IN BRIEF

Proverbs

Blessings for the faithful

c.700–500 BCE King Hezekiah’s palace and a place of instruction post-Exile.

Solomon A king of legendary wisdom who is said to have uttered 3,000 proverbs. The bulk of the book of Proverbs is attributed to him.

Hezekiah King of Judah from 715–698 BCE. According to Proverbs 25:1, the earliest maxims, contained in chapters 25–29, were transcribed at his court in Jerusalem.

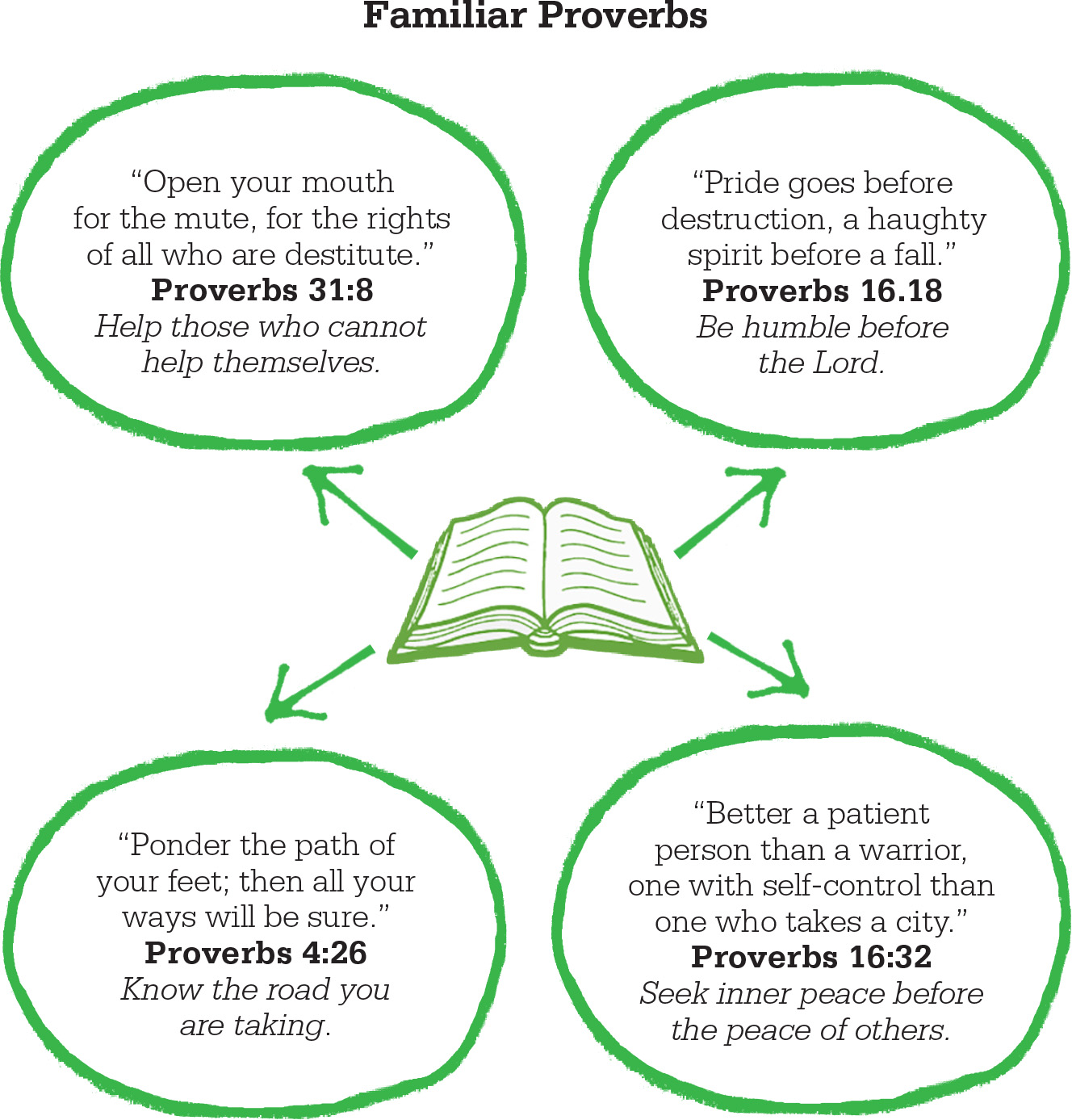

The book of Proverbs is a book of advice, or wisdom literature, which seeks to instil “knowledge and discretion” (1:4) in young men about to forge their ways in the world. The aim is that such men will not only live a fulfilling and prosperous life, but also a moral one. While the book of Proverbs makes it clear from the outset that the “fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge” (1:7), much of the book’s focus is not directly on God, but on the choices and dilemmas faced in daily living.

The pragmatic advice comes in the form of short admonishments and pithy encouragements. A warning against laziness, for example, says: “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider its ways and be wise!” (Proverbs 6:6). Many of the book’s maxims date back millennia, and a number come from outside the Israelite tradition—some, for example, are borrowed from Egyptian wisdom literature.

Historical collection

Authorship of much of the book of Proverbs is attributed to King Solomon, although this is unlikely. It is more probable that the Proverbs were gathered into collections at various times in Israelite history and then copied at the Judean court of King Hezekiah in the late 8th century BCE. In view of the customs mentioned and the pure monotheism espoused by the text, the book as it appears today almost certainly dates from the late 6th century or 5th century BCE, after the Judeans had returned from exile in Babylon.

The scribes organized Proverbs into five sections with four short appendices at the end. The first section or prologue (chapters 1–9) most obviously bears the imprint of the post-Exile period, although it is labeled “The Proverbs of Solomon.” Next comes a long section (10:1–22:16) of short, mostly two-line proverbs, attributed to Solomon, and then the section entitled “the sayings of the wise” (22:17–24:22), which shows Egyptian influence. This is followed by another short section on the same theme (24:23–34), and then another longer section (chapters 25–29) attributed to Solomon. The appendices make up the last two chapters and conclude with a famous poem extolling the virtues of “The Wife of Noble Character” (see here).

Wisdom literature

Proverbs, along with the Books of Job and Ecclesiastes, belongs to a well-established genre of the ancient Near East: wisdom writing. Consisting of maxims and tales that reflect upon life wisely lived, this body of literature has deep roots. One of the oldest known works is the Maxims of Ptahhotep, from the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, which details the instructions of a vizier to his son. The Instruction of Amenemopet—written down around 1000 BCE but probably older than that—also follows a similar format. The section in Proverbs entitled “sayings of the wise” is clearly modeled on Amenemopet’s maxims and includes some that are almost identical. Similarities also exist with a Mesopotamian work: the Story of Ahikar. The tale of a chief counselor at the Assyrian court, it is peppered with wise sayings. The sayings include an earlier version of the Bible’s famous “spare the rod, spoil the child” proverb.

Twin strands

Wisdom in Proverbs is delivered through two voices. One is that of an elder—a parent, teacher, or sage—giving instruction to a younger person. The book’s very first exhortation is in this style: “Listen, my son, to your father’s instruction and do not forsake your mother’s teaching” (1:8). The figure who conveys teaching is Wisdom, personified as a woman. “Out in the open Wisdom calls aloud, in the street, she raises her voice in the public square” (1:20), the first proverb in the book relates.

There is a contrast in tone between the two strands. While the maxims of the elder, the bulk of the book, tend to appeal to reason and good sense, the teachings of personified Wisdom are more emotive, approaching at times the admonishing tones of the biblical prophet: “How long will you who are simple love your simple ways?” Wisdom cries out. “How long will mockers delight in mockery and fools hate knowledge?” (1:22).

Teaching in the proverbs is mostly presented in one of two forms: the instruction and the saying. Used in the first nine chapters, the former develops an idea—the perils of idleness, for example—in a poetic paragraph a few lines long. The saying, the form that dominates most later chapters, is more succinct. It is a statement, usually of two lines, that presents a truth in a way intended to stay in the mind, often by virtue of a paradox. Possibly the most famous proverb of all works like this: “Whoever spares the rod hates their children, but the one who loves their children is careful to discipline them” (13:24).

A variation on the paradox is the numerical proverb, which lists items that have something in common and then ends with an ironic twist. One example is this reflection: “There are three things that are too amazing for me, four that I do not understand: the way of an eagle in the sky, the way of a snake on a rock, the way of a ship on the high seas, and the way of a man with a young woman” (30:19).

Domestic focus

Perhaps because of its place within the wider wisdom tradition of the Near East, the Book of Proverbs differs from much of the rest of the Hebrew Bible in that it never mentions Israel’s history. Its approach is for the most part observational. Proverbs is clear that God lies at the heart of reality and about the need to be humble as a result. “Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding” (3:5) is one of its admonitions. Wisdom, it suggests, is learned through God. The maxims it offers on human affairs focus on areas such as family, anger, poverty, and righteousness, but cannot be truly heeded without fear of the Lord.

“Blessed are those who find wisdom, those who gain understanding, for she is more profitable than silver and yields better returns than gold.”

Proverbs 3:13–14

Wisdom incarnate

Proverbs makes intriguing claims about God and heaven in the voice of personified Wisdom. She speaks of how she is “the first of His works” (8:22), continuing: “I was there when He set the heavens in place” (8:27). She even claims to have been a craftsperson at God’s side during creation.

This idea would be later picked up and developed by New Testament writers, notably the author of John’s Gospel. He sets out the idea of the Logos, or Word, who “was with God in the beginning,” through whom “all things were made” and who became incarnate as Jesus. Proverbs’ personified Wisdom contributed to the idea of God’s wisdom incarnate being a part of the Holy Trinity, leading to the establishment of the later doctrine of Jesus’s incarnation (see here).

Eshet Hayil

Proverbs’ final half chapter is an acrostic poem—one in which each stanza begins with a succeeding letter of the Hebrew alphabet—extolling the virtues of a woman of “valor” or “noble character.” Eshet Hayil in Hebrew, this woman is the perfect wife and mother, whose “worth is far more than rubies” (31:10). By no means confined to the home, she works hard, has a good business head, and is generous to the poor. Presiding over her household with dignity, she brings honor to her husband, who finds himself “respected at the city gate, where he takes his seat among the elders of the land” (31:23).

The portrait the Eshet Hayil creates has resonated over the centuries, and in devout Jewish households it is often sung or recited at the start of the Kiddush, the Friday evening ceremony that ushers in the Sabbath. According to the mystical kabbalistic tradition of Judaism, it refers to God’s Shekhinah, or divine presence, associated with a maternal, nurturing role. In other interpretations, it can be seen more simply as the family paying tribute to the mother. The passage that proceeds the acrostic narrates the lessons King Lemuel has received from his mother, so the poem may also be his own glorifying eulogy for her in return. In some households the Eshet Hayil is balanced with a recital of Psalm 112: “Blessed are those who fear the Lord, who find great delight in his commands.”

See also: The Ten Commandments • The Wisdom of Solomon • Sermon on the Mount • The Golden Rule • Parables of Jesus