In This Chapter

You want to green your products. And with all the hype surrounding green and the purchasing power of green consumers growing stronger every day, why wouldn’t you want to take advantage of the green wave? Creation of green products begins at the drawing board and design phase of the production process. By assessing the overall life cycle of your products and utilizing greener product design methods and concepts such as biomimicry, design for environment, and cradle-to-cradle design, you’ll be able to understand the environmental impacts of your products and determine the most efficient and effective means to make them greener.

Do you ever wonder if the recycled-content paper you’re purchasing as part of your green office program really has less of an impact than nonrecycled paper? How about if the fuel-efficient hybrid Prius is really better for the planet than a compact fuel-efficient vehicle? More and more consumers are asking these difficult questions and expecting product manufacturers and marketers to give them accurate answers. But just how do you compare one product or service’s environmental impact to another? As consumers become savvier and ask difficult questions about why products are green and how one product is greener than the next, manufacturers must respond with answers based on scientific data.

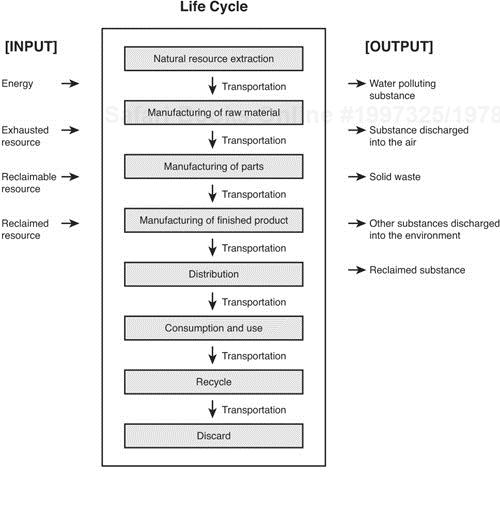

Enter life-cycle assessment (LCA). LCA assesses products and the processes used to create them from a cradle-to-grave approach. Cradle to grave begins with the gathering of raw materials either by extraction, harvest, or recovery and ends with the product disposal. This could mean land filling, composting, recycling, reusing, or any other means of product disposal. LCA analyzes all components of a product’s life cycle in an interdependent manner so that all the tabulated data relates to each stage of the product’s life cycle. This provides a complete picture of the product’s environmental impact and the ability to compare multiple product impacts. According to a report published by Science Applications International (SAIC) in conjunction with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the term life cycle refers to the major activities in the course of the product’s life span from its manufacture, use, and maintenance to its final disposal, including raw material acquisition required to manufacture the product.

Note

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) helps us understand the environmental and social impacts of a product from materials extraction to end-of-life disposal. LCA is also known as cradle-to-grave analysis.

Cradle to grave refers to the stages of a product’s life cycle, from the time natural resources are extracted from the ground and processed through each subsequent stage of manufacturing, transportation, product use, and disposal.

Conducting an LCA for your products or services has myriad benefits. An LCA can help an organization figure out the most efficient and environmentally preferable means of not only producing a product but also creating the most healthy, environmentally preferable products possible by figuring out what product inputs are not good for human or planetary health. Without a comprehensive understanding of your product’s impacts, how will you ever determine which changes are necessary to make improvements for both reduction of environmental impact and cost savings? LCA provides a systematic, interconnected picture of a product, enabling decision-makers to see what impact changing one facet of the product’s life cycle has on the product as a whole.

According to a document published by the EPA’s National Risk Management Research Laboratory (in conjunction with SAIC), the benefits of an LCA include the following:

It develops a systematic evaluation of the environmental consequences associated with a given product.

It analyzes the environmental trade-offs associated with one or more specific products/processes to help gain stakeholder (state, community, and so on) acceptance for a planned action.

It quantifies environmental releases to air, water, and land in relation to each life-cycle stage and/or major contributing process.

It assists in identifying significant shifts in environmental impacts between life-cycle stages and environmental media.

It assesses the human and ecological effects of material consumption and environmental releases to the local community, region, and world.

It compares the health and ecological impacts between two or more rival products/processes or identifies the impacts of a specific product or process.

It identifies impacts to one or more specific environmental areas of concern.

When embarking on an LCA for a product or service, you first need to scope out your project and define your goals. Assess the product or service and describe in detail the processes that go into making it. In this initial step, define the boundaries and assumptions you make when conducting your assessment so they will be clear in your final LCA report.

Next, identify and quantify all the inputs that go into making the product or service. These could include—but are not limited to—water, energy, and material use. Remember to include inputs from raw material extraction throughout disposal. Also look at the outputs or environmental releases associated with the process you are assessing. This can include emissions (including greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide), waste, pollutants, and wastewaster discharge.

Now assess the impacts of these inputs and outputs; include both environmental and human impacts. After you calculate your inputs and outputs and assess both the environmental and human impacts of each, evaluate the results and create a report. You can use this report internally to determine if you can use alternative product inputs or more efficient manufacturing practices to create a more environmentally preferable product or externally to support a green marketing story.

Example of life-cycle analysis.

(Courtesy the Ministry of the Environment, Japan)

Multiple computer programs and input databases can assist you in conducting this life-cycle analysis (see Appendix B).

This is a brief overview of how to generally conduct an LCA. But like many disciplines in the green arena, the subject is still being defined. Entire books are written on LCA, and there are international guidelines and protocols to follow when conducting your own LCA. We encourage you to dig deeper into LCA by conducting further research on the subject or contacting a consulting firm that regularly conducts these assessments to assist you.

The International Organization of Standards (ISO) developed the ISO 14040:2006 protocol for life-cycle assessment with top leaders in the field of LCA. According to ISO, “ISO 14040:2006 describes the principles and framework for life-cycle assessment (LCA), including: definition of the goal and scope of the LCA, the life-cycle inventory analysis (LCI) phase, the life-cycle impact assessment (LCIA) phase, the life-cycle interpretation phase, reporting and critical review of the LCA, limitations of the LCA, the relationship between the LCA phases, and conditions for use of value choices and optional elements.” For more information on ISO LCA protocol, visit the International Organization of Standards website at www.iso.org.

Green manufacturing provides many cost benefits: reduced cost of exotic materials, reduced waste produced by reusing and recycling materials, and increased health benefits of selecting nontoxic materials. All the measures in this chapter and throughout the book will help you increase efficiency in your manufacturing and business practices and reduce your overall operational costs, which of course leads to increased profits.

Reducing the impacts of manufacturing is an important part of greening your products. Remember, it’s important for your overall sustainability initiatives to reduce the impact of all your operations, including manufacturing. Consider developing an environmental management system such as ISO 14000 for your organization. This will help you determine and manage the environmental aspects of products and activities. Also identify lean manufacturing techniques for your industry to help reduce your environmental impact.

Product designers are turning to nature for inspiration and ideas when designing their products. This mimicking of nature is known as biomimicry. After all, not only do ecological systems operate in a symbiotic way that keeps our environment healthy and thriving, but the lessons learned from observing nature can make our products function better and last longer. Understanding and learning from these natural systems and basing human design on them will enable us to better co-exist with the species that surround us and leave less of an impact on the environment.

Note

According to Biomimicry.org, biomimicry is a new discipline that studies nature’s best ideas and then imitates these designs and processes to solve human problems.

Biomimicry looks at nature as a model, measure, and mentor. The Biomimicry Guild’s website breaks these concepts down further:

Nature as a model—. Biomimicry is a new science that studies nature’s models and then emulates these forms, process, systems, and strategies, to solve human problems sustainably. The Biomimicry Guild and its collaborators have developed a practical design tool, called the Biomimicry Design Spiral, for using nature as a model.

Nature as a measure—. Biomimicry uses an ecological standard to judge the sustainability of our innovations. After 3.8 billion years of evolution, nature has learned what works and what lasts. Nature as measure is captured in life’s principles and is embedded in the evaluate step of the Biomimicry Design Spiral.

Nature as mentor—. Biomimicry is a new way of viewing and valuing nature. It introduces an era based not on what we can extract from the natural world, but what we can learn from it.

The Biomimicry Design Spiral, a methodology which helps designers work through the ideas and framework of biomimicry when designing new products and systems, breaks down into six sections, each flowing into the other:

Identify—. Develop a design brief of the human need. In this phase, identify the problem you need to solve and the function you want your design to accomplish.

Translate—. Biologize the question; ask the design brief from nature’s perspective. In this phase, ask yourself how nature performs the function you’ve identified. What would nature do to arrive at a solution to your problem?

Observe—. Look for champions in nature who answer/resolve your challenges. Look to nature and find organisms and ecosystems you can learn from.

Abstract—. Find the repeating patterns and processes within nature that achieve success. During this process, create a “taxonomy of life’s strategies” that best solve the issue you’ve identified.

Apply—. Develop ideas and solutions based on the natural models. Apply the lessons you learned in the previous phases of the spiral to your designs.

Evaluate—. How do your ideas compare to the successful principles of nature? To create the most effective designs, we must reevaluate the effectiveness of our success.

Identify—. Develop and refine design briefs based on lessons learned from evaluation of life’s principles. Implementing what we learn in the evaluation is the key to improving our products. Just as nature evaluates and adapts, we can take this concept into our design processes.

Michael Braungart and William McDonnough published the concept of cradle-to-cradle design in their 2002 book, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. Since the debut of the book, cradle-to-cradle design has blossomed into an industry standard for sustainable design and has accompanied the C2C Certification which Braugnart and McDonnough’s firm MBDC also developed and administrates.

The basic premise behind cradle to cradle is that products should be designed so they never have to be tossed into a landfill. This is best described by MBDC’s “waste equals food” principle, which eliminates the concept of waste all together. All raw material inputs are valuable and can be reused. They are broken down into one of two categories: biological nutrients and technical nutrients.

Note

A biological nutrient is a biodegradable material posing no immediate or eventual hazard to living systems that can be used for human purposes and can safely return to the environment to feed environmental processes.

A technical nutrient is a material that remains in a closed-loop system of manufacture, reuse, and recovery (the technical metabolism), maintaining its value through many product life cycles.

At the end of its useful life, the product would either be recyclable or biodegradable depending on material inputs. Another important piece of the cradle-to-cradle concept is the elimination of hazardous and toxic substances that make up our products. If we follow the “waste equals food” mantra, this concept makes complete sense. Would you want your food contaminated with toxic and hazardous substances? No. So why should it be acceptable for products you utilize every day that will eventually be put back into our ecosystem to contain contaminants? To learn more about cradle-to-cradle design, visit www.mbdc.com.

The LCA will help you understand your product’s current environmental impact, and biomimicry and cradle-to-cradle designs will help you green your products “from the inside out.” Now let’s talk about some practical first steps you can take to make your products greener.

Ask yourself the following:

Where do the inputs used in my products originate? Can I purchase these inputs closer to my manufacturing site? This will help reduce your environmental footprint through transportation reduction.

Are any of my product inputs listed as toxic or hazardous? List your product inputs and research them to determine their impact on human health and the environment. The EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System is a great resource to use when determining the health and environmental impacts of materials. Begin phasing out the toxic and hazardous materials you use in your manufacturing processes.

Can I replace any of my product inputs with greener options? Perhaps you can utilize raw materials made from rapidly renewable resources or recycled content. Use the list you made when checking for hazardous materials to research greener, alternative inputs.

Are my products produced using green or lean manufacturing techniques? Is my company practicing sustainability internally? As our good friend Sara Gutterman, CEO of Green Builder Media, says, “You can’t produce green products from brown companies.” It is imperative, for both cost savings and marketing/branding, that you internalize your green messages.

Can I dispose of my products in an environmentally preferable manner when a consumer is no longer using them? Green products do not just mean green inputs. Remember, you must consider the entire life cycle of the product to make sure it is green.

Answering the previous questions enables you to determine the areas you need to assess and ultimately change to make your products greener. To create the greenest products possible, maximize the green benefits as much as possible.

Look at the health issues associated with your product, including negative health impacts resulting from the creation of your product. Are you emitting volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during your manufacturing process that are harming your worker’s health or discharging hazardous materials into the environment? Also consider the health impacts of your product once it is sold to consumers. This will protect your reputation as well as your bottom line.

If an ingredient, production process, or final product has questionable health concerns, ditch it. Sustainable production is based on the Precautionary Principle, a statement crafted by an international panel of scientists agreeing to prove the safety of products before they’re introduced to the market. The European Union passed this into law in 2007, and sustainable businesses worldwide abide by the premise as a basic tenet of their operations.

Creating sustainable supply-chain policies that outline your raw material purchasing goals, lean/green manufacturing goals, reduced impact distribution goals, and end-of-life product goals will keep your organization on track when greening its products. See Chapter 3 for detailed descriptions on how to lay out and write your environmental policies.

Seeking out raw materials from local sources is beneficial to your business in many ways. You’ll reduce the expense of shipping materials, which cuts down on fuel consumption and emission output. At the same time, you’ll be supporting local businesses, creating partnerships with your neighbors, and generating more local business for your own business.

Streamlining your supply chain and detailing your environmental goals in sustainable supply chain policies will improve the efficiency of your operation by reducing costs and environmental impacts associated with wasteful processes. This will also improve your green marketing messages because your organization will have a policy and plan in place to use as a guide.

Green is not the only selling point that influences a consumer’s purchasing decisions. Quality, performance, and price are three main factors consumers take into consideration when they buy a product. Look for creative ways to keep the costs of your products down, even if you end up spending a little bit more money when transitioning to green product options. Incorporating green/lean manufacturing techniques into your manufacturing process will create cost savings that you can use to balance or reduce the price of your products. Often, purchasing green inputs is less expensive than purchasing conventional product inputs. Many manufacturers who are altering their product inputs from toxic to nontoxic raw materials are seeing a decrease in disposal costs because they do not have to spend money disposing of hazardous waste.

Utilizing alternative and less-toxic materials to create your products are both ways to create a greener product. Greening what you put into your product is a surefire way to reduce your product’s environmental impact. For example, if your product inputs consist of toxic components that emit VOCs, the end product you produce will not be green. As you learn more about toxic materials, you can ensure that your products are toxin-free and more sustainable.

When possible, increase the amount of recycled materials used in the production of your product. Using recycled materials as raw material inputs creates new markets for waste and encourages recycling. If there wasn’t a commodity market for that milk jug you are throwing into the recycling bin, would your recycling program exist in the first place? If we do not encourage the use of recycled content in new products by incorporating it into our product manufacturing processes and purchasing goods composed of recycled content, we jeopardize our recycling systems.

Going Green

You can seek eco-label certifications from third-party organizations to provide your customers with “seals of approval.” See Chapter 22 for a review of eco-label certifications you may wish to consider applying for.

An example of positive market development through the use of recycled goods is The California Resource Recovery Association’s Polystyrene Recycling Market Development Zone program. The California Resource Recovery Board teamed up with local municipalities and Timbron International, a manufacturer of products made from recycled polystyrene, to create a market for recycled polystyrene (or Styrofoam as it is commonly called). This plastic is typically known as a “difficult to recycle” plastic because it’s not commonly recycled.

The Association created a pilot recycling project that allowed counties surrounding Timbron’s facility to recycle the plastic by organizing a logistical system that delivered the recycled polystyrene to Timbron for reprocessing and new product manufacturing. The end result was that the participating counties decreased the amount of waste they sent to the landfill, and Timbron International made their products greener by increasing the amount of local recycled material in their product. Currently, Timbron International also participates in pilot polystyrene recycling programs with the cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Timbron’s story is a prime example of how a business can work with their local government to find solutions to waste problems. The community benefits because its waste is reduced and recycled, and the manufacturer benefits because it receives local and lower-cost materials.

This is just one example of new markets we can generate through the use and creation of recycled products. The ability to create products from recycled content is not limited to plastic; we have seen products composed of recycled glass, aluminum, wood, chewing gum wrappers, tires, blue jeans, and paint.

Preventing pollution during your manufacturing process saves your organization money and further backs up your green story. The first step to pollution reduction is understanding where and how you are polluting. Create an inventory of all pollution points associated with your manufacturing operation. Look at sources of air, water, land, noise, thermal, and light pollution. After you determine all points of pollution, take strides to reduce each source you’ve located.

Solvent usage is an essential part of most manufacturing processes. According to SRI Consulting, the annual global consumption of solvents is estimated at 30 billion pounds per year, and consumption in the United States alone is in excess of 8.4 billion pounds per year. Users of petroleum-based solvents are feeling more pressure than ever before from regulators to reduce the environmental impacts associated with solvent use. This includes emission reduction, improper disposal, and reduced use. Swapping petroleum-based solvents with bio-based options is an easy way to reduce the environmental impact of your manufacturing operations and to prepare you for current and future regulatory requirements.

Bio-based solvents are made from a renewable agriculture source such as corn or soybeans and emit less VOCs than petroleum-based solvents. Oftentimes bio-based solvents are biodegradable and are less toxic, creating a healthier workplace for your employees through both improved indoor air quality and reduced contact with toxic chemicals. In addition to environmental and employee health benefits, bio-based solvents often perform better than conventional solvents.

Going Green

According to the Ohio EPA, bio-based solvents have a lower environmental impact—they have low toxicity and high biodegradability. Also, lower VOCs and less pollution are generated during the manufacture of a bio-based product than a petrochemically based product. Increased business advantages of using bio-based solvents include reduced disposal costs, improved worker safety, and the ability to market “green consumerism.”

After you have improved the energy efficiency of your operations and reduced your emissions as much as possible, you can purchase renewable energy credits to offset your remaining emissions if you have first determined your carbon footprint (see Chapter 6).