Chapter 8

Leadership: What It Takes to Make a Leader

More organizations have committed to spending more money on leadership development in the past couple of years than on any other topic. Is it any wonder? The most valuable investment any organization can make is the development of its future leaders. This vital task ensures that leaders possess competencies to achieve the organization’s strategy, continue to mature the organizational culture, and inspire the workforce.

Due to the upcoming Baby Boomer exodus from the workforce, many organizations face losing 30 to 50 percent of their key leaders in the next half-dozen years. Unfortunately, many organizations have been lax in developing new leaders to replace the current generation of leaders. At the same time, the essential leadership skills expected of new leaders continues to climb. Senior leaders’ positions are more challenging than ever and require a broader range of job experience and a surprisingly long list of competencies.

In addition to what we typically think of as required leadership skills, the next generation of leaders must bring a sophisticated set of new skills. The next generation must be visionary coalition-builders; internationally astute; quick learners and fast implementers; highly creative; comfortable with change, volatility, and ambiguity; intimately aware of changing customer needs; agile enough to revamp operations instantly; and able to produce rapid results in all areas.

The breadth of required leadership competencies demonstrates that every forward-looking trainer must work to meet this challenge. Ask yourself questions such as: “What am I doing to prepare our next generation of leaders? What skills are required for our organization? Am I prepared to deliver skills and knowledge that will help future leaders learn and prepare for their jobs?”

The journey to becoming a good leader may be long and filled with potential potholes—and may even lead to a few dead ends. This chapter will help you prepare leaders by addressing critical topics that will make their journey easier, including skills such as: strategic thinking, setting goals, building trust, addressing values, creating a vision, and focusing on ethics.

All of the activities in this chapter will give your leaders a chance to practice and improve their decision making capacity. The first activity, “The Great Leadership Debate,” presented by Lisa Rike, addresses the importance of critical thinking in leaders. Barb Crockett’s activity, “What a Difference a Goal Makes,” is short but offers a tremendous amount of learning. She introduces an effective experiential learning activity to show leaders the importance of setting specific and measurable goals. Mel Schnapper, from Holland, introduces “Create a Vision,” which he has used all over the world. Lisa Rike’s second activity in this chapter, “Power of Questions,” demonstrates how you can show your leaders the importance of asking questions. Cindy Phillips adds a trust activity.

The last two activities address how leaders make ethical and value-driven decisions. Both are heady and require an investment of time (close to two hours each), but they are well worth the time spent. Jeff Furman introduces us to ethicist Randy Cohen and uses his New York Times column, “The Ethicist,” as a basis for learning. Abu Dhabi learning professionals P. Sethu Madhavan and Yehya M. Al Marzouqu demonstrate how difficult it can be to make decisions based on values.

Is leadership development on your action list? These activities are sure to help you.

Overview

Leaders in this activity use a traditional debate format to gain insights into critical thinking and looking at both sides of an issue. It’s a great activity for leaders and high-potential contributors.

Objectives

- To develop critical thinking skills in leaders

- To practice considering different points of view

- To make informed decisions

Audience

Six to twelve members of a leadership team, with additional participants used as coaches for each side

Time Estimate

45 to 55 minutes

Materials and Equipment

- Flip chart with extra paper

- Markers

Area Setup

Any room in which half of the participants can comfortably sit across from the other half

Process

1. Ask the participants for examples of real issues they face as a leadership team that they believe hinder the team’s job performance. Examples include:

- Unequal company benefits to full-time and temporary employees

- Leaders showing favoritism to certain staff

- Whether the employees trust the company leaders

- Numerous meetings that interfere with leaders’ ability to spend “face time” with staff and complete tasks

- Lack of relevant information communicated consistently throughout the organization

2. Describe the goals of the activity and explain that the participants will have an opportunity to practice various aspects of leadership, including the skills needed to make informed decisions, practice critical thinking, and other aspects important for an issue of their choosing.

3. Select or ask the participants to select the issue they will debate. Write the selected issue on a flip-chart page so that all can see it.

4. Randomly divide participants into two equal groups. Arrange the participants’ chairs into two lines facing each other. Tables can be used, but they are not required.

5. When the participants are seated, assign one side to debate the affirmative view and the other side to debate the negative view.

6. Explain these rules to the participants:

- They will debate the group’s chosen issue from two opposing points of view, for example, whether or not an issue or situation exists or whether or not the benefits are worth the risks.

- Explain that each side is allowed to make one statement/point at a time. Once the point or statement is made, the other side has a chance to either refute the statement/point or state something that supports their own assigned point of view.

- Everyone on each side must stay in character and represent their assigned points of view and make their points as valid as possible.

- It is not necessary to rebut every single point raised by the opposition. Single out the opposition’s main arguments and attack those first. Show the weaknesses in the other team’s case and show why your case is better.

- All members of each side must participate. No one may dominate the debate. Participants should encourage one another to contribute.

7. Ask one side to start. Establish a time limit for the debate, usually 8 to 10 minutes. Stop the debate at the agreed on time.

8. Tell the participants to switch roles so that the side making the original affirmative argument is now on the negative side and the participants on the original negative side will now take the affirmative side.

9. Restart the debate and allow it to continue for approximately 5 minutes.

10. Stop the debate and ask these questions to debrief the experience:

- How was your experience debating both sides of an issue?

- Which was easiest to argue?

- What argument was more difficult for you?

- What did you learn being forced to look at both sides?

- As a leader, what is the value of looking at both sides?

- What skills are required to make informed decisions? What do you consider to be the risks, impact, benefits, or advantages of informed decisions?

- How can this type of activity help you to become better strategic thinkers or to make more informed decisions?

- Why is critical thinking an important skill for leaders?

- How can you continue to practice the skills we’ve practiced here today?

- What might you do differently on the job as a result of participating in this activity?

11. Make the point that being a strategic leader means seriously considering both sides and all points of view before making decisions.

InSider’s Tips

- I’ve used this activity for years. If the participants struggle to come up with a point to make, don’t let them pass. Let them know they are expected to respond as if they were committed to that point of view.

- Many participants tell me that they had an “aha” about the issue during these debates.

What a Difference a Goal Makes

Overview

Teams of leaders work on an assigned task that is either very achievable or extremely difficult, depending on the assignment instructions, and learn valuable lessons about goal setting.

Objectives

- To demonstrate the benefits of specific and measurable goals

- To discuss the importance for leaders to set specific goals

- To have fun through team competition

Audience

Three teams comprised of five to ten leaders each (If you have more than thirty participants, divide the group into six teams and double the required materials.)

Time Estimate

20 minutes

Materials and Equipment

- Three sheets of paper prepared as instructed below, one question per page

- Pens or pencils for participants

Area Setup

Enough space so that the three teams are far enough away from each other that they cannot easily hear the other discussions

Preparation

Create the instruction sheets by writing one of the following on three separate sheets of paper:

Sheet 1. Name as many ideas for incentives as you can.

Sheet 2. Name as many ideas for incentives that you can in 10 minutes.

Sheet 3. Name fifty ideas for incentives in 10 minutes.

Fold each sheet in half and write the task number on the folded sheets: 1, 2, or 3.

Process

1. Start the activity by saying, “We are going to have a contest. Let’s get into three teams by counting off by 3’s.”

2. Assign a location for each of the three groups and tell the participants to move to the assigned space. Continue by saying, “Each group has an assignment on a slip of paper. After I distribute all three sheets, you may look at them and share them within your team, but don’t read the instructions out loud. Talk among yourselves but don’t let the other teams hear your task or your ideas.” Tell the participants that they will have 10 minutes to complete the assignments listed on their sheets.

3. Ask the group to begin working and start the timing period.

4. At the end of 10 minutes, call time. Ask each group to count the number of ideas they were able to list. Groups 1 and 2 usually have about the same number on their lists. Group 3 typically blows away the competition.

5. Ask each team to read their assignment out loud beginning with Group 1 and to state how many ideas they listed.

6. Summarize with a discussion around these questions:

- How many of you were surprised that you had different tasks? Why?

- What were the differences?

- How do you think the different wording of the tasks affected the results?

- What were you measuring yourselves against to determine success? Note: The members of Group 3 count and measure themselves against the target the entire time.

- What can you surmise based on the results?

- What advice would you give leaders about setting goals?

- How can you apply this to your work? Personal life?

InSider’s Tips

- I have tried variations on this activity. For example, I tried one hundred ideas instead of fifty, but one hundred is not attainable. I have tried 5 minutes instead of 10 but have found that 10 minutes works best.

- I have conducted this activity eight to ten times with different groups and have always achieved similar results.

- It is a good illustration of SMART goal setting. Setting the time limit for Group 2 did not make a significant difference, but setting the specific goal of fifty did. Usually Groups 1 and 2 don’t even count how many ideas were on their lists until asked to do so.

Overview

Participants are asked to draw upon their artistic skills to draw pictures that represent a higher functioning, more cohesive group or team. Appropriate for any team, department, or group.

Objectives

- To create a pictorial vision of how a group works together

- To identify ways a group could function better in the future

- To discuss best practices for leaders who are establishing a vision

Audience

Up to twenty participants from intact work teams

Time Estimate

30 to 60 minutes, depending on discussion

Materials and Equipment

- Flip chart with paper for each subgroup

- One set of markers of various colors for each subgroup

- (Optional) Crayons

- Masking tape

Area Setup

Tables arranged so that participants can work in groups

Process

1. Ask the participants whether they have ever had a mental picture of how they would like their group to work. State that this activity will give them an opportunity to create and share their ideas. Ask them to form into their work groups of four or five each. (Divide larger work groups into smaller subgroups.) Give each group a flip chart and a set of markers.

2. Tell the participants to use the markers (and crayons if provided) to create a picture on the flip-chart without words or numbers. Ask half of the groups to draw a picture that represents how they function as a team/department/organization today. Ask the other groups to draw a picture of how they would like to function in the future. Tell them they have 20 minutes to create their pictures.

3. After the allotted time, ask each group to select someone to present their pictures to the large group.

4. Ask the groups assigned to draw a picture of how they function today to present their pictures first. Hang the flip-chart pages along a wall. Applaud after each presentation.

5. Ask the groups assigned to draw a picture of how they would like to function in the future to present their pictures. Hang the flip-chart pages along a wall. Applaud after each presentation.

6. Lead a discussion about the pictures using some of these questions:

- What happened as you worked together? What was the atmosphere like?

- What did you learn about yourself? What did you learn about your group?

- How does this relate to what happens on a day-to-day basis in this group?

- What differences do you see in the pictures of how you function today and how you would like to function in the future?

- What can you do differently that would move you closer to how you would like to function?

- What did this activity tell you about visions?

- How could a leader use this concept to create a vision?

- What advice would you give a leader who is establishing a vision?

- How can you ensure that you make changes that move you closer to your desired future?

7. Summarize by encouraging the small groups to come together again to establish action plans for future improvement.

InSider’s Tips

- You may wish to use an observer to see how each small group handles the assignment. These observations (and your own) can be shared in the debriefing period.

- Be flexible regarding time and allow for discussion going in a direction you did not expect.

- This activity works in every country where I’ve used it including Nigeria, Indonesia, and China.

Overview

Participants use role play to switch between the positions of leader and employee and discover the value and appropriate use of an “asking” leadership style versus a “telling” style.

Objectives

- To improve leaders’ listening skills and their understanding of others

- To discuss how asking more questions can benefit leaders

Audience

Two to twenty leaders

Time Estimate

30 minutes or more

Materials and Equipment

- Flip chart

- Markers

Area Setup

A room with adequate space for small groups to gather apart from other groups

Process

1. Ask participants for examples of topics leaders discuss with their employees, such as performance or attitude issues. Write these suggestions on a flip-chart page.

2. Divide the participants into subgroups of four or five participants each. Tell participants that each group will designate a leader and an employee. The rest of the group will be the observers. The “leader” will facilitate a discussion with the “employee” based on one of the topics you recorded on the flip chart. During that discussion, the leader may only ask questions. The leader must keep the interaction going and not pause to think for more than a 10 or 15 seconds before asking the next question. Comment on the activity by saying, “Here’s a tip: Leaders, listen intently about what the employee is saying and ask each question based on what you hear to probe the situation further.”

3. Tell the observers that their job is to keep the leaders honest in asking only questions. If the leader “chokes” and doesn’t ask a question or hesitates for more than 15 seconds, one of the group observers should volunteer a question or volunteer to be the leader. Each observer must stay focused on the interaction between the leader and the employee and be ready to ask a question based on what he or she just heard. Observers can volunteer each other to be the next leaders as well. Tell everyone this first interaction will last about 5 minutes. Tell them to select a topic and to begin the discussion.

4. Begin timing the activity.

5. After 5 minutes, call time and ask the small groups to select another topic and switch roles. Tell the groups that they should select another topic to use from the flip chart at any time. Remind them that everyone should have a chance to be the leader and that they should allow each member be in the role of the leader for at least 3 to 4 minutes before switching.

6. Roam around the room during the activity and listen to the interactions. If a group is stuck and not sure of a question to ask, coach the group to ask a very broad, open-ended question such as:

- “What else contributes to this situation?”

- “What else can you tell me about how that happened?”

- “What else have you tried?”

- “What else can you try?”

- “What might hinder your progress?”

Remind the participants that asking broad, open-ended questions allows the leader to learn more about the situation and gather their thoughts about what questions to ask next.

7. Stop the small group activity after everyone in the group has been a leader.

8. Ask the participants to take their seats and summarize the activity using questions like these to debrief the experience:

- What was it like to be able to only ask questions?

- Did you find yourself asking leading questions such as “Have you tried. . .?” and broad, open-ended questions such as “What are your ideas to improve this situation?” and closed-ended questions where “yes” or “no” are the only responses?

- How is being able to use different types of questions useful to a leader?

- What is your natural leadership tendency—to tell more or to ask more questions?

- As a leader, what will you do as a result of participating in this activity when you return to the workplace?

9. Make the point that leaders are also talent managers who develop their employees. Note that asking questions engages employees in the discussion and causes them to think and develop abilities to solve problems. Point out that employees are more likely to buy into what is expected of them when they have a say in it. Also emphasize the appropriate use of “telling” and “asking” questions. (The majority of leaders tend to tell more than ask, which means they are missing opportunities to develop their employees to think for themselves and self-coach.)

InSider’s Tips

- One concern typically expressed about asking more questions versus telling employees the answer is the amount of time it takes to have this type of interaction. While it is true that “asking” does take more time, the value outweighs the investment of time. Here are some points to share about this:

- This is one of the reasons the leaders only had 10 to 15 seconds before someone else took over for them. This change forced them to see how efficiently they can use questions.

- In the short term, the interaction does take longer but the long-term potential gains are worth the initial time investment. The employees must come up with answers and ideas that help them practice how to self-coach. Eventually, they will coach themselves without asking for the leaders’ help.

- This is not suggesting that leaders should only ask questions. The activity was structured this way to help them remember to seek ways to ask more questions than they do now.

- Asking questions also provides a deeper understanding of the employee’s view of the situation.

Overview

Participants explore the issue of trust as well as their own preferences, likes, dislikes, and concerns surrounding the issue by taking sides—literally!

Objectives

- To begin a dialogue about both the positive and negative aspects surrounding the issue of workplace trust

- To demonstrate how everyone has a different orientation toward trust

- To discuss dimensions that impact trust

Audience

Eight to fifty with adequate space

Time Estimate

At least 45 minutes; may vary based on the questions

Materials and Equipment

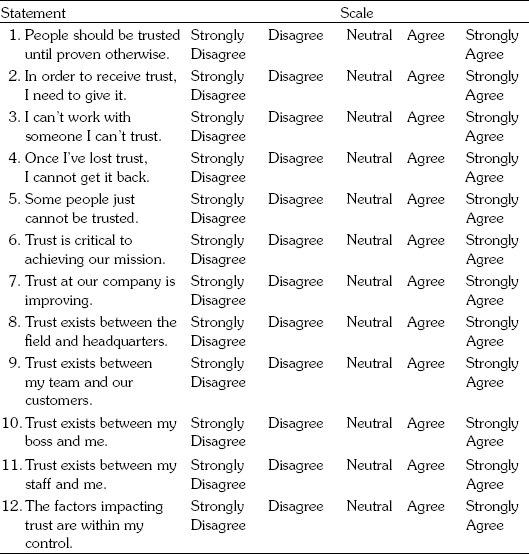

- One Vote Trust handout for each participant

- Pencils or pens

- Five 8½ × 11 signs taped to the wall or floor in order: “STRONGLY DISAGREE,” “DISAGREE,” “NEUTRAL,” “AGREE,” and “STRONGLY AGREE” in large font

- Masking tape

Area Setup

A room large enough for participants to stand in five general areas near five signs posted equally spaced along one wall or in the corners and center of the room

Preparation

Customize the handout for your needs, changing the names of groups or adding other more pertinent statements.

Process

1. Provide all participants with copies of the Vote Trust handout and pens or pencils. Ask them to complete the handout quietly where they are seated.

2. Ask the participants to stand, taking their completed handouts with them.

3. Read the first statement you want to discuss. Ask participants to stand under the sign that represents their views on this statement.

4. Ask volunteers from each of the extreme responders (“strongly disagree” and “strongly agree”) to explain their views. You may also want to ask someone from the neutral group if it seems relevant. Discuss the responses from the volunteers. You may wish to ask other questions such as:

- What concerns do you have based on the responses to this question?

- What positive aspects do you see in the group’s responses?

- What does this tell you about the different orientation each of you has toward trust?

- What dimension is impacting trust with this statement?

5. Repeat this process with each of the other statements until you have covered all the statements that are relevant for this group. Ask the participants to take their seats.

6. Summarize this activity by asking questions such as these:

- What did this activity demonstrate about trust?

- What did you learn about yourself? About your colleagues?

- How does trust affect what you do at work? Negatively? Positively?

- What impacts trust?

- How might this activity explain what happens in the workplace with regard to trust?

- How do leaders build trust?

- What is a leader’s responsibility in building trust?

- How can you transfer what you have learned to the workplace?

InSider’s Tips

- Don’t ask every question on the handout; select the ones that seem most relevant to the group and their culture.

- You do not need to ask the questions in order on the page. Instead, ask questions in a sequence that would likely shift the majority from one side of the room to the other to achieve some physical movement.

- Allow the participants to talk; they will make the case for you.

- Balance the discussion among all participants; sometimes one person has a lot of energy on a topic and could easily dominate the discussion.

- This is my variation of an activity I took from Casey Wilson, who borrowed the concept from someone else.

Vote Trust

Overview

Leaders face and discuss current ethical dilemmas and questions using a widely read ethicist column to spur debate.

Objectives

- To discuss and consider various aspects of ethical decisions and social responsibility

- To practice responding to ethical issues from different points of view

- To open the discussion about the ethical role of a leader

Audience

Eight to twelve participants

Time Estimate

90 minutes

Materials and Equipment

- Copies of current and one or two past columns of “The Ethicist,” found in The New York Times

- An Internet link to the podcast version of the column online, where the letters are read by actors and then columnist Randy Cohen reads his replies to the letter-writer. The link is www.learnoutloud.com/Podcast-Directory/Philosophy/Ethics/New-York-Times-The-Ethicist-Podcast/22321

Area Setup

A room with wireless access with the ability to connect to the Internet. PCs or laptops should have working sound cards.

Process

1. To introduce this topic, ask participants how many are faced with an ethical decision at work. Ask for two examples and how these sometimes difficult decisions are made. Tell the participants that during this activity they will have an opportunity to discuss and consider various aspects of ethical decisions and to practice responding to them from different points of view. Hand out copies of “The Ethicist” column you downloaded and printed prior to the session to all participants.

2. Ask for a volunteer read out loud one of the letters to “The Ethicist.” Tell them that each letter is from a real person who is currently dealing with an ethical issue and that the author sent a letter to Randy Cohen at The New York Times asking for his advice on how to handle the problem.

3. Ask the volunteer to read the letter. Stop the reader before he or she reads the columnist’s response.

4. Ask participants to think for a few minutes about how they would respond to the letter.

5. Give the participants a few minutes to re-read the letter to themselves and think about their responses.

6. After an appropriate amount of time, ask how the participants would respond. Allow 5 to 10 minutes for discussion, depending on the interest level in the topic.

7. Ask another participant to read Randy Cohen’s response and ask for their reactions to the response.

8. Repeat this process for several other letters, depending upon the issues and time available.

9. If possible, ask the participants to use their computers to listen to Randy Cohen and actors read the same podcast letter (s) and response (s) in order to get a new perspective through a different presentation of the issue.

10. Lead a discussion about the ethical issues participants are currently experiencing on the job. Encourage participants to give each other advice about how to handle their ethical dilemmas.

11. Summarize the discussion by asking a few questions such as:

- What did you discover about making ethical decisions?

- What aspects come into play when making ethical decisions?

- What social responsibility do you have in the workplace when making decisions?

- Why is it so difficult to make ethical decisions? Isn’t it just a matter of right or wrong?

- What is different about a leader’s responsibility when making ethical decisions?

- How do individuals’ personal perspectives affect ethical decisions?

- What is the one most important lesson you are leaving here with today? How will you implement it on the job?

12. End the activity by encouraging participants to look for “The Ethicist” and other ethical columns in newspapers and to start to reading them. Tell them that a part of any job is to make good ethical decisions. Remind them that it’s an ongoing challenge to come up with the most ethical solutions to any issues.

InSider’s Tips

- This always works very well because it involves a great deal of participation without putting anyone on the spot. Participants have fun reading the columns aloud. They find it thought-provoking to review ethical dilemmas that others are facing and to have the opportunity to provide their opinions.

- Hearing various actors reading the letters on the podcasts and hearing the author, Randy Cohen, read his responses adds excitement. This often causes participants to see the letters a little differently from how they read them earlier. You can suggest that participants continue to explore their own answers to ethical columns or blogs. This reinforces the learning objective that there are multiple ways of seeing ethical issues.

- “The Ethicist” column, found in The New York Times, addresses ethical current and relevant ethical issues. You may find other columns or newsletters that address ethical issues.

- Reinforce the idea that everyone thinks his or her view is correct on issues of ethics, and point out that we all need to recognize this tendency in ourselves. Emphasize that making ethical decisions is as much an art as a science and that many different points of view exist. State that the person writing the letter is usually unhappy with someone else and feels he or she is ethically right. However, the person on the other side of the issue also usually feels strongly that he or she is right. Try to get participants to think about who is more correct, but also to empathize with both sides.

- Note that “The Ethicist” column is published in The New York Times, which is not public domain material. I do have written permission from the author of “The Ethicist” column, Randy Cohen, to use his columns in my classes in this manner. I recommend that you also obtain permission from him to avoid any copyright issues.

Overview

Popping a balloon never had as many positive learning opportunities as in this fast-paced, highly interactive activity that also gives the facilitator the chance to mystify and intrigue with a magic trick.

Objectives

- To provide an opportunity for participants to share personal experiences and insights related to dilemmas around values or conflicts experienced at work

- To develop the participants’ awareness and understanding about their own value judgments as well as those of others

- To demonstrate how values affect decisions and problem solving at work

- To discuss a leader’s responsibility to uphold an organization’s values

Audience

Ten to twenty-five participants

Time Estimate

Approximately 2 hours

Materials and Equipments

- One thin sewing needle to demonstrate the age-old “magic balloon” trick (See Insider’s Tips below for an explanation of the “trick.”)

- Five to ten inflated balloons of any size for the participants to try piercing with the needle without bursting them

- A container with medium-sized balloons of different colors or patterns to divide participants into small groups (If colors are not available, write numbers on the balloons to represent different groups.)

- CD markers for participants to write on the balloons

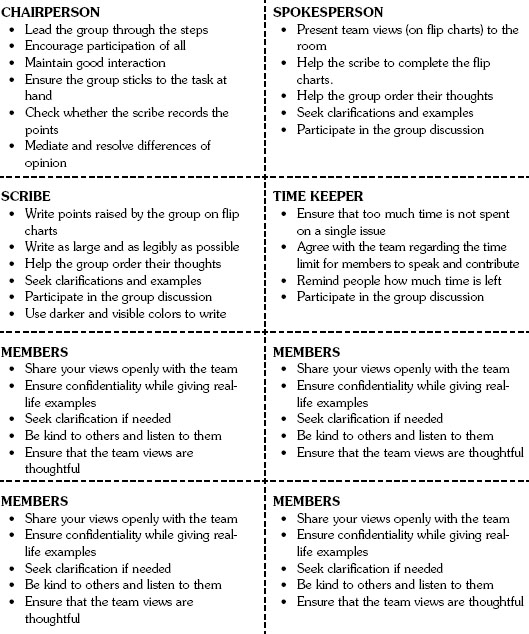

- One set of roles for each group (The sheet describing the “Member” role may be colored differently.)

- One inflated balloon for each group labeled “Roles” and filled with one set of roles

- Incidents describing the value dilemmas from real life

- One inflated balloon for each group that is labeled “Incidents” filled with critical incidents

- A flip chart or slide showing the questions for the groups to address during the discussion

- One flip chart and markers for each group

- Flip chart and markers for the facilitator

Area Setup

A large room capable of accommodating all groups, which should be able to see and hear each other without disturbing one another

Preparation

Copy the Roles and Incidents on paper and cut them apart as indicated on the handouts. Alternatively, you may create your own incidents based on situations unique to the group or your organization. Prepare two large balloons for each team. Place one folded set of Roles inside one balloon and one folded set of Incidents inside the second balloon and inflate the balloons. Select and post the questions you want the groups to address during the session. You should practice the balloon “trick” before the session as well.

Process

1. Introduce the activity and its goals.

2. Demonstrate the “magic balloon trick” by piercing a balloon using a needle without bursting it. Challenge the participants by asking them whether or not they can pierce an inflated balloon with a needle without bursting it. If someone says yes, ask him or her to keep the secret for now. Allow some participants to try piercing the extra balloons with the needle.

3. Invite someone who claims to know the trick to demonstrate it or demonstrate it yourself. State that the secret will be shared at the end of the session (see Insider’s Tips).

4. Introduce the concept of the importance of values at work and invite participants to share the core values of their companies or some of their views regarding the topic. You could start by saying that handling value dilemmas in life sometimes brings up issues that are very difficult and sensitive, similar to piercing an inflated balloon without bursting it!

5. Ask participants to walk to the basket of balloons you have prepared before the session and pick up out one balloon each.

6. Tell them to inflate their balloons. While the participants are engaged in this activity, state that the size of the balloon indicates the level of confidence of the person! Remind them that too much of anything, including confidence, may not be always good! If someone bursts a balloon give him or her another balloon of the same color or number.

7. Ask participants to write short phrases on their balloons related to the issue of living by values and to base the comments on their experience. Share some examples such as difficult choices between rules and compassion, honesty and integrity, fairness and seeing both sides, or other examples. Encourage several participants to share some examples.

8. Ask the participants to form groups based on the color of their balloons (or number written on the balloon) and sit together in small groups, selecting a chairperson to represent each group.

9. Distribute the “Roles” balloons to each group. Tell the groups to burst their balloons and to select one role at random. Request that participants choose the white roles first. Those who do not receive a white role will select the colored paper and play a member role.

10. Explain the roles to the participants and encourage the chairperson of each small group to take over.

11. Ask the participants to introduce themselves to the small groups by sharing their views about values reflected in the words they have written on their balloons. Once everyone has been introduced, encourage all the participants to burst their balloons. Allow about 5 minutes for this step.

12. Give the “Incident” balloons to the chairperson in each group. The groups must burst the balloon to select the incidents. Announce the number of incidents the groups will address (generally, four to six each).

13. Present the flip chart or slide listing the questions you would like the groups to address during their discussion.

14. Tell the groups they have about 40 minutes to discuss the Incidents they selected. Note that they should attempt to come to agreement on how they would deal with each chosen value dilemma. Tell them when you have started the timed period.

15. At the end of the timed period, ask a spokesperson from each group to shares the group’s views and highlights of their discussion. You may encourage further discussion by asking additional questions or by encouraging members of other groups to ask questions.

16. Bring closure by asking:

- How were these value dilemmas and conflicts related to those you experience at work?

- How do values affect decisions and problem solving at work?

- How has this activity changed your awareness of value dilemmas?

- What is a leader’s responsibility regarding an organization’s values?

- What is the most important learning you take away today?

17. Summarize the activity by summing up the learning from each group. At this point, you may conclude with the following points regarding handling value dilemmas at work:

- Handling “black and white” value dilemmas is easy, since one can decide decisively what is “good or bad” or “right or wrong” for the company and the people.

- It is more difficult to resolve a dilemma when you have to choose between two situations that may be equally right or the solution equally appealing.

- The most difficult situations are when you are caught between two equally problematic choices.

- Often there are opportunities to solve even the difficult value dilemmas without compromising one’s personal values or the core values of the organizations, through open-minded thinking and creative solutions. Refer to some of the solutions discovered by the groups as examples.

InSider’s Tips

- The intention is to create some fun and excitement in the room with the intermittent sound of bursting balloons.

- The tips for piercing a balloon without bursting it require that you prepare a balloon in advance by sticking transparent plastic tape in one spot and then putting the pin through that spot. You should also lubricate the pin in advance. In addition, make sure that the needle is sharp and thin and pierces the balloon in a spot where the surface is not stretched, usually at the base.

- This activity can be done with any number of groups of five to seven participants each. If there are more than five groups, you might require additional co-facilitators to ensure adequate support to the groups.

- To shorten the activity, Steps 6 and 11 may be eliminated and members may be encouraged to burst their balloons to celebrate their success when they finish presenting their group views.

- Participants usually are able to come up with very creative solutions to solve the value dilemmas, without compromising their positive values. For example, in the “Friendship Dilemma” incident, values such as “performance” and “honesty” are in conflict with “concern for the people.” One of the most popular solutions to this situation is to help the employees to solve their financial problem through some other methods, such as arranging an interest-free loan, rather than by providing a bonus they do not deserve.

- Some of the values that seem to be in conflict in the incidents are provided as a sample handout. Prepare yourself by generating a set of alternative solutions before you begin the workshop. Normally, each alternative will have some advantages and disadvantages, and the final choice of participants is a matter of values rather than a rational decision.

Sample Incidents in Conflict

| Incidents | Some of the Values in Conflict |

| Friendship Dilemma | Performance, honesty, and integrity vs. friendship, concern for people |

| Caught in Between | Accountability and ownership vs. externalization and blaming |

| Never at Desk | Task vs. people |

| The Indispensable Man | Experience vs. expertise |

| Time Attendance | Fairness vs. need for protecting oneself |

| Safety Business | Concern for the task vs. concern for safety of people |

| Medical Issue | Concern for people vs. honesty |

| Friendly Vendor | Confidentiality and professional ethics vs. friendship |

| Bureaucracy | Flexibility/customer friendliness vs. bureaucracy/risk avoidance |

| Task Master | Task vs. people |

Roles

Incidents

A set of ten incidents is provided here. Modify the incidents for your groups or add new incidents as required. Select four to six of the incidents depending on the time available and group size. Copy and cut them apart to put inside a balloon.

Friendship Dilemma

It is the end of the year and you as the team leader have to ensure that your staff are appraised and given performance ratings. You are aware that the top management has announced a performance bonus for the employees rated as “4” and “5” on the five-point performance rating scale used by the company. Employees who are rated below 4 on performance will not be eligible for the bonus.

Ms. X has been working with you for more than ten years. Unfortunately, she has not been able to perform very well this year due to some family issues. She was also quite disturbed due to some persistent health problems faced by her spouse. Your internal customers have recently complained to you about the poor service they are receiving from her. You have spoken to her on a few occasions throughout the year, but she was unable to improve her performance. She has come to see you today to plead with you to rate her “4,” not “3,” as she is going through some financial problems. You have known her well for a long time and have interacted with her family outside the office on many social occasions. What will you do?

Caught in Between

You are a contract administrator in the IT department. Timely renewal of contracts is one of your key performance indicators agreed upon for the year with your boss.

Five months ago you requested that the procurement department renew a contract. After a month, the procurement department informed you that another vendor claimed that they are the newly appointed representative for the product for the region and therefore you cannot renew the contract with the existing vendor. It took many weeks for you to clarify this issue with the two vendors and the legal, procurement, and finance departments. However, in the meantime the new vendor settled the issue with your contractor and withdrew the claim. Unfortunately, your assistant handling this case went on his annual leave and it took some time for you to follow up on this. Last week, the final contract was sent to the CEO for signature two months after expiring. The CEO was furious to see that the company was using software without a proper contract in place and asked you to explain why this happened. He stated that it is against the company values and policies to treat a vendor like this. You honestly felt that it was not your fault and that many others had contributed to this issue. The CEO has called you, the head of the procurement department, and your boss to seek an explanation. What will be your stand in the meeting? Why?

Never at Desk

Ms. X often arrives late and she disappears from her desk for lengthy periods of time. Friendly attempts as well as serious counseling have not worked. Ms. X told you that she has a migraine problem as well as an ongoing family problem. She is a fast learner and has full capability of becoming a high performer, but unfortunately she is not able to focus on work. You honestly wish to coach and help Ms. X to improve her performance. Another employee in your section, Mr. Y, who is over-burdened, came to you and complained that the work distribution is not fair in the team. Mr. Y has been working overtime. He told you that his family is requesting him to leave the company and take a job in another company if the situation continues. He is seeking your permission to go to higher authorities to resolve this situation. How will you approach this situation?

The Indispensable Man

You are the IT manager of the company. Mr. X has been working with your department for the last ten years. He has developed good relationships with you and with many other people in the company. Recently, you have received many complaints from your internal customers that Mr. X is arrogant, careless, and not friendly to the customers. You have assigned many young and well-trained IT employees to work with him, but he insists that they are not capable of taking over his role fully as he is handling more complex IT systems. Last month Mr. X took a long leave, and a young employee who was a recent graduate in IT was asked to stand by. One of your customers came to you and shared with you that the service is much better now with the young employee being there. You also heard that the young employee is a wizard when it comes to diagnosing and solving IT issues. You were surprised. What will you do?

Time Attendance

Mr. X, a young engineer, was coming late to the office and leaving early. You issued him a warning notice. After this the employee started coming on time and stopped leaving early. However, you have noticed that in between he is not present in the office. When confronted, he stated that he is too busy with various meetings with the customers. However, the customers were complaining about this employee and his non-availability. You are aware that Mr. X was appointed based on the recommendation of the CEO of the company as a favor to one of his close family friends. The other two members of your team have come to you demanding a fair distribution of work among the team members. They felt that it is unfair for you to allow one member of the team to shirk work and overloaded others. What will you do?

Safety Business

You were in the middle of a very important meeting on the fifteenth floor of your corporate office. Your guests had indicated that they had to finish the meeting in the next 5 minutes, as they had another meeting to attend. You are keen to thrash out some key issues and gain some agreements from your guests within the remaining five minutes. While you were discussing these issues, you were surprised to find a worker cleaning the windows of your meeting room from the outside without wearing a helmet. You noticed also that he had not fastened his safety belts properly. What will you do?

Medical Issue

Mr. Y has been working with you for the last seven years. Unfortunately, he has been diagnosed with a medical condition requiring surgery. He is requesting a long leave, beyond what is allowed under the company’s medical and leave policies. He shared that going on leave without salary is going to be very difficult for him. In addition to the medical leave, he would like you to grant him a week away from the office unofficially, without any leave application. He promised that he can do some work while he is in the hospital. You feel very much inclined to help him. However, you are also concerned about questions from higher authorities, as it is against the policy of the company. What will you do?

Friendly Vendor

One of your old friends now working with an engineering company contacted you after a long time and invited you for dinner. He convinced you that his company can be a valuable supplier to your company. You helped him to register with the procurement department of your company and also to be short-listed as a possible vendor for an upcoming project. However, the evaluation committee selected another vendor. Your friend was upset with you and requested you to reveal who was given the contract and why. What do you do next?

Bureaucracy

You are working in a bank that has listed “non-bureaucratic way of working” as one of its core values. Five years ago, the bank had simple forms and processes for its mortgage customers. However, the mortgage department has been revising those forms based on the problems and legal issues they have faced over a period of time. Currently, the bank has a lengthy mortgage application form, which requires the customer to sign in fourteen places. You have been working in the customer service section for many years and have seen many customers become furious about the lengthy process and complicated application forms. Recently, you have been transferred to the mortgage section and were given the task to review the forms. You wanted to simplify the forms and the process, but experienced colleagues in the mortgage section cautioned you, citing the legal problems they have faced in the past due to the use of “simple” forms. What will be your approach?

Task Master

You are the administration manager in a bank. Mr. X who had spent eight years in the army, has recently joined your department as your assistant manager. You observed that Mr. X is a talented administrator and highly experienced at handling various administrative issues. He is a hard worker, high performer, and a tough task master. However, the culture of your company is very different from that of the army, which is usually a “command and control” culture. Your company has a more participative style of management. The team members have complained to you about the dictatorial approach of Mr. X. You have tried to counsel Mr. X and persuade him to change his style. However, Mr. X refuses to buy in, as he strongly believed that his style is the best way to get work out of people. You also observed that some of your employees have started working harder recently, as they were under pressure from Mr. X. In the meantime, one of your team members who is a low performer came to you and stated that he is resigning, as Mr. X is putting unreasonable demands on him. What will you do?

Questions to Address

Sample questions for the groups to address during the discussions and while presenting the groups’ views are listed below. Modify the questions to suit your groups or add new questions as required. Select three to five questions and present them to the groups during the briefing stage.

- Share your group’s decisions regarding each situation and explain the rationale.

- What disagreements occurred among the group members regarding their choices?

- Briefly summarize the views of group members.

- What values seemed to underlie the group’s final decision?

- How did you feel when someone agreed/disagreed with your values?

- Do you think that the similarities in team members’ values help decision making at work? Why?

- What is the impact of having similar values on team work?

- Is “shared values” among the team members good for organizations? Under what circumstances could it become a threat to an organization?

- Is there any right or wrong or black or white solutions to value issues? How do you handle shades of gray?

1Lisa Rike brings over twenty years of experience in the adult learning and development field. Her experience as an instructional designer and facilitator spans multiple topics such as different aspects in leadership skills and team development, interpersonal and behavioral style training, train-the-trainer, communication, coaching, and presentation/facilitation skills. Lisa consults to Fortune 500 companies as well to as small and mid-size organizations. She has designed and facilitated leadership and staff development initiatives that range in scope from improving team performance to permeating company culture to bring about improved business results across organizations.

Lisa Rike

853 West Oak Street

Zionsville, IN 46077

(317) 727.6520

Email: [email protected] or [email protected]

Website: www.etindy.com

ASTD Chapter: Central Indiana

2Barbara Crockett is an independent contractor focused on improving the business and leadership skills of individuals by designing and delivering learning solutions. She is an associate instructor in the Maryville University School of Business School, facilitator for Selsius Corporate and Career Training in Belleville, Illinois, and facilitator for the Center for Financial Training in St. Louis, Missouri. Her personal philosophy of learning is to “make it active” and to always include the question, “How can I apply this to my work/world?”

Barbara Crockett

9857 Berwick Drive

St. Louis, MO 63123

(314) 313.8575

Email: [email protected]

ASTD Chapter: St. Louis Metropolitan

3Mel Schnapper is an international consultant (native Washingtonian), now working in Lesotho. He has worked in over twenty countries doing organization development, business process analysis, team building, and some traditional personnel work. Mel recently published a book on performance metrics, Value-Based Metrics for Improving Results, with a methodology for measuring any kind of performance, especially when people, even colleagues, say “You can’t measure it!” He has an extensive career in corporate America with companies such as Quaker Oats, Chicago Board Options Exchange, AT&T, and American Express. Although he prefers the exotic environments outside the U.S., he does miss D.C. now and then and comes back about twice a year.

Mel Schnapper

Meidoornplein 18, 1112 EK

Diemen, Holland

Phone: 31–2040205851

Email: [email protected]

Website:www.schnapper.com

ASTD Chapter: Metro Washington, D.C.

4Lisa Rike provides over twenty years of experience in the adult learning and development field. Her experience as an instructional designer and facilitator spans multiple topics, such as different aspects in leadership skills and team development, interpersonal and behavioral style training, train-the-trainer, communication, coaching, and presentation/facilitation skills. Lisa is a consultant to Fortune 500 companies as well as to small and mid-size organizations. She has designed and facilitated leadership and staff development initiatives that range in scope from improving team performance to permeating company culture to bring about improved business results across organizations.

Lisa Rike

853 West Oak Street

Zionsville, IN 46077

(317) 727.6520

Email: [email protected] or [email protected]

Website: www.etindy.com

ASTD Chapter: Central Indiana

5Cindy Phillips, Ph.D., is the president of Leadership4Change, LLC. She is a consultant and educator with expertise in organization development, leadership development, team building, and change management. With several years of management experience in the technology sector, she specializes in developing and implementing change initiatives, along with coaching and strengthening leaders to guide those efforts. She has worked with a diverse range and size of client systems, including Alcoa, Bosch, Booz Allen Hamilton, Capital Blue Cross, the Department of Energy, Harley-Davidson, Sodexo, SAP, Little League Baseball, and Wells Fargo. She completed a Ph.D. in organization development at the Fielding Graduate University, an MBA from St. Joseph’s University, and a B.S. in finance/computer science from Towson University. She is an ICF-certified executive coach and a certified action learning coach.

Cindy Phillips, Ph.D.

2436 Stone Heath Drive

Lancaster, PA 17601

(717) 572.6755

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.leadership4change.com

ASTD Chapter: Central Pennsylvania

6Jeff Furman has extensive experience as both a PMP instructor and an IT project manager. He has managed many large IT projects for Fortune 100 companies in the New York metropolitan area. He has trained hundreds of project managers and helped them become PMP certified. He has also trained many instructors and helped them become certified technical trainers. He authored The Project Management Answer Book, published by Management Concepts, a book that will help project managers learn the cutting-edge skills to become more efficient on their projects and to pass the PMP exam.

Jeff Furman

123 Willow Avenue

Hoboken, NJ 07030

(201) 310.7997

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.Jeff-Furman.com

ASTD Chapter: New York Metro

7P. Sethu Madhavan, Ph.D., is an established HRD expert working with the Tawazun at Abu Dhabi. Earlier he worked with Ernst and Young, Larsen and Tubro, Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operation, Indian Institute of Management, the Centre for Organization Development, and Academy of HRD (India). He has rendered training and consulting services to many leading companies covering many sectors. He has co-authored a book and has many publications, case studies, psychological tests, and survey instruments to his credit. He has served as the editor of journals and as a member of the board of professional bodies. Currently he is a member of the executive council of the National Academy of Psychology (NOAP). He has spoken regularly at HR events in Europe and Asia.

P. Sethu Madhavan, Ph.D.

P.O. Box 908

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

+971–50–6673021

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.drsethu.com

ASTD Chapter: International

8Yehya M. Al Marzouqi, Ph.D., is a leading HRD expert, speaker, and trainer, working with the Tawazun at Abu Dhabi in a senior and strategic role related to human capital. Prior to joining Offset, he had worked in Abu Dhabi Company for Onshore Oil Operation (ADCO) since 1992. During his career he had led various initiatives such as business process re-engineering, establishing personal development processes and plans, succession planning, establishing assessment centers, implementing competency-based training, establishing training centers, implementing e-learning, 360-degree feedback initiatives, and so forth. Yehya has also facilitated large scale change initiatives such as articulating and establishing organizational values and conducted many training workshops.

Yehya M. Al Marzouqi, Ph.D.

P.O. Box 908

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

+971–50–6419700

Email: [email protected]

Website: [email protected]

ASTD Chapter: International