The Best Relationships Are 5

Based on Contracts

How the government chooses what it buys is often not a function of what’s best, but of how easily it can be bought. “There were a lot of times we won business simply because we were on the right contract vehicle and our software was good enough,” one salesman told us.

The contractual process in the federal government isn’t a mere means to an end. The process influences outcomes, and companies can be battered or buoyed by it depending on their understanding of the mechanics involved.

We’ve dedicated this entire chapter to the fundamentals of government contracting. Make no mistake—although it’s on the technical side, without this knowledge, winning information technology business from the government will be tough.

Contracting Methods

A constant tension exists in government contracting between getting things done quickly and ensuring the widest competition possible. The government strives simultaneously for both, and the result is a convoluted arrangement that seeks to reconcile the irreconcilable.

The most visible expression of the tug of war between the desire for speedy decisions and the legal requirement for a competitive process is in the method by which the government contracts. Contracting method is the manner in which government invites and evaluates vendor quotes or proposals. It can choose from many different methods, each with its own parameters of competition and expeditiousness.

If the federal market is like a playing field, then the field’s length varies from procurement to procurement. In sports, this would be sacrilege, but running the federal government isn’t a game. Federal agencies make use of different contracting methods—that is, they alter the playing field—to suit their needs. Procurements that have the greatest effect on agency missions tend toward rigorous openness and prolonged evaluation, since the benefits of observable competition outweigh speed in those cases.

Still, what looks good on paper doesn’t always pan out. As we shall see, the most putatively competitive contracting method of them all is actually a recipe for stagnation. We tackle contracting methods here in general order of apparent competitiveness, starting with the most competitive and ending with the most limited.

Sealed bidding

In theory, the most competitive contracting method is also the oldest: sealed bidding.1 Before 1984, when Congress introduced much-needed reform, sealed bidding was the norm.2 State governments still resort to it fairly often.

Sealed bidding works like this: With no prior input from industry, agencies describe exactly what they want to buy in a document called an invitation for bid (IFB). Companies submit secret bids to provide it. The award goes to the company considered the “lowest responsive, responsible bidder.” Responsive because the bid conforms exactly to specifications, and responsible because the government makes a determination that the winning company can deliver on its offer. Anybody who proposes to deliver items that differ even slightly from the spec is disqualified from the competition, no matter how much better that alternative may be.

Although it’s unbearably stifling, this method does seem to encourage cutthroat competition, since companies race to cut prices to become the lowest bidder. In reality, the history of sealed bidding in IT is one of monopoly, because in the era in which it prevailed, federal agencies designed the specs to match a particular company’s technology. IBM dominated much of the federal mainframe market in this way.

Reverse auctions

Old-school sealed bidding is rare today within the federal government for IT procurements, but it lives on in mutated form: online reverse auctions, in which companies publicly underbid each other, the lowest bidder again winning the contract.3 When one company objected in 2005 to the Government Accountability Office (GAO) that reverse auctions shouldn’t be allowed because the method requires companies to reveal pricing information where competitors can see it, the GAO in effect replied “tough,” because participation is voluntary and public disclosure is a condition for entering the competition.4

But—for the same reasons that sealed bidding lost favor—reverse auctions have yet to capture a significant portion of federal IT contracting. Reverse auctions are a method for buying commodity items, often small quantities of brand-specific part numbers. A handful of agencies use them to conduct quarterly or semi-annual procurements of products from approved vendors for pre-defined configurations and quantities of office machines such as desktops, laptops, and printers, but few manage to have the discipline necessary to aggregate requirements like that.

Negotiated procurement, a.k.a. RFPs

Contracting by negotiation is the underlying premise of a solicitation issued in the form of a request for proposals (RFP).5 Negotiated procurement, so called because after companies submit proposals, federal source selection teams can ask for clarification and hold discussions with companies, isn’t much less competitive than sealed bidding. Like sealed bidding, it’s full and open in the sense that anybody can jump into the competition and participate. We’re qualifying it as apparently slightly less price-competitive than sealed bidding because award may hinge on factors other than price, giving an advantage to companies that understand the wider context and intent of the procurement. Also, especially in large procurements, agencies can exclude companies from the final round of consideration based on the quality of companies’ proposals, whereas the point of sealed bidding is to relentlessly, and simplistically, examine every bid for the absolutely lowest price.

Negotiated procurement is a more sophisticated acquisition tool than sealed bidding. Unlike an IFB, RFPs solicit good ideas, and price alone need not determine who wins (see the section on evaluation criteria later in this chapter). RFPs’ great advantage is flexibility, for both the private and public sectors. The disadvantage is that they often lead to a protracted and expensive engagement without certainty of consummation.

Proposal writing is as much an art as a science—although, as a rule of thumb, no one ever went wrong by mirroring the language of the solicitation in their proposal. If the RFP requests “innovative solutions,” your company’s proposal should state in as many words that “this is an innovative solution.” Those who know better than to equate real innovation with the mere appearance of the word on paper will excuse this behavior. Those who don’t, will need the reassurance. Whatever buzzwords the RFP makes use of, use them yourself, too.

RFPs for big procurements are usually preceded by requests for information (RFIs). Really big negotiated procurements are also heralded by industry days, draft RFPs, and possibly one-on-one meetings with the program office.

In preparing an RFP, the government crafts a statement of work (SOW) or a statement of objectives (SOO). The difference between the two is meant to be a vast philosophical crevasse, even though in reality the difference is often just semantics (see the discussion of both types in the next section).

RFPs hit the street in a standard format with a lot of boilerplate written into them. Reading them start to finish is mind numbing, and unnecessary. The most important sections are as follows:

• Section C: The requirements. If the SOW or SOO is lengthy, then the requirements will be an attachment. Section J lists all attachments.

• Section B: A listing of all supplies, data, and services or tasks the government wants to accomplish in support of what the SOW or SOO describes. The items listed in Section B are called contract line item numbers (CLINs). The government expects vendors to invoice according to CLIN.

• Section M: The evaluation criteria.

In addition, make sure to follow the instructions in Section L, since if you don’t structure your proposal according to them, your proposal may get tossed out as nonresponsive.

Proposals are legally binding, unless formally withdrawn before award. If the government selects your proposal for contract award, you are now legally required to provide what you said you would at the prices you proposed in accordance with the terms of the RFP.6 The government won’t consider company modifications to already submitted proposals unless the proposals are already “otherwise successful” and offer better terms to the government.7

If you submit a proposal electronically, it’s a good idea to do so by 5 p.m. one working day before the official deadline. The reason is that should your proposal somehow subsequently not make it to the correct hands by the deadline, having submitted it early will prevent procurement staff from branding your proposal as late.8

If the government intends to hold discussions after the receipt of all proposals, it will establish something called the competitive range of offers.9 Companies outside the competitive range are excluded from further consideration and aren’t invited in for discussion. Excluded companies receive notification of their elimination.10

During discussions, the government might ask for revisions in pricing—downward revisions, naturally. The government will never give a counterproposal; it can only request new prices and accept or reject them.

If asked for revisions, companies ultimately submit a final proposal revision (FPR). You might hear the term best and final offer, or its acronym, BAFO (pronounced ba-fo), which once was a technical phrase but these days lives on merely as contracting vernacular.

If you lose a negotiated procurement, whether by being excluded from the competitive range or after discussions, there are two things to keep in mind. The first is that you are entitled to a debrief, and you should request one. You want to hear why your proposal lost; it’s a learning experience, and you will likely come out better prepared for future opportunities with that agency. The second is that you might want to protest your loss, but only if you can demonstrate that the agency prejudiced your chances to win.

SOWs and SOOs—two procurement philosophies

A statement of work is much as it sounds—a description of what the government requires and what constitutes its completion. Although less prescriptive than sealed bidding specifications, SOWs still can be highly specific and preclude innovation if they focus heavily on methodology.

The government is most comfortable with SOWs. Still, worried about missing out on inventive solutions and under private sector criticism that the government was stifling its ability to be innovative and competitive, procurement officials during the 1990s came up with performance-based acquisition (PBA). Under PBA, agencies write a statement of objectives rather than an SOW. SOOs are meant to cure agencies’ tendency to define the work rather than the desired end state, or results. PBA encourages procurement officials to describe goals and performance objectives rather than how the work is to be done. Some proponents liken it to a mindset rather than a mere contracting method.

Based on the SOO, either the government or vendors craft a performance work statement (PWS), which lists tasks, but not the methods, that the contractor will undertake to fulfill those goals. To ensure task work is done according to expectation, agencies fashion a quality assurance plan (QASP) that describes metrics the government will use to evaluate contractor performance. QASPs encourage good performance by offering incentive payments for meeting targets. PBA is officially the preferred method for acquiring services.11

As a way of delivering innovation, or even just getting work on a contract, the performance of PBA has been mixed. Some vendors have taken advantage of loosely defined requirements to deliver second-rate results, while other companies have been overwhelmed by unanticipated tasks more complex and costly than described in the PWS. Successful cases do exist, but few deny that there’s a lot of confusion about how to let and manage PBA contracts, despite its decades-long existence.

Further, pressure from the Office of Management and Budget to use PBA more often has led agencies to frequently dress up SOWs with PBA jargon and call them SOOs under the “if it quacks like a duck, it must be a duck” theory. For example, a 2008 review by the GAO of 138 so-called performance-based services contracts at the Homeland Security Department found that about half of them lacked elements such as a PWS, measurable performance standards, or a QASP.12

Any SOO that refers to performance criteria for a particular technology is a clear example of a fake PBA, because true PBA by definition eschews definitions of methodology. Under PBA, a federal agency shouldn’t specify particular technologies at all; it should instead describe what it wants to achieve and let companies come up with the best technology solution.

However, no one is excused from participating in the game of false PBA, not even if they know better. If the RFP claims against all evidence that an acquisition is PBA, among the first words of a vendor’s response should be, “This is a performance-based proposal….” Evaluation teams subtract no points for obviousness nor for gratifying their pretenses.

Simplified acquisition

Negotiated procurements are all well and good, but they’re drawn-out affairs. Technology goes through at least one cycle of Moore’s law by the time an average negotiated procurement concludes. That’s why federal agencies can use yet another contracting method—simplified acquisition.13

It’s called simplified for a few key reasons. The amount of work the government must undertake to solicit and evaluate offers is much less than with negotiated procurements. Agencies need not bother with formal evaluation plans, establishing a competitive range, conducting discussions, or scoring offers.14 Also, a contracting officer, not necessarily a source selection team, can choose the contract winner.

Because source selection is less arduous under simplified acquisition, the dollar value of contracts allowable under simplified acquisition theoretically is capped at $150,000.15 But under a pilot program that Congress has annually extended since it came into being as part of the Federal Acquisitions Streamlining Act of 1994, simplified acquisition procedures can be used in procurements worth up to $6.5 million,16 provided that a contracting officer “reasonably expects” based on market research that offers will include only commercial items not worth more than that.17

Congress forgot in 2011 to reauthorize the pilot for 2012, leading to its suspension. As of this writing in mid-2012, it’s uncertain whether it’ll be restored. To see whether simplified acquisition procedures are possible for amounts greater than the threshold are still possible, consult the relevant section of the regulations, which is FAR 13.500.

For contracting officers, the distinction between procurements made through simplified acquisition procedures versus procurements under the threshold mainly has mattered because procurements above the threshold that are done using the procedures might be subject to scrutiny that acquisitions made under the threshold aren’t. For example, contracting officers must check the Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System (FAPIIS) for any procurement worth more than the threshold, but not for procurements worth less. Also, simplified acquisitions worth between the micro-purchase threshold and the simplified acquisition threshold must be awarded to the maximum extent possible to small businesses.18

In a simplified acquisition, the government issues a request for quotes (RFQ) rather than a request for proposals. The first and most important thing to know about a quote is that it is not legally binding.19 Quotes are purely informational. Transactions made under simplified acquisition procedures (above and below the threshold) become legally binding only when a company accepts an order the government makes based on a quote. Companies can only accept or reject orders; there is no negotiation.

As a result, be careful to include the terms and conditions under which you’re prepared to provide the goods or services. Remember, there’s no negotiating when it comes to orders from quotes, merely acceptance or rejection. If the government issues an order based on a quote, it’s too late to attempt to add in additional terms and conditions. However, If the order does not reflect the terms of the quote you submitted, companies can ask the government to amend the order to conform to the quote, and usually the government complies, albeit grudgingly.

A few years ago, Serena Software submitted a quote under the condition that the stated pricing was valid until only the end of June 2003. When in September 2003, the soliciting agency made an offer based on the discount, Serena was faced with either accepting or declining a government offer based on its original, supposedly time-limited pricing. Serena accepted.

As a side note, Serena competitor Computer Associates blew a gasket when it found out. It protested to the GAO on the grounds that the order couldn’t be valid because under the quote’s own terms, the price was no longer valid.20 GAO then lectured CA in writing, saying that a quotation “is not a submission for acceptance by the government to form a binding contract; rather, vendor quotations are purely informational,” and therefore it was up to the company whether or not to accept the offer, even if it was based on putatively time-limited pricing.

Other than full and open competition

People tend to call this method sole source, although in fact there are seven circumstances that allow a contracting officer to buy something worth more than the micro-purchase threshold without a competitive process.21 Technically, sole source is only one of those seven—when there exists “only one responsible source and no other supplies or services will satisfy agency requirements.”

Companies tend to salivate at the prospect of a contract made without competition, and some old-timey consultants will suggest you seriously push for it. These days, that’s not great advice. Congress hates no-competition contracts.

Seven Circumstances Allowing the Government to Avoid Competition

1. Only one responsible source and no other supplies or services will satisfy agency requirements (FAR 6.302-1)

2. Unusual and compelling urgency (FAR 6.302-2)

3. Industrial mobilization; engineering, developmental, or research capability; or expert services (FAR 6.302-3)

4. International agreement (FAR 6.302-4)

5. Authorized or required by statute (FAR 6.302-5)

6. National security (FAR 6.302-6)

7. Public interest (FAR 6.302-7)

Their use is tracked and reported, and the long-term trend is against overusing them.

There are plenty of ways to influence the acquisition process during the market research and requirements writing phases of acquisition planning so that you can win competitively on your merits. Trying to gain business by pushing for noncompetitive contracts is a ham-fisted way to go about it.

Evaluation Criteria

When the government moved away from sealed bidding, it needed a new way of evaluating proposals besides just looking at price and adhering to a spec. Finding evaluation criteria superior to sealed bidding’s lowest responsive, responsible bidder arguably was the reason in the first place for the procurement reform efforts of the early 1980s.

Hence, the best value continuum.22 At the two ends of the continuum lie opposite methods of evaluation. On one side is lowest price, technically acceptable (LPTA). This criterion, with its emphasis on price, has much in common with lowest responsive, responsible bidder. But it has the substantive difference of allowing the government to negotiate with prospective vendors, a deeply illegal activity under sealed bidding law.

On the other end of the continuum is the tradeoff process, so named because it allows variables such as technical approach to outweigh price. In the tradeoff process, the lowest bidder doesn’t automatically win. Other evaluation factors can include past performance, technical excellence, management capability, personnel qualifications, prior experience, and adherence to solicitation requirements.23 Still, the tradeoff process doesn’t exclude price as the ultimate deciding factor. If all the offerors are otherwise equal, price will break the tie. And, in the absence of any information about why one approach is technically superior, tradeoff in practice turns into LPTA.

Price might anyhow be the overriding evaluation factor, because the relative weight other variables have in a source selection varies by individual solicitation. So although a particular solicitation may claim that the tradeoff process will be used, the government may in reality favor the LPTA in all but name.

Most of the nuances discussed in this section apply to negotiated procurements rather than other methods. As noted in the simplified acquisition section earlier, one of the reasons simplified acquisition is relatively simple is that the evaluation process is less onerous than in negotiated procurement. As a result, best value applies in a less comprehensive fashion to simplified acquisitions. The FAR allows contracting officers to make the contract award decision in a simplified acquisition and to do so with great discretion. A contracting officer’s professional knowledge and experience with a good or service can be sufficient as an evaluation criterion.24 Contracting officers needn’t even tell companies the relative importance of each evaluation factor when issuing an RFQ.25

Fair and Reasonable Pricing

The FAR requires contracting officers, prior to signing most contracts, to establish whether or not the price is “fair and reasonable.”26

Under some circumstances, a simple affirmation by a contracting officer is all that’s necessary. Specifically, it is sufficient when in a simplified acquisition only one offer is received, but the contracting officer has personal knowledge about the item being purchased.27 Under other conditions, if the contracting officer states that “adequate price competition” exists and does a standard price analysis, then that’s enough, too. Adequate price competition exists when at least two companies compete independently.28 Should only one company respond to a solicitation, competition is considered to exist in civilian procurements if the contracting officer believes that the single company’s quote or proposal was based on the expectation of competition.29 A price analysis is pretty much what it sounds like: a comparison of the offered price to historical prices paid for the same or similar items.30 Matters become considerably more complex should the government demand certified “cost-or-pricing data,” which it can do at will for solicitations valued at $700,000 or more.31

The $700,000 threshold comes from a half-century-old law called the Truth in Negotiations Act (TINA) and is subject to revision for inflation every five years in years evenly divisible by five.32

Don’t let the or in “cost-or-pricing data” fool you—if the government requests it, it’s calling for “all facts that … affect price negotiations significantly.”33 Essentially, it’s all of the information companies use to establish price, meaning cost and markup.

What counts as a cost, according to the government, undergoes two tests—first, it must be “reasonable,” and second, it must be “allowable.” The rules controlling both concepts appear in FAR 31, which is dedicated to cost principles and procedures. We discuss them both further in the section on cost-reimbursement contracts later in this chapter. For now, we’ll simply note that government cost principles are mostly foreign to the private sector and that pursuing an opportunity that requires certified cost-or-pricing data could require investing in specialized government accounting software and services.

Certified cost-or-pricing data also carries with it legal consequences; contractors must declare that the data is “accurate, complete and current.”34 If a government auditor finds errors in the data, no matter how unintentional they might be, the finding almost certainly will lead to price reductions, interest payments, and possible fines.35 The government has a right to audit cost-or-pricing data for three years after the date of final payment.36

There’s a lot of confusion about what constitutes defective pricing—it doesn’t occur just because actual costs turn out to be less than the certified amounts. Cost-or-pricing data is not an estimate of contract price, but rather the factual basis contractors use to make an estimate. If a contractor knows in advance it could get cheaper supplies than for the cost amount it certified, that’s defective pricing. If a contractor manages, postaward, to lower costs thanks to a better deal with suppliers, that’s business. The regulations clearly state that certification “does not constitute a representation as to the accuracy of the contractor’s judgment on the estimate of future costs or projections.”37

Luckily, the FAR discourages contracting officers from requesting certified cost-or-pricing data, even going so far as to mostly prohibit its use for price reasonableness determinations in the acquisition of commercial items.38 Discourages, but doesn’t entirely prevent. A contractual modification to commercial-item acquisitions could trigger a cost-or-pricing data dump requirement even if the original contract price wasn’t set on the basis of certified data. Any modification worth the TINA threshold or more to a contract made via a negotiated procurement requires the contractor to prepare certified cost-or-pricing data when submitting an adjustment claim.39 A reduction in price, for purposes of this particular trigger, is counted as an absolute number, meaning that should a decrease and an increase occur for a related cause, and the combined absolute values of the modifications add up to the TINA threshold, then the contractor must provide cost-or-pricing data.40 In the Defense Department (DoD), NASA, and Coast Guard, regardless of contract method, the modification trigger mandating cost-or-pricing data on commercial contracts is the TINA threshold, or 5 percent of the contract’s total price, whichever amount is greater.41

As painful as it seems to provide cost-or-pricing data, the real hurt happens when contracting offices ask for “data other than certified cost-or-pricing data” to make a fair price determination—because they’re prone to asking for that more often than certified data. A contracting officer asking for data-other-than can require companies to submit “pricing data, cost data, and judgmental information … [including] the identical types of data as certified cost or pricing data.”42

Companies can give thanks that at least they needn’t under this circumstance certify the data—and so circumvent the auditing and legal ugliness of a potential defective pricing charge. But that’s a little like being glad that a minor hurricane isn’t a major one. Although contracting officers probably won’t require data-other-than to be quite as detailed as certified data, the request is nonetheless going to feel invasive.

If confronted with a data-other-than request, there’s no legal requirement that you must comply. However, companies that refuse to go along are ineligible for the contract award, unless the agency’s senior contracting official makes a highly unlikely exception.43

According to the FAR, contracting officers should generally refrain from asking for data-other-than (regardless of whether the item in question is a commercial item or not) whenever adequate price competition exists.44 This is a restraint not always heeded.

One way to possibly parry such a request is to ask the contracting officer whether he believes adequate price competition exists and to provide a signed note stating that your company’s response was prepared independently and with the expectation of competition (assuming it was), affirming that the circumstances for adequate price competition are present. But the truth is that an aggressive contracting officer can intimidate most small and medium businesses into giving the government what the contracting officer wants.

Having a GSA schedule could put you in a stronger position when dealing with a contracting officer demanding data-other-than, because GSA must also determine prior to awarding a schedule contract that company prices are fair and reasonable. Granted, the methodology GSA uses to make a fair-and-reasonable determination depends on company disclosure of sales practices to the private sector, and so differs significantly from the processes we’ve detailed here. Plus, the terms and conditions for a GSA schedule compared to another procurement at another agency can differ and so affect the price. Nonetheless, if you can demonstrate that your current price proposal is derived from a price already formally declared to be fair and reasonable, that could be enough to satisfy the contracting officer.

By the way, you might think that a fair-and-reasonable price determination is meant to ward off excessively high prices, and you’d be correct. However, the government looks down equally at artificially low prices made in the expectation of sending through change orders to later increase company compensation. That practice is called “buying in,” and a contracting officer convinced that a company is lowballing the price will make a determination of contractor nonresponsibility, disallowing the company from winning the procurement.

Contract Types

Let’s now turn our attention to how the government deals with the financial risks in contracting, which it addresses through contract type.

Contract type defines the business relationship between a company and the government. It establishes methods of compensation according to how clearly the government understands its own requirements and how much risk it itself undertakes. The more precisely the government can define its needs, the more it will offload onto contractors the risk of executing them. The less sure it is, the more it has no choice but to assume that risk for itself.

Three main contract types exist: fixed-price; cost-reimbursable; and time-and-materials. The government can append incentives for good behavior to fixed-price and cost-reimbursable contracts, but not to time-and-materials contracts.

Fixed-price

Fixed-price is the preferred type within the federal government on the grounds that it forces vendors to be mindful of delivering on their promises because the contract value is mostly invariable. Fixed-price contracts are completion contracts, under which payment is contingent on delivery of a defined item or service. Because the price is fixed, the private sector takes full responsibility for all costs and the resulting profit or loss. (Price fluctuation clauses can be built into fixed-price contracts, but getting one for a standalone contract requires determined negotiation.) Generally, costs accrued by the vendor are (or are supposed to be) immaterial under fixed-price contracts.

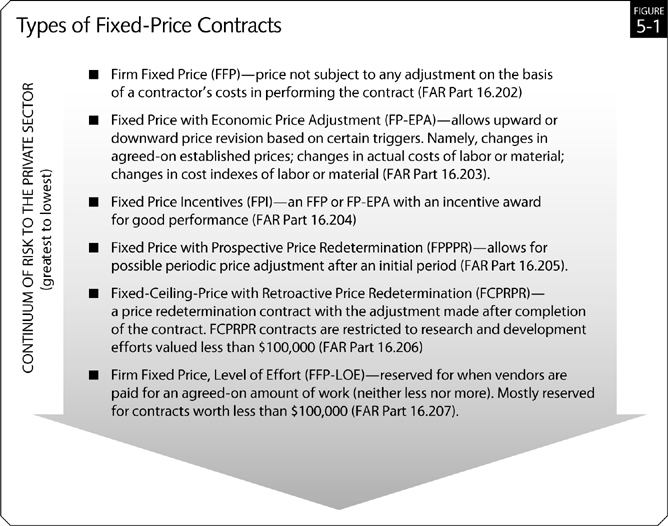

Figure 5-1 lists all fixed-price contract types. The government especially favors firm-fixed-price and fixed-price with economic price adjustment (FP-EPA) contracts when procuring commercial items.45 In theory, this works out great for everybody since commercial items should be the epitome of a well-defined item or service.

But, faced with pressure to avoid using other contract types, contracting officers sometimes attempt to administer firm-fixed-price contracts as if they were level-of-effort contracts, which are meant for situations where vendors are paid for the amount of work they perform, as opposed to delivery of a specific good or well-defined service. The DoD especially trains its acquisition workforce to favor fixed-price incentive and fixed-price redetermination over cost-reimbursement or time and materials, wherever possible.

What happens is that even though a firm-fixed-price contract price should not change on the basis of contractor costs, contracting officers at times ask for data other than certified cost-or-pricing data. For example, they’ll ask for a work breakdown structure based on hours by labor category, and then later, during contract performance, approve invoices based on hours, opening up the contract to allegations of time card fraud if the contractor has not documented time spent by each individual within each labor category precisely. As we discussed earlier, data-other-than can be anything a contracting officer finds necessary to determine price reasonableness.

Companies get little sympathy from the government should they stumble into this situation. The culture of some agencies encourages contracting officers to have it both ways when it comes to offloading risk to contractors. Their attitude is that if companies don’t like it, they can take their business elsewhere.

Cost-reimbursement

Cost-reimbursement contracts are level-of-effort contracts, mostly of the cost-plus variety—that is, the government pays vendors their costs plus a “fee,” which is how the government often refers to profit. Under level-of-effort contracts, the vendor is paid for work rendered irrespective of whether the intended goal gets accomplished. See the sidebar on this page for a list of all cost-reimbursement contract types.

The FAR bans cost-reimbursement contracts for acquisition of commercial items, so by definition these contracts are meant for occasions when an agency cannot define its requirements with precision, or for when those requirements are out of the ordinary.46

An inherent danger of even well-managed cost-reimbursement projects is scope creep, an easy trap to fall into when requirements are inexact. And companies have an incentive to rack up costs despite the safeguards against avarice baked into the terms and conditions of cost-reimbursement contracts.

Types of Cost-Reimbursement Contracts

- Cost: Contractor bills only costs and receives no fee. This type is mostly for use by nonprofit institutions conducting research and development (FAR 16.302).

- Cost sharing: Contractor receives no fee and even agrees to absorb a portion of the costs. Cost sharing is employed in cases where the work will result in benefits to the government and the vendor, so it’s only fair that both parties should share in the cost burden (FAR 16.303).

- Cost plus incentive fee (CPIF): Contractor receives a fee contingent on its performance, but that fee can go up or down—not just based on performance, but based on an inverse relation to how close the final cost is to the estimated total cost (FAR 16.304).

- Cost plus award fee (CPAF): Contractor receives a percentage of a standard incentive fee based on its performance (FAR 16.305).

- Cost plus fixed fee (CPFF): Contractor receives a fee set in advance that’s not connected to the final cost or to performance. Meant for use with research, preliminary exploration, or study of a system, or development and test, and not for development of a major system (FAR 16.306).

The first such safeguard is a cap on vendor profit of no more than 10 percent of the contract’s initial estimated cost—unless the work is for research and evaluation, in which case the margin is 15 percent, or for architect-engineer services, in which case it’s 6 percent.47 It’s illegal for the government to calculate a vendor’s fee as a percentage of actual costs instead of initial estimated costs. That’s known as a cost plus-a-percentage-of-cost contract, and civil servants tend to act like shocked gazelles when even just thinking about one.

Another safeguard is that the government carefully controls what’s an allowable cost, according to a set of cost principles found in FAR Part 31, as we mentioned briefly earlier.

At their most basic, federal cost principles divide costs into two categories—allowable and unallowable, with two further subcategories of allowable costs: direct and indirect (see Figure 5-2).

In the unallowable category are costs perfectly acceptable within the private sector, such as interest payments, uncollectible debts, entertainment, and most trade shows (unallowable costs are listed in FAR 31.205).

Companies must report allowable costs as either direct or indirect, indirect being things such as shares of overhead, employee fringe benefits, and general and administrative expenses.

As yet another level of precaution, the government generally reserves the right to audit your books.48

Finally, cost-reimbursement contracts come with a cost ceiling established by the contracting officer which only he may increase.

Yet safeguards can’t control for some facts of life. Contracting officers extend contracts or raise contract ceilings, and rare is the company witnessing scope creep that does anything except go along or even encourage it. The customer is king, after all.

Reimbursement for Government-Funded International Travel

Any contractor traveling outside the United States for government business with a ticket paid for by the government via a noncommercial-item contract (or grant) must do so on a U.S.-flag air carrier (FAR 47.402). This requirement comes from the Fly America Act, which, as amended, says the requirement is enforceable only when a U.S.-flag carrier is “reasonably available” (49 USC 40118(a)).

Cost accounting

Keeping track of costs requires a robust accounting system. Just how robust depends. Any private-sector entity holding a federal cost-reimbursement contract is subject to government cost principles. But they might also be subject to federal cost accounting standards (CAS), which prescribe in great detail accounting methodologies.

A fully spun-up cost accounting system requires records retention, documentation, and compliance with directions only expert accountants can stomach. Those standards are found in the FAR appendix, commonly referred to as FAR 99 because it reprints chapter 99 of Title 48 within the Code of Federal Regulations. Because federal cost accounting standards have no private-sector equivalent, most companies are rightly fearful of the expense and time it takes to set up a financial department capable of implementing them.

Accepting a cost-reimbursement contract does not automatically mean you must stand up a cost accounting system. Contracts worth up to the TINA threshold are wholly exempted from cost accounting standards.49 So can be contracts and subcontracts worth up to $7.5 million, provided that at the time of award, the business unit of the contractor or subcontractor is not currently performing any CAS-covered contracts or subcontracts valued at $7.5 million or greater.50 Small businesses are entirely excused—even if they have a cost-reimbursement contract.51 Even large companies selling exclusively commercial items can skirt by without having to install and maintain a FAR 99 cost accounting system. Contracts, no matter what their size, for commercial items made with firm-fixed-price, fixed-price with economic price adjustment (provided that price adjustment is not based on actual costs incurred), time-and-materials, or labor-hour (more about those shortly) contracts and subcontracts don’t require cost accounting.52

True, companies with a cost-reimbursement contract still need to account for costs according to federal cost principles (i.e., unallowable, allowable, direct, and indirect costs) even if they’re exempted from cost accounting standards. But there’s a significant difference in magnitude between an accounting system capable of dealing with the cost principles generally versus one that tackles the full rigors of the cost accounting standards set out in the FAR appendix.

If your company is a small business, know that even if you are a subcontractor to a large business that the government does require to have a cost accounting standards system, your business is not required in turn to set up such a system.53 Large businesses often try to flow all of their cost accounting standards requirements down to subcontractors. Small businesses should be leery of this for fear of having their margins unnecessarily diminished.

Time and materials

Time-and-materials contracts also are level-of-effort contracts that share much in principle with cost reimbursement—companies bill the government for labor hours (“time”) and cost of supplies (“materials”)—but differ in a few significant ways. First, the hourly rate under time-and-materials includes company profit, which brings us to the second major difference between these contract types: because the labor-hour rate includes profit, the federal government doesn’t separately incentivize good performance by tying profit to performance. This means that contractors have the clearest motivation to bill for as many hours as possible, leading policymakers to perceive time-and-materials as the riskiest contract type. To mitigate that risk, time-and-materials contracts come equipped with a ceiling amount that vendors exceed at their own risk, although a contracting officer can increase the ceiling. Finally, the FAR doesn’t exclude commercial items from procurement through time-and-materials contracts as it does with cost-reimbursement types.

The FAR inflicts very different amounts of pain on vendors and contracting officers when setting up time-and-materials contracts for commercial items (again, we use that term to include services) versus noncommercial items, specifically when establishing the fixed hourly rate prime contractors can charge the government when the prime uses subcontractors.

If the contract is for a commercial item, then there is minimal hassle in determining the hourly rate for labor categories. It’s whatever the contract award winner charges per hour.54 It’s between the prime and the subcontractor what the subcontractor gets paid. The regulations do allow primes to set up separate hourly rates for their subcontractors if they want, which they never do. However, if the commercial-item contract is made via a GSA schedule, the government can’t be billed more than the listed rate for the referenced schedule. If companies team up, the maximum rate for a task performed is the relevant team member’s listed schedule price.

If the item in question is not commercial, then the contracting officer must first determine whether adequate price competition among offerors exists. If it doesn’t, then the government won’t sign a time-and-materials contract without the prime contractor first revealing its labor rates, its subcontractors’ labor rates, and even the labor rate for work done by subsidiaries, affiliates, or other divisions of the prime contractor itself.55 By forcing the prime to divulge subcontractor or subsidiary labor rates, the government ensures the prime doesn’t reap excessive pass-through profit by simply hiring a cheaper company to perform the work.

If there is adequate price competition, then companies have the option of proposing separate rates for subcontractors, blended rates (a single rate per labor category that comprises prime and subcontractor rates), or a combination of separate and blended rates.56 In effect, this means that the highest rate among the prime and subcontractors will be the proposed hourly rate, because the FAR doesn’t specify how blended rates should be determined. An average of prime and subcontractor rates? The median rate? The FAR is silent, so the logical thing to do is propose the highest rate because actual rates charged only go downhill from there.

The Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) adds a twist for military contracting that’s worth noting. The DFARS requires all noncommercial-item proposals to include separate rates for the prime and its subs, whether adequate price competition exists or not.

Figure 5-3 shows all the possible outcomes of labor rate calculation.

As for overtime, unless the contract award directly allows for it, there’s no getting it. Even when contract terms and conditions do permit it, the contracting officer must approve the expense.57

When it comes to billing for materials, the rules are slightly more lenient. Invoices for materials include the direct and indirect costs not accounted for in labor rates.58 When the materials in time-and-materials contracts are items the prime itself manufactures, then the direct cost can be based on catalog or market prices. The word prices is significant because price includes profit, whereas cost does not. For an item to qualify for price reimbursement, it must be commercial, or priced according to the precepts of adequate price competition, or the subject of a waiver, or set by regulation. If the material is commercial, then the price can go down “to reflect the quantities being acquired,” or up if it needs to be modified, but only to reflect actual costs.59

Materials can even include “incidental services” outside approved labor categories for minor services, the need for which becomes apparent after the contract award.

A contract type this elaborate requires reams and reams of documentation. Companies submit time cards and evidence that employees meet the labor category qualifications before a contracting officer will process payment.60 Time and materials contracts are also a favorite target for federal auditors, so companies with these contracts should be ready to justify every expense to a team of skeptical examiners who show up one day to commandeer your conference room.

Complexity of this extent is not an accident. Policymakers are suspicious of time-and-materials contracts and want program offices to eat their vegetables, write specific requirements, and use firm-fixed-price contracts. Nonetheless, time-and-materials is a favorite type among federal agencies, since they’re flexible when it comes to adjusting labor-hour categories and adaptable to periods of uncertain funding. They’re particularly appreciated for gap-filler, ad hoc kinds of service requirements or when the number of tasks to be done is hard to estimate. Where time-and-materials starts becoming appreciably riskier for agencies is in long-term service engagements, when inertia can lead to racked-up billable hours.

Labor-hour

Labor-hour contracts are time-and-materials contracts without the materials.61 Companies with these contracts might find themselves working with GFP, which stands for government-furnished property and, colloquially, “government-furnished problems,” because GFP materials not infrequently show up late and in broken or defective condition.

Subcontracting Under Cost-Reimbursement, Time and Materials, Labor-Hour, and Letter Contracts (FAR Part 44)

How many hurdles a company with any one of the above contract types must jump before hiring a subcontractor depends in great part on whether it has an approved purchasing system (APS).

An APS is a purchasing system that ties government regulations to purchasing decisions, such that it allows contractors to certify cost or pricing data, implement cost accounting standards (if necessary), conform to government wishes in favoring certain socioeconomic classes of small business owners (see Chapter 11 for more on that), and give the government advance notice of a subcontracting decision when the subcontract is worth more than the simplified acquisition threshold, or 5 percent of the total estimated cost of the entire contract, whichever amount is greater. What constitutes “advance notice” of a subcontracting decision goes undefined in the regulations, meaning it’s something you’ll have to work out with the contracting officer.

The extra hurdle for companies without an APS is that advance notification gets replaced with government consent—that is, the prime contractor must await federal permission to hire a subcontractor. (Again, this applies only to subcontracts worth the greater of either the simplified acquisition threshold or 5 percent of the total contract.)

Sellers of commercial items are wholly excused from the consent or advance notification requirements, but this is actually small comfort, since by definition, cost-reimbursement, time-and-materials, labor-hour, and letter contracts are meant for situations in which commercial items can’t fulfill the need.

Letter

Sometimes work is too important to wait for the contracting shop to dot all the i’s, in which case the contractor and government sign a letter contract, which permits the company to start immediately manufacturing supplies or performing services.62 Within 180 days after signing a letter contract, or before 40 percent of the work is completed (whichever comes first), letter contracts should be converted into another contract type, or “definitized,” as the FAR puts it.63 Letter contracts restrict contractor payment to not more than half of the initial estimated cost of the work.

Waivers and approvals from higher-ups allow the government to bust definitization and payment restrictions. A 2010 audit conducted by the Defense Department inspector general of 41 Air Force letter contracts found that a third went undefinitized after 180 days.64 A separate 2010 inspector general audit of another Air Force command found that of 27 letter contracts, two-thirds went undefinitized for an average of 335 days.65

If for some reason the contractor and government can’t come to terms when definitizing a letter contract, then the government can force the contractor to complete the work under a price that it determines.

Contract Vehicles

Earlier, when discussing contracting methods, we mentioned that levels of competition vary for government opportunities. While we did bring up sole-source contracts (mostly to discuss their increasing disfavor in government), we generally deferred discussion about how competition is most often restricted. It is time now to directly address that.

A full and open competition for every single government procurement would be cost prohibitive and slow—not just for the private sector, but for federal agencies that manage competitions. Hence, the government created indefinite-delivery contracts. The basic idea behind them is for the government to award a single contract against which it can place multiple orders for goods and services for an extended period of time. Indefinite-delivery contracts typically last five years, including options.

The indefinite-delivery contract is technically a type of contract, but its purpose is different from that of the other types we just discussed. Those types—fixed-price, cost-reimbursement, time-and-materials, etc.—deal with how companies are compensated. As a type, an indefinite-delivery contract has nothing whatsoever to do with pricing. This fact is misunderstood by many, so it bears emphasis. Indefinite-delivery contracts do not establish how companies are to be compensated. In fact, indefinite-delivery contracts can use fixed-price, cost-reimbursement, or time-and-materials pricing types.

Also, indefinite-delivery contracts can be established with multiple contract methods, although a big chunk of them are done through full and open competition using the contracting by negotiation method. This is the main way in which the government attempts to reconcile the irreconcilable—by having a full and open competition among contractors that bid for the right to be given subsequent task or delivery orders under circumstances with far less competition.

The most famous type of contract vehicle, indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity, is known mostly by its acronym, IDIQ (pronounced eye-D eye-Q). Another two types, requirements contracts and definite-quantity contracts, are used much less frequently for information technology procurements, so we will very briefly mention them before we tackle IDIQs.

GSA schedules technically are indefinite-delivery vehicles, but since they’re unique in formation and in how the government uses them, we’ve chosen to deal with them separately in Chapter 10.

Requirements contracts

Under requirements contracts, the government picks one vendor to exclusively supply specific goods or services for which it has a recurring requirement.66 Requirements solicitations come with estimates of quantity, but the estimates aren’t binding. Requirements contracts aren’t used much in information technology despite their potential as a strategic sourcing instrument. They’re simply not worth the trouble. The government would have to analyze its spending patterns on a particular technology, define strict evaluation criteria, and then conduct a competition in which the winner would take all, making protests from losers a dead certainty. Other contract vehicles require far less planning and no up-front commitment from the government.

Definite-quantity contracts

Indefinite-delivery, definite-quantity contracts are used when the government has a recurring requirement of exact quantities from a single contractor whenever an order is placed.67 For regularly consumed, fungible commodities such as gasoline, definite-quantity contracts work just fine but, again, for information technology they’re not really relevant.

IDIQs

On to the exciting stuff. Under IDIQs, not only is the delivery of goods and services indefinite (i.e., not defined in the solicitation), but so is the quantity of goods and services federal agencies can order. Agencies can order goods and services up to a maximum value specified in the contract, which can be in the tens of billions of dollars. Setting up an IDIQ contract, especially one with many contractors, is a laborious affair for federal agencies, but they make little up-front financial commitment to companies at the moment of signing one.

An IDIQ with more than one contractor is called multiple award. Multiple-award IDIQs have become much more important in the past decade as a method of federal procurement, with big departments setting up vehicles with a Rolodex’s worth of companies on them.

It’s natural to think of every IDIQ as a multiple-award vehicle, since the whole point of any indefinite-delivery contract is for the government to place multiple orders over time. But once again, a federal predilection for particular terminology trumps intuitive logic. Gaining a slot on a multiple-award contract is a contract award. A transaction under which money changes hands and a company supplies goods or services—what most mortals think of as a contract award—is actually an order when done under an IDIQ. It’s called a task order for services and a delivery order for products. A multiple-award IDIQ is therefore an IDIQ contracting program with multiple contracts and contractors.

Multiple-award IDIQs constructed such that other government entities can make use of them are known as multi-agency contracts (MACs) or governmentwide acquisition contracts (GWACs). The difference between a MAC and a GWAC is how many agencies make use of the vehicle.

GWACs, as their name suggests, are meant for use by all government agencies. Federal entities hosting GWACs support their administration through fees paid to them on a per-order basis. Congress restricts GWAC contracts to information technology; there is no furniture GWAC. There are just three GWAC agencies as of this writing: GSA, NASA, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Each GWAC agency takes a different approach. NASA concentrates on high-technology products, NIH on IT goods and services for the federal health community, and GSA on casting the widest net possible.

MACs also permit multiple agencies to use its contracts, but regulations make it much harder for contracting officers to utilize another agency’s MAC. In the first place, in order for one agency to use another’s MAC, the two agency heads—who are expected to come from agencies with similar missions—must sign a memorandum of agreement. Departments also pressure their contracting officers into using their own agency’s MAC by making local IDIQs obligatory for consideration. Should a contracting officer press ahead anyway with an intent to use another agency’s MAC, he must sign a determination and finding that the order is the “best procurement approach” (except when placing GSA schedules worth $500,000 or less).68 Remember, how the government chooses what to buy is often not a function of what’s best, but of how easily it can buy it.

Companies hotly compete to be on multiple-award IDIQs because so many contracting dollars are funneled through them. Yet winning a slot on a contract vehicle (whether a plain IDIQ, a MAC, or a GWAC) is no guarantee of getting any federal business. An agency administering a multiple-award IDIQ must permit all of its contractors a fair shot at all ordering opportunities, so it holds a second round of competition among the IDIQ awardees any time a buyer wants to place an order. From a vendor’s perspective, a multiple-award IDIQ contract is nothing but the ability to compete yet again, albeit on a much smaller playing field.

That second round is called the fair opportunity process, and it involves providing notice of every order opportunity that’s worth more than the simplified acquisition threshold, including a description of what’s to be procured, and allowing IDIQ holders a chance to respond to the opportunity.69 Contracting officers must go through the fair opportunity process even if, as a condition of granting a company a slot on an IDIQ, they declare that the contract prices are fair and reasonable. They can, however, exempt particular orders from the fair opportunity process on similar grounds to those used to justify sole-source contracts.

Agreements

Indefinite-delivery contracts are not the only type of vehicle to facilitate future ordering. There are also agreements. Technically, agreements are not contracts and it’s tough to say anything meaningful about them as a class, so varied are the individual types.

Traditional blanket purchase agreements

A traditional blanket purchase agreement (BPA) is a type of simplified acquisition analogous to a charge account with a regular supplier.70 A traditional BPA is really just an agreement that the government can buy now and pay later, probably on a monthly basis. Only a warranted contracting officer can establish a BPA, but any government employee so authorized by the BPA can place an order.

Schedule blanket purchase agreements

BPAs established pursuant to a GSA schedule play by different rules than traditional BPAs. Schedule BPAs themselves aren’t contracts in the sense that they obligate the government to purchase anything from the BPA holder. However, because a schedule BPA explicitly references one or more GSA schedule contracts, orders from schedule BPAs must comply with the regulations governing buying from schedules.71 The terms and conditions of the company’s schedule contract also apply.

Government use of schedule-based BPAs has skyrocketed in recent years—a recent GAO report found that civilian agency usage of them from government fiscal year 2004 through 2008 rose 382 percent, from $659 million annually to $3.2 billion in constant 2008 dollars.72

Basic agreement

Basic agreements (BAs) are barely agreements at all—more like a collection of negotiated contract clauses a contracting officer can incorporate by reference into individual contracts made with the same company.73 A BA isn’t a contract—it’s barely even a framework, since terms and conditions can still vary for individual contracts executed under a BA. Essentially, BAs are made when the government awards many standalone contracts to a particular company and wants to standardize as many of those contracts as possible.

Basic ordering agreement

A basic ordering agreement (BOA) is different from a BA mainly in that a BOA defines terms and conditions for contracts (orders) issued under it.74 A BOA also is not a contract.

Contract Changes and Equitable Adjustment

The government reserves for itself the ability to unilaterally modify contracts via a change order, though the modification can’t change the scope of the contract.75 A company hired for consulting can’t be forced into janitorial services, no matter how positive a net effect on productivity that would have. (An out-of-scope contract change is grounds for a breach of contract lawsuit.)

Although mainly a separate issue from changes, we should quickly mention that the government also can outright cancel a contract even if the contractor hasn’t done anything wrong, thanks to a universally applied termination for convenience clause; we discuss terminations in the next chapter.

Changes can range from a minor administrative update to enforcement of an entirely new technical standard being adopted by the government. They might also result from clarification of ambiguous specifications, a government delay of work, a change in expected funding, or other circumstances. Government policy is to price a modification before enacting it, as much as is possible.76

When implementing a change order, a contracting officer must make an equitable adjustment, should the change cause a material difference in contractor costs or time of performance.77 This means that any time the government makes a modification that adds or subtracts work, including a substitution that involves elements of both, companies have 30 days from receipt of a written change order to submit a claim for adjustment.78 If the change has the effect of reducing costs, the government will seek a refund or reduction in price. It’s important to note that if a modification has the effect of reducing a subcontractor’s costs, the prime could be the one forced to pay the reduction amount, unless it has written into its own subcontractor contract a flow-down cost adjustment clause.

If you believe the government has effectively introduced a contract change but hasn’t formally modified the contract—what’s called a constructive change—you can ask for a contract modification. You might do so if, for example, it becomes apparent that there’s an unwritten requirement not accounted for in the contract line items, or if the government interpretation of the CLINs causes extra work. Your first step would be to notify the contracting officer and provide as much documentation—names, dates, descriptions, documents, etc.—as possible.79

Sometimes a constructive change becomes apparent only in retrospect, in which case you should probably just file a request for equitable adjustment (REA). Whether the government will give one or not depends greatly on how much evidence you can provide showing that the change was the result of government action. An attempt to get an equitable adjustment based on the mere fact that actual costs were higher than anticipated won’t go anywhere; you can’t use an equitable adjustment to get well.

Two basic principles gird equitable adjustment. First is that adjustment is based on vendor costs, not price. The second is that an equitable adjustment can’t be used to decrease or increase a contractor’s profit.

The government strongly prefers to take what’s called a reasonable cost approach when approving an equitable adjustment. A reasonable approach takes into account the cost of the added work, the estimated direct cost of deleted work not yet performed, indirect costs affected by the modification (obviously, some indirect costs are fixed), and profit.

The “reasonableness” in a reasonable cost approach comes from an assessment of whether the cost was necessary, consistent with sound business practices, and prudent.80 If a contracting officer believes a cost is excessive, he will challenge it. Once challenged, there is no presumption of reasonableness in the cost figures submitted by a contractor.81 The burden of proof rests on the contractor to substantiate a challenged cost. In other words, be prepared to back up your figures to the hilt. Also be prepared to answer why, if a cheaper alternative existed, your company didn’t choose that alternative.

Companies must make a “good faith” certification that the data underlying claims for adjustment worth more than $100,000 are accurate and complete.82 A claim worth more than the TINA threshold (currently $700,000) made in relation to a negotiated procurement must be calculated using certified cost-or-pricing data. So too must modifications to commercial-item contracts with the DoD, NASA, and the Coast Guard if the modification is worth the greater of the TINA threshold or 5 percent of the contract value.

When it’s impossible for a contractor to segregate cost changes caused by a modification, two methods are available for determining the amount of a claim: the jury verdict approach and the total cost approach.

In a jury verdict approach, the government and contractor present cost estimates based on the opinion of qualified experts and can challenge the opposing side’s figures; as its name suggests, it’s often used when there’s a disagreement between contractor and government.

Total cost is the least favored approach and the most difficult for a contractor to prove. Under it, the settlement equals the costs assumed in the proposal minus the actual costs of performance plus profit. Total cost is permissible only when no other method is available, and even then a company must jump through some eligibility hoops to get a settlement.

If a company and the government can’t come to agreement over an equitable adjustment, the contracting officer will issue a unilateral final decision. A company sufficiently unhappy with the dollar amount can file an appeal, either with a board of contract appeals or the Court of Federal Claims (COFC), but not with both simultaneously.83

Two boards exist—the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals and the Civilian Board of Contract Appeals, each with jurisdiction over the parts of the federal government that their names suggest. Under the Contract Disputes Act of 1978, the boards can decide all contract disputes arising under the administration of a government contract.84 The COFC is the judicial venue for hearing claims against the federal government. (It also hears contract protests, which we discuss in Chapter 8.) Boards issue administrative decisions, while the COFC gives out civil decisions.

Which venue is best is probably a matter for a lawyer to decide, and depends on factors such as attorney preference and precedent. Since none of these venues are bound by precedents established outside their bailiwick (and judges in the COFC aren’t even bound by each other’s decisions), each venue might be uniquely disposed toward a particular interpretation of acquisition regulations. There’s also the matter of timing. An appeal to a board over a contracting officer’s decision must be filed within 90 days, whereas you have 12 months to file with the COFC.85

Another factor to consider is that the boards are less formal than the court; the COFC is bound by the federal rules of civil procedure. Less formal, in the world of attorneys, translates into less expensive. Also, if you lose at the board, the COFC remains open as a de facto appeals venue. If you start at the COFC, the next step is the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and after that, the Supreme Court.

Final Note

Federal contracting, as you’ve no doubt come to appreciate, can get complicated. Even contracting officers often are not fully aware of all of its complexities, much less a vendor whose focus is rightly on goods and services and delivering customer satisfaction. So it’s easy to slip into a variety of pitfalls. Over the years, we’ve noted a number of them and here present a list of some of the most important ones to avoid:

• Working without a contract signed by a contracting officer

• Providing services outside the scope of the contract

• Failing to read the contract as a whole and to perform accordingly

• Failing to get a signed contract modification if something changes

• Trying to get a modification that exceeds the scope of the existing contract

• Not knowing the purpose of a requested quote

• Forgetting that a quote is not an offer

• Quoting without referencing license or terms of service

• Accepting an order when terms aren’t correct

• Calling your item(s) commercial to avoid disclosing cost and pricing data when your only customer is the federal government

• Failing to fully substantiate expenses

• Arguing with a contracting officer.

ENDNOTES

1. Sealed bidding is described in FAR Part 14.

2. We refer to the Competition in Contract Act, implemented in FAR Part 6.

3. Reverse auctions are not, in fact, expressly permitted by the Federal Acquisition Regulation. It may be surprising, then, that contracting officers use it, since they generally prefer methodologies to be well-defined in the regulations. But FAR 1.102(d) allows the government to use any procurement procedure that’s not specifically prohibited, and agencies have used that authority to permit reverse auctions.

4. U.S. Government Accountability Office. MTB Group, Inc. B-295463. February 23, 2005.

5. Contracting by negotiation is described in FAR Part 15.

6. FAR 15.404.

7. FAR 15.208(b).

8. Ibid.

9. FAR 15.306(c).

10. FAR 15.505(a).

11. FAR 37.102.

12. U.S. Government Accountability Office. Department of Homeland Security: Better Planning and Assessment Needed to Improve Outcomes for Complex Service Acquisitions. GAO-08-263. April 22, 2008.

13. Simplified acquisition procedures are described in FAR Part 13.

14. FAR 13.106-2(b).

15. As with the micro-purchase threshold, if the products or services in question are for a contingency operation or for defense against or recovery from a nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological attack, the threshold shoots way up. In this case, it increases to $300,000 inside the United States and $1 million outside it.

16. Once again, purchases for contingency operations or defense against or recovery from a nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological attack have a much higher limit: $12 million.

17. FAR 13.500.

18. FAR 13.003.

19. FAR 13.004.

20. U.S. General Accounting Office. Computer Associates International, Inc.—Reconsideration. B-292077.6. May 5, 2004.

21. FAR 6.302-1 to 6.302-7.

22. FAR 15.101.

23. FAR 15.304.

24. FAR 13.106-2(b).

25. FAR 13.106-1(a)(2).

26. FAR 6.303-2(a); 12.209; 13.106-3; 14.408-2; 15.402(a).

27. FAR 13.106(3)(v).

28. FAR 15.403-1(c)(1).

29. Until fall 2010, this was also the case for the Defense Department. But DoD then issued guidance telling contracting officers that in the event of a single response to a solicitation, they had to open price negotiations on the basis of internal company cost-or-pricing data, whether certified or not. As of this writing, the DoD guidance hasn’t been codified into the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), and there’s some talk about making the negotiations mandatory only for procurements above the simplified acquisition threshold. The rule probably won’t achieve its final shape for a couple more years. The DFARS case number is 2011-D013.

30. FAR 15.404-1(b)(1).

31. FAR 15.403-4.

32. Under unusual circumstances, the government can extract cost-or-pricing data even if the contract is worth less than the TINA threshold—but never if the value is under the simplified acquisition threshold (FAR 15-403-4(a)(2)). On the other hand, acquisitions of goods or services used for the defense against or recovery from a nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological attack are always exempt from cost-or-pricing data requests, unless the acquisition is made with a sole-source contract and is worth more than $17.5 million (FAR 15.403-1(c)(3)).

33. FAR 2.101.

34. FAR 15.406-2.

35. FAR 15.407-1.

36. FAR 52.215-2(f).

37. FAR 15.406-2(b).

38. FAR 15.403-1(c)(3).

39. FAR 15.403-4(a)(1)(iii).

40. Ibid.

41. FAR 15.403-1(c)(3).

42. FAR 2.101.

43. FAR 15.403-3(a)(4).

44. FAR 15.402(a)(1).

45. FAR 12.207.

46. FAR 16.301-3(b).

47. FAR 15.404-4(c).

48. FAR 15.209(b) and 52.215-2(b).

49. FAR 9901.306.

50. FAR 9903.201-1(b)(7).

51. FAR 9900.000.

52. FAR 9903.201-1(b)(6).

53. FAR 9903.201-1(b)(3).

54. FAR 52.216-31.

55. FAR 52.216-30.

56. FAR 52.216-29.

57. FAR 52.232-7.

58. FAR 16.601(b).

59. FAR 31.205-26.

60. FAR 52.232-7.

61. FAR 16.602.

62. FAR 16.603.

63. FAR 16.603-2.

64. U.S. Department of Defense. Office of Inspector General. Air Force Electronic Systems Center’s Use of Undefinitized Contractual Actions. No. D-2010-080. August 18, 2010.

65. U.S. Department of Defense. Office of Inspector General. Air Force Electronic Systems Center’s Use of Undefinitized Contractual Actions. No. D-2011-024. December 16, 2010.

66. FAR 16.503.

67. FAR 16.502.

68. FAR 17.502-1 and 17.500.

69. FAR 16.505(b)(1).

70. FAR 13.303.

71. FAR 8.405.

72. U.S. Government Accountability Office. Contract Management: Agencies Are Not Maximizing Opportunities for Competition or Savings Under Blanket Purchase Agreements Despite Significant Increase in Usage. GAO-09-792. September 9, 2009.

73. FAR 16.702.

74. FAR 16.703.

75. FAR 43.201(a).

76. FAR 43.102(b).

77. FAR 43.205 and contracting clauses 52.243-1(b) for fixed-price contracts; 52.243-2(b) for cost-reimbursement contracts; and 52.243-3(b) for time-and-materials or labor-hour contracts.

78. FAR 52.243-1(b) for fixed-price contracts; 52.243-2(b) for cost-reimbursement contracts; and 52.243-3(b) for time-and-materials or labor-hour contracts.

79. A contract clause describing the exact procedure is found in FAR 52.243-7. Contracting officers are meant to insert that clause only into contracts worth at least $1 million let for research and development or supply contracts for the acquisition of major weapon systems or principal subsystems, but the procedure could be used under any circumstance as a template.

80. FAR 31.201-3.

81. FAR 31.201-3(a).

82. The exact certification the contractor must make is “I certify that the claim is made in good faith; that the supporting data are accurate and complete to the best of my knowledge and belief; that the amount requested accurately reflects the contract adjustment for which the contractor believes the Government is liable; and that I am duly authorized to certify the claim on behalf of the contractor” (FAR 33.207(c)).

83. FAR 33.211(a)(4).

84. 41 USC 601–613.

85. FAR 33.211(a)(4).