Chapter 2

What Is Coaching?

Read this when:

- You're beginning a new coaching assignment; a clear definition will help you articulate your role and responsibilities, which in turn helps build trusting relationships

- You're a principal considering hiring a coach or establishing a coaching program

- You're looking for a coaching job and you want to find the best fit

A Story about a Coach Who Didn't Know What She Was

“What does she do?” they whispered behind my back during my first months as an English language arts coach.

“Are you here to help us with Holt?” Ms. X asked me in the hallway. When I said no, that I wasn't there to enforce usage of the mandated curriculum, and that in fact I didn't like textbooks (a statement that I hoped would earn me points—who likes curriculum police?), she threw up her hands and turned away, shaking her head.

The requests came: “Can you make some copies for me, put up a bulletin board, order books?” “Can you cover my class while I go to the bathroom?” “Can you find out why Dominique's mom won't return my calls?” “Can you get the principal to do something about these kids?”

I met some of these requests. And then I tried to observe a few English teachers, model lessons, compile student data, and facilitate the English department's meetings. I designed and delivered some professional development (PD) sessions. But most of my efforts were met with resistance. I struggled to build trusting relationships, I didn't see changes in teacher practice, and I felt ineffective and frustrated most of the time.

At first I wanted to blame the principal; he hadn't positioned me well, he hadn't defined my role, and he had thrown me into the most toxic department in a dysfunctional school. But it wasn't his fault—he was a new leader in a very difficult situation. And the school needed way more than a coach to solve its problems. It wasn't my fault that I was ineffective, either—I had good intentions and I knew a few things about instruction—but I had no training as a coach. I didn't know what to do or how to do it.

Unfortunately, I know that my experience at this school was not unique. The majority of coaches I have met say that they feel that their job description is not clear. A coach's need to have a sense of the field of coaching and then define her own work is an essential starting place. This chapter puts forth some definitions of coaching and the model described in this book—transformational coaching. After becoming familiar with coaching models, I suggest that coaches construct a vision for themselves as a coach.

Why We Need a Definition

The title coach has been loosely and widely applied in the field of education. New teachers are sometimes appointed a coach who might be a mentor and confidant, or simply someone who stops in every other week to fill out paperwork. Many mandated curricula initiatives deploy “coaches” to enforce implementation. Some schools have “data coaches” who gather and analyze data, prepare reports, meet with teachers to discuss the results, and suggest actions to take. Some districts assign coaches to underperforming veteran teachers as a step in the complicated process of firing a teacher. Central office administrators have also appointed “school improvement coaches” to schools that have failed to improve test scores. Finally, some teachers have experienced a coach who coplans lessons, observes instruction and offers feedback, models instructional strategies, gathers resources, and offers support with new curricula. There have been enough coaches passing through schools in recent decades that most educators have some idea about what a coach does. Coaches have a responsibility to understand this context and to provide a definition for what their work entails.

A definition of coaching is also necessary to help us come to agreement about what coaching is not. Let me suggest a few things that coaching must never be used for:

- Coaching is not a way to enforce a program. Coaches should never be used as enforcers, reporters, or evaluators. This approach has many negative implications and demeans the field of coaching.

- Coaching is not a tool for fixing people. It is not something you should do with or to ineffective teachers. It is not a box to be checked so that a district can move toward disciplinary measures. Coaching should not be mandated, and teachers or principals should be able to opt out of coaching. Coaching (as a form of professional development) won't be effective if the client doesn't want to engage in it. We can't force people to learn.

- Coaching is not therapy. A coach does not pursue in-depth explorations of someone's psyche, childhood, or emotional issues. While these areas may arise in coaching—and, in fact, they frequently do—the role of a coach is not to dwell here. Sometimes a coach needs to delineate the lines between what she knows and can do and what a mental health expert knows and can do for a client. A coach needs to be very clear about the boundaries between coaching and therapy, and to remember that the focus of coaching is on learning and developing new skills and capacities.

- Coaching is not consulting. A coach is not necessarily an expert who trains others in a way of doing something; a coach helps build the capacity of others by facilitating their learning.

Because coaching has been linked to enforcement of a program or disciplinary measures, and as such has disempowered educators, those of us who intend to practice it as a vehicle for transformation must be responsible for presenting a clear definition of what it is, who we are, what we do, and why we do it. We need to interrupt any stories that are not in alignment with what we're doing. Entering into a school or a coaching relationship with a clear definition that you can communicate will enable you to build much stronger relationships from the beginning.

Because there are so many different ideas circulating about what a coach is, when you start working with a new client it's important to ask him about his past experiences with coaching (even if your own definition of the role is clear). You need to know what he thinks the role entails, how he defines coaching, and what he wants and expects from coaching. See Chapter Five for more questions to ask in an initial meeting with a new client.

What Are the Different Coaching Models?

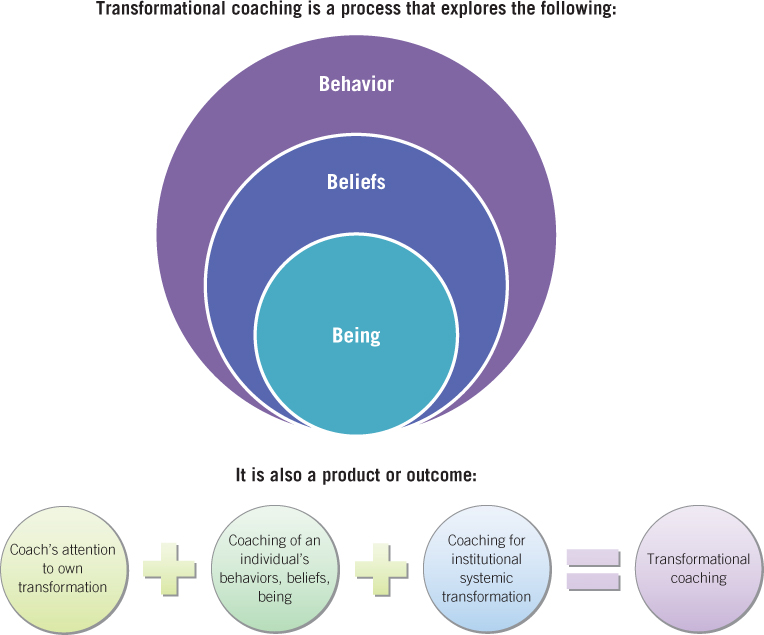

New coaches tend to focus on the actions, behaviors, and outward indicators of coaching, such as questioning techniques, observations, and giving feedback—the doing of coaching. Below the surface of what we do is what we think and believe about what we're doing. Finally, below that layer of beliefs and thinking is a layer of being—who we're being when we're coaching. The art of coaching is doing, thinking, and being: doing a set of actions, holding a set of beliefs, and being in a way that results in those actions leading to change. These are the three things that can make coaching transformational.

Let's first consider coaching models through two lenses: those that support only teachers and leaders in changing their behaviors, and those that support teachers and leaders in also considering changing their beliefs and ways of being. Directive coaching, which is also sometimes called instructive coaching, generally focuses on changing behaviors. When a coach suggests that a teacher circulate around the classroom while students are responding to a discussion prompt, her coaching is directive. Facilitative coaching can build on changes in behavior to support someone in developing ways of being or it can explore beliefs in order to change behaviors. When a coach asks a teacher to explain her decision making behind the delivery of a lesson, her coaching is facilitative. Finally, I'll describe transformational coaching, the model that I'm putting forth in this book and that I believe offers the greatest possibility for transforming our education system.

Coaches are much more effective when they can name the approach they're taking at a particular time. Having that awareness allows us to make decisions and take actions that are aligned to a specific model. We can also determine when shifting into a different approach might be more effective.

Directive (or Instructive) Coaching

Directive (or instructive) coaching (the terms are used interchangeably in the literature) generally focuses on changing a client's behaviors. The coach shows up as an expert in a content or strategy and shares her expertise. She might provide resources, make suggestions, model lessons, and teach someone how to do something.

This kind of coaching is frequently practiced by those who coach in a particular content, discipline, or instructional framework. For example, a district may adopt a new curriculum and provide coaches who will help teachers master the material. Or a school may take on a behavior management program and hire coaches who can support implementation. As the United States transitions to the Common Core State Standards, I anticipate many schools will hire coaches to support teachers in putting these standards into practice. In this model, the coach is seen as an expert who is responsible for teaching a set of skills or sharing a body of knowledge.

Directive coaching strategies are relevant and necessary at times, as in the case Tania at the beginning of her first year of teaching. However, these strategies are also limited. Directive coaching alone is less likely to result in long-term changes of practice or internalization of learning. A coach may notice that she returns to visit a teacher she worked with, only to find that the teacher has given up using the strategies that she appeared to have adopted in coaching. “What happened?” the coach might bemoan.

Such a scenario is often seen when a coach limits her coaching tools to directive strategies; the coaching did not expand the teacher's internal capacity to reflect, make decisions, or explore her ways of being. What was accomplished was a change in practice, for a limited time. For coaching to have deep, long lasting impact, it is imperative that a coach uses additional coaching strategies that support educators to explore, develop, and/or change their beliefs and ways of being.

Facilitative Coaching

Facilitative coaching supports clients to learn new ways of thinking and being through reflection, analysis, observation, and experimentation; this awareness influences their behaviors. The coach does not share expert knowledge; she works to build on the client's existing skills, knowledge, and beliefs and helps the client to construct new skills, knowledge, and beliefs that will form the basis for future actions.

An essential concept in many coaching models, including facilitative coaching, is the zone of proximal development (ZPD), which was developed by the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky. The ZPD is the difference between what a learner can do without help and what he can do with help. It is the range of abilities that one can perform with assistance, but cannot yet perform independently. When a learner is in the ZPD, if he is provided with appropriate assistance and tools—the scaffolding—then he can accomplish the skill. Eventually the scaffolding can be removed and the learner can complete the task independently. A learner's ZPD, therefore, is constantly shifting; the teacher or coach needs to have an acute understanding of it. Scaffolded instruction is also known as the gradual release of responsibility.

Coaching is the art of creating an environment, through conversation and a way of being, that facilitates the process by which a person can move toward desired goals in a fulfilling manner.

Tim Gallwey (2000, p. 177)

A number of coaching models lie within the broad domain of facilitative coaching. Cognitive coaching is a foundation for facilitative coaching because it addresses our ways of thinking and aims to build metacognition. It focuses on exploring and changing the way we think, in order to change the way we behave. Cognitive coaches encourage reflective practices and guide clients to self-directed learning.

Ontological coaching has also deeply influenced facilitative coaching. It emerges from the philosophical study of being and focuses on how our way of being manifests in language, body, and emotions. Our perceptions and attitudes are seen as the underlying driver of behavior and communication, and coaching focuses on exploring these. Resources for learning more about these coaching models can be found in Appendix E.

Transformational Coaching

Transformational coaching, the model that I'm putting forth, has not been widely used in schools. It draws from ontology, the philosophical study of being, from Robert Hargrove, the author of Masterful Coaching and a pioneer in using transformational coaching in the business world, from the work of Peter Senge and the field of systems thinking, and from Margaret Wheatley's writing and teachings. Transformational coaching incorporates strategies from directive and facilitative coaching, as well as cognitive and ontological coaching; what makes it distinct is the scope that it attempts to affect and the processes used.

Transformational coaching is directed at three domains and intends to affect all three areas:

- The individual client and his behaviors, beliefs, and being

- The institutions and systems (departments, teams, and schools) in which the client works—and the people who work within those systems (students, teachers, and administrators)

- The broader educational and social systems in which we live

A transformational coach works to surface the connections between these three domains, to leverage change between them, and to intentionally direct our efforts so that the impact we have on an individual will reverberate on other levels. Transformational coaching is deeply grounded in systems thinking. Systems thinking is a conceptual framework for seeing interrelationships and patterns of change rather than isolated events. Systems thinking helps us identify the structures that underlie complex situations and discern high- and low-leverage changes. By seeing wholes, we are much more effective in working toward transformation (Senge, 1990).

Coaching Behaviors, Beliefs, and Being

Changing behaviors is the goal in many forms of coaching. Exploring beliefs is also incorporated into some coaching approaches. But what does it mean to change your way of being? What does it mean to coach people on how they are “being”?

For a couple years, I coached a high school math teacher who played several leadership roles in her school. Her instructional practices were exceptional, and her beliefs about children contributed to equitable outcomes: she believed all kids could learn algebra—girls, boys, newly arrived immigrants, and so on—and they did. However, when she met with her colleagues for collaboration time or the school's leadership team, she often felt frustrated and impatient. She didn't feel she could communicate in the way she wanted to, she didn't feel understood, and she didn't get the results she wanted. Her verbal and nonverbal communication betrayed these feelings: her colleagues made comments such as, “What's up with Rachel today? She seemed really annoyed or something.” Or “I'm nervous about saying what I really think because Rachel is so smart and sometimes I feel like she dismisses my ideas even before they're out of my mouth.”

As Rachel began to recognize the effect she was having on her colleagues, and as she acknowledged that this would limit her effectiveness as a leader, she asked that my coaching address this. We worked on changing the specific behaviors that she was demonstrating, on exploring the underlying beliefs and thoughts, and we worked on who Rachel was “being” when she showed up at meetings in this way.

“Who do you want to be?” I prodded over and over.

“Someone who listens to others, who respects their perspectives,” she said. “Empathetic and compassionate, but I also want to push people in their practice.”

I helped Rachel develop a vision for herself as a teacher-leader, I helped her align behaviors and beliefs to this vision, and I gathered and shared data about how she showed up in different contexts. “Here's a transcript of what you said at your last math meeting,” I shared. “Which statements reflect your core values and the leader you aspire to be?”

At the end of our coaching work together, Rachel commented: “I feel like your coaching changed me from the inside out. I feel different way down deep inside of me and I see the impact of coaching in other areas of my life.”

Transformational coaching directly and intentionally attends to ways of being. We explore language, nonverbal communication, and emotions, and how these affect relationships, performance, and results. As transformational coaches in schools, we explore how our clients' ways of being shift depending on their contexts. Shifting is natural as we move into different settings, but sometimes we shift into ways of being that are not aligned to our vision for ourselves. For example, a principal may be able to “be” a certain way when he's leading teachers that come from his cultural background and demographic; however, when he works with teachers who are different, his way of being can shift. A transformational coach helps a client look at these shifts and explore the effects.

In order to transform our schools, we'll need to improve the craft of instruction and leadership and support educators to manage the physical, emotional, social, and intellectual demands of working in very diverse schools in a constantly changing environment.

Coaching for Institutional and Systems Change

A transformational coach thinks in terms of systems, helps a client see systems, and directs her efforts at the levels of an individual and the systems in which we are embedded. When we think in terms of systems, we are always looking for the links between the discrete problems that are presented and broader systems that exist now or that may need to be created: between the new teacher who is struggling with classroom management and the school and district's systems for on-boarding new teachers; between the principal who is frustrated by his staff's lack of compliance with e-mail protocols and the school's formal and informal communication systems. If we truly believe that everything is connected, in time and space, then without surfacing and addressing these connections the solutions that we come up with may not have the greatest impact. We explore systems in order to identify high-leverage entry points that could result in transformational changes for children.

What does this sound like in coaching? Here's a snippet of a conversation in which the coach is working from a systems-thinking perspective:

“I'm so frustrated,” says the teacher. “I only have about 40 percent of students turning in homework. What should I do?”

“What do you think is going on?” asks the coach.

“They're lazy. I want to institute detention for those who don't do it.”

“Let's hold off for a few minutes on a solution and consider why this is happening. OK?” The teacher nods. “So what might be the reasons they aren't doing homework?”

The reasons included these: students didn't understand the assignments, there were no consequences for not doing homework, they didn't remember what the homework was once they got home, many students didn't have quiet places in which to do homework in the evenings, many students worked after school or had responsibilities at home, students lost the assignments or didn't bring backpacks, and so on. The initial problem identified by the client was a symptom of much larger, complex problems.

As a systems thinker, the coach's first role is to carve out the time and psychological space for the client to explore root causes. We guide our clients toward an awareness of the systems that are interrelated to our problems, and then we seek high-leverage areas in which to take action. Let's consider what this might sound like in conversation with the teacher who is frustrated by the lack of homework submitted.

“We've surfaced a number of reasons that might contribute to students not doing homework,” says the coach. “Which of these are immediately within your sphere of influence?”

The teacher identifies several obvious areas. “Can you think of some that might be within your school's sphere of influence and might be something you could take to the leadership team to discuss?”

“For years we've talked about starting an after-school homework club,” says the teacher. “I'd like to push for that.”

“That sounds like a schoolwide support structure that could be developed—a systemic response to this dilemma. What other reasons might indicate a system response?”

“I think kids not remembering their homework might be about communication—how we communicate homework. They have six classes per day, and each teacher has a different process for telling kids what their homework is. I can see how it would be confusing,” says the teacher.

“That's a great observation. You could even take that to the next tenth-grade team meeting and discuss it.”

When a transformational coach works from a systems-thinking approach, many conversations will begin at many levels of an organization. Some changes can be implemented immediately; others will take time. Some conversations stretch into socioeconomic and political issues that are beyond our control, but about which we need to be aware. For example, a student without a quiet place to do his homework may be living in a small apartment with many people; he may be the eldest responsible for watching his younger siblings while his mother works nights; he may live in an apartment complex on a busy thoroughfare that is a center for the informal economy. These macro issues are hard for a school to exert a direct influence on, but without an understanding of the larger systems at play, our responses to the immediate problems will be misguided, often tend to blame individuals, and are not likely to result in sustainable change. Furthermore, when we understand the larger systemic issues affecting our students and classroom experiences, we may be able to influence decisions made on the political and policy level; for example, we can use this knowledge when voting for school board candidates, we can support organizations that address socioeconomic issues, or we may be less inclined to blame a local district or principal for circumstances outside of their control.

A masterful coach is a leader who by nature is a vision builder and value shaper, not just a technician who manages people to reach their goals and plans through tips and techniques. To be able to do this requires that the coach discover his or her own humanness and humanity, while being a clearing for others to do the same.

Hargrove (2003, p. 18)

The systems-thinking approach in coaching is integrated into many aspects of this book. It is addressed throughout every chapter, and more specifically in Chapters Six and Fourteen.

The Coach's Transformation

Transformational coaching is possible only when the coach is engaged in a process of transforming her own behaviors, beliefs, and being along with the client. Transformational coaching, therefore, is the synergistic outcome from two people engaged in transformation of their individual behaviors, beliefs, and being. Transformational coaching is not something we do to another; it is not a process that is engaged in only by the client. It is a complex dynamic engaged in by both client and coach. Without the coach's participation in her own transformation, the client cannot achieve his goals. Therefore, to take up this kind of coaching necessitates a commitment on the coach's part. This distinguishes transformational coaching from other forms. Chapter Fifteen goes in depth into this process for a coach.

A Vision for Coaching

As coaches learn about this field and explore what kind of coaching they practice, it can be helpful to develop a personal vision statement. Just as a vision statement focuses, empowers, and guides those who work at a school, coaches can also be guided by a vision. When I question why I'm doing what I'm doing, or when I feel unmoored by the challenges in my daily practice, I return to my vision. It helps me remember, it energizes me, and it grounds me.

My vision developed as I learned what coaching means to others in this field. I love collecting quotes about coaching, and you'll find many of these shared in this book. These poetic descriptions often illuminate aspects of coaching that I hadn't recognized before. They inform my vision for coaching.

I encourage all coaches to articulate a vision for coaching. Why do you do what you do? What's the big picture you're working toward? Your vision can be for your eyes alone, or you can share it with others. The process of creating a vision statement is powerful and surprising. You can find suggestions for how to create one online or on my website. Here's my vision:

I coach to heal and transform the world. I coach teachers and leaders to discover ways of working and being that are joyful and rewarding, that bring communities together, and that result in positive outcomes for children. I coach people to find their own power and to empower others so that we can transform our education system, our society, and our world.

A Coach Who Knows Who She Is and Can Travel Back in Time

Here's what I wish I had done when I began working at the school I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. Had I really articulated my role and personal vision as a transformational coach, I think I could have alleviated a lot of anxieties, had more support from the principal, and been far more effective.

First, I would have asked for time at a staff meeting in the very beginning of the year to present myself as a coach. I'd share my vision for coaching, my definition of coaching, and my hopes for what coaching might be able to do at this school. I'd let people know that in order to figure out what my role should be at that site, I'd need to conduct a deep investigation into the site's current situation. I'd let them know that I intended to interview teachers, students, parents, staff, and the administrators to hear about how they defined the school's strengths and areas for growth. I'd let them know that the purpose of doing this was to learn about the school and figure out how I could be most helpful.

At this meeting with the staff, even though I'd be really nervous, I'd also demonstrate a coaching session with a willing teacher so that they could get an immediate sense of how I work. I'd want them to see how I listen, ask questions, and offer support. This would make coaching less abstract and intimidating.

In the interviews, I would have asked teachers about their own learning needs and how they might feel most supported in their learning. Using this feedback, I would have co-constructed my role with the principal, identifying goals that I'd work toward during the year. Chapter Seven goes in depth into this process.

I'd also have a better understanding of what coaching was, what a coach did, what can be expected from coaching, and why a coach does what she does. I'd anticipate the pushback, resistance, and fear that are frequent among those new to coaching, and I would not take these things personally.

Hindsight, of course, is always 20/20. My reflection on how I went into this first coaching scenario helped me tremendously when I began my subsequent coaching job. I was much clearer and more articulate about what I was doing and why. Making mistakes and learning from them are unavoidable parts of being alive. In this book, I am committed to helping new coaches avoid as many mistakes as possible.