2. A Critical Few Traits

SCENE: March of the same year. Alex’s office.

KATZ: You look a bit glum. What’s wrong?

ALEX: I just finished conducting an exit interview with one of our best people, a young buyer named Calvin.

KATZ: That’s disappointing. What did you like about him, and why is he leaving?

ALEX: Calvin’s ambitious, with great business instincts. He focused on growth goals—both for his product group and for the whole retail chain. He built relationships with some new suppliers in Europe, really interesting merchandise. One of them offered him a job, and he told me yesterday that he’ll move to Germany and join them. He said the pay would be a bit more, but mainly he talked about how flexible they seemed, how much autonomy and direction he would have.

KATZ: Why did he talk to you instead of his direct boss?

Were there issues there?

ALEX: Not at all—he reports to the head of supply chain, Florence, and they thought the world of each other. And Trans, our head of technology, is another one of his mentors. But I wanted to talk to him as well to find out more. I have a slush fund in my budget for a special projects role, and I thought I might be able to talk him into a rotation as my direct report. But he seemed determined to go.

KATZ: What did you learn?

ALEX: That he was fed up—not with Florence or with anyone in particular, but what he called “the bureaucracy.” He said there were just too many barriers to doing his job.

KATZ: Are internal operations typically a problem?

ALEX: Yes and no. From an operating model standpoint, we have best practices in place that I’ll match against any other retail chain—in HR, IT, marketing, you name it. And we’re always under budget. But somehow we still don’t see results. On paper we are doing everything right, but just walk around and people will tell you how much is broken.

KATZ: Tell me more. What’s an issue people tend to complain about?

ALEX: Well, the purchasing group always has a bone to pick about our travel policies. Like most retail companies, we aim for pretty lean operations, and this includes a policy that anyone below VP level fly economy. This is fine for domestic flights. It’s tough for Europe, though, and murderous for Asia! And the purchasing team, who are all below VP, are the ones whom the policy hits hard because most of our suppliers are outside the US. Imagine that you’re on that team. A few times, you probably do the right thing and fly to China to meet with vendors. But navigating those relationships on a different continent on just a few hours of sleep is really tough. We’ve noticed that these trips are happening less and less, and who can blame them? We save a few thousand on airfare each time that they travel, but overall the company ends up shortchanged.

KATZ: How so?

ALEX: Our product mix this season looks a little lackluster. I’m beginning to conclude that the purchasing group would have made better decisions if they had felt more supported in their efforts to go the extra mile to uncover better options. I’m frustrated because I feel like I shouldn’t have to be the one to tell people when to bend a rule and why—I want them to have better judgment!

KATZ: What else are you seeing?

ALEX: It struck me the other day that our marketing group also has fallen into some ways of working that might be getting in the way of our goals. Everything they produce is perfect before it goes out the door. That’s hard to complain about, right? But a ton of material is written that nobody ever sees. Or we hit a trend two months too late and everyone wonders why we missed the boat. I tried to raise this with Avery, the head of marketing, and he looked horrified. It was like I was trying to get his team to lower their standards instead of trying to work more efficiently. The ways that people work, the things that they congratulate themselves on having achieved—a perfect, flawless document—are at odds with how I believe we need to operate to beat our competitors.

KATZ: That’s a great example. It’s not that, per se, perfectionism is a bad quality. There are situations when striving for perfectionism can save everybody from costly mistakes. But there are also situations where the perfectionist habits slow things down, keep people feeling bogged down and frustrated, like they can’t accomplish what they are being asked to do—a feeling we describe, in my line of work, as one of the symptoms of “cultural incoherence.” But don’t worry—the lecture isn’t starting yet. Go on. What else is on your mind?

ALEX: There’s the problem of waste. We have as many problems with environmental compliance as any company with brick-and-mortar locations. But we could cut significant cost and materials, and save money in the bargain, if we had a more comprehensive waste-reduction program. One-off ideas pop up—like installing motion-sensor lights in break rooms, having drivers turn off trucks instead of letting them idle to save on fuel costs— but nothing ever seems to stick or gain momentum. We never take ideas far enough to see real results.

KATZ: Do the functional leaders talk to each other about these problems?

ALEX: Not much. They are all at different places. For example, in people practices, some of our leaders are really good at motivating their groups. Others beat down their people and push hard with threats. We don’t have any discussion about which approach works best for us—or even when each approach is most appropriate. My gut tells me that the former is more effective than the latter—after all, it was you who taught me that pride matters more than money, and certainly more than stern lectures. [At this, Katz smiles.] But I don’t have any data to back that up. Before I confront the leaders who have the reputation of being really hard drivers, I want data to make my case. Until I get that, it’s a lot of rumors and anecdotes without any real specific examples of what works and why.

KATZ: Have you talked to different functional leaders about, well, inviting each other to meetings and confronting these problems more openly and directly?

ALEX: I’ve made some strong suggestions, and my heads look at me like, “You’ve got to be kidding!” I feel like I need to be really specific; if I try to just say, “Hey, everybody, start working together,” I’m sure that I’ll be ignored. For example, marketing and IT need to jointly develop a customer analytics system; we’re capturing the data at the stores and online, but as yet we have no real system that lets us pull out any useful insights. But both sides have been holding back on saying what they can offer. They seem more concerned with protecting their turf than making a new idea happen. Meanwhile, the finance department can send in a budget, and then accounts payable won’t sign off on it. Weeks of work by the finance team squandered, decisions stalled. It’s ridiculous. But truly, I can’t step into every decision and interaction.

KATZ: And let me guess. Your leaders say that they can’t behave differently because of obstacles and attitudes embedded in the system. Secretly meaning there’s no reward, it doesn’t help them move up the ladder, or others will get in the way. Basically, it is just not worth the time.

ALEX: Yeah. And there are some real bureaucratic obstacles, such as having to get permission to even talk to someone else’s supplier. Some of this has to do with rivalries, fiefdoms, fights over turf. People believe that they’re all vying for the same funds, even when that isn’t true, even when they pull from separate parts of the overall budget. At times I suspect there’s some backstory no one will tell me, happening years before I came on the scene, that has led to alliances and grudges I’ll never understand. But I refuse to believe that unearthing old stories will fix what’s broken. I’m ready to just yell out, “Everybody get over it!”

KATZ: And the biggest factor in your favor is that most everyone cares about the company in one way or another—right?

ALEX: Yes, they absolutely care about the company. They just aren’t sure how they feel about each other.

KATZ: [Laughs] Well, I have some good news for you.

ALEX: I could use some.

KATZ: Last time we met, I said that I didn’t think your company was too bad off compared to others I’ve seen. I still believe that. Even the complaints and fights can give you some reason to be hopeful. Frustration is on the opposite end of the spectrum from apathy, which is the most dangerous condition in any organization. Frustration suggests that people want to see change; they’re aware that there are problems. They’re blaming each other—or “the system” in general—because they don’t see a clear path forward. And since their emotions are involved, you can’t just tell them what to do. You have to make them see and actually anticipate feeling good about taking advantage of their common interest.

ALEX: I’ll get right on it. I’ll have a memo out to them tomorrow.

KATZ: [Laughs] What are you really doing about it?

ALEX: Well, I already sat down with our head of HR, Elin. She’s a fixture here; she started her career under Martin, the CEO who preceded Toby. She told me about a “values” exercise that the organization went through seven or eight years ago. That wasn’t too long before I began working here, but I told her I’ve never heard anyone mention the values in my conversations with people across the company, including the former CEO! Elin wants to revisit and refresh the values for a new era, but I’m skeptical about what that would accomplish.

KATZ: Values—what an organization stands for—ab solutely have a part in this discussion, but I agree with your instinct that the conversation about culture can’t begin and end there. However, let’s back up a little. Tell me more about these conversations you’ve been having with people.

[At this, Alex brightens.]

ALEX: The last conversation I had with you, in January, really encouraged me to continue, and even expand, the efforts I’ve been making to have one-on-one or informal small group conversations. Not just with department heads but employees all across the company. I asked my assistant to expand every scheduled distribution site visit from a half day to a full day and kept the second half of the day clear so I could just wander around and talk to people one-on-one. I also make every effort to take hierarchy and authority out of the room during these discussions, although I know that is hard to do. Make sure everybody calls me by my first name—that’s always a good start.

KATZ: [Nods approvingly] What are you hearing?

ALEX: When we last met, you pushed me to understand Intrepid on its own terms. So I’ve been asking people to describe the company: “What is it about us that makes us special?” “What does Intrepid mean to you?” But I have to confess, I didn’t get very far. People seemed a little flummoxed by the questions—one person even took out our marketing materials and talked me through our tagline and mission statement, as if I’d never seen them before! [They both laugh.]

KATZ: That was a terrific start. And I’m also not surprised to hear that you spun in circles a little, and I’m glad we’re meeting again.

To develop an accurate sense of your culture, the set of habits and behaviors and beliefs that determine how work gets done, you have to be a little indirect. Most of the time, as you just experienced, people seem to get overwhelmed by the culture topic—it feels too unwieldy to put into words. Instead it helps to keep conversations focused on behaviors—real, observable, tangible behaviors, things that people do every day in the course of going about the daily business of their work. And then you will stay alert to when these behaviors elicit some kind of emotional response, negative as well as positive. That emotional response tells you that those behaviors are touching on, catalyzing, generating—or getting in the way of—a sense of connectedness between people.

And you don’t just ask the top few layers—or even necessarily start at the top, although you do want to keep the top team involved. You go through the company, and you pull together some discussion groups at different levels. You ask about strengths and weaknesses and start to build a picture. For instance, you might ask, “What do you tell neighbors at a weekend barbecue about why you like working at Intrepid?” “What does your best day look like?” “When are you excited to go to work?” “What do you tell your spouse when you don’t want to go to work?” “What keeps you up with worry at night?” From these conversations, and from other data points that turn up along the way—the “official” ones, like employee surveys and the values statements you mentioned, as well as “unofficial” ones, like shared jokes that everybody seems to know—you start to build a much more realistic picture of Intrepid’s culture challenges and opportunities. It’s just like developing your business strategy. The final product should be simple: a list of core traits that are accessible to all, a language that everyone can understand. But it takes a lot of input and iterations to get it right.

ALEX: What’s an example of a trait? Would it be something like integrity?

KATZ: No, I wouldn’t call integrity a trait. Integrity is a value— something we aspire to. If I believe that I work in an organization that has integrity, that belief gives meaning and purpose to my work. It strengthens my emotional connection to the others around me. Values, when well articulated and demonstrated, do this very well—they give us something to aspire to. But it’s hard to connect a conversation about values to the real work that people do every day, except in very ideal terms. And values don’t make much of a difference in performance until they are reflected in what highly respected people do as a result.

ALEX: [Looking thoughtful] Or unless a value seems to be missing. I had to fire someone for stepping out of line last year, related to integrity.

KATZ: I’m sorry to hear that—but that’s correct. And it underscores what I’m saying. Values are necessary and are also aspirational. Like strategy, they are always out ahead of us—they are what we are trying to achieve. Establishing values, and using them as touchstones to remind us all how to be our best selves, is a crucial part of any effort to work on culture. But values alone don’t define a culture. Values reflect how you want things to be done; traits reflect how things are done today.

ALEX: So if integrity is a value, tell me about a trait. What’s a trait you see at Intrepid?

KATZ: I’ll use your own words. You’ve described the company to me as thrifty and very process focused: these are perfect examples of traits. A trait is a tendency to work in a certain way. It ties directly to performance. And crucially, it’s neutral—you can see how sometimes it helps the business and sometimes it gets in the way. We’ve all worked with someone who followed every process to the letter and still wasn’t deemed high potential and put on the fast track to manager. Being process driven has both strengths and weaknesses. And when you get people to talk about that, you can start to have conversations about culture that feel like they might lead to real change.

ALEX: It’s interesting that you mention both strengths and weaknesses. Why weaknesses? You seem to encourage that I take a very positive view of Intrepid’s culture. Wouldn’t you, then, encourage me just to focus on its strengths?

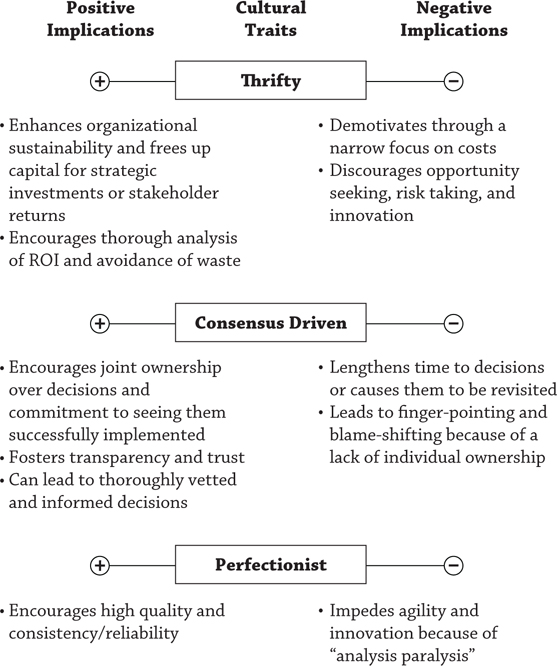

KATZ: Strengths and weaknesses are two sides of the same coin. If you can’t recognize the weak side of a trait, its potential downside, then you aren’t looking at the whole picture. Most importantly, you miss the full set of emotions people have around a trait—the sense of accomplishment and pride that people in a thrifty organization feel when they stay within budget and find clever ways to save resources, as well as the exasperation and annoyance that they feel when they sense that others are shortchanging them, being penny-wise and pound-foolish. Traits are both sources of energy and potential obstacles to what you need to do to succeed. You have to name and recognize them to be able to deal with them in all their complexity.

ALEX: Can I change the company’s traits?

KATZ: It’s so much easier to work with what you have than to try to change the fundamental nature of your organization. Let’s stay with thrift as an example. In an industry with margins as tight as yours, you’d be a fool to try to get rid of it, right? What you need to do is acknowledge it, reward it where it helps you, and point out where it gets in the way.

ALEX: Are you saying that I can’t change Intrepid?

KATZ: No, that isn’t what I’m saying. But here’s the bad news: major change will be slower than you want it to be—it can take decades versus months or years. That’s why I refer to it as “evolution.” But if you commit and are consistent, evolution also can be real and lasting. That’s the secret that the best leaders know, and that’s what I’d like to help you accomplish.

ALEX: It’s frustrating to hear that change is slow. But at the same time, I’ve never heard anyone tell the story of an organization or institution that changed overnight. I believe what I’m hearing. Let’s try it your way. Given the complexity, where do you suggest we start?

KATZ: When’s your next leadership team meeting?

ALEX: Mid-May.

KATZ: Great, that gives us some time to be purposeful about how you engage them. I think that the values exercise that Elin suggested is a good idea. If Elin brought it up, she is surely seeking a way to help you align key emotional elements of your cultural situation, and that’s the tool she’s familiar with. So let’s make that the window we move through. It’s a good enough place to begin.

Then, that leadership team meeting can be a chance to engage the other executives on the topic of culture more broadly. In the interim, why don’t you name Elin and a few others to help you, and together you can run some interviews of the type that I described. Give Florence a call—if she sees the link between Intrepid’s culture and the loss of one of her best people, Calvin, she’ll be motivated to work with us to try to see what’s going on.

From those interviews, we can develop at least a rough draft version of what Intrepid’s traits might be. A conversation about values, what you aspire to, is an excellent time to also talk about who you are as a company, how you work every day.

ALEX: Florence is just down the hall—I’ll go talk to her now.

And I like your use of “we.” I suppose this means you’re offering to help?

KATZ: [Smiles] Well, I can’t think of anything I’d rather do.

WHAT ARE TRAITS, AND WHY ARE THEY IMPORTANT TO CULTURE?

Traits are at the heart of any organization. They are the essential characteristics that form the scaffolding for how any group of people thinks, feels, and behaves. They are the stable, prominent qualities that are shared across a company. For any leader who seeks to understand a business’s cultural challenges and how it operates, it’s important to start by surfacing and articulating these critical few traits. The process of doing so—the diagnosis, the self-reflection, and the narrowing down—is a crucial first step to both evolving and aligning an organization’s cultural influence on how people behave to get things done emotionally as well as rationally in any organization—the cultural insight step described in chapter 1.

Why do the traits matter? Let’s start with an analogy—in fact, let’s start by considering Alex himself, who is (we hope) becoming clearer to you as a person over the course of this story. Alex has values that he holds dear, like taking care of the people he works with and behaving with integrity. These values have resonance for him and are ideals he aspires to consistently meet, ways that he likes to think about himself, his colleagues, and his goals. Alex also has a core set of personality traits, such as self-confidence and ambition. These are so essential to Alex that they might not even be clear to him—they are like the bones beneath his skin, the fundamental matter of which Alex is made. If you wanted Alex to change or evolve in some way—let’s say that, for the good of his company, you wanted Alex to have more conversations with his leadership team and spend less time scrutinizing numbers that could just as ably be overseen by his CFO—you would be wise to understand and build from not just the values Alex aspires to but also several of the key personality, character, and gender traits that now govern how he acts day to day. Any efforts to understand, work with, and even evolve Alex as a person must begin with an understanding of these traits and an acceptance that they’ll be slow to change.

Are we implying that people (and, by analogy, organizations or organizational culture) can’t be changed? Let’s emphasize the answer here—this is a crucial point at the heart of this methodology. Organizations can change (or, rather, evolve)—but only if that change is grounded in a solid sense of the steady state of that organization. It is well documented that most organization-wide attempts at changing culture fall short of the original intent; as we noted in chapter 1, one quarter of the Katzenbach Center survey respondents reported that an effort had been made to change their company’s culture and that they had seen no difference whatsoever as a result. This “failure to budge” on the part of culture is due to leaders’ skipping the “traits” step—that is, refusing to surface, articulate, and commit to working with their organization’s core differentiating qualities. It is a result of jumping to solutions without pausing for self-reflection and diagnosis.

A client once told Gretchen a story of how he had interviewed at a moribund retail giant, a well-known organization whose brand reputation and profitability had been on a slow decline for decades. The client, Jeff, was interviewed by the newly minted CEO for a role on the turnaround- focused leadership team. According to Jeff, the CEO explained his strategy this way: within a year, he expected to redefine this large, slow-moving, steady-ship retailer as a technology innovation company. Jeff hightailed it out the door rather than waiting for an offer. He was wise to do so. (And the fact that he told Gretchen this story as a laugh line made it clear to her, right away, that they would work well together.)

A quick change toward what’s trendy isn’t wise or even possible. Leaders must begin with a solid understanding of where they are today, what “family resemblance” exists across the company. Then and only then is it possible to focus on behaviors that bring out the best, most useful aspects of these core qualities—and to encourage more of them, every day.

Recall one of Alex’s core traits: ambition. Unlike his value of integrity, which is inarguably positive and aspirational, ambition is neutral. You can imagine scenarios in which Alex’s ambition is useful to him as an individual and to the organization he leads. You can also picture certain days or certain situations in which this same quality causes those around Alex to roll their eyes in exasperation. Now imagine that you were Alex’s executive coach. You would likely point out that he can’t change the central fact of his own ambitiousness— but he can recognize and repeat the best behaviors through which it manifests, like encouraging others to set high goals. You could also teach him to notice and curb ambition-related behaviors that are less productive, like demonstrating impatience with others who are slower learners.

Similarly, in our work with organizations on culture, we strive to help people see their organization’s essential traits as neutral—which does not mean that they are bland and nondescript. A trait’s neutrality means that it has positive and negative repercussions. Traits also have an emotional component. When we work with organizations to deduce and define their core traits, this process always involves working through strong feelings that people have about the institution that they are part of, about how it supports them and when it feels like it stands in their way. Getting to a neutral, clear-eyed diagnostic means working through a lot of emotional nuance. Then, when the traits are presented back to the organization, another kind of emotional response occurs: the satisfying sense of recognition of commonality and the pleasure of being seen and understood.

Arriving At your trAits

You won’t be able to arrive at an accurate, emotionally resonant group of traits by asking only a few people. You’ll want to engage groups of people at different levels across the organization in structured interviews and focus groups designed to surface their feelings about your organization’s culture. There are many ways to approach these interactions; in the appendix, you’ll find a sample focus group agenda and sample interview questions to spur your thinking.

Exhibit 2.1 lists twelve common traits from the many we’ve collected through our decades of research and client work. Don’t be constrained by this list, however—it’s provided just to give you ideas. A trait that describes ways of working at your organization may be one that is unique to your company. For example, we conducted a client diagnostic at an organization in which people loved to tell stories about the company’s origin; “respect for folklore” ended up as one of its core traits. Although one could imagine how respect for folklore could get in the way of some strategic aspirations, such as innovation, it also had very deep emotional resonance for people at all levels—and we’ll be surprised if it appears on a list of traits at any of our other clients.

• Consensus driven |

• Cautious |

• Caring |

• “Above and beyond” |

• Hierarchical |

• Process focused |

• Individualistic |

• Opportunistic |

• Relationship focused |

• Optimistic |

• Paternalistic |

• Egalitarian |

Exhibit 2.1 Examples of traits from our work

At a high level in the organization, the best approach to surfacing good data is to avoid direct questions, such as, “What traits are important in our culture?” As with Alex’s first effort with his own employees, that kind of direct approach is likely to yield only platitudes. Instead, get people to tell stories about what’s important to them. Ask what they love about coming to work, what they are proud of regarding the way that they work together, decide, and motivate. Stage some of these conversations as one-on-one interviews and others as small, informal peer groupings. You’ll be surprised and delighted to hear what emerges from eight or ten people who are encouraged to share their thoughts in an appropriate, safe environment. Exhibit 2.2 is a sample of questions we have used at client engagements to spur this type of dialogue.

Also ask people what frustrates them at work. Individuals may take this opportunity to vent. Allow this, but direct the conversation away from common day-to-day complaints that are applicable to any corporate environment and focus on qualities and patterns of behavior that are unique to the organization. If guided in this direction, individuals usually realize that many of the things that frustrate them are the flip side of the things they are proud of. You may hear something like, “We really care about our people, and sometimes that means we make the ‘caring’ decision rather than the ‘right’ decision.”

|

|

General |

What are the strengths in your culture—what makes you most proud to work here? |

What elements of your culture (e.g., the way things really get done at your company) get in the way? |

|

Decision-Making |

Who makes decisions? Do decisions tend to be made by one person or via consensus? |

Do people here tend to rely more on data and analytics in decision-making or intuition and experience? |

|

Motivators |

How important are external customers relative to internal operations? |

Is this a place where people tend to come and stay for life, or is attrition common and expected? |

|

Do people here tend to be more interested in history or what the future holds? |

|

Attitudes |

Is your company made up of experts or generalists? |

How tolerant of risk are people in this company? |

|

What is more important—self-sufficiency or collaboration? |

|

Process and Structure |

How hierarchical is your company? Are all voices treated equally, or do people defer to leaders? |

How rigid are processes? Is improvisation allowed and encouraged? |

Exhibit 2.2 Sample questions

Even if the folks you speak with don’t make that explicit connection, you will often find that the challenges and frustrations they describe stem from sources of pride. For example, individuals working at organizations that prize individual empowerment and autonomy often express exasperation at how hard it is to get anything done that requires coordination or standardization. A common complaint is “Everybody thinks all the people here are special and wants to be granted an exemption from the rules.” On the other hand, people working at highly collaborative, consensus-based organizations can be proud of having a voice in every decision that impacts them but also frustrated by the amount of time it takes to get everyone to agree.

Inevitably, subculture traits will appear. This is natural and logical. For example, traits will emerge that are more prevalent in HR and less prevalent in the finance team, like “people focused.” Traits like “safety conscious” will emerge in focus groups with employees on the shop floor but never in marketing. And subcultures aren’t limited to functions. Throughout the decades that we have worked in this field, we have seen an increasing trend toward globalization of large multinational organizations. Most of the companies we work with now have subcultures that cross real boundaries; potential frictions are enhanced by acute differences in language, style of dress, and even religious faith and alphabet. But do not let the presence of strong, differentiated subcultures distract you from the task of surfacing and identifying overarching traits. Our clients have included global organizations with regional offices that spanned continents and behemoth companies cobbled together by ambitious acquisitions. In every situation, a patient and thorough diagnostic has surfaced traits that were, to the surprise and agreement of all, common and consistent across the full span of the organization.

In addition to interviews and focus groups, other methods and data points can help you enrich your understanding of your culture. The Katzenbach Center team deploys a survey tool that highlights the relative prominence of traits that tend to recur across organizations, but this specific tool is not the only way to crack this nut. Many organizations conduct internal employee engagement surveys. Within our own firm, PwC, the Saratoga Institute developed one of the first consistent sets of HR metrics forty years ago and now has a cross-sector, global database through which organizations can explore how their people-related data compares to that of thousands of other companies across the globe. Whether an organization has an internal, homegrown survey that has been conducted just a few times or has a large annual survey with rigorous external benchmarking that has been done for many years, a common complaint we hear from clients is that survey results do not lead to change. But we encourage them, as we encourage you here, to take out the results and dust them off. It’s all good data and can help yield the types of insights you need. Brainstorm with your trusted advisors and with thought-provoking outsiders—one company we work with actually used data from exit interviews with employees who had decided to leave, and this helped leaders pinpoint, discuss, and finally address a culture trait of bureaucracy that had bedeviled them for decades.

Whatever method you use to gather insights about your company’s traits, compare the results with your own observations. Watch people in meetings, in casual conversations, and in their daily operations. Consider the surroundings as an outsider would see them: What do people display on their desks? Are the plants being watered? What are the artifacts on the walls? Observe whether people move quickly or slowly to make decisions and consider what either accelerates or impedes this process. Ask yourself whether meetings are more effusive or matter-of-fact and if that is a common preference throughout the company. Is your company naturally global in outlook, mixing people from different nationalities and backgrounds, or does it tend to remain active within just one territory or region? Does the leadership team always meet at headquarters, or do they travel to other regions? What do your people care about? What motivates them? What do they do in the workplace that they wouldn’t elsewhere?

Here are some examples of observable detail from many decades of walking onto corporate campuses and beginning to discern a story about culture. Twenty-five years ago, Apple chose to name the main U-shaped drive of its headquarters campus Infinite Loop, a coding term. This playful approach was very unusual at the time, signifying a lack of propriety. Decades later, though, an irreverent (and even indulgent) approach to office space, including whimsical details like slides and scooters and perks such as free snacks and dry cleaning, has become almost an industry norm in the technology sector.

Danaher’s unprepossessing offices, in the heart of Washington, DC, say that the company, while plugged into a vibrant capital city and its businesses, is resolutely unpretentious and pragmatic. A cafeteria full of lush, fresh produce and vegetarian options at a pharmaceutical company we worked with signaled a broad commitment to health and wellness. Bare-bones supply closets at a midstream energy company in Houston that had just acquired a much more extravagant (and less profitable) competitor demonstrated the core trait of extreme efficiency and thrift. At this last company, one of our consultants asked to borrow a gum eraser from an administrative assistant. The admin smiled graciously, took a large pair of scissors and a worn-down eraser out of her desk drawer, sliced that eraser in half, and handed the consultant the larger slice. It’s hard to find a better example of how a real-time behavior manifests a core trait!

The goal of this detective work is to generate a list of culture traits that is unique to the organization and to understand the positives and negatives associated with these traits. You can think of a company’s traits as a list of neutral descriptors, with positive manifestations (or sources of strength) on one side and negative manifestations (or challenges and barriers) on the other. For example, you may have a company that is consensus driven, in which the entire team feels ownership of decisions. This may be a valuable trait for your company because it can ensure that once a decision has been made, many people will come on board to help execute it. On the flip side, if decisions can’t be made without consensus, it’s very hard for an organization to act. Further, ideas can be watered down to the lowest common denominator, the least offensive one, because conflicting points of view are too threatening. Articulate all of this. The more specific you can be about the real behaviors related to a trait, the better it will be for developing an accurate picture of how this trait manifests at your company.

After you develop a “long list” of traits, select three to five key traits that best articulate your company’s current cultural situation. Choose carefully, because the traits will be a touchstone in the process of evolving your culture. Traits describe, with emotional resonance, “who we are” on our best days and on our worst. To be most useful, these traits need to meet several criteria, as shown in exhibit 2.3.

Traits should

• Reflect your company’s essential nature. People throughout the company should be able to recognize the traits as meaningful; there should be broad agreement that they articulate some core essence of how people work together.

• Resonate across the enterprise. These traits are not just for the engineers, the people in your home country, or the people at the top of the hierarchy. They should feel relevant to most people, even though the behavioral manifestations of one or more traits may differ across subcultures, functions, or geographics.

• Trigger a positive emotional response. The positives associated with the traits should be things that get people excited and that all agree will lead to a better, more effective business. Make sure the traits trigger enthusiasm for and commitment to the company’s goals and that they can keep motivating your people over time.

• Support your company’s cause. You began this culture effort for the sake of moving your company in a new direction: to be more resilient, to face an external threat, or to move toward an opportunity. The traits you select should have implications that are relevant for the direction you are trying to go in. The strengths should be sources of emotional energy that support your business goals, while the challenges are typically barriers that are holding you back.

Exhibit 2.3 Selection criteria for critical traits

Exhibit 2.4 is a sample “traits analysis” that we created, over the course of writing this book, for our fictional company, Intrepid. In the next chapter’s episode of the Alex and Katz story (spoiler alert!), our estimable (and imaginary) Intrepid culture team will choose three core traits for their company: perfectionist, consensus driven, and thrifty. As part of the exercise of writing the fictionalized Intrepid case study, we pulled together a team of our practitioners, and we all brainstormed behaviors that would manifest the positive and negative sides of these traits, just as we do with our clients. Usually, this kind of analysis takes weeks of conversations, but for our purposes, we just did it over lunch. (People who work with us tend to call this kind of activity “fun”—lucky for us!) When we do this analysis with clients, we call it a “culture thumbprint.” The example in exhibit 2.4 is the result of that lunchtime brainstorm. It is a good proxy for one of our clients’ analyses (which are usually too intimate to be shared outside the company).

FROM TRAITS TO EMOTIONAL COMMITMENT

Emotional, irrational, messy human responses—their attach ments, triggers, affiliations, identifications, resistance— are at the heart of any discussion on culture. Katz’s 2003 book, Why Pride Matters More Than Money, posits that the best leaders and organizations in the world have succeeded due to their ability to cultivate pride in people. Katz argues that “leaders at any level who develop the capability to instill pride in others can use that ability to achieve higher levels of business performance.” This was premised on the two-factor theory of job satisfaction of American psychologist Frederick Herzberg, who coined the term motivational factors for intangible forces that encourage good performance. One of Herzberg’s notable conclusions, surprising at the time but now accepted as truth (and argued by current notables such as Daniel Pink), is the idea that work itself can serve as a motivator. In 1968, Herzberg published an article, now a Harvard Business Review all-time classic, titled “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” The answer to his question is Herzberg’s core message, which he re peated many times throughout his life: you motivate employees through the work itself! This is a fundamental belief of Katz’s as well, and it’s consistent with how we now approach cultural alignment organization-wide. To motivate either an individual or an organization, you must closely observe what is happening well and encourage more of it. Emotional commitment flourishes when it is nurtured from seeds within, not applied according to some frame or set of standards that are external to the company.

In the decade and a half since writing Why Pride Matters, Katz has continued to believe in its central premise, but he is also more interested in a broader range of emotions. Simultaneously, through the Katzenbach Center’s research and client work, we have developed a method and structure to the process by which leaders can draw a bright line for people between how they feel about their work and how their work supports their organization’s overall strategy and goals. And surfacing and defining an organization’s traits is a necessary step to releasing those powerful emotions, to drawing that line.

But wait, you might say—so much of this chapter has been devoted to the idea of traits as neutral. Can traits be both neutral and emotionally resonant at once? After all, how possible is it to get misty-eyed about a term like performance driven? Nevertheless, time and again, we witness organizations as they move through the journey of a culture diagnostic and arrive at their traits—and we learn each time that this is truly a process of trying to apply precision and discipline to, paradoxically, open up a space for that which is imprecise and undisciplined—the emotional aspect, the nonrational, noncompliance-oriented aspects of the culture. Why is this?

Emotional energy is released as traits (and behaviors, the topic of the next chapter) are defined because traits, when well-articulated, reinforce and remind people within an organization of their sense of belonging to something larger than themselves. At the beginning of a culture diagnostic, leaders of a client organization often express skepticism that they will be able to uncover any common traits—they believe that their organization, unlike any other, is composed of subcultures so strong and unique that they have nothing in common but the font on their business cards and the name of the company on the letterhead. And then time and again, as we listen, assess, evaluate, and discuss, we are able to come up with some strong, resonant traits. And the members of the subcultures who had understood themselves as being so divided are able to nod their heads and say yes, we agree, that is just how we are. They are also able to recognize, in both the traits and behaviors, their own language that they use to describe themselves.

In recent years, we conducted a culture diagnostic for a North America–based energy company and arrived at the following four traits: consensus seeking, loyal to the com pany, relationship driven, and respectful of expertise. Can you guess which one catalyzed the most friction in the process of getting to agreement? It was the driest, least “relationship” focused: respectful of expertise. Within this organization, this quality was so dyed-in-the-wool and valued, it was difficult to hypothesize about its neutrality. In other words, leaders were so convinced that their experts were always right, they almost couldn’t stand any conversation implying that they could be wrong!

Over the course of a few hours of good dialogue, however—supported by great, real examples that we’d surfaced through the diagnostic, like the story of a functional leader who’d reduced a subordinate to tears for posing a question that challenged her technical opinion—we were able to help the whole leadership team agree that certain habits and behaviors associated with “respectful of expertise” were indeed getting in the way of the business agenda. Here is what we repeated, over and over, throughout that conversation with the team: We were not trying to get rid of the cultural tendency to value experts—we couldn’t root it out even if we tried! We were simply trying to help raise an awareness of it as a trait so that leaders could, going forward, have real conversations about when and how it got in the way.

And sometimes, a relatively neutral-sounding trait has emotional resonance that an individual applies again and again over the course of his or her career. Kate Dugan, one of our Katzenbach Center core team members, began her career at Strategy& in the days when it was Booz & Company. Firm members at the former Booz & Company shared a very hardwork ethos; even partners at the highest level did not hesitate to dig into numbers and format PowerPoint documents side by side with more junior team members. A well-defined, popularly acknowledged trait of this firm was “sleeves rolled up.” It was a phrase that connoted, for members of the firm, both an approach and a set of observable, real behaviors, like staying up late, tackling hard problems, and taking pleasure in real hands-on work. As a new consultant, Kate liked this phrase very much; she thought it represented one of the best qualities of the firm and how people behaved together as a team at their finest moments. As Kate described it, the way that she learned to do real work was influenced and inspired by that phrase. Even more significantly, she mentioned that a partner had once persuaded her to do something she was afraid of, facilitating a senior meeting on her own, by using that phrase. It had emotional resonance that helped her connect a new, slightly intimidating behavior to a quality that she liked to believe that she shared.

Every great company culture is based, in part, on intrinsic attraction and emotional commitment to important aspects of the company. People want to feel rewarded and recognized. They want to feel the pleasure of being part of a team. They want to learn. They want to work with others who are capable and committed. They want to be part of a culture that fosters all these qualities. When they find such a culture, they choose to be part of the enterprise. Work is no longer just transactional. They are reminded of the passion and curiosity that led them to their chosen field. They feel they can excel at their job, and they are ready to experience feelings of pride, belonging, adventure, achievement, and other personal benefits of accomplishment.