Focusing DM to Meet Common Organizational Challenges

4.2 Ubiquitous DM Challenges: Complexity, Degree, and Scope

4.3 Objective Assessments of Organizational DM

4.3.1 DM Program Success: Self Assessment

4.3.2 DM Visibility Within the CIO Function

4.3.3 Measurable Data Quality and Responsibility for Data Quality

4.4 Why CIOs Fail to Recognize Needed DM Improvements

4.5 Why it Might be Difficult to Change the Status Quo?

4.1 Chapter Overview

All organizations perform DM activities – the relevant questions are:

1. How critical to organizational success are they?; and

2. How well prepared is the organization to address their DM challenges?

Leveraging data in support of strategy remains a common organizational challenge. Organizations are performing DM poorly. Perhaps more importantly, responsibility for addressing the gaps is at best ill-defined, and at worst, an unrecognized challenge. Objective measures of the “health” of DM practices worldwide presented below indicate that the typical organization is not able to leverage data in support of strategy.

4.2 Ubiquitous DM Challenges: Complexity, Degree, and Scope

DM as an industry has not been much studied.1 There are few formal measures. Unlike software engineering, even relatively simplistic order of magnitude sizing calculations cannot be made reliably (McCabe 1976). When it is clear that an organization can benefit from effective and efficient (or what are called, ‘advantageous’ DM practices), the next evaluative step is to determine the DM challenge characteristics.

An organization’s relative data challenge ‘size’ is a question of degree and complexity (Figure 4.1) within a defined scope. Organizations demonstrate that they believe that by increasing their DM proficiencies, their use of data to support strategy will improve. DM value can be readily concretized as increases in the number of data aggregators and organizations selling training on how to access, for example, Walmart’s Retail Link® portal.2

Perhaps all the talk of the impending data deluge has them taking note (Economist 2010). DM was projected to be a $4 billion dollar annual market in 2012 (Bernstein and Haas 2008) and US President Obama highlighted DM as a “skill that businesses are looking for right now!” in his 2012 State of the Union message (Obama 2012).

4.2.1 Complexity

Organizational DM complexity can be assessed by subject area. Within subject areas, the data differs, different success levels are achieved, and different time-constraints are imposed on service deliveries but in aggregate it is easier to get a 360° picture within each area. Organizational DM challenges range widely but with no seeming correlation to organizational size. For example, it is possible and useful to develop expertise in the data of the Chemical Industry (CI) but it is generally not terribly complex to understand CI data. It is more complex to understand Wall Street data than CI data but CI data assumes that the human has mastered chemical engineering skills. While math is required and helpful, Wall Street data does not require mastery of skills required for chemical engineering. DM in the health care industry is particularly complex due to interactions among personally identifiable information, sunshine, intellectual property laws, etc.

4.2.2 Degree

Degree plays a role similar to complexity but is an organization/situation dependent characteristic. For example, a small, highly skill-focused organization (for example a medium-sized veterinary practice grossing $3 million annually) can be ‘run’ quite well using a single, integrated software package (the micro-ERP if you will). The more functionality existing in the micro-ERP, the less the DM challenge and the fewer the physical interfaces required.3 The number of required interfaces is almost never zero. There are always specialized devices and systems requiring integration with the micro-ERP. These interfaces often require cumbersome (occasionally manual) data movement.

4.2.3 Scope

DM scope cannot, by definition, be encapsulated within one organizational area. The need for DM across the databases and systems exists for both the infrastructure and functional areas. DM scope relates to specific activities, work products, and architectural components. DM work products should affect different activities, hence the governance need. For example, you may maintain common data for facilities, staff, organizations, and partner organizations. If these data are to be consistent across all these different application areas, there must be a DM activity maintaining common semantics and data values. Similarly complex interaction can exist between infrastructure and area applications.

Everyone faces data challenges varying in complexity, degree, and scope. Data broadly interacts with business, infrastructure, and IT architectures. The task is to identify data classes within subject areas, and architect/engineer the best data leverage strategy. Without a good understanding of the relative size of the data challenge (degree/complexity for a specific scope) facing your organization, investments in data cannot be justified. Initially, almost all organizations will require some help with their organizational data decisions.

There is a natural tendency to put off the strategic because its immediate accomplishment is not perceived to be critical to the day-to-day organization operations. If strategic DM is ignored too long, the IT systems and databases within the organization degrade, become disorganized, and expensive to maintain. These costs can be sharply contrasted with organizations that understand the strategic nature of metadata practices – developed and employed to accelerate IT development and maintenance/evolution. When data classes are properly managed, the ability to leverage the commonly defined data grows commensurately. Maturing too is interoperability, integration, and data conformity. Databases are fewer, interfaces are decreasing, consistency is increased, and reuse is improving.

4.3 Objective Assessments of Organizational DM

Measures indicate that organizational DM performance has been poor. These include: DM program success; data quality measurements; and subjective DM performance. Organization DM performance is not comprehensive across areas. DM has not been consistently applied. DM programs are seldom assessed for quality and effectiveness. To be both valid and comprehensive, DM program assessments must at least address:

4.3.1 DM Program Success: Self Assessment

The first author participated in a study of DM professionals (1981–2007) that revealed low DM practice maturity levels (Aiken, Gillenson et al. 2011). The survey measured the five DM practice areas according to the five CMM maturity levels (see below and also Figure 5.8 in Chapter 5).

| CMM Levels (Y-axis) | Five DM Practice Areas |

| Initial | Data Program Coordination |

| Repeatable | Operational Data Integration |

| Defined | Data Stewardship |

| Managed | Data Development |

| Optimized | Data Support Operations. |

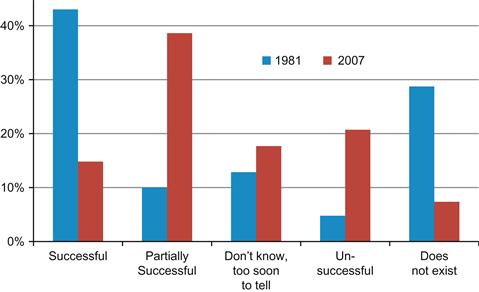

Across these practice areas, the study showed average CMM level was between 2 and 3 – between REPEATABLE and DEFINED. Starkly, across these practices areas no aspect of DM was thoroughly DEFINED. Figure 4.2 indicates low averages, with the typical organization unable to recreate basic DM practices should they become confused. This effectively blocks any self-correction or improvement potential. Subsequent to the 2007 study, the general scores have not improved (in green) and only two organizations (out of 500+) have scored evidence of MANAGED DM practices.

Figure 4.3 illustrates one of the study’s most striking findings – the marked decrease in the profession’s collective assessment of its success – dropping from 43% in 1981 to 15% and the number labeled ‘unsuccessful’ increased from 5% to 21% in 2007 (Aiken, Gillenson et al. 2011).

This collective state-of-the-practice will remain true if the overall industry-wide DM performance remains uniformly low. If one competitor begins to out-perform the rest using better application of DM, the game will change quickly. Recall that industry adoption of RFID tags skyrocketed once retailers went RFID (Williams 2004).

4.3.2 DM Visibility Within the CIO Function

Over the past 25 years the DM group has moved down the reporting chain. As a priority, data has been pushed away from the CIO function.

| 1981 | 2007 |

| 74% reported to the CIO or 1-level down | 43% reported to the CIO or 1- level down |

| 26% reported at least 3-levels down | 57% reported at least 3-levels down |

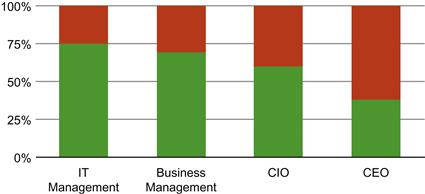

These measures indicate widespread misunderstanding of data’s strategic value. Too few, from CEOs on down, perceive the strategic value of data. Figure 4.4 indicates relative ‘understanding’ as rated by the 2007 survey of data managers. Fully one-quarter of IT managers and more than one-third of CIOs were seen as not understanding the strategic role data plays.

4.3.3 Measurable Data Quality and Responsibility for Data Quality

Much anecdotal evidence documents the costs of poor DM practices including:

• Excessive/unnecessary interfaces. Data quality is inversely proportional to the quantity of interface systems.

• Development delays due to low quality database designs; incomplete and unenforced value domains; inconsistent granularity; precision and data timeliness.

• Prohibitive migrations because of poor data quality, inconsistent semantics, and the data recollections.

• Excessively expensive data warehouse systems that either fail or consume resources well beyond original estimates due to data quality issues.

• Incorrect reporting of business transaction summaries due to ambiguous or outdated operational data.

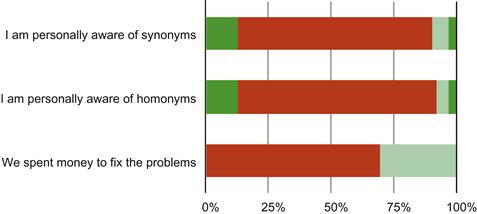

We are unaware of any studies that show that data quality challenges are diminishing – all show the problem as large and growing [see Figure 4.5, (Pipino, Lee et al. 2002), (Kahn, Strong et al. 2002), and (Redman 2008)]. Many measures of data quality costs have been reported – perhaps the most comprehensive case being Larry English’s massive study accumulating more than 100 attributable, poor data quality stories amounting to over $1.2 trillion (English 2009)!

Figure 4.5 Red indicates widespread awareness of data quality issues. From (Aiken, Gillenson et al. 2011)

When researching data quality, two things become apparent. First, there is a fundamental misperception about whose problem data quality really is. When asked, survey after survey of non-IT knowledge workers indicate that data quality is the responsibility of IT, and IT believes that data quality is the responsibility of the business [see for example (Eckerson 2001)]. Second, data quality is not a primary concern for CIOs. Figure 4.6 illustrates that 49% believe IT responsible for data quality but this is not a universally held opinion as evidenced by the categories within the red circle.

“Most think that this function is performed by the technology group – an already overwhelmed group of dedicated individuals who think that data quality is a function managed by the business. Clearly, the responsibility of this … has fallen between the cracks.”

Figure 4.6 Who is responsible for data quality? Source: adapted from (Eckerson 2002)

To summarize the objective data about organizational DM performance:

• Those closest to the DM practices rate their own levels of success low – widely unable to use DEFINED processes and very little evidence of excellence in practice.

• As the distance between DM and the CIO increased and the C-level understanding of data issues dropped.

• The data quality responsibility gap has not been addressed – both IT and the business hope the other is addressing the problem.

The ultimate responsibility for managing data as an asset is ill defined. As organizations rectify this situation with uniform DM practices, they will better cope with:

• Increasing scope and responsibilities.

• Improve the overall CMM levels.

• Improve C-level understanding of data asset leveraging.

• Codified skills and activities.4

4.4 Why CIOs Fail to Recognize Needed DM Improvements

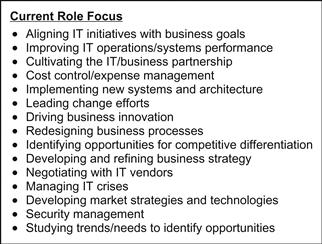

While the cause of this DM failure may seem puzzling at first, the reasons become clearer after examining the advice given to CIOs. Using multiple annual CIO surveys, we created a concept map showing recent priorities. The data came from two sources – surveys of: 1) what CIOs reported as top priorities and 2) what industry experts advised CIOs. Figure 4.7 indicates the coverage of these 48 sources by year (for example – we were only able to locate the 2007 version of the UK CIO Survey results but all years of the Gartner Annual Priorities).

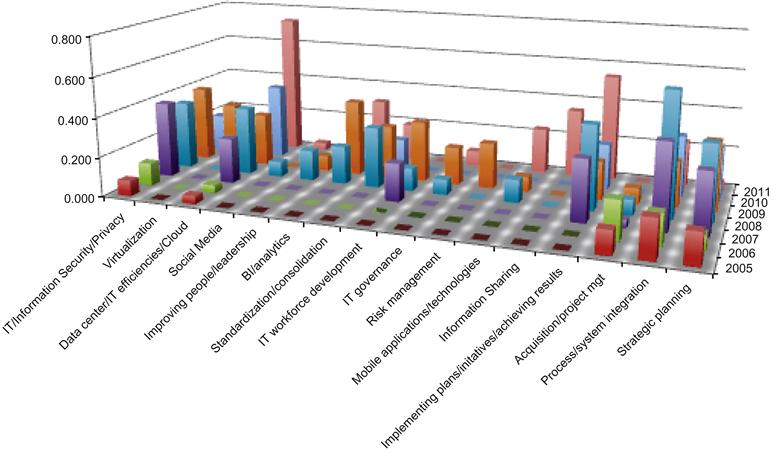

We assessed subjective DM performance data, comparing various priorities that CIOs and influencers of CIOs rated as their top five things to pay attention to – this year – each year for the seven years (2005–2011). The resulting ranks were inverted (i.e. the top ranked concern was given five points, the next ranked concern was given four points, etc.) and grouped by year. Because different years contained different numbers of concerns, we normalized each year’s concerns – dividing by the total observations. Figure 4.8 summarizes this analysis.

Using a three-dimensional viewer, one could observe that IT/Information Security/Privacy has consistently been a top-five concern. The titles demonstrate that, as a CIO priority, little formal attention is paid to DM. There is an absence of DM topics beyond ‘information sharing’ and that only ranked in the top five during the year 2011. Many conversations with current and past CIOs confirm that DM is not on their radars.

Utilizing these sources, Figure 4.9 presents an array of CIO advocated focus areas. Notice that DM did not on make the list. This subjective data forces us a common observation: the CIO function’s distance (conceptually and organizationally) have resulted in losing touch with data-centric details/progress/concerns of data managers. Simply put, DM is not seen as a concern by CIO, or by those who advise them. This leads to one of three conclusions:

1. CIOs think DM is being adequately accomplished in their organizations; or

2. CIOs are unaware of the strategic nature of data; or

3. CIOs are not concerned about how DM is accomplished in their organizations.

We don’t believe that conclusion 3 is true. The answer is a combination of 1 and 2. CIOs have been surprised when reminded of DM’s foundational role in other organizational technology initiatives. Collectively, either they were not data-knowledgeable or they don’t believe that improving their organizational DM performance is important to their success as CIOs.

4.5 Why it Might be Difficult to Change the Status Quo?

A natural tendency is to assume that the CIO function not only takes care of IT but also of data. From a title perspective, one could well argue that these are the logical groups to take on the CDO responsibilities. Indeed, many organizations are defining CDO roles that report to the CIO. There are two challenges with this arrangement: first, technology project implementation depends on data operating on a programmatic basis. Secondly, today’s CIOs are most often really Chief of Information Technology or perhaps CTOs, in addition to being the Chiefs of Information. CIO concerns indicate that DM is either way down on the CIO’s priority list or has fallen off altogether. In the prototypical organization, there would be no CIO, and the CDO would play a role in determining the information delivery agenda of the CTO. Solutions to this must come from universities, business information systems development practices, DM professionals and/or their professional associations, or a laser-like focus on DM by the CIO.

4.5.1 University DM Education

Studies from DAMA International indicate that DM professionals spent 10 years in other areas of IT before understanding data leveraging (Perez 2006). We need to find ways to shorten the process so that professionals realize data’s important earlier in their careers. Recall that non-IT students learn little about systems, code, technology, etc. (but virtually all learn Microsoft’s Excel). Organizations do not know that data is an asset and IT thinks that the answer to data management questions is technology. Curricula are in need of updating.

4.5.2 IT System Development Practices

New systems projects include the natural tendency to create new databases. Alternatively, interaction with an existing database is accomplished using interfaces. As ‘new’ development is preferred to ‘maintenance’ work, new systems are perceived as more ‘exciting’ and preferred. A prime reason existing databases are unable to serve multiple applications is that they have brittle designs – supporting tightly coupled programs/data and creating more data silos. It is natural to not want to slow systems development to prevent the creation of a new silo:

• The existing database that serves a specific function likely has to be redesigned. Who would pay for it?

• The existing system has to be modified to work with the revised database. Who would pay for that?

As a consequence, data silos grow constantly. So too do the data integration, interoperability, and non-redundancy challenges. Over time this degrades into a downward spiral increasingly reducing operational efficiencies. Organizational entropy is directly related to the quantity of data interfaces.

4.5.3 DM Professionals

Complicating the progress, most professionals are unaware of the definitional work done to date. The DAMA Data Management Body of Knowledge is an important first step in the right direction (DAMA-International 2009). For the first time: defined skill sets; methods; standard work product specifications; tool sets; certification;5 and much more exists. These and related efforts need to become better known, in the same manner that project management concepts such as work breakdown structures and Gantt charts are now familiar to the larger knowledge worker community.

4.6 Chapter Summary

While all organizations have data challenges of varying shapes and sizes, the DM status quo is simply this:

• For some very good reasons, CIOs have not see DM as a priority.

• Comprehensive, high quality DM must be developed and delivered outside of IT.

• Universities and training programs need to develop and implement DM courses and educational programs.

• DM professionals and their supporting professional organizations must provide more in-depth DM training, workshop and seminar materials.

1For example data topics comprise around under 7% of a major research keyword index – this is disproportionately low and constrains research opportunities (see http://www.acm.org/about/class/1998)

2Retail Link® is a registered trademark of WalMart Stores, Inc. – see also for example:http://datablueprint.comhttp://lexisnexis.com. http://www.locationawhere.com/19/12/2009/companies/awhere-inc. http://www.acceleratedanalytics.com/blogcontent/making-the-most-of-retail-link-data.html. http://www.8thandwalton.com/courses (all accessed 1/17/2013)

3Recall that interface represents a sunk development cost and an ongoing maintenance expense.

4At a recent professional gathering more than 300 titles were used by 1,200 attendees.

5As of Q1 2013, more than 1,000 individuals worldwide have passed the CDMP examination and the phrase “CDMP Preferred” is seen more commonly on various job posting, including the one provided in Chapter 6.