IV

AVOID BLUNDERS

You, far more than the market or the economy, are the most important factor in your long-term investment success.

We're both in our seventies. America's favorite investor, Warren Buffett, is in his early eighties. The main difference between his spectacular results and our good results is not the economy and not the market, but the man from Omaha. He is simply a better investor than just about any other investor in the world, amateur or professional. Brilliant, consistently rational, and blessed with a superb mind for business, he concentrates more time and effort on being a better investor and is more disciplined.

One of the major reasons for Buffett's success is that he has managed to avoid the major mistakes that have crushed so many portfolios. Let's look at two examples. In early 2000, many observers declared that Buffett had somehow lost his touch. His Berkshire Hathaway portfolio had underperformed the popular high-tech funds that enjoyed spectacular returns by loading up on stocks of technology companies and Internet startups. Buffett avoided all tech stocks. He told his investors that he refused to invest in any company whose business he did not fully understand—and he didn't claim to understand the complicated, fast-changing technology business—or where he could not figure out how the business model would sustain a growing stream of earnings. Some said he was passé, a fuddy-duddy. Buffett had the last laugh when Internet-related stocks came crashing back to earth.

In 2005 and 2006, Buffett largely avoided the popular complex mortgage-backed securities and the derivatives that found their way into many investment portfolios. Again, his view was that they were too complex and opaque. He called them “financial weapons of mass destruction.” When in 2007 they brought down many a financial institution (and ravaged our entire financial system), Berkshire Hathaway avoided the worst of the financial meltdown.

Avoiding serious trouble, particularly troubles that come from incurring unnecessary risks, is one of the great secrets to investment success. Investors all too often beat themselves by making serious—and completely unnecessary—investment mistakes. In this chapter, we highlight the common investment mistakes that can prevent you from realizing your goals.

As in so many human endeavors, the secrets to success are patience, persistence, and minimizing mistakes.

As in so many human endeavors, the secrets to success are patience, persistence, and minimizing mistakes. In driving, it's having no serious accidents; in tennis, the key is getting the ball back; and in investing, it's indexing—to avoid the expenses and mistakes that do so much harm to so many investors.

OVERCONFIDENCE

In recent years, a group of behavioral psychologists and financial economists have created the important new field of behavioral finance. Their research shows that we are not always rational and that in investing, we are often our worst enemies. We tend to be overconfident, harbor illusions of control, and get stampeded by the crowd. To be forewarned is to be forearmed.

At our two favorite universities, Yale and Princeton, psychologists are fond of giving students questionnaires asking how they compare with their classmates in respect to different skills. For example, students are asked: “Are you a more skillful driver than your average classmate?” Invariably, the overwhelming majority answer that they are above-average drivers compared with their classmates. Even when asked about their athletic ability, where one would think it was more difficult to delude oneself, students generally think of themselves as above-average athletes, and they see themselves as above-average dancers, conservationists, friends, and so on.

And so it is with investing. If we do make a successful investment, we confuse luck with skill. It was easy in early 2000 to delude yourself that you were an investment genius when your Internet stock doubled and then doubled again. The first step in dealing with the pernicious effects of overconfidence is to recognize how pervasive it is. In amateur tennis, the player who steadily returns the ball, with no fancy shots, is usually the player who wins. Similarly, the buy-and-hold investor who prudently holds a diversified portfolio of low-cost index funds through thick and thin is the investor most likely to achieve her long-term investment goals.

Investors should avoid any urge to forecast the stock market. Forecasts, even forecasts by recognized “experts,” are unlikely to be better than random guesses. “It will fluctuate,” declared J. P. Morgan when asked about his expectation for the stock market. He was right. All other market forecasts—usually estimating the overall direction of the stock market—are historically about 50 percent right and 50 percent wrong. You wouldn't bet much money on a coin toss, so don't even think of acting on stock market forecasts.

Why? Forecasts of many “real economy” developments based on hard data are wonderfully useful. So are weather forecasts. Market forecasting is many times more difficult. Market forecasts have a poor record because the market is already the aggregate result of many, many well-informed investors making their best estimates and expressing their views with real money. Predicting the stock market is really predicting how other investors will change the estimates they are now making with all their best efforts. This means that, for a market forecaster to be right, the consensus of all others must be wrong and the forecaster must determine in which direction—up or down—the market will be moved by changes in the consensus of those same active investors.

Warning: As human beings, we like to be told what the future will bring. Soothsayers and astrologists have made forecasts throughout history. A panoply of genial myths have been part of the human experience for centuries—and we're all still human. Buildings don't have a 13th floor; we avoid walking under ladders, toss salt over our shoulders, and don't step on cracks in the sidewalk. “Que sera, sera” has charm as a tune, but it gives no real satisfaction.

The largest, longest study of experts' economic forecasts was performed by Philip Tetlock, a professor at the Haas Business School of the University of California–Berkeley. He studied 82,000 predictions over 25 years by 300 selected experts. Tetlock concludes that expert predictions barely beat random guesses. Ironically, the more famous the expert, the less accurate his or her predictions tended to be.

So, as an investor, what should you do about forecasts—forecasts of the stock market, forecasts of interest rates, forecasts of the economy? Answer: Nothing. You can save time, anxiety, and money by ignoring all market forecasts.

As an investor, what should you do about forecasts—forecasts of the stock market, forecasts of interest rates, forecasts of the economy? Answer: Nothing. You can save time, anxiety, and money by ignoring all market forecasts.

BEWARE OF MR. MARKET

As people, we feel safety in numbers. Investors tend to get more and more optimistic, and unknowingly take greater and greater risks, during bull markets and periods of euphoria. That is why speculative bubbles feed on themselves. But any investment that has become a widespread topic of conversation among friends or has been hyped by the media is very likely to be unsuccessful.

Throughout history, some of the worst investment mistakes have been made by people who have been swept up in a speculative bubble. Whether with tulip bulbs in Holland during the 1630s, real estate in Japan during the 1980s, or Internet stocks in the United States during the late 1990s, following the herd—believing “this time it's different”—has led people to make some of the worst investment mistakes. Just as contagious euphoria leads investors to take greater and greater risks, the same self-destructive behavior leads many investors to throw in the towel and sell out near the market's bottom when pessimism is rampant and seems most convincing.

One of the most important lessons you can learn about investing is to avoid following the herd and getting caught up in market-based overconfidence or discouragement. Beware of “Mr. Market.”

First described by Benjamin Graham, the father of investment analysis, two mythical characters compete for our attention as investors.* One is Mr. Market and one is Mr. Value. Mr. Value invents, manufactures, and sells all the many goods and services we all need. Working hard at repetitive and often boring tasks, conscientious Mr. Value beavers away day and night making our complex economy perform millions of important functions day after day. He's seldom exciting, but we know we can count on him to do his best to meet our wants.

While Mr. Value does all the work, Mr. Market has all the fun. Mr. Market has two malicious objectives. The first is to trick investors into selling stocks or mutual funds at or near the market bottom. The second is to trick investors into buying stocks or mutual funds at or near the top. Mr. Market tries to trick us into changing our investments at the wrong time—and he's really good at it. Sometimes terrifying, sometimes gently charming, sometimes compellingly positive, sometimes compelling negative, but always engaging, this malicious, high-maintenance economic gigolo has only one objective: to cause you to do something. Make changes, buy or sell—anything will do if you'll just do something. And then do something else. The more you do, the merrier he will be.

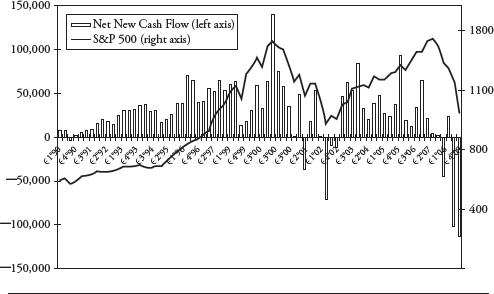

Mr. Market is expensive and the cost of transactions is the small part of the total cost. The large part of the total cost comes from the mistakes he tricks us into making—buying high and selling low. Look at the crafty devil's record of success. Here's how he has been tricking investors as a whole. In the next figure we superimpose the flows of money going into equity mutual funds against the general level of market prices. The lesson is unmistakable. Money flows into the funds when prices are high. Investors pour money into equity mutual funds at exactly the wrong time.

More money went into equity mutual funds during the fourth quarter of 1999 and the first quarter of 2000—just at the top of the market—than ever before. And most of the money that went into the market was directed to the high technology and Internet funds—the stocks that turned out to be the most overpriced and then declined the most during the subsequent bear market. And more money went out of the market during the third quarter of 2002 than ever before, as mutual funds were redeemed or liquidated—just at the market trough. Note also that during the punishing bear market of 2007–2008, new record withdrawals were made by investors who threw in the towel and sold their mutual fund shares—at record lows—just before the first, and often best, part of a market recovery.

Cash Flow to Equity Funds Follows the Stock Market

Source: The Vanguard Group.

It's not today's price or even next year's price that matters; it's the price you'll get when it's your time to sell to provide spending money during your years of retirement. For most investors, retirement is a long way off in the future. Indeed, when pessimism is rampant and market prices are down is the worst time to sell out or to stop making regular investment contributions. The time to buy is when stocks are on sale.

Investing is like raising teenagers—“interesting” along the way as they grow into fine adults. Experienced parents know to focus on the long term, not the dramatic daily dust-ups. The same applies to investing. Don't let Mr. Market trick you into either exuberance or distress. Just as you do when the weather is really extreme, remember the ancient counsel, “This too shall pass.”

You don't care if it's cold and raining or warm and sunny 10,000 miles away because it's not your weather. The same detachment should apply to your 401(k) investments until you approach retirement. Even at age 60, chances are you will live another 25 years and your spouse may live several years more.

THE PENALTY OF TIMING

Does the timing penalty—the cost of second-guessing the market—make a big difference? You bet it does. The stock market as a whole has delivered an average rate of return of about 9½ percent over long periods of time. But that return only measures what a buy-and-hold investor would earn by putting money in at the start of the period and keeping her money invested through thick and thin. In fact, the returns actually earned by the average investor are at least two percentage points—almost one-fourth—lower because the money tends to come in at or near the top and out at or near the bottom.*

In addition to the timing penalty, there is also a selection penalty. When money poured into equity mutual funds in late 1999 and early 2000, most of it went to the riskier funds—those invested in high tech and Internet stocks. The staid “value” funds, which held stocks selling at low multiples of earnings and with high dividend yields, experienced large withdrawals. During the bear market that followed, these same value funds held up very well while the “growth” funds suffered large price declines. That's why the gap between the actual returns of investors and the overall market returns is even larger than the two percentage point gap cited earlier.

Fortunately, there's hope. Mr. Market can only hurt us if we let him. That's why we all need to learn that getting tricked or duped by Mr. Market is actually our fault. As Mom said, we can only get teased or insulted or hurt by bad people if we let them. As an investor, you have one powerful way to keep from getting distressed by devilish Mr. Market: Ignore him. Just buy and hold one of the broad-based index funds that we list on pages 117–119.

MORE MISTAKES

Psychologists have identified a tendency in people to think they have control over events even when they have none. For investors, such an illusion can lead them to overvalue a losing stock in their portfolio. It also can lead people to imagine there are trends when none exist or believe they can spot a pattern in a stock price chart and thus predict the future. Charting is akin to astrology. The changes in stock prices are very close to a “random walk”: There is no dependable way to predict the future movements of a stock's price from its past wanderings.

The same holds true for supposed “seasonal” patterns, even if they appear to have worked for decades in the past. Once everyone knows there is a Santa Claus rally in the stock market between Christmas and New Year's Day, the “pattern” will evaporate. This is because investors will buy one day before Christmas and sell one day before the end of the year to profit from the supposed regularity. But then investors will have to jump the gun even earlier, buying two days before Christmas and selling two days before the end of the year. Soon all the buying will be done well before Christmas and the selling will take place right around Christmas. Any apparent stock market “pattern” that can be discovered will not last—as long as there are people around who will try to exploit it.

Psychologists also remind us that investors are far more distressed by losses than they are delighted by gains. This leads people to discard their winners if they need cash and hold onto their losers because they don't want to recognize or admit that they made a mistake. Remember: Selling winners means paying capital gains taxes while selling losers can produce tax deductions. So if you need to sell, sell your losers. At least that way you get a tax deduction rather than an increase in your tax liability.

MINIMIZE COSTS

There is one investment truism that, if followed, can dependably increase your investment returns: Minimize your investment costs. We have spent two lifetimes thinking about which mutual fund managers will have the best performance year in and year out. Here's what we now know: It was and is hopeless.

There is one investment truism that, if followed, can dependably increase your investment returns: Minimize your investment costs.

Here's why: Past performance is not a good predictor of future returns. What does predict investment performance are the fees charged by the investment manager. The higher the fees you pay for investment advice, the lower your investment return. As our friend Jack Bogle likes to say: In the investment business, “You get what you don't pay for.”

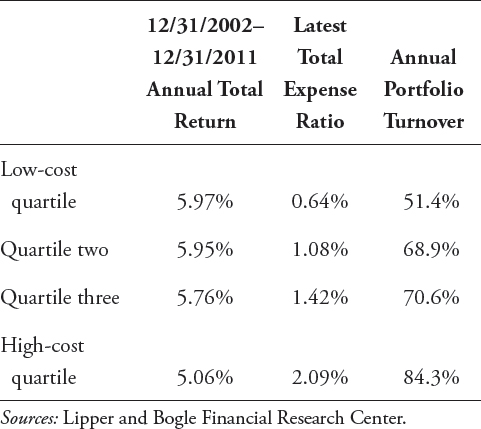

Let's demonstrate this proposition with the simple table shown on page 89. We look at all equity mutual funds over a 10-year period and measure the rate of return produced for their investors as well as all the costs charged and the implicit costs of portfolio turnover—the cost of buying and selling portfolio holdings. We then divide the funds into quartiles and show the average returns and average costs for each quartile. The lowest-cost quartile funds produce the best returns.

If you want to own a mutual fund with top quartile performance, buy a fund with low costs. Of course, the quintessential low-cost funds are the index funds we recommend throughout this book. If we measure after-tax returns, recognizing that high turnover funds tend to be tax inefficient, our conclusion holds with even greater force.

Costs and Net Returns: All General Equity Funds

While we are on the subject of minimizing costs, we need to warn you to beware of stockbrokers. Brokers have one priority: to make a good income for themselves. That's why they do what they do the way they do it. The stockbroker's real job is not to make money for you but to make money from you. Of course, brokers tend to be nice, friendly, and personally enjoyable for one major reason: Being friendly enables them to get more business. So don't get confused. Your broker is your broker—period.

The typical broker “talks to” about 75 customers who collectively invest about $ 40 million. (Think for a moment about how many friends you have and how much time it takes you to develop each of those friendships.) Depending on the deal he has with his firm, your broker gets about 40 percent of the commissions you pay. So if he wants a $ 100,000 income, he needs to gross $ 250,000 in commissions charged to customers. Now do the math. If he needs to make $ 200,000, he'll need to gross $ 500,000. That means he needs to take that money from you and each of his other customers. Your money goes from your pocket to his pocket. That's why being “friends” with a stockbroker can be so expensive. Like Mr. Market, a broker has one priority: Getting you to take action, any action.

We urge you not to engage in “gin rummy” behavior. Don't jump from stock to stock or from mutual fund to fund as if you were selecting and discarding cards in a gin rummy game and thereby running up your commission costs (and probably adding to your tax bill as well). In fact, we don't think individual investors should try to buy individual stocks or try to pick particular actively managed mutual funds. Buy and hold a low-cost, broad-based index fund and you are likely to enjoy well-above-average returns because of the low costs you pay.