22. Case Study: House Wing Addition

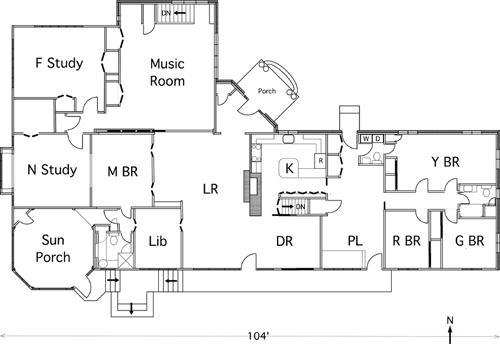

Plan of house after 1991–1992 wing addition

In fact, architecture can almost be taken as a prototype for the process of design in a semantically rich task domain.

HERBERT SIMON [1981],

THE SCIENCES OF THE ARTIFICIAL

Highlights and Peculiarities

Why This Case?

For this design, we have some 235 pages of the contemporaneous log of design issues, pros and cons, and decisions made over 13 years. From this log we undertook a formal decision-tree documentation, as detailed in Chapter 16. This case illustrates the interplay of design and the discovery of requirements treated in Chapter 3.

Bold Decision

Defer budget constraints; design for function; then value-engineer. This decision was made halfway through the design process when nothing was working.

Bold Decision

Move the Master Bedroom to the midst of the public and semipublic spaces. This decision was made late in the design process when a low-frequency use case revealed a hitherto unperceived requirement. This decision seemed at the time to mean essentially abandoning the east end of the house. As the family has subsequently grown, having that “hotel” end has been quite useful.

Key Decision

Buy a 5′ strip of land from the neighbor to solve an intractable design problem. The story is told in Chapter 3.

Phasing

Undertake the total house remodeling in two phases, to simplify our design and supervision task, as detailed in this chapter and the next one.

Plenty of Design Time

Design until we were satisfied, unconstrained by any construction schedule goal. In the event, the final design happened over some 60 months (with substantial interruptions), whereas construction took only 9.

Introduction and Context

Location:

413 Granville Road, Chapel Hill, NC

The house faces precisely north, so descriptions will be given in N, S, E, W terms.

Frederick and Nancy Brooks

Designers:

Frederick and Nancy Brooks

Advised at times by Wesley McClure, FAIA, and Alex Jones, ASID

Construction drawings by another draftsman

Builder:

Additions Plus (Stanley Stutts, contractor; Gary Mason, project master carpenter)

Dates:

Design, 1987–1992

Construction, 1991–1992

Supplementary Web Site:

During the design process, Fred and Nancy kept a detailed log of design issues, problems, thoughts, consultations with friends and professionals, and decisions, some 235 pages. Sharif Razzaque encoded the more significant parts of this as a Compendium graph, showing the decision tree, but not the detailed rationales for each decision. This tree may be consulted on the book’s Web site, www.cs.unc.edu/brooks/DesignofDesign.

Context

1964–1965

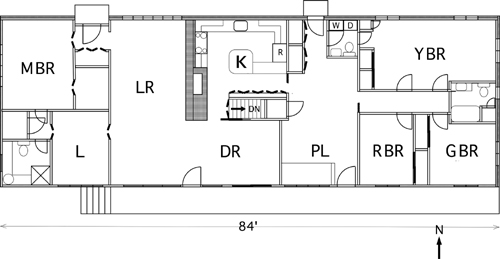

The original house (Figure 22-1), built in 1960, was acquired in 1964, chosen largely because of the large wooded, creek-bordered lot and convenient location, and in spite of obvious house shortcomings. The most serious single design flaw was the traffic pattern, especially the bottleneck between the Dining Room and the Kitchen, through which all east-west traffic flowed. Moreover, each room in the house was experienced as somewhat too small for its function.

Figure 22-1 Main floor as of 1987

When in 1965 we moved in, we had two sons, aged 7 and 3, and a 6-month-old daughter. To be near the children, we used the Red Bedroom as the Master Bedroom, and the other three east-end bedrooms for the children. The original Master Bedroom, at the west end, was used as a guest suite from 1965 to 1986.

1972

We finished the basement as an apartment and relocated our older son there; the second son joined him later. This enabled us to remove the partition and closets between the two northeast bedrooms, creating one large bedroom, the Yellow Bedroom, for our daughter. The Green Bedroom became Nancy’s Study.

1987

Our daughter graduated from college in 1986 and became an Army officer. Our sons were in graduate school or professional practice; one was married, with no children. With our children gone, we had more time for other activities, hence felt a need for more of certain spaces. Nancy Brooks had been teaching violin in the home since the mid-1960s; now she was able to teach more pupils.

Nancy’s widowed father, Dr. Joseph Greenwood, had just come to live with us permanently, living in the Master Bedroom (Guest) suite at the west end. Nancy had inherited her parents’ grand piano. This supplemented the one we owned, enabling two-piano music.

In various ways, the house was ready for a 30-year update. Fred’s Study was in the (ground-level-access) basement apartment, in what had been the sons’ quarters. Given our ages, it seemed wise to enable normal indoor living using only the main floor, should that become necessary.

Off and on over previous years we had tried to see how a 500 ft2 addition might be used to make the house more spacious, ideally by shuffling functions so that each room’s function got upgraded in space. These design efforts had been unsuccessful.

So now we began in dead earnest to design an addition.

Objectives

Original Objectives

• Improve the traffic pattern.

• Make more space in almost every room.

• Build a Music Room (MR) large enough to hold two grand pianos, a small organ, and a string octet with a 1′ teaching margin around the outside of the octet. The room must also hold music files. This size would get the two grand pianos out of the Living Room, where they were filling the north end and made a narrows for entry from the front door. The Music Room should also accommodate small student recitals with an audience of parents. Ideally, it would have a separate entrance.

• Bring Nancy’s Study (NS) from the southeast corner Green Bedroom to make it convenient to the Music Room and to Fred’s Study. Enlarge it.

• Get Fred’s Study (FS) upstairs to the main floor.

• Provide more function spaces: rooms and/or alcoves.

• Add a front porch (FP) large enough for a porch swing and other seating.

• Provide a screened back porch (this became the Sun Porch, SP).

• Modernize and enlarge the Kitchen (K).

• Enlarge the Dining Room (DR).

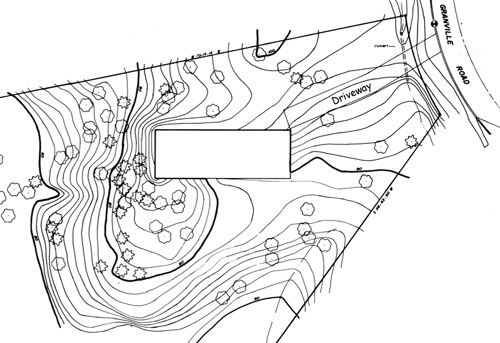

• Make the main entrance obvious as one approaches from the driveway (Figure 22-2).

Figure 22-2 North part of house site

• Improve the esthetics of design, especially outside, perhaps with a more interesting roofline.

• Enhance, or at least don’t hurt, the yard and site.

• Preserve trees to the southwest and southeast, flowers to the north.

• Capitalize on the view of the yard and gardens from within the house, especially from the public rooms.

Discovered Objectives

• Better accommodate the biweekly meetings of a student group we advise, about 40 people.

• Accommodate some 40 coats for attendees at recitals and student meetings.

• Provide storage for family goods currently in rental storage.

Constraints

Existing Structure

The plan, placement, and orientation of the existing structure determined the scope of the remodeling.

Site

The north property line and 15′ setback, and the 17′ shadow-casting requirements, constrained expansion.

Tree

A large black oak in the upper backyard was a main feature of the lot that we wished to keep.

Lot

The topography falls off fairly steeply to the west, starting at the end of the existing house.

Budget

Our target was $100K, and the expected cost of the addition was $100/ft2.

Non-Constraints

Budget

Our target of $100K was not an absolute constraint, as the purchase mortgage had been fully paid.

Resale Value

There was no need to consider whether investment in the addition would increase the resale value. From life expectancies and our plans not to move, we could expect some 30 years to amortize the addition before selling the house, by which time it would be ready for another update anyway.

Acreage

There was plenty of land; the lot has more than 1½ acres.

Time and Effort

We had plenty of design time and willingness to invest lots of design effort.

Events

Several events changed the design as it proceeded:

• Dr. Greenwood died in late 1988.

• The architect’s draftsman hired to make construction drawings misaligned the foundations drawing with respect to the main-floor drawing. This discrepancy was discovered after the foundation was poured. The fix was to enlarge the main floor by 1′ to the west and 1′ to the north. The chapter frontispiece shows as-built, rather than as-designed.

Design Decisions and Iterations

Explorations

Flip the House End for End

Redo the interior radically, making the existing bedroom wing into the public rooms—Music Room, Living Room, perhaps Nancy’s Study—and fitting the master and guest bedrooms into the old Music Room. Plusses: There would be easy main and student entrances, and we could perhaps add studies as an extension to the southeast. Minuses: This would be a costly change; we would need more bathrooms at the west end; we would waste the fireplace; and we would separate the Living Room from the Dining Room with all traffic coming through the Kitchen. We abandoned this option quickly.

Southeast Wing

Build a new Master Bedroom suite out from the southeast of the house, perhaps incorporating the Green Bedroom. We abandoned this idea to preserve the white oak and red oak trees at the southeast of the house, and the access from the driveway to the apartment and the backyard.

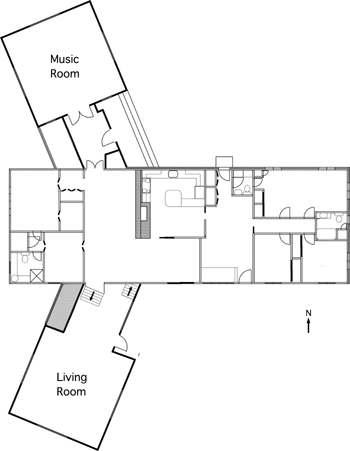

McClure’s pavilions (Figure 22-3)

Plusses: The Music Room (North Pavilion) becomes almost entirely separate, with easy access from the driveway and good acoustic isolation from the house. The Living Room (South Pavilion) has superb views into the garden and yard. The freed-up Living Room converts to an inglenook around the fireplace for reading and conversation. Minuses: The South Pavilion would require sacrifice of the magnificent four-trunk black oak. We would not be able to use the living space to enhance the Music Room for recitals.

The South Pavilion was abandoned rather soon, so with it went the redesign of the Living Room to include the attractive inglenook.

Figure 22-3 McClure’s pavilion sketch

The North Pavilion stayed in the main line of design, undergoing many shape and configuration explorations and ultimately becoming the north wing, incorporating the Music Room, Fred’s Study, Foyer, and Front Porch.

Partitioning the Design Problem

As we proceeded, it became clear that we could partition the house redesign into three almost separate problems:

• Old East: the bedroom end, perhaps including the Playroom

• Center: the Kitchen, the North Hall and its closets, Playroom, Laundry/Toilet, basement stairs

• Old West: the Music Room, Dining Room, and West Bedroom suite, together with the new addition, New West

This partitioning proved liberating; all later design used it.

Phases

Fairly early, we decided to have two design and build phases, several years apart, chiefly to give manageability to the design and supervision tasks. Phase I would be the Old West–New West part; Phase II, the Kitchen and Playroom part. Phase II is treated as a separate case study in Chapter 23.

East End

Various East End redesigns were done, all aimed at giving the Master Bedroom its own shower-toilet and providing a comfortable suite for Dr. Greenwood. Some rather tentative explorations looked at moving the basement stairs to the Red Bedroom or sharing between it and the Playroom. After Dr. Greenwood’s death, the requirement for a bedroom/bath suite in addition to the Master Bedroom vanished. As a result, after we moved the Master Bedroom to the West End late in the design process, we abandoned the East End redesign effort and left it as it was.

It serves as the Guest Suite, unheated and uncooled except when there are visitors. Roger’s family now has five children; Barbara’s has four. A visit from either fills this suite and the basement apartment.

Function Placement within West Half

The most extensive exploration concerned placement of functions in both Old West and New West, which were considered as one allocable space, although existing room walls were implicitly honored in most deliberations.

These explorations occurred before the decision to keep the Master Bedroom in the West End; the old Master Bedroom was assumed to be part of the allocable space. So all the early deliberations concerned only where to put the Music Room, the Living Room, the Dining Room, Library, Nancy’s Study, and Fred’s Study. The plan in the chapter frontispiece is misleading at this stage.

Having ruled out extension to the south, we considered additions to the north, to the west, and in both directions. Function allocations considered were

• Music Room west and Living Room north

• Music Room north and Living Room west

Change of Approach: Forget the Budget as a Design Constraint

As these explorations proceeded, it became evident that the budgetary constraint, translated into 1,000 ft2, was inhibiting our thinking. So we decided to design to meet the objectives, then later cost-engineer and/or decide to spend more money if it then seemed worth it. This radically freed up our thinking.

I have for some years advocated this approach to the design of computer graphics systems. In that domain, I had discovered that the best way to make a cost-effective application system is to make an effective one, then cost-reduce it, rather than making a cheap one and augmenting it until it is useful. It took me too long to come to this same approach on the house.

Newly Discovered Requirement: Where to Put the Coats?

In November 1990, we were checking a tentative design by running various (extemporaneous and undocumented) use cases against it. We did this in more detail than we had earlier, because the design was more congealed. We ran the biweekly scenario of a dinner meeting of the 30- to 40-person student group for which we are faculty advisers and hosts.

As the guests enter in winter, they place their coats somewhere. Where? The Foyer coat closet clearly wouldn’t hold them. On the music instruments? All over our Studies? Where do they put them now? On the bed in the Guest Room, adjacent to the Living Room. Oh—that room is gone in this design.

One solution would be to enlarge the coat closet, quite substantially. Another would be to keep the Guest Room in the West End, move into it as the Master Bedroom, and quit redesigning the East End. The gross cost: making the westward extension larger, by at least the present width of the Guest Room. The net cost: gross cost less the East End costs not undertaken.

Problem

If there is a westward extension beyond the Master Bedroom, it must be integrated with it to meet code requirements for sleeping spaces; there can’t be a closable door between the bedroom and windows.

Corollary 1

If we put Nancy’s Study as the westward extension, that integration is not problematic. No other room could go there. (Fred often studies while Nancy sleeps, but not vice versa, so his study can’t go there.)

Corollary 2

If the Music Room isn’t to be in the west extension, it should be in the north one. This keeps it isolated from the main living quarters and makes it convenient for access from the driveway.

Convergence of Function Placement

Things then rather rapidly fell into place.

Living Room

In order to meet the recital requirement, it would be desirable to integrate the Living Room and the Music Room sometimes, but not most of the time. This was solved by a 12′ sliding door (four panels), moving into a new pocket on the outside of the north wall of the Master Bedroom.

The Living Room enlargement was accomplished by absorbing the original Foyer, the original Foyer coat closet, and the original Guest Room closet—all to be replaced in the new wing. Of course, moving the two grand pianos out to the Music Room made an immense difference in the Living Room’s effective size.

Fred’s Study

The logical place for this now became a filling-in of the corner between the north wing and the west one. This was done with space for a new Master Bedroom closet off Nancy’s Study and other closets. The North Hall also accommodates the copier, centrally adjacent to the Music Room, Nancy’s Study, and Fred’s Study.

Sun Porch

The desired south porch nicely fits into the southwest corner of the New West wing. Originally we envisioned it as a ground-level porch. When we saw how the necessary steps down from the main floor would eat into its space, we kept it on the main-floor level. Likewise, use-case checking led us to glass it in, with many operable windows, rather than screening it. An outdoor porch would be underutilized—too cold in winter; too hot in summer.

Front Porch

The Front Porch went through several iterations; originally it covered the whole east face of the north wing. In the event, we kept the original diagonal orientation of McClure’s North Pavilion, facing out directly toward the approach to the house from the driveway. It was made big enough to accommodate two facing porch swings, which has created an unexpectedly useful conversation site.

The porch gable created by the 45° orientation solved two problems. First, it provides an obvious entrance for the house. Second, it neatly smooths over the joint between the old house’s 8′ ceilings and the new wing’s 9′ ceilings and their corresponding eave lines (Figure 22-4).

Figure 22-4 View of the remodeled house from a northeast approach

Basement Storage

A late-discovered opportunity was the possibility of putting cheap storage space under the west wing, because the terrain falls off so rapidly. Modest excavation and low-cost finishing yielded a 530 ft2 closed-in storage area under the Music Room, a small workshop, and space for the new wing’s mechanicals. This enabled us to give up remote storage we had been renting, with more convenient access.

The Property-Line Setback Constraint

Chapter 3 tells the story of the most interesting single design problem and decision. The Music Room objectives were quite specific and constrained it to be rather squarish. This and any reasonable configuration of Fred’s Study conflicted with the 17′ shadow-casting setback requirement of the Town of Chapel Hill. Extensive design iterations couldn’t solve the problem. We finally bought a 5′ strip of land from our neighbor.

Dining Room

A simple extension of the Dining Room to the south was designed. This would put the long side of the room north-south instead of east-west. It required a roof gable, as well as some awkwardness in the deck along the south side of the house. After cost estimation, we gave it up, purely as part of our cost engineering.

Changes during Construction

Fred’s Study Windows

As designed, the west windows in Fred’s Study were 4′ tall, starting 3′ from the floor. During framing it became evident that the westward-falling terrain meant that the view from those windows would be just treetops. So the windows were changed to 6′ tall, starting 1′ from the floor. This did indeed improve the view and the feel of the room.

This is the sort of problem that plans and elevations would never reveal, but that a virtual-environment simulation would have shown during design.

Organ Niche Window

Son Ken Brooks suggested putting a narrow window behind the bench of the new organ. This provides light to the Music Room from a third side.1

Assessment—Successes and Unresolved Drawbacks

Some 17 years have elapsed since the completion of the Phase I project, 14 years since Phase II, the Kitchen-Playroom redesign.

We have no “Wish we had done that differently” list. The unusually long design effort, with close attention to detail, paid off in livability, function, and delight. Of course, not all ideals are achievable, given the constraints.

Kitchen–Living Room Door

Cutting the door from the Kitchen into the Living Room had the most dramatic effect. This radically eased the traffic pattern of the house and gave end-to-end visibility.

Master Bedroom

The plan is indeed somewhat weird in having the Master Bedroom surrounded by other functions. The design depends upon resale value not being a consideration. Few families would need the big Music Room, Fred’s Study, and Nancy’s Study.

Music Room

This space works well for lessons and individual practice, because it can be closed off. It accommodates a big organ very well. It works for recitals and an annual workshop because of the wide opening into the Living Room. But it has no separate access. Students put shoes and instruments in the Playroom, then trek through the Kitchen and Living Room.

Living Room

Getting the pianos out makes it a new room. The enlargement via closet incorporation is welcome. But the greater breadth would have worked better with a higher ceiling.

Photo and video projection is awkward. There is no good place to put the screen.

Dining Room

This room is still cramped. The table can be extended into the Living Room, and auxiliary tables set up there, so the house can feed a lot of seated people.

Front Porch

The two facing swings make a separate conversation nook that is often used. The main entrance is now evident; the appearance, much improved.

New Functions

The redesigned house turned out to meet needs that we didn’t know we had. As noted in previous chapters, this is usually, not exceptionally, the case for products.

Sun Porch as Meeting Venue

The Sun Porch has turned out to be a very suitable room for meetings of up to a dozen people. A new Christian school was founded there and held its board meetings there for some years.

Music Room as a Living Room Extension for Meetings

An initial requirement was that the Living Room serve as a Music Room extension for musical recitals. It works well for that. Students and their parents, about 25 people, sit in rows of chairs that start in the Music Room and extend back into the Living Room.

The converse has unexpectedly turned out to be true. Meetings of the graduate InterVarsity Christian Fellowship normally run 30 to 40 people but have occasionally attracted over 50. These meetings focus on speakers by the Living Room fireplace, and the Music Room accommodates seating for the outer rows.

Deck, Steps, and Yard as Meeting, Eating Area

The deck along the south exterior wall was brought down to the upper backyard with broad steps and equipped with a fold-down table. This has proved to be a good outdoor eating and meeting space for the IVCF chapter. The steps provide a lot of seating.

General Lessons Learned

1. Spend time on design. We spent much more time per square foot than might have been cost-effective if the designer time were part of product price. The same thing is doubtless true of much of Linux. On Operating System/360, we would have benefited greatly from more design time before implementation got under way. I do not think the product would have cost more in total.

2. Talk many times, lengthily, with the principal user(s), showing prototypes they can understand.

4. Double-check the work of professionals, such as architects, draftsmen, and decorators. Make sure you understand it, and that it’s accurate.

Notes and References

1. Alexander [1977], A Pattern Language, advocates ensuring that each room is daylighted from at least two sides, preferably more. We followed this scrupulously, putting a skylight in Nancy’s Study and Fred’s Study (but carefully not in the Master Bedroom), and a window in the interior wall between Nancy’s Study and the Sun Porch. Thus, each of the new rooms has some daylight from three sides.