II

INDEX

“Diz ’n’ me gonna win 50 games.”

“We will land a man on the moon and return him safely in this decade.”

“I shall return.”

Each of these major plans met one great test: clarity. If your plan is clear, it will be easier for you to stay on plan. The other test of a good plan is that it works. It works for you because it's doable. It works in the market because it's realistic. It works because it helps you achieve your objectives.

Great coaches all agree with a simple summary of how to succeed in athletics: Plan your play and play your plan. That's why you'll want to develop a clear and simple financial plan and stay the course.

Here, we present a remarkably simple plan for investing that uses low-cost index funds as your primary investment vehicles. Index funds simply buy and hold the stocks (or bonds) in all or part of the market. By buying a share in a “total market” index fund, you acquire an ownership share in all the major businesses in the economy. Index funds eliminate the anxiety and expense of trying to predict which individual stocks, bonds, or mutual funds will beat the market.

This simple investment strategy—indexing—has outperformed all but a handful of the thousands of equity and bond funds that are sold to the public.

This simple investment strategy—indexing—has outperformed all but a handful of the thousands of equity and bond funds that are sold to the public. But you wouldn't know this when Wall Street throws everything but the kitchen sink at you to convince you otherwise. This is the plan we use ourselves for our retirement funds, and this is the plan we urge you to follow, too.

NOBODY KNOWS MORE THAN THE MARKET

It is difficult for most investors to believe that the stock market is actually smarter or better informed than they are. Most financial professionals still do not accept the premise—perhaps because they earn lucrative fees and believe they can pick and choose the best stocks and beat the market. (As the author Upton Sinclair observed a century ago, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”) The cold truth is that our financial markets, while prone to occasional excesses of either optimism or pessimism, are actually smarter than almost all individuals. Almost no investor consistently outperforms the market either by predicting its movements or by selecting particular stocks.

Why is it that you can't hear some favorable piece of news on the radio or TV or read it on the Internet and use that information to make a favorable trade? Because an army of profit-seeking, full-time professionals will have likely already pounced on the news to drive the stock price up before you have a chance to act. That's why the most important pieces of news (such as takeover offers) are announced when the market is closed. By the time trading opens the next day, prices already reflect the offer. You can be sure that whatever news you hear has already been reflected in stock prices. Something that everyone knows is not worth knowing. Jason Zweig, the personal finance columnist for the Wall Street Journal, describes the situation as follows:

I'm often accused of “disempowering” people because I refuse to give any credence to anyone's hope of beating the market. The knowledge that I don't need to know anything is an incredibly profound form of knowledge. Personally, I think it's the ultimate form of empowerment. … If you can plug your ears to every attempt (by anyone) to predict what the markets will do, you will outperform nearly every other investor alive over the long run. Only the mantra of “I don't know, and I don't care” will get you there.*

This doesn't mean that the overall market is always correctly priced. Stock markets often make major mistakes, and market prices tend to be far more volatile than the underlying conditions warrant. Internet and technology stocks got bid up to outlandish prices in early 2000, and some tech stocks subsequently declined by 90 percent or more. Housing prices advanced to bubble levels during the early 2000s. When the bubble popped in 2008 and 2009, it not only brought house prices down, it also destroyed the stocks of banks and other financial institutions around the world.

Nobody knows more than the market.

But don't for a minute think that professional financial advice would have saved you from the financial tsunami. Professionally managed funds also loaded up with Internet and bank stocks—even at the height of their respective bubbles—because that's where the action was and managers wanted to “participate” (and not get left out). And professionally managed funds tend to have their lowest cash positions at market tops and highest cash positions at market bottoms. Only after the fact do we all have 20–20 vision that the past mispricing was “obvious.” As the legendary investor Bernard Baruch once noted, “Only liars manage always to be out of the market during bad times and in during good times.”

Rex Sinquefield of Dimensional Fund Advisors puts it in a particularly brutal way: “There are three classes of people who do not believe that markets work: the Cubans, the North Koreans, and active managers.”

THE INDEX FUND SOLUTION

We have believed for many years that investors will be much better off bowing to the wisdom of the market and investing in low-cost, broad-based index funds, which simply buy and hold all the stocks in the market as a whole. As more and more evidence accumulates, we have become more convinced than ever of the effectiveness of index funds. Over 10-year periods, broad stock market index funds have regularly outperformed two-thirds or more of the actively managed mutual funds.

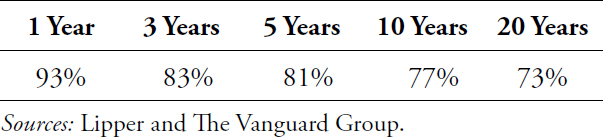

And the amount by which index funds trounce the typical mutual fund manager is staggeringly large. The following table compares the performance of active managers of broadly diversified mutual funds with the Standard & Poor's (S&P) 500 stock index of the largest corporations in the United States. Each decade about three-quarters of the active managers must hang their heads in shame for being beaten by the popular stock market index.

Percentage of Actively Managed Mutual Funds Outperformed by the S & P 500 Index (Periods through June 30, 2012)

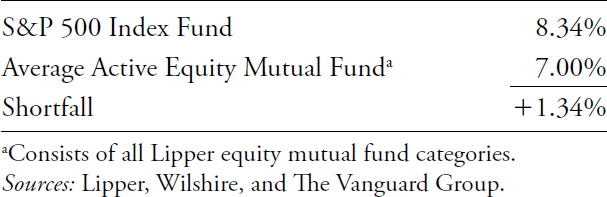

The superiority of indexing as an investment strategy is further demonstrated by comparing the percentage returns earned by the typical actively managed mutual fund with a mutual fund that simply invests in all 500 stocks included in the S&P 500 stock index. The table on the following page shows that the index fund beats the average active fund by more than a full percentage point per year, year after year.*

Average Annual Returns of Actively Managed Mutual Funds Compared with S & P 500

20 years, Ending June 30, 2012

Why does this happen? Are the highly paid professional managers incompetent? No, they certainly are not.

Here's why investors as a total group cannot earn more than the market return. All the stocks that are outstanding need to be held by someone. Professional investors as a whole are responsible for about 90 percent of all stock market trading. While the ultimate holders may be individuals through their pension plans, 401(k) plans, or IRAs, professional managers, as a group, cannot beat the market because they are the market.

Because the players in the market must, on average, earn the market return and winners’ winnings will equal losers’ losses, investing is called a zero-sum game. If some investors are fortunate enough to own only the stocks that have done better than the overall market, then it must follow that some other investors must be holding the stocks that have done worse. We can't and don't live in Garrison Keillor's mythical Lake Wobegon, where everybody is above average.

But why do professionals as a group do worse than the market? In fact, they do earn the market return—before expenses. The average actively managed mutual fund charges about one percentage point of assets each year for managing the portfolio. It is the expenses charged by professional “active” managers that drag their return well below that of the market as a whole.

Low-cost index funds charge only one-tenth as much for portfolio management. Index funds do not need to hire highly paid security analysts to travel around the world in a vain attempt to find “undervalued” securities. In addition, actively managed funds tend to turn over their portfolios about once a year. This trading incurs the costs of brokerage commissions, spreads between bid and asked prices, and “market impact costs” (the effect of big buy or sell orders on prices). Professional managers underperform the market as a whole by the amount of their management expenses and transaction costs. Those costs go into the pockets of the croupiers of the financial system, not into your retirement funds. That's why active managers do not beat the market—and why the market beats them.

DON'T SOME BEAT THE MARKET?

Don't some managers beat the market? We often read about those rare investment managers who have managed to beat the market over the last quarter, or the last year, or even the last several years. Sure, some managers do beat the market—but that's not the real question. The real question is this: Will you, or anyone else, be able to pick the managers who will beat the market in advance?

That's a really tough one. Here's why:

- Only a few managers beat the market. Since 1970, you can count on the fingers of one hand the number of managers who have managed to beat the market by any meaningful amount. And chances are that as more and more ambitious, skillful, hard-working managers with fabulous computer capabilities join the competition for “performance,” it will continue to get harder and harder for any one professional to do better than the other pros who now do 95 percent of the daily trading.

- Nobody—repeat, nobody—has been able to figure out in advance which funds will do better. The failure to forecast certainly includes all the popular public rating sources, including Morningstar.

- Funds that beat the market “win” by less than those that got beaten by the market “lose.” This means that fund buyers’ “slugging percentage” is even lower than the already discouraging win-loss ratio.

The only forecast based on past performance that works is the forecast of which funds will do badly. Funds that have done really poorly in the past do tend to perform poorly in the future. Talk about small consolation! And the reason for this persistence is that it is typically the very high-cost funds that show the poorest relative performance, and—unlike stock picking ability—those high investment fees do persist year after year.

The financial media are quick to celebrate managers who have recently beaten the market as investment geniuses. These investment managers appear on TV opining confidently about the direction of the market and about which stocks are particularly attractive for purchase. Should we then place our bets on the stock jockeys who have recently been on a hot streak? No, because there is no long-term persistence to above-average performance. Just because a manager beat the market last year does not mean he or she is likely to continue to do so again next year. The probability of continuing a winning streak is no greater than the probability of flipping heads in the next fair toss of a coin, even if you have flipped several heads in a row in your previous tosses. The top-rated funds in any decade bear no resemblance to the top-rated funds in the next decade. Mutual fund “performance” is almost as random as the market.

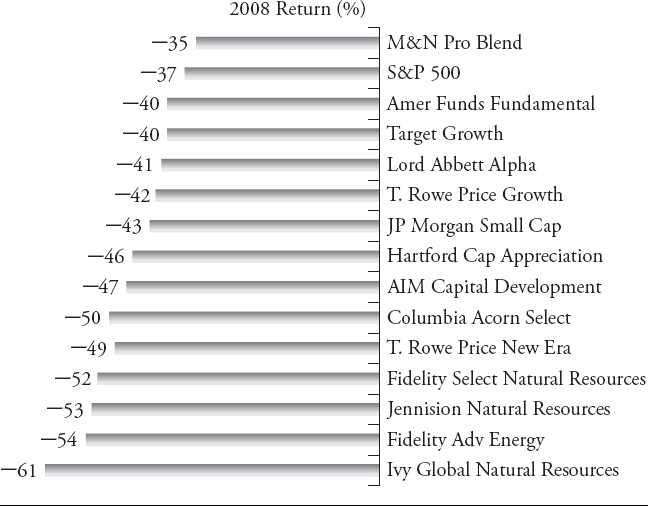

The Wall Street Journal provided an excellent example in January 2009 of how ephemeral “superior” investment performance can be. During the nine-year period through December 31, 2007, 14 equity mutual funds had managed to beat the S&P 500 for nine years in a row. Those funds were advertised to the public as the best vehicles for individual investors. How many of those funds do you think managed to beat the market in 2008? As the figure above shows, there was only one out of 14. Study after study comes to the same conclusion. Chasing hot performance is a costly and self-defeating exercise. Don't do it!

And Then There Was One

Source: Wall Street Journal, January 5, 2009. Reprinted with permission of the Wall Street Journal, copyright © 2009 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

License number 2257121352481.

Are there any exceptions to the rule? Of all the professional money managers, Warren Buffett's record stands out as the most extraordinary. For over 40 years, Buffett's company, Berkshire Hathaway, has earned a rate of return for his stockholders twice as large as the stock market as a whole. But that record was not achieved only by his ability to purchase “undervalued” stocks, as it is often portrayed in the press. Buffett buys companies and holds them. (He has suggested that the correct holding period for a stock is forever.) And he has taken an active role in the management of the companies in which he has invested, such as the Washington Post, one of his earliest successes. And he uses the ‘float’ from insurance operations to get low-cost financial leverage. Even Buffett has suggested that most people would be far better off simply investing in index funds. So has David Swensen, the brilliant portfolio manager for the Yale University endowment fund.

We are convinced there will be “another Warren Buffett” over the next 40 years. There may even be several of them. But we are even more convinced we will never know in advance who they will be. As the previous figure makes clear, past performance is an unreliable guide to the future. Finding the next Warren Buffett is like looking for a needle in a haystack. We recommend that you buy the haystack instead, in the form of a low-cost index fund.

INDEX BONDS

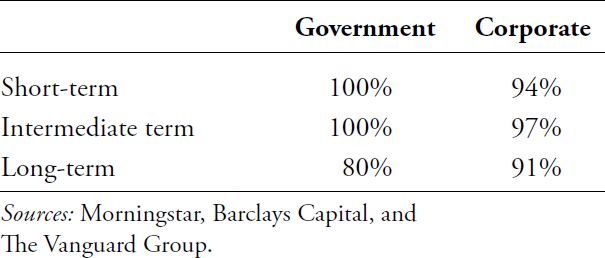

If indexing has advantages in the stock market, its superiority is even greater in the bond market. You would never want to hold just one bond (such as an IOU from General Motors or Chrysler) in your portfolio—any single bond issuer could get into financial deficiency and be unable to repay you in full. That's why you need a broadly diversified portfolio of bonds—making a mutual fund essential. And it's wise to use bond index funds: They have regularly proved superior to actively managed bond funds. The table shows that the vast majority of actively managed bond funds have been beaten by bond index funds, particularly in the short-term and intermediate maturities.

Percentage of Actively Managed Bond Funds Outperformed by Government- and Corporate-Bond Indexes (10 years through June 30, 2012)

INDEX INTERNATIONALLY

Indexing has also proved its merits in non-U.S. markets. Most global equity managers have been outperformed by a low-cost index fund that buys all the stocks in the MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australasia, and Far East) index of non-U.S. stocks in developed markets. Even in the less efficient emerging markets, index funds regularly outperform active managers. The very inefficiency of the trading markets in many emerging markets (lack of liquidity, large bid-ask spreads, high transaction costs) makes a high-turnover, active management investment strategy inadvisable. Indexing has even worked well in markets such as China, where there have apparently been many past instances of market manipulation.

INDEX FUNDS HAVE BIG ADVANTAGES

A major advantage of indexing is that index funds are tax efficient. Actively managed funds can create large tax liabilities if you hold them outside your tax-advantaged retirement plans. To the extent that your funds generate capital gains from their portfolio turnover, this active trading creates taxable income for you. And short-term capital gains are taxed at ordinary income tax rates that can go well over 50 percent when state income taxes are considered. Index funds, in contrast, are long-term buy-and-hold investors and typically do not generate significant capital gains or taxable income. To overcome the drag of expenses and taxes, an actively managed fund would have to outperform the market by 4.3 percentage points per year just to break even with index funds.* The odds that you can find an actively managed mutual fund that will perform that much better than an index fund are virtually zero.

Let's summarize the advantages of index funds. First, they simplify investing. You don't need to evaluate the thousands of actively managed funds and somehow pick the best. Second, index funds are cost efficient and tax efficient. (Active managers’ trading in and out of securities can be costly and will tend to increase your capital gains tax liability.) Finally, they are predictable. While you are sure to lose money when the market declines, you won't end up doing far more poorly than the market, as many investors did when their mutual fund managers loaded up with Internet stocks in early 2000 or with bank stocks in 2008. Investing in index funds won't permit you to boast at the golf club or at the beauty parlor that you were able to buy an individual stock or fund that soared. That's why critics like to call indexing “guaranteed mediocrity.” But we liken it to playing a winner's game where you are virtually guaranteed to do better than average, because your return will not have been dragged down by high investment costs.

ONE WARNING

Not all index funds are created equal, however. Beware: Some index funds charge unconscionably high management fees. We believe you should buy only those domestic common-stock funds that charge one-fifth of 1 percent or less annually as management expenses. And while the fees for investing in international funds tend to be higher than for U.S. funds, we believe you should limit yourself to the lowest-cost international index funds as well. (We list our specific recommendations in a later chapter.)

You may also want to consider exchange-traded index funds, or ETFs. These are index funds that trade on the major stock exchanges and can be bought and sold like stocks. ETFs are available for broad U.S. and foreign indexes as well as for various market sectors. They have some advantages over mutual funds. They often have even lower expense ratios than index funds. They also allow an investor to buy and sell at any time during the day (rather than once a day at closing prices) and thus are favored by professional traders for hedging. Finally, they can be even more tax efficient than mutual funds since they can redeem shares without generating a taxable event.

ETFs are not suitable, however, for individuals making periodic payments into a retirement plan such as an IRA or 401(k) because each payment will incur a brokerage charge that could be a substantial percentage of small contributions. With no-load index funds, no transaction fees are levied on contributions. Moreover, mutual funds will automatically reinvest all dividends back into the fund whereas additional transactions could be required to reinvest ETF dividends. We recommend that individuals making periodic contributions to a retirement plan use low-cost indexed mutual funds rather than ETFs.

Let's wrap up this chapter on index funds with two more pieces of advice. The first concerns how an investor should choose among different types of broad-based index funds. The best-known of the broad stock market mutual funds and ETFs in the United States track the S&P 500 index of the largest stocks. We prefer using a broader index that includes more smaller-company stocks, such as the Russell 3000 index or the Dow-Wilshire 5000 index. Funds that track these broader indexes are often referred to as “total stock market” index funds. More than 80 years of stock market history confirm that portfolios of smaller stocks have produced a higher rate of return than the return of the S&P 500 large-company index. While smaller companies are undoubtedly less stable and riskier than large firms, they are likely—on average—to produce somewhat higher future returns. Total stock market index funds are the better way for investors to benefit from the long-run growth of economic activity.

We have one final piece of advice for those stock market junkies who feel that, despite all the evidence to the contrary, they really do know more than the market does. If you must try to beat the market by identifying the next Google or the next Warren Buffett, we are not about to insist that you not do it. Your odds of success are at least better in the stock market than at the racetrack or gambling casino, and investing in individual stocks can be a lot of fun. But we do advise you to keep your serious retirement money in index funds. Do what professional investors increasingly do: Index the core of your portfolio and then, if you must, make individual bets around the edges. But have the major core of your investment—and especially your retirement funds—in a well-diversified set of stock and bond index funds. You can then “play the market” with any extra funds you have with far less risk that you will undermine your chances for a comfortable and worry-free retirement.

CONFESSION

Nobody's perfect. We certainly aren't. For example, one of us has a major commitment to the stock of a single company—an unusual company called Berkshire Hathaway. He has owned it for 35 years and has no intention to sell. If that's bad enough, ponder this: He checks the price almost every day! Of course, it's nuts—and he knows it, but just can't help himself. Another example: The other author delights in buying individual stocks and has a significant commitment to China. He enjoys the game of trying to pick winners and believes “China” is a major story for his grandchildren. (Please note, in both cases, our retirement funds are safely indexed—and our children use index funds, too!)