VI

TIMELESS LESSONS FOR TROUBLED TIMES

Since Elements was first written, investors have lived through harrowing economic times, with unprecedented market volatility. Toward the end of the first decade of the 2000s, it appeared to some observers that the financial system was likely to self-destruct and that capitalism was running in reverse. Rather than “the Great Moderation,” the label often given to the stability of the preceding period, the faltering economy engendered comparisons with the Great Depression of the 1930s. Many European nations suffered a debt crisis, and the very viability of the Eurozone was widely debated. The stock market lost half of its value. The entire decade was often referred to as “the lost decade” for investors.

It is not surprising, then, that many investors simply abandoned the stock market. The volatility was just too frightening for many people. The stock market seemed to be too risky a place for retirement savings, too unnerving for ordinary investors to handle. Moreover, some professionals, particularly those whose financial interest was enhanced by frequent trading, announced the death of “buy and hold” and proclaimed that the only way to be a successful investor was to “time the market.” “Diversification is dead” was another common bromide. “Today's stock markets are too highly correlated,” so-called experts said. When markets go down, “there is no place to hide.” Small wonder that investors could get thoroughly confused as they listened to this often-conflicted advice.

We disagree. We believe that the timeless investment lessons presented in this book are even more relevant in today's volatile markets. We believe that short-term volatility does not represent real risk for the average investor accumulating a retirement nest egg over many years. Indeed, volatility can be your friend and actually enhance returns for the disciplined long-term investor who is saving regularly, while those investors who attempt market timing all too often make the worst mistakes at the worst times.

Anyone who tries to time the market is usually his own worst enemy. Anxious investors almost invariably do the wrong thing, converting short-term modest losses into long-term permanent losses, resulting in a major investment blunder. The behavior of many investors during market crises convinces us more than ever of the folly of market timing. We've seen it many times. During the Internet Bubble that peaked in early 2000, overly optimistic investors poured their savings into Internet stocks. Just as the financial crisis was at its peak and the stock markets of the world hit bottom in 2008, individuals pulled more money than ever before out of the stock market rather than taking advantage of the bargain prices and putting money in. The same happened at the market bottom in 2011 when Europe was the epicenter of the financial meltdown.

Diversification, and the rebalancing strategies we advocate in Elements, are time-tested strategies that really do reduce investment risk.* Because we think these timeless lessons are so important during times like this—when markets are unstable and there is such a cacophony of bad advice bombarding the average investor—we have added this brief final chapter.

VOLATILITY AND DOLLAR-COST AVERAGING

The volatility of equity markets can be turned to advantage for savers who are long-term investors who will be accumulating a retirement nest egg over time through periodic investments—such as individuals with 401(k) plans. These investors will be taking advantage of the dollar-cost averaging described in Chapter III. In introducing this simple, time-tested technique, we showed that a patient investor can actually build up a larger retirement fund in a volatile flat market than in a market that is continuously rising.

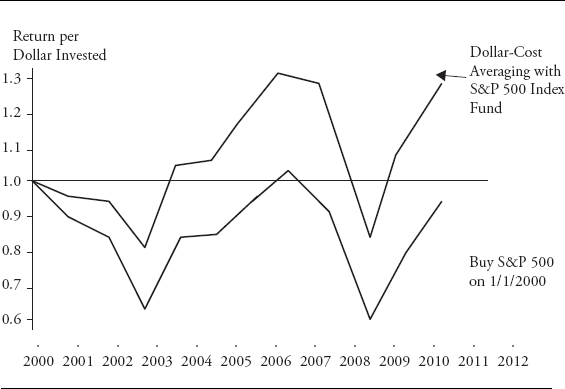

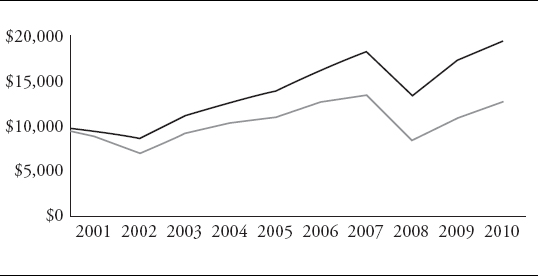

Moving from the hypothetical calculations shown earlier, here's an actual illustration of how the strategy of consistent investment in equities can produce a growing retirement fund—even when the stock seems to simply tread water for a period of a decade or more. The first decade of the 2000s was one of the toughest investment decades in history. Early in the decade, the market suffered a 50 percent decline as the Internet Bubble of the late 1990s burst. Later in the decade, the global financial crisis wreaked havoc on investors as stock prices declined by almost 50 percent again. At the end of 2010, the stock market index, as measured by the Standard and Poor's (S&P) 500 stock index, was actually lower than it was at the beginning of the decade in January 2000. This kind of experience soured millions of Americans on investing in stocks. But was it really so bad for savers who followed the rules we espouse?

In the following illustration, we assume that the investor starts her program in January 2000. Her timing was perfectly terrible since market prices then were at a historical peak. But despite losing about half of her initial investment, she has the self-discipline, clarity of purpose, and perseverance to continue to invest in each and every period—“good” times and “bad.” To keep the calculations simple we assume that $1,000 per year is invested and that the investment is made only once a year on the first trading day of January. We also assume that dividends are reinvested. The table below uses actual values for the S&P 500 stock index.

The remarkable conclusion is that even during a decade that was disastrous for many equity investors, our dollar-cost averaging investor enjoyed a moderate positive return and was able to enhance the final value of her retirement nest egg. We believe that equity markets will continue to exhibit substantial short-term volatility in the future. For the long-term investors, that short-term volatility may be an annoyance, but it is not a major problem: It's an opportunity. Long-term investors can and should look beyond the inevitable market ups and downs. The major risk for long-term investors hoping to enjoy a comfortable retirement is not having to endure the ups and downs of stock prices; the risk for long-term investors is letting the volatility of the markets keep them from a regular program of buying equities. Dollar-cost averaging is one of the long-term investor's four best friends.

Dollar-Cost Averaging During the “Lost Decade”

DIVERSIFICATION IS STILL A TIME-HONORED STRATEGY TO REDUCE RISK

Diversification is the time-honored way to reduce investment risk. Diversification is as basic to successful investing as good health is to a great life. The general idea is to include in your portfolio some asset types that provide a degree of stability during the inevitable equity bear markets. But even diversification has been challenged during the recent difficult times in the stock market. There are, of course, a few kernels of truth in arguments of the “naysayers” who say that diversification fails us just when we need it most. Stock markets in different national markets have become much more highly correlated. Globalization has tended to make the stock markets in different countries go up and down together. Abrupt market declines around the world are more synchronous. Despite the plausibility of these arguments, diversification remains an extraordinarily useful technique to achieve your investment goals. Diversification is another one of the long-term investor's best friends.

First, not all financial assets go up and down together. For example, bond prices have often risen when stock prices fell. If a recession is expected, corporate earnings can be expected to decline, so stock prices are likely to fall. But the monetary authorities typically try to reduce the severity of the recession by lowering interest rates, and when rates fall, bond prices rise. Thus bonds often zig just when stock prices zag, imparting a degree of stability to your overall portfolio. In fact, in recent years, returns from stocks and bonds have tended to move in opposite directions. (Later in the chapter we have more to say about bonds in the current environment.)

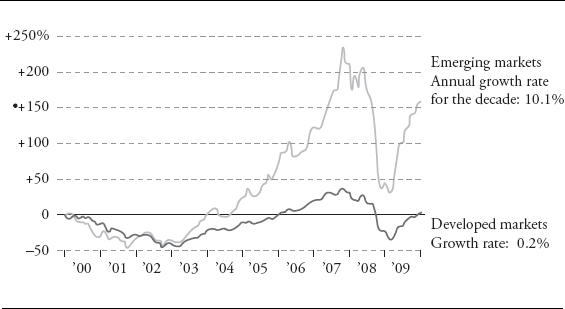

Moreover, even when equity markets around the world tend to move up and down almost in unison, there have been vast differences in the performance of different stock markets. While the short-term fluctuations in developed and emerging equity markets were almost perfectly correlated during the first decade of the 2000s, the long-term performance of those markets was vastly different. Developed markets were basically flat during the decade, producing a minuscule rate of return, but emerging markets produced an overall return for investors of 10 percent per year compounded.

Diversification into Emerging Markets Helped during the Lost Decade

Sources: MSCI and Bloomberg.

REBALANCING

We want to reemphasize that the timeless lesson of rebalancing covered in Chapter III proved its value very well—especially during the most volatile periods of the market. Recall that rebalancing simply means that periodically, such as once a year, you look at the asset allocation of your portfolio and bring it back into the kind of balance that makes you comfortable. For example, suppose you are a “nervous Nelson” and prefer not to have equities be more than 50 percent of your portfolio—with bonds comprising the other half. Rebalancing says simply that if equity prices rise and bond prices fall, so that your portfolio has become 70 percent stocks and 30 percent bonds, you should sell some stocks and buy some bonds to restore the balance you desire, because it's consistent with the risk level that is right for you.

The chart on page 137 demonstrates the benefits of rebalancing a 60–40, stock–bond portfolio. Notice that annual rebalancing added almost 1½ percentage points of return per year over a 15-year period—and the stability of the annual return improved as well. You may wonder what alchemy could have improved the return so much. The answer is that rebalancing makes you take some profits in the asset class that has done particularly well and invest in the one that has become a better bargain.

If you think of what was happening to markets over the period, it is very clear why the technique worked so well. The rebalancing was done every January. In January 2000, no one knew that the Internet Bubble would burst in March of that year. But you did know that the equity prices had risen sharply in the market euphoria and that rising interest rates were causing bond prices to fall. So the unintended allocation in January had become close to 75 percent stocks and 25 percent bonds rather than the intended 60–40 mix. To rebalance, some stocks were sold and the money invested in bonds to restore the balance. Now think of January 2003—after the market had tumbled sharply and interest rates had fallen, leading to rising bond prices. No one knew that the stock market had made a bottom in October 2002, but you would have seen that bonds were then 55 percent of the portfolio, well above the target allocation. So bonds were sold and stocks were bought. During the global financial crisis, toward the end of the first decade of the 2000s, rebalancing again worked for you. Interest rates had been driven down to near zero on Treasury securities, so the portfolio in January 2009 had become overweighted with bonds and underweighted with equities. It was time to rebalance again.

What rebalancing forces you to do is the very opposite of what most investors do. Most investors tend to buy at market tops when everyone is optimistic and sell at the bottom when it appears that the sky is falling. (That is, of course, what creates market tops and bottoms.) Rebalancing forces you to do the opposite. Disciplined rebalancing is another of the long-term investor's best friends.

DIVERSIFICATION AND REBALANCING TOGETHER

Burt has for years proposed* for an investor in his or her 50s a diversified portfolio of 33 percent bonds, 33 percent U.S. stocks, 17 percent foreign developed market stocks, and 17 percent emerging market stocks. (This was meant to be only a rough guideline.) All investors are different in their capacity for taking risk and their willingness to assume it. Charley's view is that a starting point would be only a 20 percent allocation to bonds. Whatever the allocation, the rebalancing strategy we both recommend would produce the same kind of benefits shown in the illustration that follows. The chart shows the performance of Burt's portfolio contrasted with a nondiversified purely U.S. domestic stock portfolio. The undiversified domestic portfolio was basically flat throughout the “lost” first decade of the 2000s. But the diversified portfolio, annually rebalanced, despite the very poor performance of the stock markets in the major developed countries of the world, almost doubled in value.

Advantages of Diversification and Rebalancing

Source: Vanguard and Morningstar.

INDEX AT LEAST THE CORE OF YOUR PORTFOLIO

The difficult market environment since the first edition of Elements also reinforces for us the message of Chapter II—use index funds for most, if not all, of your portfolio of financial assets. “Beating the market,” of course, means outperforming the consensus of many hardworking and well-informed professional competitors. Changes in the market—due to changes in market participants—have been substantial, particularly in the aggregate. Over the past 50 years, trading volume has increased 2,000 times—from 2 million shares a day to 4 billion—while the dollar value of derivatives traded (options, swap contracts, etc.) in value traded, has gone from zero to even more than the primary markets in stocks and bonds.

Most importantly, the worldwide increase in the number of highly trained experts working intensively to achieve any competitive advantage has been phenomenal. The enormous increase in competition by several hundred thousand well-informed, tech-savvy, hardworking professionals at the world's major institutions has surely made it increasingly difficult for any one investor to outperform the market benchmark. As a result, like a gigantic prediction market, today's stock market expresses all of the expert estimates of value coming every day from an extraordinary number of independent, experienced, and competitive decision makers. Against this consensus of experts, any manager of a diversified portfolio of publicly traded securities is deeply challenged. Extensive, undeniable data show how improbable it is that any particular investment manager can be identified in advance who will—after costs, taxes, and the fees now charged—achieve the Holy Grail of beating the market. Yes, Virginia, there have been a very few managers who have beaten the market over time, but nobody has found a reliable way of determining in advance which specific managers will be the lucky ones.

Over the long run, it has become increasingly hard to beat the market—ironically because so many professional investors who now dominate the markets are so very capable! And it's even harder to determine in advance which fund managers will beat the market. That's why index funds that accept the collective judgment of the experts continue to outperform two-thirds of actively managed funds, and the one-third who appear to be winners in one period are not the same managers who outperform in the next period. Moreover, the underperformers fall short by twice as much as the winners outperform.

Critics often say that today's volatile markets demand active management and that management fees are low. Don't believe them. Fees charged by investment managers have increased substantially over the past 50 years—more than fourfold for both institutional investors and individual investors. Yet investment results have not improved.

If the upward trend of fees and the downward trend of prospects for beat-the-market performance wave a warning flag for investors—as they certainly should—objective reality should cause all investors who have been believing that investment management fees are low to reconsider. Seen in the right perspective, active management fees are not low. Fees are high—very high.

Of course, when stated as a percent of assets, fees do look low—a little over 1 percent of assets for individuals. But the investors already own those assets, so investment management fees should really be based on what the investors are getting in the returns managers can produce. Calculated correctly as a percentage of returns, fees no longer look “low.” Do the math. If overall stock returns average, say, 7 percent a year, then those same fees are not 1 percent. They are much higher—over 14 percent for individual investors in mutual funds.

But even this recalculation substantially understates the real cost of active beat-the-market investment management. Here's why: Broad-based index funds and exchange-traded funds that reliably produce the market rate of return—with no more than market risk—are now available with even lower fees than when the first edition of Elements was published. Today, market-matching returns are available to all investors at low “commodity” prices, such as 5 basis points (5/100 of 1 percent). Therefore, investors should consider the fees charged by active managers not as a percentage of total returns, but as the incremental fee for active management as a percentage of the incremental risk-adjusted returns above the market index.

Thus correctly stated, management fees are quite high. Leaving aside several interesting quibbles—such as that, for individual investors, taxes on short-term gains with 100 percent portfolio turnover can be significant—fees are remarkably high. Incremental fees are somewhere between 50 percent of incremental returns and, amazingly, infinity for the majority of fund managers who do not beat the market. And fees are generally closer to the high end than the low end of that range. Are fees for any other services of any kind at such a high proportion of value?

Fees are not “everything,” but just as surely, investment management fees are not almost “nothing.” And the one thing about investing we can be absolutely sure of is that the higher the fee paid to the purveyor of any investment product, the less there will be for the investor. Fees are far more important than many investors seem to realize. No wonder increasing numbers of individual and institutional investors are turning to indexed ETFs and index mutual funds—and those investors with experience with either or both are steadily increasing their use.

Of course, the mutual fund industry, which thrives on high-fee, actively managed funds, will always be trumpeting the benefits of switching into funds with the best recent “performance.” Often you will see advertisements that suggest that you will be better off switching into funds with four- or five-star Morningstar ratings, despite Morningstar's acknowledgment that its star ratings do not predict future performance and the reality that simply ranking funds by expense ratio provides a better predictor of future returns. In fact, Morningstar studied the behavior of mutual funds investors from 2000 through 2011 and found that investors lost billions through their return-chasing behavior. Had they simply bought and held a broad-based index fund, they would have improved their returns by almost two percentage points every year.

FINE-TUNING A BOND DIVERSIFICATION STRATEGY

In the first edition of Elements, we urged investors to diversify their equity investments by including asset classes in their portfolios that may be relatively uncorrelated with the stock market. Over the 2000s, bonds have been an excellent diversifier, providing stability to portfolio returns by performing particularly well when the stock market declined. But today, bond yields are extraordinarily low. We believe we are in an era now when many bond investors will likely experience very unsatisfactory investment results with many types of bonds. So investors who feel they need the steady income of bonds will have to think very carefully about how they structure their income-producing portfolios.

Unfortunately, we are very likely to be in an era of “financial repression” for some time to come, where savers who invest in ultra-safe fixed-income instruments will receive seriously inadequate returns. Many of the developed economies of the world are burdened with excessive debt. Governments around the world are having great difficulty reining in spending. The seemingly “less painful” policy response to the problem is a deliberate attempt to force savers to accept returns below the rate of inflation for a considerable period of time as the real burdens of debt are reduced. Such financial repression is a subtle form of debt restructuring and represents a type of invisible taxation. Today, the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond yields well under 2 percent, a rate below the headline rate of inflation. Even if inflation over the next decade averages only 2 percent, the rate of the informal Fed target, investors will find that they will have earned less than a zero real rate of return. And if inflation accelerates, the rate of current return to investors will be even more negative. Moreover, bond prices will fall, compounding the investor's losses.

We have seen this movie before. After World War II, America found itself with a debt/GDP ratio over 100 percent—close to today's level. The government's postwar policy response was to keep interest rates pegged at the low wartime levels for several years—10-Year Treasuries yielded 2½ percent during the late 1940s—and then allow them to rise gradually beginning in the early 1950s. Not only were interest rates artificially low at the start of the period, but bondholders suffered capital losses when interest rates were allowed to rise. Inflation reduced the debt/GDP ratio to about one-third in 1980, but at the expense of the bondholders, who suffered a double whammy during the period. As a result, even bondholders who held to maturity received nominal rates of return that were barely positive over the period, while real returns (after inflation) were significantly negative. As interest rates doubled, and then doubled again, bondholders suffered substantial capital losses. We are likely entering a similar period today with the result being a real harm to bond-holding investors.

So what is an investor—especially an investor in retirement who wants steady income—to do? Investors should consider two reasonable strategies. The first is to look for bonds with moderate credit risk, but with higher yields than U.S. Treasuries. The second is to consider substituting a portfolio of dividend-paying blue-chip stocks for a high-quality bond portfolio.

Whereas long-term U.S. Treasury bonds are likely to be sure losers for investors today, not all bonds should be considered bad like “four-letter words.” There are some classes of bonds where yield spreads over Treasuries are reasonably attractive. One category is tax-exempt municipal bonds. The fiscal problems of state and local governments are well known, and the parlous state of municipal budgets has led to very-high-yield spreads on all tax-exempt bonds. Many revenue bonds with stable and growing sources of revenue sell at quite attractive yields relative to U.S. Treasuries. For example, the New York/New Jersey Port Authority gets reliable revenues from airports, bridges, and tunnels to support its debt. Long-term Port Authority bonds yielded close to 5 percent in 2012, and they are free of both federal and state and local taxes in the states in which they operate. (High-yielding diversified portfolios of tax-exempt bonds are available through closed-end investment companies. While these funds employ moderate leverage, they provided yields around 6 percent. If tax rates increase in the future, they will become even more attractive as investments.)

Foreign bonds in countries that have much better fiscal balances than we have in the United States can be attractive today. An example would be Australia, where high-quality bond yields are in the high single digits. Australia has a low debt/GDP ratio (about 25 percent), a relatively young population, and abundant natural resources, making its future economic prospects bright. Its currency has been appreciating against the U.S. dollar. High-quality Australian bonds were available at yields of around 8 percent in early 2012. The same arguments can be made for Brazil and other emerging markets. Diversified portfolios of high-quality emerging market bonds are available in early 2012 at yields well above those in the United States.

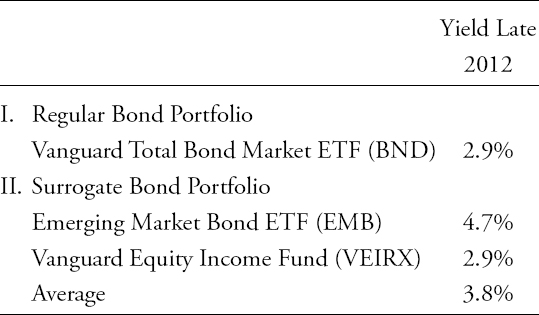

A second strategy would be to substitute a portfolio of blue-chip stocks with generous dividends for an equivalent high-quality U.S. bond portfolio. Many excellent U.S. common stocks have dividend yields that compare very favorably with the bonds issued by the same companies—and their dividends are likely to rise steadily in the future. One example would be AT&T. AT&T stock yields close to 5 percent—almost double the yield on 10-year AT&T bonds. And AT&T has raised its dividend at a compound annual growth rate of 5 percent for 35 years. Bond interest payments are fixed. If inflation accelerates, so should AT&T's earnings and dividends, making the stock perhaps even less risky than the bond. We believe income-seeking investors will be better off owning a portfolio of high-dividend-paying stocks than by holding a portfolio of bonds in the same companies. The following exhibit compares the yields available from a standard, diversified bond portfolio with a portfolio of dividend-paying stocks and emerging-market bonds, where interest rates are sufficiently high to compensate for expected inflation.

Surrogate Bond Portfolios in the Age of Financial Repression

Note that a broadly diversified “Total Bond Market” portfolio, available as the ETF ticker BND, yielded less than 3 percent as of the start of 2012. A surrogate portfolio made up of one-half broadly diversified emerging market bonds and one-half a fund of dividend-paying stocks yielded about 3.8 percent. And the dividend yield of the stock fund is likely to rise over time.

A FINAL THOUGHT

We can be certain that many more surprises will be in store for investors in the future and that our securities markets will remain volatile. The investors who will lose are those who chase after the current “hot” stock or the recently “best” mutual fund and then panic and sell out at times of adversity. The long-term winners will be those who control the one thing they can control—their investment costs—and have the fortitude to tolerate short-term volatility and stay the course in following a sensible long-run investment program.

Long-term investors will achieve the best results by capitalizing on the four best friends of the serious long-term investor:

- Diversification

- Rebalancing

- Dollar-cost averaging

- Indexing

Patience and persistence are the key factors for success in investing. The long-term investor who uses these tools and sticks with a sensible long-run investment program will have the best success.