Chapter 13

Technical Tips and Habits of Mind

Read this when:

- You are a brand-new coach and want to address issues of scheduling and time management

- You suspect that your coaching conversations don't flow or don't get where you want them to get or feel awkward

Tricks of the Trade

The coaching tips and habits of mind in this chapter are shared as they arise sequentially in coaching. I'll begin with the logistics of setting up a coaching schedule, planning a coaching conversation, and preparing for a coaching meeting. Then I'll describe the arc of a coaching conversation, how to manage some of the technical elements during a conversation, and which habits of mind a coach may need to hold during a conversation. Finally, I'll suggest some routines for closing a coaching conversation.

Scheduling

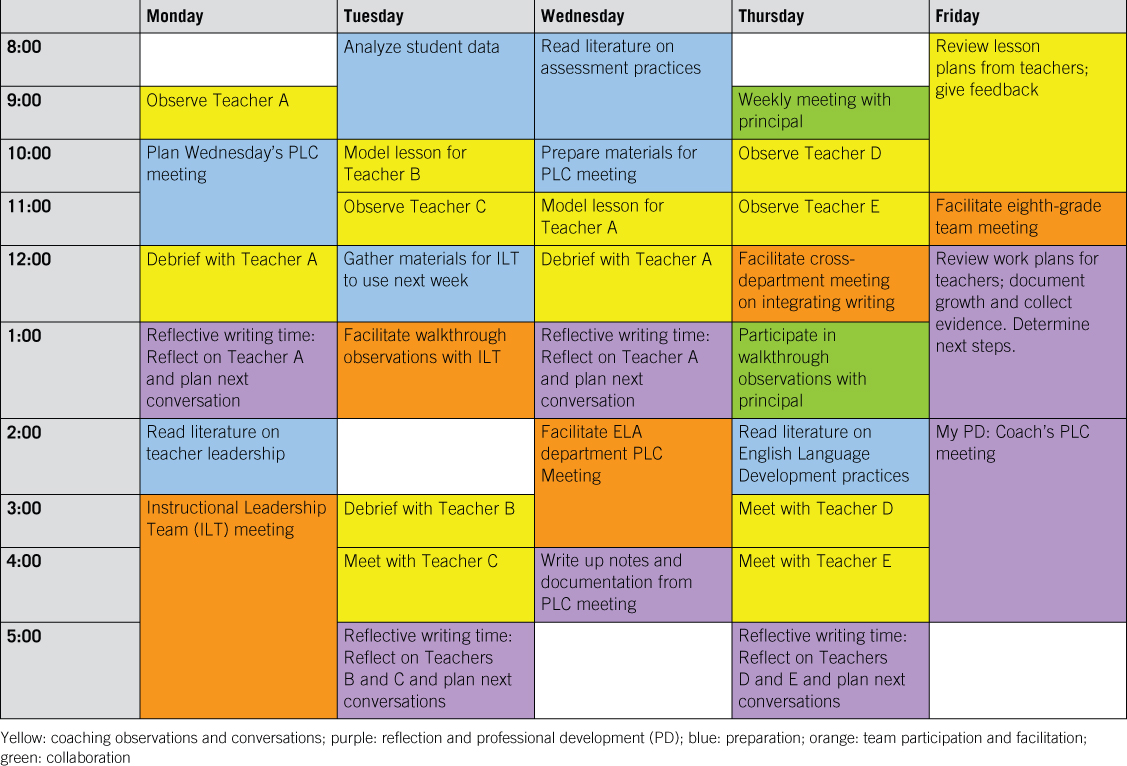

If a coach can construct his own schedule, (as opposed to being handed one) then he can consider how to use his time. This gives him the opportunity to manage his time well and also develop a valuable communication tool so that his supervisor and teachers know what he is doing and how he spends his days.

A coach may be most effective when his time is distributed amongst five task areas:

- Coaching observations and conversations.

- Preparation: gathering materials for clients, reading research and best practice, analyzing student data, planning meetings and coaching conversations, and so on.

- Collaboration: the meetings that a coach might have with a principal, another administrator, or a district partner, or participation in site walkthroughs or instructional rounds.

- Team participation or facilitation: Coaches may support teams at the sites they work at—maybe an English department, or a fourth grade circuit of teachers. If they are site-based, then coaches may also participate in leadership and decision-making teams.

- Coach reflection and professional development: It can be very useful for a coach to dedicate some time each day to reflection. Coaches should also be engaged in their own systematic professional development, ideally guided by a more experienced coach. Chapter Fifteen will expand on this.

Figure 13.1 offers a sample weekly schedule for a site-based coach. On my website there's an example of a centrally-based coach schedule. All coaches should develop a weekly schedule for their own focus and direction and for external accountability and communication purposes.

Figure 13.1 Sample Weekly Schedule for Site-Based Coach

Planning for a Coaching Conversation

Planning for a coaching conversation is similar in some ways to planning a lesson—we construct a couple clear goals, design a route to meet those goals, anticipate the challenges that might arise, and review material that might be helpful. As when you design a lesson, when you plan a coaching conversation keep in mind that you may need to change course, modify plans, or even abandon the directions and activities you planned because some other skill gap becomes apparent or a more pressing need presents itself.

Planning for a coaching session is essential. After some experience, we might be able to walk into a meeting with a client and wing it but we will be much more effective if we have a plan tucked into our coach-minds. As we move through the conversation the client won't notice when we subtly guide the conversation, the thoughtful questions we seem to pose on the spur of the moment, or the way we calmly react to whatever comes up. If we have planned, then we might have anticipated that the client could need a particular resource and we'll have a copy of that resource copied and ready to hand over. If we have planned, then we walk into the coaching meeting with the big picture fresh in our minds—the needs of the client and his goals, as well as the needs of the students and community he serves.

So how do we plan this meeting?

Step 1: Where Does My Client Need to Go?

The first step to plan a coaching conversation is to identify where my client needs to go in a particular session. To do this, I read over the notes and reflections I made after our last meeting. This helps me remember where my client was in her learning the last time we met. Then I consider where the conversation might need to go to move the client toward her goals. In order to do this, I review the work plan and my notes from recent sessions. I consider the evidence that my client is making progress and speculate on remaining gaps in skill, will, knowledge, or capacity. I look through my notes to see if there are any patterns in the holes—are there topics or issues that the client seems reluctant to address?

Based on the client's goals and recent sessions, I plan for the upcoming meeting. What might be a meaningful outcome for this meeting? What might be helpful for my client to think about or do? Which coaching approach might be the most effective? Might it help to engage in some action together? Or have we been doing a lot of activities but not spending enough time reflecting on them? Exhibit 13.1 offers a template for a planning coaching conversation.

Step 2: Who Do I Need to Be?

Once I have determined where the client needs the conversation to go, and I have some ideas about how we can get there, then I figure out who I need to be as a coach. This is the second step in planning a coaching conversation.

I know my clients need me to be grounded and present when I walk into their rooms. Simply by conveying a sense of calm a reflective space is opened that invites others to slow down and learn. I consciously, regularly cultivate a grounded state of being. There are many ways to do this. Some are daily habits such as getting exercise, prioritizing eight hours of sleep, and eating nutritious food. I encourage coaches to consider how they attend to their own emotional, physical, social, and spiritual needs—doing so will definitely improve a coach's skills.

I also have a set of practices which I engage in right before a coaching session. First I take stock of my own mood—am I feeling tired? Agitated? Worried? And what kind of disposition might my client need me to be in? And then I work to make any shifts that might help. I often listen to music while driving to a meeting—music always transforms my mood. I rarely go into a coaching session without spending at least five minutes, almost always in my car, quietly breathing. I schedule this in my day—I arrive early, turn off the music, close my eyes, and breathe. Those five minutes are critical to the effectiveness of my work.

Some of the other strategies I use to become calm and grounded are the following:

- A quick, fast walk

- Yoga stretches

- A journal write where I get out all the thoughts that might distract me

- Saying mantras or affirmations such as, “I am focused and calm,” “I can hold a space for learning,” “Everything is OK.”

- Talking with a trusted coach-colleague to clear my mind if anything work-related is clogging it.

I've discovered that even if it means I'll be late, I can't go in to a meeting without taking time to get grounded—five minutes is usually enough and makes all the difference in the subsequent hour. When my client greets me and asks, “How are you?” I need to be able to smile and honestly respond, “I'm good.”

Getting grounded is essential, but it's not the only preparation a coach can do. I know that for a client to be receptive to coaching, I need to be nonjudgmental—and I am not always in that frame of mind; before a meeting, I often activate my compassion for a client. Sometimes I visualize that I am the teacher or principal I'm about to meet with; I imagine what his day has been like—what he's seen, done, heard, felt, wondered, feared, and needed. I recall his core values, vision, and commitment to students—all things that inspire me and make me believe in his potential. I remind myself of how grateful I am to have this client's trust and how privileged I am to be a witness to his growth and development. I can't take this for granted. This visualization often helps me transition into a more compassionate stance as I enter a meeting.

Sometimes if I'm particularly plagued by judgmental thoughts about a client, I visualize taking all my feelings and putting them into a big box. I put the lid on, and tell myself that after the meeting, if I want, I can open the box and reclaim them. Of course, sometimes they sneak out of the box during a coaching session, or sometimes a judgment surfaces that I forgot to stuff away. But before I go into a coaching meeting, I scan my mind for any thoughts that might not help us reach our goals for that day and then I clear them out of the way. Most of the time, I am more committed to being a good coach and transforming schools than to letting my judgments run wild.

When I knock on a client's classroom or office, I know that a large part of what will make the meeting successful is my disposition: If I'm confident, compassionate, grounded, and present, I know I can create a learning space for someone to explore his beliefs, behavior, and being.

The Arc of a Coaching Conversation

Effective coaching conversations have a structure. A coach needs to be aware of these and of the arc and flow of a conversation. Sometimes it can also help to make these elements explicit to a client.

A coaching conversation usually starts with a general check-in—the informal chatting or settling into a meeting. Although this dialogue should be limited so that we can get to our coaching work, we also look for opportunities to make personal connections with our clients. Asking a question such as, “How was your weekend?” is an invitation to raise topics outside of the work sphere. These brief conversations can help build and establish trust; they can also help us get a pulse on what's going on with our client outside of work (which, of course, can affect their work).

However, I am very cautious about revealing personal information. I do share, otherwise this chatty conversation would feel strange and one-sided, and, of course, sometimes clients ask questions. But I am very selective—I never want a client to be concerned with my emotional state. I also don't want to offer information that might raise any emotions or conflicts of interest for my client. Before I share anything personal, I think through how my client might hear, experience or interpret my story. How could it affect the way she thinks about me? About herself? If I have any question or doubt about how a client would hear a piece of personal information, I don't share.

Sometimes it's useful to make an agreement about how long you'll spend on a check-in, especially if working with a client who enjoys, or gets stuck in, the informal chatting phase of a coaching conversation. In addition, if the points raised in the check-in were weighty, we might ask for permission to set them aside for the duration of the conversation. We can also ask if there's anything the client needs to release so that he can engage in coaching. This can sound like, “Is there anything you'd like to put aside so that you can be present for our conversation?” Or, “Is there anything you need to do or share in order to be present without distraction?”

Once it feels like there's been enough warming up and checking in, it's the coach's responsibility to shift the conversation. We might say, “So, what's on your mind today? What would you like to talk about?” and jot down the topics that come up.

Another routine to begin a coaching conversation is to return to what was discussed at the last meeting. At the end of each coaching session, the client will usually have some follow-up actions to take. It is important that the coach return to these to gently hold the client accountable for what she says she is going to do. If we miss this step, we can undermine our credibility. We can open this conversation by saying, “Last week you decided you wanted to try … How did those things go?” or “Last week you committed to … What happened?” Depending on what the client says, this may constitute the entire coaching conversation—either because we continue to reflect on what happened or we move into next steps.

After checking in, creating a plan for the conversation, and returning to the previous week's commitments, the coach moves the discussion into the agreed-on topics for the meeting. Now the coach engages in the various approaches and strategies discussed in Chapters Eight through Twelve and moves through listening, questioning, and learning activities.

Let's take a look at a couple more elements from the coaching conversation before exploring how a session can wrap up.

Logistics during a Conversation

When we engage our client in creating a plan for the conversation, we want to be clear about how much time we have together and make agreements about how to use it. Often, I've found that clients name a list of topics to discuss that will exceed the time we have. I help prioritize the list and create time frames for how long to spend on each item. Usually, when we're prioritizing the list, I'm conscious of the plan I made for the meeting and what I suspect could help the client move forward on her goals. If so, I suggest we start with a particular item or I add a topic or an activity to the list.

During the conversation, I agree to keep track of time. I set the timer on my phone and tuck it out of sight so that we're not distracted by it. I also make sure that we'll have a few moments to reflect on today's work and determine next steps. Frequently, conversations become so engrossing that the end is cut short. It's the coach's responsibility to calmly wrap up a meeting so that the client can feel a sense of closure and be clear on next steps.

The other responsibility a coach has during a meeting is to document the conversation. I take notes for several reasons: first, so that I'll remember things. Sometimes I also jot down words or phrases a client says that I might want to return to. Second, I feel it is my responsibility to notice and document the client's changes in practice, developing beliefs, and shifts in ways of being. I'm always listening for indicators of growth in those areas and at different times I'll share what I've recorded. I often compile what I've heard and e-mail a summary to clients after our meetings. I also need this kind of documentation for the progress reports I write for supervisors and for my own reflection. Finally, I need notes so that I can plan our subsequent coaching session. Exhibit 13.2 offers a basic template to take notes on. There's an example of this kind of documentation on my website at www.elenaaguilar.com.

Technical Tips on Note Taking

I prefer taking notes by hand, in a notebook. I like a different colored spiral-bound notebook for each client. When I'm meeting with someone, I'm acutely aware of my body language; having a computer between us feels intrusive and blocks my line of view. Since I want to minimize every possible distraction, pen and paper are my preferred tools.

Another technical note: When I first started coaching, and hadn't yet internalized the kinds of questions that I wanted to ask in a coaching session, I kept a list of questions that I'd printed on cardstock tucked into my notebook. When I got stuck and couldn't remember how to phrase a confrontational question, for example, I subtly flipped the pages of my notebook and glanced at my list.

I staple my work plan to the inside cover of my notebook. I don't always remember the entire plan and sometimes I reference it. I also paperclip my plan for a coaching conversation to my notebook—usually on the page preceding the blank one I intend to write on during a meeting. I'll review it if I need during a conversation. Don't worry about clients noticing when you use your resources—there's nothing wrong with being transparent about our practice. Letting clients know that you planned and thought carefully about how to support their learning can build trust and confidence in your competence.

Coach Responsibility during Conversation

During a coaching session, the coach is responsible for guiding the conversation, keeping the client's history and goals in mind, listening deeply, using various questioning strategies to advance the client's thinking, looking through a set of lenses in order to have multiple perspectives on the situation, offering activities that can deepen learning, managing the time and taking notes, and finally, the coach is responsible for monitoring her own mental and emotional processes in order to be able to do all of this. This is the art of transformational coaching.

When we come into contact with the other person, our thoughts and actions should express our mind of compassion, even if that person says and does things that are not easy to accept.

Thich Nhat Hanh (2012)

In order to ensure that our client is fully engaged in the learning space we're holding, we need to pay close attention to our client's verbal and nonverbal cues. We want to be particularly attuned to any indicators that our client is experiencing distress. If for example, a client gets restless and finds several excuses to get up and move about, something might be going on. When we notice behaviors that might indicate the client is upset, it can be useful to ask about what's going on. For example, you can simply say, “What's coming up for you right now?” Invite the client to notice and reflect on her emotions—and then adjust your coaching approach. Sometimes we may also notice physical cues such as smiles, unfurrowing brows, dropping shoulders, or deep exhales that let us know that we're on the right track—these changes in body language are good data points that our coaching is effective.

We also want to notice when a client uses language that may reflect emotional distress. If a client engages in “Yes, but …” dialogue with us or debates everything we say, he may be shutting down to the conversation. If we're not sure what's going on—we might observe cues that indicate distress or disconnect—it's always useful to ask. We can simply say, “Is this helping?” or “Can I check in on what's going on for you—I want to be helpful but I'm having a hard time reading how you're receiving this?” A client may take up this offer, and may have the emotional intelligence skills to name what he's experiencing, but he may not. It can be helpful to support the client by asking questions such as, “Can we explore some of the emotions that might be coming up? What part of your body are you feeling distress in? Can you describe it?” We also want to be cautious that we don't make our client feel more uncomfortable by naming the emotional discomfort that we observe. This is tricky, but necessary, terrain to negotiate on the journey to transforming behaviors, beliefs, and being.

Maybe you're reading this thinking, “I'm a math coach. I am assigned to help eighth-grade teachers improve their algebra instruction and conduct accurate assessments. Do I really have to deal with all of this emotional stuff? Can't we just talk about instruction?”

The answer, unfortunately, is no. Adults, just like children, cannot learn when their anxiety levels are high. Coaches must develop skills to address emotions and support our clients in managing them. Although some coaches are effective at supporting teachers in implementing a new curriculum or improving classroom management skills, coaches can be exponentially more powerful and effective when they also respond to the emotions that arise in teaching. Education is a deeply emotional arena for just about everyone who enters it—the beauty of coaching is that we are uniquely positioned to help these be positive emotional experiences where healing and transformation are possible.

Closing the Conversation

The way a coaching conversation wraps up is critical. We hope our sessions facilitate learning, push a client's thinking, open up emotional spaces, and provoke reflection and growth. We need to know, at the end of a meeting, if the client felt inspired, empowered, clear about his next steps, and confident that he can take them.

Sometimes a client offers unsolicited feedback by saying something like, “This was helpful,” or “I feel better.” If a client makes comments like these, a coach can ask for clarity or more details—both for herself as feedback and to push the client's reflection. You can say, “Would you mind sharing what exactly was helpful in today's session? I want to make sure I can do that again.” If a client doesn't volunteer feedback, then you can pose questions such as the following:

- How do you feel about our meeting today?

- What has been valuable in this session?

- What else might be helpful for me to do?

- What would you like more of or less of in our coaching work?

If the client's response is vague, that's OK. Ask follow-up questions if it feels like the client is receptive to giving you feedback, otherwise, let it go. You also don't want your client to feel pressured to praise you or say the time was helpful if it wasn't.

The second essential element to close a coaching conversation is to identify next steps. It's critical that our clients come out of a coaching session ready to take some actions. The end of a coaching session should always include a review of what the client is going to do next, when it will be done by, and anything the coach is going to do to support these next steps. For example, the coach might say, “I'm going to send you the notes I took by 8 a.m. tomorrow. I'm also going to find another sixth-grade math teacher you can observe. I'll do that by Monday. Let's go over your next steps, OK?” You might also close the meeting by agreeing on how you will check in with your client and see that he's doing what he said he'd do. For example, “So, you've determined that by Wednesday you're going to convene your leadership team for a meeting. I'm going to e-mail you on Monday to check in on how this is going.” Many clients want and appreciate this kind of gentle accountability.

Conclusion

Start measuring your work by the optimism and self-sufficiency you leave behind.

Peter Block (2011)

Peter Block's suggestion has become almost my singular aspiration in a coaching conversation—it's my main indicator of whether I did a good job. After a coaching meeting, the first thing I ask myself is whether I think my client is feeling more optimistic about what he can do. Does he feel more empowered? Did he reconnect with his vision, values, and abilities? This is sometimes a hard road to chart—optimism and self-sufficiency are challenging outcomes in our schools—and sometimes the journey is rough and painful. I don't always reach this end but I'm always aiming for it—and when I hit it, and I know I've reached it, it's been a good day of coaching.