20

Legal Issues

This chapter outlines the important legal and financial issues that come with producing a show. The following sections cover areas such as copyright, fair use, clearances, releases, and contracts. I also explain issues with items that affect every filmmaker, such as insurance and the completion bond. The purpose of the insurance discussion is to simplify the subject for many readers who might find it intimidating. Finally, the legal section explains how having a lawyer, though it may be expensive, may save money in the end.

Copyright and Intellectual Property

Copyright and Intellectual Property

The Free Legal Dictionary defines intellectual property (IP) as “intangible rights protecting the products of human intelligence and creation, such as copyrightable works, patented inventions.” You can think of IP as being the basis for copyright law. The purpose of this being a law is actually to encourage the development of the arts because it grants actual property rights to artists. IP law can also help protect artists from someone else misusing what they’ve created.

Copyright is a huge issue—so large that entire classes in law schools are devoted to it. As a filmmaker, you need to have a basic knowledge of what copyright is and how it works. Copyright is defined by the government as being “to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors … the exclusive right to their … writings.” Most people may not realize, but copyright in a work is established the moment it is in a fixed form, such as when it is written down or saved in a computer’s memory. You actually no longer have to put a © on something, but many still do. Even though your work is copyrighted when you create it, proving that you own the copyright is another matter.

I see many filmmakers worried about someone stealing their ideas. Understand: copyright law protects the expression of an idea, not the idea itself. Copyright protects “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device” (17 U.S.C. § 102). The term original in the copyright law means that the work originated with the author.

How Long Does Copyright Last?

When it comes to copyright, be sure to cover your bases. If you are not sure if a work is under copyright, DO NOT use it. Research it first, and then pay to license it. Copyright lasts for a certain period of time, depending on when it was created. When copyright expires, it falls into the public domain. If a work is in the public domain, it can be used. If not, you need to license the work. If published before 1923, it’s in the public domain. If it’s NOT in the public domain, you cannot:

- Reproduce the music or lyrics

- Distribute it (includes nonprofit)

- Perform it in public

- Play it in public

- Make a derivative work

Check out www.pdinfo.com, an awesome website for everything public domain. Copyright length depends on a few conditions.

Unpublished Works

- For authors who died before 1946, life of the author plus seventy years

- For anonymous works and works made for hire, 120 years from creation date for works created before 1896

- For authors whose date of death is not known, 120 years from creation date for works created before 1896

Published Works

- Before 1923, it’s in the public domain.

- Before 1977, it’s in the public domain if published without a copyright notice.

- From 1978 to March 1, 1989, it’s in the public domain if published without notice and no further registration of the copyright in five years.

- From 1978 to March 1, 1989, it’s in the public domain if published without notice, but was registered within five years.

- From 1923 through 1963, if published with notice but the copyright was not renewed, it’s in the public domain.

- From 1923 through 1963, if published with notice and the copyright was renewed, the copyright term is ninety-five years after the publication date.

- From 1964 through 1977, if published with notice, copyright term is ninety-five years after publication date.

- From 1978 to March 1, 1989, if created after 1977 and published with notice, the term is seventy years after the death of author. If a work of corporate authorship, 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first.

- From 1978 to March 1, 1989, if created before 1978 and first published with notice in the specified period, the copyright term is the greater of the term (95 or 120 years) or 2047.

- From March 1, 1989, through 2002, if created after 1977 the term is seventy years after the death of author. If a work of corporate authorship, 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first.

- From March 1, 1989, through 2002, if created before 1978 and first published in this period, the term is 120 years or December 31, 2047.

- After 2002, the term is seventy years after the death of author. If a work of corporate authorship, 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first.

- Works prepared by an employee of the government as part of his duties are in the public domain.

As you can see, this can get pretty complicated; there are even more specific terms of copyright for sound recordings, which have factors such as whether it was a work for hire, when it was registered, if it was renewed, and so forth.

Copyright Infringement

To infringe on someone’s copyright is to basically steal their intellectual property. If someone infringes on your copyright, or you think they for instance copied something of yours, you must show that your work was original, and that the infringer actually copied the work, or had access to the original. In addition, if the two works are substantially similar, you probably have a case. If someone is found to be infringing on your copyright, the court may prohibit further use of the work, order destruction of the work, or require the infringer to pay damages.

There is one case where the author may not retain full copyright of a work. This happens when you hire someone to, for example, write a screenplay and you pay them. This is known as a work for hire. Here, the employer is considered the author, because the employer has paid for the work to be done. Another case is when two or more people contribute to a work that is considered to be a joint work. In this case the two (or more) people share copyright.

Fair Use

Fair Use

Fair use is a law that allows people to use portions of copyrighted material without the need to get permission or a license. According to the U.S. Copyright Office, fair use is based on the premise that what you are doing is for “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research.” Keep in mind this means limited use without the copyright owner’s permission. When looking at cases that involve fair use claims, there are four criteria a court will look at. These are:

Purpose and Character of Use

Is the work really similar to the original? If it is, that’s not good. Fair use wants the work to be transformative, meaning substantially different than the original. The work must be different enough from the original such that it has a new expression, meaning, or message. Otherwise you’re just copying. This first criterion is considered by the Supreme Court to be the primary indicator of fair use. The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.

Nature of the Original Work

If the original work is nonfiction type material, that’s good. If the original is fiction or an originally created narrative piece, you will have a harder time proving fair use. You have a stronger case of fair use if you copy the material from a published work than an unpublished work. The scope of fair use is narrower for unpublished works because an author has the right to control the first public appearance. Because facts or information benefits the public, you have more leeway to copy from factual works such as biographies.

Amount of Work Used

There are no hard rules here. You should only use as much as you need. Beyond that, the court could be deciding if you used too much and therefore violated fair use. The less you take, the more likely that your copying will be fair use. Your copying will not be a fair use if the portion taken is the “heart.” You are more likely to run into problems if you take the most memorable aspect of a work. A parodist is permitted to borrow quite a bit, even the heart of the original work. The courts have stated, “The heart is also what most readily conjures up the [original] for parody, and it is the heart at which parody takes aim.”

Extent of Harm

Extent of harm is a determination based on how much your work harms the revenue of the original. If use of the copyrighted work deprives the copyright owner of income or undermines a new or potential market, then it is not fair use. Depriving a copyright owner of income will trigger a lawsuit. It’s possible that a parody may diminish or even destroy the market value of the original work. That is, the parody may be so good that the public can never take the original work seriously again.

A Note on Lawsuits

A Note on Lawsuits

It is important to note that just because you think your work is protected under the fair use doctrine does not mean that the owner of the copyrighted content cannot sue you. They may still report you as violating copyright law. If you are someone using a copyrighted work and wonder if you are under fair use, the best idea is to get a lawyer. However, here are some other things to keep in mind. Give some credit. You are actually not required by law to give credit when using someone’s work. However, it’s a good idea.

If you happen to catch something in the background of your frame, whether it is music or a poster, it could be considered fair use. Keep in mind if a lawsuit were to occur, the court would still look at the amount of use and how “incidental” it is.

Parodies

Parodies

One of the biggest uses of fair use is in parodies. In the United States we have the right to review, comment, or make fun of pretty much anything. If your work is a parody, a clear parody, then copyrighted works in there would fall under fair use. You still need to be careful. There have been cases where someone claimed fair use, but the court decided the work was not a parody and therefore infringed on the person’s copyright.

U.S. copyright law does cite some examples of activities courts have decided were fair use. These include:

- Quotation of parts of a review or criticism for purposes of illustration or comment.

- Quotation of short passages in a scholarly or technical work, for illustration or clarification.

- Use in a parody of some of the content of the work parodied.

- Summary of an address or article, with brief quotations, in a news report.

- Reproduction by a library of part of a work to replace a damaged copy.

- Reproduction by a teacher or student of a small part of a work to illustrate a lesson.

- Reproduction of a work in legislative or judicial proceedings.

- Reproduction, in a newsreel or broadcast, of a work located in the scene of an event being reported.

Fair use has a lot of gray area. It is not always clear or easily defined. There is no specific number of words, lines, or notes that may safely be taken without permission. Acknowledging the source of the copyrighted material does not substitute for obtaining permission. When in doubt, consult a lawyer who specializes in fair use.

Clearances

Clearances

A clearance is legal permission to use an item that appears in your project. If you are using copyrighted music, you will need permission to use, or license, that music. If you plan to show some brand-name soda in a scene, you may need clearance from the soda company. Any product that has a brand name, including wardrobe labels, food, beverages, cigarettes, and cigars, may require clearance if it is clearly visible and identifiable in the frame. In most cases, as long as the product is being used for its intended use, you may not need to contact the company. However, even if the product is being used for its intended use, the company may not appreciate being in the type of film you are making and may have concerns about the image of the company being shown in your film. If you are not sure, check with your lawyer.

Items that may require clearance include the following:

- Stock footage.

- News footage.

- Film clips.

- Television clips.

- Excerpts from published written works.

- Portrayal of well-known celebrities or politicians.

- Names of characters, businesses, products, artwork, and state and government officers.

- Derogatory references in dialogue. A derogatory reference could be a character referring to an actual, known person as racist or a pedophile, something that would be injurious to this person’s reputation.

- Inaccurate factual statements. These statements not only may be inaccurate but also could qualify as defamation. For instance, a character could say that a known company knowingly manufactures products that are addictive, deceiving the public. If that statement is untrue, the production company could be sued for slander.

- Statements that might constitute invasion of privacy, libel, or trademark or copyright infringement.

- Telephone numbers. Most productions use the typical “555” prefix, with the rest of the number being above 4000, which is not used by any telephone company.

Clearances are sometimes handled by a studio representative who works to find possible clearance problems in a script, bring them to the attention of the director and producer, and either obtain clearance or suggest their removal from the script. If there is no studio representative, a script clearance company could compile clearance reports. These reports point out possible problems. Some of these companies will also work to obtain any permissions needed.

Releases

Releases

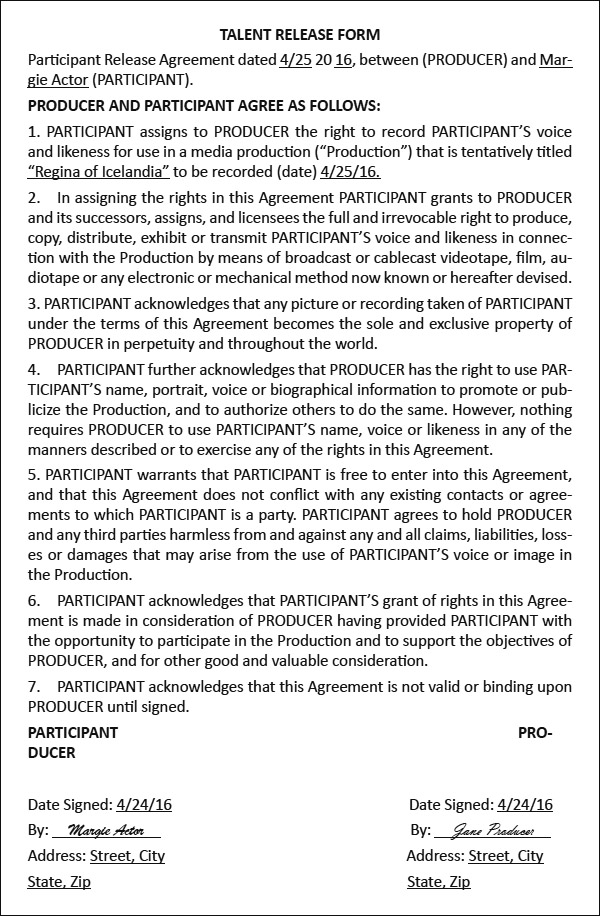

Releases are agreements between you and another party, in which the party agrees to let you photograph or record her (see Figure 20.1 for an example). Releases are typically necessary for actors, animals, or stunt people, those that are seen on the screen. If photographs of a person are used, releases may also be necessary for the people in the photograph.

Releases are also needed for locations (see Chapter 15 for an example). In higher-budget shoots, a production will post a notice if shooting will occur in an area where a crowd will be used. The notice states that, by being in the area, the people are granting the production the right to photograph them. Thus, no individual releases are needed. If, however, a large number of extras are employed to work as background, then an individual release is obtained for each person.

In low budget, where hiring extras is a luxury not many can afford, some projects will use their crew and anyone they can grab for background. Many low-budget deal memos contain a release in them so that the crew member can be placed at any time in front of the camera. If the production is snatching people for the background on the spot, releases must be obtained, but only for those people who are recognizable. A person walking far in the background, where you cannot make out his face, would not need a release.

Contracts for Cast, Crew, and Services

Contracts for Cast, Crew, and Services

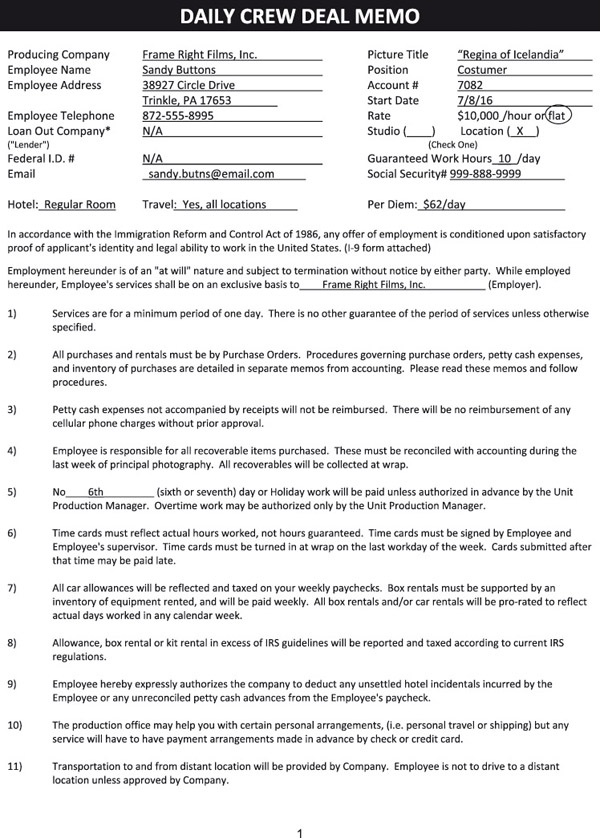

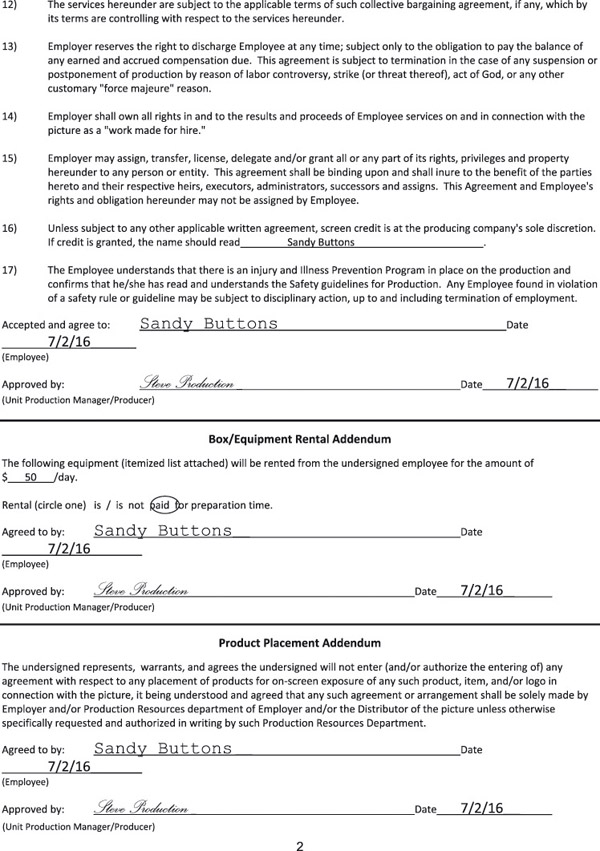

The basic contract for a crew member is called a deal memo (see Figure 20.2). This deal memo is an agreement that states you hire the crew member for a specified amount of time and for a certain rate. This chapter will examine some of the clauses in this kind of contract.

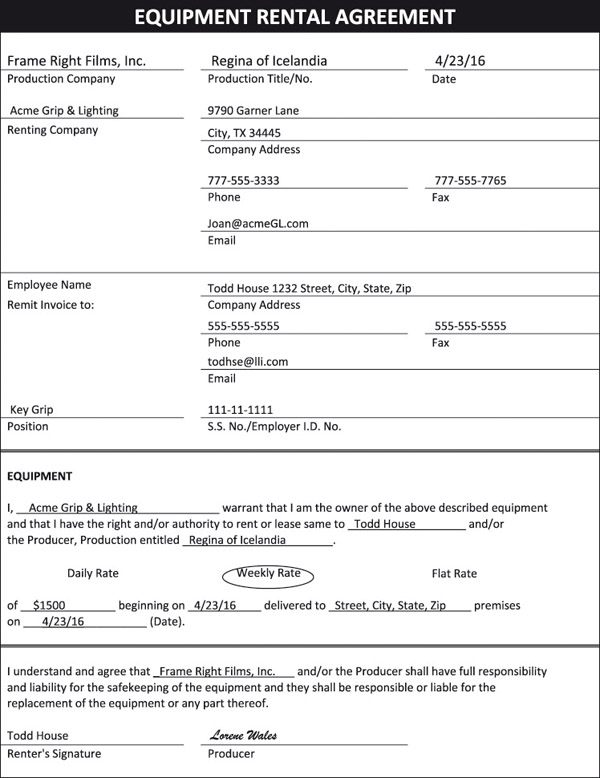

Other contracts include agreements for equipment and services. An equipment agreement (see Figure 20.3) states the items to be rented, how long they are to be rented, and at what cost. This kind of agreement may be contracted with a company or an individual who may own certain equipment.

Insurance

Insurance

There are a couple different kinds of insurance that are necessary on a project. These include errors and omissions and a traditional production package. You purchase this insurance from insurance companies that specialize in entertainment insurance. When you apply for insurance, the insurer will want to know what your experience is, if you have had insurance before, and if there were any previous losses. The insurer will also want you to outline any stunts or use of animals, vehicles, explosives, or fire.

Errors and Omissions

Errors and omissions is a type of insurance that covers the production if anyone tries to sue you. The intention of errors and omissions is to cover only cases in which you inadvertently infringed on someone’s copyright or committed slander, invasion of privacy, plagiarism, unfair competition, or defamation (see “Glossary” for full definitions of these terms). If there is willful infringement, the insurance may not cover legal costs. For instance, if someone claims that you stole a story idea, he could sue you. This type of insurance helps pay legal costs to resolve the matter.

Production Package

Production package insurance is a type of policy that is specifically written for projects in the entertainment industry. This package typically contains four different kinds of insurance: cast, negative, third party, and faulty stock. Each policy for a production will differ depending on who or what is being insured. For instance, shooting at a person’s house that may have expensive furniture or artwork might require higher liability coverage on the policy.

Cast

Cast insurance covers costs incurred if for some reason a cast member is injured or killed on set or in post-production. These costs could go for reshooting or using CGI to cover the scenes that the actor had yet to shoot. The decision to reshoot or use CGI is usually based on how much of the actor’s scenes have been completed. If only one or two scenes were left, the producer may decide to rewrite the scenes, omit them, or use CGI.

Negative Insurance

This insurance covers your film negative (if there is one). If your negative is somehow lost or destroyed, insurance would cover the cost of replacing this negative. This translates into the amount it would cost to reshoot those scenes. Negative coverage also includes items related to your negative, such as audio disks, drives, or DVDs. Recently, negative insurance has also been expanded to include the loss or damage of most formats.

Third-Party Insurance

Third-party insurance covers items that are rented or borrowed from a third party. For instance, if you were to rent an expensive fur coat for a scene, and someone spills a bucket of paint on it, then this insurance covers the cost of replacing the coat.

Faulty Stock

Faulty stock insurance covers the cost of replacing and reshooting scenes from any film that may become lost or damaged. Damage to film stock includes that which occurs if the film is fogged or ruined by a camera and any damage that may occur at a lab.

Equipment

Equipment insurance covers any rented or owned equipment such as the camera, grip, sound, electric equipment, and so forth.

Auto

Production insurance for vehicles will cover non-owned or rented vehicles. These vehicles could be picture cars or production vehicles.

Money and Securities

This insurance protection covers any losses to a production’s money and securities during the course of the production.

Extra Expense

The miscellaneous category in insurance would cover a few items common to all productions as well as items specific to your production. Common items include any loss or damage to props, sets, wardrobe, instruments, or owned or rented equipment. Items specific to your production may be added in this column. For instance, let’s say your script calls for a scene where a herd of horses is used. You might add to your policy animal mortality insurance, which would cover the loss or injury of the horses.

Workers’ Compensation

Workers’ Compensation

Workers’ compensation is a form of insurance you pay to cover any cast or crew who may become injured or ill during your shoot. This insurance pays for medical, disability, death, and lost wage benefits. Workers’ compensation will also cover benefits for dependents if a person is killed while working. Some states require that you purchase workers’ compensation insurance from their state insurance program. Currently these states include Nevada, North Dakota, Ohio, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Others do not, but all states require some type of workers’ compensation. This applies to all employees, even independent contractors, unless they provide proof that they carry their own workers’ compensation.

Completion Bond

Completion Bond

A completion bond, also known as a completion guarantee, is a kind of insurance guaranteeing investors that, should a production go over budget or fall to pieces, either they will get their money back or the film will be completed. Most investors or banks would not even consider giving money to a venture without a completion bond. When you procure a bond, you are also agreeing that the bond company can monitor the production. This means the company will receive copies of the call sheets, production reports, and weekly cost reports from your accounting department. A representative from the completion bond company will review them closely, looking for any indications that the film is in trouble. One indication may be that too much film is being shot or that the crew is shooting too many hours. If your project looks like it may go over budget, you can seek additional financing from your investors. However, the bond company must consent to this extra funding.

The process for getting a completion bond is as follows:

- You send a script, shooting schedule, and budget to the bond company. It is important that your budget have a 10 percent contingency. Most bond companies will not insure a project without this.

- The bond company meets with the producer and/or director. At this meeting, the bond company will want to see acquisition documents. These documents include the rights to the story (if applicable) and the script. The bond company may also request that additional personnel attend this meeting, such as the art director or production accountant.

- If the bond company deems the project feasible, it sends a letter of intent to guarantee the film, subject to availability of financing and personnel. This letter of intent can then be used to secure financing.

- Once financing is secured, the producer and bond company sign a completion bond agreement, provided by the bond company. The company will also sign a completion guaranty with the financer. At this point, the completion bond company is paid a fee, which is usually a percentage of the budget minus the contingency.

It is important to understand what a completion bond will cover and what it won’t cover. A completion bond generally will not cover or insure the following:

- The cost of the MPAA seal

- The quality of picture

- Any defects in copyright

- Over budget costs due to currency fluctuations

- Costs not covered in the budget

- Distribution expenses

- Additional shots for a television version

- Anything after delivery of the film

The delivery of the final film is based on specifications set out in the completion bond agreement. These specifications include, but are not limited to, the following:

- The film must be produced in accordance with the budget and production schedule. This does not include minor changes to the production schedule. Rather, this refers to major changes in the time frame of shooting the picture.

- The film is based on the screenplay.

- The film qualifies for an MPAA rating.

- The final film has the agreed-upon length, including titles.

- The final film is in the agreed-upon format, such as 35mm.

- The film must be first-class quality.

- The film must have had the agreed-upon cast in certain roles, as well as the expected producer and director.

Why You Should Get a Lawyer

Why You Should Get a Lawyer

One of the first and most important people for you to employ is a lawyer. It is especially important to hire an entertainment lawyer, because this type of attorney will be familiar with the various kinds of contracts that are used on a production. Entertainment lawyers are also well versed in copyright laws, which will help you if you are shooting a project that is not originally yours, as well as when it comes to adding music to your picture.

You should get a lawyer for a couple of reasons. First, let’s say you do find an investor who is willing to give you money for your project. The next step is to sign an agreement between you and the investor. Do you know what kind of agreement needs to be signed? You could find a standard contract in a book and use that. Do you understand every clause in the contract? The lawyer is there to ensure that your interests are guarded, to make sure you aren’t “taken to the cleaners.”

Furthermore, some investors would prefer to work with someone who has a lawyer. Investors like to know when they are funding a project that they are dealing with someone who fully understands the laws and contracts in this situation.

Getting the Right Lawyer

Getting the right lawyer is crucial to the smooth running of any of your negotiations. Many lawyers will know the law. Many lawyers will know contracts. It is important that you find the lawyer that also suits you and your project personally. Some lawyers will charge you to sit down and talk with them first; they call this a consultation fee. Other lawyers may not charge you a fee until you agree to do work with them. If you are hiring a lawyer for the first time, make sure you hire one who is willing to work with someone with little or no experience. Your relationship with your lawyer should be based on respect and trust. At first, you want to find a lawyer who will not mind walking you through some of the contracts so you can understand them. While you should never completely entrust all decisions to your lawyer, you should be able to trust her enough for what you do not know.

Summary

Summary

The legal aspect of making films that filmmakers should know includes items such as copyright, fair use, releases, and clearances. Every production should also have insurance. This insurance guarantees compensation for loss or damage to equipment, stock, props, wardrobe, and sets. In addition, some cast must be insured in case of loss, injury, or illness. Another type of insurance is the completion bond. This bond guarantees an investor that an independent entity will either finish a troubled project or return that person’s investment. There are many contracts associated with a show, so it is wise to retain the services of a good lawyer.

References

References

“Copyright Law,” United States Copyright Office, accessed June 12, 2016, http://lcweb.loc.gov/copyright.

Peter B. Hirtle, “Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States,” Cornell University, January 3, 2016, http://copyright.cornell.edu/resources/publicdomain.cfm.

“Intellectual Property,” The Free Dictionary by Farlex, accessed June 1, 2016, http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Intellectual+Property.