The Basics 3

We switch here from the overarching high-level perspective of previous chapters to a discussion of the details of online tools, specialized terms, and information technology standards necessary to understand before doing business with the government. Although we don’t shirk from delving into the nitty-gritty—eventually it has to happen—we also introduce fundamental concepts of federal contracting, such as NAICS and commercial items. Our intent is to guide you through the first concrete steps you’ll have to take to start selling to the government.

Get Into the System

As we write this, the government intends to further consolidate some of the standalone systems we discuss in this chapter into a single system known as System for Award Management, or SAM.

Contractors must already go to SAM to register their business with the government and upload representations and certifications, and contracting officers use it to make sure companies or individuals haven’t been suspended or debarred from the federal market. (Each of those three functions until recently was the function of a standalone system.)

In the future, the government also intends for SAM to subsume Federal Business Opportunities (FBO) and other standalone federal acquisition websites. Whether that’ll happen on schedule as the government intends—it wants to move FBO into SAM in 2014—no one can say. The project has come under the jaundiced eye of a cost-cutting Congress that has already slowed things down through funding reductions. Still, for the systems SAM has managed to consolidate, users have the advantage of a single logon and a single back-end database that eliminates the need to rekey data multiple times. SAM is also more user-friendly than the systems it replaced; its continued development would be a good thing, just not an assured one.

Register your business

Your first step when entering the federal IT market is to notify the government of your existence via SAM. Under normal circumstances, the government refuses to award contracts to an unregistered business.1 Companies must regularly update their registration record, at the very least with an annual validation.2

Unless you specify otherwise, SAM will automatically generate a publicly searchable online record of your company. Although you can keep your entry hidden from the public, few do so, since companies themselves use these records for research into potential partners and subcontractors. SAM is as much a business tool for the private sector as a bureaucratic necessity.

As for what kind of data you’ll have to give up during the registration process, a company whose federal revenue (including subcontracts) amounts to 80 percent or more of its total, and which has at least $25 million in annual revenue, must report through registration the compensation of its five most highly compensated executives.3 And while that information won’t show up on a public SAM record, it will show up on another website, USASpending.gov.

You’ll also be asked whether during the last five years your company or its principals have been criminally convicted in connection with the award or performance of a federal contract, or whether you’ve had adverse civil or administrative proceedings against you, also in connection with a federal contract. Responses to those questions are not as straightforward as they might seem; they’re meant for publication on another public website called the Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System (FAPIIS), which we discuss later in this chapter.

Information Included in a Public Company Online Registration Record

- DUNS number

- CAGE/NCAGE

- Legal business name

- Doing business as

- Physical street address

- Type of organization (e.g., corporate entity, not federal tax exempt)

- Business type (e.g., for-profit, S corporation)

- Applicable NAICS codes

- Product Service Codes

- Federal Supply Classification

- Small business status by NAICS

- Government business primary point of contact and alternate (name, company address, telephone, and fax)

- Past performance point of primary contact and alternative (name, company address, telephone, and fax)

Get a DUNS number

Registration requires possession of a Data Universal Numbering System (DUNS) number from Dun & Bradstreet. A DUNS number is a unique nine-digit number for each physical location of your business. If you have legally distinct divisions located in the same place, each division requires its own DUNS. During registration, you can add a four-number extension to your DUNS (it’s called a DUNS+4), the extra digits pointing to a unique bank account.

Obtaining a DUNS number is free for government contractors, and Dun & Bradstreet will assign one within minutes via a dedicated toll-free number (866-705-5711) or within a day through a specific website, http://fedgov.dnb.com/webform. Dun & Bradstreet will automatically add you to its marketing list unless you opt out. The website gives you an opt-out check box; you must request an opt-out for yourself during telephone registration.4

Get a CAGE or NCAGE code

A Commercial and Government Entity (CAGE) code is a unique, location-specific five-character identifier generated by the Defense Logistics Information Service (DLIS) that’s used as a vendor identifier by the Defense Department, the Coast Guard, and NASA.

DLIS automatically generates and assigns CAGE codes to all SAM-registered U.S. companies, but foreign companies will find their registration grinding to a halt until they separately apply for a version of the CAGE code called an NCAGE—the N stands for NATO. NCAGE applicants need not be headquartered in a NATO alliance member nation, nor even in a country that has any NATO affiliation whatsoever, despite what the name might suggest. DLIS maintains Form AC/135 online for NCAGE registration.

CAGE codes, like DUNS numbers, are location-specific, which means you get one for each location registered into SAM, as well as one for each DUNS+4 registered into SAM.

Learn to speak in code

During registration, you’ll be asked to describe your business. Not in words, and not just once, but through a plethora of numbered classification systems.

NAICS

The most important, and mandatory, set of classification codes is the North American Industry Classification System, or NAICS (pronounced nakes, as one syllable). NAICS numbers are six-digit codes developed by the U.S.,

Common Information Technology NAICS 1

511210: Software publishers |

541512: Computer systems design services |

518210: Data processing, hosting, and related services |

541513: Computer facilities management services |

541511: Custom computer programming services |

541611: Administrative management and general management consulting services |

Canadian, and Mexican governments, and they describe an economic activity with increasing specificity as the digits go from left to right (see Figure 3-1). The entire six-digit number describes a particular industry, such as software publisher, which is NAICS 511210. The first two digits denote an economic sector, followed by a subsector, then an industry group, followed by the industry. The final digit is reserved in case any of the three governments using NAICS want to make a country-specific designation.

NAICS was created to organize and categorize economic activity for the purpose of facilitating statistical analysis, but acquisition policymakers latched onto the codes as a way of organizing and narrowing the bidding field by specifying that companies must have such-and-such NAICS in order to respond to a solicitation. Most companies, except the most specialized, qualify for more than one NAICS code.

The Small Business Administration (SBA), which is responsible for establishing size-standard thresholds for small businesses, does so by NAICS.5 Only companies that qualify as small according to the SBA’s definition of small per their NAICS codes can participate in opportunities set aside for small businesses. For more on size determination, see Chapter 11.

The Census Bureau subjects NAICS to potential revision every five years, and technology-related codes in particular are subject to change, thanks to the dynamic nature of the industry. The SBA has its own timeline for updating small-business thresholds. It must update one-third of its size standards every 18 months so that all size standards come under assessment in slightly under five years.

For all their seeming detail, NAICS codes are a blunt instrument for classifying what companies do. The governments behind NAICS know this, too, and have under development something called the North American Product Classification System (NAPCS). NAPCS—which classifies products and services, rather than industries—might become more common in the United States starting in the year 2017.6

Identify your PSC and FSC

Bet you thought you were done inputting codes to describe your business. Guess again—SAM has optional fields for your Product Service Code (PSC) and Federal Supply Classification (FSC) code.

PSCs classify services (despite having the word “product” in them), and FSCs classify manufactured items, including software. They are both four-character codes and, like NAICS codes, read from left to right with increasing specificity.

The presence of the word product in PSC is responsible for no small amount of mystification, as we can attest from experience. Its name is a throwback to the era before the rise of services contracting, when services mostly were rendered in support of a particular product—copy machine repair and the like.

Although optional, we recommend inputting your PSC and FSC codes. NAICS codes define categories of businesses; PSC and FSC codes denote services and goods the government consumes. NAICS codes define who you are; PSC and FSC codes indicate what you do.

PSCs

Most PSCs begin with a letter (see Figure 3-2). The exception is research and development services, which have their own set of rules (they begin with two letters).

The first letter typically identifies the category of service. For example, R is professional, administrative and management support services. The next character is a digit, which specifies the type of service within the category. R6 is administrative support services, while R7 is management support services, and so on. The final two digits indicate the specific service itself: R702 means data collection services.

FSCs

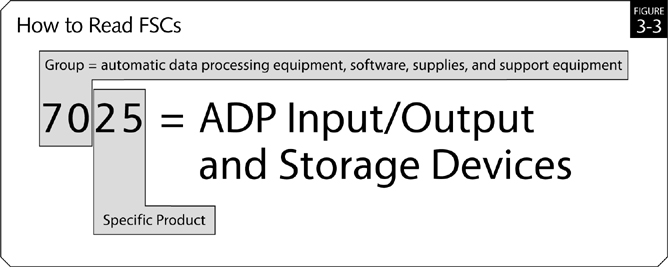

FSCs aren’t alphanumeric; rather, they consist of four digits (see Figure 3-3). The first two denote group; for example, 70 is automatic data processing equipment, software, supplies and support equipment. (Group 70 is the FSC IT category. That the IT FSC is described in 1970s-era terminology just shows how slow government is at times.) The last two FSC digits denote an actual product. For instance, 7025 is ADP input/output and storage devices.

Declare your reps and certs

Representations and certifications—reps and certs—are publicly available statements about the character of your company, such as past debarments and company ownership. It used to be that as part of every solicitation response, companies had to submit a whole pile of paper reps and certs in which they also affirmed matters such as not having employed child labor, having filed all required Equal Employment Opportunity reports, and so on. Thankfully, most of that is now done electronically through SAM. There are some reps and certs that you can elect to make on a solicitation-by-solicitation basis.

Being completely accurate and honest when filling out your reps and certs is vital, since an inaccurate response could get you charged with a felony. If you are unsure about the correct response to a question, do not give it your best guess; stop the registration process and research your answer.

Know the Rules and the Players

Before attempting to do business, you need a quick overview on how the federal IT market playing field is set and who you’ll encounter on it. Federal contracting is at first a confusing swirl of activity. Study it, and you’ll see patterns emerge, however loose and dynamic as they are.

The Federal Acquisition Regulation

Much of what goes on in contracting is structured around the Federal Acquisition Regulation, a 53-part (plus appendix) compilation of rules and advice.

Although complex, the regulation—known as the FAR—is a document of which everybody doing business with the government can, and should, gain a general awareness. At a minimum, you should know that Part 52 is where all the contract clauses—the ingredients of every government contract action—appear. If you come across a federal contracting term you’re unfamiliar with, look at Part 2, which is where all the definitions are kept. Additionally, search the table of contents of online versions to see all the places where that particular procurement concept is discussed.

The FAR’s Reach

The Federal Acquisition Regulation is chapter one of Title 48 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the set of rules that govern everything the government can do. Agency supplements make up subsequent chapters.

The only federal agencies not bound by the FAR are the CIA and the Federal Aviation Administration, which confusingly has a “FAR” of its own. In the FAA’s case, FAR stands for Federal Aviation Regulations. When we in this book talk about “the FAR,” we are talking about acquisition, not aviation.

Also exempt from the FAR are “quasi-governmental agencies,” including the U.S. Postal Service, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The Micro-Purchase Threshold

The upper limit of a micro-purchase currently is between $2,000 and $3,000, depending on whether what’s bought is a good, a service, or construction work. It’s $2,000 for building services and alterations, $2,500 for all other services, and $3,000 for supplies. During emergencies related to military operations or defense of or recovery from a weapons of mass destruction attack, you no doubt will be happy to learn that the threshold limit jumps to $15,000 inside the United States and $30,000 outside it. (FAR 2.101)

The dollar limit of what constitutes a micro-purchase is subject every five years to potential revision due to inflation. The five-year cycle occurs in years evenly divisible by five, e.g., 2015 or 2020.

Admittedly, the FAR can be frustrating because despite its 53 parts and appendix, plenty of ambiguities and gaps exist. In addition, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a congressional agency with the power to monitor agency procurements, has built up decades of decisions about agencies’ application of the FAR, precedents that are as important as the FAR itself when it comes to understanding the regulation’s finer points—which are in constant flux anyway because Congress and the White House love using the FAR to implement all manner of policy. Every one of those bright ideas precipitates 6 to 12 related changes throughout the FAR. Occasionally, some related updates are missed, and apparent inconsistencies present themselves.

Neither is the FAR the last word at most federal agencies. Federal departments pile on additional regulations in the form of agency-specific supplements. The Defense Department has the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the General Services Administration has the GSA Acquisition Regulation (GSAR), and so on. The military services—along with the Defense Logistics Agency and U.S. Special Operations Command—layer on yet another stratum of regulations through supplements specific only to themselves.

None of this is reason to avoid, or barrier to, familiarizing yourself with the FAR, which is the overarching framework for federal procurement as a whole. We’ve annotated our chapters going forward with FAR references—check the endnotes at the end of each chapter for the place in the FAR where the concepts we discuss originate. When the topics we discuss are governed by rules best cited to regulations other than the FAR, we’ll endnote those sources, too.

Contracting officers

Contracting officers exist because other federal employees are mostly prohibited from buying anything worth more than the threshold of a micro-purchase. Only contracting officers possess a certificate called a warrant, a delegation of explicit authority from the agency’s senior procurement executive that spells out to the dollar the value of contracts to which they can bind the federal government. Warrant size and scope increases with experience, education, and seniority. Remember: Only contracting officers can bind the government and obligate it to pay a bill. A commitment from any other federal employee about a new contractual relationship is vapor until and if it’s ratified by an actual contracting officer. (Some contract vehicles, once established, permit other feds to place orders against them even above the micro-purchase threshold. Usually the contract terms will specify who is so authorized.)

Because contracting officers typically deal with process rather than formulating requirements, novices often think contracting officers’ role is peripheral. That’s incorrect. Before contract award, contracting officers have power over whether a contract is let today, next quarter, or ever. They can speed things along or bog them down. In many cases, they even make the final purchase decision.

Neither do contracting officers disappear once the contract is awarded, at least not for contracts requiring services—although it’s likely that a different individual will be involved. An administrative contracting officer (ACO)—almost always a different person from the preaward contracting officer—signs contract modifications and handles oversight that can even include approval authority over subcontractors.7 (Product companies may never have to deal with an administrative contracting officer, because generally once a product is sold, the contract is fulfilled.)

Most companies also interact with contracting officer representatives (CORs), officials involved in planning big procurements and in monitoring vendor technical performance afterward. Their job is to be the eyes and ears of the procurement shop in program management; CORs can have a lot of influence over program management and the technology bought in support of a program.

Far from ignoring contracting officers, expert companies take proactive steps to see that their needs are satisfied. They also ensure a friendly but professional relationship. Don’t give or offer them anything. Contracting officers are highly sensitive to even the slightest appearance of bribe-taking by accepting something of value from a vendor, even a coffee mug with your logo on it.

Contracting officers have varying levels of experience and knowledge. It takes years to attain a thorough understanding of all the regulations, contracting mechanisms, and agency wishes.

If you come across an intractable contracting officer, don’t try to outmuscle him or her. Trying to back contracting officers into a corner makes it highly unlikely that you will be able to easily resolve the problem, even if you’re right and they’re wrong. Probe at the edges. Ask questions: how experienced is that contracting officer? Is he truly ignorant or just staking out a strong starting position for negotiations? How amenable is he to discussion of different viewpoints? If you decide to go over an officer’s head, do so diplomatically and with advance notice to the next level in the contracting officer’s chain of command.

Vendors often don’t deal directly with contracting officers, but rather with contracting specialists, who are far more numerous than the officers who supervise them. Specialists don’t possess a warrant but nonetheless do most of the legwork.

Commercial vs. noncommercial

The government officially favors buying to the greatest extent possible goods and services offered commercially—that is, something exactly like or similar to what the private sector itself consumes.8 A deprecating attitude toward commercial products still persists in some quarters of government, but government-unique requirements, such as a now-defunct mandate that Defense Department systems be coded in Ada, an obsolete computer language the Pentagon developed for itself in the late 1970s and early 1980s, are mostly a thing of the past.

Being considered a vendor of a commercial item (including commercial services, whether the services directly support a product or are standalone, such as help desk or consulting) brings with it advantages in addition to conforming to the government’s preference. Sellers of noncommercial items can be burdened with heavy cost accounting requirements, while commercial-items contracts are exempt from a bevy of regulations. For specific contrasting examples of commercial versus noncommercial contract clauses, see the section on cost accounting on pp. 77–78; fair and reasonable pricing on pp. 70–73; terminations on pp. 112–114; and contingency fees on p. 139.

So strong is this federal preference that the FAR has a loophole allowing what most objective observers would consider noncommercial items to be sold as commercial items. The magic words are “of a type” and, to a lesser extent, “nondevelopmental.”9 It’s up to contracting officers to make of-a-type determinations, and they do so case by case.

If a product is convincingly similar to goods used by the general public, or if a service likewise approximates those sold competitively in substantial quantities within the private sector, then it can gain commercial-item status. Advanced technology not yet for sale to the public but that has been developed from commercially available items, and that a company plans to sell to the public (regardless of whether it’s yet done so), can also count as an of-a-type commercial item. Even modifications to commercial items made expressly for governmental use need not disqualify a product, so long as the modifications are “minor.” Minor means modifications that do not significantly alter the nongovernmental function or essential physical characteristics of an item or component, or change the purpose of a process.

Items developed exclusively for governmental purposes—“nondevelopmental items” in federal contracting terminology—can likewise be considered as commercial items, so long as they were developed at private expense and are sold competitively in substantial quantities to state and local governments. Radio systems used by city, county, and state emergency responders are one example.

It is possible for the government to get carried away with of-a-type reasoning, as did the Air Force when in November 2002 it called a $150 million advanced communications satellite a commercial item. That and other abuses provoked Congress in 2008 to add a few restrictions. The upshot is that now, before contracting officers allow an of-a-type pass for services not actually sold in substantial quantities in the private sector, they can press contractors for financial information such as prices paid by other customers or even internal labor costs, material costs, and overhead rates.10 Contracting officers must affirm in writing that they have sufficient information to determine price reasonableness, and since written determinations make contracting officers nervous, they might be apt to demand more, rather than less, information.

Commercially available off-the-shelf products are the subset of commercial items for which there’s no of-a-type exception. If a solicitation asks for COTS, the government truly wants an item that’s really ordinarily sold and bought within the regular commercial, private-sector marketplace. To qualify as COTS, an item cannot be modified, not even in a minor manner, from the form in which it is sold in the commercial marketplace, and it must be sold in substantial quantities to private sector customers.11

Responsibility determinations and FAPIIS

Before contracting officers sign a contract, they must make a determination that the prospective vendor is a responsible one.12 They make this determination on a case-by-case basis, and a decision that a particular company isn’t responsible for one contract doesn’t automatically invalidate its chances of winning another contract. A contracting officer’s responsibility determination is different from suspension or debarment, which cuts off a company or person from competing for any federal business at all while the exclusion is in effect. We discuss suspension and debarment in Chapter 7.

What makes a contractor “responsible”—capable of delivering against a particular contract—includes adequate financial resources, being able to comply with the delivery or performance schedule, having a satisfactory past performance history as well as a record of integrity and business ethics, having the necessary organization, experience, and technical skills (or the ability to obtain them), and, if applicable, having the necessary production, technical equipment, and facilities (or, again, the ability to obtain them).13

Would-be contractors don’t always receive notice that a contracting officer thinks their company is not responsible, although there is legal precedent that if the determination is made on integrity or ethics grounds, then the government is obligated to give notice and an opportunity for the contractor to respond. (A contracting officer who believes he’s uncovered a significant integrity matter will likely elevate the matter to a suspension and debarment official, who is governed by clear rules designed to give companies due process.)

Applicants for a GSA schedule do get a notification, no matter the cause, if a contracting officer rejects their offer on nonresponsibility grounds. The notification is made in the expectation that if the applicant applies again, it’ll no longer have those faults.14

Small businesses also get a notification in the event of a negative determination, assuming the business hasn’t already been suspended or debarred. Along with that notification, small businesses receive an invitation to apply for a certificate of competency from the SBA.15 Companies that qualify for a certificate have their nonresponsibility determination overridden. Getting a certificate can take some time, but if you qualify for one, you might also qualify for participation in more extensive small business programs, such as set-asides. (Being forced to apply for a certificate of competency because a contracting officer doesn’t think your company is responsible shouldn’t be your first introduction to SBA. We cover small business issues in Chapter 11.)

Contracting officers have a single source from which they can draw contractor performance and ethics information, a database called the Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System (FAPIIS). Contracting officers must consult a company’s FAPIIS record before awarding any contract worth more than a certain threshold (the simplified acquisition threshold, which is currently $150,000—we discuss what that means in Chapter 5).16 FAPIIS data, except past performance reviews, is publicly available. If a company comes across information in FAPIIS it believes shouldn’t be in the database at all since it falls under an exemption of the Freedom of Information Act, it has seven calendar days from the date of the information’s posting to make a written objection.17 Contractors are notified when contracting officers add new information into FAPIIS. The objection is then resolved in accordance with FOIA procedures.

Companies themselves self-report into FAPIIS their, and their principals’, criminal convictions, civil judgments, and adverse administrative proceedings in connection with the award or performance of any federal contract in which there occurred a finding of fault and payment of a liability or penalty worth more than $5,000, or administrative reimbursement, restitution, or damages greater than $100,000. Administrative proceedings are nonjudicial processes including Civilian Board of Contract Appeals proceedings, Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals proceedings, and Securities and Exchange Commission administrative proceedings.

Similarly, if a criminal, civil, or administrative proceeding was disposed of by consent or compromise with an acknowledgment of fault by the contractor in a case that would have met the reporting conditions, then contractors must also report that.18 Contractors must self-report any of the above actions only when they occur in connection with the award or performance of a federal contract.19

Civil and administrative actions need be self-reported only if the company is found to be at fault, or admits fault. The regulatory language is very firm that civil and administrative proceedings must involve “fault and liability” (italics added) for inclusion in FAPIIS.20 This is significant because companies typically settle federal civil and administrative cases without acknowledging fault.

Whether the fault requirement will remain in place for civil and administrative proceedings in the near future is uncertain; it’s certainly possible that Congress could remove it. Other changes to FAPIIS under consideration by Congress include lowering the threshold for actions that trigger FAPIIS reporting from $500,000 to the simplified acquisition threshold and requiring companies to self-report violation of other laws, not just violations in the context of federal contracts. In short, stay tuned.

Company self-reporting to FAPIIS is done through SAM. Companies with more than $10 million of annual federal business must affirm in response to any solicitation potentially worth more than $500,000 that the information meant for inclusion in FAPIIS (via SAM) is up-to-date.21 Such companies bidding on such solicitations that then win an award must thereafter update FAPIIS information through SAM semiannually throughout the life of the contract.22 FAPIIS data remains available to contracting officers for five years after its entry—and some in Congress want to expand that to a decade. The FAR says contracting officers must use “sound judgment in determining the weight and relevance” of FAPIIS information, whatever that means.23 Some people think serving blood sausage shows sound judgment.

Companies can attempt to mitigate FAPIIS information about them by explaining their side of the story to contracting officers, who must request additional information from contractors whenever they encounter information in FAPIIS relevant to a responsibility determination.24 Contractors have always been permitted to attach comments and additional information to an agency past performance evaluation, so long as they do it within 30 days of receiving one.25

Start Prospecting

After you’ve keyed yourself into the government databases, the government officially will do business with you. But just as it was your job to inform the government of your presence, it’s your job to find opportunities and land contracts. This is no simple task, and much of this book is dedicated to describing how to do so. This section, then, describes just very basic points. It’s merely a start, the place where everyone begins.

Learn to navigate FBO

Despite its name, FBO doesn’t exclusively contain standalone opportunity notices. The procurement process generates a lot of records, many of which land on FBO, and many of which contain useful information. As we noted at the start of this chapter, FBO is a system slated for merger into SAM in 2014, although it’s uncertain whether the government will have the money to do so. Regardless, the functionality we describe should remain much the same whether FBO remains a standalone system or becomes part of a larger one.

Criteria by Which FBO Searches Can Be Narrowed

| Keywords | Place of performance ZIP Code |

| Opportunity/procurement type | Set-aside code |

| Posting date | Classification code |

| Response deadline | NAICS |

| Last modified date | Agency/office(s) |

Using FBO requires a period of getting accustomed to its quirks. FBO is a crowded, messy place where multibillion-dollar solicitations for advanced technology lie side by side with requests for quotes for wooden shipping pallets.

Luckily, records are searchable by NAICS and a variety of other terms, including classification codes, which are FSC and PSC designations at their broadest—that is, the first two digits of FSCs and the first letter of PSCs. You can also narrow searches by record type.

The search engine accepts Boolean terms, defaulting to or searches—that is, returning back any record that contains even just one keyword. Use and to exclude results that contain only one term when doing searches with multiple keywords. Multiple words surrounded by quotes are treated as a single search term, as in “information technology.” Search mavens can do wildcard, fuzzy, and proximity searches. FBO is also open to web crawlers, leaving the door open to searching via Google with the limiter “site:fbo.gov” after your search term.

Users can also create accounts from which they can set up watch lists, create and save search criteria, run those searches automatically, and respond electronically with quotes or proposals, if the contracting agency is set up for it. Anybody can set up an account, but businesses registering with a DUNS number get access to controlled (but still unclassified) data. FBO contains no classified data unless something slips through by accident, which has happened.

Actual solicitations posted on FBO fall under the category of Combined Synopsis/Solicitation. The category name alludes to a federal law requiring that agencies synopsize the goods or services they want to acquire in the same document as a solicitation. Solicitations themselves often take the form of a request for proposals (RFP) or request for quotes (RFQ), but FBO doesn’t categorize solicitation type according to contracting method.

National Stock Numbers

FBO solicitations sometimes make reference to a national stock number, or NSN.

An NSN is a 13-digit code assigned by the Defense Logistics Information Service to a product repeatedly bought by federal agencies—mostly, but not absolutely, by the Defense Department. Some NSNs describe products manufactured by only one company, while others are commonly made items. Only the military or federal agencies can request a product be assigned an NSN, and they’re given only to products.

The first four digits of an NSN indicate the FSC category the item falls into.

Confusingly, you sometimes might also see a reference to a national item identification number (NIIN). Not to worry: an NIIN is just an NSN minus the FSC—nine digits instead of 13.

Occasionally you might see a solicitation going by an esoteric, agency-specific name. NASA, for example, calls a solicitation that involves sending experimental hardware into space an Announcement of Opportunity.

Notices of future procurements—perhaps the most important type of record you’ll find on FBO—fall under the categories of Presolicitation, Sources Sought, or Special Notice.

The types of records placed under those categories include draft RFPs, requests for information (RFIs), or sources sought notices (SSNs).

Agencies typically issue RFIs when they’re considering a complex procurement about 12 to 18 months later but aren’t quite sure what they should buy and so canvass for private-sector feedback. SSNs crop up when the government has a tighter handle on its requirements and wants to test the market waters for potential bidders, particularly small businesses. If two or more small businesses respond to a SSN, the agency will often make the anticipated procurement a set-aside in order to meet its socioeconomic contracting goals.

Draft RFPs are a final prelude to an actual solicitation. Agencies issue them in an effort to gain feedback on weak points and so remove anything that could later cause the procurement to be delayed, such as a protest filed over uncertain requirements or unclear evaluation criteria.

Both RFIs and SSNs usually contain language stating that they are for “planning purposes,” and that a response “does not obligate the government.” While that’s true, and it’s also true that not every RFI becomes a procurement, participating in the presolicitation process is a key activity that leads to contract actions. It’s foolish, even, not to respond, particularly to RFIs, or if you’re a small business, to SSNs.

Contracting officers sometimes also assign the Sources Sought category type to Broad Agency Announcements, which are solicitations for scientific studies and development, and to industry day notices. Industry days are government events at which agencies communicate their procurement plans—meetings you should plan to attend.

Also dumped into the Presolicitation category are notices that the government intends to award without competition a contract to a company for a particular product or service. Such notices, despite their air of finality, are called presolicitations because when the government posts such a notice on FBO, it hasn’t yet bought the item. It merely wants and intends to buy it, probably within the next 30 days. As such, you can interpret such presolicitations as highly veiled calls for a competitor company to come forward with something better. If federal officials don’t hear a peep of challenge after posting the presolicitation, they make the award and note in the procurement file that the notice garnered no response.

An actual procurement made without competition generates a “justification and approval” record that’s also posted to FBO under a category of the same name.

Search agencies’ websites

The FAR says agencies must post notice to FBO of every planned federal acquisition expected to result in a standalone contract valued at more than $25,000, but the truth is that what ends up on it sometimes is nondescript and sparse, and might appear a day or two later than the more detailed record found on agency-specific procurement websites roughly duplicative of FBO.

The worst offenders, it should come as no surprise, are military services—not necessarily because they’re trying to discourage outsiders, but mainly because they’re big organizations and accustomed to doing things their way.

Thus, the Army has the Army Single Face to Industry (ASFI) website, and the Department of the Navy its Navy Electronic Commerce Online (NECO) site. Also, the Defense Logistics Agency has the DLA Internet Bid Board System (DIBBS). The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) hosts the Acquisition Research Center for its and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency procurements, but limits access to registered firms with sufficient clearances. Other intelligence agencies could start using the NRO’s system, as well.

Opportunities worth less than $25,000

So what about standalone contract opportunities not valuable enough for inclusion in FBO? Here’s what’s happens:

• Notice of an opportunity worth more than $15,000 but less than $25,000 must be posted so local vendors can see it. This often means a paper notice tacked onto a publicly accessible “bid board” in a federal building.26

• The FAR is silent on how federal agencies should handle opportunities worth between $3,000 and $15,000, but the typical practice is for contracting officers to solicit three oral quotes from local businesses—no public posting of the opportunity required—particularly if the requirement is for commercial items.27

• Any purchase worth $3,000 or less is simply made with a government-issued credit card. At some point paperwork costs more than it’s worth; for federal agencies, that point is any single transaction worth up to $3,000.

Going after business at this level without a contract vehicle is only worth your while if you’re a small business, since government policy reserves any contract for commercial items worth between $3,000 and $150,000 for small businesses.28

Federal purchases worth less than $3,000 are mostly for workaday stuff. More likely than not, the government will pay for these transactions using government-issued charge cards called SmartPay, which is the official preferred payment method for purchases under the micro-purchase threshold.29

Any business that already accepts Visa and MasterCard can accept a government charge card—there’s nothing special to it. A SmartPay sale is just another plastic card transaction. Certain merchants are blocked from SmartPay transactions, but unless your company is an escort service, a pawn shop, a casino, or some other business so obviously removed from federal work needs, there’s nothing to worry about.

Consider Getting a GSA Schedule Contract

The General Service Administration schedules are multiple-award contract vehicles that create a catalog of government-approved price listings of commercial products or services with prenegotiated terms and conditions from which any federal agency can place an order. State and local governments can buy information technology through GSA schedules, too. The Department of Veterans Affairs, with the permission of GSA, manages a set of schedules covering medical equipment and supplies. But for the most part, if you hear people (or us) talk about “the schedules,” they’re talking about GSA schedules.

The of-a-type commercial-item hedging we noted earlier in this chapter applies to schedules, too—but the trend of the past few years has been to permit it for services more than products. A services company in possession of nothing but a past performance record from federal clients will probably get a schedule, whereas a similar products company likely will need to find private-sector customers before being awarded a contract.

GSA posts schedule prices on GSA Advantage, which is an online ordering system for feds, akin to Amazon.com. GSA also runs an e-procurement system called eBuy, which allows agency contracting officers to electronically gather quotes from schedule holders only. A schedule can also gain you admittance to eMall, the Defense Department equivalent of GSA Advantage. Schedule-based RFQs need not be posted on FBO regardless of potential order size, since only standalone procurements need to be posted there, and the government doesn’t consider schedule purchases to be standalone.

But a schedule is not a golden ticket. Possession of one doesn’t guarantee you any government business—it’s merely, as you’ll hear in an oft-repeated line, a license to hunt for federal customers. Moreover, getting one has heavy implications for the prices your company can charge to nongovernmental customers. If you’re not careful, you might find yourself in a downward price spiral affecting your commercial and government prices.

It’s perfectly possible for product companies to start doing business in the federal IT market without a schedule contract, although services companies might find that not to be equally true for them. Still, applying for a schedule is no light decision. We go into depth about schedules in Chapter 10.

GSA schedule holders must accept SmartPay for purchases made under the micro-purchase threshold, but if you’re selling things at that price point, chances are good you accept credit cards already. You can elect to accept SmartPay for transactions worth more than the threshold—but as a word of warning, if you routinely offer a prompt payment discount to government as a condition of your schedule, the discount, plus the credit card transaction fee, can eat away a major part of the slim margins allowed on these contracts.

Get Paid

Ultimately there will come the day when the government owes you money for services rendered or goods delivered and accepted.

The good thing about doing business with the government is it always pays—even if it’s sometimes a little slow in doing so. Of course, making sure you are paid requires the same level of attention to miniscule details that’s been required of you in order to get here in the first place.

To start with, the government will reject invoices it does not consider to be “proper.” The main challenge to issuing a proper invoice is matching the services or goods provided to the contract line items (CLINs) in your contract.

Payment lives and dies by CLINs. If you deliver or do something not called for in the CLINs, it’s on the house. But even a company careful to provide no unplanned freebies can still, at the moment of invoicing, struggle to match goods and services provided to an exact CLIN. In such cases, contact the contracting officer to get things squared up before submitting the invoice.

As for how exactly to submit those invoices, the answer varies according to the agency. The Defense Department has an advanced electronic invoice submission system called the Wide Area Workflow (WAWF). Further, the Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS) has a system called myInvoice that lets contractors check invoice status online.

Other agencies have invoice systems of their own, too, with varying levels of functionality—some agencies compel absurdities such as requiring you to submit an electronic and a paper invoice. Other agencies simply have you fill out a PDF document and email it to the contracting officer.

After submitting a proper invoice for goods or services, a law called the Prompt Payment Act theoretically obliges the government to respond with money within 30 days.30 Should the government take longer, it’s supposed to pay interest.

In reality, you’re doing quite well if you receive payment between the 40th and 50th day after submitting the invoice, and collection of interest payments is very rare.

The 30-day clock, you see, doesn’t ordinarily start ticking at the earliest until after seven days have passed from the date on which the goods were delivered or the services completed.31 Also, if the 30th day happens to fall on a weekend or holiday, payment can occur without penalty on the next business day.

And, should the government deem an invoice to be improper, things take even longer, since the clock doesn’t start counting down until receipt of a proper invoice. Contracting officers have seven days from receipt of the invoice to determine whether it’s proper or not. Only if they fail to inform a vendor of the invoice’s improperness within that time does the 30-day clock start, and even then only the days between the seventh day and the actual date of notification count toward the 30-day period.

If you don’t hear back from a contracting officer within seven days of submitting your invoice, contact him or her to ensure that things are proceeding as they should.

A word of warning on what happens should the government make an accounting mistake and pay you more than intended: while holding onto an unexpected windfall might be tempting, contractors should notify the government immediately about the extra money and make ready to refund the balance. Failure to return the extra dollars can easily result in the government banning your company, and you personally, from doing business with it.

Final Note

Now you have the minimal amount of information you need to start trading with federal agencies. If you’re completely new to the federal market, we highly recommend you continue reading. Although we’ve called this chapter “The Basics,” just about everything in this book constitutes basic knowledge.

ENDNOTES

1. Registration is absolutely necessary, except for a contract awarded during the course of military or emergency operations, under unusual and compellingly urgent circumstances, when registration would compromise classified information or national security, or if you’re a foreign vendor performing work done outside the United States and registration would be impractical (think war zones and natural disasters). Also, registration is not necessary for companies whose only interaction with the government as a customer is via federal charge card. The convenience store down the road from a federal plaza or military base need not bother to register.

2. FAR 4.1105 and 52.204-7(f).

3. FAR 4.1403(a) and 52.204-10(c)(2).

4. There is some talk within government of eliminating the DUNS requirement in favor of a government-generated unique identifier for vendors. Keeping the DUNS service free for government contractors and grantees costs the government $18 million a year. However, DUNS numbers are so deeply embedded into federal financial systems that their removal couldn’t happen overnight.

5. Of the 1,173 NAICS codes that exist today, 17 have more than one size threshold in order to accommodate different types of businesses. For example, 541519, other computer related services, has a revenue threshold for most businesses. But information technology value-added resellers, which are classified as falling under that NAICS, are measured by number of employees, not by revenue.

6. The Census Bureau conducts an economic census in years ending in 2 and 7.

7. FAR 44.202-1(a).

8. Procurement rules for commercial items are in FAR Part 12.

9. FAR 2.101.

10. FAR 15.403-1(c)(3).

11. FAR 2.101.

12. FAR 9.103(b).

13. FAR 9.104-1.

14. GSA Acquisition Manual 509.105-2(a).

15. FAR 9.103(b) and 19.6.

16. FAR 9.104-6(a).

17. FAR 52.209-9(c)

18. FAR 9.104-7(c) and 52.209-7(c).

19. FAR 9.104-7(b) and 52.209-7(c).

20. Regarding fault and liability, FAR 52.209-7(c) says that contractors must self-report whether they have been in a civil or administrative proceeding that results in “a finding of fault and liability.”

21. FAR 9.104-7(b) and 52.209-7(c).

22. FAR 9.104-7(c) and 52.209-8.

23. FAR 9.104-6(b).

24. FAR 9.104-3(c).

25. FAR 42.1503(b).

26. FAR 5.101(a).

27. FAR 13.106-1(c).

28. FAR 13.003(b)(1).

29. FAR 13.201(b).

30. The payment time frame for agricultural products is shorter. Also, the Prompt Payment Act does not apply to the U.S. Postal Service. The act is implemented by FAR 32.9.

31. 5 CFR 1315.4(b).