Chapter Five

![]()

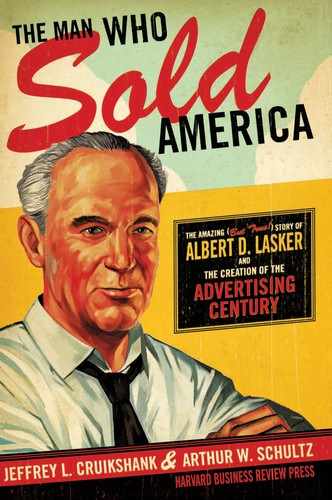

Growing Up, Breaking Down

![]()

ALBERT LASKER arrived in Grand Rapids, Michigan, late on a blustery November night in 1900. Although only twenty years old, he was already a highly successful advertising salesman—making $3,600 per year, and on a productive day placing $800 worth of ads.1

He had spent the day with a manufacturer out in the country, and didn’t get back to his hotel until after 10 p.m. In those days, most travel was done by train and horse-drawn wagons. As soon as the streets in the northern reaches of the Midwest acquired their five-month mantle of snow, the wheels were removed from horse-drawn vehicles and replaced with runners. Travel that was already slow got slower, and the life of a salesman got harder.

Gratefully ducking into the lobby of his Grand Rapids hotel to escape the blizzard outside, Lasker wore his Elks pin prominently displayed on his lapel. He had no interest in the Elks, but he had discovered that a surprising number of hotel clerks were Elks. Wearing his pin often got him better accommodations than he could secure otherwise.

Tonight the lobby was crowded, with scores of men seated in lounge chairs, smoking and talking, making the steamy air even more stale than usual. A short, chubby young man spotted Lasker’s pin and enthusiastically gave him the Elks handshake. The young man introduced himself as Arthur Warner. He was a salesman from Buffalo, and wanted to have a drink with his fellow Elk. Lasker could tell that Warner—like himself, little more than a teenager—had already had a drink or two. He declined, saying that he was tired and wanted to go to bed, but Warner persisted.

“I thought that I would teach him a lesson,” Lasker later recalled. “Not that it was my business to teach him a lesson.”

Off the lobby was a poolroom with a huge bar, which on this wintry night was doing a booming business. Lasker walked Warner up to the bar, and said he would drink with him if Warner would match him drink for drink. Warner agreed. Lasker then called for two beer glasses and a bottle of whiskey. Filling his own glass with whiskey—eight ounces’ worth—he challenged Warner to fill the other glass and drink it “bottoms up.”

“I figured he wouldn’t do it,” Lasker admitted, “and I would be rid of him.”

The challenge attracted the attention of many of the bar’s patrons. The pool players put down their cues, crowding around the two Elks at the bar. Warner lifted his beer glass and chugged its entire contents. Lasker, now remembering that he hadn’t eaten anything in many hours, did the same.

The huge slugs of alcohol soon swamped their brains, and what followed was a long night of half-remembered antics. “We Elked all night long,” Lasker recalled ruefully.

They staggered outside and ran into an elderly cabman, and soon both Lasker and Warner were reduced to weeping at the realization that this poor old fellow had to wait outside in the subzero temperatures while they sat inside drinking. Lasker pressed a few dollars on the cab driver—a large sum, in those days—then took the reins of the carriage, the better to show Grand Rapids to his fellow Elk.

At one point deciding that they needed another drink, Lasker spied a bar that looked promising. Like many saloons of that era, this one had two sets of doors—one a pair of swinging shutters, and behind them, a pair of glass doors. Sending Warner ahead on foot to open the inner doors, Lasker then attempted to drive the carriage into the bar: “I do distinctly remember getting the horse through the swinging doors, by golly, and the fellow who was running the place threw a knife at us, and we went away.”

The two Elks stumbled back into their hotel as the sun was coming up. Lasker was fine, but Warner felt deathly ill. Lasker concluded that his suffering companion needed food, and ordered two enormous breakfasts: fruit, bacon and eggs, toast, and coffee. When the food arrived, Warner became violently ill—“the sickest boy I ever saw in my whole life,” Lasker later remembered. “I never saw a man that ill.”

Lasker ate both breakfasts and went off to his nine o’clock appointment. For the rest of the day, whenever he had a free moment, he checked in on the ailing Warner. This solicitude—as well as his cast-iron stomach—earned Lasker the lifelong admiration of Arthur Warner: “He kept writing me letters, and he would write me at great length. Sometimes I wouldn’t answer the letters, or sometimes I would just drop him a few lines. But the fact that I could eat that breakfast always made him think that I was the greatest living male in America.”

Everything about the experience seemed to relegate it to the closet of embarrassing tales from the road. To Lasker’s surprise, that proved not to be the case.

About a month later, on the Saturday night between Christmas and New Year’s Eve of 1900, Lasker was seated in the Munro Baths in Cincinnati, a city he often visited to service the Rheinstrom account. In a Turkish bath, travelers rented rooms without separate bathing facilities, and met downstairs in the common baths for the steam and the male camaraderie. Lasker had gotten to know a number of the young single men who frequented the Munro Baths fairly well. Many were Jewish, like himself. They called each other by nicknames, and engaged in easy banter.

In the previous few weeks, Lasker had been doing some serious soul-searching. He had been at Lord & Thomas for two years. He no longer dreamed of leaving for New York to become a reporter; now he aimed to “conquer advertising,” make a lot of money, and then go buy a newspaper.

But there were at least two obstacles. The first was that by his own estimation—perhaps tinged with some fresh guilt—he was reckless and irresponsible. The antics in Grand Rapids weren’t an isolated incident but part of a recurring pattern. “I wasn’t getting rid of them,” Lasker admitted.

The second problem was that he was terribly lonely in Chicago. During the Thanksgiving holiday a little more than a year earlier, he had acted on his loneliness in an almost desperate way:

I remember going to my room and crying in a paroxysm of tears. Within an hour, I went down to the station and took the train for Galveston, which at that time was a 48-hour trip from Chicago. I wrote a note to Mr. Thomas, and just told him that my homesickness had grown so nostalgic that I couldn’t resist it. Maybe he’d understand it, and maybe he wouldn’t. Would he send me a wire whether or not I could come back to work?

Thomas reassured his troubled young colleague that he was welcome to come back to work. But the isolation that Lasker felt in Chicago soon closed in around him again and reinforced his tendency toward obsessive thinking: “I was very introspective on certain things. And I made up my mind that what was the matter with me was that I was just sheer lonesome, and if I had a home, I could get ahead, and I would settle down.”

On this particular night, downstairs in the Turkish baths, Lasker and his cronies were playing poker and drinking. The members of the group were between half a decade and a decade older than Lasker, and regarded him as a precocious teenager. It was now 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning: an hour when troubled young men are sometimes given to startling confessions. On this night, Lasker didn’t disappoint: “I said, ‘This is all foolishness—my staying up like this. I am only going to be young once, and every day counts. I want to make my youth accumulate experience, and this thing that I am doing isn’t good for me, and anyway, I have done it enough . . . If I could meet the right type of girl, I’d get married.’”

His companions egged him on. What kind of girl, Lasker? What would she look like? Lasker obliged with a detailed description of his ideal woman. Well, we know just the type of girl you described, they responded. She’s visiting here at Elsie Bernard’s, and we can take you over there this afternoon. But this unexpected opportunity confronted Lasker with another problem. Although he was nearly twenty-one years old, he was insecure with women: “I wasn’t much for going socially with girls, and I was always self-conscious that I wouldn’t know how to conduct myself. It was all right with the males, but I didn’t know how to sell a female, and I guess my lack of confidence telegraphed itself to them.”

Lasker may have known more about women than these comments suggest. Photographs of him in his late teens and early twenties show an intense, handsome young man with wavy black hair and deep-set, expressive eyes—certainly attractive enough, especially considering his sparkling wit and ready cash. During his theater-reviewing days in Galveston, for example, Lasker happily caroused with the choruses of touring theater companies, including the actresses. “I’d party with them,” Lasker recalled, “which no boy in Galveston had ever done.”2 But this kind of experience hardly prepared him to court a socially appropriate woman.

To make matters worse, Elsie Bernard—a prominent young socialite in Cincinnati’s affluent German-Jewish community—had met the awkward Lasker on one of his previous trips to town and made it clear that she didn’t much like him. Lasker decided that, if only to aggravate Bernard, he would go meet the out-of-town visitor staying at her house.

Later that afternoon, Lasker’s cohort of gregarious young companions arrived at the Bernard house. Lasker, still feeling the effects of the previous night’s carousing, now had second thoughts about this adventure. Those misgivings vanished, however, the moment he was introduced to Elsie Bernard’s guest. He promptly forgot her name, but he didn’t forget much else about her:

She weighed about 108 pounds, just as thin and straight, with that boyish figure that later came into popularity, but at that time you were supposed to be considerably plumper. She had the biggest eyes I had ever seen, before or since, coal black, and coal-black hair, and I remember she had on a blue dress with white dots, and coral beads, and her hair hung in a loop on the back of her head.

She had an infinite amount of charm, of gentility, of kindness, of breeding. You could tell that she was beautifully reared, and well educated, sensitive, and artistic. And, my! I hadn’t seen her one minute that I fell like a thousand.

The young woman soon was whisked off, and Lasker now felt excruciatingly out of place. In his oddly sheltered life, he had never before been in a social setting anything like this. He couldn’t bring himself to say a word to anyone: “Just everything I had in me closed up.”

He sat down on a piano bench, and to his surprise, the beautiful young woman with the enormous eyes sat down next to him. She again told him her name—Flora Warner—and said that she was nineteen years old; this was her first trip away from Buffalo. Remembering his escapade in Grand Rapids, and startled by the unlikely juxtaposition of “Warner” and “Buffalo,” Lasker found his tongue. He asked if she was related to Arthur Warner.

Why, yes, she replied, surprised. Arthur was her first cousin, and lived next door to her in Buffalo. They had grown up together since birth, and were virtually brother and sister. When she finally excused herself to rejoin her friends, Lasker sat there dumbfounded:

The minute she was called away, that whole place was empty for me. I was just a lovesick calf . . .

All I knew, from that second, I knew I loved that girl. I had never had a girl, but I knew I loved that girl, and I knew that girl could supply what I lacked.

He sought out his friends and told them that he was ready to leave. When they asked what he had thought of the visiting socialite from Buffalo, he told them, “I am going to marry that girl.”

![]()

Aside from the fact that Flora had no notion of marrying him, there were some major impediments to this New Year’s resolution. First, he needed to get his father’s consent to court a young woman. (He could no more get married without his father’s permission, he explained, than he could go out and commit a robbery.) That night, in his cramped quarters at the Munro Baths, he wrote Morris a long letter, explaining his intentions and asking for Morris’s blessing.

The letter he received in response—on January 4, 1901—brought an unwelcome message. There was nothing Morris wanted more than to see his son happily married. At the same time, certain facts weighed heavily on his mind. He knew his son had been drinking a great deal and, in his opinion, Albert had no right to ask a decent girl to marry him. Therefore, he would withhold his blessing until his son had abstained from alcohol for six months.

Albert wrote back immediately, agreeing to the terms. He then began taking steps to increase his chances of success in the larger campaign. First, he resumed his correspondence with Arthur Warner. Concurrently, he also approached Ambrose Thomas with a proposition. The Pan-American Exposition—the World’s Fair—was then under way in Buffalo. It was a celebration of industry and commerce, with awards of all sorts being passed out to exhibitors. At the Frankfurt World’s Fair in 1891, Lord & Thomas had come up with a plan whereby, for a modest fee, the agency would help award-winning U.S. manufacturers trumpet their successes by sending press releases to selected newspapers. Lasker proposed to revive this program for the Buffalo exposition—only this time, for a much bigger profit. Instead of the $1,200 or $1,500 that Lord & Thomas had charged for the service previously—a fee that already had included a “big profit”—now the firm would charge between $3,000 and $4,000. Thomas readily agreed. And even though Buffalo was not in his territory, Lasker got himself assigned the Exposition job, which would give him ample reason to visit Buffalo at the firm’s expense.

Lasker kept his promise to his father, refraining from taking a drink for the entire first half of 1901. It was probably a difficult challenge. Lasker once admitted that he “drank heavily for years.” He owned up to getting drunk with the hard-bitten newspaper reporters back in Galveston; he also commented that during his early days in Chicago, “all advertising men drank a great deal.” He was constantly surrounded by alcohol and alcoholics, and life on the road was often lonely.

In June, Lasker wrote Arthur Warner to say that he was coming to Buffalo on Wednesday evening, July 3. He would be staying until Sunday night, and hoped to spend the evenings and the holiday with him. Arthur wired back that he would be delighted to host his friend.

Lasker took a train up to Buffalo from Cleveland, arriving at around 9:00 p.m. Warner met him at the train station, and exclaimed excitedly that they were going to have a “great time tonight.”

Now, though, Lasker confessed to Warner that he had come to win the hand of Warner’s cousin, Flora. Warner, laughing, said that Flora had been engaged for several years, and it was only a matter of time before she married her Buffalo beau. Lasker asked if this was a formal engagement; Warner admitted that it was not. In that case, Lasker replied, there was no problem:

I said, “Oh, that makes no difference to me, if she isn’t [engaged], I’ll tend to that . . . But you have met other fellows. If you think I am earnest, and think I am going to get along in the world—if you think you are doing your cousin a favor—I want you to direct me to her.”

He said, “Why, I know you are going to be a success, and I know I am doing my cousin a good turn. I love her as much as anybody can love anybody. I’ll do anything you ask me to do.”

So we went out that night and had quite a time. And that night, that part of my life was buried, and never rose again.

The following morning—Thursday, the Fourth of July holiday, 1901—Lasker arrived at Arthur’s house on Main Street. There he found a unique living arrangement: Arthur’s and Flora’s fathers were in business together, lived in identical and adjacent frame houses about fifteen feet apart, and drew from a communal financial pot. In a chair on the front porch of Flora’s house was a woman—a “lovely motherly looking old lady,” to Lasker’s eyes—Flora’s mother.

Arthur and Lasker casually wandered over and inquired where Flora might be. The woman replied that she was out playing tennis and wasn’t expected back before lunch. Arthur leaned over and whispered something in her ear, and she got up and went inside. Shortly thereafter, a young boy emerged and sped off on his bicycle. And not too long after that, Flora arrived on her bicycle, wearing a long white tennis dress. She shook Lasker’s hand politely, excused herself, and went inside.

Once in the house (Lasker later learned) a furious Flora confronted her mother. Who did this Lasker think he was, interrupting her tennis game? Flora’s mother scolded her, and sent her back outside to be hospitable to the nice young man who had come visiting all the way from Chicago.

Over the next seven weeks or so, Lasker arranged to be in Buffalo four times on business, each trip lasting three or four days. He pressured Flora to break whatever engagements she had and to spend time with him:

With Art’s connivance, we arranged it all around, he telling her, and I rehearsing with him what I wanted represented as my fine points. We put a little glamour to me, and a little mystery to me, and made me on the one hand very attractive, and—on the other hand—just put in enough about my being a boy of the world to a girl of that type [to] be intriguing.

I would send her little things from the towns I went [to], that she couldn’t get otherwise, and I made no concealment that I was enamored beyond measure. And at the same time, made no forward move, wasn’t bold, held back, and was plainly bashful and worshiping in her presence, but plainly that behind that, that I could get aggressive if I wanted to.

That is the only piece of salesmanship I ever did study, and I went at it as an actor would, to create a part. I saw she was very romantic, and I didn’t have any romance in me. But I put on an act that would appeal to a romantic girl.

Calculating he may have been, but the more he learned about Flora, the more he loved her. Although she was Jewish, she had been educated in a Buffalo convent. Influenced by these two faiths, Flora had a strong moral streak. And although she had told him she was nineteen when they first met, she was in fact twenty-one, a year older than Lasker—a fact that caused her great embarrassment.3 She made him promise never to reveal this to anyone, even to the three children they eventually raised together.4

A letter to his father from August 1901 suggests that Albert did not control the courtship quite as deliberately as his comments above would imply: “I am in that state of constant mental worry—a hell on earth—where I must take some immediate action. I won’t enter into any extravagant phrases as to how deeply I love—all I know is, I must end this mental torture or I don’t know what will happen.”5

Lasker again asked for his father’s blessing. In remarkably plain logic and language—good reason-why advertising copy, in fact—he laid out his case before his father:

In considering this matter please remember:

First: I was never overly wild.

Second: The girl shall know the whole situation.

Third: My earning capacity is sufficient.

Fourth: I know I am settled.

Fifth: I propose a year’s engagement.

Sixth: How I love this girl.

Seventh: That I’m not worth a dam [sic] to anyone until I get this settled.

Morris telegraphed his response to the Hotel Iroquois in Buffalo, where Albert was staying: Go ahead. I am with you. She must be a good girl or you could not love her so much. He also loaned his son $125 for an engagement ring. Albert promised to pay back the $125 before the wedding, should it take place.

On the evening of August 30, Lasker took Flora to have their fortunes told by Julius and Agnes Zancig, a celebrated pair of fortunetellers on the midway at the fairgrounds. According to Lasker, both he and his beloved were under “equal strain” because of the large, unspoken topic on their both of their minds:

There was a beautiful full moon, and the setting was quite exotic at the fair . . . And she looked up and said, “Couldn’t you just love a moon like that?”

And I said, “Why, if you have love to spare, do you give it to an inanimate thing like the moon? Why don’t you give it to me?”

And she turned to me and in all seriousness said, “Are you by any chance proposing?”

“Indeed I am—I’m asking you to be my wife,” I said. “What is the answer?”

And she said, “Why, I have never given it any thought. I’ll have to think it over.”

And I said, “I can’t give you an option. I’m a young man trying to get along in the world. I have a career in front of me that I want to share with you, and if you get someone to tell you about it, you will see that I am hard-working, and have already taken too much time coming here . . . You will have to tell me yes or no, because I have to get along with my career.”

At that moment, they arrived at the fortune-tellers’ door. They entered and sat down together for their reading. Agnes Zancig told Flora that she would have a long and serious illness from which she might never fully recover. And, she continued, Flora would be going on a long and joyous journey. Flora turned, looked at Lasker, and asked, “Are we?”

And that was how Albert Lasker and Flora Warner became engaged. Lasker was thrilled:

I had never called her anything but “Miss Warner,” up to that moment. And more than anything else in the world, I wanted to kiss her, to seal the bargain . . . We were both trembling, and mind you, she was a girl [in] the spirit of [the] mid-Victorian[s]. Never did anything without her parents making the decision, and here she had gotten herself engaged.

And here I proposed that we go on the roller coaster, on which you come to a dark spot. And when we came there, I put my arm around her, because I had never thought of it, I put my lips to hers, and said, “May I, Miss Warner?”

I want to say, there is all the romance there has ever been in life, before or since—that is all the romance.

Fortunately, the Warners didn’t stand in the way of the match.6 Flora’s father, half Hungarian and half Austrian, actually knew Lasker’s celebrated Uncle Eduard, and that was enough of a reference for him. Morris Lasker traveled to Buffalo to meet his prospective daughter-in-law, and again gave his blessing.

The wedding took place in Buffalo on June 9, 1902. The delay resulted from the fact that Albert had promised his father a long engagement, and also from the fact that Morris’s family was still in Europe, where he had sent them in his efforts to economize, and they couldn’t get back any sooner. Flora wanted a large wedding, to which Lasker very reluctantly agreed. But he was pleased that a large number of his Chicago colleagues came—including Ambrose Thomas, who in response to a request from Lasker had agreed to give him a 40 percent raise, to $5,000 per year. “You’re entitled to a lot more,” Thomas had said. “Say it now, if you want more.” Lasker declined.

The couple had planned a two-week honeymoon. They went first to the Savoy Hotel in New York for several days. While in New York, though, Lasker began to get agitated about being away from his office for so long. “There was no organization,” Lasker later explained, “to keep my work going.” His anxiety rose to intolerable levels.

Flora, aware of her husband’s mounting distress, suggested that they cancel their planned ten-day trip to the Delaware Water Gap and instead return immediately to Chicago. They arrived in Chicago in mid-June, and Lasker plunged back into his work. Almost immediately, he rushed off to Battle Creek, Michigan, to take part in a strange new kind of “gold rush”: the boom in packaged breakfast foods sparked by two local entrepreneurs named C. W. Post and W. W. Kellogg.

Flora set up housekeeping at the Chicago Beach Hotel: a lakefront establishment that had been built to accommodate visitors to the 1893 World’s Fair. She lived an isolated existence. She knew no one in Chicago, and her husband traveled extensively. She made friends with some of the hotel’s residents, but she was alone a great deal of the time.

Lasker grasped the difficulty of his wife’s situation, and about six weeks into their marriage, he suggested that she go home to Buffalo for a few days. He would keep his appointments in New York and Battle Creek, and then pick her up in Buffalo. She agreed, and they went off by train in different directions.

Several days later, Lasker was working in his room at the Post Tavern in Battle Creek. The once-sleepy Michigan town had been transformed almost overnight by the national craze for packaged breakfast foods, and Lasker had positioned himself well:

I was a big figure there, because in the boom, the hotels were overrun with people who wanted to sell cotton to the manufacturers, with people who wanted to sell machinery to the manufacturers, with people who wanted jobs as salesmen, who wanted to put in processes. And among them, of course, every newspaper in America had its representatives there, and magazines and streetcar companies and billboard companies—they wanted the advertising, and they would look me up when I came.

Lasker often returned to his hotel room at night to find a stack of twenty or thirty telegrams waiting for him. On one particular night in August 1902, a friend was helping him open the telegrams. Lasker spotted one from Buffalo. Gripped by the premonition that it contained bad news, he asked his friend to open it. It was from Flora’s father. Come to Buffalo at once, it read. Flora has typhoid fever.

This was decades before antibiotics became available to treat bacterial infections. And although the dreaded typhus bacillus killed only between 10 and 20 percent of those whom it infected, it incapacitated almost all who survived. Frantic, Lasker arrived in Buffalo the next day. But there was nothing the distraught husband—then only two months into his marriage—could do for his stricken wife, already bedridden. She would not get out of bed for sixteen months.

Lasker was compelled to return to Chicago, leaving his beloved Flora behind. For more than a year, he lived alone at the Chicago Beach Hotel, visiting Buffalo almost every weekend during the long months of Flora’s illness.

Typhoid fever has an incubation period of between seven and fourteen days, so Flora almost certainly contracted the disease in Chicago.7 A disease caused by poor sanitation or poor personal hygiene, typhoid fever swept across the nation at regular intervals, often striking Chicago with particular ferocity. (In 1891, for example, the typhoid death rate in Chicago was 166 per 100,000 persons—75 percent higher than the national average.8) The city was especially vulnerable because of its high concentration of food-processing industries, as well as its woefully inadequate water and sewer systems.

Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle—which highlighted the disgraceful and unsanitary conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry and led to sweeping reforms at both the local and national levels—was still three years from publication. Chlorination of the Chicago water supply, which would finally end the threat of typhoid fever and other scourges, was still fifteen years in the future. Meanwhile, Chicagoans from all walks of life took sick. Many died, and many more were disabled.

Albert Lasker now faced thousands of dollars of unexpected medical bills. Mortified, he went back to Ambrose Thomas and asked for another raise—his second in two months. Thomas increased Lasker’s salary to an astounding $10,000 per year. This helped, but four months later, his father-in-law’s jewelry-case business failed, and Lasker found himself supporting the entire family.

Throughout this period, Albert found it achingly difficult to be separated from Flora. But as her condition worsened, it was just as wrenching to be near her: “Complications set in. The poison got into her blood, her veins were distorted to many times their natural size, her glands were all distorted; for months her legs were up in the air. At the end of 14 months, Dr. Rosewell Park operated on her for adhesions which had formed all through her legs.”

Flora’s initial bout with typhoid fever—which normally runs its course in three or four weeks—was followed by phlebitis, which brought on some of the complications that Lasker referred to: “The joints of both legs were affected, and became frozen, as in a severe case of arthritis . . . the bones of her toes and ankles had to be broken, one by one, reset, and locked in casts. She was one of the first patients in medical history to benefit from the modern orthopedic technique of traction; if this treatment had not been successful she might never have walked again.”9

At about the same time that the leg surgeries were performed, Flora told Albert that her nurse—one of the most highly regarded nurses in Buffalo—was beating and otherwise abusing her at night. When Lasker reported these accusations to her physician, he was told that Flora was hallucinating, and that he should not worry about it. Shortly thereafter, however, the nurse was caught stealing silver from the Warner house. According to Albert, she subsequently made a shocking confession: “[She] admitted in the note that she had been a dope fiend, and had been giving my wife injections of dope, and it was those injections which the doctors didn’t know about which had evidently retarded her so. The nurse was evidently one of these people who seemed sane and wasn’t sane.”

As a result of her immobility for more than a year, as well as the various complications of her illnesses, Flora gained more than seventy pounds. Even when she finally was able to get out of bed—in the fall of 1903—she was barely able to walk. Once she had been an accomplished tennis player and dancer; now she found it so painful and frustrating to shuffle around her bedroom that she preferred to stay in bed. The doctors told Lasker that unless he could get Flora walking again, the adhesions would return to her legs: “She just made up her mind she couldn’t walk. So, in desperation—I came only weekends—she said to me I had to do something about it. So I asked her to go driving, and I got a horse and buggy, and took her into the park. And I had arranged with the driver to stop by a bench . . . in a romantic little spot. It was the first time we had had alone together in 16 months.”

Lasker had the driver drive 150 feet farther down the road, taking Flora’s crutches with him:

We had a nice visit. And she said, “Oh—the carriage is down there; ask him back.”

I said, “No, Flora; you have to walk there.” And that was the first big scene we ever had. She went into hysterics in the park . . . my heart was breaking. I was only a kid of 23. This was in November, and it was getting darker, and it was cold. But I knew we were at a turning point, because the doctors had said, “You are going to have a bedridden invalid all your life, if this isn’t done now, and done drastically.”

I had told them my plan, and they had approved of it. Oh, how my heart broke . . . And the fact that her nerves had been shattered was first revealed to me then. And I remember how she had to drag herself, and at each step she upbraided me, and cried. And I remember a man coming up and wanted to beat me. He came up and my wife cried to him to make me [stop], and he . . . thought I was a brute, and grabbed me, and I shoved him aside and I said, “Let me alone! I know what I am doing! This is my wife!”10

Flora never fully regained the use of her legs. Lasker had married a young woman who moved, he said, like a fawn—full of grace, with a spring in her step. That woman was gone forever.

Gone, too, was the relatively carefree young man whom she had married. “The minute my wife took sick,” he later said, “I reached full maturity. I never had a kiddish moment.” Up to now, Lasker had never cared much for money; now he desperately had to have it. “From then on, I had to concentrate on work, and from then on, I knew I was fooling myself that I would ever get out of advertising.”

Flora—who returned to Chicago in November 1903—was determined to have children, despite medical advice to the contrary.11 As Lasker recalled: “She had this craze to have children . . . The doctors said she must not have a child, but she kept after me so much to have a child that I just felt I didn’t have to right [to say no], particularly when I was away from her almost all the time, and she was alone.”

The extreme varicosity of the veins in Flora’s legs required that she remain on her back for most of her pregnancy. This worked against her long-term recovery, and preyed on Lasker’s mind.

The baby was delivered at the family’s rented home in Woodlawn, near the University of Chicago’s campus, in September 1904. She was a healthy girl, whom her parents named Mary. Flora appeared no worse off physically, but her physician warned her that if she attempted to have another child, he would no longer attend her.

Upon returning to Chicago, Flora attempted to make friends and establish a social circle. Inevitably, conversations turned to the subject of livelihoods: What does your husband do for a living? When Flora told them that Albert was in “advertising,” her newfound friends were baffled. The concept of modern-day advertising simply hadn’t penetrated the public consciousness yet. Does he paint billboards?, one of them asked Flora. Does he wear a sandwich board?, asked another. Another invoked the disreputable realm of elixirs, painkillers, and other magic compounds: Is he connected with the patent-medicine business?12

Flora went downtown one day to open a charge account at Marshall Field. The clerk asked where her husband worked. “Lord & Thomas,” she replied. This was reference enough for the department store, and the account was opened. She recounted the episode to her husband that evening, and, combined with Flora’s stories about her friends’ reactions to his profession, it provoked a strong response in him:

Well, I had never thought of being employed by anybody, or working for anybody, and I [had] distinctly two reactions . . . One was that I was going to work all the harder and make it a business of which my wife wouldn’t be ashamed, and one which wouldn’t confuse people as to the type of man she had married. And the second thing was that never again should they ask my wife who her husband worked for . . . And of course during the time of her sickness, that wasn’t a pressing thing. But I had made up my mind that when she returned, I would be in business for myself—either as a partner in Lord & Thomas, or in some other work.

He had a strong hand to play. Only five years into his tenure at Lord & Thomas, he was one of the agency’s most valuable assets—he was generating more business than the rest of the agency’s sales force combined. Years later, he estimated that with the notable exception of the Ayer agency’s legendary Henry N. McKinney—“he occupied the first ten places, and I occupied the eleventh”—he was the most successful ad salesman in the world.

Traditionally, in the last quarter of the year, the salesmen of Lord & Thomas (and almost every other sizeable agency) fanned out across their territories in an effort to sign up their existing clients for the ensuing year.13 As Lasker made his rounds in the final months of 1903, one-year renewal contracts in hand, he met with little resistance, since his clients were thrilled with the results he had produced for them. His last stop was in Indianapolis, where he had a meeting scheduled with Frank Van Camp, the head of the Van Camp Packing Company. The meeting took place in Lasker’s room at a downtown Indianapolis hotel. After Van Camp signed his contract, Lasker asked him to accompany him to the mailbox in the hotel lobby. Van Camp, puzzled, watched Lasker drop the envelope containing the signed contract into the mailbox.

Then Lasker explained why he had wanted Van Camp to watch him put the contract in the mail: “You are the last account that Lord & Thomas has entrusted to me that [remained to be] signed up for 1904, so nothing that I can say to any of them or you can change your relationships, because you are legally bound to them. Now I feel I owe it to unfold something to you . . . I am going home tonight to resign, and [go] into business for myself.”

Lasker felt that Ambrose Thomas had made implicit promises to him that hadn’t been kept—including a partnership in the agency. He felt that all he could honorably take away from Lord & Thomas was the experience that he had gained in the previous five years. On the other hand—he said pointedly—if any of the clients whom he had just re-signed felt unhappy with Lord & Thomas at the end of the upcoming contract period, he would be happy to take them on in 1905.

Lasker also mentioned that he had discussed his plans with a senior colleague, Charles R. Erwin, but with no one else at Lord & Thomas. In truth, his discussions with Erwin were far advanced. Lasker “dreaded” going into business alone; he wanted a partner to share the risk, and he believed Erwin could lend credibility to the new venture: “He was a man of fine appearance, who could give confidence to anyone. Lovely shock of hair . . . And he was a good deal older than I was, [and] he understood a great deal of figures. I still had the feeling that the head of the house had to do what Mr. Lord did—open the mail, go to the bank if we needed it. I never had any contact with that end, so it all seemed very important to me.”

Lasker offered Erwin a fifty-fifty partnership in his proposed new agency—and Erwin immediately accepted. “That is the only thing I ever did in business of which I am ashamed,” he later admitted. “I don’t believe that I had the right to win one of my coworkers away.”

In response to these revelations, Frank Van Camp volunteered very little.

The next morning, back in Chicago, Lasker approached Ambrose Thomas’s secretary, Kate Grady, and asked to see Thomas. Grady told Lasker that Thomas was in a meeting with Mr. Van Camp and could not be disturbed.

It is difficult to imagine the anxiety Lasker must have felt upon hearing this news. That anxiety must have increased exponentially, hour by hour, as Thomas and Van Camp remained behind closed doors all morning. Finally, Thomas sent word to Lasker to meet him at the bar in Chicago’s Wellington Hotel at the end of the day.

Standing at the bar, drink in hand, Thomas revealed that Frank Van Camp had called an emergency meeting, taken the train to Chicago, and repeated everything that Lasker had said to him. Moreover, Van Camp had informed Thomas that he fully intended to jump to Lasker at the end of the upcoming year, and that he suspected that every other one of Lasker’s accounts would do the same. The only thing for Thomas to do, Van Camp said—the only way to hang on to Lasker and his accounts—was to make Lasker a partner.

Thomas told Lasker that he had decided to take Van Camp’s advice and make both Lasker and Erwin partners in the firm. He had already approached cofounder and partner Daniel Lord and induced him to resign to make room for Lasker and Erwin. They had put a value of $200,000 on the business, which meant that Lord’s half-interest could be acquired for $100,000, with $30,000 down. Stunned, Lasker accepted the proposal.14

Then came the hard part: finding $30,000. Lasker scraped together $10,000 in loans from friends and family members—not including his father—and Erwin came up with $5,000.15 This left them $15,000 short. In an astounding display of bravado, Lasker then demanded that Ambrose Thomas make him a gift of the remaining $15,000, arguing that going into business on his own would cost Lasker far less than $15,000, and that Thompson was trading a more or less inactive partner (Lord) for two active partners (Lasker and Erwin).

On February 1, 1904, Albert Lasker became a one-quarter partner in Lord & Thomas. His peculiar road to partnership created tensions between himself and his mentor. One Saturday night in the early months of 1906, for example, Lord & Thomas held a firmwide dinner at the Stratford Hotel. At the end of the evening, Lasker rose and toasted Ambrose Thomas. “Whatever the business is,” he proclaimed, “it owes to Mr. Thomas, because of his tolerance, and the fact that he gives everyone opportunity. The remarkable progress we are making is through the confidence and encouragement he lends to all of us.”16

After the dinner, Charles Erwin suggested that the three partners head down to the hotel bar for a nightcap. Even though it was now past midnight, Lasker and Thomas agreed. After downing several drinks, Lasker recalled, Thomas suddenly addressed him in the “meanest tone” that the elder man had ever used on him:

“Why did you make that talk tonight?” Thomas demanded. “You know you never meant a word of it.”

Lasker, “hurt to the quick,” protested strenuously that he had. And then he fought back:

Mr. Thomas, ever since we started the new firm, you have changed. Instead of being to me, in a personal way, like you were before, you have done nothing but be offensive. You have done nothing but humiliate me with myself, and I can’t stand another humiliation.

This is Saturday night. I’ll not be down to work on Monday. You can have my stock. This time, I’m going to start up in business across the street. I can’t stand it anymore. I owe you a great debt, but I don’t owe you my self-respect.

At this point, Thomas turned to Erwin and demanded that he back him up. Instead, the normally placid Erwin rose to the defense of his younger partner. If Lasker quit, Erwin concluded, he would be out the door with him.

Thomas backed down immediately. He apologized to Lasker, and sometime after 2:00 a.m.—tired, tipsy, but with the hatchet mostly buried—Thomas and Lasker boarded the same Illinois Central train to return to their homes in Woodlawn.

![]()

For the next six months or so, into the late fall of 1906, Thomas was wary around his junior partner. Lasker later remembered this interlude as the most difficult period in his relationship with Thomas, even worse than the months of abuse that had preceded it: “He tried to show his extreme[ly] tender feeling for me, until I could no longer be natural in the office, and hated going to the office . . . That isn’t what I wanted from Mr. Thomas. He always was the boss, and the chief, to me. I was perfectly willing for him to order me to do something. I even preferred to have him cross with me. I felt unnatural.”

Once again, Lasker decided to leave the firm. He resolved to hand over his interest in Lord & Thomas to his senior partner and—acting on his long-deferred dream—go into the newspaper business. The best way to make his break, he concluded, was to ask Thomas if they could walk to work together the next morning: November 10, 1906. On that walk, Lasker would quit. The pretext that Lasker gave to Thomas over the phone was that he wanted to show him a red rug that he had seen that day at Carson, Pirie, Scott on State Street. Lasker proposed to buy the rug to decorate Thomas’s new office, he said, but wanted to make sure Thomas approved of the choice. Could they stop at the furniture store on the way into work, Lasker asked? Thomas agreed.

From Lasker’s point of view, the walk couldn’t have gotten off on a worse note. Thomas told Lasker that the younger man needed to take some time off. “No one can work the way you are working,” he said solicitously. Then he suggested that Lasker take Flora, their two-year-old daughter Mary, and a nurse to Japan for six months, at the firm’s expense. Lasker had always dreamed of visiting Japan.

Presented with this extraordinarily generous gesture, Lasker lost his resolve. Curtly, he told Thomas he didn’t need a vacation.

Now they arrived at Carson, Pirie, Scott. They took the elevator to the rug department on the seventh floor, and sat on a sofa while a salesperson went off to retrieve the red rug. Thomas again urged Lasker to take an extended vacation. “If you don’t take this vacation,” the fifty-five-year-old Thomas continued, addressing his twenty-six-year-old partner, “we will bury you by the time you are thirty-six.”

Those were the last words Thomas ever uttered. At that moment, he gasped for air, and fell dead onto Lasker’s shoulder, the victim of a massive heart attack.17 A physician who happened to be nearby tried unsuccessfully to revive the stricken executive, while members of the sales force threw up a screen to conceal the scene from curious onlookers. Lasker wandered back home while the store manager took responsibility for notifying Thomas’s family. “I couldn’t take any part in it,” Lasker later admitted.18

In the wake of Thomas’s death, there was no way Lasker could abandon Lord & Thomas. By the terms of the partnership agreement, Thomas’s interest in the firm now was divided equally between the two surviving partners.19 At the age of twenty-six, Lasker was the leader and half-owner of the second-largest advertising agency in the United States, with billings in excess of $3 million. The “Lord & Thomas” name remained unchanged. (Lasker wanted to take advantage of the agency’s accumulated goodwill, and even at this early age, he saw advantages in adopting a low profile.) Charles Erwin became the new president of the company, but no one was confused about who was running the firm.

The business pressures that Lasker was already finding onerous before the fall of 1906 now became unbearable. And now, pressure began mounting from another direction, as Flora continued to suffer from a range of ailments. Early in 1907, her condition worsened, with the glands in her neck swelling to an alarming degree. Phlebitis, her continuing affliction, was not well understood, but it was known to be a sudden killer.

In April 1907, Lasker—heretofore a sometimes fragile but generally high-functioning individual—experienced a total collapse. He looked at his world and couldn’t stop crying:

I had a terrible breakdown . . . I just couldn’t work . . . I couldn’t keep going anymore . . .

My wife, of course, was never well—she was an invalid all through our 35 years of married life—and this was a tremendous burden on her, in her condition, because I could do nothing but cry. Literally. I lost control to do anything but cry.

I had done nothing but work from the time I was 12. I married, and my wife was ill, and I never had taken off any time to play, excepting the type of play that did me hurt. And the reason I did that type of play, I imagine, was that it was so digested, concentrated, and I could do a lot of [it] in a hurry.

I just had a good old-fashioned breakdown. And in fact, my life ever since has been a struggle from breakdowns, because I never fully—I always say I got over all my breakdowns except my first one.20

Lasker operated at a high energy level. He was frequently expansive, irritable, highly verbal, intensely creative, and insomniac—all symptoms of a condition that today would be called hypomania. He never ascended to the level of mania that is generally associated with manic depression, or—again in today’s vocabulary—a bipolar I disorder, although he sometimes behaved erratically, especially under the influence of alcohol.21 Most likely, he was afflicted by a bipolar II (or “unipolar”) disorder.

Recent research suggests that there is an increased risk of bipolar II disorder among people whose family members suffer from the disorder. Eduard Lasker, Albert’s uncle, clearly had depressive episodes. Morris, too, may have experienced depressions; his rollercoaster financial affairs may have had their root, in part, in some sort of affective illness.

Finally, that diagnosis is supported by Lasker’s age when the ailment overtook him. Bipolar I—the depression that is accompanied by wild, manic excess—usually first manifests itself in the teenage years, while the unipolar form of the illness often stays masked until the mid- or late twenties. Lasker was stricken at age twenty-seven. Abraham Lincoln, whose depressive symptoms closely resemble Lasker’s, was twenty-six when his first attack overtook him. Both Lasker and Lincoln had their second major breakdown a half-decade after their first.22

In both Lincoln’s and Lasker’s case, the ailment was episodic. “Most people who have manic-depressive illness are, in fact, without symptoms (that is, psychologically normal) most of the time,” writes psychiatrist Kay Redfield Jamison.23 Jamison also puts forward the provocative hypothesis that bipolar illness is often bound up with creativity. Although her study of madness and creativity focuses on artists, it is intriguing to examine Albert Lasker (and indeed, Abraham Lincoln and others outside the “artistic” realm) through this same lens: “It is the interaction, tension, and transition between changing mood states, as well as the sustenance and discipline drawn from periods of health, that [are] critically important; and it is these same tensions and transitions that ultimately give such power to the art that is born in this way.”24

Lasker assumed that he had succumbed to the pressures of his life. Those pressures surely were mounting in the winter of 1906 and spring of 1907. But recent psychological research suggests that the search for causality in depression may be fruitless. Certainly, having a surrogate father die in one’s arms and being forced to watch a beloved wife deteriorate were crushing burdens. Most likely, though, Lasker’s illness arrived on its own timetable. And now Lasker—the man who did everything in a hurry, in “concentrated” form—was immobilized.

No effective therapies for depression existed at that time. Sigmund Freud’s “talking cure” was known only to a small medical community and was still highly controversial. Electroconvulsive therapy didn’t come into common usage until the 1930s, and the efficacy of lithium and other drugs in treating mental illness remained unknown until the 1950s. In 1907, the only option for an individual who couldn’t stop crying was to retreat from the world.

So that is what Lasker did. Putting the business in the hands of Charles Erwin, Lasker left for Europe with Flora, in search of peace of mind for himself and expert medical care for his wife.

The Laskers’ first stop was a sanatorium on the edge of Germany’s Black Forest. The ruhe (“retreat”) was owned by a cousin—a physician also named Albert Lasker. He had built several guesthouses on the property, where he offered a restful environment for people who had suffered nervous breakdowns. The American Lasker found the place congenial enough, but far from therapeutic: “I just rested in bed and took the baths, and walked through the forest, do you see? And then, because I wanted to get my money’s worth, we did considerable traveling on the Continent, which sent me home not much recovered from what I had started.”

By now, Lasker had been away from the office several months, and his anxiety was mounting. The Laskers, still suffering from their respective illnesses, cut short their trip and returned to Chicago.

![]()

Perhaps the question is not why Albert Lasker crumpled in the spring of 1907, but rather, how he held up as long as he did.

From the outset, his mental health was fragile. After relocating to Chicago, he was isolated—in part by his brilliance, and in part because he had physically removed himself from everyone he loved and who loved him. Leaving Galveston, he not only cut himself off from parents to whom he felt closely bound, but also denied himself a gradual transition to adulthood. Overnight, he was thrown into an adult world, largely populated by rootless men and heavy drinkers. He drank heavily himself, further insulating himself from the world.

Lasker was deeply introspective: a trait that sometimes helped him. Seeing self-destructive tendencies in himself, for example, he found and methodically courted a mate. But in an astoundingly cruel twist of fate, Flora became permanently disabled less than two months after their marriage. The financial burdens, psychological upset, and guilt imposed by her illness were staggering.

The melodramatic death of Ambrose Thomas pushed him closer to the edge. Now he was running the business that he had planned to run away from. He was trapped—by the business and by the grinding financial needs of his family. By April 1907, Lasker couldn’t stop crying.

It was only the first of many such episodes, which—on their own schedule—broke into his world and stole him away.