information about the encoding parameters MAY be provided by other entity-header fields not defined by this specification.

Many older HTTP/1.0 applications do not understand the Transfer-Encoding header.

14.42. Upgrade

The Upgrade general-header allows the client to specify what additional communication protocols it supports and would like to use if the server finds it appropriate to switch protocols. The server MUST use the Upgrade header field within a 101 (Switching Protocols) response to indicate which protocol(s) are being switched.

Upgrade = "Upgrade" ":" 1#product

Example:

Upgrade: HTTP/2.0, SHTTP/1.3, IRC/6.9, RTA/x11

The Upgrade header field is intended to provide a simple mechanism for transition from HTTP/1.1 to some other, incompatible protocol. It does so by allowing the client to advertise its desire to use another protocol, such as a later version of HTTP with a higher major version number, even though the current request has been made using HTTP/1.1. This eases the difficult transition between incompatible protocols by allowing the client to initiate a request in the more commonly supported protocol while indicating to the server that it would like to use a “better” protocol if available (where “better” is determined by the server, possibly according to the nature of the method and/or resource being requested).

The Upgrade header field only applies to switching application-layer protocols upon the existing transport-layer connection. Upgrade cannot be used to insist on a protocol change; its acceptance and use by the server is optional. The capabilities and nature of the application-layer communication after the protocol change are entirely dependent upon the new protocol chosen, although the first action after changing the protocol MUST be a response to the initial HTTP request containing the Upgrade header field.

The Upgrade header field only applies to the immediate connection. Therefore, the upgrade keyword MUST be supplied within a Connection header field (section 14.10) whenever Upgrade is present in an HTTP/1.1 message.

The Upgrade header field cannot be used to indicate a switch to a protocol on a different connection. For that purpose, it is more appropriate to use a 301, 302, 303, or 305 redirection response.

This specification only defines the protocol name “HTTP” for use by the family of Hypertext Transfer Protocols, as defined by the HTTP version rules of section 3.1 and future updates to this specification. Any token can be used as a protocol name; however, it will only be useful if both the client and the server associate the name with the same protocol.

14.43. User-Agent

The User-Agent request-header field contains information about the user agent originating the request. This is for statistical purposes, the tracing of protocol violations, and automated recognition of user agents for the sake of tailoring responses to avoid particular user agent limitations. User agents SHOULD include this field with requests. The field can contain multiple product tokens (section 3.8) and comments identifying the agent and any subproducts which form a significant part of the user agent. By convention, the product tokens are listed in order of their significance for identifying the application.

User-Agent = "User-Agent" ":" 1*( product | comment )

Example:

User-Agent: CERN-LineMode/2.15 libwww/2.17b3

14.44. Vary

The Vary field value indicates the set of request-header fields that fully determines, while the response is fresh, whether a cache is permitted to use the response to reply to a subsequent request without revalidation. For non-cacheable or stale responses, the Vary field value advises the user agent about the criteria that were used to select the representation. A Vary field value of “*” implies that a cache cannot determine from the request headers of a subsequent request whether this response is the appropriate representation. See section 13.6 for use of the Vary header field by caches.

Vary = "Vary" ":" ( "*" | 1#field-name )

An HTTP/1.1 server SHOULD include a Vary header field with any cacheable response that is subject to server-driven negotiation. Doing so allows a cache to properly interpret future requests on that resource and informs the user agent about the presence of negotiation on that resource. A server MAY include a Vary header field with a non-cacheable response that is subject to server-driven negotiation, since this might provide the user agent with useful information about the dimensions over which the response varies at the time of the response.

A Vary field value consisting of a list of field-names signals that the representation selected for the response is based on a selection algorithm which considers ONLY the listed request-header field values in selecting the most appropriate representation. A cache MAY assume that the same selection will be made for future requests with the same values for the listed field-names, for the duration of time for which the response is fresh.

The field-names given are not limited to the set of standard request-header fields defined by this specification. Field-names are case-insensitive.

A Vary field value of “*” signals that unspecified parameters not limited to the request-headers (e.g., the network address of the client) play a role in the selection of the response representation. The “*” value MUST NOT be generated by a proxy server; it may only be generated by an origin server.

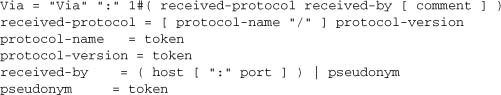

14.45. Via

The Via general-header field MUST be used by gateways and proxies to indicate the intermediate protocols and recipients between the user agent and the server on requests, and between the origin server and the client on responses. It is analogous to the “Received” field of RFC 822 [9] and is intended to be used for tracking message forwards, avoiding request loops, and identifying the protocol capabilities of all senders along the request/response chain.

The received-protocol indicates the protocol version of the message received by the server or client along each segment of the request/response chain. The received-protocol version is appended to the Via field value when the message is forwarded so that information about the protocol capabilities of upstream applications remains visible to all recipients.