Chapter 8. Risk Aversion and Security Topologies

This chapter uses information that was presented in Chapter 4, "Putting It All Together: Threats and Security Equipment,” along with the results from surveys completed in both Chapter 5, "Policy, Personnel, and Equipment as Security Enablers,” and Chapter 7, "Engaging the Corporation: Management and Employees.” The surveys from both chapters can aid organizations in deriving a security topology model that is both relevant and viable.

This chapter covers the following topics:

• Risk aversion

• Risk-aversion quotient

• Security modeling

• Diminishing returns

Risk Aversion

Using explanations and examples, this section explores the following topics:

• The notion of risk aversion

• Determining risk tolerance

• What assets to protect

• Short-term and long-term risks

The Notion of Risk Aversion

Risk aversion is highly subjective. One person’s high-risk situation is another’s light adventure. For example, driving slowly through a tough inner-city neighborhood late at night with the car windows down and the stereo pumping out classical music might appear to be foolhardy, but depending on the viewpoint of those assessing the situation, it could be seen as intensely risky or simply engaging in light comedic adventure. Whether the discussion embodies an individual or an organization, the ability to tolerate risk is wholly personal to that one entity.

Certain organizations are greater targets than others. Companies that engage in activities that might be construed as being less than beneficial to every group in society could find themselves the victims of targeted attacks, whereas smaller, less visible companies might only need to defend against random attacks and potentially disgruntled associates. Regardless of a corporation’s visibility, or lack thereof, the potential randomness of attacks implies that every organization is, at certain levels, equally vulnerable.

The ability of corporations to tolerate risk can never be assumed. Whichever route an organization takes to determine its level of tolerance, risk aversion will continue to be an intensely subjective matter.

Determining Risk Tolerance

Whether it concerns an individual or a corporation, risk tolerance is highly personal. One argument says that size, or even type, of business does not necessarily have a bearing on the level of risk a corporation is willing to tolerate. To resolve this argument, an organization attempts to determine its logical risk tolerance level. It can conduct studies to establish the amount of risk it can afford to take on and then logically structure the company based on the findings of the analytical report. But in the end, studies can only make suggestions; logical analyses can only focus on black-and-white issues.

Surveys found at the end of Chapters 5 and 7 can aid executive managers in developing a greater awareness of their true aversion to threats. The surveys use a process that combines logical situational analysis with a subjective read of the corporation’s needs. While the tool leads the respondent to a model that can be implemented, it also attempts to engage executive management in a discussion that can help to succinctly assess the organization’s tolerance for risk.

Organizations should take a long-term perspective of risk tolerance and develop a formal review process to ensure that risk tolerance reviews are mandated—and occur at prescribed times. While reviews should ensure that risk tolerance levels are not changed too frequently, or even needlessly, any review process should allow for situational reviews to occur quickly in the event of major structural events, such as change of ownership or other significant happenings.

Which Assets to Protect

Assets are typically viewed as constituting physical goods or intellectual property. But depending on the organization, an asset can also be its operations or, more specifically, its undisturbed operability. An organization, such as a selling forum website whose business is conducted almost completely in the open, could be damaged if its services were severely disrupted. While the website must retain and effectively secure private data, its customers demand reliability, requiring a market that is always open for business. Uninterrupted operability is at the crux of its business.

Short-Term and Long-Term Risks

Risk can be viewed in the near term, as organizations attempt to ascertain damage that could occur if preventative measures were not put in place. Some examples of short-term risks are as follows:

• Damaged and unavailable equipment

• Interrupted sales and service revenue

• Bottlenecked supply chains and production lines

• IT overtime payroll costs to mend immediate situations

When a long-term approach is assumed, security initiative risks consider the following items:

• New equipment and its corresponding upgrade path

• Preliminary and ongoing training

• Damaged customer relationships

• Lessened revenue stream

• Loss of trust

• Reliability

• Pertinent other intangible components

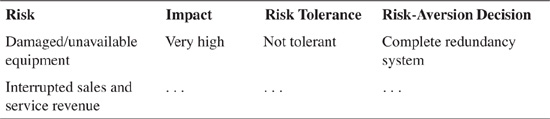

Tables 8-1 and 8-2 show how low-risk-tolerant and high-risk-tolerant organizations, respectively, can determine how short- and long-term events could affect a corporation’s tolerance for risk. Because events that could occur are inherently individual, every corporation should determine its own list of relevant events. Each table has one sample line and a few of the possible risks to show an example of how to get started. An organization could list all the risks in such a table to determine how short- and long-term events could affect a corporation’s tolerance for risk.

Risk-Aversion Quotient

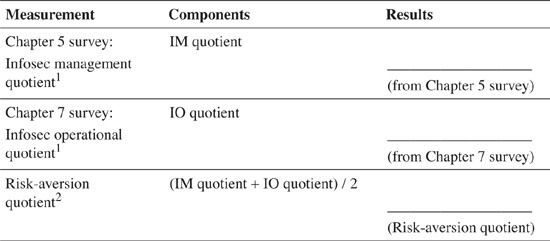

The surveys presented in Chapters 5 and 7 are designed to quantify the subjective elements that are an inescapable component of business structures and operating systems. These surveys produce an Infosec management (IM) quotient and an Infosec operational (IO) quotient that are referenced in this section covering the risk-aversion quotient.

This section explores the following topics:

• Calculating the risk-aversion quotient

• Risk-aversion quotient and risk tolerance

• Using the charts

Calculating the Risk-Aversion Quotient

Use the following formula to calculate the risk-aversion (RA) quotient:

To calculate the RA quotient, populate the Results column in Table 8-3 with the reserved results from the surveys found in Chapters 5 and 7.

The following is an example of survey results from a hypothetical organization. Because individual results can vary, average figures were used in the following example to determine a company’s risk-aversion quotient:

IM quotient (from Chapter 5 survey): 74%

IO quotient (from Chapter 7 survey): 67%

RA quotient = (IM quotient + IO quotient) / 2

RA quotient = (74 + 67) / 2

RA quotient ![]() 71%

71%

Risk-Aversion Quotient and Risk Tolerance

When the risk-aversion quotient has been determined, the level of risk tolerance can be identified, as illustrated in Table 8-4.

In the previous example, the risk-aversion quotient was determined to be 71%. Using Table 8-4, the company is shown to have a medium-low risk tolerance.

Using the Charts

Similar to all charts, the risk-aversion quotient and risk tolerance equivalency scale should be used as guides rather than an unequivocal path that an organization should follow. While a company can use the IM and IO surveys to determine its own tolerance level, as shown in Table 8-4, survey respondents will likely be executives and managers culled from a wide cross section of an organization. While one hopes for independent responses, a certain percentage of respondents can respond with particular agendas in mind. The security steering committee or executive management must take the information derived from the surveys into consideration and, if necessary, choose a model that best reflects its tolerance for, or aversion to, risk.

The surveys build consensus and can serve a multitude of purposes, including the ability to shed necessary light on oft-forgotten or overlooked areas of an operation that can leave an organization unduly vulnerable. The mean scores should help to serve as a guide in representing the needs of an organization’s managers, but the scores should not necessarily be the determining factor in an organization’s required security posture.

Security Modeling

The task of determining which topology to implement on a network can be challenging, even after IM and IO surveys have been completed. While the surveys can aid organizations in determining their risk tolerance level, as shown earlier in Table 8-4, this section advances the process by using the ranking to offer various equipment choices. But one size rarely fits all, and a range of possible options is presented for each of the varying category types.

This section discusses the following topics:

• Topology standards

• One size rarely fits all

• Security throughout the network

Topology Standards

The discussion in Chapter 4 centered on the following three topology standards:

• Basic

• Modest

• Comprehensive

Table 8-5 illustrates how the risk-aversion quotient translates to a security model that can be adopted. Note that for some tolerance categories, a range of models apply.

The security models are covered in more detail in Chapter 4. In the previous example in this chapter, the risk-aversion quotient was determined to be 71% and the risk tolerance was medium-low. Using the risk tolerance level, the security model could be determined as being comprehensive or modest.

One Size Rarely Fits All

Blending security requirements and specific models is not an exact science. As evidenced earlier, subjective influences can be incorporated into the process to ensure that an organization’s needs are fully met.

Table 8-5 reflects the individual nature of security posture requirements. One size cannot fit all; two companies operating in the same field, with like structures and similar databases, can require different security postures. Whether it is the strategic value of information that is being protected or the physical operability of a company that is of paramount importance, security requirements will inevitably be singularly unique.

A modest model does not necessarily come in one size. It can be basic or comprehensive, or a blend of both. The equipment that is required should be wholly dependent on the needs of the organization, rather than a predetermined model. Cost is fully explored in Chapter 9, "Return on Prevention: Investing in Capital Assets,” when the analysis considers total cost of ownership (TCO) and return on prevention (ROP). At this point in the discussion, the most logical level—basic, modest, or comprehensive—should be chosen.

Also, within organizations, markedly different perspectives can exist. An alarmist might state that a fully redundant system is needed to ensure that an organization is as secure as possible. But depending on the business or the industry in which an organization is involved, a fully redundant system might not be necessary. It might be desired, but after a thorough cost analysis, the relative cost of protection might outweigh the risk.

The mandate of this chapter and the next is to help determine the suitability of a chosen security level and to ensure that equipment specific to that model delivers the requisite protection within a sound TCO and ROP analysis.

Security Throughout the Network

Security has been traditionally focused on protecting the organization at the perimeter by keeping out potential intruders, whether they are cyber or physical. The term crunchy on the outside refers to strong perimeter protection. As explored in Chapter 3, "Security Technology and Related Equipment,” however, firms are beginning to become crunchy on the inside as well, with firewalls and similar protective devices becoming more frequently installed between departments. A finance department, as an example, can only ensure the verity of its documentation when it can assure the board of the sanctity of its data. The need for individual departmental protection, possibly only at a basic level, should not be underestimated, particularly as an organization grows.

Modest Security Scenario for an SMB

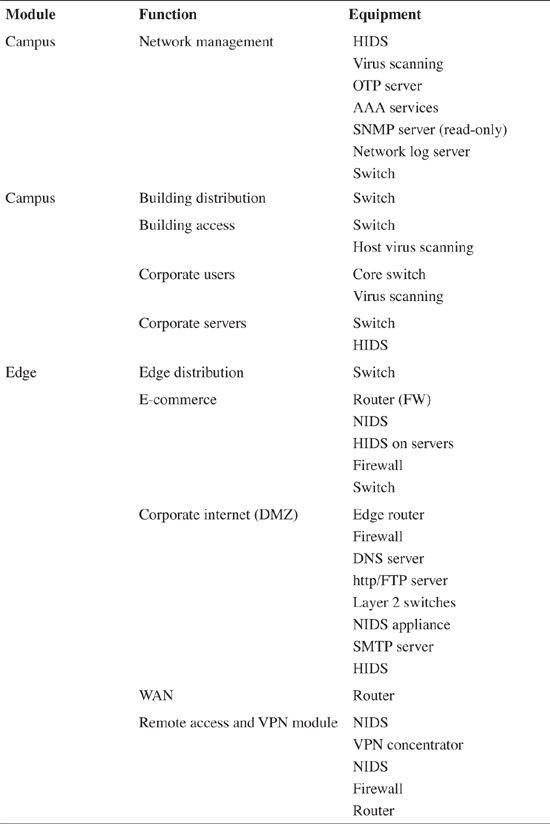

When a model has been chosen, as explained in Chapter 4, the system administrator or IT manager can choose from a list of components to develop the required infrastructure. The art of developing network topology can be challenging. Most IT managers acknowledge the subjective nature of their craft—what might be considered a fundamental piece of equipment to one IT manager could be viewed as extravagant to another. For the purposes of continuity, Table 8-6 represents an SMB’s shopping list for the modest model, and the shaded items are considered essential components.

The security topology for an SMB is formally represented by Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. SMB Security Topology (Source: "SAFE: Extending the Security Blueprint to Small, Midsize, and Remote-User Networks")

Note that in Table 8-6, equipment for the service provider (SP) edge module was not provided, because the SP typically provides required equipment.

Managing Requirements

In an ideal world, network layouts are finalized, investment capital is readily available, and infrastructure is fully provisioned. The reality is that most organizations need to build networks over time, as requirements increase and funding attempts to keep in step.

When a model has been chosen, an organization might discover that certain components of the model are already deployed on its network. But regardless of whether equipment is readily available, it is important not to be intimidated by large topology shopping lists. The lists can be adapted to account for a variety of situations, including the recognition that an organization could be in one of three phases: early adoption, growth, or mature phase.

An organization does not need to acquire all equipment at one time; some can be more immediate than others. The life cycle can also vary for different pieces of hardware and software. Typically, the more costly a component, the longer its life cycle, although upgrades will be a continual expense over the life of most products.

Modest Security Scenario for an Enterprise

Table 8-7 provides a topology shopping list for a modest security model, as shown in Figure 8-2, on an enterprise-size network.

Figure 8-2. Modest Security Topology for an Enterprise (Source: "SAFE: A Security Blueprint for Enterprise Networks")

Diminishing Returns

The three security models (basic, modest, and comprehensive) differ markedly in level of protection, but the law of diminishing returns recognizes that as an organization moves from one level to the next, its ability to extract equal value from each significant move begins to diminish. While the organization’s level of protection increases, its most dramatic change occurs when it goes from no security to incorporating a basic model.

Figure 8-3 illustrates the law of diminishing returns as it applies to the security models and expenditures.

A comprehensive model can be desired by many organizations, but depending on the type of business in which a corporation is engaged, this type of model might not be wholly necessary.

The graph line starts to flatten out between moderate and comprehensive, because the functionality that an organization would obtain from an ultra-specialized dedicated appliance might already have been partially addressed by a product that was previously used in the modest or basic model. Another reason for the flattened graph line is that the comprehensive model calls for redundancy, namely, hot-standby equipment that begins to work should the primary equipment fail; it does not necessarily imply that a raft of new functionality will be incorporated onto a network. For example, a comprehensive model would likely call for a virtual carbon copy firewall, identical to the one at the network’s perimeter, to be available should a situation ever render the primary firewall ineffective. While an organization would not realize an immediate benefit from investing in an alternate firewall, should the primary unit fail, the hot standby would be ready to go live. By addressing a company’s fundamental need for uninterrupted operability, the financial benefit of a comprehensive security installation can begin to be derived.

The result is that the comprehensive model requires that a certain level of funding be allocated to hardware-operational contingency planning.

Summary

Risk aversion is unique to every organization, requiring those involved in assessing a corporation’s level of tolerance acknowledge the implications inherent in each security model type.

The topology models presented in Chapter 4, along with the Infosec management quotient from Chapter 5 and the Infosec operational quotient determined in Chapter 7, are brought together in this chapter to aid the reader in determining a security topology for his or her network.

Representative shopping lists are presented for two model types, and the law of diminishing returns is explored as it relates to security investments.

This chapter discussed the following topics:

• Significance of risk aversion

• Developing a risk-aversion quotient

• Security modeling examples

• Relevance of diminishing returns