CHAPTER 6

Listening Skills

— R.G. Nichols and L. A. Stevens

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand how listening is an essential component of communication and management.

- Know the internal and external causes of poor listening.

- Know some guidelines for improving listening skills.

- Understand how to craft reflective and clarifying responses that demonstrate good listening skills.

COMMUNICATION AT WORK

Picture yourself teaching a class on business research methods—not an equally interesting subject for all students. During the course of the lecture, you see that a girl in the last row is busy writing in her notebook, not even once looking towards you. Next to the wall, a student is reading silently from a book. In the middle row, a half-asleep boy struggles to keep his eyes open. Only in the front two rows do you find students paying attention to what you have been discussing. They have been looking towards you and have been also taking notes from time to time.

You have explained the causal relationship between two variables, A and B. You have given a few examples of this relationship from actual life. Now, to ascertain how much of what you have been discussing has been followed by the class, you ask some students about

Why is this so? They all have attended the same lecture. You were loud enough to reach everyone, clear enough to be understood, and logically ordered in your discourse. Then how did some students miss your point so completely? It seems as if they were not even present in the lecture.

The fact is that those who failed to answer you heard you, but did not listen to your exposition of the variables and their relationships. They heard you, for they could not fail to hear you. They were not deaf. But their minds did not absorb what you said.

WHAT IS LISTENING?

To listen is to pay thoughtful attention to what someone is saying. It is a deliberate act of attentively hearing a person speak. It is the mental process of paying undivided attention to what is heard. Listening is more than hearing, which is just the physical act of senses receiving sounds. Hearing involves the ears, but listening involves the ears, eyes, heart, and mind. It is rightly said that listening is an essential component of communication. Without this element, fruitful communication is not possible. Listening occurs when the receiver of the message wishes to learn, or be influence or changed by the message. When someone is interested in actively hearing, they are listening. Exhibit 6.1 shows the importance of listening in our daily lives.

Listening is more than hearing, which is just the physical act of our senses receiving sounds. Hearing involves our ears, but listening involves our ears, eyes, heart, and mind.

Exhibit 6.1

The Importance of Listening

Studies conducted since the 1930s reveal that 70 per cent of our waking time goes into communication. The pie chart below illustrates the activities that take up various portions of this 70 per cent:

Note that this break-up reflects the norms. The figures would differ from group to group. For example, for a group of young students, speaking would be lower than hearing (or listening), and their reading and writing figures will also be higher. For a group of teachers, speaking would be high.

How Do We Listen?

Listening is not passive. It is a deliberate act of concentrating on sound waves that the auditory nerve sends to the brain. As a first step in the listening process, the listener focuses his or her attention on what is essential in the communication. At the same time, he or she tries to understand, interpret, and register what is received. It is not easy to pay undivided attention to a speaker, and without giving proper attention to developing listening skills, many people remain poor listeners.

An Indian saying draws attention to the natural fact that we have two ears but one tongue. Hence, we should listen twice as much as we speak.

Listening, like speaking, reading, and writing, is a skill that can be dramatically improved through training. In this chapter therefore, we will discuss some basic things about listening such as the complete process from hearing to conceptualizing, causes for poor listening, and some techniques of improving listening as a voluntary behaviour.

1

Understand how listening is an essential component of communication and management.

Listening As a Management Tool

The Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English defines listening ‘considering what someone says and accepting their advice’. In this sense, far-sighted business heads and senior executives use careful listening to benefit from the valuable views, perceptions, and experiences of junior and middle level workers of the company. They often owe many an initiative or cost-cutting measure to suggestions given by juniors in informal sessions. By listening to what others say about a specific situation, that is by considering and accepting the advice of others, the company succeeds in taking the best possible decision and effectively implementing it.

An example of successful ‘Management by Listening’ is the case of Maruti Udyog, which has flourished using former Managing Director Jagdish Khattar’s innovative methods of seeking suggestions from employees.1 Maruti’s decision to showcase a concept car at Delhi’s annual Auto Expo was born out of an event called ‘Tea with the MD’. Almost every fortnight, Khattar used to get together with a group of young Maruti engineers and managers in an informal meeting that encouraged them to articulate their ideas for the company’s growth. Khattar’s purpose was to elicit valuable suggestions for Maruti’s growth by holding informal tea-sessions with his engineers and managers or by walking around at dealers’ conventions, urging his dealers to make suggestions for improving sales and distribution. This was how he hit upon a formula that saved the company nearly INR 4 million.

Realizing that dealers hesitated to express themselves in an open forum, Khattar urged each of them to put down three of their suggestions on a piece of paper. He said, ‘On the five-hour flight back from Bangkok to Delhi, I went through each and every sheet. Our dealers had made several suggestions on how we could de-bottleneck distribution. I realized that increasing the sales force and opening small dealership extensions in rural and semi-urban areas could easily cut down on investments’.

Khattar would routinely talk with and listen to youngsters before walking into his office. His example demonstrates how providing opportunities to others to express valuable suggestions holds the key to the successful management of problems.

THE PROCESS OF LISTENING

Listening is an integrated process, which consists of the following phases: undivided attention, hearing, understanding, interpreting, evaluating, empathizing and conceptualizing.

An explanation of these aspects of the process of listening would be helpful before proceeding. These phases do not occur in succession, but instead operate concurrently and in tandem. All aspects of oral verbal communication require one to focus on what is being said, understand it, and register it as part of one’s body of knowledge and experience.

- Undivided attention: Effective listening requires a certain frame of mind. The process of listening is rooted in attentively hearing the message. Undivided attention admits no distractions and no intrusive thoughts or ideas that are unrelated to the message. To concentrate on what is being said, an earnest listener would focus on the message and not let other things compete for his or her attention. The listener in this phase discriminates between thoughts, ideas, or images that belong in his or her focus of attention and those that float on its margin and must be kept from entering into conscious consideration.

- Hearing: Listening involves hearing distinct sounds and perceiving fine modulations in tone. The receiver recognizes the shape of words and intonation patterns. Familiarity with the sound of words and the spoken rhythm of speech contributes to the attentiveness of the listener. Pitch, voice modulations, and the quality of sound are equally important for hearing with the right attention.

- Understanding: A listener can hear words but must listen to know their intended meaning. Perfect communication is when the full meaning of what is said has been understood. This includes words, tone, and body talk. A good listener hears words, observes body movements, gestures, facial expressions, and eye movements, and notices variations in tone and pitch of voice. If the listener attends only to words without paying close attention to how they are said, he or she may be missing the real, intended meaning of those words.

- Interpreting: Understanding and interpretation follow the phase of hearing. The listener attempts to comprehend what is heard. Understanding the language may not be enough for fully comprehending the message and successfully participating in the act of communication. It should be accompanied by the ability to interpret what is communicated, which occurs when the listener takes account of his or her own knowledge and experience.

- Evaluating: Communication requires that the listener have the critical ability to see for himself or herself the value of what is being discussed or heard. It is only then that the listener can closely follow the argument. The evaluation of content is closely related to the listener’s own interest in what is being communicated.

- Empathizing: A sympathetic listener sees the speaker’s point of view. He or she may not agree with what is said, yet such a listener allows the other person to say what he or she wants to say.

- Conceptualizing: Conceptualization occurs when the listener finally assimilates what has been heard in the context of his or her own knowledge and experiences. This is why listening is not only important but also indispensable for perfect communication.

FACTORS THAT ADVERSELY AFFECT LISTENING

Listening is a voluntary behaviour that can be easily affected by internal or external factors that can act as barriers to good listening.

2

Know the internal and external causes of poor listening.

Lack of Concentration

Many times listeners are not able to concentrate on what is being heard. There may be several reasons for this. There could be external factors responsible for the inability to listen properly. For example, there may be noise inside the room or loud music being played nearby. This external noise can be shut off in several ways. But the internal factors within the listener’s mind that interference with concentration are more serious and difficult to avoid or manage. These can be overcome through practice once the listener is made aware that they are problematic.

Reasons for not concentrating include:

- Hearing faster than speaking: Humans normally talk at nearly 120 to 125 words per minute, but the brain is capable of receiving 500 to 600 words per minute. The listener’s brain, therefore, must deal with gaps between words, and this gap tends to be filled by other thoughts and images. This phenomenon interferes with concentration. For example, some political leaders or religious preachers deliver t heir speeches with prolonged pauses every few words or sentences. They may be using the pauses as a rhetorical device to emphasize their point. However, these pauses may instead break the listener’s attentiveness by letting him or her mentally wander away from the topic to thoughts about the speaker’s fluency or halting speech, or altogether unrelated issues such as what he or she ate for breakfast. In such situations, there may not be much a listener can do to remain attentive. However, if he or she keeps looking at the speaker with steadfast eyes, the mind’s tendency to wander could be significantly controlled.

- Paying attention to the speaker and not the speech: Many times listeners fail to listen properly because they are distracted by the speaker’s face or dress or manner of delivery, just as if a dancer is very beautiful, we may be distracted by his or her beauty and miss the beauty of the dance. Thus, it is important to pay attention to the speech and its contents rather than focus on external factors that are not relevant.

- Listening too closely: The purpose of listening is to get the full meaning of what is said. The speaker’s point is understood by looking for the central idea underlying individual words and non-verbal signs and signals. So when the listener tries not to miss a single word or detail of what the speaker is saying, he or she may get lost in the details and may miss the point.

Unequal Statuses

In organizations, there are formal and informal status levels that affect the effectiveness of face-to-face oral communication. A subordinate would generally listen more and speak less while interacting with his or her superior. The exchange of ideas is blocked by diffidence on the part of the subordinate because of the superior position of the speaker. Upward oral communication is not very frequent in organizations. Fear of the speaker’s superior status prevents free upward flow of information. This limits free and fair exchange of ideas.

The Halo Effect

The awe in which a speaker is held by the listener affects the act of listening. If the speaker is greatly trusted and held in high esteem as an honest person, his or her statements are readily taken as true. Oral communication is thus conditioned by the impressions of the listener about the eminence of the speaker. The listener’s impressions and not the intrinsic worth of the message determine the effectiveness of such communication. For instance, due to the halo effect, buyers may go by a trusted seller’s view rather than by their own judgment of a product’s quality.

Oral communication is conditioned by the impressions of the listener about the eminence of the speaker. The listener’s impressions and not the intrinsic worth of the message determine the effectiveness of such communication.

Complexes

Lack of confidence or a sense of superiority may prevent proper interaction between persons in different positions. Sometimes an individual may suffer from a sense of inferiority and therefore fail to take the initiative or involve himself or herself in conversation, dialogue, or other forms of oral communication. Similarly, some persons consider themselves too important to condescend to talk with others. Often, these are misplaced notions of self-worth, but they do block oral communication.

A Closed Mind

Listening, to a large extent, depends on one’s curiosity to know things. Some individuals believe that they know everything in a field or subject. Their minds refuse to receive information from other sources. In addition, some persons feel too satisfied with their way of doing things to change or even discuss new ideas. A closed state of mind acts as a barrier to oral communication, which demands a readiness and willingness on the part of the listener to enter into dialogue.

Listening, to a large extent, depends on one’s curiosity to know things.

Poor Retention

In dialogue or two-way oral communication, a logical sequence of thoughts is essential for successful communication. To speak coherently and comprehend completely, one has to understand the sequence of ideas. The structure of thoughts must be received and retained by the listener to understand arguments. The cues that signal the transition from one set of ideas to another must be retained by the listener to be able to grasp the full sense of the message. In case of poor retention, the listener fails to relate what he or she hears with what he or she had heard earlier. Moreover, if the listener fails to remember previous discussions, the whole conversation is likely to be lost in the absence of any written record.

The cues that signal the transition from one set of ideas to another must be retained by the listener to be able to grasp the full sense of the message. In case of poor retention, the listener fails to relate what he or he hears with what he or she had heard earlier.

Premature Evaluation and Hurried Conclusions

Listening patiently until the speaker completes his or her argument is necessary for correct interpretation of an oral message. The listener can distort the intended meaning by pre-judging the intentions of the speaker, inferring the final meaning of the message, or giving a different twist to the argument according to his or her own assumptions or by just picking out a few select shreds of information. These mental processes may act as a block to listening, affecting accurate exchange of information.

Abstracting

Abstracting is the mental process of evaluating thoughts in terms of the relative importance of ideas in the context of the total message. This is possible only by listening to the whole message. Abstracting acts as a barrier when a listener approaches a message from a particular point of view and focuses his or her attention on selected aspects of the conversation. This acts as a barrier to a full understanding of whatever is exchanged between two persons.

Slant

Slant is the biased presentation of a matter by the speaker. Instead of straight and honest communication, the speaker may adopt an oblique manner that could verge on telling a lie. When a matter is expressed with a particular slant, important aspects of the message are suppressed, left out, or only indirectly hinted at. Well-informed listeners usually do suspect the cover-up/slant. But uninformed listeners may accept the slanted message.

Cognitive Dissonance

At times listeners fail to accept or respond to assumptions deriving from new information as they may be unprepared to change the basis of their beliefs and knowledge. In such a discrepancy between a listener’s existing assumptions and the position communicated by the speaker, some listeners try to escape from the dissonance by reinterpreting, restructuring, or mentally ignoring the oral interchange. Cognitive dissonance interferes with the acceptance of new information. It may also lead to several interpretations of a new message or view. In the absence of cognitive dissonance, a listener has the skill, ability, and flexibility of rational thinking, promoting effective oral communication. For business executives, the skill to move from one mental frame to another is essential for efficient oral exchange of ideas, beliefs, and feelings.

Cognitive dissonance interferes with the acceptance of new information.

Language Barrier

The language of communication should be shared by the speaker and the listener. In business, English is widely used in most parts of the world. The ability to converse in English is essential for executives in a multi-lingual country like India. English is now the global medium for conducting business, and the lack of knowledge and practice of spoken English acts as a barrier to verbal communication.

The listener should also be familiar with the accent of the language in use, as a new accent can often be difficult to follow for those unfamiliar with it. For instance, in India, even those who speak English fluently need special training to work in call centres so that they can understand what overseas callers say over the phone. Workers involved in outsourced businesses tend to overcome their initial language barrier.

The effects of most of these barriers that interfere with the proper response to oral messages can be reduced or even removed through effective listening. In order to develop good listening skills, we must first identify and understand the characteristics of effective listening.

Besides the barriers in listening discussed in this section, there may be other factors that affect listening, as shown in Exhibit 6.2. For instance, many studies show that men listen mostly with the left side of the brain while women tend to use both sides. Further, studies also suggest that left-handed people may use a part of the brain to process language that differs from their right-handed counterparts. Such differences in brain dominance and lateralization could affect listening, either positively or negatively.

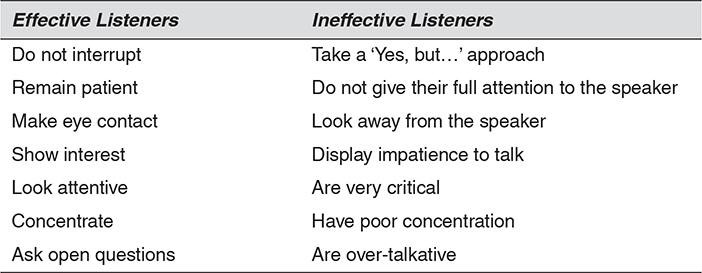

CHARACTERISTICS OF EFFECTIVE AND INEFFECTIVE LISTENERS

To improve our listening skills, we must know the characteristics of effective as well as ineffective listeners and identify our own weaknesses as listeners. Exhibit 6.3 contrasts the characteristics of effective and ineffective listeners.

Good listeners try to encourage the speaker by their body language and expression. They indicate interest and understanding regarding the subject of discussion. Poor listeners, on the other hand, annoy and disturb the speaker. They may have the habit of interrupting or showing little interest in what is being discussed. Unnecessary interjections such as ‘yes’, ‘but’, and ‘ifs’ should be avoided when they disturb the speaker.

After knowing how effective and ineffective listeners differ in their listening behaviour, try to recognize your own behaviour and attitude.

Exhibit 6.2

Differences in the Listening Process

Left-sided Listening in Men

Our brains are divided into four parts, and each part performs different functions and has different abilities. The right frontal part is best at creative tasks and ideas; the right basal part is responsible for feelings, intuition, compassion and interest for others. Logic and reasoning are governed by the left frontal part, which is responsible for abilities such as problem solving, strategic vision, leadership, and decision-making skills. The left basal part is best at organizing the world; sorting, arranging and filing; and keeping order and maintaining routine.

Each of us possesses the abilities governed by the four parts of the brain to some extent, but there are differences in how much we use each part. About 95 percent of us use some part of the brain more than others (only 5 percent of us use all the parts equally). Studies show that men tend to use more of the left part of their brain while women usually use more of the right.

Studies also suggest differences in listening in men and women. According to some research studies, men listen with only one side of their brains while women use both. Researchers have compared the brain scans of men and women and found that men mostly use the left side of their brains, the part long believed to control listening and understanding.

The question is: which is normal? Maybe the normal for men is different from the normal for women. Could this be the reason why men don’t like to listen to what doesn’t interest them, and listen repeatedly to something they like?

Listening in Left-handed People

Right-handed people are many more in number than left-handed people on earth. But, when it comes to processing language, a higher proportion of left-handed people process language effectively, as compared to right-handed people.

Normally, people use both sides of the brain to process language. The dominant hemisphere deals with articulation and calculation, and the non-dominant part is used for abstract thinking. According to the findings of the American Academy of Neurology in Philadelphia, the United States, left-handed people may use a (dominant) part of the brain to process language which differs from their right-handed counterparts. As a result, left-handed people could have different types of intelligence. For example, a person could be the CEO of an organization and yet not have good road sense.

Exhibit 6.3

Characteristics of Effective and Ineffective Listeners

GUIDELINES FOR IMPROVING LISTENING SKILLS

Effective communication is associated with the power of speaking well, but without good listening, successful communication is not possible. The spoken word fulfils its purpose only when it is carefully heard, understood, interpreted, and registered in the listener’s memory.

3

Know some guidelines for improving listening skills.

The effectiveness of communication is the function of both effective speaking and effective listening. To communicate successfully, the speaker’s words should be well articulated and, at the same time, they must be well received. The guidelines given here should be helpful in improving one’s listening skills.

When two people are talking simultaneously, neither can listen to the other. To have a successful dialogue, it is necessary that when one person wants to speak, the other person keeps quiet and listens. No one can talk and listen at the same time. In classrooms, it is common for teachers to ask students to stop talking to ensure that they are able to listen to the lecture. Similarly, the teacher stops talking when a student wants to say something.

- Speak less, listen more: The purpose of listening is to know what the speaker wants to say or to learn from the speaker. Listening is an act of cooperation in the sense that it takes advantage of others’ knowledge and experience. Therefore, devoting time to listening rather than speaking is in our self-interest.

- Do not be a sponge: It is not necessary to concentrate on every word of the speaker’s. Instead, it is more important to get the main point, theme, or central idea and concentrate on it. Minor details are not as important.

- Observe body language: Effective listeners do not pay attention only to what is being said, but also notice how it is said. They observe the feelings, attitudes, and emotional reactions of the speaker based on his or her body language.

- Focus on the speaker: Facing the speaker and making eye contact make the speaker feel that the listener is interested in what he or she is saying.

- Separate the ideas from the speaker: Good listeners do not allow themselves to be overly awed by the speaker’s status, fame, charm, or other physical and personal attributes. They separate the person from his or her ideas. Effective communicators are not conditioned by their personal impressions and prejudices, but are able to focus on the content of what is being spoken.

- Listen for what is left unsaid: Careful attention to what is not said, in addition to what is said, can tell the listener a lot about the speaker’s feelings and attitude towards the subject of discussion.

- Avoid becoming emotional: Good listeners remain calm and do not become emotionally charged or excited by the speaker’s words. Becoming too angry or excited makes it difficult for the listener to respond or express himself or herself objectively and rationally.

- Do not jump to hasty conclusions: Listeners should allow the speaker to conclude his or her point. Only then should they try to interpret and respond to it. Hasty inferences may not represent what the speaker intended to communicate.

- Empathize with the speaker: Effective listeners keep in mind the speaker’s point of view by focusing on the big picture, background constraints/limitations, and special needs and the emotional state of the speaker.

- Respect the speaker as a person: It is important to listen with respect for the other person. Do not allow the speaker to feel hurt, ignored, or insulted.

Exhibit 6.4

Effective Listening—Six Steps Away

Step1: Keep quiet—as much as possible.

Step 2: Don’t lead—unless you want to hear the opposite of what is being said.

Step 3: Don’t react defensively—if what you hear bothers you.

Step 4: Avoid clichés—to make meaningful statements.

Step 5: Remain neutral—no matter what you think of others.

Step 6: Resist giving advice—until asked for directly.

There may be nothing new in these guidelines. However, a reminder of the ways of improving listening, as illustrated in Exhibit 6.4, can be of great value for improving the effectiveness of communication.

RESPONSIVE LISTENING

Distortions in communication take place because of the nature of its three elements: the sender, the receiver, and the message. In earlier chapters, we have seen how messages get filtered and mixed with the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of both the sender and the receiver. Moreover, the message itself is subject to distortions resulting from the limitations of language as an adequate vehicle for communication.

4

Understand how to craft reflective and clarifying responses that demonstrate good listening skills.

Lynette Long, in her book Listening/Responding: Human Relations Training for Teachers2, questions the possibility of appropriate communication between the speaker and listener. She defines the communication process as one in which:

- What the speaker feels and what s/he means to say are not the same,

- What s/he means to say and what she/he actually says are different, and

- What s/he says and what the listener hears are also different. It’s a wonder, then, that what the speaker thinks is ever what the listener hears.3

However, Long suggests a course of training to enable a listener to respond to what the speaker thinks and not what the listener hears.

In light of their value for teachers, managers, and interpersonal communicators, Long’s two basic concepts of responses, basic reflective response and basic clarification response, are briefly discussed here.

Basic Reflective Response

Listening should be facilitative. The speaker should feel encouraged to speak out. He or she should feel that he or she has been heard and rightly understood. According to Long, the easiest way to show facilitative listening is reflection, ‘which requires that the listener accurately paraphrase the essence of the speaker’s message. This paraphrasing lets the speaker know that you have accurately heard him/her’. A reflective response should not, however, have any new information based on the listener’s own thoughts or views.

Listening should be facilitative. The speaker should feel encouraged to speak out.

As an example of a reflective response, consider the following example in which Manisha accurately paraphrases Abhinav’s thought:

Abhinav: I’m feeling so stupid. I expected it to be a most entertaining movie. The way you described it, I thought it would be a fun. But the whole thing makes no sense. Like most Indian movies, it’s just so lousy.

Manisha: The movie does not meet the expectations I had raised on the day of its release.

Manisha’s response rephrases the essential disappointment Abhinav expresses about the movie, and thus it makes him feel that he has been correctly heard and understood by her.

But suppose, Manisha responded as follows:

Yes, most Indian movies turn out to be boring.

Abhinav would have felt that Manisha missed what he wanted to convey—his disappointment. He was led to believe the movie was highly entertaining, but it turned out to be quite boring.

In crafting a reflective response, the listener responds only to what is presented by the speaker. For example, if only feelings are presented, the listener must respond to those feelings; if a cognitive matter is presented, he or she must respond to those components of the thought alone. The listener just repeats (mirrors/reflects) what the speaker communicates. He or she adds no new material while responding reflectively.

A message can have three component elements. The first is the experiential component, which answers the question, ‘What happened’? The second is the cognitive component, describing what the speaker thinks about what happened. These two components form the content of the message. The third component is the affective element of the message, which reveals how the speaker feels about what happened—this is more emotional than analytical. Most messages contain at least two of these three components. The listener must identify experiential, cognitive, and affective components and then decide which of these components to respond to. He or she also has to decide whether to respond with reflection or with some other listening technique.

As an example, let us break the following statement into its three component parts.

Ankit: Sometimes only luck saves us. Today, while driving to my office, I happened to get delayed, and, therefore, I reached the office parking lot just after the blast.

- The experiential component: What happened? While driving to his office, Ankit happened to get delayed and reached the parking place after the blast.

- Cognitive component: What is Ankit’s cognitive reaction to this happening? He explains what happened by attributing it to luck (‘Sometimes, only luck saves us’.).

- Affective component: How does Ankit feel about what happened? No feelings are explicitly expressed in his statement, but it is implied that Ankit feels lucky to have been delayed while driving to this office.

Here, I may point out that many of you may not agree with Ankit’s sentiment ‘sometimes, only luck saves us’. It is indeed hard to differentiate between thoughts and feelings. Many times, we use the expression ‘I feel’ to convey what we think about someone. For example, we might say ‘I feel he is a good person’. In fact, this is a thought, not a feeling that we are talking about.

We can now see that the listener should respond to all the components of the message: the experiential, the cognitive, and the affective. Of course, all the three parts may not always be present in a message. But whenever the affective component is present, the listener must respond reflectively to it because this part communicates the speaker’s feelings and is therefore most important from the speaker’s point of view.

Now, assuming yourself to be a listener, analyse the following conversation and try to respond reflectively to the speaker’s message.

Abhishekh: I mostly go out for an evening walk with Juhi, but this evening when I reached her house, she had already left. She knew that I was on my way to her place. She is really so inconsiderate.

To respond to Abhishekh, first break the statement into the following three components:

- What happened to Abhishekh?

- What does Abhishekh think about what happened?

- How does Abhishekh feel about what happened?

In your response, you may repeat the gist of the event, but you should reflect on the affective part by restating it completely. You can therefore respond by saying: ‘You were delayed on your way to her place, but Juhi should have waited for you’. Another possible response is: ‘You were late. But Juhi’s going out without you must really be so irritating’.

Basic Clarification Response

A clarifying response is more refined than a reflective response. The clarifying listener tries to understand the thoughts and feelings of the speaker by placing/projecting himself or herself in the speaker’s situation. Such a listener ‘assumes the internal frame of reference of the speaker’ according to Long. It is important to note that clarifying listeners do not identify their own experiences with the speaker’s. Instead, they focus and elaborate on the speaker’s thoughts and feelings.

The clarifying listener tries to understand the thoughts and feelings of the speaker by placing/projecting himself or herself in the speaker’s situation. Such a listener ‘assumes the internal frame of reference of the speaker’.

The reflective listener repeats the content of the message, whereas the clarifying listener ‘amplifies the stimulus statement’ by elaborating on the unstated thoughts and feelings underlying the speaker’s expression. Both what is said as well as what is left unsaid (but is implied by non-verbal body language) are together analysed to understand the finer workings of the speaker’s mind.

According to Long, clarifying listeners integrate verbal and non-verbal messages to gain a full understanding of the message and bring into focus and ‘attend to details of the communication that might otherwise go unnoticed’. In clarifying what the speaker has told them, they expand on both the feeling and content expressed by the speaker. Many times speakers may not be aware of the full meaning of their statements. Clarifying listeners help speakers better understand themselves.

A clarifying response responds to what is not said as well as what is said. Clarifying listeners amplify and elaborate on the comments of the speaker. They add deeper feeling and meaning to the expressions of the speaker by responding to his or her underlying thoughts and feelings.

Some of the words in this elaboration may need to be explained. Let us see how Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English defines these terms. Amplify means ‘to explain something that you have said by giving more information about it’. Elaborate means ‘to give more details or new information about something’. Clarify means ‘to make something clearer or easier to understand’.

Difference Between Clarifying Listeners and Interpretative Listeners

The focus of clarification is on the speaker. The listener is engaged in interpreting the speaker’s feelings and thoughts, which may remain incomplete or unexpressed. It should be noted that the clarifying listener adds no new information to the speaker’s statement. The listener’s comments expand—but do not interpret—what has been said. Clarification is done in terms of the speaker’s thoughts and feelings. It starts by referring to the speaker. For example, it could begin with phrases such as ‘It seems you…’ or ‘Perhaps you feel…’. The exercise of clarification is done with the purpose of helping the speaker understand his or her own feelings more fully.

According to Long, an interpretative listener on the other hand adds ‘new content and feelings to the expressions of the speaker—content and feelings that are not contained in the previous expressions of the speaker but are based on the listener’s projections concerning the speaker as a person’4. Interpretations are based on the listener’s knowledge of the speaker, on the ways human beings act in similar situations, or on the listener’s personal biases and opinions, with which the speaker may or may not agree. Incorrect interpretation shows lack of understanding on the part of the listener. To be helpful as a listener, one should first listen to what is said and not ask why it is said. The listener should develop the ability to clarify rather than interpret what others say to be able to respond successfully.

Consider the following example:

Divya: I do not like oral reports. May I submit a written report, instead?

Mr Chakrapani: I know speaking before the whole class is difficult. You feel nervous. It seems everyone is looking at you and you become self-conscious.

Mr Chakrapani responds to Divya in a clarifying way. He focuses on her and her feelings. He gives his response in terms of Divya. He projects himself in the situation and feels what she feels. He uses the phrase ‘You feel…’, which communicates empathy. Finally, he amplifies her dislike of oral reports by bringing in her feeling of nervousness in standing before the whole class. Of course, this amplification is based on what Mr Chakrapani assumes about Divya’s preference for a written report. And it may not be absolutely true. She may also be thinking that a written report could result in a better grade. One can be certain about the correctness of his clarification only when Divya nods ‘yes’ in response to Mr Chakrapani.

Now, here is an example of interpretive listening:

Divya: ‘I do not like oral reports. May I submit a written report, instead’?

Mr Chakrapani: ‘I know it’s easy to get a report written by a senior and submit it’.

Mr Chakrapani responds to Divya’s statement not in not in terms of what is said, but in terms of what he believes or knows about the practice of submitting reports. His listening is conditioned by his knowledge/information about student practices that Divya may not be aware of. In this case, the listener responds to what he assumes, not what he hears.

Recognizing Unexpressed Feelings and Thoughts

It is most important to understand the feelings in a message. Even the speaker may find it difficult to express his or her feelings properly and fully. The listener should help the speaker express his or her feelings more freely. This can be done by amplifying the speaker’s feelings, which may be implied and not openly expressed. By listening to verbal expressions and non-verbal clues, the clarifying listener can get an idea of the problem that is bothering the speaker. The listener puts together the clues provided by the speaker’s tone, choice of words, pace of speaking, and intonation pattern to sense the underlying feelings of the message. Non-verbal clues such as gestures, facial expressions, body movement, and eye contact and movement, in combination with verbal clues, affirm the unsaid feelings and thoughts of the speaker. The clarifying listener then conveys to the speaker that he or she has recognized the feelings and thoughts he or she has not openly shared. This encourages the speaker to open up and talk about suppressed feelings and thoughts.

To understand clarification further, let us analyse the expressed and implied feelings in the following statement:

Monica: Of late, I have started feeling very distant from my family. I am unable to talk with anyone. I do not know what has gone wrong. Even when I talk to my brother or sister, I feel as if I am talking to some unknown person.

Expressed feeling: Feeling of distance

Implied feelings: Loneliness, worry, and anxiety about the loss of family ties and closeness

Now analyse the following statement for the speaker’s expressed and implied thoughts:

Surbhi: I tried hard to become the Indian Idol. I thought as a singer I was as good as anyone else. But, in the finals when I heard the other contestants, I realized I could not make it.

Expressed thought: I thought as a singer I was as good as anyone else

Implied thought: I did not estimate my singing ability correctly

We have now discussed some of the characteristics that help a speaker express his or her thoughts and feelings freely. Broadly speaking, a good clarification response has the following characteristics:

- Encourages disclosures by the speaker

- Pays close attention to the speaker’s feelings

- Communicates understanding of expressed as well implied feelings and thoughts

- Helps the speaker understand his or her problem

To test your understanding, choose which of Meera’s responses to Nidhi is a clarifying response and give reasons for rejecting the other three responses.

Nidhi: I have lot of problems with my finance professor. She does not like me. Can you do something about this?

Meera:

- I do not know your finance professor

- You believe your finance professor dislikes you and you want me to do something to help.

- When I was getting my MBA, my marketing teacher hated me. I was always scared about my grade in marketing because of our personal relationship.

- You are worried about your relationship with your finance professor. You believe she does not like you. You fear you may not get a good grade in her course.

If you chose D as the clarifying response, you are correct. Here are the reasons for rejecting statements A, B, and C as clarifying responses. Response A does not reflect a deeper understanding of the problem of personal relationships in professional settings. Nor does it identify Nidhi’s fear of not getting a good grade. Instead, it seeks to know more about her professor. Response B just reflects the feelings of the original statement; it does not amplify them or help Meera understand her feelings better. Response C is an example of the listener identifying with the speaker’s experience. A clarifying response, however, should focus on Nidhi’s experience and her feelings about it. Response D, on the other hand, is a correct clarifying response. In this response, Meera focuses on Nidhi’s worries and concerns about her relationship with her professor and her grade in the course. Nidhi did not directly state these concerns, but Meera perceives them as fears hidden in Nidhi’s mind. The original statement talks only of the teacher’s dislike of Nidhi and asks for some help in this regard. Meera elaborates on this and helps Nidhi understand her worry more clearly. The speaker can get a lot of satisfaction and fulfillment from knowing that he or she has been heard, understood, and accepted by someone.

SUMMARY

- This chapter explains how listening means paying thoughtful attention to what someone is saying.

- Listening carefully is an important skill for managers, and the skills of thoughtful listening should be cultivated by managers.

- The listening process includes giving undivided attention to the speaker, hearing, understanding, and interpreting the words, evaluating non-verbal expressions, empathizing with the speaker, and conceptualizing.

- There are various factors that adversely affect listening: lack of concentration, unequal statuses of the speaker and listener, a halo effect or complex, a closed mind, poor retention, premature evaluation, abstracting, biases or slant, cognitive dissonance, and language barriers.

- Some guidelines for improving listening include speaking less and listening more, observing body language, and focusing on and empathizing with the speaker.

- There are two basic concepts of responses: the basic reflective response and the basic clarification response. A reflective response paraphrases the speaker’s words and lets the speaker know that the listener has accurately heard him or her. A clarifying response ‘assumes the internal frame of reference of the speaker’ and elaborates on the speaker’s thoughts to draw out the speaker’s unsaid thoughts and emotions.

CASE: TOO BUSY TO LISTEN?

There are times when teachers are too busy to listen to their students’ difficulties. Students find them preparing the next day’s lecture, correcting scripts, or discussing college problems with other teachers.

Geeta, a BBA student, finds herself approaching her program coordinator, who seldom encourages students to discuss their personal problems or any course-related questions or concerns. The teacher brushes her off saying she is too busy.

Geeta: Madam?

Ms Srivastava: Yes?

Geeta: Can I talk to you just for a minute? I need your help.

Ms Srivastava: Not now, Geeta. I am marking papers.

Geeta: Can I see you after my class, please?

Ms Srivastava: Not today. I have to attend the faculty meeting and then I have to prepare tomorrow’s lecture. And I also have to enter these marks in the grades sheet. Today, I am too busy. Why don’t you go to Rita madam?

Geeta: Madam, I had actually first gone to Rita madam. She also told me she was not free. She was very busy with the college’s Annual Day function preparations.

Ms Srivastava: Yes, Geeta, we all are very busy till the end of this month.

Questions to Answer

- Discuss the barriers to sympathetic listening as shown by the responses of the teacher to Geeta.

- What, according to you, is the real reason for the teacher’s inability to listen to Geeta? Are they really too busy to listen to students’ problems?

- ‘I am too busy’. What does this statement show about the nature of the responses of some teachers?

REVIEW YOUR LEARNING

- ‘Listening is hearing with thoughtful attention’. Discuss.

- What is the advantage of being a good listener for a business executive?

- Describe in detail the process of listening.

- Describe some internal factors that act as barriers to proper listening.

- ‘Premature evaluations and hurried conclusions distort listening’. Discuss.

- Describe some methods of improving the listening ability of a person.

- Explain how a reflective response facilitates listening.

- Bring out the difference between ‘clarifying’ listeners’ and ‘interpretative’ listeners.

- What do you understand by the term ‘responsive listening’?

REFLECT ON YOUR LEARNING

- Consider the reasons for one’s occasional lack of concentration on what is said.

- How would you evaluate yourself as a listener on the basis of the listening characteristics described in this chapter?

- In this chapter, there are some guidelines given for improving listening. Which of these would you find suitable for improving your listening?

- Do you believe that proper training can improve one’s listening skills?

- Do you agree with the view that it is not possible to have appropriate communication between a speaker and a listener?

APPLY YOUR LEARNING

Identify the nature of listening/responding given in the example below and give reasons for your choice:

Gaurav: I don’t believe I can complete this project report. I’m so frustrated. I have no background information.

Prasant: You feel discouraged because you feel you do not have the skills to write the project report.

Prasant’s response is:

- Interpretative

- Reflective

- Clarifying

- Responsive

SELF-CHECK YOUR LEARNING

From among the given options, choose the most appropriate answer:*

- Most of our waking time goes in:

- hearing

- speaking

- writing

- reading

- Listening, like speaking, reading, and writing, is:

- a skill

- a gift of nature

- an art

- a habit

- A serious listener concentrates on:

- the speaker’s physical appearance

- the speaker’s body language

- the message

- other thoughts

- As a sympathetic listener, you should consider the message from the point of view of:

- the audience

- yourself

- the speaker

- others

- When a listener abstracts partially, listening is:

- helped

- distorted

- obstructed

- slanted

- Good listeners concentrate on:

- the speaker’s main thought

- the speaker’s every word

- important words

- minor details

- A reflective listener:

- thinks about the speaker’s message

- appreciates the message

- ignores the details

- repeats the message’s essential parts

- A clarifying listener:

- explains the message

- repeats what is said

- illustrates the message with examples

- elaborates the speaker’s underlying thoughts and feelings

- Listening and hearing refer to:

- the same thing

- different things

- a specific act versus a general act

- mental and physical acts, respectively

- Listening, to a large extent, depends on a person’s:

- desire to know

- interest in others

- taste for gossip

- closed mind

ENDNOTES

- T. R. Vivek, ‘Strat Talk’, The Economic Times, 20 April 2007.

- Lynette Long, Listening/Responding: Human Relations Training for Teachers (California: Thomson Brooks, 1978), p. 16.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- Ibid., p. 88.