3. A Critical Few Behaviors

SCENE: Second week of May, late in the afternoon. A conference room in the Intrepid office, empty except for Katz and Alex. The detritus—empty coffee cups, flip charts full of writing— suggests that a larger group just vacated. One flip chart at the front of the room is labeled “TRAITS” and has just three terms on it: “Perfectionist,” “Consensus Driven,” and “Thrifty.”

ALEX: I thought they’d never leave! [Katz and Alex laugh.] But seriously, I’ve never extended the leadership team meeting from lunch until close of day before . . . people were pretty heated.

KATZ: The topic of culture can be a lively one, that’s for sure. Once you get people talking, it’s hard to know how to get them to stop.

ALEX: It was pretty quiet for the first fifteen minutes or so, when I introduced why we were here and talked about how I’ve decided that our business issues are related to culture and that we need to understand our culture better to move forward. I thought I’d lost them then.

KATZ: People are accustomed to leaders paying lip service to the topic of culture and launching a high-level “culture change” imperative—then moving on to the next thing. They’ve learned to tune out.

ALEX: [Ruminatively] Florence really saved me, though, when she brought up Calvin’s departure right away and framed it as a culture issue. What was it that she said?

KATZ: [Flips through his notebook] Here, I wrote it down. “If we don’t understand why our top people can’t see a future for themselves at Intrepid, then we’re not looking at our current culture and asking the right questions.” [Looks up at Alex] Yes, that was clearly a turning point. How did you view what happened next?

ALEX: It definitely brought the issues to life for some of the team. Like the head of operations, Ross—he usually doesn’t have any patience for the “fuzzy stuff” kinds of discussions. But he’d hired Calvin and he felt invested in his career, so Florence’s comment made it clear to him what’s at stake.

KATZ: Everything gets clearer when you surface the emotional subtext. All too often people in these discussions don’t recognize the importance of acknowledging the real emotions that lie at the heart of any conversation about an incident that leaves people confused or disen-chanted. The discussion helped Ross connect his emotional response to Calvin leaving—disappointment— with the larger issues of the business. That’s a great start. But what do you think is at stake? What do you think the leadership team walked out of here understanding?

ALEX: I think they understand that we can’t rest on our laurels—that we’ve been complacent for too long and that we need to modernize and move ahead or risk the end of Intrepid. That things like dragging our feet about customer analytics or procrastinating about taking cyber-security seriously—they aren’t just unrelated issues but part of a larger situation that really could endanger our long-term position.

KATZ: That’s well put. You’ve put your finger on what we call your “cultural priority.” That will anchor the discussions going forward, so it’s helpful. Does it feel like a different place than how you ended your last quarterly meeting?

ALEX: It absolutely does—it felt like there was a lot less fi nger-pointing. Avery is still cynical, but Avery will always be the cynic. However, even his habit of poking holes in arguments felt more constructive today.

KATZ: I agree. It’s clear that Travis and Florence did a good job engaging a lot of stakeholders, including most of these leaders, while they developed the list of traits. Most of the people in the room felt like they’d had a hand in the process, so they felt invested in the outcome. And I liked that you’d gotten feedback from middle management and even some frontline people as well. Are you happy with where the traits landed? Do any of them surprise you? Do they feel like they represent Intrepid?

ALEX: I completely agree with “thrifty.” [Smiles] The skeptics might even call us “cheap.” You nailed that one right away in our last conversation, so I was pleased how often it came up in the interviews over the past few weeks and in the room today. And “consensus driven”: that’s us to a tee. We can’t make a decision without talking to twenty other people, and we end up moving toward the least offensive rather than the boldest course of action. “Perfectionist” I found harder to get my head around. I’ve always thought people here were obsessed with processes and such rule followers. It’s interesting to me to see it as perfectionism, but of course that might be because it’s the trait I identify with the least. I don’t care if things are perfect—I just want them to get done! [They both laugh.]

KATZ: As much as you like to get things done, I don’t think it’s yet time to declare victory. It’s not enough to have a compelling “future state”—you need to motivate people to take real steps toward that aspiration. You’ve developed a real, collective, dare I say “consensus driven” [winks] point of view about Intrepid’s culture today. These traits underlie how you all operate. This is the first step in aligning culture behind strategy. And you have made a good start on the second step, which is understanding how these traits are making people feel.

You’ve also articulated more clearly where you’d like to get to—a more modern organization, one that can move quickly with bold ideas, better execution, and more practical ways of approaching costs. The next step is behaviors. You want to show how people can behave differently. This is where the rubber meets the road.

ALEX: You’ve said this to me before about behaviors, but I’m tempted to just let things play out for a while. Don’t you agree with me that today felt like a real step forward? Like a watershed—maybe now that the leadership team “gets it,” we’ll see some big changes around here.

KATZ: If you stopped now, you’d make a classic mistake. But don’t feel bad—it’s exactly the same error most leaders in your shoes make: declaring victory too soon. It’s not enough to get leaders to develop insight about the culture. Of course it’s great that the people in the room today—Ross, Travis, Florence, Avery, all the rest—have a deeper insight about what motivates people at Intrepid. But now you need to connect this understanding to new ways of acting, both for them and for other people. You need to get down to the level of behaviors so you can build more emotional energy and commitment around those behaviors.

ALEX: Give me an example. I’m a tactical guy. Tell me what that would look like.

KATZ: Well, the topic of the former green initiative came up a couple of times. Avery brought it up after the discussion about Calvin’s departure as another example of something that he believes is “broken” here at Intrepid. Did you catch that?

ALEX: Yes, that was interesting. I didn’t know that he and his marketing team had put so much work into Toby’s green campaign. He was clearly very disappointed that it hadn’t gone anywhere.

KATZ: Imagine if that initiative, instead of being a top-down one based on posters on the wall, had evolved from the trenches, from the real ways that people worked. Then you might have seen real commitment: emotional alignment, not just rational compliance.

ALEX: [Looking skeptical] Are you saying the green initiative could have transformed our culture? That sounds too easy—like we’re leaving aside the question we started with: how do we get the whole organization to be nimble, to move into the twenty-first century?

KATZ: That is not what I’m saying. Culture is a much broader issue than companies just doing good. If Intrepid’s culture were better aligned with its strategic and operational priorities, it would be easier for a leader to design something like a green initiative to be practical, “sticky,” and self-sustaining. And it would also be easier for leaders to design other initiatives, like a cybersecurity one, that had more than a snowflake’s chance in heck of making it off the ground—because they could ask, “How do we do this in a way that goes with the grain of how our people behave and what they feel good about doing, rather than working against it?”

ALEX: I see. That sounds like a great idea, but how does something like that happen? What’s the path?

KATZ: The path forward is not unlike the work you’ve been doing since we began a few months ago. Again, I’m asking you to look within your organization, to find what’s best and strongest and what generates positive emotional responses from your people. You ask people at all levels across the organization about how they do their work every day. You find behaviors that are already being performed today that represent the best of Intrepid. You ferret out the feelings that are generated by these behaviors. Then you have the discipline to select and connect the “critical few” behaviors with those feelings that will provide balanced motivation over time.

ALEX: Okay. You go wide, and then you go deep. And you keep these conversations moving toward an end goal. That is beginning to make sense to me, but it also sounds like a ton of work! How do I do all this and keep running the company as well? [He glances at his phone, as if the sheer weight of all the unanswered emails from the day is pulling his eyes toward the table.]

KATZ: I actually think it would be worthwhile to hand over key elements of this undertaking to a few of your leadership team members—the critical few who already seem to be on board—and to let them run with it. Florence and Travis feel obvious; Avery might be an unconventional choice, but sometimes a cynic can be useful. It’s worth talking to him one-on-one. But you don’t want this to be just a leadership effort. You want to engage people further down and make them part of the movement. You can also use this as a way of enabling collaboration among leaders who seldom have a chance to work together in their formal roles.

[Katz slows down as he finishes, noticing that he’s lost Alex’s attention to his phone. Alex looks up, apologetic, and holds up a finger as if to speak. Just at that moment there’s a knock on the conference room door, and Florence comes in, clearly excited.]

FLORENCE: I have some fantastic news—guess who just called and asked if he could have his job back? Calvin! The e-commerce company wasn’t a fit. He’d like to be back at Intrepid, if we’ll have him.

ALEX: I just saw that email and was about to tell Katz. If you’ll both excuse me, I’m going to step out and give him a call. [He leaves the room.]

KATZ: That’s amazing! I look forward to meeting him; Alex has said great things. You look concerned, though.

FLORENCE: I’ve hired a replacement for him—she started last month and is really digging in. I don’t know that I have room for him in my budget. [Alex reenters. He clearly seems keyed up and a little distracted, but he enters smoothly back into the conversation.]

KATZ: I have an unconventional suggestion, and I think Alex will be on board. [He looks at Alex, and they smile and nod at each other.] Bring Calvin on in a special projects role, and have him run the cultural alignment efforts for the next few months until you see where his next role will be. He’s clearly the kind of guy who speaks truth to power and has the respect of people on the leadership team. Maybe he could spearhead an initiative for evolving the culture.

FLORENCE: [Looking curious] So the cultural effort is a thing now? I’d like to be part of it also.

ALEX: I fully support that. Let’s figure it out. Florence, let’s set up some time tomorrow. We have real work to do. Katz, I’m not sure we’re done with you yet—please don’t go too far.

KATZ: I’ve got plans to see my granddaughter’s dance performance this weekend, but I’ve decided to stick around the rest of the week—I hear that lamb chops are the special at Casimir’s this evening, and I’d love to keep chatting. Why don’t we get together in a few hours?

CHANGE BEHAVIOR FIRST

Any leader who, like Alex, is struggling to understand how to harness emotional energy to drive priorities faces a basic challenge: How do you go from diagnosing to directing? Once you develop a clear, outside-in, nuanced perspective on the tendencies and inclinations within your organization today, how do you encourage that culture to evolve in a new direction? What are the ways to get more people to participate in the human interactions that will drive business results? How do you go from just talking about how things should happen to actually getting people in key places to take actions that yield better results?

We believe that there are specific ways to intervene in corporate cultures—to take tangible steps that not only accelerate near-term business results but also help support real, lasting culture evolution. It is important to recognize that lasting culture evolution is slow and steady at best. However, it is also important to note that successful, long-term organizational change efforts include simple, clear changes in specific behaviors. And the more these changes become habitual with respect to keystone habits, a term coined by writer Charles Duhigg (more on him in a minute), the better. Employees aren’t necessarily aware that they’re affected by a culture change effort. But they know that they are going to act in some new way at work, that the change is permanent, and that there’s a reason for it. A new practice, day by day, can become habitual, rewarding, and socially encouraged instead of labored, sporadic, and discouraging.

Our belief is supported by research in the fields of both management and neuroscience, as well as our own decades of hands-on client work. And it can all be boiled down to one of Katz’s most beloved quotes, attributed to Richard Pascale, coauthor of The Power of Positive Deviance: “People are much more likely to act their way into a new way of thinking than to think their way into a new way of acting.”

This is the key to the kind of behavior change that will enable an organization to evolve to a more coherent, strategy-supporting culture. To illustrate, let’s return to the Kate Dugan story from chapter 2. The partner on Kate’s project encouraged her to try something new by aligning the action—in this case, facilitating a senior meeting—to a trait she had an emotional connection to, “sleeves rolled up.” Why was this effective? He encouraged her to challenge herself by appealing to her natural human desire to feel connected with a larger group. He delineated for her the way that her individual act would align and connect her to an appealing group characteristic. He also drew a connection between that trait, which resonated with her own value set, and a larger strategic objective of the company: impact on clients.

For Kate, this experience was a positive one. How do we know? Years later, she still recounts this story. It was a moment that mattered to her, emotionally as well as rationally, in the course of her career. Kate has become an adept facilitator, and it’s a skill in which she takes great pride, in no small part because she once considered it out of her reach. She has repeated and internalized the behavior: it has entered her tool kit, as we say in consulting. It has become, through repetition, ingrained as well as habitual. This is a great example of behavior change and how it operates within the workplace, at the intersection of the individual’s personal lived experience and the person’s association with, and larger connection to, a greater whole. It also illustrates how change drives and is driven by basic emotions.

The idea that changing behaviors, rather than mind-sets, is the most practical way to intervene in an organization’s culture is at the heart of the critical few approach. Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, writes persuasively about the transformative power of keystone habits. For Duhigg, a keystone habit is “a pattern that has the power to start a chain reaction, changing other habits as it moves through an organization.” In other words, if you want to change the way people think, you don’t start with or rely primarily on rational argument. You change what they do, even if it doesn’t come naturally to them at first. Over time, as the new behavior becomes a pattern, they will likely change how they feel about doing it. They will see rewards or results of some kind, and those generate positive emotions; those emotions then become associated with the action, encouraging it to be repeated.

In a 2016 piece in the New York Times, “How Asking 5 Questions Allowed Me to Eat Dinner with My Kids,” Duhigg applies the keystone habits idea. Duhigg’s family faced a common problem: their chaotic daily lives made it difficult to sit down to eat together as a family. But instead of throwing up their hands, they approached the aspirational goal of frequent family dinners with the tools of management science. Duhigg applied the classic Toyota Production System technique of the Five Whys—framing the problem and then repeatedly asking “Why?” to uncover root causes. Through this process, the Duhigg family found a root cause of their family disorder: the family was often late getting out the door in the morning because it took so long for the kids to get dressed, triggering a cascade of delays throughout the day. The family developed and agreed on a solution: the children selected and laid out their school clothes the evening before. The net result of this action, the Duhiggs found, was calmer mornings, more productive workdays, and a higher frequency of evening dinners together at home.

Choosing outfits the night before is a perfect example of a keystone behavior, or what psychologists call a “precursor behavior.” It is actionable, specific, highly visible, and able to deliver short-term results. It is viral—but in this situation, it “infects” and encourages other positive behaviors that collectively helped the Duhiggs accomplish their stated goal. Significantly, it can be tracked and measured. You can imagine a homemade Duhigg family calendar with specific boxes that each child would check each time the clothes were laid out and a star at the end of the week celebrating the number of family dinners they had eaten together. If you can see and celebrate changes, they are far more likely to be repeated. We all, as humans, seek affirmation: we can take advantage of this human trait to encourage behaviors that we want to see repeated.

IMPACT OF CHANGING BEHAVIORS: EXAMPLES FROM OUR WORK

Clearly, an individual, or even a group, can use a behaviors-focused approach to make some desired change, but is it really possible to apply this principle across complex, global organizations? We believe that it is and that the discipline, persistence, and patience that Katz recommends to the fictional Alex is the key to expanding these types of incidents and stories into real, lasting, scalable change. And we believe that our work of the last few decades demonstrates this hypothesis.

A few years ago, James led work with a major oil company on a behaviors program designed to shift elements of its global culture to better align with its strategic objectives. One of these objectives involved an organization-wide need to operate at a slimmer margin. As a way of surfacing potential ideas to accomplish cost savings, platform managers were encouraged to conduct weekly meetings focused specifically on cost-saving ideas: this was much like Duhigg’s Five Whys exercise with his family but at a much larger scale.

In these conversations, managers pointed out the monumental operational expense of repairing or even replacing equipment that had been mishandled. As it turned out, many of the frontline people who used these machines on a daily basis simply weren’t aware of their costs. Up until this point, they had not connected their individual behavior (how they handled equipment) to their organization’s larger goal (managing costs for competitive advantage).

Once this connection had been clarified, the people themselves came up with ideas to better economize. At one site, a frontline employee proposed labeling all the machines with price tags. A discernible drop in repair costs was the immediate result. This early, noticeable impact spurred other observations and new behaviors—for example, one employee then pointed out that the general practice of running cooling fans at all times was superfluous when the temperatures dropped. Thus began a new practice of turning off fans when they weren’t necessary, leading to further cost savings. And these ideas then jumped from location to location. Idea by idea, more cost-conscious ways of behaving came into being, spreading organically across the organization. These habit patterns were recognized, acknowledged, and rewarded—and this positive bias led to their repetition. The behaviors moved from one-time acts to ingrained ways of getting things done. Thus, a new way of behaving became more prominent in the overall culture. What previously had been neglected became both a source of pride and the kernel of an idea that spread through peer networks.

In another client example from Katz’s work, a telecommunications company was seeking to improve customer service. Prior to our conversations with company leaders, this company had launched countless other efforts to achieve this goal and had seen little impact. Many organizations, we find, begin with the hope that a communications campaign can fit the bill, and this company was no different. But posters on the walls of the call centers urging employees to be polite to disgruntled customers had had little effect. A more intensive effort was made to ferret out the “root cause” by rolling out empathy training for all call center staff, but again, the program did not lead to any discernible difference.

Our work with this company began with intensive conversations with the call center employees themselves—about these failed efforts, yes, but more broadly about the potential value in their daily jobs, what motivated them, what frustrated them, and what helped them get through their most difficult days. It became clear to us that previous efforts had approached the problem as one of mind-set—leaders had made the assumption that employees could be mandated or trained to think differently about their customers, to approach interactions with more empathy, and that this empathy would lead to a rise in customer service quality. Leaders were not wrong in believing in the connection between empathy and customer service—indeed, our Katzenbach Center research has demonstrated that customer service companies that embrace an institution-wide ethos of empathy realize a sustainable competitive advantage—but their error was in believing that such a change in perspective could be mandated and controlled, rather than cultivated and encouraged.

We took a different tack. Through our observations of call centers and analysis of their data, we noted that the centers in which customer service scores were high had something notable in common: a markedly positive emotional connection among people on teams. To be more specific, teams that worked well together and enjoyed one another’s company also treated customers with more dignity and respect. Changed behavior, habitually sustained, equals changed mind-set—simple, compelling, and permanent. This observation helped us work with leaders to develop a new approach to supporting call centers in their customer service empathy: a training program based on teaming behaviors, which leaders had come to believe were the “root,” “keystone,” “precursor” behaviors to better customer outcomes.

FROM KEYSTONE TO ORGANIZATION-WIDE BEHAVIORS

What is required to apply this simple concept of keystone behaviors to the transformation of a complex global organization? Time, patience, and the willingness to be selective. To explain, let’s compare the Duhiggs’ dinner experiment with our oil company and telecommunications examples. Imagine the duration of the Duhigg family experiment: likely, it played out over a few weeks. To succeed, it required the collective commitment of four people—from the sounds of it, four busy people, but nevertheless just four. By the end of a few weeks, they were able to see and understand certain patterns and therefore could better determine (a) what was working and (b) how potentially significant this was to the larger effort to achieve their stated goal of more frequent family dinners. By contrast, the oil and telecommunications examples, although they follow the same simple logic and illustrate the same core principles, unfolded over many months against a backdrop of constant hypothesizing, idea collecting (and discarding), experimentation, and leadership alignment. Other ideas bubbled up and proved less effective (persuasive, actionable, repeatable, realistic) than the clever price tag and teamwork ideas that ended up in these stories. Discipline, selectivity, process, and collective commitment across large groups of leaders at all levels were required to get from a portfolio of new ideas to a few clever ones with the potential for real organization-wide impact, a trial-and-error tolerance to sift through and shake out the critical few. Exhibit 3.1 shows a framework that has been helpful in these types of conversations, making clear what is meant by behaviors.

Exhibit 3.1 Explaining behaviors

Many leaders find it hard to pick just a few behaviors to focus on. So they pile one directive on top of another. They overinvest in the pursuit of comprehensive frameworks. They then assume, “With all this effort, all these mandates, surely I’m going to see change now.” Their efforts to improve performance remain ill-focused and diffuse; even when efforts are aligned to the same ultimate goal, they can clash with or even undermine one another. In short, most efforts to address and change culture are too comprehensive, pro-grammatic, esoteric, and urgent.

That’s why narrowing to a critical few behaviors is essential. Once the behaviors are identified, clarified, and supported, they can strengthen the existing culture. The powerful difference between an alignment approach that focuses on a critical few and an approach that attempts to change a whole culture to align with an external framework lies in the simple act of being selective, the pure, true heart of pragmatism.

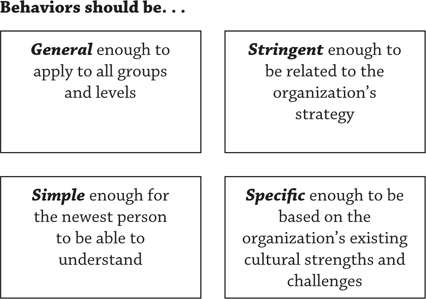

So selection is key. But before you can become selective, let’s be clear on what we mean when we say “organization-wide keystone behaviors.”

DEFINING ORGANIZATION-WIDE BEHAVIORS

Exhibit 3.2 is a brief excerpt from a list of effective organization-wide behaviors we’ve developed through repeating the process we’ve described with clients around the world. Note the primary characteristics they have in common: To begin, they are concise and coherent. They are also directive. Each begins with a verb, and this is deliberate. This syntax choice reflects the ultimate goal for any critical behavior: it can be acted on. It isn’t an emotion, an attitude, or a perception. Although those things are important, they cannot be seen, publicly addressed, or measured; therefore, we don’t allow them in this list. The behaviors are also simple. Although they reflect intimate conversations about each client and how employees work together, they can also be understood by the newest employee.

Have we compiled a comprehensive list of all the best behaviors? Have we ranked them to see which are most effective—which will give you the “performance culture,” the “aligned culture,” or the “innovation culture” you seek? If only we had a dollar for every time we heard those questions! We have disappointing news to share: There are no perfect behaviors. A behavior that is effective at one company may not be effective at another, and behaviors that are especially helpful in one industry may be irrelevant in another.

Organization-wide behaviors

• Use business goals and the mission to guide day-to-day project work and decisions

• Enable others to make decisions

• Foster explicit conversations about trade-offs between quality, speed, and budget

• Recognize each other for achievements, and back up and support each other

• Give your expert input freely and willingly, but if someone decides to go another way, support him or her

• Create a need for certainty, and do not allow decisions to be reopened

• Get to know others in social settings

• Use a data-driven approach to evaluate risks and be accountable for your recommended solutions

• Name decisions and the facts behind decisions clearly

• Spend more time outside the walls of the office getting to know customers

• Use rigorous internal networking to build cross-organization relationships and pursue mutually beneficial goals

• Look proactively for upstream and downstream implications before making system changes

• Align resources explicitly to prioritized opportunities to maximize impact

Exhibit 3.2 Examples of organization-wide behavior

The good news, however, is that certain behaviors are right for your company, right now, and if you understand your culture traits, you are likely to uncover them. Traits are neutral; desired behaviors are positive. You will be looking for behaviors that, when encouraged, will move your organization in the direction of your stated aspirations and your strategic intent, all while aligning to those fundamental traits of who you are as a company. This is, in a nutshell, working with rather than against the grain of your culture.

An effective behavior for your company should

• Harness existing sources of pride or emotional energy to drive intrinsic motivation toward your aspirations. Sources of pride differ across companies. For example, employees at a mission-based hospital network may be driven by a commitment to patient care. People working for a large, established company may take special pride in being associated with a premium, globally recognized brand that they can boast about to their neighbors. Individuals working at a startup may relish the challenge of creating new things. In the process of understanding your existing culture traits, you should have already gotten a good idea of these sources of emotional energy.

• Address barriers that get in the way of realizing your aspirations. For example, while defining your culture traits, you may have identified that consensus-based decision-making prevents you from moving quickly and being at the forefront of innovation. An effective behavior could thus be individuals taking accountability for decisions rather than seeking consensus.

• Encourage the replication of actions that enable your goals. If you made a long list of behaviors that are associated with each trait, you have already listed the ones that are most effective. Choose a few to accentuate and add to your long list.

Although not every behavior will accomplish all three of the goals listed above, each behavior should accomplish at least one.

The best way to identify the behaviors that work for your organization is to do this exercise in parallel with the process of agreeing on your culture traits. You will use many of the same sources of information: interviews and focus groups, existing assessments, existing employee engagement surveys, and your own observations. During your detective work, you can compile a comprehensive list of behaviors that you believe have the potential to help the company achieve its aspirations, and then you can commit, with discipline and rigor, to a critical few.

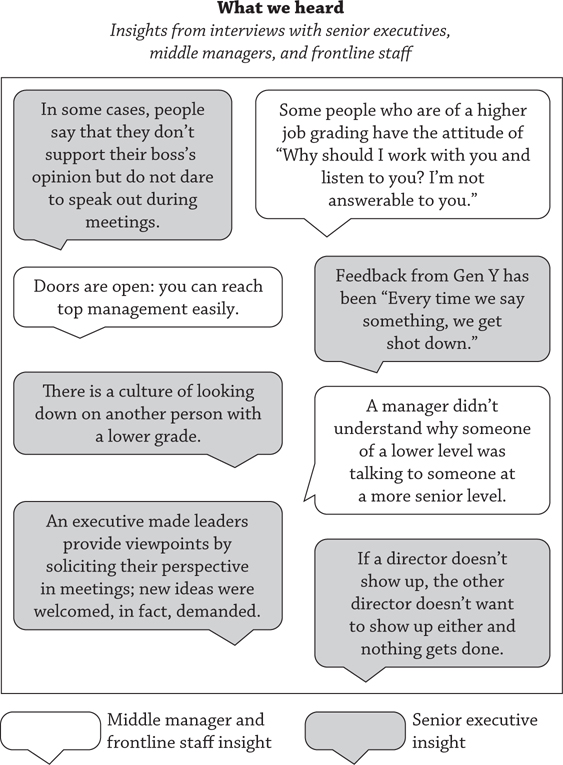

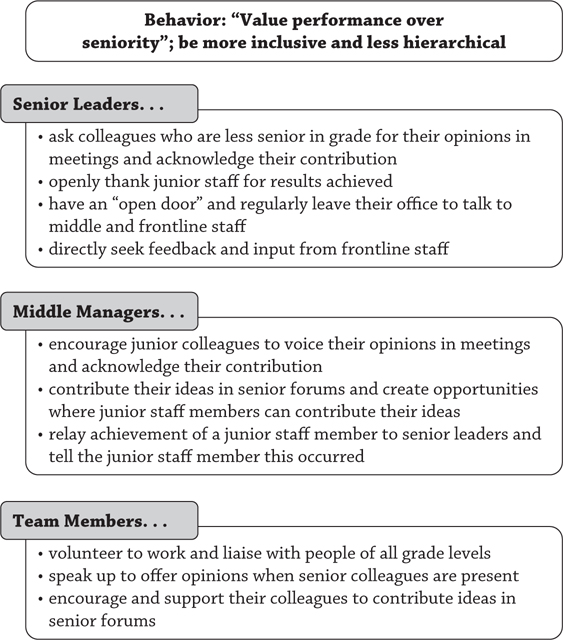

Let’s look at a real example to make this tangible. Exhibit 3.3 is excerpted from an analysis we conducted with a multinational organization that was employing the critical few approach to help accelerate a global transformation. Ultimately, through input from leaders at all levels, this company was able to arrive at traits as well as the critical few behaviors. An additional step in the process was the articulation of “aspirations”—in other words, the traits were “who we are today,” the aspirations were “who we want to be,” and the behaviors were “what we need to do to get there.” This company also found it useful to specify how the behaviors would manifest differently at different levels: senior leaders, middle managers, and the front line.

B. Aspirations |

C. Critical Behaviors |

|

Delivery focused |

Go the extra mile to deliver |

Front Line: Collaborate with colleagues and peers to solve customer problems Middle Managers: Prioritize process improvements that affect outcome Senior Leaders: Share feedback and celebrate examples where people have gone the extra mile |

Driving to formalization |

Stress teamwork; be more inclusive and less hierarchical |

Front Line: Offer to assist colleagues to get things done; ask questions to understand each other’s ideas; respond to requests for assistance promptly Middle Managers: Look for opportunities to help other parts of the business; always respond to requests for help and follow through; develop a sense of shared responsibility and goals across teams Senior Leaders: Always respond to requests for help and follow through; visibly support cross-functional projects and prioritize their needs |

Exhibit 3.3 From traits to behaviors

A chart like this reveals the kind of clarity that comes from rigorous analysis and tough conversations all across a company. The critical behaviors delineated here are not, at first blush, anything magical. Imagine if you walked into a gathering of the leadership team at a random company and said, “Instead of going through the effort to understand our culture, I’m going to save you some time. Let’s all, tomorrow, start behaving this way: ‘Share feedback and celebrate examples where people have gone the extra mile.’” At best, the leaders might say, “That sounds like a good idea,” try it once or twice, and then keep going about their daily routines. What are the chances that this behavior would lead to any outcomes? By way of contrast, consider how this actual client arrived at this list of the critical few. By the time this chart was created, the leadership team had dedicated hours of robust dialogue to conversations about the culture—what was working, what wasn’t working. They had addressed difficult issues that had bubbled up through focus groups and interviews with middle managers and frontline folks. They’d created a long list, and then they had narrowed it down— and significantly, in this narrowing, they’d all agreed (as far as it’s possible for leaders with divergent perspectives to agree) to focus on these specific behaviors—out of the full world of possible options. They had brainstormed measurable business outcomes that would result if these behaviors changed and discussed how to embed them in different areas of the business. They had looked one another in the eye and committed to hold one another accountable to upholding these behaviors, which included calling others out for failing to demonstrate them.

The point is, the magic lies not in the content of each specific behavior but in the process through which it came into being. The process, not the right and only possible answer, is what generates energy and emotional commitment.

BEHAVIOR DEVELOPMENT: THE LONG LIST

As previously discussed, a long list of behaviors will emerge through the process of understanding your company’s culture traits. As you conduct the discussions that will allow you to paint a picture of “the way things get done around here,” press for and collect behaviors. Make a note of them, and try to keep them positive; look for those that generate positive emotions and connectivity between people. This doesn’t mean, however, that every conversation about culture should be a rosy one in which any complaints or frustrations are immediately brushed under the rug. To get to the critical few behaviors, people will almost always go through a brainstorm step where they list their pain points and get specific about what isn’t working. Ask questions about what gets in the way of people’s best days of work or what keeps all of you, as a company, from achieving what you aspire to. (Ask, “What keeps us from being more innovative?” “What gets in the way of our processes’ working more smoothly?”) Move quickly beyond the negative, though. Lingering too long in the “complaining about the culture” stage will simply reinforce behaviors you’re trying to change by drawing attention to them and will associate the culture effort you’re undertaking with the idea that you can fix what’s broken.

Focus next on identifying the positive behaviors that can move your company forward. Look for what is already happening on its own. Remember our example of the telecommunications company—how customer service scores already were high in pockets in the organization? Find and probe these pockets. Consider the entire enterprise carefully. Somewhere in your organization, individuals or teams already manifest the types of behaviors that, if practiced more consistently more of the time, would help your organization accomplish its goals. Managers are empowering employees, encouraging them to see mistakes as learning opportunities. Team leaders are promoting and demonstrating collaboration. Leaders are embracing new ideas or championing forms of integrity—for example, refusing to bend the rules in a certain way or getting rid of outmoded rules and practices. Ask yourself, Why did people in these places behave differently from people elsewhere in the enterprise? Take stock of these positive behaviors and consider which could be harnessed to help others make desired changes.

How can you tell they’re the right behaviors? Because they fit closely with the traits that have already been identified. If you look at your long list, you should see how every behavior is relevant to your existing culture, either by strengthening something that is working or addressing something that is not supporting your strategic goals. In addition, these behaviors should make a difference in any significant geography where you operate and in multiple functions and levels.

BEHAVIOR SELECTION: THE CRITICAL FEW

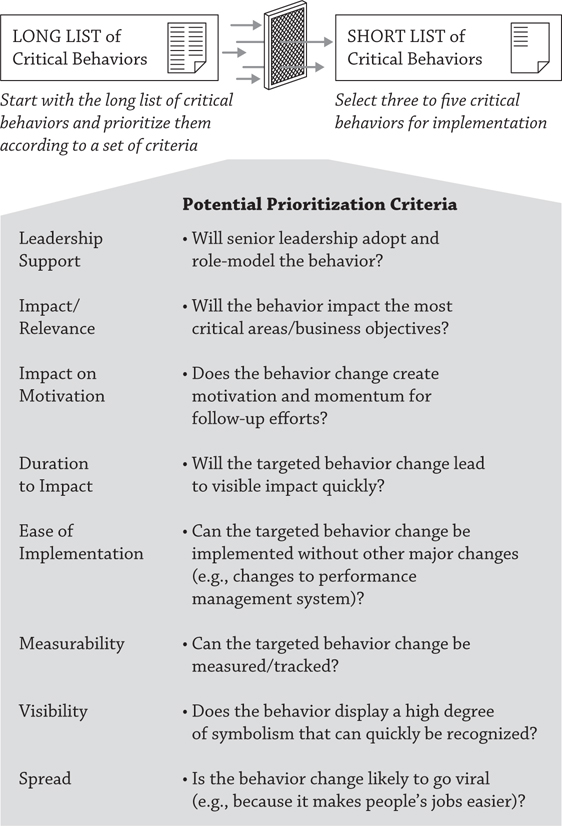

At this stage in the process, you’ve developed a long list— presumably, ten to fifteen behaviors that meet the criteria outlined above. Now comes the fun (and the extremely challenging) part: selecting from your long list to attain the critical few. Exhibit 3.4 is a high-level view of how the selection process works; specifics will follow.

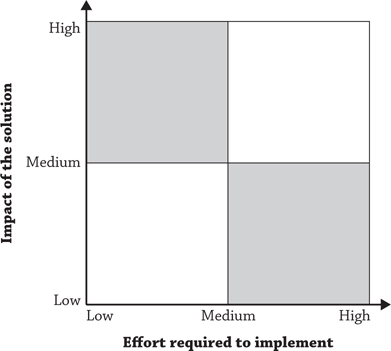

We’ve seen different approaches be effective here. One common way is to plot the behaviors using the axes of effort to implement and impact, as shown in exhibit 3.5.

This is a simple two by two framework that encourages a conversation about trade-offs and requires realism about what can be accomplished. Other organizations use a voting process, which can vary from the public and very low tech, like a simple show of hands, to the private and electronic, like a voting tool.

Working with clients around the globe, we’ve observed that there is no perfect way to get from the many to the few. Indeed, the process that clients choose usually reflects (and teaches us about) how information is processed and decisions are made within that particular culture. For example, in our work with a financial services firm in Asia, we quickly realized that the leaders had a strong preference for visual representations of the behaviors that emphasized how much data and analysis had gone into their development. This made the decision feel less impulsive to them, more data driven and precise. Therefore, for the leadership meeting where the critical few behaviors were selected, we papered the walls with large posters similar to what you see in exhibit 3.6.

The posters contained highlights of what we’d heard in interviews and focus groups, which clarified why each behavior would benefit the organization as a whole. They also suggested more specific behaviors that could apply at every level. Leaders spent their time together walking around the room, considering and discussing each behavior. This helped them feel, when they made the ultimate choice of just three behaviors, that they’d made a decision fully supported by data. By contrast, an entertainment company in a turnaround situation dedicated a few hours of its leadership team meeting to vociferous open debate and then quickly came to a consensus with a show of hands—consistent with the “get it done right away” trait that we’d noticed in the company’s culture.

Why the emphasis on just “a few”? And how will you know that you’ve chosen the right behaviors? The first question is easy to answer: because you need somewhere to begin. Changing everything at once is impossible. Focusing on just a few behaviors allows for consistency and coherence. You are, in essence, about to undertake a science experiment with your company, and just as with a science experiment, you need to establish a framework that will allow you to see and document results.

The second question is also easy to answer, but you might not want to share this information with the full leadership team before you try getting them to have a real discussion about choices: there are no perfect few behaviors. Likely, if you have been thorough and thoughtful in developing the long list, any of the behaviors would be useful and effective in moving your culture forward. The process deciding which ones to prioritize is, in and of itself, a form of intervention. By deciding on and committing to these behaviors together, you and your colleagues are taking a big step toward making your culture stronger and more coherent.

WALKING THE TALK: SYMBOLIC ACTS

In conversations with leadership teams about behaviors, one of the most powerful moments usually occurs when one leader turns to another and says, “What will you do differently, starting today?” The best leaders demonstrate the selected behaviors every day and at every opportunity. When the company leadership steps up and walks the talk, people take notice and then take action. All of an organization’s members should be expected to embed behaviors into their daily work, but those seen as leaders have both an opportunity and an imperative to do so in a way that catches people’s attention and sends a strong message that things are changing around the workplace.

A symbolic act is a deliberate, purposeful action taken by the leadership that sends a strong archetypal message. Symbolic acts can be undertaken by an individual leader or by a leadership team as a collective. What’s important is that they are explicitly designed and executed in a way that sends a message coherent with the overall culture evolution. For example, a collective symbolic act at a global airline client was the leadership decision to break the tradition of holding all leadership team meetings at the headquarters in Australia and to instead rotate the location every quarter across each of the continents the airline served. Significantly, this was not done quietly behind the scenes. This change in practice was announced by the CEO to the full organization, with an explicit connection made between this choice and the new behavior: “incorporate a global perspective in all major decisions.” At each quarterly meeting, local representatives were invited to attend and to provide a local perspective. It was a simple act with far-reaching implications.

In another example from our client work, the CEO of an investing firm made a bold and uncomfortable decision: he shared the full results of his 360-degree feedback with the rest of his team, warts and all. This was a way of demonstrating, visibly, that the goals the team had discussed of transparency and emotional commitment could be accomplished only when each person decided to take a step beyond his or her comfort zone. Other members of the leadership team emulated his action, sharing their own feedback. This is an example of an act going viral—with, again, very long-term implications for shifting the culture of this firm toward more trust and collaboration.

Another firm’s CEO chose to interpret one of his organization’s critical behaviors, “respect each other,” by drawing up a list of behaviors that he promised to practice with regularity: avoid personal remarks, never interrupt, and pay close attention to what everyone said. He also, in a move that reflected the same purposeful humility as the investing firm CEO’s gesture of sharing his 360-degree feedback, asked a few informal leaders on his team to call his attention privately to any of his notable hits and misses. This move likely caused him some discomfort, especially at first, but it had a powerful effect on his organization’s culture.

One of Katz’s all-time favorite examples of a symbolic act comes from the military. Alfred M. Gray is a United States Marine Corps general who served as an important leader throughout the turbulent, post-Vietnam 1970s and served as twenty-ninth commandant from 1987 to 1991. Gray is known for effecting a transformation sometimes called “the second enlightenment of the Marine Corps”; changes that are attributed to Gray include the emphasis on Marine Corps service as a leadership development opportunity and the establishment of a Marine Corps University. Formal photographs of Gray feature him in battle fatigues, not a dress uniform. Those outside the military might not understand how bold a message this sent: it emphasized the core ethics that Gray sought to build in the corps, including mutual respect and what he called the “warrior spirit.” And this was not simply a formal posture for photographs. Gray wore these fatigues at all times and entered mess halls without any insignia to eat the same meals as his Marine Corps privates.

In one CEO’s early days at the helm of a prominent technology company, the chief was lauded in the press for tearing down the fence around executive parking and taking an annual salary of $1. These were symbolic acts, to be sure—notable, as with Gray, for demonstrating humility. In our days working with the company under this CEO’s leadership, we also heard of a notable symbolic act that was powerful in how it demonstrated not just the chief’s own humility but the desire to redirect others toward new, more effective ways of behaving. Whether walking the halls meeting employees or hunkered down with the leadership team, the CEO regularly posed a question: “What are your competitors doing?” This would send employees scrambling to look outside the company’s walls and better understand the market—a behavior that the chief executive wisely understood as key to making a behemoth organization more nimble and outward facing. Core to this symbolic act was its element of repetition; because the CEO did it not once but repeatedly over time, a shift in behaviors was encouraged. Undoubtedly, people who had this experience told others about it and caused those others to work to understand competitors as well. Who, after all, would want to run into the CEO and not have a good answer to that one pointed question?

As different as these examples are, they all had a notable impact on the people in the organizations in which the leaders served—they catalyzed and deepened emotional commitment to both the organization overall and to the leader as an individual. This kind of emotional commitment, over time, helps each person take similar chances, to act and behave in new ways that might feel unnatural at first but ultimately become rewarding and self-reinforcing. When people can feel an emotional as well as rational alignment between their company’s identity and purpose and their own individual behaviors, they feel connected; when that sense of connection is attached to the organization’s ability to reach its goals, the organization has a culture that is working for and supporting its purpose.