In far too many companies, the life of innovations resembles Thomas Hobbes’s despairing characterization of the human condition: “nasty, brutish, and short.” The fundamental problem is that in a world dominated by those pursuing exploitation, the innovation process is light amusement at best, a dangerous threat at worst. A broken innovation process guarantees that your organization will struggle to keep its edge as competitors catch up to whatever you were doing before. You should be thinking of how to avoid the cycle of success, decline, downsizing, near death, desperation, bet the company, and revival that characterizes so many corporate histories (such as Nokia, IBM, Procter & Gamble, and many others).

Innovation, like any other important organizational process such as quality management or safety, can be managed. Yet, for some reason when someone decides they want to become more innovative, they make it up as they go along, rather than learning what works and what doesn’t. So before you let people blunder around reinventing the process every time someone gets the urge to innovate, it makes sense to understand it first. Fortunately, there are a lot of resources that you can use to become better informed about what innovation requires, which can be put into action right away, avoiding the unfortunately common mistakes.1 The second thing to recognize is that on-again, off-again innovation, although very typical, is worse than doing nothing.2 It sends the signal to good people that these are not the kind of projects they should bet their careers on, and it wastes resources. So, if you want to get it right, innovation needs to be continuous, ongoing, and systematic. Set aside a regular budget for it. Make it part of good people’s career paths. Actively manage a portfolio in which innovations are balanced with support for the core business. And build it into the organizational processes that sustain anything else that is important in your company (see table 5-1).

TABLE 5-1

The new strategy playbook: innovation proficiency

| From | To |

| Innovation is episodic | Innovation is an ongoing, systematic process |

| Governance and budgeting done the same way across the business | Governance and budgeting for innovation separate from business as usual |

| Resources devoted primarily to exploitation | A balanced portfolio of initiatives that support the core, build new platforms, and invest in options |

| People work on innovation in addition to their day jobs | Resources dedicated to innovation activities |

| Failure to test assumptions; relatively little learning | Assumptions continually tested; learning informs major business decisions |

| Failures avoided and undiscussable | Intelligent failures encouraged |

| Planning orientation | Experimental orientation |

| Begin with our offerings and innovate to extend them to new areas | Begin with customers and innovate to help them get their jobs done |

In chapter 2, we had a look at the growth outliers—those unusual firms that have somehow managed to create proficiency at handling every aspect of the transient-advantage wave. What we saw in those firms is that they had built in ways of reconfiguring their businesses, by exiting exhausted opportunities and entering new ones, with the result that they combine stability and dynamism.

In researching these companies, it is clear that they have developed proficiency at managing each aspect of the innovation system, although they each do it a bit differently, of course. The core elements, however, are all there. This includes a governance system, and systems for ideation, for discovery and assumption testing, for market validation and incubation, and finally for commercialization and incorporation of the new businesses into their ongoing operations.

In many cases, efforts to become innovative are doomed from the start because there isn’t a clear overall framework within which innovation should occur. Roles are not clear, the governance and funding models are ill-specified, the specific activities of champions are left vague, and so on. In companies with an innovation proficiency, these matters are not left to chance. To be proficient, an organization needs a governance mechanism suitable for innovation (and usually separate from the planning and budgeting processes of the core business), a way of managing the resources devoted to innovation, an overall sense of how innovations fit into the larger portfolio, and a line of sight to initiatives in all different stages of development.

At Cognizant, one of the growth outliers, the overall framework is actually called the “managed innovation framework,” which spells out the different roles that are essential for innovations to occur. The company combines both top-down and bottom-up approaches to innovation, but makes it clear who is supposed to do what. As it says on its website, vision and enablement are steered by senior leadership. This includes laying out the strategy of the firm, specifying what types of innovation are desirable, and supplying resources. The so-called middle level in the organization owns and drives initiatives. This involves figuring out how to get new activities to work with existing ones, doing the political work of building coalitions and alliances, and making sure that desirable initiatives are appropriately resourced. At the level of a specific initiative, an entrepreneurial team does the work of creating new business transactions and driving them into the marketplace.

Cognizant supports this framework with a heavy-duty dose of technology. Ideas are tracked and communicated using its proprietary Innovation Management System software, which connects to its Cognizant 2.0 corporate knowledge management system. Innovation, in other words, is not treated separately from other significant tasks within the firm; rather it is connected to other ongoing activities in a holistic way. Similarly, Indra Sistemas has a system it calls the Indra method for development, adaptation, and services (MIDAS in Spanish), which integrates new projects with the overall project management process within the firm.

One of the most formal and structured of the governance systems for innovation amongst the outliers is that of the ACS Group’s environment business. It develops a strategic plan for what it calls R&D+i, meaning research, development, and innovation projects. It reviews plans annually or biannually, in a process that sets priorities and funding. Its formal management system is actually certified under the UNE 166002:2006 standard and audited by an independent third party. As ACS reports, as of December 31, 2011, there were twenty-eight research and development projects in progress, in which €5.62 million were invested.

The goal of the ideation process is to identify a pipeline of promising ideas that a company might consider as vectors for their innovation effort. It encompasses the processes of analyzing trends, connecting innovations to the corporate strategy, scoping potential market opportunities, and eventually defining arenas in which a company may want to participate. Effective innovation begins with a clear definition of where it should be focused. Unfortunately, in many companies, particularly those who have bought into the “let a thousand flowers bloom” concept, it isn’t clear what kinds of new ideas should be targeted.

Companies such as Google (and, historically, 3M) operationalize this theory by giving employees time at work to do whatever they want, without restriction or guidance. Everybody in the organization has the potential to be an innovator, we are told, and “no idea is a dumb idea.” Well-intentioned efforts of this kind usually begin with enthusiastic cheerleading at the executive level. People are told to dedicate a portion of their time to pursuits that interest them and that are not part of their day jobs. Trainers are brought in to teach everybody to be innovators. There are “innovation boot camps.” It works—ideas come pouring forth from every nook and cranny. Unfortunately, there is such a thing as a bad idea. Most won’t lead to large enough opportunities to merit the investment. Many are half-baked and impractical. Often, as Tony Ulwick of Strategyn notes, they are not connected to customer outcomes. Others are a poor strategic fit. Others will anger supply chain partners or important vendors. And so it goes. The ideas go nowhere. The effort eventually withers on the vine, the people who were most excited about the initiative get discouraged or cynical, and the lessons learned evaporate.

This is a lot like the old joke about an infinite number of monkeys: put enough monkeys in a roomful of typewriters and eventually they will produce War and Peace. The difficulty is that nobody has enough money or time for an infinite supply of monkeys, and in fast-moving competitive markets an inefficient innovation process could be your undoing.

Companies have discovered far greater power in an approach—variously called the “jobs to be done” perspective,3 “challenge-driven innovation,”4 or “needs-driven innovation”5—in which customer needs are inputs to a “growth factory,” as my colleague Scott Anthony argues.6 The core idea is that the starting point for innovation should be figuring out what outcome customers are really seeking and working backward into how your organization might make that outcome happen. Note the difference: unlike the ideas-first approach, in which thinking, often internally driven, generates innovation projects, the jobs-to-be-done perspective starts with what customers want to accomplish, but can’t get done. And of course, customers are notorious for being unable to articulate a need until they are shown how it can be met.

The growth outliers are specific about the kinds of ideas that fit their strategy. Infosys, for instance, is very focused on which types of clients it will serve and which it will not. The company focuses on high-growth industry segments and on the “reference” clients within them. It enjoys more than 97 percent repeat business, and has a philosophy that “our growth is a function of our client’s growth,” as Kris Gopalakrishnan explained to me. It refuses to pursue business (even though there are big volumes to be had) that doesn’t involve value-added for its clients in some meaningful way, rather than simply benefit from labor cost arbitrage.

Infosys then aligns the incentive structure of its people around these characteristics. Sanjay Purohit, its head of strategy, terms this “micro-segmenting.” He explains, “The goal is to improve the rate at which your business grows and how significant you are as a percentage of the whole company’s revenue. By micro-segmenting … it drives behavior across businesses of the need to create value, and become relevant to more customers.” Notice that identification of customer priorities comes first. A second “axis,” as Purohit terms it, is in the portfolio of products and services. Each year, he notes, Infosys incubates and lays out new lines of offerings with the explicit understanding that it will take three years to get significant growth. For example, the company has recently announced three new initiatives—sustainability, customer mobility, and cloud—with the understanding that they will be growth drivers in the future.

At ACS Group’s environmental business, the broad themes the company seeks to pursue are making maximum use of the energy that can be extracted from wastes, minimizing dumping, and reducing atmospheric emissions and odors. Krka seeks to use innovation to add value to its portfolio of off-patent drugs, increasing the value it offers to patients beyond the raw molecule rather than being a commodity producer of off-patent pharmaceuticals.

Note that the ideation process is never done once and finished—it needs to be an ongoing process of filling a pipeline of possibly good ideas. In our book The Entrepreneurial Mindset, we suggested the concept of an opportunity inventory, and that’s still an idea worth considering.7

With the seed of an idea in hand, the next process for proficient innovation is the process of discovery, in which concepts are fleshed out and detailed plans are developed. During the discovery process, specific customer needs are understood, arenas are sized and assessed for attractiveness, different business models are evaluated, and a rough framework for the business is created. In the detailed planning stage, assumptions are articulated and tested, a formal business plan and operational logistics may be developed, and key checkpoints are plotted out. The goal is to convert assumptions to knowledge as quickly and cheaply as possible. My previous coauthored book, Discovery-Driven Growth, offers a lot of detail on this process.8

If one examines the innovation process at Cognizant, one can see how the company has used technology to effectively support its discovery process. It has a system, called the idea management system, that allows the firm to track ideas and innovations, connect those who have knowledge that might be relevant to the innovation teams, test assumptions, and refine the ideas, all the while facilitating measurement and monitoring of what it calls “innovation scorecards.”

At FactSet, the discovery process is embedded in the company’s DNA. Its founders, Howard Wille and Charles Snyder, left their Wall Street jobs in 1978, as they later said, to “test their idea for a company that could deliver computer-based financial information.” Thirty-one years later, the company has boasted uninterrupted revenue growth. A series of case studies on the company’s website illustrates how it develops new offers by doing the discovery and detailed planning in close association with clients.

The incubation process of an innovation involves learning what the real business needs to be like. At this stage, pilots and prototypes are developed, market tests are conducted, and massive numbers of assumptions are tested. Initial customers and partners are engaged, and a dedicated team works exclusively on the project. The project is still vulnerable and fragile, but at this stage it begins to assume more substance as the prototypes become closer to a viable offer in the marketplace.

It is all too common for companies to rush through this phase, curtailing the valuable learning of what the ultimate product or service might look like. Another trap is to try to impose corporate demands for profits or growth on the fledgling business too quickly. Clayton Christensen said it best: “At this point in the development of an offer, one needs to be ‘hungry for profits but patient for growth.’”9 The offering is not yet ready for the full onslaught of commercial activity. Early adopters may put up with its inevitable deficiencies, but eventual mass market or mainstream customers will not. The best early markets are those customers who have a real, substantive need or problem that they will gratefully pay to have addressed. HDFC’s foray into offering banking to rural villages offers an example.

HDFC Bank has a long tradition of carefully piloting new initiatives before making a major commitment to them. Its recent partnership with Vodafone to introduce banking access to financially excluded rural Indians is illustrative. The bank started by understanding the problem it wished to address, which is that in many parts of rural India there is simply no banking infrastructure. Further, other infrastructure, such as transportation and electricity, is not well developed either. As a local paper observes, “A farmer in Jhalsu village loses a whole day’s earnings if he goes to a bank branch, a couple of km away, for a simple transaction like depositing or withdrawing cash.”10

What HDFC and Vodafone piloted in that isolated, rural village was a system in which HDFC Bank uses select Vodafone retailers to represent the bank as subagents, enabling anyone to send money or withdraw cash through Vodafone’s outlets. An HDFC Bank mobile bank account would allow the farmer to deposit cash that can then be withdrawn later or sent to another person, who in turn can go to a Vodafone outlet and collect the money. The service is much less expensive than prevailing alternatives, such as a money order processed via the post office. Having piloted the service in Jhalsu, leaders from HDFC Bank and Vodafone joined K. C. Chakrabarty, the deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India, to announce the national rollout of the concept under the umbrella idea of supporting financial inclusion. HDFC Bank anticipates significant growth from rural ventures such as this one.

A final step in the innovation process is when an idea actually gets to market and is scaled up to a commercial reality. This is a delicate moment for an innovation project, because it marks a major transition point. At this point, the innovation and incubation emphasis needs to transition to mechanisms for getting to scale, fast. The business that has been protected from conventional disciplines (such as producing return on investment) now has to begin to be measured by conventional metrics, reporting structures and disciplines need to be put in place, managers with a different mind-set start to become more important, and the business needs to become part of the parent corporation. Often, the governance of the concept has to transition from the group doing piloting and concept validation to a business manager, whose measures and performance metrics are more conventional. The key issue is to manage this transition without losing the differentiation of the business itself.

Commercialization and scale-up are particular strengths of Cognizant. Pursuing a strategy in which it has explicitly told investors that it will sacrifice some margin to sustain strong growth, it doubles down on investments made to create a compelling result in specific arenas it seeks to penetrate. Its CEO, Francisco D’Souza, was reported in 2009 to have said that he regretted that he didn’t invest in growth even more aggressively. As a reporter observed about the company’s approach to scaling up fast, “It meant putting more people on the ground; getting them to spend more time with a specific set of must-have customers, disproportionate to the revenue they might account for at that specific point of time; taking on projects which might not give high margins initially, but might eventually become big; investing more resources on a specific project compared to what peers do and so on. All these meant that Cognizant was constantly grabbing more market share.”11

How a Pure-Play Transient-Advantage Firm Manages Innovation

Introducing Sagentia

Cambridge-based Sagentia is a technical consultancy that to me exemplifies how companies can harness continual innovation to thrive, despite the coming and going of a particular competitive advantage. The lobby of Sagentia’s offices in hard-to-find-unless-you’re-local Harston Mill makes it quite clear that this is no run-of-the-mill suburban office complex. To your left is a glassed-in display area where what looks like the modern equivalents of medieval torture implements are displayed. Upon inspection, one learns that these are among the products Sagentia scientists and engineers have been instrumental in bringing into the world. All around you are colorful walls and soaring staircases, with windows onto flowering gardens. Although you have probably never heard of the company, its inventions are present in products that are today core to everyday life, in consumer as well as industrial products. One is led to a meeting room by a personal escort and politely asked to stay exactly where you are put, because what is going on around you is all top secret.

At Sagentia, innovation is clearly at the top of the agenda, throughout its operations. As one senior executive noted, “Inherently, companies like ours are super agile, because we are not in control of our own destiny … We can only live off something that our clients have decided to do.” This makes Sagentia a model for where more and more businesses are headed—as competitive advantages shorten and competition comes from everywhere, increasingly firms are in the same position, that is, “not in control of [their] own destiny.” Consistent, ongoing innovation and extraordinary closeness to customers is the only possible response.

The company has clearly identified sectors, or areas of interest in Sagentia-speak, and information gathering is confined to these areas, which fall under medical products, consumer products, and industrial products. As their joint managing director explained, “We use our sector organization to define our market agenda.” The sector organization provides a set of fairly fluid containers for the talents and capabilities in the organization. The sector heads, in turn, are deep experts on the concerns of potential clients in their sectors.

Sagentia’s leaders’ dedication to identifying meaningful customer needs is palpable. As Dan Edwards, a joint managing director, explained to me, “We are a projects (not a product) organization. We earn money when we understand our customers’ needs and impress them with our response. We are tested every day and put customer needs (not our assets) first in our thinking.” Identification of a market need comes first. For example, the company has been following a major trend in what it calls “life science meets lifestyle,” in which individuals are more and more going to be responsible for some or all of their health care services, often in a home-like setting. This trend will lead to entirely new categories of medical devices and treatment options, and Sagentia wants to be right there when the opportunities arise.

The amount of information the company’s executives sift through is staggering. Some 300 to 400 accounts of client meetings with salespeople and executives in the company are circulated each month. Senior executives, as part of their normal responsibilities, are expected to be very much on top of what is going on in their sectors. This includes reading trade journals, attending conferences, networking among key users, and “talking to people in a wide variety of scenarios.” The managing directors, similarly, spend significant time networking, leveraging the different vantage points they bring relative to the other executives. The company employs librarians who prepare e-mailed reports on companies, technologies, and trends that Sagentia consultants might need to know.

Niall Mottram, who works in the consumer sector, observes that the company uses qualitative techniques as much as quantitative ones for finding meaningful customer jobs to be done. “Take something simple like a domestic coffee maker,” he told me. “How people actually use that product can differ dramatically from how the designer envisaged it. People put in bottled water. They create their own flavorings. They double brew the coffee for extra strength.” The insights from in-the-field observations are captured by someone who knows a lot about human factors partnering with people who are more technologically oriented.

In addition to trying to understand particular customer needs, the company is good at seeing patterns that may cut across its businesses. Information gathered through its extensive probes into the outside world is organized into a central repository, which is sifted through by a dedicated person in marketing. This role—of cross-silo information gathering—is missing in many organizations. What the marketer is looking for in particular are trends that cut across Sagentia’s various operating areas. For example, a trend that the company is monitoring with “high-level pattern recognition” concerns personalization. Mottram offers personalization as a “macro trend” that Sagentia is expecting will influence the design of many of its future products. This applies even in services; as Mottram says, “People don’t want the same level of care that Joe Bloggs had half an hour before.” They want something individualized. Another macro trend is visualization, in which a surgeon might want to have both three-dimensional visualization within a procedure as well as a tactile feel in his or her fingertips, even when manipulating a robot or using a remote control.

Sagentia’s choice of projects exemplifies an approach to competition that is radically different from conventional companies. First, they work on new-to-the-world problems of great complexity. As one senior executive said to me, “ … we should be doing the stuff that is really hard to do, that is worth the money, which carries a premium of time or risk or technical complexity. Very few companies can do that. When we see lower level competition coming, that would be an early warning that it is not a good opportunity. It can be quite early in the life of that technology to the world, but it’s coming to an end for us.” Companies that escape the trap of established competitive advantage tend to have the capacity to create categories that are entirely new. Conventional concepts of competitive advantage have very little traction in such arenas.

Having decided a need is worth going after, Sagentia then mobilizes resources in a flexible, creative manner. According to Edwards, “All of our staff are operating in an internal free market—once a sector allocates a project, it has the pick of the staff from cross-functional groups (physics, electronics, mechanical engineering, chemistry, etc.). It’s very unlike a product company where, say, 90 percent of resources are allocated to legacy brands and/or products.”

The organizational structure changes as the projects the company works on change. This is vastly different from the way many companies are organized, and far friendlier to innovation. When I asked one of the sector heads for the most important advice he could give to other companies, he said, “You want to be mindful that you are not fulfilling your company’s structure needs. You are fulfilling the needs of the market. In many companies, company structure becomes more important than world demand.”

So far, we’ve explored the elements of innovation proficiency—managing the whole innovation process as a system, from governance through to scale-up and re-integration with the core business—and tried to understand how these processes are addressed in the growth outlier companies and Sagentia, a company that lives or dies by a constant flow of innovations. But by definition, the growth outliers are rare. Their success at getting innovations into the marketplace over time is, again by definition, unusual. So what about the rest of us—companies and organizations that don’t necessarily have proficiency already or that have a sneaking feeling they could do better?

Often, companies that want to become more innovative begin with a number of small-scale experiments with innovation and diversification. While there is no harm in experimenting this way, for these efforts to have a substantial impact on a large organization, the innovation effort would need to be given the same emphasis and attention as any other large-scale corporate undertaking. Here’s the problem: most people in large organizations are fully preoccupied with driving the core business. They’re already working long hours and grappling with crises on a day-to-day basis.

Moreover, what many companies don’t realize is that crucial aspects of the innovation system require real expertise that needs to be built up over years. Trend analysis, market sizing, options analysis and valuation, designing prototypes, creating discovery-driven plans, running pilots, leveraging opportunities, and making the transition to a scalable business are all activities that take time, effort, and experience to get good at. In most companies, there is simply no career path that consistently helps people to develop these skills.12 And in most companies, even if someone were to try to develop these skills, there are few rewards for doing so.

An obvious solution is to partner with organizations in which people spend their time doing nothing but living, breathing, and working on innovative ideas, in which there is spare capacity to implement the ideas you’ve come up with, and in which there is sound knowledge of what can go wrong and what to do when it does. Firms such as Innosight; IDEO; Accenture’s growth group, Strategyn; and Cameron Associates (a consultancy that my coauthor Ian MacMillan and I are part of) are all organizations that I’ve observed do great jobs helping their clients tackle situations in which the innovation process breaks down. If your goal is to build innovation proficiency quickly while making a minimum number of mistakes, it can really help to bring some expertise to bear on the effort. Let me walk you through what an engagement with such a firm might look like.

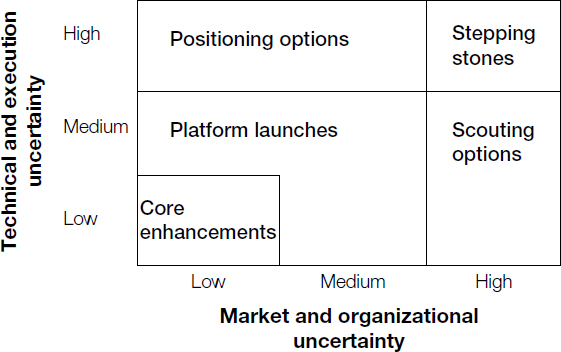

The first thing you need to do is get a baseline and figure out what is actually going on. One way to do this is to analyze your portfolio of initiatives. A model for doing this is explained in detail in my previous coauthored book Discovery-Driven Growth—I’ll briefly review it here.13 The first thing is to think of the world in terms of two kinds of uncertainty. The first is uncertainty about markets—both internal and external. The second is uncertainty about the capabilities or technologies that you might deploy in various projects. The model suggests that you allocate projects to five different categories (see figure 5-1).

Core enhancements are projects and initiatives that help today’s business better serve today’s customers. In the language of the model, market uncertainty and technological uncertainty are relatively low. Core enhancements allow you to become faster, better, cheaper, more productive, or more accurate or are easier to use and more convenient. The purpose of the core business is to generate enough revenue so that you can pursue your growth goals. If the core is not working well, that is job number one to fix.

FIGURE 5-1

An opportunity portfolio

Investments in new platforms, which generally have somewhat more uncertainty to them but are not bold leaps off into the wildly unknown, can be thought of as your next core business. These are generally projects that are in the scale-up stage of the innovation process. They represent future contributions to the core business.

The third category of investments is in options. Options are generally small investments you make today that buy you the right, but not the obligation, to make a more substantive investment in the future. Pilots, prototypes, early-stage experiments, living lab designs, and so on are all options. I like to think of options in three categories:

- Positioning options consist of initiatives in which you know there is a demand, but what is unknown is what combination of technologies and capabilities will be required to address that demand. Mobile devices such as smartphones in the United States are a bit like this—because there is no overall standard for wireless service, handset makers need to keep their options open by maintaining access to various types of standards.

- Scouting options are situations in which you have a capability or technology that you know how to use, and what you are trying to do is extend its reach into a new arena. That could be a new customer segment, a new geography, or a new application. Initiatives in this stage require a fair amount of prototyping and testing before you learn what will ultimately work. Apple, for example, built a mock-up of its retail store format and rigorously tested every aspect of the experience before rolling out its actual stores.

- Stepping stones are situations in which you think there will be a demand, and think the technology will eventually be good enough to address it, but the moment is pretty far off. The goal here is to begin commercializing with modest applications that solve a real problem but that aren’t too technologically challenging. The way nanotechnology is being developed today is a case in point—everybody knows that down the road nano manufacturing is going to produce marvels we can only dream of today. What is commercially available using nano-scale technology today? Wrinkle-free Docker’s pants. Cellphone screens that are fingerprint-resistant. All great, as they will lead step-by-step to an eventual commercial solution.

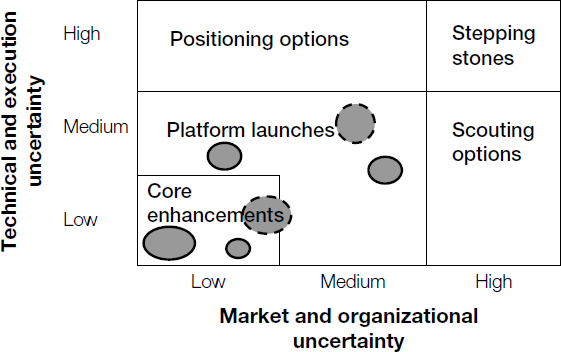

So the first thing to do is figure out what is really going on with your innovation program. Grab some sticky notes, make one for each project, lay them out by category, and see what you have. The first time you do this is typically a shock. What you will often find is that the project portfolio you actually have will not support the growth strategy you want. For instance, consider the portfolio in figure 5-2. A portfolio that looks like this is hardly likely to produce any more than low, incremental growth.

FIGURE 5-2

A low-growth portfolio

The goal here is to get a sense of what the growth gap is: Given where you think the core business will be in three to five years, what new sources of growth do you think your current portfolio will add? And accounting for declines in business that are being commoditized, what is the gap? That then becomes the target for your innovation system.

Astonishingly, even with evidence of a growth gap, it is entirely possible for senior leaders not to realize that the existing business cannot deliver tomorrow’s growth without innovation, as we’ve discussed in previous chapters. If an innovation system is going to work, however, the senior decision makers need to be on board. This can take a number of forms. What I often do is lead off with a series of presentations (one to two days’ worth) on the different disciplines that are necessary for innovation. The format is typically a series of lecturettes interspersed with discussion and sometimes application. If you’ve done your homework on defining the growth gap, that goes a long way toward supporting the argument that resources need to be allocated to building a growth system. It also helps if everyone has the same language for talking about innovative concepts. Leaders need to both make the commitment to innovation and establish the boundaries (we sometimes call it “creating the ballpark”) for where innovative efforts are to be directed.

I learned about the critical importance of getting senior-level buy-in up front the hard way, in working with Bob Cooper on the DuPont Knowledge Intensive University project I mentioned in the last chapter. We naively thought the shortage of ideas must be our major problem. So we enthusiastically delved into intensive brainstorming. Some of the ideas, we thought, were sheer genius. At that point, we went to the leadership group—the ones with the corporate checkbooks—to get the ideas funded. Thud. We had just made a profound mistake, which was not engaging the leadership from the beginning and not creating a strategic framework within which the ideas had to fit. The great new ideas were often not consistent with leadership’s priorities. No way were they putting money into this weird new stuff when they had important near term priorities to tackle. The ideas went nowhere. You can imagine how demoralized and dispirited the teams were—indeed, we had made things worse by creating excitement without following through. Since then, I recommend that any growth effort begin by establishing the leadership framework within which innovation needs to operate.

In terms of reinforcing mechanisms, I like to further insist that if innovation really is important to the organization, then it will show up in its meeting agendas, on its website, and other places where it is visible to the organization that this is something that really matters.

The next logical step is to organize the way in which innovations will be governed. The most common approach to doing this is to set up an innovation board, which is often a group of senior business leaders. The purpose of this board is to hear project proposals, ask the right guiding questions, give projects the green light, and, if necessary, help to shut them down in the most constructive way if they aren’t going to work out. The innovation board’s other major task is to clear away bureaucratic and structural hurdles that will hamper the efforts of innovation teams. A single phone call from a senior person can sometimes resolve problems that would take weeks to work out in a peer-to-peer context. At IBM, innovation governance was a mainstream responsibility with a senior person reporting to the CEO in charge.

As part of the innovation governance process, a definition of the opportunity spaces the organization is prepared to explore is developed. This provides clarity on what kinds of ideas are desirable (and which are not) and helps guide the innovation effort.

Just as with any other organizational process—say, six sigma—there are practices that work well when it comes to innovation and those that don’t. It is helpful to have a critical mass of people in the organization understand what some of those practices look like, even if they are not going to be responsible for doing the actual innovating. Training is usually the preferred vehicle to do this, and it can take many forms. I’ve done in-house classes, seminars, webinars, virtual training, you name it. The key thing is that you want people to begin to have a common language for talking about innovation and the recognition that what works for business-as-usual doesn’t work for innovation.

At Pearson, for example, the head of their clinical assessments business, Aurelio Prifitera, was concerned about renewing the business, even though it was, and is, very successful. In partnership with Krys Moskal, the vice president for people development, Prifitera initiated an effort to create a more systematic approach to innovation. We started with a day-long retreat with his leadership team to review basic innovation concepts. That meeting led to several initiatives: a portfolio analysis; the launch of an innovation board; allocation of resources to several new projects; and the funding of training and coaching to help people build up the skills needed for innovation. In the first year after that meeting, I led a series of fourteen teleseminars, running roughly two weeks apart, which could be attended by a broad mass of decision makers in the business (as Krys says brightly, “anybody has access to a phone, right?”). Some regular training such as that is crucial for developing skills and helping people create a common language.

At this point, it makes a lot of sense to pick one or more innovation ideas and begin to use the tools to develop those ideas. Often, this will involve a project that is already under way but struggling to get traction. The important thing is that the consultants or whoever you are using to support your effort have the chance to demonstrate proof of concept with something that is actually in the works. The practices of customer demand identification, market sizing, prototyping, business model design, discovery-driven planning, and all the other concepts that are specific to innovation come into play here.

What my colleagues Ron Pierantozzi and Alex van Putten of Cameron Associates learned—painfully—was that the way they thought they would be able to engage with an organization, after creating leadership buy-in, often didn’t work. They thought that once the leadership team had given the innovation effort approval and allocated resources to it, the next logical step would be to have a big meeting with all the project people to introduce them to the core ideas. Here’s the problem: by the time that meeting gets set up, months have often gone by. Just because people are now authorized to engage in innovation doesn’t mean their calendars instantly clear and their other commitments disappear. Instead, what Ron and Alex learned was that they did better working in bottom-up mode, selecting a few teams to support on an ongoing basis, and then helping them through the discovery and incubation phases of the projects, which is often where current staff lack the time and expertise to do this work.

Ideally, with early proof of concept that these techniques for innovation are useful, now is the time to start putting in place supporting structures. Dedicated teams to handle ideation, discovery, and incubation; IT systems (such as Cognizant’s innovation management system) that help link people together; budget structures that operate with a real options sensibility, and so on, are all part of creating a complete system. My colleagues at Innosight call this building a “growth factory.”14 At this stage, the venture is usually transferred to the structures that will scale the business and ensure reliability.

The steps themselves are pretty straightforward. What you need to be prepared for, of course, is that the established, exploitation-oriented organization will tend to resist them at just about every turn. My recommendation is that you plan on a two- to three-year effort to get your innovation system in place. Once you do, however, the benefits are tremendous.

To illustrate how the steps just discussed relate to a real organization, let’s have a look at a process that Ron Pierantozzi and Alex van Putten used to support the efforts of Robert Spencer, the chief innovation officer at Australia’s Brambles, over the past two years. Brambles runs a pretty unglamorous business, namely the circulation of pallets used to stock and move goods all over the world. Brambles was founded in 1875 by Walter Bramble, who was brought to Australia by his English parents when he was less than a year old. As an adult, he became a “cut up and deliver” butcher, meaning he would bring his products to customers. His company, subsequently called Bramble and Sons, increasingly concentrated on logistics, incorporating as a transport business in 1925 with the motto “Keep moving.”

The modern firm had its start in a historical accident. The Allied Materials Handling Standing Committee was created by the Australian government to provide efficient handling of defense supplies during World War II. When the Americans left Australia at the end of the war, they left behind mountains of materials handling equipment, among them pallets and containers. Managing these assets fell to an organization called the Commonwealth Handling Equipment Pool (CHEP), which was run for some time by the government. Eventually, the government decided to privatize the industry, and CHEP was sold to Brambles in 1958. The modern Brambles has a pool of more than 400 million pallets and other types of containers that it manages for customers in more than 50 countries. In the 2012 financial year, it generated revenues of $5.6 billion. (Yes, billion—on the basis of moving pallets and other storage containers all around the world.)

Our story starts in 2009, when Tom Gorman became the CEO, having joined Brambles in 2008 to run the CHEP operations in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa the prior year after a long career at Ford Motor Company. At the time, he told a reporter, “We are going to grow through geographic expansion, new platforms and new service offerings but now you need to put a real strategy around that. That’s what’s ahead of us.”15 He was determined not only to pursue innovation but also to make it a systematic, institutional capability as part of his legacy at Brambles. Not that the company wasn’t innovative already. As Rob Spencer, the company’s director of innovation, explained to me, “If you drop a powerful person in the company who was passionate about an idea, that person could make it happen.” What Gorman, who hired Spencer to drive the innovation effort, wanted to do instead was make innovation a systematic capability.

Gorman reached out to one of the world’s leading experts on growth, who had by then moved to Australia, consultant and author Mehrdad Baghai.16 Baghai suggested that Spencer work with Ron and Alex to create this systematic capability for innovation, which needed to be managed differently from the core business. They worked their way through the process I outlined in the previous section.

As Ron described the task at Brambles, “We start with trying to understand what they are trying to do. Companies will often say they want to be innovative, but you have to know what you are trying to accomplish.” Once you have a sense of the growth goals (which were quite ambitious at Brambles), then you think through how much you can expect to get from external sources, such as M&A or venture investments, and how much needs to come from organic growth.

With Gorman as an advocate, reasonably substantial funds were set aside to support the innovation process. These were corporate funds, not funds from individual businesses, to reduce the reluctance of business unit heads to be supportive. Another issue was to clarify what areas would be acceptable for innovation proposals. As Gorman had indicated at the outset, the scope for growth at Brambles would be focused on taking their intellectual property in pallet pooling and expanding that into new segments and geographies.

With an idea of how much growth they sought to get out of their innovation proposals, Gorman and Spencer set up an innovation board, which is an entity separate from business-as-usual governance structures.

There was some learning to be done, however. One problem the consultants ran into early on was that the CEO called the central fund an “innovation fund” and said the company was looking for more initiatives that had high uncertainty but that could also potentially have a big impact. As he observed later, “That language was just too restrictive,” and the company had people coming up with things that didn’t fit the criteria for being sufficiently innovative. He reflected later that “that caused some disillusionment.” The company actually had trouble getting enough good ideas into the pipeline at the outset.

So the company shifted from simply saying there was a fund to being more explicit about what the company was looking to do. It articulated three broad areas that would define what was in scope to be funded by the innovation fund. The first would include projects that were potential revenue generators. Then there were value generators, which were defined as projects that increase margins, help to maintain premiums, reduce costs, or just create greater marketplace differentiation. A final category was insight generators, the front-end piece that helps the company understand new and emerging customer needs. Then, the firm established targets for what would come out of the innovation fund. As Spencer says, “We expect to review at least X of each of these, fund Y, and graduate Z each year to grow.” To end the circular arguments about what was innovative and what was not, the company used five questions—if a project can answer “yes” on two of them, it is considered innovative enough to be a candidate for funding. The five questions are as follows:

- Does the proposal represent a new operating model or business model?

- Is it something that would open us up to new or different customers?

- Does the idea expose us to potentially new competition or different competition?

- Would it require new skill sets—do we need to recruit or train people to do it?

- Would it require new technologies or types of resources or facilities or whatever that we don’t know how to manage?

Today, there are similar boards to tackle more localized initiatives within the businesses, allowing for greater inclusiveness in the process and for more ideas to receive funding.

With their experience as practicing executives (in the case of Ron, as the director of innovation at Air Products and Chemicals, Inc., and in Alex’s case, as a financial whiz in three of his own companies and at Chrysler Capital Realty), Ron and Alex had had the job of creating innovation systems themselves. Since then, they have worked with a number of other organizations to do the same. The components they brought to Brambles included discovery-driven planning to build business cases and learning plans; opportunity-engineering to manage risk and account for option value; consumption chain analysis and attribute mapping to hone in on customer needs and opportunities; business model analysis to identify new business model opportunities; and many others.17 The advantage of bringing in people experienced in building these innovation systems is similar to bringing in experts for anything else new to the organization—it’s faster and less risky than trying to invent it all from scratch. (I’m writing about Ron and Alex because I’m familiar with their process, but there are other excellent consultancies for whom the same observations would apply.)

Among the benefits of working with people who have an external perspective are that they can help explain the financial side of innovation to people in the finance area; finance people have to be on board, philosophically. As a former finance executive, Alex can convincingly show how you can impose intelligent fiscal discipline on projects, even under high uncertainty, by employing options rationale and managing risks explicitly.

Another benefit of bringing in external expertise in building an innovation system is that you can acquire diverse points of view. At Brambles, Spencer was very keen to make sure that people’s ideas were challenged and that issues were examined from different perspectives.

Initially, Ron and Alex were brought to Brambles to give training sessions on the innovation system tools. Rather than providing empty classroom exercises, however, Rob and his team decided to start applying innovation tools to an actual initiative. At that time, one of their businesses had spent a fair amount of money on what it called “track and trace” technologies, but the project didn’t seem to be going anywhere. So it held a workshop, which Alex led, using the discovery-driven planning framework to work through the underlying logic of the program. As the teams worked through it, they came to the realization that what they had on their hands was a type of project that Alex, Ron, and I call the “living dead.” These are projects that haven’t quite failed, but haven’t succeeded, and which will simply absorb time and effort as they lumber on, with no real hope for a change in their trajectory. As Spencer said somewhat ruefully, “It would have been valuable if we’d had discovery-driven planning at the beginning of the process, before we’d spent the money.” It ended up being rational to wind it up and redirect the resources toward other endeavors.

The first year that Ron and Alex were involved, as I mentioned, was mainly devoted to training. They would do training for intact project teams in a variety of places, bringing in three to five teams at a time for two- to three-day workshops. In the workshops, they would walk through learn-to-apply consumption chain analysis, business model development, discovery-driven planning, opportunity-engineering, the use of sensitivity analysis, and so on. Despite everybody’s best intentions, however, the process wasn’t getting the traction that Rob Spencer would have liked to have seen. As Ron says now, “We’d go in and work with the project teams, but never heard a lot after the fact.” Actually, in my experience this isn’t unusual. It typically takes a while before a critical mass of people in the organization develops a common language and point of view about innovation.

In the second year, Brambles decided to change the model from a “training” emphasis to more of a coaching role. So Ron and Alex began to coach various project teams through key checkpoints, testing of assumptions and developing learning plans. Ron and Alex work with the innovation teams roughly on a quarterly basis, coaching them in how to test assumptions and how to think in a disciplined way about the projects. Ron told me the other day that “we just came back from a session in which we went through six projects—we ended up killing one, simply by doing the analysis and asking ‘why are you doing this?’” Among the things Ron and Alex are trying to embed in the organization is the idea of pursuing multiple options, thinking in terms of different scenarios, and differentiating behavior when one is working on innovation as opposed to business as usual. Instead of just doing training, the goal now is to create forcing mechanisms that keep the teams applying the skills, which are now being transferred to internal people to build the skill set in-house.

As I mentioned, Brambles funds the early-stage ventures from a central corporate pot, which makes the investment for the businesses less risky and makes them less reluctant to get involved. Once the new businesses start to generate revenues and profits, they pay back to the core fund. If the businesses are discontinued before they get to that stage, the businesses owe corporate nothing. Rob Spencer notes that this has an important psychological effect. Instead of people feeling that they might have career trouble if they are involved with a venture that is discontinued, they instead see that it can be used for learning and that there is little stigma attached. Further, there is very little downside risk for the associated business.

Today, the corporate innovation board meets monthly. There are now innovation boards within the operating business units, and Rob Spencer and his team have engaged in the same kind of consulting with them. Brambles now has eight dedicated people around the world working on innovation practices, in Europe, the Americas, and the Asia-Pacific area.

It’s worth noting a few things Brambles has done really well in developing its innovation capability. It hired and empowered a senior leader whose sole role is that of driving innovation, Rob Spencer. In all too many companies, innovation is either not a priority at all or, as Brambles previously found, is dependent on powerful people to aggressively champion an idea. Further, it set up a dedicated fund and governance mechanism to reduce the risk and potential for infighting among the business units. This also eliminates the chronic problem of new businesses being managed like more certain ones. Brambles also set up a measurement system to see how it is doing on implementation. As Ron says, “They track everything.” The company has what it calls an “innovation dashboard,” which tracks the following:

- Ideas submitted per month

- Sessions (workshops) held and on which topics

- Employees trained

- Ideas by category

- Status of the innovation fund in terms of total revenue opportunity

- Revenue opportunity by category

- Funds spent and returned to the innovation fund

- Opportunities received, opportunities funded, and opportunities launched

The value of a dashboard such as this is tremendous, both in keeping the innovation process tangible and fresh in people’s minds and in showing progress over time and letting people know symbolically that senior leaders are paying attention.

Brambles has also tackled the issue of incentives to engage in innovation. As I mentioned, the first thing it did was to remove disincentives by tackling the resource question and issues of fear of failure. To provide positive incentives, one of the mechanisms is that the most senior people in the company—the CEO, CFO, and business heads—all sit on the innovation board. The teams with ideas get to present to these very senior people, people who they might not have an opportunity to get to know in the course of their normal day jobs. So if their ideas work, there is huge visibility right to the top of the company.

Examples of innovations that Brambles is exploring include targeting ways to tackle the “last mile” problem in groceries and fast-moving consumer goods companies. A tremendous amount of labor cost in the supply chain is eaten up by human beings taking materials from storage areas and stocking shelves. Brambles is trying to find solutions that can limit the amount of handling that materials require. An example that is already in the market (particularly in Europe) is to sell fruit and vegetables in plastic crates. Those products would have been placed right into the crate when they were picked, then shipped in the crates and simply placed on the shelves. As Rob Spencer says, “That’s the kind of thing they’re looking for in other areas.” The company is also considering putting wheels on some pallets. The trouble is, as Rob notes, that retailers love the idea of wheels, and everybody else in the supply chain—logistics companies, manufacturers, producers—all hate them! So Brambles is considering whether it can come up with innovations that would give it the best of both worlds.

Although the journey at Brambles is ongoing (and has to date taken about two years), there are tremendous signs of progress. The pace of ideation has picked up, and the ideas themselves are less incremental. Rob Spencer has created an increasingly skillful internal group that can work with project teams to use the appropriate practices for highly uncertain ventures. It has also taken on training duties itself. As Ron says, “Rob and his team help people craft and develop the ideas.” Brambles’s annual report notes with pride that the company is well on its way to creating a culture of innovation, and innovation is featured as a key strategic thrust in the company’s 2011 annual report. Tom Gorman, in a recent TV interview, pointed with evident pride to Brambles’s “growth in every business.”18 If you can do it in pallets, you can do it with anything.

Innovation is not optional in a world of fleeting advantages. Innovation is not a sideline. Innovation is not a senior executive hobby or a passing fad. Innovation is a competency that needs to be professionally built and managed. Where in years past we often thought of strategy only with respect to existing advantages, in a transient-advantage economy innovation can’t be separated from effective strategy. Fortunately, we have a pretty good idea of the practices and procedures that allow you to do this successfully.

In this chapter, I’ve talked a bit about the importance of leadership to establishing the right processes for innovation. Effective leadership in a transient-advantage economy will also establish a different mind-set and approach than is appropriate to slower-moving spaces. In the next chapter, we’ll examine the different mind-set leaders need to adopt if they are to be successful in a transient-advantage context.