CHAPTER 6

Collaborative Operating Models

Joint ventures (JVs) were once the domain of international market entry—a necessary evil to comply with restrictions on foreign ownership. They also afforded access to local expertise and enabled companies to effectively “trial” foreign market entry with a smaller commitment of resources and a natural exit option in case the trial failed. But the nature of JVs has changed. A surge in collaborative deals has afforded access or scale in positional assets (e.g., resources, production facilities, etc.) and organizational capabilities and technologies. The nature of business opportunity has grown in complexity and uncertainty and now evolves at a greater pace, making it increasingly difficult to “go it alone.” JVs have also long been popular for large capital projects. State‐owned enterprises often collaborate in their quest for knowledge transfer and capability building. IOCs and NOCs collaborate with independents for access to attractive reserves. Oil and gas companies have turned to JVs as part of a broader strategy as their portfolios include more regions and resource types, including unconventionals, oil sands, coal bed methane, and more (Figure 6.1).

JV success is as much about creating an attractive opportunity as it is about finding an attractive opportunity. While resource assessment and partner attractiveness are important, the opportunity for value creation is equally dependent on deal design, design of the operating model, and implementation.

WHO USES JOINT VENTURES?

We have seen a surge in collaborative deals across many sectors and countries, with the primary impetus being to gain access to positional assets, technologies, and organizational capabilities.1 State‐owned enterprises often collaborate in their quest for knowledge transfer and capability building—for example, Saudi Aramco manages a large number of JVs with international oil companies, both domestically and overseas. Moreover, international oil companies and national oil companies have increasingly collaborated with independents for access to attractive reserves as well as to build capabilities (e.g., unconventionals). JVs are also a popular way to syndicate or share capital and risk in large projects.

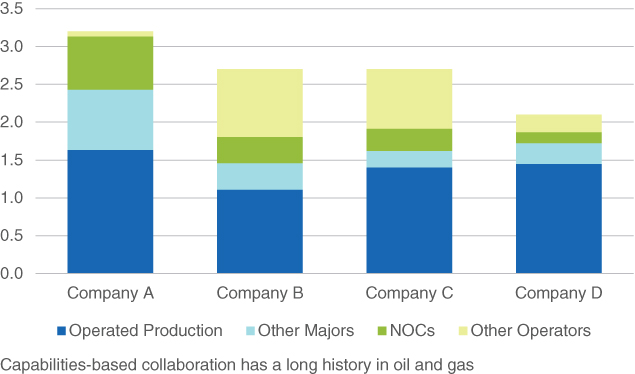

Figure 6.1 Portfolio Production by Operator (MM boe per day)

Source: IHS Energy

Access to Markets/Access to Capital

It is an oversimplification, of course, but TNK‐BP was an example of access to markets in exchange for access to capital. TNK‐BP was a leading Russian oil company and among the top 10 privately owned oil companies in the world in terms of crude production. It was vertically integrated (i.e., upstream and downstream) in Russia and the Ukraine. BP and the AAR consortium (Alfa Group, Access Industries, and Renova Group) each owned 50 percent of TNK‐BP. AAR was privately owned, mainly by oligarchs. The shareholders of TNK‐BP also owned close to 50 percent of Slavneft, another vertically integrated Russian oil company. Although financially successful, TNK‐BP has gone through political turmoil.

A Syndication of Capital

Again, it is an oversimplification, but KazakhstanCaspiShelf (KCS) was an example of a syndication of capital. KCS was established in 1993 to oversee oil and gas resource development in the Kazakhstan sector of the Caspian Sea. The government of Kazakhstan selected seven IOCs (Eni, BG Group, Mobil, Shell, Total, BP, and Statoil) to form the consortium. From 1993 to 1997, the consortium carried out a major seismic survey, identifying the Kashagan field. In 1997, the consortium and the government of Kazakhstan signed a production sharing agreement. In 1998, the government of Kazakhstan sold its participation to Phillips Petroleum and INPEX. A new joint operating company was formed, Offshore Kazakhstan International Operating Company (OKIOC). In 2001, Eni subsidiary, Agip Caspian Sea, was designated sole operator. In 2002, BP and Statoil sold their shares, and in 2005, all consortium companies, except INPEX, transferred 50 percent of the newly acquired shares to the Kazakhstan National Oil company, KazMunayGas. In 2006, Agip commissioned its first production well. In 2009, a new joint operator, the North Caspian Operating Company (NCOC), assumed the responsibilities of sole operator. Through Agip, agent for NCOC, Eni retained responsibility of the execution of the pilot program (phase 1). For phase 2, the co‐managers for project execution are Shell for offshore development, Eni for onshore plant, and ExxonMobil for drilling.

Economies of Scale

Infineum Holdings BV is a market leader in the manufacture of lubricant additives and operates as a JV between ExxonMobil Corporation and Royal Dutch Shell plc. Infineum has achieved great success in the market through a shared strategic agenda of its two shareholders, diligent execution, and economies of scale. In the 1990s, most majors had their own additives manufacturing business, creating special additives packages as a basis for fuels and lubricants production. Additive production became very unprofitable because of nonoptimized production and tremendous bargaining power by powerful lubes buyers who conducted annual tendering for large discounts. The consolidation of the sector, in part through the Infineum JV, has countered the buying power and increased the utilization of manufacturing assets. Infineum's primary competitor, Lubrizol, was taken private by Berkshire Hathaway in 2011.

A Syndication of Risk

Rosneft has partnered with BP and more recently ExxonMobil for the syndication of risk, for upstream development in the Arctic. However, the function of these partnerships have been undermined by the sanctions against Russia. In the BP share swap, BP acquired a 10 percent stake in Rosneft, while Rosneft took a 5 percent stake in BP. BP already had a 1 percent shareholding, bringing its total stake to 11 percent. The exploration agreement focused on the South Kara Sea and the formation of an Arctic technology center to develop innovative technologies for safe exploitation of the Russian Arctic shelf. ExxonMobil won access to the Arctic Laptev Sea fields, where Rosneft's prospective reserves amount to 36 billion barrels of oil equivalent. And with Rosneft 75 percent state owned, closer ties with the Russian government offered the potential for support in Russia. For Rosneft, the deals provided access to technical expertise, and potential for international collaboration elsewhere. Downstream, a refining JV offered the potential to tap a significant European customer base (i.e., in 2010, Rosneft had already secured a 50 percent stake, from PdVSA, in BP's Ruhr Oel).

Access to Capabilities and Positional Assets

Eni established a JV with Quicksilver with the hope of gaining access to organizational capabilities and positional assets (e.g., shale gas capability development and Barnett shale gas reserves). In May 2009, Quicksilver needed cash at a time when the capital markets were illiquid and gas prices were plummeting. It sold Eni a 27.5 percent share of leasehold interests in the Barnett shale for $280 million in cash, which represented only 5 percent of Quicksilver's total proved reserves. While not explicitly part of deal, Quicksilver saw this as a step toward expanding its unconventional footprint beyond the Barnett. Eni gained access to shale‐gas development at an established, low‐unit‐cost player, in a field that was more developed and understood than most unconventional gas plays. Eni was to “second team” with Quicksilver in Fort Worth—attend meetings, observe, share technologies, and so on—to help build organizational capabilities in land and lease management, field planning, directional drilling, well completions, process standardization, capital planning, upstream supply chain procurement and management, decision making, and decision rights. But in 2016, private‐equity‐backed BlueStone Natural Resources bought Quicksilver's US assets out of bankruptcy for only $245 million.

Other Joint Venture Trends

New technology is still an important lever for influence in setting up JVs—although many companies, including IOCs, are careful about technology transfer. Another key issue of focus has been securing the rights to market products from the JV. For example, Kuwaiti and Qatari companies continue to rely on Western partners for marketing and brand strength—IOC project management expertise is now a less important consideration. In both Asia and the Middle East, JVs are more common in chemicals than refining. But we expect to see NOCs rely less on IOCs and become more assertive partners. SABIC is more comfortable with 100 percent owned ventures, and while GE Plastics was a 100 percent acquisition, it will seek Western partners when entering some new business areas. SABIC is also increasingly more comfortable at marketing products and has built or acquired channels to market.

JOINT VENTURE STRATEGIC INTENT

The early cases of JVs were ones that provided access to international end markets for growth. This remains a popular (albeit declining) rationale for JVs, especially in consumer‐facing industries and markets with foreign ownership restrictions. The extent of globalism has now reduced the importance of this rationale (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Joint Venture Strategic Intent

Source: IHS Energy

The sharing, or syndication, of capital and/or risk is a second motive. This is especially true for capital‐constrained private companies, large‐scale projects in the resource, power, and infrastructure sectors, and smaller companies in the relatively risky technology and biopharma sectors. As we saw with the case of Infineum, JVs may confer the potentially significant advantages of relevant scale.2 But this does not simply mean an increase in size; coherence—the complexity, range, and related nature—is an equally significant factor in sustaining a competitive advantage. Together, size and coherence create the relevant scale that helps companies gain the depth and expertise they need if they are to deploy their assets and capabilities effectively. This insight may seem simple, but it represents a critical evolution beyond the conglomerate mindset of the past 40 years—a mindset that formerly focused on size alone, with insufficient emphasis on coherence.3

Continuous growth in advantaged positional assets and organizational capabilities has been linked to sustained growth and financial success. There are only three ways to develop the capabilities necessary for profitable growth:

- Build them organically.

- Buy them through M&A.

- Borrow them through virtual scale by using alliances and partnerships.

Successful businesses do not choose among building, buying, and borrowing—they conduct all three activities under one shared strategic agenda and a coordinated roadmap. Just as with M&A, or organic initiatives, JVs can provide access to advantaged positional assets and organizational capabilities. In fact, in some industries, the widening of bid–ask spreads in the aftermath of the capital markets crises has driven partnerships to become an increasingly popular entry approach. Many players continue to evaluate JV and other entry opportunities for US unconventionals as part of a broader unconventionals strategy initiative. While target attractiveness is important, the opportunity for value creation is equally dependent on deal design, design of the JV operating model, and implementation. We view the process as being as much about designing and developing an attractive opportunity as it is about identifying an attractive opportunity.

JOINT VENTURE VALUE AND VALUATION

An extensive body of research shows that JVs create value.4 Properly structured JVs confer many of the same benefits as an acquisition, with more flexibility. Significant wealth gains accompany JV announcements—the highest gains are in horizontal combinations in concentrated industries; gains are related to characteristics such as firm size, degree of relatedness of the JV with the parent, and the effect of a parent's JV capabilities.5

One analysis of 253 JV announcements found that companies earned positive abnormal returns around the announcement date, with three drivers of stock market reaction—strategic considerations, agency costs, and signaling:6

- The stock market reacted positively to JVs that involved a pooling of complementary resources, but

- JVs by companies with high levels of free cash flow were received negatively—those most susceptible to agency costs, and

- Small companies that entered JVs with larger companies earned significant positive abnormal returns, due to the signaling value.

JVs typically add value when two companies have complementary assets, creating an opportunity for operational synergies as well as sharing of risk, technology, and capital. On average, both parties gain—the more so with “marriages of equals” (unlike M&A). JVs often have more option value than M&A deals, by providing a firm with the flexibility to increase or decrease investment depending upon on how conditions develop:

- Commitment may increase as partners learn more.

- Commitment may be deferred through step‐up provisions.

- Commitment may be reversed by selling to the partner.

The strategic value of a JV and the flexibility that stems from a less than full commitment are important drivers of value.7

JV Costs and Challenges

Despite their prevalence, corporate experience with JVs has tended to be poor—some executives even refuse to consider them (see Figure 6.3). They are common but their structure leads to operational difficulties that impair both value creation and value capture. The complexity of JVs—evidenced by the number of key issues—makes them more difficult to execute successfully. JVs are especially difficult along many operational dimensions, which can impair both value creation and value capture. Moreover, in some cases, the incumbents are capturing the lion's share of any value creation.

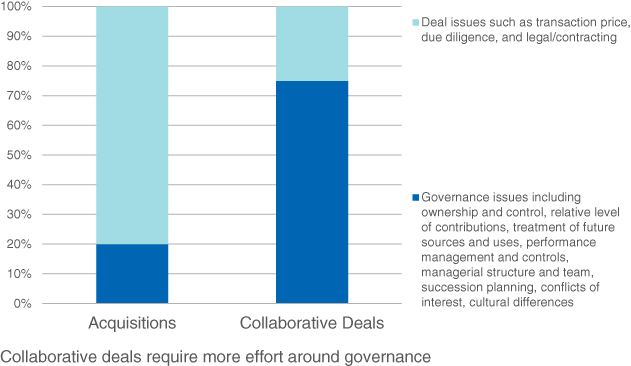

Figure 6.3 Comparison of M&A and JV Deal Effort

Source: IHS Energy

The forces of globalization had been putting the use of JVs into decline. Research on partial ownership of foreign affiliates by multinational companies has documented an overall decline in the use of JVs over the last 20 years.8 Companies have responded to regulatory and tax changes by using wholly owned affiliates instead of JVs and expanding intrafirm trade and technology transfer. Whole ownership is most common when firms coordinate integrated production activities across different locations, transfer technology, and benefit from worldwide tax planning. As much as one‐fifth to three‐fifths of the decline in the use of JVs by multinational firms is due to the increased importance of intrafirm transactions.

Other problems stem from an M&A‐oriented negotiation instead of a JV design process. It is typically the same people tasked with JV execution as with M&A execution—but JVs involve a very different set of issues that are more related to operating model design (see Figure 6.3). These differences dictate a more balanced and less competitive approach that sets the tone for a constructive relationship. Successful JVs are crafted with the aim of building trust and achieving a shared vision and understanding (versus a contract with explicit provisions for all possible contingencies), and strong incentives to seek business solutions instead of legal remedies. JVs tend to have finite lives and so we design structures with both a clear operating model and exit. It is difficult to ensure a mutual alignment of interests—different owners and the operators can each become significantly misaligned with respect to strategy, objectives, requirements, financial capacity, risk tolerance, and so on. The promotion and maintenance of trust and equity in the relationship is difficult due to the risk of value appropriation and differences in cultural, risk appetite, investment horizon, and financial resources.

DEAL STRUCTURE

There are many available variants in ownership structure, including wholly owned greenfield projects or acquisitions, JVs, minority interests, and public–private partnerships (see Table 6.1). However, deal design and ownership structure tend to be more of a means to an end than a stated goal in the blueprint design for a growth strategy or major capital project.

Table 6.1 Deal Structure Landscape

Illustration of deal structure alternatives

Source: IHS Energy

| Permanent |

Acquisitions (e.g., XOM‐XTO) |

|||||

| Long Term | Upstream supply chain services agreements; back‐office outsourcing | Drilling promotes, minority interests, equity cross‐holdings, private placements | Farm‐ins/farm‐outs, licensing, strategic alliances |

Joint ventures (e.g., CHK‐Statoil) |

||

| Annual or multiyear purchase agreements | Joint exploration agreements | |||||

| Transactional | Transactions (e.g., purchase order) | Seismic acquisition multi‐client studies | ||||

|

No Linkages |

Share Information |

Financial Holdings |

Share Control /Resources | Share Control /Ownership |

Wholly Owned |

Build, Borrow, or Buy?

Successful businesses conduct all three activities—building, borrowing, and buying—under one strategic agenda. Just as with M&A or organic initiatives, JVs provide access to advantaged positional assets and organizational capabilities. In Table 6.2, we outline some of the pros and cons and key considerations in a comparison of the major investment archetypes—strategic alliance (e.g., borrow), equity JV (e.g., borrow), control acquisition (e.g., buy), and greenfield subsidiary (e.g., build).

Table 6.2 Alternatives in Deal Design

Comparison of deal alternatives

Source: IHS Energy

| Strategic Alliance | Equity Joint Venture | Control Acquisition | Greenfield Subsidiary | |

| Structure | Contract between the parties | Jointly owned separate legal entity | Acquisition of control position | Organic build of wholly owned unit |

|

Market Entry |

Fastest Sharing of resources, positional assets, and organizational capabilities |

Faster Sharing of resources, positional assets, and organizational capabilities |

Faster Acquisition of positional assets and/or organizational capabilities |

Slower Build positional assets and organizational capabilities |

| Initial Outlay | Lower | Varies | Highest | High/moderate |

| Resources |

Lower May contribute technology, people, capital, or other assets |

Varies Either bring the deep pockets, positional assets, or the unique expertise |

Highest during integration Ongoing needs to be economically justified |

Higher Must hire expertise, source inputs; capital outlays for asset build |

|

Oper. Risk |

Higher More difficult to control counterparty |

Higher More difficult to control counterparty |

Moderate Integration issue |

Lower Dealing with employees |

|

Term. Risk |

Higher Difficult to transfer jointly developed assets out |

Higher Difficult to transfer jointly developed assets out Termination procedures expensive/consuming |

None The greater the integration the more difficult to unwind or dispose |

None |

| IP Risk |

Higher Dealing with a potential competitor |

Higher Dealing with a potential competitor |

Low Dealing with employees |

Low Dealing with employees |

| Net Present Value |

Varies Generally lower returns but on a lower investment |

Varies Execution risk may impair value creation Depends on how value is shared |

Varies Integration risk may impair value creation Depends on price paid |

Potential for higher returns on a more modest outlay Depends on importance of speed |

| Market Presence | Lower | Moderate | Higher | Higher |

For example, one study of multinational company (MNC) entry strategies in emerging markets found that they entered soon after the initiation of reforms, but limited their exposure to these markets, and the extent of technology transfer to the host country, until a much later date.9 In response to competitive pressures, companies increasingly use M&A and alliances to complement in‐house R&D efforts. Differences in the technological capabilities between companies determine the benefit from such deals. How partners organize alliance activities is also important.

One study of 463 R&D alliances in the telecommunications equipment industry found that alliances contributed more when technological diversity was moderate, rather than low or high. Some diversity is required to have something to gain from a partner; however, when too diverse, companies have difficulty leveraging each other. Structure did affect performance—through the incentives and ability to share information. For example, equity JVs improve benefits from alliances with high levels of technological diversity.10

Nonoperated Ventures or Operated by Others

Less common in most industries, passive minority interests, or nonoperated ventures (NOVs), remain relatively common in the production of oil and gas. The incidence of NOVs tends to mirror the regional strengths and weaknesses of the IOCs in different parts of the world—greater use in regions of the world where the company has less of an operational footprint, and less use in regions of the world where the company has more of an operational footprint. Recognizing the growing importance of NOV production and reserves in upstream oil and gas, super majors tend to have a separate NOV organization in some shape or form—it could be a separate global NOV organization or a corporate NOV group to “coordinate and share best practices.” In some cases, once an asset goes into production it moves out of the NOV group.

Public–Private Partnerships

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are a unique JV construct that involve a public institution alongside private enterprise, with equity contributed by both the private and public sectors. One important element in the case for PPP is the transfer of expertise from private partner to public entity.11 PPPs have helped to connect capital, resources, and expertise. The literature on private capital in public‐sector investments compares higher outlays on construction for the public sector with higher capital costs for the private sector.12 Research shows that the private sector is able to build infrastructure 15 to 30 percent cheaper than the public sector due to greater capabilities, more efficient project management, shorter construction time, and lower administrative expenses.13 However, in developed markets, the private sector cost of capital is 100 to 300 basis points higher than for the public sector.14 Nevertheless, the savings in development outlays offset the higher financing cost.15 Private participation in PPP projects depends on expected marketability, the technology required, and the degree of impurity of the goods or services. PPPs also tend to be more common in countries where governments suffer from heavy debt burdens, where aggregate demand and market size are large, and where there is previous case experience. Macroeconomic stability is also essential for PPPs, as is institutional quality—less corruption and effective rule of law is associated with more PPP projects.16

JOINT VENTURES IN PRACTICE—THE “HOW”

Many JVs (except NOVs) are separate entities, not operated by any of the JV owners. During operations, the biggest sources of influence are through the commitment of senior executives, members of the operating committee, or board. Parent company executives are borrowed and placed in senior management roles in the JV. For example, large IOCs (e.g., ExxonMobil) seek to impose their plant designs, operating standards, and procedures (often welcomed by SOEs). Some owners dedicate a small team of technical experts to monitor the JV in order to protect their own interests, such as monitoring the company's rights within the details of the JV agreement and doing feedstock and product analysis to support the company's position. However, the most important time to influence a venture is during its design.

Treatment of Sources and Uses of Cash Flow

We describe a typical ownership structure for a JV between two in‐market companies. The objective is to merge two region‐specific business units of each parent company in order to achieve “virtual scale” in that market. There are two parent companies. The two respective business units (referred to as A and B) are focused on one (same) geography. Businesses A and B are each headquartered in different countries and have in‐market companies in multiple countries. The deal is structured as a 50/50 partnership, with both parent companies as the only shareholders. Each partner contributes its relevant physical assets, with cash injected to achieve equal shares. Nonrecourse debt is raised by the entity to reduce the requisite size of partner equity.17

Capital Contributions

One early step is to identify the contributions that each party will make to the venture—these may be both tangible and intangible and the parties will need to agree on their respective values. Contributions may be topped up with cash or other assets in order to achieve a target level of ownership (and thus, voting power) for each party.

Related issues include the following: foreign ownership restrictions; rules or restrictions on in‐kind contributions; minimum capital requirements; capitalization requirements; initial and ongoing valuation of contributions; new issuance, share repurchases; capital expenditures; initial and ongoing funding and financing; ownership versus share of profits versus voting power; preferred returns; distribution of profits and cash; and treatment of dividends.18

Equity Participation

Equity participation tends to be a function of what each party's role will be in the management and decision making of the venture, and what it can contribute into the venture. There are three ownership archetypes: (1) a 50/50 equity ownership split between the prospective party and its JV counterpart—which will imply 50–50 management control; (2) owning a majority equity interest with a stronger management role; and (3) owning a minority equity interest with a weaker management role.

Management Control

Management of a JV will typically consist of a board of directors (or similar body) that makes extraordinary decisions on behalf of the JV, as well as a management committee to oversee day‐to‐day business. While the level of management control held by a JV party will typically correspond to its level of equity ownership, it is possible for JV parties to establish a management structure in whatever form is most beneficial, even if the control allocation does not match equity ownership.

Ongoing Needs

If a JV is economically viable and sufficiently capitalized, it should be able to obtain nonrecourse funding (e.g., working capital, seasonal debt) and financing (e.g., permanent debt) to meet ongoing operational needs. However, lower‐cost funding and financing may be available on a recourse basis (e.g., parent guarantee) or from the JV shareholders themselves. If the parents are to provide additional contributions, this is best determined at the outset. Alternatively, the parents may prefer merely to backstop the debt of the JV. As a practical matter, loan guarantees do consume debt capacity and expose the stronger parent to the credit risk of its joint counterparties.

Profit Distribution

In addition to planning for the financing needs of the JV, the parties will address plans for profit and cash reinvestment and distribution. In addition to their investment horizon, risk profile, and outlook for the business, legal, tax, and accounting go into these decisions.

How to Create Real Options with Contract Rights

JVs have received considerable research attention; however, only recently has this included analysis of the clauses found in shareholder agreements related to major capital events. JV contracts that include explicit options are more likely to depart from 50–50 ownership because the protection options afforded to minorities make parties more willing to contemplate minority positions.19 Agreements may grant rights such as:

- The option to put a stake to partners, or to call partners' stakes, in part or in whole, at a strike price that is typically equal to “fair” value. Put options maintain the shares of the payoff when stakes must be altered in order to preclude ex post transfers from the company. Call options perform a similar role when the problem of ex post transfers is replaced by that of ex post investment.

- Tag‐along rights (or co‐sale agreements) allow the parties to demand of a trade buyer buying their partners' stakes the same treatment as received by their partners. Tag‐along rights deny the ability to increase share of the payoff by threatening to sell a stake to a buyer that would decrease the value of the company, or by precluding others in selling their stake to a buyer that will increase the value of the company.

- Drag‐along rights allow the parties to force their partners to join them in selling their stakes to a trade buyer in the case of a trade sale. Drag‐along rights deny the ability to increase share of the payoff by threatening to hold out on a value‐increasing trade sale.

- Demand rights (or registration rights) allow the parties to force their partners to agree to an IPO. Demand rights deny the ability to extort value by threatening to veto a value‐increasing IPO.

- Piggyback rights allow the parties to opt into an IPO in proportion to their stakes and deny the ability to increase share of the payoff by including a disproportionate fraction of shares in an IPO.

- Catch‐up clauses maintain the parties' claims to part of the payoff from a trade sale or an IPO when the parties have ceded their stakes to their partners following the partners' exercise of a call option and deny the holders of a call option the ability to use the option to increase their share of the gains from a trade sale.

Each clause can be viewed as an option. These options serve to maintain incentives to make investments by maintaining shares of the payoff when the initial stakes cannot be adjusted to offset the distortion of major capital events (transfers from the company, to sell the company to a trade buyer, or to take the company public in an IPO). In the absence of these clauses, renegotiation may be required around major capital events.

Exit and Termination

One unique and important feature of collaborative agreements is some form of disengagement procedure. Even in cases where they are not followed exactly, they do provide a useful context for the parties to negotiate a peaceful exit. Where the JV is to have a fixed duration or a specific and limited purpose, termination issues are typically resolved during the design phase. The average alliance lasts between 4 and 7 years, with few lasting more than 15 years.20 There are many reasons for disengagement, including planned finite life, change in control, change in leadership, or change in strategy of a partner, capital constraints or liquidity needs, changes in the opportunity, price environment, capital needs, risk profile, competitive environment, regulatory context, or expectations not met. The most common choices for an exit mechanism are the transfer of a share, sale of the entire company, and the dissolution of the company. There are numerous elements, but the primary elements of a disengagement procedure are as follows: planned horizon, mechanism for notice of intention to withdraw (e.g., prior to set‐up of operations, 30 days; after setup of operations, 6 months), bid mechanisms (e.g., put/call features, right of first refusal/right of last look, veto rights, mechanism for valuation at exit), rights of the exiting partner (e.g., withdraw resources, recover assets, access to jointly developed assets and intellectual property), and rights of remaining partner (e.g., compensation for costs associated with withdrawal, right to continue operations).

Transfer of Interests

Primary types of transfers include third‐party transfers, transfers to a JV party or to the JV vehicle itself, and withdrawal or exit. Related issues include: enforceability under local law, disputes, failure to perform, material breach, insolvency or change in control, financing, liabilities, and other capital structure considerations.21

Sale or Dissolution

If it is not possible for one JV party to purchase the other party's interests, then the next most common approach is to provide for a sale of the JV as a going concern.

Other Considerations

There are numerous potential termination provisions. For example, the parties might establish guidelines for their respective intellectual property, such as patents, trademarks, brands, and associated royalties, including that developed within the JV. It may also be appropriate for the parties to plan for a period of noncompetition after the termination of a JV. In addition, if one party exits while the JV continues to operate, the remaining party may wish to secure transition services from the exiting party to minimize business interruptions. If specific transition services are difficult to anticipate at the time of JV design, the parties may establish that a departing party will agree to provide mutually agreed transition services at the time of exit. JV agreements generally include a mechanism for dispute resolution—the parties will prefer issue resolution by senior management personnel, as most disputes concern business issues, not legal issues. Arbitration awards can be easier to enforce than foreign court judgments and so the parties may wish to provide for arbitration in the event that leadership is unable to resolve disputes.

Operating Model Complications

Due to the operational challenges of JVs, best practice dictates a broader emphasis on operating model design versus simply ownership structure. A robust JV operating model, and its associated operational excellence, will help to achieve the vehicle's strategic intent and can be a source of sustainable competitive advantage. A JV operating model must go beyond ownership structure to address all of the elements of an enterprise operating model, including governance (e.g., information and oversight), organizational design, management processes, decision rights, and culture:

- Governance. What information will be shared with the owners, at what frequency, and what will be the cadence and involvement of oversight? What are the authority levels for the new entity?

- Ownership structure. What is the ownership structure for the new entity? What are the mechanisms for dissolving or changing its capitalization? How is financial policy (e.g., financing, dividends, and buybacks) set?