CHAPTER 10

ADVANCED COACHING: COACHING AND CAREER TRANSITIONS

Anne Scoular and Charles Glass

Freud said only two things really matter – love and work.

When he wrote that, about 100 years ago, average life expectancy was around 50,1 meaning a working life of perhaps 35 years. Now, with average life expectancy approaching 100 for the young, and not much less for those currently mid-career, we might be at work for more than six decades.2

It will seem even longer for those who are miserable. Or just unfulfilled, or bored. But by contrast there really are people who love their work, who would do it even if they weren’t paid, who are lit up with pleasure when talking about it. These are the people studied by Herminia Ibarra and described in her book Working Identity.3 Many people in the unfulfilled camp would love to get into that tiny high-satisfaction, high-achieving minority. Career coaching can help people get there.

This chapter is in two sections:

- 1In ‘The changing context’ Anne describes the forces ripping old-fashioned careers apart. And outlines a new type of career coaching, combining useful careers advice with the turbo-charge of Big Five coaching.

- 2In ‘Career coaching tools’ Charles Glass, co-founder of The Professional Career Partnership (www.thepcp.com) and career coaching expert, shares tips and techniques for the three main types of career coaching:

- (a)career management;

- (b)career transitions;

- (c)the ‘Act Three’ life.

1. The changing context

An ancestor of mine (i.e. Anne’s) was, in successive Victorian censuses, an apprentice silver polisher, Secretary to Singing School, hotel proprietor and Of No Occupation. In between he briefly managed Charles Dickens’ North American tour – before Dickens fired him for incompetence. So having to pick yourself up and start again and/or reinvent yourself every decade isn’t new – it just feels rough when it happens to us.

But our own times are making more career demands than ever before. New things we have to navigate include:

- ●fast-changing technology;

- ●cross-border teams;

- ●‘matrix’ management: the boss is in Hong Kong, the team across several time zones, and you meet in person just once a quarter – but have to deliver;

- ●rapid production shifts to ever-cheaper sites around the world – then back;

- ●savage media scrutiny 24/7;

- ●transnational complexity: the EU, globalisation, etc.;

- ●disaggregated careers: the ‘millennial’ generation born between 1977 and 1997, will likely have 15 to 20 jobs over the course of their working lives;4

- ●and such profound economic and political uncertainty, that the Financial Times warns of the need to rebuild capitalism itself.5

It’s a wild ride, and even the most capable person sometimes needs help to navigate the rapids.

Of course, there are many new positives to balance the new challenges: flexible working, the joys technology can bring, absurdly high financial reward for a few, etc. But some of the things that keep people going aren’t healthy: alcohol, excess of testosterone, cocaine. (I once asked in wonderment, when hearing of working round the clock, how do people do it? My interlocutor gave me a sharp look, and I realised.)

And there’s another thing. We’re living longer – much longer.

The new longevity

Some neuroscientists think the person who will live 1,000 years has already been born.6

Professor Tom Kirkwood isn’t one of them, but he did point out that, contrary to popular belief, ageing is not inevitable: the human body is not programmed to die (yes, you read that right), and as a result we are entering nothing less than an entirely new period of human history.7 For millenia, most of our ancestors lived to around 35. But now, Jeanne Calment died in France aged 122, H.M. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother aged 101, and several of my friends’ parents are healthy and active in their 90s. They are no longer exceptional: the UK Office for National Statistics shows UK female average life expectancy at age 65 is now 86.68 – and ‘average’ life expectancy of course means that half live longer!

The funding gap

So we’re living longer than ever before in human history: good.

But we can’t afford it: not good. There is a vast gulf currently opening up between what it will cost us to pay for those many more years, and what we have saved. This ‘funding gap’ is caused by many things, including pensions being mauled by politicians, and battered by economic crises and human malfeasance, but also by social change. Current drivers of the funding gap, and its career consequences, include:

- ●Corporate incompetence, ruthless debt leveraging by the greedier end of private equity, and downright theft, leading to the collapse of firms and pension schemes on which millions of people relied.

- ●Even before the various market and firm crashes, 9 million people in the UK already had inadequate pension provision – approaching half the workforce.9

- ●Defined benefit (DB) pensions have almost vanished, switching the risk from employers to individuals.

- ●Serial marriage and/or later childbearing means many will have children still at home, and education to fund, in their sixties, while longevity means some are at the same time caring for still-living very elderly parents.

- ●Generation Y has the ‘triple whammy’ of the baby boomer generation ahead of them over-consuming assets and leaving behind systemic debt; while they carry student debt; yet seek greater work–life balance.

There are only four ways to tackle the funding gap: save more, consume less, work longer, die sooner. Given that choice, the zeitgeist is going for ‘work longer’.*

* Though the planet would doubtless prefer we tackled it by consuming less.

- ●work can be a pretty challenging place;

- ●but tempting though it may be to run away, we’ll actually need to do it more rather than less;

- ●(help!).

So let’s dig deeper into what career coaching is and does.

The new career coaching

The old model didn’t work. ‘I was given some tests at 13 and told I should be a hairdresser,’ said one investment banker, still resentful 30 years later. In early 2010 the UK Government’s own report into its official careers advice service recommended, astonishingly, that it be shut down in its entirety because the Inquiry ‘barely heard a good word to say for it’.10 In the private sector, a minority of adults get ‘outplacement’, as part of a redundancy package, but this has historically been solely advice-based.

But the need is there, and will become increasingly urgent. The solution is simple: keep the useful bits from traditional career advice, and add proper coaching. Charles Glass, who generously shares his experience in the next part of this chapter, believes the optimal mix, the powerful blend that makes up the ‘new career coaching’, is 80 per cent Big Five coaching and 20 per cent careers advice.* This inverts the traditional model, which didn’t work well because the advisor typically spent most of their time telling. However, after 20 years helping thousands of businesspeople across Europe with successful career transitions, Charles is also convinced that switching to pure Big Five coaching would also be a mistake, as there are some things people do benefit from knowing: how best to work with headhunters and prepare for interviews, for example. The key to success is to maintain the 80/20 ratio, mostly coaching but keeping a judicious eye out for the other things Charles outlines below.

* The ratio shifts over time. Early in people’s careers, it may be higher on telling: I could certainly have used a bit more useful advice at the outset about how invisible office politics worked, for example. But business coaches and leaders typically meet with people who are beyond those first few years and hence are at the stage where the optimal 80/20 kicks in.

In the next part of this chapter, Charles assumes you already know about the 80 per cent, i.e. Big Five coaching (see Chapter 5), and concentrates on the remaining 20 per cent: the additional skill and content knowledge specific to great career coaching.

2. Career coaching tools

(This is Charles writing.) We presume you, or the coach you’re bringing in, can ‘Big Five’ coach, and well. And as always in coaching you need to be yourself: executives don’t want a cipher, they want to spark and engage with a real human. As we have said, that’s 80 per cent of career coaching, but you also need a little more. The remaining 20 per cent is information people need about how the world of work operates, from large-scale structures right down to the impact of something as seemingly irrelevant as the seasons of the year.

First, let’s clear up a distinction between two separate terms. They’re often bandied about interchangeably, but there is an important difference. Career management is where you have a choice; in career transitions, you don’t.

In the first case, clients are asking, ‘what do I want to do when I grow up’, or musing whether they should go off and do something completely different. They’re wondering, but there’s no driver for immediate change. In the second, they’ve been fired. Or made redundant, or their partner’s job is being moved to another country – whatever the reason, there’s no longer any musing, change is forced upon them.

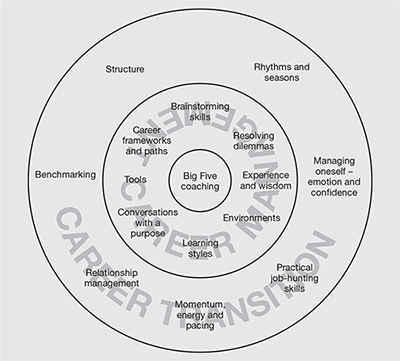

In this section we consider both in turn, then later in the chapter discuss coaching for the new ‘third stage’ career. All three aspects of career coaching are integrated in Figure 10.1.

(a) Career management

In career management, there’s no rush. The client wants to think about their career, but they’re currently employed; there’s no ‘burning platform’ to make them jump – but they’re restless enough to go and talk to a careers coach.

They come with different angles on the question. Some say, ‘I never really decided to be [in finance, law, etc.], I just got into it and here I am 20 years later . . . ’ There is a niggle at the back of their mind that they never really made a choice – is now the time to take ‘control’? Others are successful, maybe in their mid-40s or 50s, and want another big job – but in a completely fresh sector, and don’t know how to switch across. Still others hanker after finding out once and for all ‘what I want to do when I grow up’.

Particularly with the last group, the first piece of the 20 per cent can be to disabuse clients of some common misconceptions. Some think the ideal career for them is out there, waiting, and their task is to find it. We can tell them that they’re not looking for the one, the ideal, career – there are many ways to skin the careers cat. You might even have two jobs on the go at once, or sequentially, each fulfilling different aspects of your financial and other needs. Similarly, a lot of people think they haven’t worked out what they should do, but everyone else has – but actually only about 20 per cent of people do have this clarity of direction, and it can change even for them. Another common misconception is that the coach has the answer; as in general coaching, we don’t, they do. So in a sense we’re again here starting with contracting – in this case gently challenging where necessary, and opening up the possibilities of what the task and process might be.

The next is goalsetting: what does this particular person want to achieve from the career management conversation? And so on, applying the GROW Model, listening, questioning, and working non-directively.

Beyond that, there are eight specific elements to good career management coaching. They are:

- ●tools for information gathering;

- ●career frameworks and paths;

- ●brainstorming;

- ●resolving dilemmas;

- ●experience and wisdom;

- ●environments;

- ●learning styles; and

- ●conversations with a purpose.

We consider each in turn below. This doesn’t mean this is a neatly sequenced process, it often isn’t. But if at some point in the coaching you bring in these eight elements, you will be helping your client build a surer footing for their career explorations.

Tools for information gathering

First, the diagnostic phase, where we help the client identify their motivations, strengths, values and interests.

The aim here is not to get to an absolute truth, but to something clients can use as a basis for their thinking on their career. My own starting point is a question framework developed by our organisation, and we’ll often spend the entire first two sessions working through it. It covers not just the obvious material such as their achievements, but also, importantly, what they have enjoyed – even if one has to go back to childhood to find examples. (Many people have sadly got into a deeply ingrained habit of not enjoying work and finding their pleasures outside it – or just working harder.) The objective here is to dig out the six to seven things that are most important to them.

You might wonder why we don’t begin with general strengths instruments such as the VIA, or personality psychometrics. While these are often useful in general business coaching, what we are looking for here is the utterly unique way the genetic/personality/ability hand you were dealt has come together over your life to date. For example, Extravert A’s drama teacher in the sixth form made a big impact and they have developed terrific public speaking ability, whereas Extravert B had a critical parent who was a research scientist, so they have a deeply ingrained habit of getting their facts right before they speak. In other words, there has been a constant interplay between person and their context, and the career coach needs to understand the key things that have fused in that crucible.

Career coaches who do want to use psychometrics find a surprising dearth of them. The Strong Interest Inventory (see https://eu.themyersbriggs.com), is particularly useful for people considering early career change, and the Hogan suite (particularly the MVPI, which identifies one’s values) for those with more experience, but there still isn’t a really good purpose-built career tool.

Personality psychometrics are, perhaps surprisingly, of less assistance; good businesspeople are usually already well equipped with insight into themselves and others from 360° and structured feedback over the years, and are familiar with MBTI or one or more of the trait instruments such as 16PF, NEO and FIRO-B. (If not, plugging that gap can of course be an early ‘win’ in the career coaching process.)

Career frameworks and paths

Career coaches need to know how particular careers work. You don’t need to be an expert – indeed part of the art of career coaching lies in knowing a little about a lot! – but some quick advice can save clients from losing valuable time in their job exploration. Professional careers such as medicine need qualifications gained at the outset, and it is difficult – though not absolutely impossible – to enter them later in life. Other qualifications, in personnel and marketing for example, can be picked up while you’re working, which is important for those who can’t afford years off to retrain. People often get stuck in career changes because they are simply lacking information – they just don’t know what other career possibilities are out there.

So different occupations have different entry mechanisms and structures. So, too, do the individual experiences of work that we call a ‘career’.

Particularly relevant to mid- and later-stage transitions is the portfolio career, where one puts together a variety of ways of earning a living – a ‘portfolio’ of work. (Business coaches themselves are a good example of this: they often have a contract for one or two days per week with a previous employer; see business coaching clients; and also do consultancy on their specialist field, perhaps strategy, finance or talent management.)

If people are considering portfolio working as an option, coaches can make two useful contributions: to get them to consider whether they are psychologically suited to working this way, and to encourage them to think about building a sustainable mix into the portfolio.

On whether they are suited, useful questions include:

- ●How much can you cope with uncertainty, not just of income, but of corporate buying processes taking a long time, requiring sudden changes, etc.?

- ●Do you need people around you, or can you cope on your own?

- ●Do you prefer structure and order, or can you thrive on the challenge of having to figure it out for yourself?

These questions may not come as a surprise to people, but the other aspect, of getting the mix of portfolio activities right, is often more unexpected. The point is that different types of potential portfolio work have broadly three different paces. There is:

- ●short notice, intensive, and well paid – for example, consultancy projects, or designing and implementing a training course;

- ●steady – for example, bookkeeping for a healthy business – they will need you to work for x days per month, every month, indefinitely, or a non-executive director (NED) role with a term of years;

- ●work you can schedule yourself – for example, writing a specialist book, or blogging – or indeed coaching, where you can fit client meetings around other commitments.

Ideally, clients need a mix of all three for a reasonable balance of life and consistent income. The intensive high-paid work is lucrative, but while projects are on, they’re all-consuming. Steady work pays less, but enables the client to sleep at night knowing at least the mortgage is covered each month, and work you can pick up and put down is invaluable for making fulfilling use of the time between the intensive high-paid bursts.

Brainstorming

Career coaches need to have a way of brainstorming with clients. It’s very rare that people end up doing something without there being a clue to it in the past – but for some, reconnecting with that something can be hard work.

Different coaches find different ways to do this: the key is to find a way to help people remove limitations in their thinking. For example, in their current job, lawyers focus intently on words, so we might ask them to work instead with the visual part of their brain by drawing. Another tip is to spend significant time discussing hobbies and interests at the school and university stage: this is often helpful in bringing forgotten themes to the surface.

Resolving dilemmas

If the issue was simple, the client wouldn’t need you. So there is almost always a dilemma at the heart of career coaching. Typically in financial centres it’s being unhappy in an existing job, but knowing the more fulfilling roles elsewhere pay less. Or wanting to go right to the top, but knowing it could mean violating core values. Or having young children who need their parents, but at precisely the stage when career demands are also greatest.

Clients find myriad different solutions, each right for their unique needs and circumstances, but after many years of watching I have seen some patterns emerge. One can, for example, solve a dilemma sequentially over time – I do this now, and that then; or by slicing a week: four days in the current job, one day studying for the new one.

Experience and wisdom

To be a good career coach I firmly believe you need to have lived quite a bit, and to have reflected upon that experience. Though you are not being directive (‘if I were you I would . . .’ is as unhelpful here as in all other domains of coaching!) you do need to have things that come to mind to offer as ‘paper tigers’ to clients, or to challenge or stimulate their thinking. Having a wider context of life and work is helpful in negotiating the cul-de-sacs, limitations and preconceptions that clients have often fallen into.

Environments

Sometimes the solution is actually simpler than people think: they may be in the right career, but in the wrong sector of it – so the wrong environment. You could be a lawyer in the financial district of the City of London, or in the Civil Service in Whitehall. The latter is only a few miles down the river Thames, and the job has the same title, but the atmosphere is quite different. Working ‘in-house’ as a lawyer in a large public company is a different environment again. People often think they know the differences, but can find it an eye-opener to go and investigate properly. I have found about 30 per cent of the time, switching to a different environment within the same career is all it takes for them to be much happier.

Learning styles

There are stages to career change, and different learning styles incline people to prefer different stages. The best career change involves sitting in a room and talking about it; then going out and hunting, then coming back and digesting the information, then out again. It is sadly the case that extraverts do fall into jobs more, as they’re naturally inclined to get out where the jobs are; introverts might need to be encouraged to move from reflection to action.

Writers in the field concentrate on particular stages, too. The bestselling Richard Bolles’ What Color Is Your Parachute?11 focuses on analysis. Herminia Ibarra’s Working Identity by contrast encourages exploration.12 In reality, every career process needs both. Coaches need to keep an eye on whether clients are skimping on less preferred but critical parts of the process.

‘Conversations with a purpose’

This is networking, but I prefer the term ‘conversations with a purpose’ as that’s what they are. Most people know this is important, but they feel embarrassed about it and also do it badly, i.e. without clear planning as to its purpose. Yet the more senior the career being managed, the more crucial this core skill is. A light touch on the rudder is often all that’s needed: when people see this as a business task rather than asking someone for a job, they apply to it the standard methods they already know from their business life: clarifying their business proposition, listing targets, developing question lists, sequencing the action plan, etc. Once they understand that other people enjoy being asked for advice and that it is a mark of respect, they normally find the process surprisingly effective and even enjoyable. This needs to be supported by an appropriate social media presence: see the following box for advice from an expert headhunter and career coach Anna Ponton on working LinkedIn for your career.*

* Anna Ponton is a Partner and Head of Coaching Practice at global search firm Odgers Berndtson www.odgersberndtson.com.

(b) Career transitions

In career transitions, everything we’ve said about career management remains true, but in addition there is a sense of urgency. They’ve been made redundant, their company has gone under – whatever has happened, their situation has changed abruptly. Even if they saw it coming, now it’s different: it has actually happened.

That abruptness, that urgency, mean the coaching carries an additional load it didn’t have in career management. The client may have taken a knock to their confidence and need to rebuild it. If it has been a ‘clean’ redundancy, with perhaps an entire division closed down, so nothing personal, then this may not be so, but if the job has gone wrong – and over a long time, as they usually do – then the client’s confidence may well have been eroded (in which case see Chapter 6 for Carol Kauffman’s indispensable ‘4 steps to confidence’ technique). Career transition work also tends to be more about the whole life agenda. They’re in a jam, you are offered to them – if they really decide to work with you, clients often then take a ‘boots and all’ approach and open up about their whole life situation, in ways ordinary executive coaching and even career management coaching clients don’t.

Yet paradoxically, it’s actually easier to work with clients in career transition – they have to do something. In my experience, less than 40 per cent of career management clients who are currently successful do actually move. Career transition clients don’t have the luxury of that decision – they’ve already moved, even if it wasn’t their idea. This is why a clear majority of people who have been made redundant will tell you, two years later, ‘It was the best thing that ever happened to me.’ They were forced to take their life into their own hands. Recent examples include a lawyer who set up her own art gallery, a trader who became a driving instructor and now trains examiners, and a junior professional who became an international development consultant – it was just what they needed, though it didn’t seem so at the time.

In career transition coaching, the largest part of the work is still mainstream business coaching. Plus the additional career management tasks discussed above. But because people now don’t have a job, there is another layer. The essence is to help them rebuild for themselves the structure and containment they have suddenly lost. They don’t have to get up and travel to work; they’re accountable to no one; a chunk of their social network has vanished; and they probably feel to some degree a failure. Hence much of the task is to help them self-manage, replacing the exoskeleton they have lost.

So, in addition to the core 80 per cent of Big Five coaching, and the issues in career management outlined above, there are seven further elements to career transition:

- ●structure;

- ●rhythms and seasons;

- ●managing oneself: emotions and confidence;

- ●practical job-hunting skills;

- ●momentum, energy and pacing;

- ●relationship management; and

- ●benchmarking.

Figure 10.1 The three levels of career coaching

Structure

There actually is one piece of structure: the time by which they need to get a job, before the money runs out. If there happened to be no financial pressure, then it would in effect be back to being a career management conversation – ‘What do I want to do with the rest of my life?’ So by definition, in career transition coaching the money is going to run out at some point. They may be able to survive for a month, or six months, or a year, but there is still hanging over the conversation the additional pressure of ‘I need a job’. The coach needs to help them add some more, and more helpful, landmarks. I tell people that no one can job-search for more than two days a week, or at most, three. That gives shape to their week straight away: two to three days on the main task. Next question, how are they going to fill the remaining time usefully? It may feel indulgent, but if, for example, they finally tackle the research project they’ve always been interested in, or write, or make that contribution to the community, then apart from anything else, it gives them something interesting to talk about in interview when the conversation strays to chat.

Part of this early task is also to help them let out some of the emotion – the very presence of that end marker can cause panic, or at least anxiety. There will also almost always be emotional baggage arising from the disengagement from the previous job. That needs to be processed, not swallowed down, or it will come back and bite. This is mostly done by that core coaching technique – just listening. For those where the emotion lingers, and risks becoming entrenched into bitterness, I find the solution is forgiveness. If, having had the chance to air their feelings, whatever they are – frustration, anger, fear – they can get to the point of forgiving the company or individual(s) involved, they are well on the way to regaining a healthy balance.

Structure also applies to managing money. If people have enough to last six months if they spend a little on themselves, or seven if they deny themselves altogether, they’re more likely to get a job if they do the former. It’s hard to convince people of this, particularly if they’re in early high-anxiety mode, but it is true. Funnily enough, it then becomes a little benchmark of success. If they come into a session, smile ruefully and say they have signed up for the woodworking course after all, it shows their anxiety has been managed down, and they have started to take the kind of action that will sustain them through a long haul, if that’s what it turns out to be. (And then, of course, it hopefully won’t be.)

Rhythms and seasons

The toughest time to be given a career transition client is November to January (in the northern hemisphere; April in the southern). When we are in work, inside buildings, dashing to and fro, we notice the seasons less, but when that is taken away we suddenly become much more aware of the dark and cold of the approach of winter. And Christmas is coming up, other people are partying and buying presents, but the client is not sure how much they can afford to spend. By February it’s getting lighter, and in spring career coaches see a noticeable change in their clients – the sap rises, and their energy with it. We also have ingrained from education and childhood, memories of September and January being points when we start afresh, and they too can give a fillip – but coach and client need to be aware of the winter dip, plan strategies to combat it, so far as possible, and know that it exists and it too, will pass.

Dealing with lulls in the job-hunting process is another kind of rhythm to be aware of and plan ahead for. Preparing for the summer and Christmas lulls by increasing the activity levels in the run-up to them, then actively using the lulls for other purposes, keeps people fresh and positive for when the interview activity picks up again.

Managing oneself: emotions and confidence

Coaches may wonder how they can help do this on a sustained basis – but this is where Carol Kauffman’s work is an invaluable resource for us. We have already discussed building confidence in Chapter 6. For helping people to manage their emotional state positively, so as to get to and stay at peak performance despite all that is happening (or not happening), see the section on ‘F’, Feelings, in Carol’s several YouTube videos on the PERFECT model, and her article on it in Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice.13

Practical job-hunting skills

Clients think this is what they are coming for, but in fact it’s the least of the work of the career coach – mobilising the client’s own resources is always the key. But there are skills to be taught, if the client doesn’t already have them: how to use agencies, how to prepare for interviews, how to work best with headhunters. There is a terrific new resource here: Jenny Rogers’ Coaching for Careers: A Practical Guide for Coaches, which has a huge quantity of indispensable information on interview preparation, writing CVs, brand identity, and much else.14 If career coaching is even a small part of your coaching life, then this book is a key part of your toolkit (and indeed, some clients might find it valuable too).

Momentum, energy and pacing

The coach may need to help clients build and maintain their energy – career transition is tough, personal, hard work, so what energises them so they can keep going? The starting point is simply to ask: many people are well aware of what works best for them to get to and stay at their peak.

I have already noted above that you can only do so much job hunting in a week. In the rest of the time I advise clients to go and learn something/contribute somewhere/do something creative. These are all valuable antidotes to depression. It is also vitally important that they put physical activity into the mix – being in shape makes a big difference. For some people, this can be one of the great ‘pluses’ of the enforced time off: it’s finally that chance to get fit again. Or even, very fit indeed: fit enough to climb Mt Kilimanjaro, cycle from Land’s End to John o’ Groats, run the New York, Berlin and London marathons, or sail across the Atlantic – all of which people we know have actually done during career transitions.

For the exercise-phobes such prospects might be very unappealing indeed, but I’m afraid they need to do something. It is absolutely crucial, to ward off depression and maintain their energy at the level they will need, to build in more regular exercise that they probably managed in the stressful lead-up to their transition. For the erstwhile sloths, the proper advice is of course always that they should see their doctor, or a trained exercise specialist, to plan a safe programme. Building the regular exercise sessions in can then have the added benefit of adding some of that important structure!

Relationship management

Another task clients need to prepare for is relationship management: it’s not easy to be asked for the fourth time in a day how it’s going. Just as people are taught the need for an ‘elevator pitch’ on sales training courses, so in career transition people need to work up a phrase for the inevitable moment when someone turns to them and asks, ‘And what do you do?’

The greatest pressure will come from those closest to them. Family and friends are going to be concerned, perhaps anxious, and can intentionally or not put pressure on the client. Managing this is obviously a matter of much more than developing an ‘elevator pitch’ equivalent, but it is readily tackled with normal coaching: ‘What are going to be the issues here do you think? And how could you best tackle them?’

Benchmarking

People want to know they’re doing all right. You could always do more job hunting – and if that’s their only criterion they will always be depressed. Often people are too hard on themselves and then they don’t interview properly.

This is classic ‘20 per cent’ territory. I tell clients, as you’ve already seen, that you can’t job hunt more than three days a week, and that two to three job-hunt activities a week (or more, or less, depending on their particular sector, context or circumstances) is a solid achievement. In other words, I give them a benchmark.

Then, as ever, it’s back to the 80 per cent: what other benchmarks can we develop together, in both the career transition part of their week and in the essential other parts? One might be physical: jogging the perimeter of the park in under 40 minutes (or the mightier feats mentioned above), or it might be getting the children through their forthcoming big exams, or being elected a school governor, or onto the board of that charity they’ve always wanted to help.

(c) ‘Act Three’ career coaching

For years career management and career transition were it. Now there’s a third part to work: we’ve moved from ‘retirement’ to ‘Act Three’ – a whole new stage of working life.

With increased longevity, some people need to continue working longer than they anticipated, and others just want to: they are able people, still at their intellectual, social and physical peak. Much of what we suggested above about the ‘portfolio’ career will apply, but there are fewer well-trodden paths to follow in this new third act to people’s lives and careers: how do they go about it?

We can help.

First, you’ll observe it’s actually the same split as in the earlier stages of working life: some people will want career management (how can I make this the most fulfilling stage of my life?) and others will be in enforced career transition (I need to work longer to fund my pension gap). So the principles above still apply: for the career management people, it’s structuring their exploration and for those who have to find work, it’s all the career management processes plus the additional techniques of career transition.

And underlying them both is, again, the Big Five: coaching works, and it works particularly well with a group such as this entering uncharted territory.

But perhaps the needle needs to shift: the right ratio for mainstream career work is, we believe, 80:20, in other words, 80 per cent coaching topped up by a little judicious nudging from our professional expertise. There are no rules yet for ‘Act Three’ career coaching; we are the generation who will need to develop them. But we think it’s probably closer to 90:10. You can’t tell an intelligent resourceful 55-year-old, with all those years of experience, hidden interests and personal connections, what they should do with the remaining decades of their working life, but you can coach out of them their own hopes, fears, gifts, strategies and plans.

What is the remaining 10 per cent? There are at least four parts to it:

- ●what people want from work;

- ●pace in the ‘Act Three’ career;

- ●risk and reward; and

- ●practical input.

What people want from work

Or indeed need. Salary matters, but it is in some senses the least important. Time and again the things people say they are looking for in this stage of their working life are:

- ●meaning, purpose, making a difference;

- ●belonging;

- ●identity;

- ●learning/challenge; and

- ●a framework to life.

So the first step is to help people work out what really matters to them. It may be that they are actively involved in a large extended family, or Church, or community of hobbyists, so their need to belong is amply met outside work. Conversely, people who have thrown everything into a successful career might find it gave them, without their realising it, framework and identity and purpose and learning and the place they belonged – but all five have now vanished. So for them, much of this third phase will need to be built afresh. Eventually that could be exciting, but right now it probably feels very strange and unfamiliar, and they may well relish some good, strong non-directive coaching, which structures the process of some of their thinking and exploration while drawing the content very much out of them.

Jon Erik Haug, a very senior Norwegian businessman, kept a diary during the first year of just such a transition – in the following box he kindly shares his story.

With regard to identity, one practical question is how are they going to describe themselves? It’s the answer to that question at parties again – but whereas the recently redundant person needs to come up with something quickly, for someone embarking on the ‘third phase’, developing this answer is part of the fun, and they may like to try several on for size for a while. An interim phrase to say to other people may be useful to provide ‘cover’ while the exploring is going on (perhaps for years!).

Pace in the ‘Act Three’ career

This is similar to constructing a portfolio career as we discussed above, but the scope of decisions now is broader. Clients will of course have many thoughts already on what they want to do, but to give them food for thought we ask, do they want work that:

- ●is controllable; or

- ●involves a certain number of days per week; or

- ●where they work hard in bursts, with gaps between projects?

People typically start by thinking in terms of X number of days per week, but in fact intensive bursts, such as are needed in major consultancy projects, or interim management roles, may suit them better. These can then be balanced with the third element, regular work that is able to be moved around during bursts, is not time-linked and is usually controllable by the individual, to fill in the gaps.

Risk and reward

There’s a big difference here between ‘retirement’ and third phase careers. If you retire, and were an accountant, people suddenly expect you to do the accounts for the local cricket club, or whatever you’re involved with, and ‘of course,’ pro bono. Act Three careerists aren’t having any of that – they’re still working, though differently, they have been earning well to date and see no reason why that should change. Even if they don’t need to earn, proper remuneration is, as one competitive client said to me, ‘a way of keeping score’.

The risk in third phase careers is of a different kind. It is important not to do the wrong thing, as there is often quite a high level of moral investment in commitments people make at this point. Once in, it’s therefore hard to extricate oneself, so even if there is a funding gap and a need to keep earning, the coach can usefully deploy the O of the GROW Model, working with the client to explore other options, checking each one out thoroughly for not just its upsides, but its potential risks.

Practical input

At this stage it’s generally unlikely that people will get work through conventional channels such as advertising, so networking will be absolutely crucial. Many people don’t know how to do it effectively. The vital tool here is the process Herminia Ibarra describes in her book, Working Identity: for a summary, see below.

They can also use briefing on particular routes to third phase work. In the UK, for example, the Public Appointments Office of the Cabinet Office is the starting point for around 18,500 appointments to boards and committees of an extraordinary variety of local and national bodies. The particular process varies from country to country, and securing posts in international organisations is even more arcane. In most countries the pressure is on to make such appointments more transparent and accessible, so you could in theory equip yourself with the correct and up-to-date information from websites and published guidelines in order to brief your clients – but in practice, it’s usually far more efficient to ally yourself with a well-informed local specialist in this area.

Another area where specialist advice is important is whether or not to take on non-executive directorships. Requirements for this vary from country to country, and in some jurisdictions it can involve individual personal legal liability, so specialist legal advice should be obtained if this is under consideration.

The most successful career changes

Professor Herminia Ibarra of London Business School investigated career changes, but more specifically, the career process of people who have truly made it, who adore what they do, who have achieved everything they want from work – material or worldly success, spiritual satisfaction, deep peace – the kind of people who say, ‘work is more fun than fun’. She found none of them had got there by the traditional planned route. Instead the process was iterative – exploring here, learning there, stepping forward and back, taking time to think and equally making time to act. From the research she has developed a series of guidelines, or ‘unconventional career strategies’.

She advocates, for example, exploratory steps, perhaps done outside the current job to minimise risk, and seeking out new people – a ‘strategy of small wins, in which incremental gains lead you to more profound changes’.15 And emphasises the importance of allowing oneself a transitional period, which may sometimes feel odd, but when important background mental processing is happening. Each of her nine ‘Unconventional Strategies’ has useful, practical pointers for career changers and those of us coaching them. For more see her invaluable book Working Identity, which describes the process in full; most of the successful leadership career coaches I know regularly give their clients a copy.

Plenty to be going on with! But what of the client where you pour in all of the above, but, frustratingly, they don’t do anything?! It seems to fall on deaf ears, or they shuffle their feet in the next coaching session, having done not very much . . . Or the cynical, the unenergised: the demotivated. This is a crucial issue in all coaching, and we turn to it in the next chapter.