CHAPTER 8

ADVANCED COACHING: COACHING AND DIVERSITY

Sheldon Daniel* and Anne Scoular

In Chapter 7, we discussed individual difference – the glorious way in which we humans vary, in all our myriad ways. This should be no different when we get to race, gender, ethnicity and all the other aspects of humanity that we think of when discussing ‘diversity’.

But it is different. For two reasons. First, these are groups of people who one way or another have suffered discrimination or adversity, so the playing field has not been level for them: compared with those who have not experienced overt oppression, they bring another dimension into coaching. And second, sensitive people (like coaches), get nervous around these topics. We are aware of the hazards and, concerned not to say the wrong thing, we may inhibit our ability to work well. This is partly because of the contemporary context, but it’s also because we didn’t hitherto have a codified approach to guide us as we enter that space.

Help is at hand. The most important part of this chapter introduces a new model designed to help coaches begin to frame their thinking on diversity coaching. It is so simple, powerful, and hence liberating, that I think it will become the equivalent of GROW for coaching around diversity. It is the Daniel Difference Model (DDM), and is the brainchild of experienced executive coach Sheldon Daniel who generously shares it below. The DDM will help you consider how ‘difference or sameness’ can impact your coaching relationship and offer some practical tips to ensure that you explore and moderate that impact.

But first, one caution: each human being has an utterly unique path through life. The group, and an individual within that group, are not the same. Some people, even if they seem to be a member of a habitually oppressed minority, may not themselves have experienced it first-hand – or internalised it as such. And of course, there are plenty of those ostensibly in dominant groups, who have suffered deeply. But there are many groups on this planet where some form of oppression has been so overwhelming, or sustained, or systemic, that one must at least take it into account when coaching an individual from that group, however unaffected they individually seem to be.

And of course, adversity can breed greatness, and resilience – the main problem may on some occasions be not in the coachee, but in the coach, who doesn’t know what to say. This is especially true when the differences represent situations where there is potential for traditional power hierarchies to be replicated within the coaching relationship (e.g. where a man is coaching a woman, or a white male is coaching a BAME client). Which brings us back to the DDM.

* Sheldon is a strategic communications expert and executive coach; see www.sheldondaniel.co.uk.

1. The Daniel Difference Model (DDM)

by Sheldon Daniel

Coaching for difference: shared bias v. shared assumptions

Coaches come from varied backgrounds and experiences. They bring that social identity to their coaching. While good coaching methods moderate the impact of their social being on the process and outcome of a coaching engagement, the coach and the coachee cannot ignore the fact that they exist within a prevailing set of (many times unconscious) cultural, organisational and societal assumptions. The model proposed below offers a framework for coaches to consider the manner in which the ‘degree of difference’ between themselves and their clients should be factored into the entire coaching process.

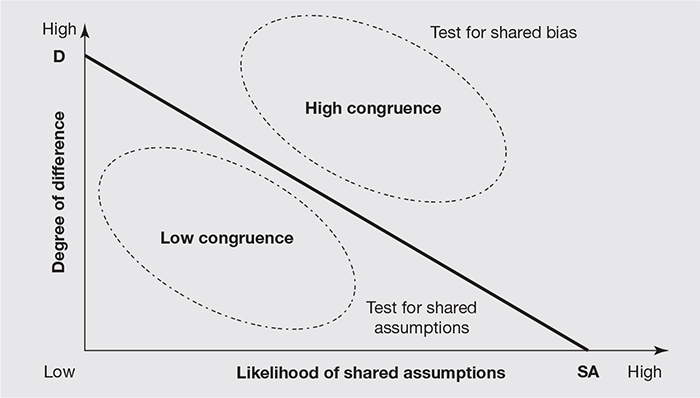

Specifically, we suggest that the coach and client may be in a condition of high congruence (where there is a limited to moderate degree of difference) or low congruence (a high measure of difference between the client and the coach). In areas of high congruence, the key risk will be shared bias – which might limit the range of solutions explored and the insights gained during the session. For low congruence situations, the main focus should be to test for shared assumptions – ensuring that even basic concepts/words are tested for meaning from the perspective of the client. (More on this below.)

Diversity is a pressing leadership issue – and companies are expected to have a response

The issues of gender and race are quite alive in the contemporary cultural and intellectual space. The reasons are debated but the rise of nativist political agendas on the backs of the ‘austerity backlash’ (e.g. Donald Trump, Brexit) across the globe, and ‘minority’ activist movements (e.g. #metoo, Black Lives Matter) have brought gender and race to the fore of the social and political debate. The role of women in business has a higher profile, as demonstrated by the recent demand for pay gap data at a firm level.1 For race, there is less visibility, but the gap is just as real. In UK FTSE 100 companies, around 12.5 per cent of the UK population are Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) – yet they hold just 6 per cent of top management positions.2 Ethnic diversity within the private and public sector in the UK and elsewhere remains a significant issue.

There is visibility to the problem although the solution is less clear. What is clear is it presents one of the most challenging leadership issues of modern business. Leaders are increasingly aware of it, but can be frustrated about how to relate to this agenda themselves, and progress it within their organisations. Even more important then for us to consider how it impacts our work, particularly with CEOs, executive management teams and boards.

Coaching is relational – social ‘difference’ can impact coaching

Specifically, we should ask how coaching is impacted by this broader discussion of ‘difference’. For the coaching purist, the immediate response may be that if the process of coaching is rigorously followed then this question has limited relevance. In this case, the client is considered supremely resourceful, and the coach assumed to be non-judgemental and non-directive – but still challenging and supportive – exhibiting curiosity through insightful questioning to help the client achieve clarity. There is little room for difference to ‘intrude’ in this formulation. Much of what has been discussed in this book so far will no doubt be aligned with that view and, as far as the process or the method of coaching is concerned, this is accurate.

However, Page and de Haan, in their broad survey of the state of research on coaching effectiveness, found that, ‘the strength of the coaching relationship or working alliance between client and coach is the most powerful predictor of coaching outcomes. Spending time building a strong relationship with a client is critical for successful and effective coaching, and it is perceived this way by both coach and client alike.’3

If the relational element is so essential, we then need to acknowledge the ‘social’ component of the coaching engagement. And hence, the extent to which – and how – social differences between the coach and the client might impact the coaching relationship.

The scope of a discussion on this issue is vast, so I will focus on how ‘difference’ impacts the process and relationship of coaching. Before proceeding, I would like to clarify the terminology of difference. Difference between a coach and client may refer to many dimensions. I am not referring to personality differences here since these have been subject to a considerable amount of research, and strategies for interaction across those types of differences have been fairly well articulated (e.g. for MBTI, as in the previous chapter). Gender, race, age, nationality, regional/national difference, culture, industry experience, sexuality, social background and physical abilities – we will assume (and it is a simplistic assumption) that the greater the number of these dimensions on which the coach and the client differ, then the greater the degree of difference between both.

‘Difference’ matters in our coaching because of our brain’s propensity to make predictions

So how does ‘difference’ get transmitted in the coaching relationship? I will use, as a theoretical basis, Dr Geoff Bird’s frame for understanding how, as humans, we relate to people.4 He highlights the propensity of our brain to make predictions quickly about what it will see, hear, think and feel. Because of this propensity, we mainly experience what we ‘expect the world to be’ (predictions) rather than conduct the costly (from a brain perspective) task of constantly undertaking the rational analysis of all the environmental information available to us in order to make sense of the world. We take a shortcut. However, while we regularly make these predictions (snap judgements), we are bad at doing it. However, we believe that we are good at predictions and, as a result, we tend not easily to see evidence to contradict our prediction.

These predictions are presumed to be shaped by our experience of the world as well as our ‘natural’ neurological predispositions. Lisa Feldman Barrett in her well received TED talk (one of the 25 most popular TED talks of 2018), makes a similar point as it relates to emotions. She noted that emotions are not universally expressed or recognised and (more relevant to our current discussion), the emotions we ‘read’ or detect from others are in part formed by or ‘built’ by our brain and our experiences. We take physical cues from others and then layer in an interpretation as we experience the emotion: ‘emotions are built not made’ says Barrett.5

If we are to agree with the work of both Bird and Barrett, then they are pointing to an important point in coaching – our experience plays a huge part in our interpretation. In fact, according to Bird, in coaching, the task is to work with the client to erode the confidence that they have in their predictions they make of the world.

And by this logic, coaches, or leaders when coaching, will also – like all humans – be making predictions of the motivations, reactions, emotions, intentions and even potential of the client – and this will be a function of their background. It is the predictions we make as coaches that make difference so important for the effectiveness of the coaching process.6

How the DDM works

The chart (Figure 8.1) below attempts to map the relationship between difference and the coaching process. Specifically, it suggests the nature of the algebraic relationship between the degree of difference (D) between the coach and client and the likelihood of shared assumptions (SA). In this relationship, the ‘line of shared perspective’ illustrates the inverse relationship between D and SA – the greater the difference, the less likely that there will be shared assumptions. Hence changed emphases are needed in both the process and relationship of coaching.

Figure 8.1 Coaching and difference: the line of shared perspective

Source: Copyright Sheldon Daniel 2019, All Rights Reserved.

The simple practical implication for coaching of the above abstraction is that the greater the difference between the coach and client, the less likely it is that the ‘predictions’ of the coach will be relevant – or will be similar to those made by the client.

If this is true, then there are implications for the coaching relationship. Specifically, the coach and client may be in a condition of high congruence – where there is a limited to moderate degree of difference and a fair to high level of shared assumptions. Alternatively, they could be in a state of low congruence – a situation in which there is a high measure of difference between the client and the coach and in which the level of shared assumptions is low.

In areas of high congruence, the key risk will be shared bias – and this needs to be constantly tested in the coaching engagement. For low congruence situations, the main focus should be to test for shared assumptions. Figure 8.2 demonstrates the areas of congruence as they relate to the ‘line of shared perspective’.

Figure 8.2 Areas of congruence

Source: Copyright Sheldon Daniel 2019, All Rights Reserved.

Using the DDM in action for coaching: a checklist using the Big Five approach

Such an analytical frame has practical implications for the coaching process. I have used the Big Five coaching skills as outlined in Chapter 5 as a basis for analysis. These are summarised in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Practical implications of difference on coaching using the Big Five

| Low congruence Test for shared assumptions | High congruence Test for shared bias | |

| Contracting |

|

|

| Listening |

|

|

| GROW Model |

|

|

| Questioning |

|

|

| Non-directive |

|

|

The above discussion is preliminary, and research on it is ongoing. However, if we agree that coaching is both a process and a social engagement, we need to begin to have a more data-rich conversation about the impact and the power of difference in the effectiveness of coaching. The frame discussed above is also a reminder that the heart of a coaching relationship revolves around two humans who – if they bring their full selves to the engagement – must be mindful of the strengths and foibles, assumptions and beliefs that they each bring. This will become even more pressing as the business environment is increasingly called upon to address issues such as gender and ethnic equality – and more general issues related to fairness. The coaching industry should have a critical review of the role ‘difference’ plays in the coaching process, and I hope the Daniel Difference Model (The DDM) provides a practical starting point.

2. Further resources

(Anne:)

I find the DDM very helpful, reminding me of the things to which I need to pay particular attention. With this trusty model at the core of our practice, there are then some specific resources available on coaching in the context of particular aspects of diversity.

First, gender.

As Sheldon notes above, gender inequality has been starkly shown in recent research on pay gaps. But there is much else. The pioneering work of Deborah Tannen showed that men and women, even from identical backgrounds, are assimilated into using different language forms (the DDM is relevant again!) – and those forms perceived as male then get disproportionately rewarded.7 In 2013 Herminia Ibarra and her co-authors listed a large number of barriers to women achieving parity in the workplace.8 Despite considerable efforts since then, recent research by Turban and others, using sensor technology, showed that the difference in promotion rates between men and women, in one company at least (but we suspect . . .) was due to bias, not difference in behaviour.9

There is a vast amount of other, equally disturbing research. As one of our wise alumni said to me recently, ‘The Code of Hammurabi listed women as chattels 3,000 years ago – this issue is deeply entrenched and won’t go away easily.’

What can we do about this, in our domain of business coaching? The starting point for me is an excellent guide by Bruce Peltier to coaching women. I confess when I first saw this, my hackles rose – I’m a woman I thought, we’re half the population of the entire planet, what can he possibly say of any relevance to coaching all of us? But within minutes, having read it, I was meek as a lamb. It is a chapter in his book The Psychology of Executive Coaching, and it really is good.10 He covers many of the things we have touched on above (Tannen’s work revealing language differences; cultural pressures; the stereotype v. the actual individual) but in much more depth than we can here. The old Gestalt saying, ‘simple awareness is often curative’ points to the initial step we can take in coaching women – just sharing the chapter with them (and possibly even more importantly, with men), will raise their awareness of what is going on around them. Individual reactions to this will then vary widely and become topics for coaching. And Peltier doesn’t make the frequent mistake of putting all the pressure to change on the woman; he outlines the vital steps organisations can and must do to change. There’s also a long list for further reading; altogether an excellent jumping-off point.

Let us turn to race.

(Sheldon:)

Perhaps one of the most difficult contemporary conversations centres on the issue of race, privilege and systemic marginalisation of groups based on ethnic grounds. The difficulty is based on uncertainty around parameters of acceptable discourse, complexity of the issue and legitimacy of speakers to engage. It is a valid concern.

As coaches we will face these difficulties – they are real. However, the guidance on this for coaching is limited, for a number of reasons, but it might be a result of a self-reinforcing loop. Fewer minorities at the top executive levels mean less of a ‘need’ for this to be addressed head-on by coaches, which in turn means it is less of an area of focus generally. The result is that it is not included in coaching with non-minority leaders – which just perpetuates the problem. If so, coaching, while not part of the problem per se, is not serving to help generate the questions that are relevant for current leaders.

It is important to realise here that the problem of race in the workplace is not self-evident. In fact, as Opie and Roberts (2017) note, ‘Workplace racism may be rendered invisible unless white employees choose to notice race.’11 So this points to one of the roles of coaching around the issue of race. This omission is a blind spot that needs to be named and raised, especially if the coaching revolves around issues of recruitment, management of a diverse workforce or even issues around strategy.

The other area of practical applicability for those who are seeking to break out of this loop (of course if you agree with the formulation), is that the issue of coaching for ethnicity/race should start with an understanding of the experience of work from the perspective of the minority coachee. This might sound simplistic but as Maura Cheeks points out in an HBR article, African American women state that they feel they have to alter their self when they enter the corporate world – that, ‘for the most part black women don’t expect to be able to bring their full selves to the workplace and still get ahead’.12 Others have spoken of the visibility/invisibility conundrum: being visible because of your colour but at the same time invisible since you can sometimes be mistaken as part of the support function and not leadership.13 The coach has to explore this world, which might be so different from their own, to be able to ask the questions that really matter – from the perspective of the coachee. This is true of any coaching assignment but is more so, indeed is a fundamental requirement, when issues of race are an obvious part of the coaching engagement.

Paul Winum offers another nugget as to how coaches can approach the issue of race. In his case study of an African American executive for whom he had been called in to offer development support, Winum notes that the issue of race had never been discussed with the client as it related to his placement nor had the ‘political’ implications of his success or failure been approached.14 When Winum as the coach raised this frontally, it actually had the impact of accelerating trust. Winum’s case study is worth reading as the first in a respected coaching journal to tackle this central issue; we trust others will build upon it.

In this chapter, and the one before it, we considered individual difference, of many kinds. Now we step the complexity up a notch, adding the next crucial element that all coaching must take into account: the context.