CHAPTER 5

National Oil Company Considerations

Most Western countries abandoned the National Oil Company (NOC) model many years ago, but the rise of NOCs has shifted the balance of control over the world's hydrocarbon resources. In the 1970s, NOCs controlled less than 10 percent of the world's energy resources, but now control the majority of the world's reserves and production.1 This shift came in concert with increased access to capital, expertise, and technology, as NOCs built in‐house capabilities to enable them to operate increasingly independently. NOCs continue to seek to enhance their ability to contract and manage operations through oilfield services companies.2

This shift has fueled a major evolution in roles and strategies for all oil and gas companies—including NOCs, international oil companies, and independents. NOCs have seen their power and influence grow. Moreover, the demands on NOCs continue to evolve with changes in the global energy landscape—changes in demand, discovery of new sources, and national and geopolitical developments. As managers of their country's natural resources, NOCs increasingly own and manage their complete oil and gas value chain from upstream to downstream activities, but now they are also emerging as both potential partners and competitors in the international scene in search of upstream and downstream assets.3

While the rise of NOCs saw the balance of control over hydrocarbon resources shift in their favor, they each face an increasingly disparate range of political and economic factors, strategies, and performance.4 This has profound implications for each of their strategic priorities, requisite capabilities, and operating models.

NATIONAL OIL COMPANY CONTEXT

The backdrop for sovereign state and NOC challenges includes difficult global economic growth amidst a slow recovery in developed economies, major geopolitics and policy “mistakes,” and slowing growth in China.

Asia led absolute global growth in real terms. While emerging markets exhibited high levels of growth, their reliance on access to capital and financial markets liquidity is problematic, given the regulatory siege faced by the sector in an era of post‐financial‐crises politics. Emerging markets that depend on external financing became more vulnerable with the end of extreme monetary easing—evident in a lack of secondary market liquidity for sovereign debt and spikes in emerging market bond yields. While macroeconomic management has been sound, there have been too few structural reforms; the state still plays too large a role. Emerging markets need to compete harder for funds, even with stronger exports. And while US expansion was sparked by an energy boom, it continued to be restrained by government regulation, policy, and politics. In the Eurozone, structural reforms have been essential to improving long‐run competitiveness.

World markets continue to face risks of political violence (e.g., war, terrorism, and civil unrest) in the Middle East and Africa post–Arab Spring. Syria's civil war and Israel's issues create global tensions. Libya and Iraq must rebuild infrastructure amidst security and oil production disruptions. Egypt's and Iran's politics restrict economic growth and yet job creation is critical to MENA's regional stability. In the Sub‐Sahara, poverty is declining and foreign direct investment is rising; commodity exports drive growth aided by expanding domestic markets. However, poor infrastructure (especially power generation), political instability, and corruption continue to be very significant obstacles to development.

National Oil Company Competitive Landscape

Although the fate of NOCs has historically hinged on the price of oil, the landscape is changing amidst new potential largely outside their control, including ultra‐deep‐water, the arctic, and of course, unconventional sources such as shale gas, tight oil, coal bed methane, and the Canadian oil sands.5 Growth in non‐OPEC production created a shift in the axis of supply from the Middle East westward to the Americas. However, these generally represent higher‐cost sources and so—as discussed in Chapter 1—there is a fundamental change in the global hydrocarbon resource base:

- Production of existing fields is falling, with declining reserves‐to‐production ratios (RPRs), especially for IOCs.

- Depletion of conventional or easy‐to‐access oil reserves; there are fewer large easy‐to‐access reserves (i.e., “easy barrels”), and these are increasingly under direct NOC ownership and operation.

- Rise of increasingly diverse resources, including tight oil, shale gas, oil sands, international frontiers, arctic drilling, ultra‐deep‐water; complex “niche plays” with higher costs.

- Drive to exploit more from existing fields is greater than ever; enhanced recovery growth has always been significant, though difficult to measure, but perception is that mature field opportunities are vast.

- Simple but depleted (i.e., “type curve tails”) reserves are increasingly the domain of smaller independents.

- Renewables and other alternative supplies continue to represent long‐dated, “out‐of‐the‐money options” for energy supply portfolios.

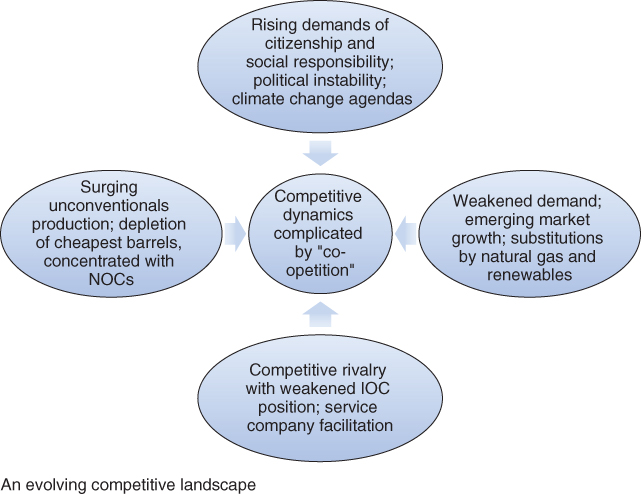

Competitive intensity on the supply side of the equation, with growth in unconventionals, has reshaped the competitive landscape, working against the forces of price control and the historical depletion of conventional supplies (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 National Oil Company Competitive Dynamics

Source: IHS Energy

In terms of exogenous challenges, there is moderate competitive intensity due to continued MENA region instability, the rising demands of their citizenship, and growing expectations for social responsibility. There is also growing concern about climate change and carbon. There are moderate challenges on the demand side—the global recession offset emerging market demand growth. Furthermore, concerns about climate and the environment, as well as price differentials, have driven growth in natural gas and renewables substitution for oil, coal, and even nuclear.

In terms of direct competition, NOC competitive dynamics are complicated by the need to both cooperate and compete with some of the same players. NOCs have needed IOCs because they were usually further up the learning curve and operate in diverse conditions, so they help with technology transfer. Emerging competition exists between IOCs and service companies with the host/NOC as the customer—competitive rivalry may grow as IOCs risk losing relevance, and service companies effectively enable this evolution. There is also growing cooperation and competition between NOCs themselves, as they increase their international presence and increase their level of vertical integration.

IOCs' significance and role in the oil markets has been in decline due to reduced access to low‐cost reserves. IOCs are focusing increasingly on more challenging and less profitable domains such as shale gas, tight oil, and deep‐water operations. Against a backdrop of declining oil production in existing fields and reduced access to low‐cost fields, reserve growth in restricted access or higher‐cost areas, integrated oil company profit margins have also suffered.6

Many of the resource‐laden NOCs enjoy advantages vis‐à‐vis the IOCs. Not only do they benefit from a tremendous endowment of natural resources, but they also are taking greater control. Growing in‐house capabilities—both assets and expertise—combined with increased direct engagement of service companies have made them much more self‐sufficient than in the past, as they increasingly test alternative owner‐operator models. In addition, financial resources are now a greater point of strength, as high oil prices and access to capital markets have given NOCs the financial wherewithal to bid for, and complete, major international projects and acquisitions.

NOCs benefit from an insulated base—they can tolerate international political risk better because their domestic business operations tend to be more insulated and less likely to be affected.7 NOCs benefit from political muscle and may be able to yield concessions that cannot be gained by IOCs, or are better able to mitigate overseas political risks through government‐to‐government relationships and negotiation strategies—they may be able to protect international assets through political or even military influence of their parent.8

IOCs tend to worry about Wall Street, the media, public opinion, and regulators, and be reluctant to invest in very long‐term prospects, or in unstable areas of the world (and must comply with international sanctions); NOCs merely need to ensure compatibility with national goals and policies, and are much less moved by concerns of Wall Street, regulators, or the media.

When it comes to challenges, NOCs face both similar and very different strategic and operational challenges. Many NOCs are especially prone to operational inefficiencies and governance problems. This is so prevalent that it has become known in the literature as “the resource curse.” Inefficiencies include poor management, unproductive labor, and staff bloating while governance problems include corruption, political influence, ineffective decision‐making, and “mission‐muddling” where the organization loses its way.

As NOCs grow larger and more diverse, (e.g., through international investment and vertical integration), they increasingly need to improve their management processes for financial risk management, portfolio management, procurement, contracting and risk sharing, and forecasting and cash management. And despite, or perhaps because of, numerous expat hires, talent management (i.e., attract, develop, retain) continues to be a major concern.

SOVEREIGN AND NATIONAL OIL COMPANY STRATEGIES

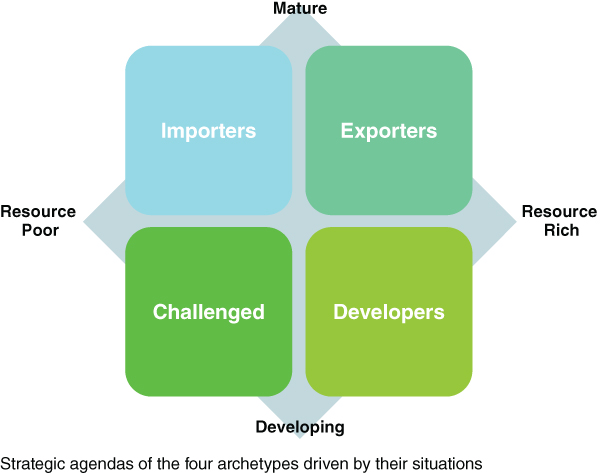

Sovereign and NOC strategies generally fall into one of four archetypes effectively driven by domestic resources and economic development (see Figure 5.2). These archetypes are importers, challenged, developers, and exporters.

Figure 5.2 Sovereign Energy Strategy by Archetype

Source: IHS Energy

Importers

Importers like China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea, have large, developed economies, but face shortages of domestic energy resources. Import‐oriented NOCs secure supply through supply agreements, production‐sharing agreements, or upstream investment, domestically or abroad, to offset their natural “short” position. The glut in supply and weak prices have led to more reliance on spot markets and spot pricing, rather than traditional long‐term fixed‐price supply agreements. Importers also invest in alternative energies and unconventional resources in order to develop domestic sources of energy production, and some have been investing to establish themselves as world leaders in renewables.

China—the world's largest oil importer—has invested overseas to secure supply and to hedge their natural “short” energy position. Chinese companies, including China National Offshore Oil Co (CNOOC) and Sinopec, invested more than $100 billion in recent years in international oil and gas assets. Acquisitions by China Investment Corp include: AES Corp., Cheniere LNG, CJSC Nobel Oil, GDF Suez E&P, Penn West, Ameren Energy ($825 million), Teesside Gas Processing ($225 million), Permian Basin pipelines ($200 million), Cockatoo Australia Coal ($150 million), Eagle Ford acreage ($130 million), and Canadian oil sands acreage.

China is also addressing the development of domestic (unconventional) resources with the release of a new Shale Gas Policy that underscores two objectives:

- Elevate the priority and stimulate the pace of shale gas development in China.

- Highlight the need for third‐party access to infrastructure in order to help China diversify its upstream sources and accelerate domestic development.

Japan has also been busy investing overseas, often with the support of the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC), which may provide equity participation and/or loan guarantees. Japanese companies (e.g., Tokyo Gas, Marubeni, Sumitomo, Sojitz, and Idemitsu) have invested in shale gas plays (e.g., Barnett, Eagle Ford, and Marcellus). Moreover, Chubu and Osaka Gas made an equity investment in the Freeport LNG project. Mitsubishi investments include Browse Australia LNG project ($2 billion), Montney gas acreage ($1.5 billion), German offshore wind ($500 million), and geothermal and solar.

Japan is also investing domestically in leading‐edge resource technology. For example, JOGMEC invested in the commercialization of methane hydrates production technology, with field trial pilots in both Japan and Alaska (see Table 5.1). Sustained flow testing was a key milestone in 2013 but it needed cost reduction and operational refinement in order to enter into commercial production. The pace of development will be slower than NA shale gas due to specialized offshore operations and higher capital.

Table 5.1 Methane Hydrate Pilots

Commercial development will be slower than the NA “shale gale”

Source: IHS Energy

| Ignik Sikumi (Onshore Alaska) | Nankai Trough (Offshore Japan) | |

| Date | March 2012 (30 days) | March 2013 (6 days) |

| Reservoir | Unconsolidated sand, 800 m depth | Unconsolidated sand, 300 m below seabed |

| Partners | JOGMEC, Phillips, US DOE | Japan Oil Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) |

| Production Mechanism | Molecular displacement (injected mixture of CO2 and N2) | Reservoir depressurization |

| Technology | Off‐the‐shelf tools and technologies—no specialized equipment | |

Now, it is all‐too‐easy for pundits to level criticism on actions that have been undertaken by some of the importers. With the benefit of 20–20 hindsight, “going long” at $100 per barrel certainly looks like a bad trade at $50 per barrel. But this needn't be indicative of a poor strategy. Buying a hedge always looks bad when the hedge goes “underwater” (i.e., out‐of‐the‐money), but we don't bemoan the purchase of home insurance when our house doesn't burn down. However, this can be indicative of poor execution; asymmetric hedges are a much better choice than symmetric hedges (please see Chapter 7 for more on sourcing and hedging) for those who wish to improve the difficult optics of an underwater hedge. Therefore, it is essential that Importers be clear and methodical in developing their objectives in a very premeditated way, with the involvement of all key stakeholders to ensure alignment on objectives and their criteria before developing the set of potential tactics. These tactics can then be objectively evaluated against these criteria, with some subset to be included in a blueprint for action.

For example, consider the general case where importer objectives might be as follows: (1) greater security of supply for energy and feedstock, (2) low/competitive cost of supply, (3) reduced price risk/uncertainty, (4) greater diversification of supply sources and with less sovereign risk, and (5) encourage domestic economic development and longer‐term domestic supply.

Let's also assume that Importers might consider a very broad range of potential tactics as follows: (1) long‐term physical supply agreements, (2) build physical storage and procure large spot and forward volumes on price weakness, (3) invest in non‐operated positions of upstream assets but with the provision of commercial offtake agreements, (4) acquire E&P companies with attractive upstream assets within economically viable shipping range, (5) invest in technologies that promote economically viable commercialization of renewables and other longer term domestic natural resources, (6) use swaps, forwards, and futures to manage commodity price risk, and (7) buy and hold shareholdings in major E&P companies.

Now, if we go through this list of tactics, we can fairly quickly narrow the field by noting that some choices fall very short on most of the objectives while others can be viable tools, pending effective execution.

Developers

Developers are those with developing economies and abundant domestic resources, but shortages of both talent and capital. Therefore, they often turn to public–private partnerships (PPPs) and long‐term production sharing agreements (PSAs) with beneficial fiscal terms and local content requirements—as sources of both talent and capital—to develop their domestic resources, build infrastructure, and encourage economic development.

For example, Ukraine signed a 50‐year $10 billion shale gas production sharing agreement with Chevron. And after the ruin of Iraq's oil sector by decades of conflict, the Iraq Central Government (ICG) tried to pass a national petroleum law (Oil Law) to provide a legal framework for much‐needed redevelopment, foreign investment, and expansion. The legality of the PSAs was ultimately accepted by stakeholders, authorizing IOCs to sign contracts directly with the ICG to develop specific areas of Iraq's petroleum sector, in exchange for a share of the oil profits (despite the lack of new petroleum law due to the protracted discussions between Iraq authorities and the KRG).9 We may see more PSAs in the future, not only for shale gas but also for other difficult resources such as methane hydrates or coal bed methane.

Beyond PSAs, there is also greater use of project finance and structured financings, often in conjunction with strategic or financial partners, to develop resources and make progress toward economic development. The inadequate infrastructure of emerging markets is in desperate need of expansion, putting a strain on available resources. The shortage of not only capital but also capabilities and talent makes public service infrastructure, and its entire supply chain, an important investment area that spans a wide spectrum of industry verticals. These represent significant growth markets with an attractive risk profile—the fundamentals can be compelling for those who bring to the table the requisite capital, capabilities, and talent.

Technology transfer is a critical issue for developers' oil and gas contracts because they hope to eventually control and operate in all aspects of their county's energy sector. Oil‐sector capabilities, including technology and expertise, are needed to ensure exploration efforts and production levels are adequate and consistent with national interests. Moreover, where the size of reserves is not sufficient to be economically attractive for the international oil companies, but perhaps for local consumption, domestic technology and expertise may be the only way to develop and use these resources.10

Under concession contracts, temporary imports of machinery, equipment, and skilled expatriate personnel have not provided much knowledge transfer. Even when there is technology transfer, there is a divergence of interests between developing petroleum countries and international oil companies. The development of local technological capability may not be in the interest of multinational corporations—it is a costly and time‐consuming process, and technology is a valuable and therefore limited good. Thus, technology transfer can reduce the value and importance of this currency.11

Exporters

Export‐oriented NOCs face the need to secure long‐term demand through sales contracts and downstream integration. They require investment capital and expertise to better monetize their domestic resources as well as to develop and diversify their economies. Exporters have mature economies and abundant resources, and are blessed with the luxury of strategic choice—choices about where to play internationally and where to compete along the value chain. They also focus on building talent and the adoption and development of world‐class operating model best practices—for example, management tools and processes, organizational design, decision rights, and governance. Beyond portfolio strategy and operating model, exporters also tend to focus on initiatives for operational excellence, operating efficiencies, and very‐long‐term competitive position.

About 10 percent of global crude oil is converted to high‐value petrochemicals and polymers where margins are higher than for refining and marketing. Furthermore, petrochemicals production supports national manufacturing strategies, adds value to national resources, creates jobs and diversifies their economy and provides import substitution. Exporters (and even some importers) have integrated into petrochemical production. NOCs, including CNPC and Sinopec (China), PDVSA (Venezuela), Pertamina (Indonesia), Petrobras (Brazil), Petronas (Malaysia), PTT (Thailand), Qatar Petroleum (Qatar), SABIC (Saudi Arabia), and YPF (Argentina) have built extensive, sometimes global, chemical businesses over the past several decades. Others, including Ecopetrol (Colombia) and YPFB (Bolivia), are more recent entrants to downstream markets.

BUSINESS MODEL IMPLICATIONS

Our changing resource base created ripple effects throughout the global economy with windows of opportunity in both public and private markets and at both the company and project level. It also affected optimal ownership, contracting, and production strategies for resource development.

Many NOCs, traditionally viewed as the custodians of their country's energy resources, generally owned and managed the complete oil and gas value chain. The role of the national oil company continues to evolve to reflect evolution in both supply and demand and national and geopolitical developments.

In terms of business model, NOCs vary in terms of (1) being monopolistic or playing in competitive markets, (2) degree of international participation, (3) involvement along the value chain, (4) whether they are asset operators or financial holding companies, and (5) whether they are net exporters or net importers.

The business models of IOCs and NOCs are diverging—the IOCs are increasingly withdrawing from the downstream and midstream, and choosing more focus within geographies or resource types, while many NOCs grow more international and more integrated. Increasing oil wealth brought about by rising oil prices encouraged governments as diverse as Bolivia, Ecuador, Russia, and Venezuela to confer greater political and economic advantage on their NOCs, achieved in local markets through revisions to constitutional laws, contracts, and tax and royalty structures. NOCs increased their power and influence in global oil markets. Co‐opetition between IOCs, NOCs and service companies afforded access to resources while contributing to the socioeconomic development of the countries in which they operate.12 NOCs are increasingly growing their downstream, and moving beyond their borders to invest in international frontiers and, in some cases, even unconventionals. Their strategic agendas are reflected in the following asset and capabilities building efforts:

- NOCs increasingly target international frontiers. India's Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Ltd. (ONGC), Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. (IOC), China's Sinopec, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), and Malaysia's Petronas have expanded in Africa and Iran, and are now pursuing investments throughout the Middle East. Russia's Lukoil is now an international player in the Middle East and Caspian Basin. NOCs are supported by home governments, and factor strategic and geopolitical goals into their investment and alliance decisions.

- NOCs are evolving from upstream producers into fully integrated energy and chemicals companies.

- Saudi Aramco, Petrobras, Petronas, and the Chinese NOCs all have in‐house R&D capabilities—PetroChina stands out as a top spender on R&D in absolute terms.13 Petrobras has expertise in deep offshore drilling, CNPC is reputed to be strong in enhanced oil recovery, and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) is experienced in heavy oil E&P. Saudi Aramco acquired Frac Tech International and opened an R&D center with Baker Hughes; NOCs increasingly engage directly with service companies.

In the face of these changes, the requisite capabilities to “win” are increasingly diverse. NOCs often turn to joint ventures and other collaborative deals for organizational capabilities and positional assets.14,15 NOCs have emerged as joint venture partners with the major oil companies, and increasingly as their competitors. Many NOCs are also more active in mergers and acquisitions, seeking international upstream and downstream targets. There are several NOCs with activities that go beyond domestic markets, engaging in strategic investment activities and acquiring full or partial control of foreign companies in sectors of strategic interest for national development.

Import‐oriented NOCs—most prominently China and India—are at the forefront of supply‐based foreign direct investment as their governments seek to prepare for long‐term energy supply challenges. These efforts (and Japan's) are hindered by the inadequacy of NOC corporate structures plus a lack of information and expertise, as well as the rise of economic nationalism and debates around economic sovereignty, security, and ownership of assets, and the perception in some countries that NOCs should not seek to acquire international assets.

Collaborative deals in the energy sector are used for access to positional assets, organizational capabilities, and technologies to gain scale or to syndicate risk and capital. The business model for NOC investment in petrochemicals frequently includes joint ventures or co‐investment with IOCs with petrochemical businesses of their own (BP, ExxonMobil, Total), or with pure play chemical companies (Sumitomo Chemical, Dow).

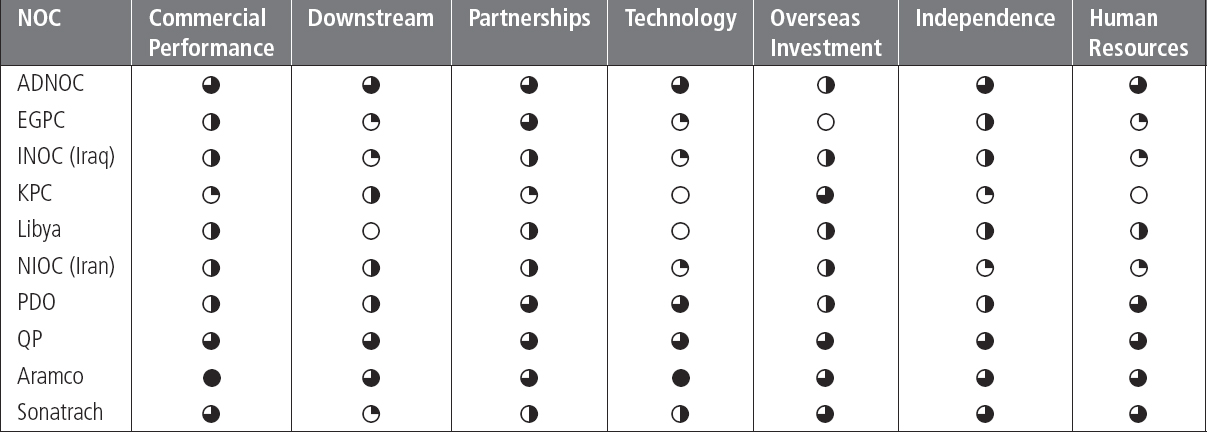

Growing NOC internal capabilities (both technology and skills), including growing project management capabilities, directly engaging service companies as contract‐operators, and increased capitalization, are leading to a situation where IOCs risk becoming less relevant to the NOCs (see Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Illustration of NOC Capabilities

Capabilities as strategic intent in NOC joint ventures

Source: Adapted from company websites

Importers

Importers will still require long‐term supply agreements for some portion of their total needs. However, they need to establish what level this is, as well as their optimal mix of fixed versus floating prices, from a risk‐return standpoint. In conjunction with this work, importers need to incorporate analysis of their basis risk for local delivery versus any reference pricing benchmarks, as well as counterparty risk (e.g., country or sovereign risk) for the source of supply.

Importers must marry these efforts with an active, real asset, investment portfolio strategy to enhance long‐term security of supply. Although international investments in upstream assets can provide an offset to hedge a short position (i.e., “equity hedge”), the physical oil needs a viable and potentially economic route home in order to avoid tremendous basis risk and to offer any true security of supply. Foreign sales of “equity oil” do not represent an effective hedge because these prices and their correlations vary significantly from the prices for domestically delivered crude, due to the wide ranging and volatile differences in netbacks.

The investment portfolio should also include domestic investment—renewables, unconventional resources, alternative energies, and other longer‐term sources to develop domestic sources of energy production. Additionally, the portfolio should include the “low‐hanging fruit” of conservation and efficiency improvement. In conjunction with these efforts, importers should also seek to establish themselves as the world leaders in renewables technology R&D.

Developers

Developers need to continue to employ public–private partnerships (PPPs) and long‐term production‐sharing agreements as sources of much needed talent and capital to develop their domestic resources, build infrastructure, and encourage economic development. However, to do this effectively, many developers need to conduct further study of optimal contract design—they need to do a much better job with the optimal design of fiscal terms and local content requirements, especially in today's price environment. For example, Brazil's onerous local content requirements have strained domestic resources and driven up capex to the extent that Dow/Mitsui canceled a sugar ethanol to polyethylene project (strength of currency was also a factor).

Developers must also employ a host of other tactics to build their domestic capabilities—including transfer, development of technical and management talent, and the build‐out of necessary infrastructure.

Financing these necessary tactics will be difficult—the big banks have been under regulatory siege and the capital markets are less receptive to sovereign risk. Project finance markets were scaled down and there is generally less liquidity in the secondary markets for non‐investment‐grade sovereign debt. Developers need innovative ways to monetize the value of their domestic resources at reasonable rates in order to finance domestic development.

Exporters

Thanks to their abundance of resources, developed infrastructure, and mature economies, exporters are blessed with the luxury of strategic choice. They must continually evaluate difficult decisions about if/where to play internationally, and where to compete along the value chain.

The business model for national oil company investment in petrochemicals frequently includes joint ventures or co‐investment with international oil companies that have petrochemical businesses of their own, or with pure‐play chemical companies. South Korean energy and chemical companies have been relatively slow to invest internationally, though in recent years, LG Chemical and SK (China) and Hanwha (United States) have diversified geographically.

Developers need to improve their long‐term competitive position through improved operating efficiencies and ultimately operational excellence. Therefore, they must do a better job of building management for both their technical and management ranks, and beyond talent, they require world‐class operating models.