If you want to shape the way an organization behaves, an extraordinarily robust conclusion from academic research is that the resource allocation process is key.1 Firms built to thrive under transient-advantage conditions handle resources differently from firms designed for exploitation. In an exploitation-oriented firm, reliable performance, scale, and replication of processes from one place to another make a lot of sense because you can operate more efficiently and gain the benefits of scale. Resources, therefore, are directed to support these goals, and changing these resource flows is painful and difficult. A transient-advantage-oriented firm, on the other hand, allocates resources to promote what I call deftness—the ability to reconfigure and change processes with a certain amount of ease, quickly.

In a typical firm, resources are controlled by powerful existing businesses, and the powerful people are those who dominated the last-generation competitive advantage. That means that new opportunities are often force-fit into an existing structure, if they survive at all. In a transient-advantage firm, resources are directed by a governance mechanism that is separate from any given business unit. Moreover, structures that suit the new opportunities are created. In a typical firm, every effort is made to squeeze as much operating margin out of existing assets as possible. In a transient-advantage firm, people realize that the competitive life of an asset may be different from its accounting life, and move to retire those that are no longer competitive before they desperately have to. Such firms realize that in contrast to the concept of “terminal value” from net present value (NPV)–oriented calculations, what one has instead is “asset debt”—the investment necessary to keep all assets at competitive best in class. In a typical firm, allocations of resources for growth (say) are handled with a capital budgeting mind-set, in which big black hole–type investments are made in the hopes of a huge payback. In a transient-advantage-oriented firm, instead, resources are managed with extreme parsimony, only being invested after a concept is proven. Finally, in a typical firm, ownership of assets is seen as critical because in the past owning assets created entry barriers. Firms adept at managing transient advantage recognize instead that today, access to assets, rather than ownership, provides flexibility and scalability without having to commit to a particular path and that the ready ability to access assets eliminates the advantage of actually owning them, in many cases. Table 4-1 sums up these differences.

TABLE 4-1

The new strategy playbook: resources and organization

| From | To |

| Resources held hostage in business units | Resources under a central governance mechanism |

| Squeezing opportunities into the existing structure | Organizing around opportunities |

| Attempts to extend the useful life of assets for as long as possible | Aggressive and proactive retirement of competitively obsolete assets |

| Terminal value | Asset debt |

| Capital budgeting mind-set | Real options mind-set—variable costs, flexible investments |

| Investment-intensive strategic initiatives | Parsimony, parsimony, parsimony |

| Ownership is key | Access is key |

| Build it yourself | Leverage external resources |

As I pointed out in chapters 2 and 3, a core implication of transient advantage is that what is good for a particular business may not be good for the organization as a whole. In a traditional company, people who had lots of assets and staff reporting to them were the important people in the company. This idea was reinforced by systems such as the Hay Group’s point allocation, in which more pay and power were assumed to go to those managers with bigger operations. Indeed, just recently I was chatting with the head of talent development for a major publishing firm, who believes that this way of rating people is their single biggest obstacle to becoming a more nimble competitor. The bigger-is-better mind-set is deadly in an environment in which advantages come and go. If people feel their authority, power base, and other rewards will be diminished if they move assets or people out of an existing advantage, they will fight tooth and nail to preserve the status quo.

Sony provides a clear cautionary tale. It yielded dominance in portable music to Apple. It ceded leadership in entire display technologies, such as plasma and LED, to other firms. It has no presence in many of today’s most exciting technologies, such as touchscreen computing devices. As an insider told me, “Sony was trapped by its own competitive advantages. They wanted to protect their technologies. When customers would ask [former CEO] Idei why the company didn’t make plasma or high definition televisions, he would say to them that Trinitron is superior technology.” Superior, no matter what the customers said they wanted. Indeed, as far back as 2003, observers were already pointing out the dangers of the “civil war” inside Sony, as no one mediated the difference in objectives between the content divisions and the hardware divisions of the company.2

Instead of allowing resources to be allocated at the level of individual businesses, a critical condition for competing in transient-advantage situations is to have a governance process for controlling resources that is not under the control of business unit leaders. Recall Sanjay Purohit at Infosys being asked to take resources back that were underemployed—remarkable! Wresting control from powerful people is not always easy, but it is absolutely essential if one is to avoid the organization’s interests being subsumed by what is good for an individual leader. In moving Wolters Kluwer from existing business models to digital ones, Nancy McKinstry used control over the capital allocation process as one of her key levers. Indeed, when I asked her what advice she would give to other CEOs faced with such a massive transformation in their business, she said, “My advice to other CEOs is to focus on capital allocation.”

Just as you need to reconfigure existing structures to go after new opportunities, so too you need to deal with the assets tied up with those existing structures. In many cases, they are still important to your organization, but they are no longer growth opportunities. The watchword here is to extract as many resources as you can from running these activities, because they no longer represent opportunity. Further, they can become obstacles to creating a deft organization because they tend to preserve processes that were designed to support a now-commoditizing business. Deconstructing reward systems, processes, legacy programs, structures, networks, and other elements used to deliver to an old advantage is not going to happen by accident and calls for real leadership. At IBM, for instance, stopping projects such as OS2 and exiting the PC business were both moves that freed up resources, time, and attention to be able to focus on opportunities.

The eroding differentiation of legacy assets can sneak up on you if you aren’t strategically alert. In past work, I’ve commented on the fact that what was once exciting and sexy about a product, service, or other offering that companies provide eventually becomes a commoditized nonnegotiable attribute.3 That means that customers expect something similar from all providers. The dilemma is that these things are often highly expensive table stakes. Not offering them to customers enrages them, but offering them, even offering them exceptionally well, does nothing for you competitively. Network reliability in your cable service, clean beds in hotel rooms, car ignitions that routinely start, restaurants that deliver what you ordered, accurate bills—all these things are hard to do. Because you have to do them but they don’t add to margin or gain you market share, the mantra for delivering them has to be to focus on cost savings. The slide from exciting to nonnegotiable means you need to change how you run the assets that deliver expensive nonnegotiable attributes.

This may be the time to bring in a rock-ribbed exploitation expert to wring every last bit of productivity out of existing assets. This is what happened at Apple when Steve Jobs returned to run the company in 1997 and astonished everybody by moving quickly to instill world-class operating capabilities in the areas of manufacturing, finance, and back office functions.4

There are a number of ways in which nondifferentiating activities can be made more economical. One is to centralize them under a shared-services model to end duplication of things being done in many places. Another is to create absolutely standardized processes rather than continue to support dozens of idiosyncratically designed ways of working. Remember, the activity or thing in question is not delivering a competitive advantage, so it really can’t justify being highly customized—it’s common in the industry. Simplification—such as eliminating handovers, automating portions, or making some of a process user generated—is a further source of cost savings. And of course outsourcing makes sense as well, particularly if the activity is not part of your competitive secret sauce. For instance, CAT Telecom and TOT Plc, two telecom operators in Thailand, plan to merge their wireless 3G networks.5 Running a network no longer offers competitive advantage, so why not share the costs of the nonnegotiable offer and compete on the basis of services? Giant telecom services provider Ericsson has capitalized on this idea, running networks for clients and offering technologies that it does not see as differentiating for itself.

Eventually, with most legacy assets, there comes a time when you have to make the decision to retire them altogether. To illustrate this process, let’s have a look at what Frank Modruson, the chief information officer (CIO) of consultancy Accenture, has done over a more than ten-year period of systematically replacing obsolete assets. Modruson doesn’t look like a revolutionary—he’s a calm, thoughtful guy who considers carefully what he’s about to say before he says it. But the change he led at Accenture’s IT organization was quietly revolutionary. As he describes it, the legacy systems in place in most organizations are like “concrete shoes,” the exact opposite of the deft structures that are needed to cope with transient advantages.

Like any other business asset, information systems depreciate. Over time, they eventually become competitively obsolete. The problem is that because vital corporate information resides in these systems, replacing and upgrading them is disruptive and expensive. Moreover, unlike physical assets such as plant and equipment, it can be hard to measure the point at which an IT system is no longer at a competitive standard. The consequence is that IT systems are typically repaired piecemeal, patched, and kept in use. CIOs often are not allocated the resources they need to replace, rather than patch, their systems. Although this doesn’t look dangerous in the near term, keeping legacy systems running is a major barrier to the reconfiguration that companies need to do to gain deftness, because legacy systems reinforce legacy structures and operations.

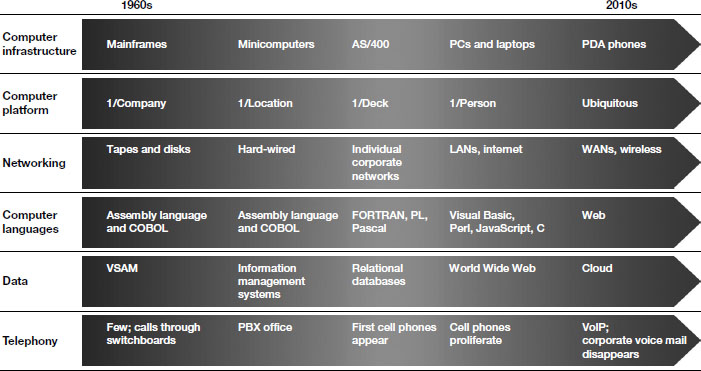

We’re talking at the moment about computer systems, but you can think about this logic for any class of legacy assets. Have a look at figure 4-1. It shows the decade-by-decade evolution of information technologies from the 1960s through the present. In the 1960s, there were mainframes, single computing platforms per company, and no linked networks (people shared information by sharing things such as tapes and disks); Assembly and COBOL were the favored languages; data was stored in Virtual Storage Access Memory files (an old IBM standard); and telephony actually used switchboards. Over the years, the problems these technologies addressed were increasingly solved by newer, cheaper, different ways of operating. So, for instance, today consumer technologies such as personal digital assistants (PDAs) and smartphones have taken over many computing chores that once required a mainframe to tackle. The same logic applies to changes in other technologies. Since 1980, new technologies such as radio frequency identification (RFID), LED and LCD lights, twenty-four-hour ATMs, DNA testing, magnetic resonance imaging machines, heart stents, genetically modified foods, and biofuels have all offered advantages over the technologies that came before, making previous solutions obsolete.

FIGURE 4-1

Evolving technology regimes in information technology

Source: Copyright © 2010 Accenture.

Here’s the problem: because upgrading legacy assets is expensive, there is a strong temptation among many firms to keep them running as long as possible. The result is often a bewildering patchwork of technologies that are inefficient, hard to change, and rigid. In the case of IT, it’s not unusual for a CIO to be simultaneously trying to figure out how to integrate iPhones, unified communications solutions, and cloud computing approaches at the same time he or she is praying that the company’s last remaining COBOL programmers don’t retire and take the secrets of how certain systems work with them. It is as if Milliken & Company (the textile producer we met in chapter 2) were to try to run its business of today with the equipment it operated in the 1960s!

The consequences of “patching, patching, patching” are predictable. The organization is left with a complicated IT infrastructure that is increasingly expensive to maintain and increasingly unresponsive to the needs of the business. Technology ceases to be an enabler and becomes an inhibitor. The concept is clear in IT, but relevant to other classes of assets as well.

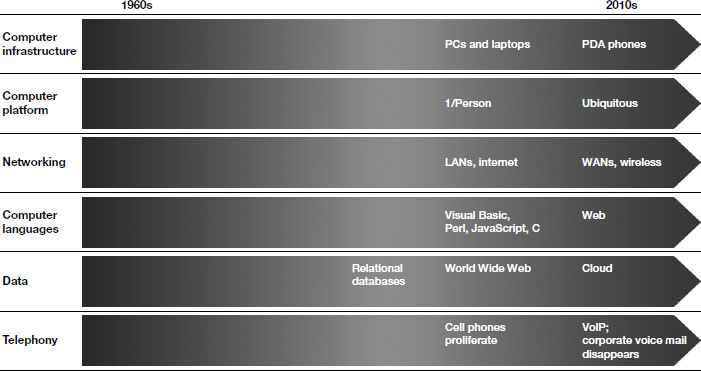

At Accenture, Modruson and then-CEO William (Bill) D. Green decided that if the organization aspired to excellence, it would need world-class IT infrastructure. This would require taking on the daunting task of proactively retiring older IT assets. Figure 4-2 shows what Accenture is working with today. Notice how the technologies of the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s have been left behind, and the company is instead focusing on having only more current assets in place. The guiding mantra Frank adopted was that anything implemented before 2000 should be eliminated. Ask yourself—if you were to make a similar chart for the assets, processes, and technologies in place in your organization, how much would it resemble figure 4-1? Figure 4-2?

Accenture’s IT journey began with the establishment of the company as a separate, publicly traded company in 2000. The company had 2,100 applications (600 global and 1,500 local). This resulted in, among other things, different views of the same data, because different systems produced different views of the same information. This created significant challenges for making timely and accurate decisions.

Modruson recently summarized the results of the company’s proactive retirement of legacy assets for me: “Today, the 600 global applications have been reduced to 247, and the 1,500 local applications have been replaced by only 242. The oldest application Accenture is still running dates from 1999, and it is slated for retirement in 2012.” But does all this proactive replacement of legacy assets really make a competitive difference? Absolutely. At Accenture, the percentage of revenue allocated to IT has been reduced to below industry standards, even as the company has more than tripled in size in terms of number of employees. Moreover, the company has enhanced its ability to move quickly because the newer systems are designed to support today’s strategy, not yesterday’s. That is a huge gain in deftness.

FIGURE 4-2

Leaving the past behind

Source: Copyright © 2010 Accenture.

I’ve mentioned before that it is often deadly for companies when resources are held hostage within business units. One needs to be able to wrestle control away from vested interests. At Accenture, the mechanism used was to establish an IT steering committee composed of the COOs and CEOs of the business units. Modruson established a ground rule that only the most senior people in each business unit could attend the meetings. At one point, a VP needed to beg off and asked if he could send a surrogate. “Nope,” said Modruson, “but you can send your boss, if he’ll come.” Astonishingly, the more-senior guy did show up to attend the meeting, offering a valuable senior-level perspective to the deliberations. As Modruson explained to me, any dilution of the importance of the senior-level steering committee would have crippled their ability to govern in the face of politics and demands from the businesses to get their individual needs met.

One of Modruson’s more difficult meetings took place when the IT steering committee decided not to fund a couple of his own boss’s pet projects. “What,” the senior guy said, “my projects fell below the cutoff? Isn’t there any way to get the funding for them restored?” “Sure,” said Frank. “If we allocate more funding, the projects that are below the line today might find themselves above it.” Eventually, the budget in that instance was increased, but not just for the boss’s pet project—for all the projects in the pipeline with that priority level. The integrity of the governance and alignment system was absolutely critical to Accenture’s ability to reallocate resources.

The “cutoff” rules were driven by a number of design principles specific to IT, but the process of making such decisions is applicable to any outdated asset. In the case of Accenture, the company valued consolidation, centralization, standardization, reducing the number of applications, and creating a single instance of any given piece of data. Just as we saw with Infosys in an earlier chapter, having one version of the truth allows for greater transparency, simplicity, and far fewer time-consuming negotiations about what is really going on. Getting work done becomes easier. As Modruson told me, “We don’t have those tedious and time-consuming conversations any more. There is one financial system for all of Accenture. One time and expense system. One HR system. What ends up happening is two wonderful things. The cost to run systems goes down because you have less of them. More importantly, the quality of the information goes up.” A major benefit for the IT group is that by giving all of Accenture’s people access to core information, each business unit can address its own information needs without turning to the IT staff, which helps it to be more productive and lessens the drain on the IT staff.

Contrast this with the experience of another multinational firm that I won’t name because it is just too embarrassing. Whenever the CEO had a meeting with another CEO, it took staffers up to four days to pull together information about all the company’s relationships with that firm. The data were hidden in various systems, spreadsheets, and even people’s heads. At Accenture, Modruson told me, this task would be a trivial exercise taking just minutes. Now consider the benefit to a firm like Accenture, and the commensurate disadvantage of the other firm in a context in which advantages are temporary.

Modruson coined the phrase “technology debt.” What this means is that keeping technology in a fit state to support a company’s competitiveness requires continual investment and a willingness to leave older assets behind. I would extend that more broadly to the concept of any asset that a firm might possess. Everybody knows that without maintenance, bridges, roads and tunnels, and other assets eventually break down. The important point is that the competitive life of an asset may be different (and usually shorter) than its accounting life. You can think of setting aside resources for investment in revitalizing your assets as an obligation similar to your company’s pension fund or other obligations. This thinking flies in the face of conventional NPV-based logic, however, in which even at the end of their useful lives assets are considered to have a terminal value. There is usually no such thing—instead, a company needs to be thinking of continually investing to refresh older assets.

Today, Accenture is continuing its pattern of investments. Major projects in the second half of the decade include applications rationalization, replacing the internal network, rationalizing its data center, and investing in data center virtualization. The network transformation program, for instance, let Accenture set up a cost-effective videoconferencing network. Aside from making collaboration far easier, it’s also had a positive second-order effect of diminishing the amount of travel its consultants need to engage in.

Just as shifting economic resources, such as budgets, is a key lever for increasing an organization’s level of deftness, so too is shifting power structures within the organization. We already saw, in chapter 2, how organizations such as Infosys proactively change their structures in order to unleash growth potential, arguing that allowing an existing structure to remain in place for too long creates inertia and results in an organization that is maladapted to the opportunities it finds. As Brad Anderson, former CEO of Best Buy, said in a session at the World Economic Forum meetings in 2009, “Organizations have habits. And they will cling to their habits at the expense sometimes of their own survival.” Breaking those habits often requires a structural solution.

One clear indicator that structure is getting in the way is when opportunities seem to fall between the cracks. I had first-hand experience observing this at DuPont, in a major project designed to, as former CEO Chad Holiday said, “get paid for what we know, what came to be called the ‘knowledge intensive growth program.’”6 DuPont historically relied on business models in which it gave away its knowledge in the form of consulting or advice in order to sell products. Holiday’s concept was that the firm should instead start getting paid for the value it created for customers, even if that value came from a service rather than a material. This was a sea-change for the two-hundred-year-old company.

At the time, DuPont was structured into strategic business units (SBUs), with each business unit leader responsible for that unit’s own assets, sales, marketing, and so on. The “aha” moment came when a team consisting of DuPont’s KIU director, Bob Cooper, and a few of us from academia, did an analysis of specific growth opportunities. Almost all of these fell outside the domain of any SBU. The SBU heads had little incentive to cooperate with one another or to promote new business models. To address this issue, DuPont had to massively reconfigure the company. The solution it hit on was to create what it called “growth platforms.” Each platform was given a specific broad domain that it could pursue, regardless of where the assets and people happened to be located within a particular business. Ellen Kullman was put in charge of the “Safety and Protection” platform, charged with going after unfamiliar business models that cut across former SBU territories. It was scary at first. “I spend a lot of time talking people off of ledges,” she told me at the time of the change. Her results were outstanding. From 2004 to 2008, the Safety and Protection Division posted record revenue gains of 64 percent and led to her appointment as the storied firm’s CEO.7

Established organizations tend to put far too much money behind new ideas, treating them as though they know exactly what will happen, even though they are highly uncertain. One of the unfortunate consequences is that when things don’t go as planned, there is an overwhelming tendency to persist, because the sunk costs look frightening to write off. This in turn often leads to painful and expensive flops, from massive product failures such as the Iridium project to disastrous acquisitions, such as the $850 million AOL basically wasted purchasing social networking site Bebo. A more effective approach in uncertain environments is to allow resources to be invested only when uncertainty is reduced, a core principle of options reasoning.

The companies led by entrepreneurs are often forced, by dint of simply not having a lot of resources, to operate in a lean, parsimonious way. To cite MacMillan, “They spend their imaginations before they spend money.” As a consequence, they gain deftness in the form of flexibility, few sunk costs, speed, and accelerated learning. This is consistent with the “options orientation” we discussed when we were looking at how the growth outliers get into and out of businesses. There are major lessons to be gained for resource allocation in large organizations from examining how they leverage their assets and resources. Two rich examples are TerraCycle and Under Armour.

TerraCycle got its start in 2001 when Tom Szaky and Jon Beyer, both Princeton freshmen, became interested in the role that composting might play in the then-emerging market for organic products. According to company lore, the actual inspiration was some Canadian friends’ success at using feces from red worms as fertilizer for a few home-grown marijuana plants.8 Szaky and Beyer conceived of a business that would use leftover food and other biodegradable waste as worm food, then use the worm excrement (to attract PR, they always refer to it as “worm poop”) to make high-quality organic fertilizer. They lost a business plan competition, but started the business anyway.

It was a classic low-budget start-up. They collected their raw material input in the form of biodegradable leftovers and empty bottles from Princeton University’s own dining halls. They scavenged furniture from students who left it behind at term’s end. Their initial investment in the business was about $20,000 for the conversion equipment, supplemented by angel investors. The business was set up in a down-at-the-heels part of Trenton, New Jersey. Initially, they reached out to green websites dedicated to the ecologically minded. Rather than use paid advertising, they developed an amazingly effective process for generating free publicity (which today they calculate to be worth about $52 million, including a National Geographic TV show, Garbage Moguls). Eventually the company expanded to offer its organic fertilizer to huge retailers such as Walmart and Home Depot. In 2007, a big incumbent firm, Scotts Miracle-Gro (a $2.7-billion-revenue company) decided that $1.4-million-revenue TerraCycle was a threat and slapped a 173-page lawsuit against the tiny company.9 The David-versus-Goliath struggle created a media free-for-all and put TerraCycle on the map. The lawsuit was eventually settled, but the publicity was priceless.10

In true options fashion, TerraCycle keeps its resource commitments fluid. As Szaky noted in a book he wrote about the business: “[I]t would have been impossible to predict or plan how to develop TerraCycle so that it would make it to the place it stands today. The trick was to be ever vigilant in seeking opportunities and to be ready to jump on them if they felt right inside and consistent with our core mission, even before they could be well thought out.”11 The company has stuck to its broad theme of supporting green business, but has extended its operations into a wide variety of additional arenas beyond fertilizer. Today, it is involved in so-called upscaling, in which by-products such as packaging are converted to new end products, as well as other green initiatives for large brand marketers. The company is rapidly expanding globally, with offices in far-flung places such as Brazil and a plan to become a billion-dollar enterprise in the green remediation space.

In a company geared toward transient advantage, the discipline of maintaining absolute resource parsimony is pervasive. The point is to keep investments to a rock-bottom minimum until cash-positive sales can be secured. Tom Szaky’s story of TerraCycle is an example. Another is the story of Under Armour, discussed in the next section.

Kevin Plank was a football player for the University of Maryland in the early 1990s. He is intense, with an athlete’s build and a bring-it-on-if-you-dare swagger. By the time I met him in person, in 2010, Under Armour, the clothing company he cofounded with fellow football player Jordan Lindgren, was generating close to a billion in revenue each year. The company has held its own in the face of fierce competition from the likes of Nike and Adidas, has over two thousand employees, and is continuing a pace of steady growth. And it is an outstanding example of remaining parsimonious in the use of resources.

The inspiration for Under Armour’s initial product came from Plank’s own athletic experience. The t-shirts athletes wore at the time were typically cotton, and during a rough practice they became soaked and, aside from being disgusting, started to get in the way. The tight, synthetic compression shorts he wore, meanwhile, stayed dry. He was inspired to find a way to make a t-shirt that would have the dryness, wicking, and comfort-enhancing properties of the synthetic shorts. Plank thus conceived of a new category of clothing, athletic performance wear, even though he didn’t invent the fabric (our friends at Milliken & Company actually did a lot of that).

The start-up was a model of parsimony. Plank spent much of 1996 in his Ford Explorer, visiting locker rooms throughout the Atlantic Coast Conference. He personally spent time with players, equipment managers, and others influential in selecting gear. His authenticity as a fellow football player and ability to articulate clearly why his products were superior created a powerful point of differentiation that was simultaneously easy to communicate. “We make athletes perform better” proclaims the company website, a claim that has not varied since his original inspiration.

Plank skillfully leveraged the loyal following among college football athletes to extend to pro athletes, eventually positioning the product with very visible and respected public figures. He proved skilled at getting inexpensive but high-impact attention. For instance, following his gift of samples, Oliver Stone’s movie Any Given Sunday featured Willie Beamen, played by Jamie Foxx, wearing an Under Armour jockstrap. The company successfully defined itself as the leading, disruptive player in the performance wear category. Today, Under Armour is a billion-dollar-plus business and maintains a strong hold on its category, although it is aware that things may change. The doors of the company’s product design area are overshadowed by a sign reading “We Have Not Yet Built Our Defining Product”—a symbol of a company that is keenly aware that advantages can be transient.12

A Meme on a Budget: Protect This House

As a Fast Company story reported in 2005,

[B]ecause [Plank] was thoroughly outmanned, he had to do more with less. He recruited dozens of college and pro players as his unofficial marketers. “Try it,” he told them, “and if you like it, give one to the guy with the locker next to you.”

For Under Armour’s first TV ad in 2003, the goal was to create a spot that would live longer than its 30 seconds on the air, says Steve Battista, director of marketing. The commercial showed a football squad huddled around Eric Ogbogu, one of Plank’s former teammates and a defensive end for the Dallas Cowboys. He shouted, “We must protect this house!” as if his life depended on it.

The reaction was a marketer’s dream—more than 50,000 calls and e-mails from athletes, coaches, even execs. Consumers sent in stories and tapes of themselves invoking the rallying cry at games, and even at sales meetings. Protect this house! banners appeared at NFL stadiums. ESPN anchor Stuart Scott and David Letterman quoted the phrase. It became shorthand for the brand, like “Just do it.”a

a. C. Salter, “Protect This House,” Fast Company, August 1, 2005.

At one time, asset intensity provided many businesses with the gift of creating entry barriers. When big investments were necessary to be competitive, it was hard for newcomers to become serious rivals. That situation has changed considerably in many industries. Say I were to give you the following challenge: create an organization that could compete head-to-head with any Fortune 500 company, without investing in any assets that you yourself owned. Thirty years ago, this would have been a preposterous proposition. Today, it is completely feasible. Increasingly, our world is one in which one pays for access to the assets one needs, rather than having to own them outright.

Consider my challenge—how would you meet it? The process would look a lot more like making a movie, running a political campaign, or staging the Olympics than the way most organizations operate today. You might contract with an innovation firm such as Innosight or Strategyn to help flesh out the business parameters and operating model. You might use a firm such as oDesk to get programming and technical work done. For jobs that require a human touch but which are easy to describe, you could use Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk” and pay by the task. Amazon can also provide you with massive amounts of computing capacity without your having to build a single server. Need specialized expertise? Guru.com has hundreds of highly qualified specialists on call in its network. InnoCentive can help you solve specific technical problems by giving you access to its network of “solvers.” You can get Regus to provide you with flexible, easily changed office space. Employees? Do you really need employees when firms such as Skills Hive or Adecco can provide you with skilled people in an on-demand way? The pace of competition sheds an entirely different perspective on how organizations and the resources tied to them relate.

The reason access, rather than ownership, is increasingly attractive is that it allows firms to adjust their structures and assets quickly as competitive dynamics unfold. Indeed, we are seeing increasing evidence of CEOs attempting to do exactly this in increasingly large swaths of our economy. The necessary resources are assembled to tackle a specific task or problem, and when the work is done the organization, such as it is, is disassembled and moves on to the next task. On-demand computing capacity, offered by organizations such as Amazon, “instant” factories available on the cheap for instant utilization, and technologies that can make anyone a skilled machinist or manufacturer are here today, ready to be accessed rather than owned. What we will see, increasingly, is a core of individuals who represent the long-term interests of the organization (its leaders and long-term staff) guiding the efforts of other people whose attachment is more episodic.

You can see the trend in the data on temporary employment. Employers are relying more on temporary workers rather than full-time workers, and this does not appear to be only a factor of the recession. The New York Times, citing Bureau of Labor statistics data, compared the percentage of new hires who were temporary workers across three different periods of recession (table 4-2).13

The temporary or “disposable” organizational form is all around us, and it fits well with strategies of rapid prototyping, quickly capitalizing on opportunities, and being willing to exit fast. In retailing, pop-up shops can mock up and test concepts without the commitment of a long-term lease. Even in manufacturing, processes that used to require casting techniques, precision tools, and years of experience to craft molds for devices can now be done quickly using digital files. An entire category of firms offering manufacturing-on-demand makes it possible to pilot and test new concepts for physical goods without the need for fixed plants and equipment. T-shirts from Threadless, manufactured goods from New Zealand–based Ponoko, self-published books from Lulu.com, and fashion design from Spreadshirt all allow small quantities of products to be created without fixed assets or significant up-front investment. Because their business model is often that no money exchanges hands until a customer actually buys a product, profitability can be built in right from the outset.

TABLE 4-2

Trends in temporary employment

| Period of economic recovery | Share of temporary as opposed to permanently employed workers hired |

| 1992–1993 | 11% |

| 2003–2004 | 7% |

| 2009–2010 | 26% |

In addition, large swaths of work that can be modularized and shipped overseas are being handled in just that way. Everything from reading radiology scans to scanning legal documents is work that is finding its way to cheaper locales as companies attempt to offload the human capital tied up in doing these tasks. And, of course, outsourcing of tasks such as running call centers, managing computer networks, and handling noncore tasks for organizations is a well-established trend. The key point is that you don’t need to own an asset yourself to benefit from its services. A related theme is to leverage external resources to the extent that you can, rather than trying to complete an ecosystem all by yourself. A disturbing open issue is that although increasing flexibility helps organizations cope with transient advantages, we haven’t yet come up with many humane ways of addressing the social adjustment problems this creates for people who were never trained to bear the burden of employment uncertainty themselves.

Is On-Demand Employment the Future of Work?

Mike Orchard, the founder of Skills Hive, wrote to me in response to a blog I wrote about the topic:

I founded www.Skills-Hive.com in the UK last year to help more people and businesses understand the potential of the emerging employment models. While I agree that many people currently prefer to put their trust in a single employer to provide their security for them, an increasing number are keen to spread the risk and make their own decisions on pensions and healthcare. The benefits are not just with the employer, clearly all parties gain better control and increased agility, which is the key to success in our fast moving world … Personally, I have to agree with a great phrase coined by a young British entrepreneur, Brad Burton … “Having a job is just like having a business, except you only have one client—and how stupid is that?!”

I also heard from Brad Murphy, one of the executives at Gear Stream, a company that does high-end technology design and development work. He wrote:

The nature of work is changing and many folks forget that the idea of a “job” is a relatively recent phenomenon that is an artifact of the master/slave model established during the industrial revolution. It is NOT the future of work (thank goodness). This current transition we’re now in globally will likely take another 50 years to play out, but on the other side are some very exciting economic outcomes. Brave visionaries will pave the way in the interim. I am hopeful we will be one of those companies that builds a brighter future by creating new business models that are respectful and sustainable for all stakeholders—Individuals, Business Owners/Shareholders, and the environment.

Despite these optimistic observations, however, it is clear that for many employees the concept of on-demand employment is highly problematic. The dark side of flexibility for employers is that it creates massive uncertainty for employees. In sectors such as retail, the New York Times reported massive changes:

“Over the past two decades, many major retailers went from a quotient of 70 to 80 percent full-time to at least 70 percent part-time across the industry,” said Burt P. Flickinger III, managing director of the Strategic Resource Group, a retail consulting firm. The consequence for employees is unpredictable working hours, fewer hours than they would like to work, and a loss of benefits and predictability. This wreaks havoc upon their ability to maintain stable family lives and plan their own time.a

a. S. Greenhouse, “A Part Time Life as Hours Shrink and Shift,” New York Times, October 27, 2012.

Sometimes a company can get the critical resources it needs by joining forces with another organization to scale quickly. We have already seen examples of this in the case of Procter & Gamble’s emphasis on “connect and develop,” in which the company sources innovative ideas, often from smaller firms, and then uses its heft and scale to ramp them up and bring them to market quickly. Consultancy Accenture is another company that builds alliances with a number of technology leaders and innovators. Combined with its own industry expertise and skills at scaling operations, Accenture has been able to achieve formidable growth. The company has also had success building up external capabilities.

One of the more impressive success stories is a joint venture the firm began in 2000 with Microsoft, called Avanade. In an unusual move for a technology services firm, Avanade was created to focus on services that were based on Microsoft technology. The joint venture was announced in 2000. By the next year, it was operating in ten countries—a true global start-up—and had captured 120 of its large target customers and awarded 150 projects. By 2010, 11,000 people worked at Avanade. In ten years, the company had completed thousands of projects for hundreds of customers and had $1 billion in sales.

For the assets a company does decide to invest in, we are likely to see far greater emphasis on making sure that they can be disassembled and reconfigured as things change. This implies that rather than optimizing your asset configuration for a particular opportunity, you are more likely to prefer assets that can be flexibly redeployed. It’s also important to watch out for getting stuck with assets that can create exit barriers later on. For instance, these might include factors that could force the company to reinvest capital assets, extensive interconnections and interdependencies with other businesses, substantial vertical integration, commitments to large numbers of stakeholders (such as unions or governments), codification of the business into written rules, or the potential for entrapment by customer demand later on (for instance, flood insurance or ATMs). As a general rule, in a transient-advantage context it is better to give up some optimization to create the advantage of flexibility.

The essence of this chapter has been to suggest that getting control of the resource allocation process is absolutely key to creating a deft organization that can cope with the effects of transient advantage. Having extracted resources from advantages that are fading away, it’s time to put them to work creating new advantages. That is the task of the innovation process, to which we will turn in the next chapter.