1

Film Development and the Producers

Well, I think like anything [producing], it’s just storytelling. I think at the end of the day what I love most about producing is helping hold the vision for the story and making sure the right people creatively are associated with the project to create that vision.

Stephan Schultze, Producer, Executive Director of Cinematic Arts, Liberty University

The Producer’s Job

The Producer’s Job

The producer of any media is, or should be, a leader. She is the one person on a project who is responsible for everything—the process, the budget, the people, and ultimately the final product—whether it be feature film, documentary, mobile content, or live events. Notice I don’t say the producer does everything, because a good producer knows how to delegate. The producer definitely has to have the ultimate vision for what the project needs to be and also the ability to communicate that vision to the director. A producer is the type of person who is highly self-motivated, who can take a great idea and transform it into a great film or show. A producer will know how to navigate the film development process and get people interested in funding a project. Being a producer is seeing all the possibilities of a project and having the ability to put together the right people and elements that will make it work. What makes a good producer great is a combination of many factors:

- Knows how to handle people. A producer not only deals with paperwork such as budgets and cost reports but also must lead a large group of people in often stressful situations. If someone does not perform well, the unit production manager (UPM) or producer may need to handle the situation and either help the person improve or, if necessary, fire that person.

- Able to handle confrontation and personality conflicts. The business of making a film or any show involves a large group of people working extremely closely for long hours. Conflicts are bound to arise, and do.

- Able to handle a large volume of details and people all at once.

- Able to handle stress.

- Good at motivating people, able to get them to work in tough situations.

- Knows what makes a good script, and how to get the story on the screen.

- Good at rewriting, as is usually necessary on any project.

- Able to match a script with the director who would be best for that project. I once produced a short film about the Holocaust. I had two very able directors up for the position. My final decision was based on the sensitivity and maturity of one of the directors, even though the other director had better technique.

- Able to deal with prima donnas. Unfortunately, the industry is full of them, and it is hard to see them coming. You may find a prima donna in the form of a director of photography (DP) or even in a production assistant (PA). A good producer knows how to handle these kinds of people.

- Able to fire people. Ability to hire the right people for the right positions and fire the ones who don’t work out.

- Knows how to delegate. While it is sometimes good for a producer to be hands-on, a good producer gets a lot done in a short period of time by knowing what should be delegated.

The producer generally is the final authority of a project, but there are some exceptions. For instance, in some cases the producer of a film is the final creative authority, even over the director. However, this is not always true. You may use a well-established director with much power but have a producer who is just starting out. In this case the director would have greater creative authority.

The Executive Producer

The Executive Producer

There are many different kinds of producers. In single-camera production the executive producer (EP) is most likely the person who puts a project together. This person creates a “package” that may include certain stars and a director. In other productions the EP may be the person who is actually funding the film. People who are investors and may not have any experience in the film business could also fill this position. Or the EP could be someone in the business who is hired to supervise the production for the investors. Having this title helps them retain fiscal control. In higher budget films the EP could be the representative of a company that has invested in a film, and hired to oversee the production. Or he could be a wealthy investor who has put a significant amount of money into the film (sometimes millions). In some cases, though rare, this position could be what is known as a courtesy credit. This means it is someone who may have invested heavily but takes little part in overseeing the production, relying instead on a good line producer.

There are many different styles to producing. Some EPs prefer to oversee at a distance, merely reading production reports and watching dailies on video or digitally. They would still have the right to approve or not approve significant budget or script changes, anything that would significantly change the original essence of the project. Their authority is still in place, and they have the right to step in at any moment if there is trouble, but they rarely come to the location. In fact, if you have this kind of EP, and she does show up at your location, you can bet there are problems somewhere, perhaps with the budget or dailies. If that same EP is actually seen on set for a while, there is an even greater level of trouble, most likely with the director.

Then there are the more hands-on EPs. These kinds of producers are frequently on location, and may occasionally be on set. They scrutinize the rushes, sending notes to the producer and director daily. Some films may have more than one EP. I once worked on a picture that had three EPs. Two of them were people who had invested their personal money in the film, and one was a representative of a production company that invested money in the film. Having multiple EPs can get complicated, depending on their involvement. It is easier to get approval for something from one person, rather than tracking down three. In addition, the three members must agree on certain issues related to the production, which is no small feat. Just remember that each situation is different. Following is a list of possible duties for the EP during pre-production, production, post-production, and wrap.

Pre-Production

- May have shopped the script around and raised funding for the film.

- Approves the budget based on the amount of money invested in the project.

- Approves or hires the producer and sometimes the director.

- Holds meetings with producer and director to discuss vision of the project.

- If it has not been done already, may secure distribution for the project.

Production

- Reviews production reports to monitor the progress of the shoot.

- Steps in if there appear to be problems, such as using too much overtime, or maybe the director is shooting too much footage. Usually the EP will rely on the producer to deal with most problems.

- Approves more funds if warranted. For instance, I worked on a film once where there was so much rain in the city where we were shooting that we lost a full week over a two-month period. The EP was consulted and deemed it necessary to shoot another full week, which cost the production extra money.

- May review footage to monitor the progress of the project.

Post-Production

- Reviews all cuts of the project to see how it is taking shape and makes recommendations.

- Works with the producer to spend out the budget.

- May review/approve marketing materials for distribution.

- Works with the distribution company to assure delivery of the project.

- Works on his or her next project.

There are certain qualities that make for a good EP. An EP:

- Is a self-starter. This is not someone who is sitting around waiting to be hired.

- Is entrepreneurial enough to create his or her own job.

- Is a good leader, able to be perceptive with deals and people.

- Understands the industry, has a vision for it, and yet has business expertise.

One other note about EPs. I recently executive produced a film where I represented the investors. I made sure in the development phase that the operational agreement (contract between the investors and the production company that produced the film) gave me the right to approve the budget, the hiring of the director, any script changes, and that we had input in the post-production process. I could have negotiated for final cut approval, but had confidence in the line producer to take care of that. Just understand that there are no hard rules here. In this industry you get what you negotiate for.

Line Producer

Line Producer

Learn how to get a better understanding of people skills and have a very strong grasp on your storytelling ability. Really understand story, and that means not getting in the way of the story being told. You can’t grandstand just because you want things a certain way. When the director’s doing something, you gotta be there to support them, you gotta know how to support that vision and make sure you hire the right people.

Stephan Schultze, Producer, Executive Director of Cinematic Arts, Liberty University

The producer, also often called the line producer, works directly under the EP. Sometimes in low-budget film productions the producer may even be the same person as the EP, if he has put the package together and secured funds for the project. Just like the EP, there are different styles to producing. Some producers are very hands-off, hardly ever showing up on set. However, some producers like to go to set every day.

If the producer is also the EP, she is responsible for everything. One rule of the industry is that if the film succeeds, the director is praised. If the film fails, the producer is blamed. This is why in some cases the producer may have ultimate creative power. Keep in mind this is especially true for television work. Also keep in mind that in certain situations the producer may have less creative power than the director. The creative power resides in the person with the most influence or experience in the industry.

How much a producer does in terms of responsibilities may depend on the budget. The rule is that you do everything until you can hire someone else to do it. The kind of project you do also can determine the producer’s level of involvement. For instance, if the project is a documentary, the producer often functions also as the director and often the editor. When producing live events, the producer must be hands-on with all the many details to pull off any type of event. If you are producing animation, you can afford to be less hands-on and rely more on your director of animation to pay attention to the details. Following is a list of duties for the producer during pre-production, production, and post-production.

Pre-Production

- Puts together the budget. This process, discussed in Chapter 3, may involve receiving bids from various department heads. For instance, a production designer may submit a budget for the art department. The producer will review this bid and approve or make changes as the overall budget permits.

- May hire the director.

- Hires the UPM.

- May hire an assistant, if the budget allows.

- Works with the director to define the vision of the project.

- Meets with the director and production team to assure pre-production matters are being handled.

- May work with the director and director’s team on the scheduling of the shoot.

- Sometimes makes the distribution deal.

- Goes on location scouts. The producer does have the power to veto a location if he feels it does not fit the overall vision of the project.

- Approves cast.

- Approves script changes (this goes on during the production as well).

Production

- Answers to the EP.

- Helps support the director to get the vision they have discussed. Again, different producers have different styles when doing this. The approach depends on the relationship with the director. There must be a certain level of trust between both parties. Some producers tend to be overbearing. A good producer will find a way to bring the best work out of a certain director, still maintaining control without being domineering.

- Oversees management of the budget with the UPM.

- Attends dailies.

- Discusses footage with director to ensure progress of the project.

- Approves budget expenditures.

- Approves the production report (if shooting film).

- May visit the set to ensure the shoot is progressing well.

Post-Production and Wrap

- Reviews all cuts of the project and makes recommendations.

- Oversees wrapping up the final budget with the unit production manager (UPM).

- May pay for the wrap party. The funds for the wrap party may also be covered under the production budget.

- Pays for crew gifts. Crew gifts can be as simple as a T-shirt or ball cap with the project’s title, or as expensive as a quilted jacket at $100 per person. Some crew gifts are more creative. I once worked on a film that was about a duffle bag of money that fell off a Purolator truck. Each crew member received a duffle bag and money clip decorated with the project’s title. What and how expensive the crew gift is depends on the resources of the producer.

- Approves the final cut of the project.

- Delivers the project to the appropriate personnel.

Working with First-Time Directors

Working with First-Time Directors

As a producer, you may be shooting in low budget and run across a few first-time directors. First-time directors have a few qualities that a producer needs to watch out for. Here are some things to keep in mind:

- First-time directors always try to shoot too much. They have not yet learned the economics of shooting. Also, they are most likely nervous, and figure the more they shoot, the more footage they will have, and the better their chances of making a good film. A good producer needs to weigh this tendency in a new director to allow some freedom while retaining control so as to protect the budget.

- Some first-time directors are more concerned with shots than story or acting. This is very common. Many directors think the cool shot will showcase great creative talent. Seasoned directors have gained perspective on this and understand the importance of good performances and storytelling.

- First-time directors get tunnel vision. Tunnel vision is the ability to see in only one direction, and narrowly. It is not necessarily bad. This trait allows directors to attend to the detail of a scene, a performance, and a moment with great intensity. The problem with tunnel vision arises when a director cannot see outside his or her own world, and this sometimes translates into budgetary nightmares. Directors are not hired to watch the budget, nor do some of them feel responsible for it, which is another reason why good producers are so important. A good producer is adept at keeping the wider, overall vision of the project, which may be desperately needed to ensure the final vision is achieved.

- Some first-time directors don’t do shot lists. This is usually because they don’t know how. I’ve worked with many a director who did not do shot lists. However, these seasoned professionals had gained enough experience to shoot confidently “off the cuff.” A good producer will encourage, and even sometimes demand, shot lists from a new director.

- Many first-time directors have little endurance. They tend to relax after principal photography because they are not used to the long days and weeks it takes to shoot a project. A good producer will keep on the director through her contracted role in post-production, and keep her on a timely schedule.

Associate Producer

Associate Producer

The position of associate producer is one of the most misunderstood in the industry. This is because the position varies so greatly from project to project. In low budget you most likely will not have this position. In medium to high budget this position could be many things. In television the role is clearly defined, but not in film and digital work. I once worked on a high-budget film where the associate producer was a friend of the producer who typed script changes. I have even seen an associate producer who was the producer’s nephew and needed a film credit. Historically the associate producer is the person who guides the picture through post; however, these days that position is being called the post-production supervisor.

The associate producer may also be someone who consults on the picture, in a certain area of expertise or technical acumen. The role of the associate producer is often a judgment call, a courtesy credit. This should not be surprising. Read the credits on many films and you will constantly see new titles. Producers are thinking up new titles all the time. I once worked on a film where I received credit as a production associate. I was given this title because I had done two different jobs on the picture but could receive only one credit.

Assistant to the Producer

Assistant to the Producer

Becoming a producer can happen pretty quickly if someone is motivated enough. Some people, however, choose to learn the ropes by working for a producer first. In this case, becoming an assistant to the producer is a great job for newcomers to the industry. This position allows the person to sit in on important meetings and, if aspiring to be a producer, learn firsthand how to produce. The assistant gets to know what is going on all the time. This puts the assistant in a very valuable position, as communication is extremely important on a production. The main job, obviously, is to assist the producer. This assisting could involve a variety of duties, depending on the proclivity of the producer. Different producers give different responsibilities to their assistants. The assistant may begin work at the discretion of the producer and continue working through post-production, budget permitting. Following is a general description of the range of duties that may be required of an assistant:

- Answers the telephone for the producer and screens calls. This is a position that requires discretion.

- Could type script pages for the producer. A good knowledge of the different screenwriting programs is essential.

- May schedule meetings with a variety of crew members, the director, and possibly studio executives, if it is a studio shoot.

- Sits in on production meetings, usually to take notes for the producer, execute conference calls, and get coffee.

- Becomes the voice of communication with the studio and/or certain crew. This is merely to save time for the producer.

- May be involved in more personal matters such as picking up the dry cleaning, walking the dog, or scheduling a haircut.

Qualities of a Good Assistant

- Reliable, resourceful, and respectful of the producer’s position.

- Understands production well enough to be discrete at appropriate times.

- Has adequate scheduling and secretarial skills: typing, faxing, and telephone.

- Is willing to learn and work without attitude.

Producing in the Field

Producing in the Field

While the general responsibilities of a producer cover lots of different media, there are some important differences in shooting various kinds of projects. Shooting in the field is a term often used for television applications where an interview is conducted with some sort of expert in an office location, or it can be doing an interview with “MOS” (man on the street). Sometimes producing in the field is for short features or stories that will be used later as part of another show. Shooting in the field is also synonymous with documentary work. The key to successful field producing is planning. Here are some issues that will need to be dealt with:

- Crew: The type of material you need to get will determine the kind of and how much crew you need. In some cases, such as short features, you may only need a cameraperson and possibly one sound person. If you are doing only interviews, it will be just you and the cameraperson. If you are shooting some reenactments, you may need camera, sound, lighting, and grips. Some of this crew can be hired locally, such as sound, lighting, and grips. Check with the film office where you are shooting, as they often have directories of local crew people.

- On the road: In the field more than likely means you will be going somewhere, whether it is locally or across the globe. If your company does not have coordinators arranging your travel, you may need to do it yourself. Make sure that hotel, airfare, and per diem for the crew are secured before you head out. Also make sure your crew are securing the necessary equipment you will need. In addition, in case of equipment failure, have backup equipment, or the location of the nearest equipment rental houses, should you need them. If you are shooting internationally, be aware of that country’s requirements for visas and/or immunizations before entering the country.

- Location issues: As with location shooting for feature films, shooting in the field means shooting on location. This kind of shooting has much of the same policies regarding location agreements and permits. See Chapter 15 for a more detailed explanation of dealing with your locations. That said, because shooting in the field generally takes a small crew, many people try to shoot “on the fly” (meaning they simply pull up, set up the camera, and grab some footage without dealing with location agreements or permits). While this can be successful, it’s not entirely legal. It’s better as the producer to cover all the bases legally so you don’t incur any fines or break the law.

Producing Live Events

Producing Live Events

Once someone has tasted live and they love it, it’s an addiction and you can’t get away from it. That’s why I could never do film; where you stand around for 24 hours waiting for one three-second shot. I couldn’t do that to save my life. I don’t have the patience. Live is producing on steroids, being able to create a checklist and then juggle the checklist and check everything off your checklist. And the more elements and variables that you create, the more fun you have.

Norman Mintle, Veteran Media Producer and Dean

School of Communication & Creative Arts, Liberty University

Producing live events is where many feature film and television producers start out. A live event, of course, differs from producing a media show in that there is usually no post-production. However, the process of going through pre-production is somewhat the same. Then, the actual event is much like doing live television or theater. Everything should be in place enough that the event runs itself. There are two kinds of live events: those that are recorded, either for DVD, Internet, or television, and those that are not filmed. For both, there are many considerations and steps to take, starting with pre-production:

- The final outcome: Live events is such a broad format that you could be producing anything from an awards show to a fundraiser to a retrospective or festival. An important element of all of these is the final outcome. What will your attendees leave the event with? One element that can cement the event in their minds is branding the event. There should be some sort of logo, slogan, or phrase that sums up what the event is about, its purpose. Part of that branding lies in the design you choose. That design is then carried through to items such as the invitations, posters, programs, and advertising. This gives the event an aesthetic continuity and also an identity.

- Publicity and advertising: The scope of the event usually determines how much and what kind of publicity and advertising needs to take place. If the event is public, then you will want to advertise with commercials, local businesses, radio, cable, and public television. You should first draw up a press release that contains all the relevant information about the event, time, place, purpose, and so forth. In addition, creating posters, flyers, and mailings (email and snail mail) that are strategically distributed could make the difference in your turnout. Consider social media and timed announcements at various intervals, increasing them as you get closer to the event. Of course, if the event is not public and invitation only, your advertising is minimal.

- Budget: As with all production, the budget you have will determine many things, such as what kind of venue you can afford and how much crew and/or production design you can afford. If appropriate, consider sponsors for the event. Sometimes businesses will donate funds to an event in exchange for having their advertisement appear in the program or appear in some of the elements of the venue (on a screen, stage, or banner). Sponsors will want to know that the event will give their company exposure to the right audience. Obviously a nonpublic event would only appeal to certain sponsors, who still might want to target a certain audience. Other sponsors might be seeking more of a public exposure, which then works well with public events.

- Venue: When deciding on a venue, there are logistical considerations such as setup, how long will the event take to set up in a particular venue, is there good access for equipment and services, and so forth. In addition, consider cleanup, emergency services, or any security that might be needed. Ultimately, though, the venue has to match the scope and purpose of the event. I once produced an event that was to be a forum with panels and speakers. The venue was more of a screening room for films, so there were challenges in acquiring the right stage equipment for forum panels and speakers. We chose to trade the practicality of a different venue, in place of a beautiful screening room, which again, produced some challenges, but worked out in the end.

- The crew: Your crew could consist of many people, depending on your needs. Certainly you need to hire a photographer to capture the event. Be sure to discuss with your photographer what specific shots or people to capture. You could also hire a videographer. Be sure to understand and communicate what the cameraperson should shoot. To answer that, think about why you would want the footage. Do you want to create a promo piece later to promote an annual event or raise funds? Do you just want a recording of the event for its own sake, or something that may be distributed to those who took part in it? Answer these questions and you will know what to tell your videographer to shoot. Other crew you might need is determined by the venue itself. Whether the event is public or not, when people show up, they need to know where to go. You should have greeters and ushers to guide people to where they need to go. In addition, participants in the event need to come early and perhaps rehearse. Assigning someone to escort and monitor the talent ensures they will be where you need them, when you need them. Finally, if your event involves local or national celebrities, as is often the case, consider hiring security to protect them from unwanted approaches by well-meaning fans.

It’s as though you were putting together a puzzle whose pieces constantly change size and shape. You have to be very adept at reordering and reorganizing.

Norman Mintle, Veteran Media Producer, Dean

School of Communication & Creative Arts, Liberty University

- The cast: Any live event needs a host or hosts. Choosing the right one for your event is crucial. The host should be professional but, more importantly, appropriate for the event. Do not get a comedian for an event that honors victims of some tragedy. Think about what kind of personality is appropriate.

- Production design: Some events are bare bones because of the budget, while some can have high “production value” if affordable. If the venue needs some aesthetic touch-ups, you will need to hire a production design team or decorators to embellish the venue. This could mean anything from flowers and plants to make the room look nicer, to building dozens of displays that take up the entire venue. Make sure the venue owners know and approve exactly what you want to do ahead of time. In addition, it is good to have these changes to the venue outlined in the venue contract to avoid confusion and conflict later.

- Invitations: Invitations, if your event calls for them, are something that should be done early in the process to allow for RSVPs if needed. Generally, you should send out the invites via snail mail or electronic invitation a month before the event. If the event is larger, such as a charity ball, the invitations should go out more like three months in advance. Make sure you are clear on the invite about the RSVP date and how guests are expected to respond (email, RSVP card, etc.).

- Programs: Most live events need some sort of program to let attendees know how the event will go. The program should use the same branding and aesthetic theme of the event. Be sure to allow time for printing (or copying if on a low budget) before the event.

- Admissions: If the event is free, you won’t need tickets; if it is not, you will need tickets printed, for admittance. Make sure your ticket takers tear them in half so that you can keep a count of how many people attended. Low-budget events use regular tickets that can be bought at an office supply store. Bigger-budget events may use elaborate invitations with formal custom tickets that guests bring to the event. Determine what kind you will use as per your budget.

- Logistics: If your event has seating, pay attention to general seating, assigned seating, or reserved seating. Your ushers can escort guests for reserved seating as they enter. Make sure the reserved section is securely cordoned off. You also need to make sure you have proper accommodations for any physically challenged attendees, with adequate access for wheelchairs.

- Parties and food: Your event may have a pre-event party that could involve the host, talent, presenters, and so forth. Make sure you allow enough time for these people to travel from the party to the event, along with enough time for a walk-through or rehearsal. Many times people also have an after-event reception. Typically, the caterer will set up as the event is taking place. Be sure to have someone monitoring the caterer so that he is ready in time. You don’t want people walking into a reception when the caterer is still setting up.

- Legal matters: You will need to do a contract with the venue that outlines the parameters, date, and time of the event. You would be wise to have a lawyer go over the contract to make sure there are no hidden stipulations. Most venues will also require insurance from you. This is in case any damage is done to the venue, and then your insurance would cover the damages. If your event is outside or on public property, you may need permits to hold the event, and for parking vehicles at or for the event. Your local convention and visitor’s bureau should be able to help with this. Other legal paperwork you may need is releases. If the event is being filmed for other media distribution, you may need release forms for your talent and perhaps the audience. For the audience a crowd release placed in a conspicuous area (see the online forms for an example) will suffice.

- Props: If your event has some form of awards tied to it, you will need to acquire the awards or plaques well before the event. Simple plaques may only take a couple of days, but elaborate awards could take quite a few weeks, so allow for plenty of turnaround from the time you order them to when you need them.

- The script: Even free-flowing events need a script. The script could be for a show with general timings for each element of the event, or, if the event is being filmed, could be a very detailed outline of each element as per each camera with audio cues. Either way, the script needs to show each component to insure the event runs smoothly. All personnel, including the host, guests, camera, and audio people, need this script to keep track of how things need to go. The script should be ready in pre-production and gone over with each person in advance of the event.

- Transportation: Some events provide private cars, airfare, and maybe even hotel for talent, hosts, or crew. It’s a good idea to have a production coordinator to take care of these details for you. That person will make sure to know where these people are at all times and get where they need to be.

- Production: Now that everything should be in place, you need one more check to make sure the event runs smoothly.

- The walk-through and rehearsals: It is imperative that you either do rehearsals for an event, if warranted, or hold a walk-through. A walk-through takes all personnel (host, talent, camera, and audio crew) through the event, element by element. This should be done right before the event and can take anywhere from 30 minutes to a couple of hours. Always budget for more time than you think you need.

- Craft services: You should provide some sort of craft services for people working or taking part in the event. This could include just water and some snacks or something more elaborate such as drinks, coffee, and hot hors d’oeuvres.

- Payroll: All events will cost something. Be sure to be prepared to pay personnel, the venue, and services the night of the event. Some venues and caterers may require partial payment in advance and full payment the date of the event. This is normal. Just be prepared to provide checks at the end of the event.

You have to be ready. You have to be resourceful; you have to be contingency minded. You have to be thinking, “Oh, what if.” You always have to have the “what if” backup plan and be ready to go. If you’re not ready, in live events, then you’re left with mud on your face, because the show must go on.

Norman Mintle, Veteran Media Producer, Dean

School of Communication & Creative Arts, Liberty University

Producing Documentary

Producing Documentary

Certainly there are volumes of books that explain the process of documentary production. This section does not intend to go into that amount of detail but rather to discuss documentary from the producer’s perspective. In other words, what is important about producing documentary, as opposed to other content? With documentary it starts with a problem. The way to look at and explore that problem, in a documentary, starts with research.

- Research: Most will agree that research is the most important part of the documentary process. For a producer it is crucial not only to identify your problem but also to make sure that your research reflects accurately the context of the problem. You will find after doing lots of research that your perspective as the producer will begin to shape how you want to present the problem. Are you trying to expose a certain issue that no one knows about? Are you examining a well-known issue, but in a new way that viewers will find not just interesting but also fascinating? In this phase you should have some idea what viewpoint you will be taking. That is not to say that it may not change down the road. One of the beauties of doing documentary is that it is much more an “organic” process than narrative film. As you progress through the process you may find information or events that change the way you were looking at the problem. That’s okay. As the producer it will be your job to make decisions about these new directions, exploring some while disregarding others.

- Pre-production: Once the research is at a good point where you have enough information to proceed (research is never really complete until the final edit); you can proceed with pre-production. This part of the process for the producer consists of hiring a great production manager who can take care of the day-to-day running of the production. In many cases a director is hired, although many a documentary is completed by a producer/director. If that is you, great, but be prepared for the work. Doing so, you will live and breathe the project for many months, which is actually not difficult if you are passionate about the subject. During this time your team should be acquiring equipment, setting up interviews, and coordinating travel and any reenactments that might be needed. What you should be doing is continuing to work on the script.

- The partial script: Obviously in documentary you do not start out with a script in the traditional sense of the word. Some documentaries go out with no script at all, and end up with wonderful footage. However, that is risky and creates much more work during post-production. A partial script is what many experienced documentary filmmakers use to provide some sense of the structure of the piece. Again, the structure might change later, but it’s always better to start out with some sense of direction than none at all. The partial script is also meant to make sure what you are trying to say with the film reaches the audience. Seeing the “film” on paper allows you to see what areas might not be clear and require more research. This will help you in the field to insure you get all the footage you need. Sometimes the partial script also helps you as the producer formulate your viewpoint into a communicative form.

- Production: As you begin getting footage for your film, keep aware of the many ethical issues involved with documentary filmmaking. You are going into people’s lives or situations, and they may or may not like what they could see as an intrusion. As the producer you need to be the diplomat, the person who can make people feel at ease and open to the camera. You often will need to negotiate access to people or places in order to get the story you are looking for. You need to be assertive, yet tactful and respectful.

- Travel: If you are in low-budget land and doing much of the work yourself, you will need to take care of travel for your crew, and possibly your talent. As with bigger-budget productions, if you can afford coordinators to handle these details, it will make your life much easier. Chapter 4 has more detailed information about what’s involved in traveling crew.

- Interviews: Most documentaries have interviews with either experts or people who have experienced the problem of your film. Conducting an interview is an art, and not to be taken lightly. As the producer it will usually be your job to do the interview, or maybe your director’s. Make sure you hire a director who knows how to do an interview well. A good interviewer will have questions beforehand that have been gone over and revised as needed. However, do not feel the need to stick to the questions. As the interview proceeds you may find subjects touching upon something interesting. Take them down that path to see where it leads. If it leads nowhere, then get back to your questions. Certainly you want to ask the questions you need to in order to get the information you want for the film; however, frequently you may find wonderful bits of knowledge, conflicts, or unresolved emotions that come up by just having a conversation. Get what you need, but be open to what may come. Also, consider alternatives to the sit-down interview. Have your subject doing something they love, or walking as you talk. The more visually interesting, the better.

- B-roll: If all you did for a documentary were interviews, you would end up with “talking heads” for the length of your film. Nothing is more boring! You need footage to cut into and out of the interviews. This B-roll may take the form of stock footage, reenactment, or other footage you have shot. Either way, B-roll should be visually interesting, and add commentary or meaning to the interview. If much of the B-roll is outlined in the partial script, you will be sure to get it and have much more to work with in the editing room. Even if your piece does not use interviews, or uses very few interviews, getting good B-roll to add to your production footage is always a good idea.

- The importance of conflict: As your filming progresses, do not lose sight of the importance of conflict in a documentary. If there is no conflict, then you may end up with something that is just informational or educational, which may be desirable, or not. A good documentary retains conflict throughout, sometimes never really resolving it in the end. As the producer, it’s your job to keep an eye on the big picture, to insure that everything you or your director is shooting keeps that conflict going.

- Post-production: The wonderfully creative thing about documentary is that post-production can reveal what is called “the found story.” This may be a story that you never intended to tell, but that came about as a result of the footage and/or interviews. As the producer you need to stay open to this, in case it happens; it may just be a better story to tell than the one you originally started with.

- The paper cut: With all the footage you may acquire, assembling it can be daunting. Many documentarians swear by the paper cut. This document lays out your footage on paper in its final version, from cut to cut, including audio cues or narration. It gives you the chance to organize the content and see how the structure of the overall piece is working. You can rework and rearrange sequences until you are happy with them, before doing so with your footage, which is a lot more time-consuming.

- Screenings: As with many media, screening of your work is important. It is especially important in documentary. As the producer, you have a certain viewpoint to the project, and, if you edit it yourself, it can be easy to lose perspective. Hold screenings for people whose opinion you trust, who will be honest with you about the work. Then, go back and rework it, until it’s the best it can be.

Producing Mobile Content

Producing Mobile Content

Producing mobile content is an ever-growing field as more and more portable devices flood the market. That’s good news for producers who are needed to deliver that content. Providers want content that is specifically made for mobile viewing; usually no more than two to three minutes that helps create or promote brands. This kind of content is impactful because it uses actors and characters who people can identify with quickly. Sometimes mobile content can be produced for creative advertising campaigns. Sometimes mobile content provides a lot of interactivity in the form of games. Still other mobile content can be educational, or informational, as in news and sports features.

To produce mobile content is much the same as typical film production in terms of putting together a crew, shooting it, and editing it. Legal issues in terms of copyright, clearances, and releases also apply. Funding can be a little different in that sometimes producers need to self-fund mobile content and then sell it, like a feature film. However, some mobile content providers are dying for content and have started funding or partial funding of some content. The key is in finding the right mobile operators for the right content and then producing what their audience or subscribers want.

Producing mobile content is more than just filming something with a flip camera. It’s staying on top of mobile trends and having an eye for what specific content is needed. Whereas film content originates from a producer, from some inspiration or story to tell, mobile content is consumer based, attempting to provide the public with entertainment or information needed for a specific audience.

Producing Animation

Producing Animation

There are many good books on producing animation that cover the process and technical details at length. To outline all of that here would be outside the scope of this book. However, there is something specific about producing animation that the producer should be aware of. The process of animation has been around for a long time and has been changing rapidly over the last decade. A good producer will keep up with the latest trends and techniques in producing either 2D or 3D animation, or a combination of both. Animation productions can take the form of educational or narrative projects, gaming, and even scientific applications. Whatever the form, the producer, as with most projects, is the leader. One difference in producing animation is the time factor. Most animations take much longer to complete than typical live action productions. Keeping track of your director and director of animation is crucial.

With animation there is not just one production schedule; there are animator’s schedules as well to deal with to make sure that your backgrounds and characters are being completed in a certain amount of time. As the producer you have to have the endurance to keep the vision going, not only for yourself but also for the crew. You will be asked to view a lot of character models, rigged models, and digital or painted backgrounds, and mostly in the early part of the process, as separate elements. Keeping the original idea for the project in mind is your job, to make sure that all of the separate elements are in line with that vision.

The Psychology of Producing

The Psychology of Producing

One final note about producing. Producing certainly takes a lot of management skills. What many new producers might not realize is how much psychology is also in the mix. Leading any group of people inevitably involves people skills. Leading a group of people through the film process, though, can be highly stressful. It means working with widely varied personalities. It means working with artists who react from the heart, rather than from the head. As a producer you need to not only know how to handle film people, but how to handle them well.

Keeping a healthy film set psychologically starts with who you hire. Finding people who are good at what they do and can work well with others is sometimes a rarity in this business. When you do find these people, they are golden. Keep them; cultivate your relationship with them. Take them from show to show.

Yeah, it’s a completely different type of leadership skill. You really have to lead by example and want your team to do a good job. I think very rarely, in any of the projects I’ve done, I’ve actually had to sit down and talk to people and say, “Look, you need to step it up.” The best thing to do when you are hiring people is to find the right personality. Not even so much the right work ethic, because I think work ethic can be taught. If I find the right personality that takes direction well and is a focused person, I find I never have problems with them. So, just getting the right people on board I think is the most important thing.

James Walz, Sound Designer

Other than hiring the right people, you need to know when it’s time to fire the wrong people. This is never easy. I once worked a show as a coordinator. Neither the UPM nor the producer had the guts to fire a really great guy who just wasn’t pulling his weight, so they made me do it. He was also a friend, so it was doubly hard to do. It taught me something though. It taught me how to step up and do the difficult thing, rather than pass it off. That skill served me well in later years on many productions. On one production I had to fire a guy who was not so much a great guy. He was an actor who was difficult to work with and stayed on the production far too long, causing strife wherever he went. His ability to think himself a major star, when he had barely any fame, was astounding. Firing him wasn’t so hard.

Fire people the first day, you will know who they are. Don’t treat actors like they’re precious; treat them like everybody else. The more precious you make somebody, the more precious they demand. So everyone should just be treated equally and respectfully. I think you have a much better set if you treat the craft service person the same way you treat the lead actor, with the same amount of respect. If I place a different value on one or the other, then it’s my fault if they become a diva. I think that’s one way directors get into a problem; they treat people a little too preciously at times, they coddle actors, and then you have a problem on your hands.

Stephan Schultze, Producer and Executive Director of Cinematic Arts, Liberty University

Part of the psychology you deal with on set doesn’t always lead to firing. Sometimes you really need to work with people because they are that good, and really worth the effort. This is where a producer needs to be brave and have some good confrontational skills. I’m not talking about confronting as in arguing, I mean daring enough to confront a situation head on and resolve it. Sometimes that means listening calmly to someone rant and rave. The key is not to get as emotional as the other person is. The calmer you stay, the more the situation will diffuse. There’s nothing worse than a producer losing his cool and screaming on set. The crew looks to the producer and should have confidence that a level head is leading the way. Nothing diffuses a difficult crew member more than a producer who cares yet stays objective in a tough situation and works to provide a solution.

One skill that is essential to any producer is communication. Producers have to be good communicators. That means consistently relaying information that is necessary, at the right times and to the right people. It also means being clear about what you want or need. It’s really that simple.

As long as you are communicating freely and openly and you’re transparent, it’s their responsibility to behave properly. If they don’t, then you need to confront them about that. Some people are really emotionally driven, and those characters, right off the bat, identify them. That person needs very direct communication and no coddling. The moment that you coddle you run into passive-aggressive behavior. So you should take some psychology classes and be able to identify the patterns of behavior you want changed and how they need to be addressed.

Stephan Schultze, Producer and Executive Director of Cinematic Arts, Liberty University

A good producer will also have great leadership skills. There are all sorts of leadership strategies and theories out there, and it wouldn’t hurt aspiring producers to read up on them. Leading people takes great skill and, with the right tools, can be effective.

I always say that producing is 90% babysitting and 10% creative. By babysitting I mean problem solving and sometimes babysitting with your talent, learning how to deal with personalities. You need to understand human interaction. I would say that you need to brush up your EQ (your emotional intelligence), which is all about empathy and awareness of emotion and awareness of feelings, not only in yourself, which is really important, but reading the other person too. The successful producer doesn’t have to be an extrovert, and they don’t have to be a people person necessarily. There are a lot of crotchety producers out there who are very successful. They do need to know how to read the cues and the environment. There are a lot of cues in the environment that many people are massively unaware of and they miss opportunities. You have to be wired for it. It’s a unique calling, it’s a unique wiring. You have to enjoy multiple stimuli coming at you all at once and quick decision making. I think another thing is you have to be very honest with who you are and the intent of your story or your message or your product or your production. You have to remain true to what it is.

Norman Mintle, Veteran Media Producer and Dean,

School of Communication & Creative Arts, Liberty University

A film set is a unique workplace. There are dozens, sometimes hundreds of people working very closely together for twelve or more hours a day, often six days a week for months. Close relationships can and do develop. These relationships will go through stages and inevitably end up with closeness and conflict. In addition, these relationships have to live in a workplace that is highly stressful and constantly changing.

A set is an organism. A set has a life to it. There’s a vitality to a set. And sometimes it ages. It starts off very young and enthusiastic and gets into old age and gets really tired. And sometimes it becomes toxic, like people get sick. Sometimes the set gets sick. The DP is in a really good position to get a feel for what’s the general health of the set. Is it alive and vital and everyone’s invested and everyone’s going forward and everybody’s a part of it? Or are people starting to pull back and pull out because they’ve been trampled or they’ve been abused? They’ve gone 18 hours and they’re on a flat rate and they were promised one thing and something else is happening. They’ve been eating cold pizza for the last three days. There’s a lot of reasons why things will get toxic. The solution sometimes in Hollywood is throw more money at it, but that’s not always the best solution. If you’re a crafts person, then you’re developing your craft, and who are you working with that can help you develop as a craftsman. You don’t have time to work with negative people. No matter who they are. So, you work with people who are positive, who you can grow with.

Doug Miller, Cinematographer

A film set usually takes about two to three days for the crew to “gel.” By that I mean really gain momentum in working together. Once that happens, the pace of shooting can move pretty quickly. This “honeymoon” usually lasts for a couple of weeks, and then about the fourth week or so the crew can start to get tired. This is where the psychology of producing can kick in. Deal with the problems, confront personalities, lead and motivate your crew. Tell them they’re appreciated yet stay firm in your standards, and you just may have a successful production.

Film Development

Film Development

The producer or EP is generally the person who works a project from beginning to end. That beginning is what we call the film development phase. The development process covers four major steps:

- Finding the right script

- Working to develop a package

- The contract and negotiation phase

- Striking the final deal and “green-lighting” the project

In the independent film world, the producer may have to obtain initial financing, which is a difficult task when no distribution deals are guaranteed. While they pursue different fund-raising options, producers also have to develop the film along other lines.

Acquiring the Script

Acquiring the Script

The first step in producing any project begins with the script. Even in documentary a partial script is often used to flesh out the story or provide some structure. Whatever the format, the producer may need either to option or buy the script, if it is not an original work written by the producer. Sometimes the producer hires a writer to write something for a show. In this case the writing becomes a work for hire, meaning that the producer, by hiring and paying the writer, now owns the script. Depending on the format, residual payments to the writer may be in order (union work mostly).

If a producer wants to acquire an already written script but has not yet raised the funds for a project, then she may buy an option on the script. This means that the producer essentially keeps the “option” of producing the project for a certain period of time. The writer cannot let anyone else try to produce the script while it is optioned. If at the end of the option period the producer has secured funding, great, the project gets made. If at the end of the option the producer has not raised the money to produce the project, the rights to the script may go back to the writer, who will then have the choice of optioning the script to someone else. At this point the producer could renew the option, or walk away.

If the producer already has funding, she may buy an already written script outright. In this case the writer may give up all of his rights to the script and the producer can do whatever she wants to it. There are no rules here in terms of how the deal can be made. Each situation and deal is different depending on how much money is involved, what kind of project it is, whether the writer is union or nonunion, and how good the script is. Often a producer will acquire a script but not be entirely happy with it. The script may need rewrites, which can be done by the writer (if hired and paid to do so) or the producer. Even later in the process the director sometimes also rewrites scenes or dialogue once the project is underway. As a producer you need to remember that you are acquiring a product, which means you need to have the right contracts in place whether you are commissioning a script or buying an already written script. You may need an option and purchase agreement, a writer agreement, or maybe a collaboration agreement if you are co-writing with someone. Each of these contracts outlines the parameters of the agreements such as how long the contract is for, what work it is for, how credits will be given later, what the compensation is, whether the contract is renewable, and more. Make sure a lawyer is involved in this part of the process to insure you get everything you want and need. See the online forms for some examples of these contracts.

Working with Writers

Working with Writers

If you hire a writer to write or rewrite a script for you, it is important to know how to communicate with a writer, in order to get the best work out of him or her and to ultimately get what you need, a great script. Writers are artists who will sometimes spend hours pondering a line of dialogue or story point. They often work alone (except in some cases such as comedy writing teams or co-writers) and are comfortable living inside their stories. What many writers have in common is the passion for their work. That passion can translate to someone who is easy to work with or someone who requires a lot more patience. I’ve worked with writers who are very easygoing and will keep rewriting until they give you what you want. I’ve also worked with writers who can’t imagine why you would want to change a single word of their script, and fight you to do so. The key here is personality management. Writers can be insecure and sometimes need lots of encouragement and positive feedback. Some writers do better if you give them very specific notes on the script, while others do better if you only give them a general direction to go in. Know your writer and not only how he likes to work but also how he works in a way that will give you the best script possible.

Developing the Package

Developing the Package

If a producer has found the right script, he develops a number of items that will help shop the script to potential investors. These include:

- The logline

- The treatment

- The step outline

The Logline

The logline has various uses and can help describe your project in a concise manner. The logline is a very brief one-or two-sentence description of the story. It could look something like this:

On his deathbed, a father tells the story of his life the way he remembers it: full of wild, impossible exaggerations. His grown son tries to separate the truth from the fantasy before it’s too late. (From Big Fish, 2003.)

As you can see, a logline must have the following:

- The protagonist

- The protagonist’s goal

- The antagonist/antagonistic force

Make sure you clearly state the protagonist’s main goal. This goal drives your story, and it will help you write the logline. Also be sure to describe the antagonist in the story.

A well-written logline will describe the action of the story, as well as the energy that drives the story forward. Just check out any film poster, and you will see many examples of loglines.

The Treatment

There are a couple different kinds of treatments out there. Sometimes a treatment is only one page long; sometimes it can be twenty or more pages long. The treatment you use when you’re trying to sell a script is the one-page type, with a few specific items to keep in mind. A treatment in the development phase is a one-page document that tells your story.

It is meant to excite the reader into wanting to see a film made. This, like the logline, goes with the adage, “Don’t tell your story, sell your story.” A treatment is meant to make the reader want to see the movie, to know more detail about the story. The treatment should have the following elements:

- A working title

- The writer’s name and contact information

- WGA registration number

- A short logline

- Introduction to key characters

- Who, what, when, why, and where

- Act 1 in one to three paragraphs

- Set the scene, dramatize the main conflicts

- Act 2 in two to six paragraphs

- Should dramatize how the conflicts introduced in Act 1 lead to a crisis

- Act 3 in one to three paragraphs

- Dramatize the final conflict and resolution

One final note: while the treatment is meant to entice, it is also meant to give the whole story. That means you must reveal how the movie ends. If you’ve done your job right here, the reader (or potential investor) will be intrigued enough to want to read more. You give them a more detailed accounting of your story in the step outline.

The Step Outline

The step outline is a longer version of the synopsis that lays out the story in more detail. I’ve often seen these written with slug lines, like you see in an actual screenplay, followed by a paragraph or two describing the action of the scene. The purpose of the step outline is to flush out the story. Tell the reader what really happens in the story, as if she was seeing it on the big screen. Someone reading the step outline should walk away with the feeling of having experienced a great story, beginning to end.

Acquisitions, Contract, and Deals

Acquisitions, Contract, and Deals

Now that you have a brilliant idea, it’s time to get it sold! This is a very tricky part of the process. It involves personalities, reputations, sometimes even power plays for no good reason, other than accruing power. It is imperative that as a producer you become familiar with how this part of the process works so you don’t have legal trouble.

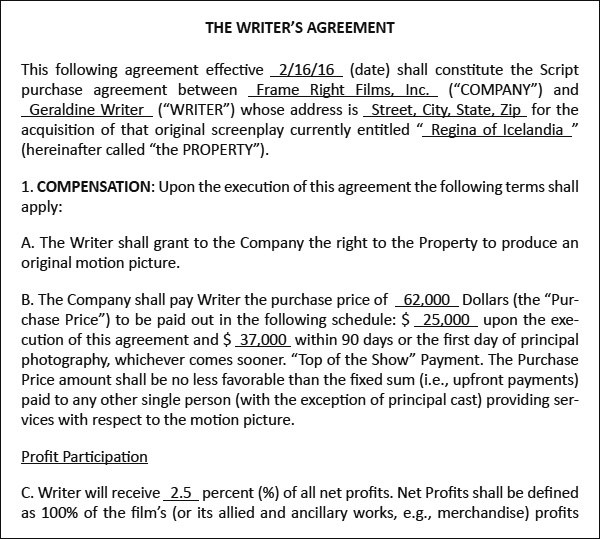

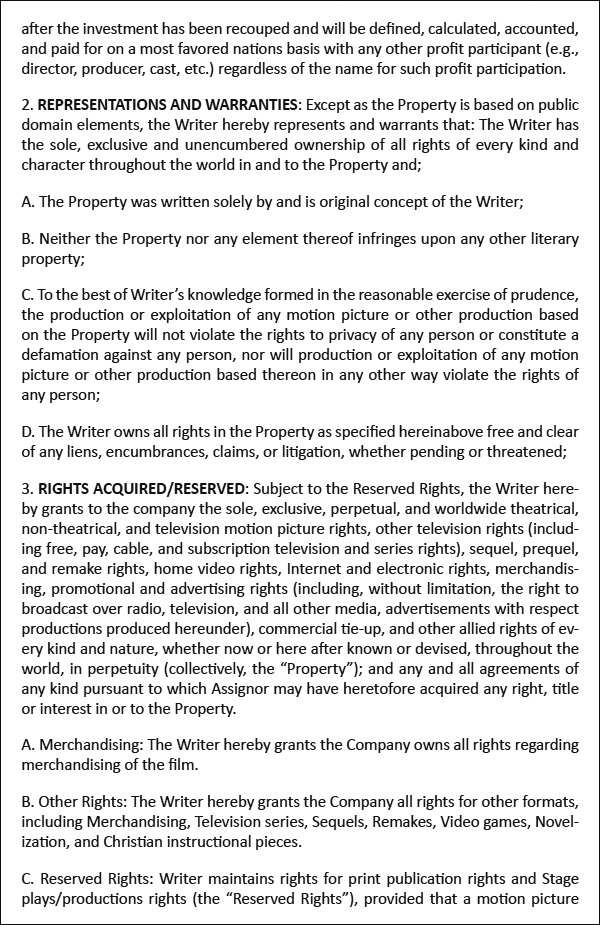

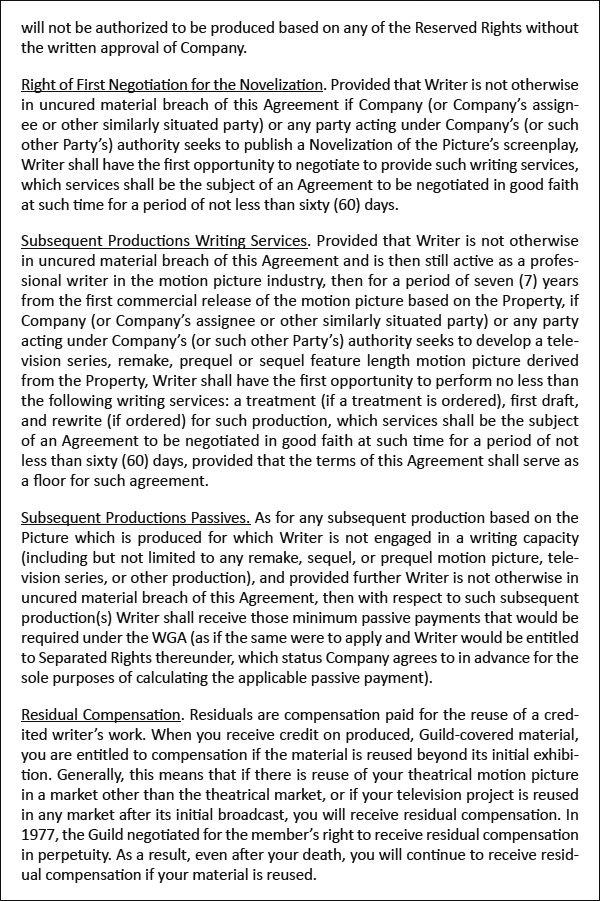

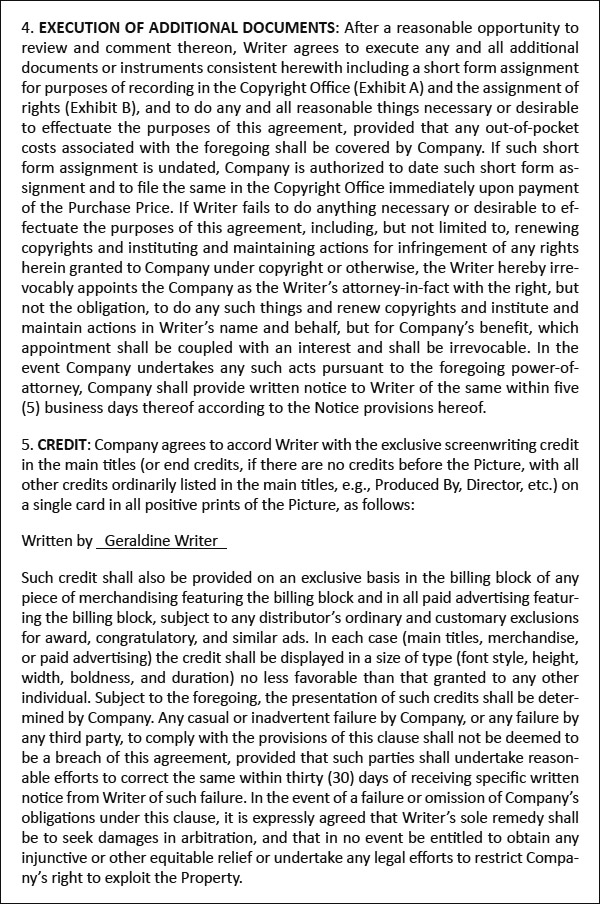

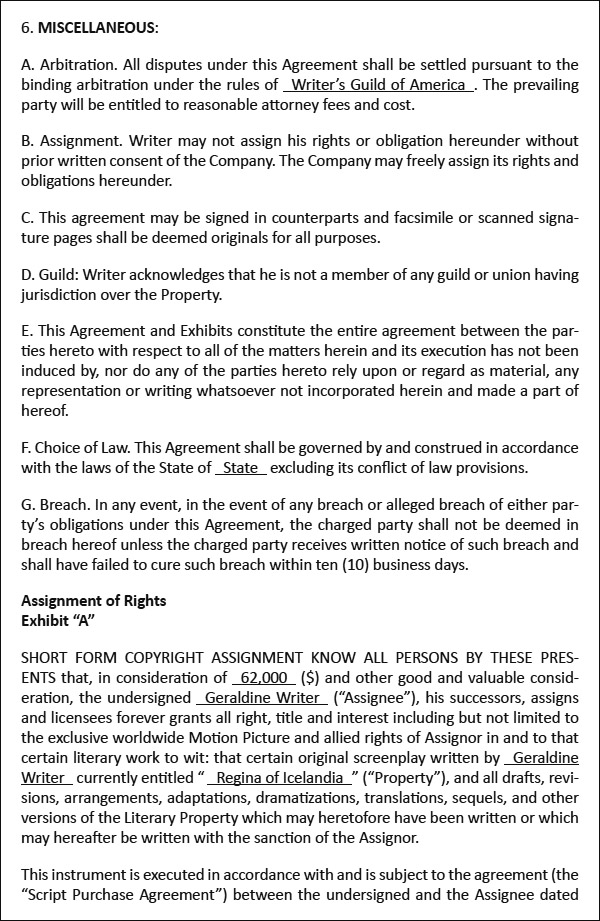

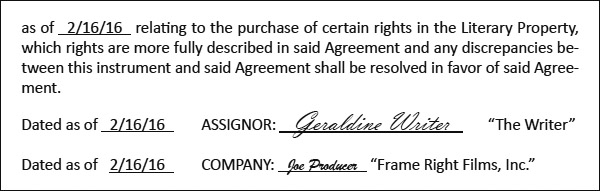

One of the first contracts to be done is the script agreement with the writer (see Figure 1.1). This is an involved contract that covers the terms of payment for the writer as well as any ancillary items such as writing a treatment, a rewrite, or a polish. In addition, it outlines ownership and any residuals that might be due the writer. As a producer, you are not expected to be a lawyer, but you are expected to understand what is in the agreement.

Once the script is contracted, the next step may be to form a company to produce the project. An operating agreement is used in many cases where one company joins with another or one company receives financing from another company to make the film. Often entities will form a separate entity, like a limited liability company, for the purpose of making the one project (or it could be a series of projects). The operating agreement covers many items that will lay out how the company will be formed and operate.

Another part of the package is your ATL, or above-the-line, people. Here’s a little history: Back in the 1980s an agent, Michael Ovitz, became a superstar when he started packaging films for people. He had a knack for aligning the right stars together that would result in a big box office hit. Thus not only did the power of the agent in Hollywood increase, but so did the notion of packaging stars together early on in the process in order to get a project funded. So today this is now common practice. In the development phase, ATL possibilities are discussed and even contacted for interest. So who are they?

- Cast—not the whole cast, just the leads in a project

- Director

- Producer

- Sometimes, director of photography, production designer

Cast: Now think of your project. Based on what kind of project you are doing, who do you think you could get? Who would you want to get? Put together a list—yes, this is the infamous “A” list you’ve heard about from Hollywood. When people talk about A-list actors, there really are actual lists that people draw up, based on actors that are “hot” at that time. Producers and directors study this to see who might be the best in whatever roles they have. And yes, there’s also a B list. These lists are made from actors who are more than likely good box office but less expensive and probably more available.

Director: It’s true what they say, you’re only as good as your last project. The primary thought in the development phase when looking for directors is this: Are they appropriate for the script? Do they have the needed skills for this kind of project? Can they deliver a good story? Can they get great performances from actors? Do they have a history of box office success? Are they good enough now to make a film that can make money?

The director of photography (DP) and production designer (PD): Sometimes when packaging a film, a particular DP or PD might be attached to a project to help sell the ultimate look of the film or to ensure consistency in a franchise. This will require thought on your part, because it needs to be realistic. Don’t just put down some A-list star that you don’t have access to. Your package will appear grandiose. Every wannabe filmmaker thinks their project is perfect for some big star that they’ll never get access to. These people are not taken seriously in the industry.

Once you put all of the pieces together, you have a package that’s ready to be shopped around. Make sure each element is spotless, free of errors and mistakes. This package represents your approach to being a professional.

Summary

Summary

Remember, the producer’s job is to be a leader, to guide a crew through a production to its completion. In today’s market the producer should be well versed in the latest trends and technologies as they relate to producing in the field, live events, documentary, mobile content, or animation. The producer works in development to acquire the right script and develop the package. Producing is part business and part psychology. A good producer will master leading, inspiring, and motivating people to do the best job they can do. If that can be accomplished, you will achieve much more success with your productions.

References

References

“Big Fish,” Internet Movie Database, accessed May 23, 2016, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0319061/.

Dan Bronzite, “Story Planning and How to Step Outline a Screenplay,” Movie Outline, accessed May 24, 2016, http://www.movieoutline.com/articles/story-planning-and-how-to-step-outline-a-screenplay.html.

Marilyn Horowitz, “How to Write a Treatment,” Movie Outline, accessed May 23, 2016, http://www.movieoutline.com/articles/how-to-write-a-treatment.html.