IN BRIEF

The Psalms

The prayers of the faithful

From 10th century BCE In the First and Second Temples of Jerusalem.

David The second king of Israel and Judah in the 10th and 9th century BCE. An enthusiastic sponsor of singers and musicians, he was known as the “hero of Israel’s songs” (2 Samuel 23:1).

Asaph A Levite, appointed by David as one of the chief musicians before the Ark of the Covenant in Jerusalem. Thought to have founded a school or guild of temple singers and musicians, known as the “sons of Asaph.”

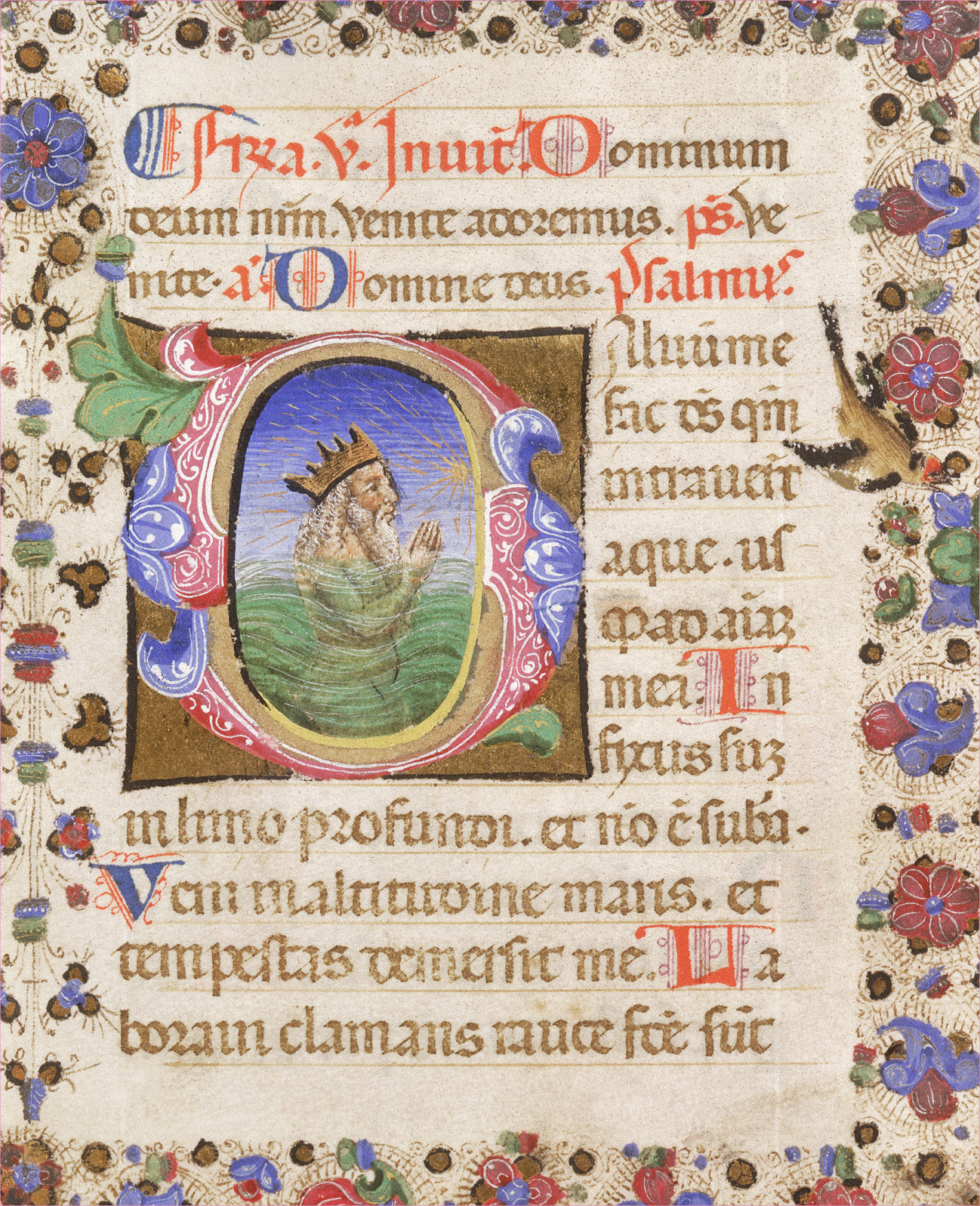

The Book of Psalms as we know it probably dates from the 6th century BCE, after the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile. It was effectively a hymn book for Israel, used in the liturgy of the Second Temple, where Psalms would have been sung to an accompaniment of lyres, harps, and cymbals.

The Psalms can be seen as the human side of a dialogue between Israel and its God. Often they are brimming with positivity, as in the ending of Psalm 23: “Surely your goodness and love will follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” At other times, feelings are bleaker and more raw: “You have put me in the lowest pit, in the darkest depths,” complains the writer of Psalm 88. This broad emotional variance allows the book to cover a range of experiences relating to religious life.

Origins and usage

Like all hymn books, the Book of Psalms draws on earlier collections, many of them already hundreds of years old. Some Psalms bear marked resemblance to hymns used by other Near Eastern peoples—for example, Psalm 104, which has parallels with the Great Hymn to the Egyptian sun god Aten. This is more likely to be because certain types of hymns were common across the various Near Eastern religions than because one culture consciously plagiarized hymns from another. Many of the common Psalm forms were also used in Babylonian and Egyptian liturgies.

Clues to the earlier collections from which the Jewish Book of Psalms was drawn can be found in the superscriptions at the top of some of the Psalms. There are the Psalms of Asaph, for example, which possibly emerged from a tradition associated with Asaph, son of Berechiah, appointed as a temple singer under King David. Another group are the Songs of Ascent, which may have been used by pilgrims to Jerusalem as they climbed the Temple Mount. Although King David is known to have composed songs, the collection labeled Psalms of David was almost certainly inspired by him and events in his life rather than actually written by him.

It is hard to confirm any exact dates for the Psalms, but scholars emphasize their link with early Temple worship before and after the exile, and traditional Jewish festivals—especially those in the fall before the harvest. It is likely that at least some of these songs and hymns were composed specifically for festival use and would have played a crucial part in the ritual life of early Jews.

Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, my Savior and my God.

Psalm 42:5

Thematic groupings

The 150 Psalms are divided into five books—possibly to reflect the structure of the Pentateuch—and each book concludes with a doxology, a short formula of praise, usually starting: “Praise be to the Lord …” They contain a variety of styles and themes. Many are about royal events related to the reign of King David—73 in total bear his name—while others are more prophetic in nature, or impart an obvious moral lesson. Side by side with grand hymns of glory and devotion sit the more somber Psalms, often of individual or communal lamentation. In fact, laments constitute a major portion of the Psalms—around 40 of the total 150. They almost always conclude in trust and praise, but in their initial forthrightness they say much about the heartfelt directness and honesty of Israel’s liturgical life.

“I love you, O Lord, my strength. The Lord is my rock, my fortress and my deliverer; my God is my rock, in whom I take refuge.”

Psalm 18:1–2

Crying out to God

The causes of lament vary from betrayal to imprisonment and sickness. They are often on behalf of a specific figure, who typically plunges straight into his complaint. “How long, Lord?” is Psalm 13’s exasperated opening. “Will you forget me for ever? How long will you hide your face from me?” In this case the psalmist’s troubles stem from the activities of an enemy. Having stated the complaint, the psalmist then makes a petition: “Look on me and answer, Lord my God. Give light to my eyes …”—the light of restored vitality and joy. To add persuasive power to the petition, he gives reasons for God to act: if God fails to help him, his enemies will say they have overcome the psalmist, which may reflect badly on his God. Having now unburdened himself, the writer of Psalm 13, as in many of the other lament Psalms, switches somewhat abruptly to praise, remarking, “But I trust in your unfailing love; my heart rejoices in your salvation.”

One possible reason for this sudden change of tone may lie in the context of temple worship. The psalmist’s complaint and petition may have been part of a dialogue with a priest or temple official who, speaking in God’s name, then pronounced an oracle telling him to go in peace, assured that God had heard his prayer. Whatever the reason, the writer concludes that God “has been good to me.”

Hebrew poetry

Almost a third of the Hebrew Bible is poetry. The narrative books are interspersed with poetic passages; large parts of the prophetic books are in verse; and most or all of Proverbs, Lamentations, Job, and the Psalms are poetry. Meter, as it is known in the Western tradition, does not exist in Hebrew poetry, nor does rhyme. Instead, its key building blocks are short lines in pairs, as, for example, in the opening of Psalm 24: “The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it, the world, and all who live in it.” The second line often repeats the meaning of the first, to create a sense of balance or symmetry. The effect is also cumulative, with the second line amplifying the scope and resonance of the first. Another device in Hebrew poetry—one that inevitably gets lost in the translation—is the acrostic, in which each line or group of lines begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Nine psalms are organized in this way, notably Psalm 119.

Historical laments

Other Psalms are of communal lament, many arising out of the humiliation of defeat. For the final editors of the Psalms, no defeat was more recent or searing than the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple by the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Psalm 79, one of a small number of Psalms emerging from that experience, opens with a description of the disaster: “O God, the nations have invaded your inheritance; they have defiled your holy Temple, they have reduced Jerusalem to rubble. They have left the dead bodies of your servants as food for the birds of the sky, the flesh of your own people for the animals of the wild.”

It continues with a mingling of praise, repentance, and anguished petitions for salvation, justice, even vengeance: “Pay back into the laps of our neighbors seven times the contempt they have hurled at you, Lord.” Elsewhere, the desire for revenge burns most appallingly in another psalm of the exile, Psalm 137. Its conclusion is a howl of bloodthirsty rage: “Daughter Babylon, doomed to destruction, happy is the one who repays you for what you have done to us. Happy is the one who seizes your infants and dashes them against the rocks.”

“By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept when we remembered Zion. There on the poplars we hung our harps, for there our captors asked us for songs.”

Psalm 137:1–3

Joyous Psalms

Psalms written in the light of an answered prayer are usually more jubilant. Typically, they tell or suggest the whole story: the trouble the psalmist was suffering, how he made a lament to God, and how God wonderfully intervened. “I will exalt you, Lord,” begins Psalm 30, “for you lifted me out the depths and did not let my enemies gloat over me.” Despite the reference to his enemies, the psalmist’s distress seems to have been a sickness that brought him close to death. He cried to God for help, and God healed him, sparing him “from going down into the pit.” The conclusion here is a shout of praise and thanksgiving: “You turned my wailing into dancing; you removed my sackcloth and clothed me with joy, that my heart may sing your praises and not be silent.”

Songs of praise

Hymns of collective praise are among the most majestic of the Psalms. They tend to have the simplest structures: a summons to praise God, followed by reasons for that praise. “Praise the Lord, all you nations; extol him, all you peoples,” the shortest psalm of all, Psalm 117, commands: “For great is His love toward us, and the faithfulness of the Lord endures forever.” In other cases, the opening summons leads to a list of God’s interventions on Israel’s behalf.

Perhaps the most beautiful Psalms are the songs of creation, such as Psalm 104, which elicit praise by extolling the creator-God. He is the God who “makes the clouds His chariot and rides on the wings of the wind.” Not only does creation reflect His splendor, but also His provision for humankind: “He makes grass grow for the cattle, and plants for people to cultivate—bringing forth food from the earth.”

What is remarkable about the Psalms is the energy and feeling behind the words. Whether they are praising or petitioning God, they each show a very human side of the Bible, where people are unafraid to confess their multifaceted emotions to a benevolent Lord.

A shepherd and his flock

The image of a leader as a shepherd goes back to the 3rd millennium BCE when the kings of Sumer in Mesopotamia described themselves as shepherds of their people. In societies where herders were part of everyday life, it was an obvious comparison to make, and other nations followed this example.

For the Israelites, David was the archetypal shepherd-king, who literally started life as a shepherd. But above him was the one who fulfilled that role supremely: God (as stated in Psalm 23). In the 6th century BCE, during the Babylonian Exile, the prophet Ezekiel used the imagery of a shepherd in a furious tirade against Israel’s leadership: “Woe to the shepherds of Israel who only take care of themselves! … you do not take care of the flock.” Jesus continued the tradition, describing the crowds who followed Him as “like sheep without a shepherd,” and later referring to himself as a “good shepherd [who] lays down His life for the sheep.” The image lives on to this day in the word “pastor,” Latin for “shepherd.”

See also: David and Goliath • The Nature of God • Proverbs • Song of Songs • Parables of Jesus