CHAPTER TEN

THE ROLE OF SENIOR EXECUTIVES

IN LEADING NEW GROWTH

How should senior executives allocate their time and energy across all of the businesses and initiatives that demand their attention? How should their oversight of sustaining innovations differ from their mode of management in disruptive situations? Is the creation of new growth businesses inherently an idiosyncratic, ad hoc undertaking, or might it be possible to create a repeatable process that successfully generates wave after wave of disruptive growth?

The senior executives of a company that seeks repeatedly to create new waves of disruptive growth have three jobs. The first is a near-term assignment: personally to stand astride the interface between disruptive growth businesses and the mainstream businesses to determine through judgment which of the corporation’s resources and processes should be imposed on the new business, and which should not. The second is a longer-term responsibility: to shepherd the creation of a process that we call a “disruptive growth engine,” which capably and repeatedly launches successful growth businesses. The third responsibility is perpetual: to sense when the circumstances are changing, and to keep teaching others to recognize these signals. Because the effectiveness of any strategy is contingent on the circumstance, senior executives need to look to the horizon (which often is at the low end of the market or in nonconsumption) for evidence that the basis of competition is changing, and then initiate projects and acquisitions to ensure that the corporation responds to the changing circumstance as an opportunity for growth and not as a threat to be defended against.1

Standing Astride the Sustaining–Disruptive Interface

Because processes begin to coalesce within a group that is confronted repeatedly with doing the same task, the engine that propels accomplishment in well-run companies gradually becomes less dependent on the capabilities of individual people, and becomes instead embedded in processes, as we described in chapter 7. After successful companies find their initial disruptive foothold, the task that recurs repeatedly is sustaining innovation, not disruption. Well-oiled, capable processes for successfully addressing sustaining opportunities have therefore coalesced in most successful companies. We know of no companies, however, that as yet have built processes for dealing with disruption—because launching disruptive businesses has not yet been a recurrent task.2

At present, therefore, the ability to create growth businesses through disruption resides in companies’ resources, and for reasons we’ll explore in this chapter, the most critical of these resources is the CEO or another very senior executive with comparable influence. We say “at present” because it does not always need to be so. If a company tackles the task of creating disruptive growth again and again, the ability to create successful disruptive growth businesses can become ensconced in a process as well—a process that this chapter calls a disruptive growth engine. Although we know of no company that has yet developed such an engine, we believe it is possible and propose four critical steps that senior executives can take to do so. A company that succeeds in creating a disruptive growth engine will place itself on a predictable path to profitable growth, consistently skating to the money-making opportunities of the future.

A Theory of Senior Executive Involvement

Until processes that can competently manage disruptive innovation have coalesced, the personal oversight of a senior executive is one of the most crucial resources that disruptive businesses need to reach success. One of the most discouraging dimensions of senior executives’ lives is the refrain by writers of many management books that they must be involved in order to fix whatever problem the book is about. Corporate ethics, shareholder value, business and product development, acquisitions, corporate citizenship, corporate culture, management development, and process improvement programs are all squeaky wheels that demand executive grease. Senior managers must pay close attention to managing the top line, the bottom line, and all the lines in between. Confronting such cacophony, executives need a good circumstance-based theory of executive involvement—a way to discern the circumstances in which their direct involvement actually is critical to success, and the circumstances in which they should delegate.

One of the most common theories of when senior executives should get involved in a decision and when they should not is based on an attribute of the decision, namely, the magnitude of money at stake. The theory asserts that lower-level managers can make small decisions or ones that involve minor changes, but that only senior executives have sufficient wisdom to make the big calls correctly. Almost every company enacts this theory through policies that give decision-making approval for smaller investments to lower-level executives and elevate big-ticket items for the scrutiny of the senior-most team.

Sometimes this theory accurately predicts the quality of decisions, but sometimes it doesn’t.3 One problem with systems that reflect the send-the-big-decisions-to-the-big-people theory is that the data are in the divisions: There is an asymmetry of information along the vertical dimension of every organization. Reporting systems can indeed elevate the information that senior managers ask for, but the problem is that sometimes senior management doesn’t know what questions need to be asked.4 Senior people in large organizations therefore typically can’t know much beyond what the managers below them choose to divulge. Worse, when midlevel managers have been through a few senior management decision cycles, they learn what the numbers must look like in order for senior management to approve proposals, and they learn what information ought not be presented to senior management because it might “confuse” them. Hence, a good portion of middle managers’ effort is spent winnowing the full amount of information into the particular subset that is required to win senior approval for projects that middle managers already have decided are important. Initiatives that don’t make sense to the middle managers rarely get packaged for the senior people’s consideration. Senior executives envision themselves as making the big decisions, but in fact they most often do not.

Because the senior-most executives in reality cannot participate when and where these decisions actually get made, decision-making processes that work well without senior attention are critical to success in circumstances of sustaining innovation. In the sustaining circumstance when capable processes exist—even in many big-ticket decisions—senior executives typically cannot improve the quality of the decision because of the asymmetry of information that exists.5 This is when the gospel of “driving decisions down to the lowest level” and of “making the lowest level competent” is in fact good news.

Another version of the “size theory” states that large businesses require more active senior management involvement, whereas lower-level managers can cope with the demands of smaller organizational units. Fewer people and fewer assets, the belief goes, mean that less managerial skill is required. Sometimes this is the case, but sometimes it isn’t. Potentially disruptive businesses are small. But with their ill-defined strategies and demanding profitability targets, make-or-break decisions arise with alarming frequency, and such businesses have no processes for making these decisions correctly. In contrast, larger businesses in successful organizations typically have established customers with clearly articulated needs, and have finely honed resource allocation and production processes to serve those needs. The decision-making requirements of these organizations typically transcend the involvement of any given individual, and are typically—and appropriately—met by the orderly functioning of established processes.

Both of these theories get the categories wrong. A better, circumstance-based theory can help managers decide which decisions ought to be made at which levels. For those decisions that the mainstream processes and values were designed to make effectively (sustaining innovations, primarily), less senior executive involvement is needed. It is when senior executives sense that the processes and values of the mainstream organization were not designed to handle important decisions in an organization (which is typically the case in disruptive circumstances) that a senior executive needs to participate. Because the plans for disruptive businesses by definition need to be shaped by different criteria, and because the values of the mainstream business have evolved to weed out the very sorts of ideas that have disruptive potential, disruptive innovation is the category of circumstance in which powerful senior managers must personally be involved. Sustaining innovation is the circumstance in which delegation works effectively. A senior-most executive is the only one who can endorse the use of corporate processes when they are appropriate, and break the grip of those processes and decision rules when they are not.

Another reason why senior executives need to stand astride the interface between sustaining innovations and disruption is that managers of the mainstream business units need to be fully informed of the technological and business model innovations that are developed in the new disruptive business, because disruption often is where the most important improvements for the future of the entire corporation are incubated. If senior managers have properly schooled themselves in sound theories of strategy and management, they can coach the managers of important growth businesses on both the sustaining and disruptive sides of the interface to take the actions that are appropriate to each particular circumstance. Ensuring that deliberate and emergent strategy processes are employed in the right circumstances and that managers are hired whose experience is a match for the problems at hand are ongoing challenges on both sides of the divide.

The Importance of Meddling

One of our favorite teaching case studies about Nypro, Inc., illustrates when and why a senior-most executive needs personally to shepherd the creation of disruptive growth businesses.6 Nypro is an extraordinarily successful custom injection molder of precision plastic parts. Much of the company’s innovative culture and financial success can be attributed to its owner and recently retired CEO, Gordon Lankton.

Nypro’s customers are global manufacturers of health care and microelectronic products. They require worldwide sourcing of plastic components whose complexity and dimensional tolerances demand the most sophisticated molding process capabilities. Nypro seeks to offer a uniform capability from any of its twenty-eight plants—whether in North America, Puerto Rico, Ireland, Mexico, Singapore, or China—under the mantra “Nypro is your local source . . . worldwide.” If Nypro sought to achieve this uniform capability by barring any plant from deviating from standard, company-wide procedures, it would kill innovation at the very level where it best occurs—the plants. Most of the important process innovations that help Nypro to make ever-better products are developed by engineering teams working to solve customer problems in far-flung individual plants, out of the eyesight and earshot of senior management. This situation is a stereotype of the dilemma that confronts most companies in one way or another: Companies need uniform capability but flexibility to change, and senior managers typically can’t even see what innovations are being considered and developed, let alone decide which ones merit investment.

In response to this challenge, Lankton created a system to surface the most important and successful innovations so that he could evaluate which improvements should be adopted by all plants, thereby enabling Nypro to offer a uniform but ever-improving global manufacturing capability. A key element of this system was a monthly financial reporting system that rank-ordered the plants’ performance along a number of important dimensions that Lankton judged to be the drivers of the company’s near-term financial performance and its long-term strategic success. These reports showed, for all to see, which plants were doing better and which needed to improve. Plant managers were evaluated on the measures of plant performance in these reports, and their reputation vis-à-vis each other was affected by the relative ranking of their plants. The system, in other words, provided ample motivation for managers to search for any innovation that would improve their performance and relative ranking.

Lankton created interlocking boards of directors for each plant, so that each board was composed of managers and engineers from several other plants. This kept information flowing among plants. The company augmented this with several global meetings each year for plant managers and engineers, in which they exchanged news about what process and product innovations each had implemented, and what the results had been. In time, there emerged a culture in which managers were intensely competitive to get ahead of each other, and yet were cooperative in sharing the process innovations each had developed.

Lankton watched carefully whenever one plant’s successful innovation began to be adopted by managers at other plants. This was a signal to him that the idea had merit. After several respected managers had copied another plant’s process innovation, Lankton had enough evidence to decide that the innovation should be implemented, and would then mandate that it become a standard practice worldwide. This method tested and validated sustaining innovations first, and then accelerated the implementation of those that had proved to be important.

By the mid-1990s it had become clear to Lankton that Nypro’s world was changing. His engineers could mold millions of complicated plastic parts per month to extremely tight tolerances. Even though there were a few applications that needed even greater precision, Nypro’s capabilities were more than good enough for the majority of the market, and other competitors had improved to compete favorably against Nypro’s cost and quality. Lankton sensed, in other words, that the basis of competition in his markets was beginning to change. He noted that the type of business that had led to Nypro’s success—very high-volume, high-precision molding—wasn’t growing nearly as rapidly as the demand for a wider variety of parts with smaller volumes. Some of these parts demanded high precision as well, but it was the ability to respond quickly with that precision that loomed as the key to success.

Sensing a change of circumstance and crafting a response is a role that only the CEO can fill. Lankton sensed this shift masterfully—but when he left it to the organization to implement the required change, it couldn’t. Here’s what happened.

To prepare Nypro for this shift in the basis of competition, Lankton commissioned a project at the company’s headquarters to develop a machine called “Novaplast” that could be set up in less than a minute.7 The technology’s unique mold design enabled economical, low-pressure molding of a variety of precision parts in short run lengths.

To be consistent with the company’s practice, Lankton chose not to compel all plants to begin using the new machine. He made sure that all managers understood how the technology worked and what its strategic purpose was. He then made the machine available for plant managers to lease, hoping that this approach would minimize barriers to experimentation and adoption—and, as usual, to see whether those whose judgment he had learned to respect cast their votes for the technology. Six of Nypro’s plants leased the machine, but within four months four of those had returned their machines to headquarters. The reason: They had concluded that there just wasn’t any business that could be run economically on the machines. The two plants that kept the Novaplast machine had a long-standing order from a major manufacturer of AA-sized batteries to provide a thin-walled plastic liner that fit inside the metal casing of these batteries. The plants molded millions of these liners every month, and for unique reasons it turned out that the Novaplast machine could crank these parts out with higher yields and lower costs than could Nypro’s conventional high-volume, high-pressure machines.

The end of the teaching case pictures Lankton puzzling about this outcome. Why was it that he had seen so clearly the growing demand for rapid delivery of a widening variety of short-run precision parts, and yet his plants hadn’t been able to land any of that business for their Novaplast machines? Was it a victory or a failure that Novaplast’s ultimate success came from a very high-volume, standard, high-precision part?

The answer is that this is exactly the result we would expect from the processes and values that supported the existing business model. Nypro’s finely honed innovation engine shaped Novaplast as a sustaining technology, because this is exactly what the system was designed to do—to shape every investment to help the company make money in the way it was structured to make money. An organization cannot disrupt itself. It can only implement technologies in ways that sustain its profit or business model. The consequence for Nypro of allowing the standard process to remain in control is that (so far) the company has missed the chance to create a major new disruptive growth business.

To succeed at this disruption, Lankton would have needed to create a sales organization whose compensation structure energized salespeople to pursue this high-variety, low-volume-per-part business. He would have needed to build an operating organization whose processes were tuned to this work and to create measures of performance that were different from those that drove success in the core business. None of the processes of the core business could make these judgment calls correctly. This is why the CEO needs to stand astride the interface between mainstream business units and new disruptive growth businesses.8

Can Any Executive Lead Disruptive Growth?

Because the processes and values of the mainstream business by their very nature are geared to manage sustaining innovation, there is no alternative at the outset to the CEO or someone with comparable power assuming oversight responsibility for disruptive growth. Can only certain of these executives exercise this oversight effectively, or is it possible for any senior person to succeed? We noted in chapter 2 that most of the companies whose stock we wish we had owned in the past fifty years took root with a disruptive strategy. A few—but not many—of these companies subsequently caught or created other waves of disruption that kept the parent corporation growing at a robust pace for a time.

One of our most sobering realizations is that within the population of companies that successfully caught a subsequent wave of disruption and stayed atop their industries, the vast majority were still being run by the company’s founder at the time they tackled the disruption. Only a few companies that were run by professional (non-founder) managers have succeeded in creating new disruptive growth businesses. Table 10-1, although not exhaustive, illustrates what we have sensed.9

Table 10-1

| Founder-Led Companies That Launched New Disruptive Businesses |

||

| Company | Disruptive Growth Business | CEO/Founder |

| Bank One | Monoline credit cards (purchase of First USA) | John McCoya |

| Charles Schwab | Online brokerage | Charles Schwabb |

| Dayton Hudson | Discount retailing (Target Stores) | The Dayton family |

| Hewlett-Packard | Microprocessor-based computers | David Packard |

| IBM | Minicomputers | Thomas Watson Jr.c |

| Intel | Low-end microprocessors (Celeron chip) | Andrew Grove |

| Intuit | QuickBooks small business accounting software; TurboTax personal tax assistance software; putting Quicken money management software online | Scott Cook |

| Microsoft | Internet-based computing; SQL and Access database software; Great Plains business solutions software | Bill Gates |

| Oracle | Centrally served software (applications service provider) | Larry Ellison |

| Quantum | 3.5-inch disk drives | Dave Brown/ Steve Berkley |

| Sony | Transistor-based consumer electronics | Akio Morita |

| Teradyne | Integrated circuit testers based on CMOS processors | Alex d’Arbeloff |

| The Gap | Old Navy low-price-point casual clothing | Mickey Wexler |

| Wal-Mart | Sam’s Club | Sam Walton |

aMcCoy was not the founder, but was the primary architect of the acquisition strategy that drove Bank One to its prominence. | ||

| bThe company’s co-CEO, David Pottruck, strongly assisted Charles Schwab in this effort. | ||

| cAgain, Watson was the son of the founder, but was the primary driver of IBM’s success in mainframe digital computing. | ||

It’s worth noting that these founder-led organizations were also essentially single-industry firms (that is, relatively undiversified when they faced the disruption), which, as chapter 9 noted, can make creating a new disruptive business even harder. We suspect that founders have an advantage in tackling disruption because they not only wield the requisite political clout but also have the self-confidence to override established processes in the interests of pursuing disruptive opportunities. Professional managers, on the other hand, often seem to find it difficult to push in disruptive directions that seem counterintuitive to most other people in the organization.

Table 10-2 shows, however, that there are some exceptions to the principle that only founders seem able to drive disruption. We know of five major companies that were run by professional managers at the time they launched successful disruptions. Of these, Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, and General Electric are all icons of diversification. IBM and Hewlett-Packard were relatively undiversified when their founders launched those companies’ first successful disruptive businesses; hence, they are listed in table 10-1. Later, when professional managers were running the show, these two firms launched or acquired additional disruptive businesses, but did so when the firms had become much more broadly diversified.

We suspect that because the professional managers of the companies listed in table 10-2 undertook their new disruptions in the context of a diversified, multibusiness corporation, it was easier for them to succeed. Although their capabilities as managerial resources were undoubtedly important in these actions, there were precedents and processes for creating or acquiring new businesses and managing them appropriately that assisted the professional CEOs in creating disruptive growth.10

Table 10-2

| Professionally Managed Companies That Launched New Disruptive Businesses |

|

| Company | Disruptive Growth Business |

| General Electric | GE Capital |

| Hewlett-Packard | Ink-jet printers |

| IBM | Personal computers |

| Johnson & Johnson | Glucose monitors, disposable contact lenses, equipment for endoscopic surgery and angioplasty |

| Procter & Gamble | Dryel home dry cleaning, inexpensive power toothbrushes, Crest brand tooth-whitening strips |

Creating a Growth Engine: Embedding

the Ability to Disrupt in a Process

Launching a single successful disruptive business can create years of profitable growth for a company, as GE Capital did for its parent during the years when Jack Welch was at its helm. Disruption blessed Johnson & Johnson’s medical devices and diagnostics group, as we noted in chapter 9. Hewlett-Packard’s disruptive ink-jet printer is now the profit driver of the entire corporation. If it feels so good to disrupt once, why not do it again and again?

If a company launches a sequence of growth businesses, if its leaders repeatedly use the litmus tests for shaping ideas or acquiring nascent disruptions, and if they repeatedly use sound theories to make the other key business-building decisions well, we believe that a predictable, repeatable process for identifying, shaping, and launching successful growth can coalesce. A company that embeds the ability to do this in a process would own a valuable growth engine.

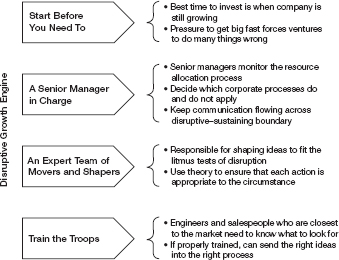

Such an engine would have four critical components, as depicted in figure 10-1. First, it needs to operate rhythmically and by policy, rather than in response to financial developments. This would ensure that new businesses get launched while the corporation is still growing robustly, and that new businesses would not be pressured to grow too big too fast. Second, the CEO or another senior executive who has the confidence and the authority to lead from the top when necessary must lead the effort. This is particularly important in the early years, when success still depends more on resources than on processes. Third, it would establish a small corporate-level group—movers and shapers—whose members develop a practiced, repeatable system for shaping ideas into disruptive business plans that are funded and launched. Fourth, it would include a system for training and retraining people throughout the organization to identify disruptive opportunities and to take them to the movers and shapers.11

Step 1: Start Before You Need To

The best time to invest for growth is, as we noted in chapter 9, when the company is growing. To build what will be a respectable growth business in five years, you have to start now. And you need to add new units to the portfolio of growth businesses in a rhythm that is dictated by the growth needs of the corporation five years hence. Companies that build while they are growing can shield their nascent high-potential businesses from Wall Street pressure, giving each one the time it needs to iterate toward a viable strategy and take off. Keep Wal-Mart in mind. In 2002 it generated nearly $220 billion in revenues. But from the time it opened its first discount store, it took a dozen years in today’s dollars until it passed the billion-dollar revenue threshold. Disruptions need a longer runway before they take off to huge volumes, so you have to start them before your annual report suggests that you’re leveling off.

FIGURE 10 - 1

The Disruptive Growth Engine

The best way to do this is to budget for it—not just an amount of capital set aside to invest in disruptive growth, but a budgeted number of new businesses that need to be launched each year.12 Remember that we are not advocating establishment of a corporate venture capital fund whose structure is predicated on the belief that one cannot predict which investments will and will not pan out. We believe that the process of creating successful growth is capable of much greater predictability if managers use sound theories to shape ideas properly. The needed number of new businesses can therefore be launched each year with not just the hope but the expectation that they will succeed.

Step 2: Appoint a Senior Executive to Shepherd Ideas into the Appropriate Shaping and Resource Allocation Processes

Creating a successful disruptive growth engine requires the careful coaching of the CEO or another senior manager who has the confidence and the power to exempt a venture from an established corporate process, to declare when different processes need to be created, and to ensure that the criteria being used in resource allocation are appropriate to the circumstance of each venture and the needs of the corporation. This executive must be well versed in disruptive innovation theory and should be able to separate ideas with disruptive potential from those that are best deployed on an established sustaining trajectory. The primary job of this manager is to make sure that ideas that are best used to create disruptive footholds are fed into a process that maximizes their chances of success.

As noted earlier, this executive role will change over time. At the outset it will entail monitoring and coaching individual decisions in individual growth businesses. Ultimately it will consist of monitoring the processes for collecting, shaping, and funding ideas; continued coaching and training; and monitoring the winds of changing circumstances in the company’s environment.

Step 3: Create a Team and a Process for Shaping Ideas

We asserted in chapter 1 that lack of interesting growth ideas is rarely a problem in companies that are in danger of losing their growth. The problem is that ideas often lose their disruptive growth potential in the shaping process that they go through in order to get funded. The challenge for this third component of the growth engine is therefore to create a separately operating process through which ideas can be shaped into high-potential disruptions.

Processes like this can be diagrammed at a high level on paper, but they become tangible only as a stable group of people successfully solves similar problems again and again. Senior management should therefore create a core team at the corporate level that is responsible for collecting disruptive innovation ideas and molding them into propositions that fit the litmus tests outlined in chapters 2 through 6 of this book. The members of this team have to understand these theories at a deep level, stick together, and apply them frequently. This experience will help them sense which ideas can and cannot be shaped into exciting disruptions, and to distinguish these from ideas whose potential is sustaining and should be funneled through the shaping and resource allocation process of an established business.

Despite the guidance that we hope this book provides, many dimensions of the strategy that ultimately will prove successful for growth ventures cannot be known at the outset. This means that this core shaping group cannot use the company’s standard strategic planning and budgeting processes when launching disruptive businesses. chapter 8 detailed an equally rigorous discovery-driven planning process for use in disruptive circumstances.13 Members of the core group could coach each new venture’s management on these techniques for strategic planning and budgeting. We are confident that as they do this, their intuition and understanding of the ideas will improve far beyond what we now know and can convey in a limited book such as this.

Step 4: Train the Troops to Identify Disruptive Ideas

The fourth component of a well-functioning disruptive growth engine is the training of the troops, particularly sales, marketing, and engineering employees, because they are best positioned to encounter interesting growth ideas and to scout for small acquisitions with disruptive potential. They should be trained in the language of sustaining and disruptive innovation and absorb a deep understanding of the litmus tests, because it’s crucial that they come to know what kinds of ideas they should channel into the sustaining processes of established business units, what kinds should be directed into disruptive channels, and what ideas have the potential for neither. This is truly a situation in which “making the lowest level competent” will pay off in spades. Capturing ideas for new-growth businesses from people in direct contact with markets and technologies can be far more productive than relying on analyst-laden corporate strategy or business development departments—as long as the troops have the intuition to do the first-level screening and shaping themselves.

Senior executives need to play four roles in managing innovation. First, they must actively coordinate action and decisions when no processes exist to do the coordination. Second, they must break the grip of established processes when a team is confronted with new tasks that require new patterns of communication, coordination and decision making. Third, when recurrent activities and decisions emerge in an organization, executives must create processes to reliably guide and coordinate the work of employees involved. And fourth, because recurrent cultivation of new disruptive growth businesses entails the building and maintenance of multiple simultaneous processes and business models within the corporation, senior executives need to stand astride the interfaces of those organizations—to ensure that useful learning from the new growth businesses flows back into the mainstream, and to ensure that the right resources, processes, and values are always being applied in the right situation.

When an established company first undertakes the creation of a new disruptive growth business, senior executives need to play the first and second roles. Disruption is a new task, and appropriate processes will not exist to handle much of the required coordination and decision making related to the initial projects. Certain of the mainstream organization’s processes need to be pre-empted or broken because they will not facilitate the work that the disruptive team needs to do. To create a growth engine that sustains the corporation’s growth for an extended period, senior executives need to play the third role masterfully, because launching new disruptive businesses needs to become a rhythmic, recurrent task. This entails repeated training for the employees involved, so that they can instinctively identify potentially disruptive ideas and shape them into business plans that will lead to success. The fourth task, which is to stand astride the boundary between disruptive and mainstream businesses, actively monitoring the appropriate flow of resources, processes, and values from the mainstream business into the new one and back again, is the ongoing essence of managing a perpetually growing corporation.

Notes

1. In this chapter we’ll use the term senior executives to refer to men and women in positions such as chairman, vice chairman, CEO, and president. Senior executives who can perform well the leadership roles we describe in this chapter need to have the power and the confidence to declare that certain corporate rules will and will not be followed, given the circumstances that a growth venture is in.

2. As mentioned in chapter 8, Sony is the only example we know of that was a serial disruptor, having created a string of a dozen disruptive new-growth businesses between 1950 and 1982. Hewlett-Packard did it at least twice, when it launched microprocessor-based computers and ink-jet printers. More recently, our sense is that Intuit has been actively seeking to create new-growth businesses through disruptive means. But for the vast majority of companies, disruption has been at most a one-time event.

3. We again refer readers to Robert Burgelman’s Strategy is Destiny, an extraordinarily insightful chronicle of how the ex ante and ex post quality of high-impact strategic decisions was distributed across the layers of management at Intel Corporation.

4. Practices such as “management by walking around,” which was popularized by Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman in their management classic, In Search of Excellence (New York: Warner Books, 1982) are targeted at this challenge. The hope is that by walking around, senior managers might get a sense for what the important questions are, so that they can ask for the right information needed to make good decisions.

5. Some would assert that senior-most executives still need to be involved in decisions about major expenditures because of their fiduciary responsibility not to spend more than the company has to spend. Even decisions like these, however, can be made through capable processes.

6. This account summarizes a teaching case by Clayton Christensen and Rebecca Voorheis, “Managing Innovation at Nypro, Inc. (A),” Case 9-696-061 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 1995) and “Managing Innovation at Nypro, Inc. (B),” Case 9-697-057 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 1996).

7. In our account of this history, we are using the language of our models. Lankton did not know of our research and therefore was guided by his own intuition, not our advice. His intuition was stunningly consistent with how we would have viewed the situation, however.

8. Interestingly, despite the fact that the company has missed (so far) the opportunity to catch this wave of disruptive growth in high-variety, low-volume-per-model manufacturing, the company has done very well. It has followed the pattern outlined in chapter 6 of eating its way forward from the back end, integrating forward from component manufacturing into technologically interdependent subassemblies and even final product assembly. It (very profitably) tripled its revenues to nearly $1 billion between 1997 and 2002—a period in which several major competitors failed.

9. The nature of these companies’ disruptions is analyzed in figure 2-4 and the appendix to chapter 2.

10. Something else worth noting is that we have not studied the relative success rates of founder-led versus agent-led disruptive initiatives. All we can say on the basis of the analysis we have done so far is that the relative incidence of successful founder-led disruption is higher than for agent-led disruption. Just who has a better batting average we can’t yet say. For unfortunate but understandable reasons, data on failed business creation efforts are hard to come by.

11. Clayton M. Christensen, Mark Johnson, and Darrell K. Rigby, “Foundations for Growth: How to Identify and Build Disruptive New Businesses,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2002, 22–31. We are grateful to Darrell Rigby for pointing out the possibility that an engine of growth might be created.

12. A good tool to use in this budgeting process is called aggregate project planning. Steven C. Wheelwright and Kim B. Clark described this method in their book Revolutionizing Product Development (New York: Free Press, 1992). Their concept has been extended to the corporate resource allocation process in a course note by Clayton Christensen, “Using Aggregate Project Planning to Link Strategy, Innovation, and the Resource Allocation Process,” Note 9-301-041 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2000).

13. See Rita G. McGrath and Ian MacMillan, “Discovery-Driven Planning,” Harvard Business Review, July–August 1995, 44–54.