Chapter Six

![]()

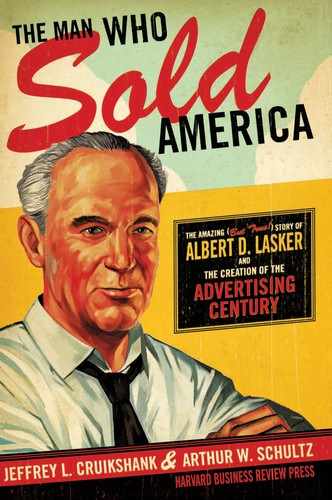

The Greatest Copywriter

![]()

FOR LORD & THOMAS, and for Albert Lasker in particular, Frank Van Camp—the head of the Indianapolis-based Van Camp Packing Company—was an extremely important client. Van Camp’s confidence in his young account manager had led directly to a major shake-up at Lord & Thomas, to Daniel Lord’s abrupt retirement in 1904, and to Lasker getting his original ownership stake in the agency.

Van Camp was also a demanding client. When the gifted but erratic John E. Kennedy, copywriter for the Van Camp account, left Lord & Thomas in 1906, Van Camp insisted that Lasker come up with a writer who was as good as Kennedy—or better. This was a formidable challenge, and Lasker didn’t know how to meet it.

The Van Camp Packing Company was founded by Gilbert C. Van Camp in 1862. Gilbert and his wife Hester ran a small store in Indianapolis, selling fruits and vegetables that they canned themselves. Gilbert, an accomplished tinsmith and tinkerer, gradually built up the business, improving his canning techniques and constructing one of the nation’s first cold-storage warehouses.1 Gilbert’s and Hester’s three sons—Frank, George, and Cortland—all joined the business, although Cortland soon departed to start a hardware company. Although tinned foods had been produced for nearly a century, cost and quality-control problems restricted their use mainly to the military. The perfection of new canning techniques—especially ways of preventing solder from getting into the food—and the advent of new distribution channels opened up unprecedented opportunities in the 1890s. Now, food companies like Franco-American and H.J. Heinz began producing an array of canned goods aimed at consumers.

In 1894, George figured out a way to can pork and beans in tomato sauce, thus broadening the company’s base beyond its standard vegetable, chicken, and turkey products.2 Frank, meanwhile, put a half-dozen salesmen on the road to push Van Camp canned goods, and commissioned some rudimentary advertising.3 Also in 1894, the Joseph Campbell Soup Company, headed by the visionary John T. Dorrance, introduced a line of canned condensed soups. Dorrance invested $5,000 in streetcar ads in 1899; the results were so gratifying that the company increased its ad budget by 50 percent within six months. By 1905, Campbell’s was selling 20 million cans of soup a year.4

Albert Lasker wrote some of Lord & Thomas’s early copy for Van Camp. That work—including the “Ludwig and Lena” campaigns, which featured cartoons of two children in Hansel-and-Gretel outfits holding cans of pork and beans—was forgettable, at best. (“It’s the intangible, subtle element which has taught you to think Van Camp whenever you think of pork and beans,” the text of one ad ran.5) “I confess that I was responsible for Ludwig and Lena,” Lasker later said ruefully, “who prated some kind of nonsense in the Van Camp advertising.”6

Together, Kennedy and Lasker helped solved a knotty problem for Van Camp. Just after the turn of the century, the company had gone into the evaporated-milk business. Evaporating (or condensing) milk meant putting raw milk into large vacuum pans and removing two-thirds of the water. This condensation process, which involved high temperatures, also sterilized the milk and prevented it from spoiling. Housewives could use the product undiluted as a substitute for cream, or could add two pints of water to turn it back into an approximation of milk.7

Kennedy started searching for ways to market Van Camp’s milk, which was generally a weak competitor, trailing Borden’s and other leading brands. He came up with an ad that featured a bold headline—Now a cow in your pantry—and a picture of an eye-catching creature: a cow with Van Camp milk cans for its body and legs, can openers for horns, and a serving spoon for a tail.8 Even Lasker, who generally disapproved of illustrations (because they were a distraction from the copy), acknowledged the power of this concept.

Lord & Thomas persuaded Van Camp to run test campaigns in Peoria, Indianapolis, and Jacksonville, and these tests revealed a problem. Van Camp’s Evaporated Milk—like its competitors—didn’t taste very good. Housewives, seduced by the prospect of a “cow in their pantry,” were willing to try Van Camp’s tinned milk, but most disliked the scalded aftertaste.

Lasker and Kennedy first persuaded Van Camp to change the name of its product from “evaporated milk” to “sterilized milk.” Next, they proposed that Van Camp simply own up to the slightly objectionable taste of the product and recast it as a virtue. As the Lord & Thomas case history—probably dictated by Lasker—later put it: “We tried to find something that would nicely describe that scalded taste, and we finally hit upon, ‘Be sure and taste the milk and see if it has got the almond flavor. If it has not the almond flavor, it is not the genuine.’”9

“It is like telling an Aladdin fairy tale,” the account history bragged, “to tell you how it went.”10 Van Camp quickly displaced Borden as the leading evaporated milk in key markets like New York City. “No one else had a chance with milk [in New York],” one of Lasker’s business associates later commented, “while [Lasker] was carrying on his campaign.”11 Van Camp’s overall sales soared 30 percent between 1904 and 1905.12

With this success, of course, came greatly increased billings for Lord & Thomas. Frank Van Camp, Lasker recalled, “had made up his mind that the world was his if he advertised well, and widely.”13

The problem for Lasker now was that the mercurial John E. Kennedy had departed, and Frank Van Camp knew it. The Indianapolis packer wanted to put substantial resources into marketing his company’s old standby: pork and beans. Up to this point, he had restricted his pork-and-bean advertising to selected magazines, assuming that there was only a limited market for the product. Now he was willing to double or even triple his advertising dollars—in fact, he was willing to make the huge leap to national newspaper advertising of pork and beans—but only if Lasker could find an outstanding copywriter to replace Kennedy.

“So I was up against it,” Lasker later recalled.

Sometime in 1907 (as Lasker told it), he was riding on a train. Seated across from him was Cyrus H. K. Curtis, the powerful founder of the Curtis Publishing Company, whom Lasker considered to be a shrewd judge of advertising. A former ad salesman, Curtis had launched a weekly magazine, the Tribune & Farmer, in 1879. His wife Louisa’s popular column in that periodical led to a spin-off in 1883—the Ladies’ Home Journal. In 1896, Curtis bought a broken-down publication called the Saturday Evening Post with ad revenues of less than $7,000 per year; by the time he was sharing a train compartment with Albert Lasker, the Post was bringing in $1 million a year.14

Lasker at first didn’t recognize the celebrated publisher, who was partially concealed behind his newspaper. After they finally exchanged greetings, Curtis told Lasker that he had just read an extremely effective ad in his newspaper. “Lasker,” Curtis supposedly said, “I am just about to order a bottle of beer as a result of an advertisement that I read, and you ought to go get the man who wrote that advertisement for your advertising business.”15

Lasker knew that Curtis was a near-teetotaler who didn’t permit the words “beer” and “wine” to appear in his Ladies Home Journal.16 Now, here he was, heading off to the bar car in search of a beer. Which beer, exactly? Lasker looked at the ad that had caught Curtis’s eye. “Poor Beer vs. Pure Beer,” the headline read. It was an ad for Schlitz—a second-tier competitor to mighty Anheuser-Busch of St. Louis, which happened to be a Lord & Thomas account. “The beer that made Milwaukee famous,” read the tag line below the prominent Schlitz logo. Lasker read the copy with interest:

Both cost you alike, yet one costs the maker twice as much as the other. One is good, and good for you; the other is harmful. Let us tell you where the difference lies.

Poor beer, the copy claimed, involved “no filtering, no sterilizing, [and] almost no aging, for aging ties up money.” Pure beer, by contrast, “must be filtered, then sterilized in the bottle,” and must be “aged for months, until thoroughly fermented, else it causes biliousness.”17 Schlitz’s product was a pure beer, and therefore a “healthful” beer. One proof was the Schlitz brewery, with its plate glass windows that gave visitors a clear view of the brewing process. “You’re always welcome to [visit] that brewery,” the ad concluded cheerily, “for the owners are proud of it.”

Lasker was amused and intrigued. Without exactly saying so, the copywriter had effectively accused Schlitz’s competitors of being unsanitary and inducing in beer drinkers the nasty-sounding “biliousness.” The copy had suggested that Schlitz welcomed scrutiny of its brewing process in a way that other brewers could not. Schlitz, the beer that made Milwaukee famous, had nothing to hide!

Upon returning to Chicago, with the urgent demands of Frank Van Camp very much in his mind, Lasker began making inquiries: Who is writing the Schlitz campaign? The answer came back: an odd duck named Claude C. Hopkins.

![]()

Much of what is known about Claude Hopkins’s early years comes from My Life in Advertising, his charming and maddening autobiography. Written in 1927 and today considered a classic, this slim volume’s appeal grows out of its idiosyncratic authorial voice:

I do not know the reactions of the rich. But I do know the common people. I love to talk to laboring-men, to study housewives who must count their pennies, to gain the confidence and learn the ambitions of poor boys and girls. Give me something which they want and I will strike the responsive chord. My words will be simple, my sentences short. Scholars may ridicule my style. The rich and vain may laugh at the factors which I feature. But in millions of humble homes the common people will read and buy.18

At the same time, My Life In Advertising frustrates because it is so remarkably devoid of facts. Perhaps Hopkins had no records at hand as he sat down to write. Or perhaps he saw no particular advantage in making it easy for his readers to connect the dots in ways that might reflect unfavorably on him or his family. In any case, it would be hard to find another autobiography with such a shortage of people, places, and dates.

We know from other sources that Hopkins was born on April 24, 1866.19 He grew up in Hillsdale, Michigan, until his father—Fernando F. Hopkins, a college-educated printer—bought a partial interest in a weekly newspaper based in Ludington, Michigan, which Hopkins described only as a “prosperous lumbering city.”

In his writings, Claude Hopkins claimed that his mother was “left a widow” when Claude was ten years old, but the sketchy available evidence suggests that Fernando may have abandoned the family. In either case, for the next decade, Hopkins struggled alongside his mother to keep the family housed and fed. He sold his mother’s silver polish door-to-door. He cleaned two schoolhouses at the beginning and end of each school day. He delivered the Detroit Evening News to sixty-five houses before dinner. On Sundays he worked as a church janitor, and during summer vacations he did farm work. For the rest of his life, even after becoming an extraordinarily wealthy man, he feared slipping back into the desperate poverty of his youth. As a result, he maintained a seven-day-a-week, twelve-hour-a-day work regimen: “If I have gone higher than others in advertising, or done more, the fact is not due to exceptional ability, but to exceptional hours. It means that a man has sacrificed all else in life to excel in this one profession. It means a man to be pitied, rather than envied, perhaps.20

Sometime around 1883, Hopkins graduated from high school and became a minister and teacher. Neither profession satisfied his aching ambition. Perhaps a year later, he enrolled at Swensburg’s Business College in Grand Rapids, which he later dismissed as a “ridiculous institution.”21 But it led him to a job keeping the books—and sweeping the floors, and cleaning the windows—at the nearby Grand Rapids Felt Boot Company.

In the course of what may have been a year at the Felt Boot Company, Hopkins met Melville R. Bissell, president of the Bissell Carpet Sweeper Company. In 1876, Bissell had patented his carpet-cleaning device—which he had invented to lift sawdust off the rugs in the small crockery store that he and his wife operated—and by 1883, he was constructing his first factory. Bissell offered Hopkins a bookkeeping job at his new factory for substantially more money than he was making at the boot factory.

Once at Bissell, Hopkins again went looking for opportunity. One day, a mediocre draft for a new brochure arrived at the factory, written by a celebrated advertising man who had not bothered to learn much about carpet sweepers. Hopkins asked for the chance to rewrite the text on his own time. His skeptical superiors said yes, and Hopkins beat out the celebrated out-of-towner with a much-improved text.

He then began figuring out ways to drum up demand for his company’s product. First, he pushed carpet sweepers as Christmas presents—a notion that had not occurred to anyone before—and generated a staggering one thousand orders through a combination of letter writing and store displays. Next, he hatched a scheme to offer Bissell Carpet Sweepers in a dozen different woods, “from the white of the bird’s-eye maple to the dark of the walnut, and to include all of the colors between.”22 Using both the carrot and stick with the company’s dealers—and again overcoming the deep skepticism of his colleagues in Grand Rapids—Hopkins sold 250,000 exotic-woods carpet sweepers in three weeks.

In the parlance of the day, Hopkins had become a “scheme man,” and a marketing talent like this would not remain in Grand Rapids for long. Sometime in 1891, when Albert Lasker was still an eleven-year-old boy down in Galveston, Lord & Thomas got in touch with the dazzling young talent up in Grand Rapids and offered him a job. As Hopkins recalled:

They had a scheme man named Carl Greig, who was leaving them to go with the Inter Ocean to increase the circulation. Lord & Thomas, who had watched my sweeper-selling schemes, offered me his place. The salary was much higher than I received in Grand Rapids, so I told the Bissell people that I intended to take it. They called a directors’ meeting. Every person on the board had, in times past, been my vigorous opponent. All had fought me tooth and nail on every scheme proposed. They had never ceased to ridicule my idea of talking woods in a machine for sweeping carpets. But they voted unanimously to meet the Lord & Thomas offer, so I stayed.

Not for long, however. Probably later in 1891, Hopkins saw an ad for a position as advertising manager at Swift & Company, in Chicago. He got the job and moved to Chicago, only to find that the huge packing firm viewed his profession—and by extension, him—as a necessary evil. Founder Gustavus Franklin Swift, a transplanted Yankee from Massachusetts who had founded the packing company a half-decade earlier, regarded business as a form of warfare and advertising as an expensive distraction from the business of war-making. As Hopkins put it: “I was more unwelcome than I supposed. Mr. G. F. Swift, then head of the company, was in Europe when I was employed. It was his first vacation, and he could not endure it, so he hurried back. When told that I was there to spend his money, he took an intense dislike to me, and it never changed.”23

Hopkins’s first big challenge was to promote a Swift product called Cotosuet, which was a mixture of cottonseed oil and beef suet, packed in tin pails and used as an inexpensive substitute for lard and butter. It was no different from, or better than, or cheaper than, its entrenched competitor, Cottolene. Hopkins struggled to come up with a way to push Cotosuet on an indifferent public. He soon settled upon a scheme to bake the “world’s biggest cake” using Cotosuet, and put it on display in a new department store that was about to open in downtown Chicago. Traffic stalled on State Street as huge crowds flocked to behold the monstrous dessert. Over the course of a week, more than 100,000 people climbed four flights of stairs to see it. They were encouraged to try a sample and to win prizes by guessing the weight of the cake—but only after buying a pail of Cotosuet. “As a result of that week,” Hopkins wrote, “Cotosuet was placed on a profit-paying basis in Chicago.”24

Next, apparently in 1895, Hopkins left Swift and began a six-year stint in Racine, Wisconsin, working for Dr. Shoop’s Family Medicines—the manufacturer of patent medicines that subsequently employed John E. Kennedy.25 In later years, Hopkins looked back with some embarrassment on his efforts to promote remedies that were either ineffective or dangerous, but he never stopped thinking of that experience as the “supreme test” of the copywriter’s skills. “Medicines were worthless merchandise,” he wrote, “until a demand was created.”26 Hopkins came up with various “pull-through” schemes to compel druggists to carry Dr. Shoop’s elixirs.

In 1902, Hopkins was contacted by Chicago-based entrepreneur Douglas Smith, who had made a small fortune manufacturing the Oliver typewriter. While building a typewriter factory in Toronto sometime around 1898, Smith had learned of a supposed germicide—Powley’s Liquified Ozone—that came highly recommended by local users. Smith picked up the product for $100,000, changed its name to “Liquozone,” and started marketing his new product through the newly formed Liquid Ozone Company, which he headquartered in Chicago.

Four years and four ad managers later, he was desperate to find a way to sell the stuff. Hearing that Hopkins was the best scheme man and copywriter in Chicago, Smith approached him with an unusual proposition: If Hopkins would sign on with Liquozone and agree to work for no salary, Smith would give him a quarter of the company. After a great deal of anguish about leaving his comfortable perch in Racine for a situation where he would be living off his savings while trying to rescue a dying company, the deeply conservative Hopkins took the plunge. In February 1902, he moved to Chicago and began promoting another product nobody much wanted.

“Night after night I paced Lincoln Park,” Hopkins wrote, “trying to evolve a plan.”27 The plan he came up with resembled one he had developed earlier for Dr. Shoop. The company would offer a fifty-cent bottle of its germicide free to anyone who responded to a newspaper ad. (Getting the consumer to ask for the sample was a key part of many schemes devised by Hopkins.) Liquozone would send a coupon redeemable at a local druggist, where the recipient of the free sample would also be offered a money-back guarantee on five $1 bottles of the product. Beginning with a test market—Hopkins believed fervently in testing his “schemes” before asking his client to plunge—the company found that requests for free samples cost 18 cents to generate. Thirty days later, it was clear that the average coupon redeemer was spending 91 cents on Liquozone. Over the next three years, Smith and Hopkins gave away 5 million free samples. By 1904, Liquozone was advertised in seventeen languages and sold around the world, and Hopkins was a rich man.

Here the chronology again starts to get tangled. Beginning sometime in the early years of the twentieth century—probably while he was still with Dr. Shoop’s—and continuing through his days at Liquozone, the peripatetic Hopkins moonlighted as a freelance copywriter for the Chicago-based J. L. Stack Advertising Agency. Stack was a Lord & Thomas–trained ad man who, around the turn of the century, had gone into competition with his former employers.28 He recognized the copywriter’s formidable talent, and put him to work with a number of key clients, including Montgomery, Ward & Co., and—notably—Schlitz.

Hopkins toured the Schlitz brewery in Milwaukee and was impressed. When he asked his clients why they didn’t boast of their pure water, their white-wood-pulp filters, their filtered air, their four separate washings of their bottles, the Schlitz executives responded that everyone brewed beer in this way. No matter, said Hopkins. If you tell a good story, and tell it first, it will be your story:

So I pictured in print those plate-glass rooms and every other factor in purity. I told a story common to all good brewers, but a story which had never been told. I gave purity a meaning . . .

Again and again I have told common facts, common to all makers in the line—too common to be told. But they have given the article first allied with them an exclusive and lasting prestige.

That situation occurs in many, many lines. The maker is too close to his product. He sees in his methods only the ordinary. He does not realize that the world at large might marvel at those methods, and that facts which seem commonplace to him might give him vast distinction.29

On the strength of Hopkins’s efforts to “give purity a meaning,” Schlitz jumped from fifth in sales to a near-tie with mighty Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis.

![]()

On the day that Albert Lasker read Claude Hopkins’s Schlitz ad on the train in 1907, Hopkins was no longer working for Liquozone. In fact, for the first time since he was ten years old, he was not working at all.

In My Life In Advertising, Hopkins says that he signed on with Doug Smith’s company in 1902 and worked there for five years—in other words, almost up to the day Lasker spotted him. We also learn that he had a breakdown toward the end of those five years, which forced him to consult a doctor in Paris. The French doctor told Hopkins that the only thing that could save him would be for him to go home and rest. Hopkins (who lived out of hotels, and didn’t have a home) retreated to the sleepy town of Spring Lake, Michigan, near the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, where he had worked as a farmhand decades earlier. There, he spent three months “in the sunshine, sleeping, playing, and drinking milk.”30

What Hopkins does not mention in his autobiography, and which surely must have been a contributing factor to his breakdown, is a series of events that surely represented calamity to the one-quarter owner of the Liquid Ozone Company. The disaster kicked off on October 7, 1905, when Collier’s magazine carried an article entitled “The Great American Fraud” by an enterprising young writer named Samuel Hopkins Adams. Adams was one of America’s first investigative reporters, and he was extremely good at his trade. “This is the introductory article to a series which will contain a full explanation and exposure of patent medicine methods, and the harm done to the public by this industry,” Adams began, “founded mainly on fraud and poison.”31

At the end of the article, Adams apologized in advance that he would not be able to expose all of the vile potions and elixirs that were out there, bilking Americans of some $75 million per year and discouraging them from seeking legitimate medical help. There were simply too many of them, and “many dangerous and health-destroying compounds will escape through sheer inconspicuousness.” But Adams promised he would go after the worst offenders in each of several categories: the alcohol stimulators, the opium-containing soothing syrups, the headache powders, and the “comparatively harmless fake, as typified by that marvelous product of advertising and effrontery, Liquozone.”32

A subsequent installment in the series was devoted to Liquozone. In his attack, Adams combined wit, scorn, and science in roughly equal measures. A typical passage mocked the Liquid Ozone Company’s claims that their product consisted of “liquid oxygen”: “Liquid oxygen doesn’t exist above a temperature of 229 degrees below zero. One spoonful would freeze a man’s tongue, teeth, and throat to equal solidity before he ever had time to swallow. If he could, by any miracle, manage to get it down, the undertaker would have to put him on the stove to thaw him out sufficiently for a respectable burial.”33

In fact, as Adams compelled the Liquid Ozone Company to reveal, their product was 98 percent water, with trace amounts of sulfuric and sulfurous acids. Collier’s paid the Lederle Laboratories in New York to test Liquozone’s efficacy against anthrax, diphtheria, and tuberculosis (all of which supposedly were warded off by the internal or topical use of Liquozone). In every case, all of the test animals—those treated with Liquozone and those not treated—contracted diseases.

Nor did the senior executives of the Liquid Ozone Company escape Adams’s scourging. Douglas Smith was dismissed as a “promoter” with a “keen vision for profits.” Adams called Claude Hopkins the “ablest exponent of his specialty in the country,” and admitted that he might not be the most culpable in a generally guilty group:

An enormous advertising campaign was begun. Pamphlets were issued containing testimonials and claiming the soundest professional backing. Indeed, this matter of expert testimony, chemical, medical, and bacteriologic, is a specialty of Liquozone. Today, despite its reforms, it is supported by an ingenious system of pseudoscientific charlatanry. In justice to Mr. Hopkins, it is but fair to say that he is not responsible for the basic fraud; that the general scheme was devised and most of the bogus or distorted medical letters arranged before his advent.34

This was a public-relations disaster of the first order, and it kept getting worse. No matter that Hopkins believed in Liquozone—and believed that its use had saved his daughter’s life. In response to the Collier’s revelations, North Dakota banned the sale of Liquozone. So did San Francisco and Lexington, Kentucky. In 1906, partly owing to the public outcry caused by Adams’s articles, Congress passed the federal Food and Drugs Act, which compelled manufacturers to state exactly what was in the preparations they were selling to the public.

It is not surprising, then, that Claude Hopkins called his five years with Liquozone “strenuous,” and that by the spring of 1907, he was on a milk diet along the quiet shores of Spring Lake.

![]()

Albert Lasker was well aware of the troubles plaguing the Liquid Ozone Company. In fact, he had had a similar experience. Early in his tenure at Lord & Thomas, the agency represented a patent-medicine concern called the Kalamazoo Tuberculosis Remedy Company. The company was exposed as a fraud, and as soon as Lasker took the reins at Lord & Thomas, he steered the agency out of the patent-medicine business.35

Lasker had followed the Liquozone campaigns carefully, going so far as to cut out a particularly effective ad and study it “a hundred times.”36 He admired the company’s clever use of coupons, which made Lasker think of the Liquozone writer as a “kindred spirit.”37 Now, as he made his discreet inquiries in 1907, he discovered that the same person—Claude C. Hopkins—was behind both the Schlitz ads and the Liquozone campaigns.38

He learned this from a friend, Stephen Hester, who owned a small stake in Liquozone. Lasker asked Hester how he might persuade Hopkins to come work for Lord & Thomas. Hester—an invalid who rarely left his Chicago hotel rooms and had both the time and the inclination to conspire with Lasker—came up with an elaborate ruse for recruiting Hopkins, whom he regarded as “a quiet man, a highly sensitive man, a man who is stingy with money in small things.”39

Hopkins, Hester explained to Lasker, had spent nearly his whole life in advertising. By most accounts, he was the greatest advertising man alive—and yet, he was now “disgraced, and disheartened.” And to further complicate things, Hopkins was worth something like $1 million, so he didn’t need to work. Rumor had it that Hopkins was going to get out of business and become an author.40

Hester proposed to introduce Lasker to Hopkins at lunch. Lasker would tell Hopkins about his problems with Frank Van Camp, and explain that he would consider it a great personal favor if Hopkins would compose a few ads just to get the new campaign started. Hester strongly advised Lasker not to offer to pay him. Instead, Hester said, he should offer to buy a new electric automobile for Hopkins’s wife. “His wife wants an electric automobile for $2,700,” Hester told Lasker, “and he won’t give it to her. This will solve the most pressing problem he has.” Lasker agreed to the scheme.

He may have been surprised, on the day of the luncheon, at the relatively unprepossessing manner and appearance of his man. Slightly foppish, with a thin mustache and protruding front teeth, Hopkins spoke with a lisp, so that when he introduced himself as “C. C. Hopkins,” it came out as “Thee-Thee.” (This became his nickname around the office for the next seventeen years, although to his face, Thee-Thee was always addressed as “Mr. Hopkins.”) Lasker followed Hester’s script to the letter, and Hopkins agreed to jumpstart the Van Camp campaign.

Hopkins’s account of that lunch adds some interesting details. He recalled Lasker showing him a contract for $400,000 from the Van Camp Packing Company, contingent on satisfactory copy being submitted to Frank Van Camp. According to Hopkins:

Mr. Lasker said, “I have searched the country for copy. This is the copy I got in New York, this in Philadelphia. I have spent thousands of dollars to get the best copy obtainable. You see the result. Neither you nor I would submit it. Now I ask you to help me. Give me three ads, which will start this campaign, and your wife may go down Michigan Avenue to select any car on the street and have it charged to me.”

As far as I know, no ordinary human being has ever resisted Albert Lasker. He has commanded what he would in this world. Presidents have made him their pal. Nothing he desired has ever been forbidden him. So I yielded, as all do, to his persuasiveness. I went to Indianapolis that night.41

Shortly afterward, Lord & Thomas publicly announced that it had retained the services of Claude C. Hopkins. Lasker assembled the office staff one morning and told them about the new hire, who would be paid the astounding sum of $1,000 per week—more than twice what John Kennedy had commanded only two years earlier. “My instinct for showmanship was fully gratified,” Lasker later remembered, “when I heard a voice at the rear of the crescent-shaped clustering of our people repeating with awestruck emphasis, ‘—a week!’”42

That same morning, in conversations with groups of staff members, Hopkins began imparting his theory of copywriting. We should never brag about a client’s product, he said, or plead with consumers to buy it. Instead, we must figure out how to appeal to the consumer’s self-interest. The group we call “everybody” is actually a collection of individuals, each mainly concerned about him- or herself. “We must get down to individuals,” he stressed. “We must treat people in advertising as we treat them in person.”43

Hopkins had begun his adult life as a teacher, and he saw himself as a teacher still. But he was also a doer—and the task at hand was pushing pork and beans.

Van Camp presented some interesting challenges, including the fact that its pork and beans product was undistinguished. (At the Van Camp factory, Hopkins laid out a spread of a half-dozen rival brands with no identifying labels; no one could figure out which was Van Camp’s.) But this wasn’t the most pressing concern. As Hopkins soon discovered, something like 94 percent of housewives cooked their own pork and beans and weren’t interested in a canned alternative. So Hopkins decided that he first had to soften up that uninterested 94 percent of the potential market: “I started a campaign to argue against home baking . . . I told of the sixteen hours required to bake beans at home. I told why home baking could never make beans digestible. I pictured home-baked beans, with the crisped beans on top, the mushy beans below . . . Then I offered a free sample for comparison. The result was an enormous success.”44

![]()

Next, Hopkins set about “differentiating” Van Camp’s product from the competition:

We told of beans grown on special soils. Any good navy beans must be grown there. We told of vine-ripened tomatoes, Livingston Stone tomatoes. All our competitors used them. We told how we analyzed every lot of beans, as every canner must. We told of our steam ovens where beans are baked for hours at 245 degrees. That is regular canning practice . . . We told just the same story that any rival could have told, but all others thought the story was too commonplace.45

Hopkins then acted on an observation he happened to make on the streets of downtown Chicago. At the restaurants and lunch counters into which Hopkins poked his head, a large number of the men at the tables and counters were consuming factory-baked pork-and-bean products. This, of course, was simply semantics: by definition, commercial establishments couldn’t provide “home-cooked” meals, so diners who liked pork and beans for lunch took what they could get. But Hopkins realized that many housewives were ready to quit the onerous, sixteen-hour process of making pork and beans from scratch. He told them that their “men folks were buying baked beans downtown,” and “told them how to quit easily.”46

Soon, Van Camp was able to command a premium for its unremarkable pork and beans, and emerge as the dominant national brand.

An overlapping story begins in 1908, when the head of the American Cereal Company, Henry Parsons Crowell, got in touch with Lord & Thomas. Crowell—a devout Christian who went into business to serve God after recovering from a childhood bout with tuberculosis—had bought the run-down Quaker Mill in Ravenna, Ohio, in 1881. One of the first manufacturers to start packaging and selling oats directly to consumers, beginning with its “Pure Quaker Oats” in 1884, Crowell had created one of the nation’s most successful branded cereals. In 1901, he joined forces with three other cereal magnates to found American Cereal (henceforth “Quaker”), headquartered in Chicago.47

Over its early history, Quaker employed a variety of ad agencies.48 Quaker felt that it didn’t need Lord & Thomas’s help in selling its flagship oats; on the other hand, as Crowell informed Hopkins at a 1908 meeting, the company had a portfolio of products that were only bumping along. Impressed with Lord & Thomas’s recent string of successes, he offered to put $50,000 into promoting a Quaker product of Hopkins’s choosing.49

Hopkins soon settled upon two odd products—Puffed Rice and Wheat Berries—which had been introduced as novelties at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. They were manufactured by a similar process: Raw grains were placed in long metal cylinders that looked something like rifle barrels. Hot compressed air was then injected into these tubes, and the kernels of grain expanded to something like eight times their original size. When the cylinder was opened, the compressed air exploded out, carrying with it the “puffed” cereal.

Hopkins loved it. It was visual, counterintuitive—and patented. Quaker controlled the puffing machinery, and for the time being, at least, nobody else could make puffed cereals in just this way; this made it a far better business than corn flakes. Into Hopkins’s head popped the soon-to-be-immortal phrase: Food shot from guns.

Of course, Lord & Thomas still had to lay the groundwork for a successful campaign. Looking at the economics of cereal manufacturing and distribution, Hopkins and Lasker realized that the rice and wheat products had to be sold together to justify the cost of advertising them. This meant that Wheat Berries needed a new name: “Puffed Wheat.” Quaker agreed. Next, Lord & Thomas argued for a price increase: from 10 cents to 15 cents a box for Puffed Rice, and from 7 cents to 10 cents for Puffed Wheat. Quaker worried that this would kill sales of two products that were already in decline; Lord & Thomas argued that the price increases would pay for the advertising needed to drive up sales.50 Once again, Quaker acquiesced. The agency contacted retailers and suggested that they stock up before this price increase, which had the welcome effect of driving up sales.51

Then Hopkins went to work. He invented a personality, Professor Alexander P. Anderson—in fact, the real-life Quaker Oats technician from the University of Minnesota who had developed the puffing process—to explain the science behind puffed cereals. (“Personalities appeal,” Hopkins observed, “while soulless corporations do not.”52) He lovingly wrote up the process (125 million steam explosions in every grain!). He described the puffed grains (eight times their original size!). He hammered away at the theme of “foods shot from guns”—a theme that elicited howls of derision from the advertising community: “That idea aroused ridicule. One of the greatest food advertisers in the country wrote an article about it. He said that of all the follies evolved in food advertising this certainly was the worst. The idea of appealing to women with “Food shot from guns” was the theory of an imbecile.”53

Not so: Puffed Wheat and Puffed Rice were soon the most profitable breakfast foods on the market. Quaker, astonished, retained Lord & Thomas to promote its flagship Quaker Oats and other products.54

Hopkins later admitted that Lord & Thomas made some mistakes with Puffed Wheat and Puffed Rice. They pushed for newspaper advertising—a mass medium—for a product that the masses couldn’t afford. (The agency soon retreated to magazine ads only.) They distributed millions of samples “promiscuously,” Hopkins recalled ruefully. (“It never pays to cast samples on the doorstep,” he later concluded. “They are like waifs.”55) One series of ads offered a box of Puffed Wheat free to anybody who bought a box of Puffed Rice. (“The offer was ineffective . . . it is just as hard to sell at a half price as at a full price to people who are not converted.”56) But the agency learned from its mistakes, and when the next consumer product came through the door, Lord & Thomas was far better prepared.

Hopkins never ceased being the scheme man who had taken Grand Rapids and Chicago by storm, and at Lord & Thomas he persisted in his promotional ways. These, combined with Lasker’s powers of salesmanship, continued to generate marketing miracles.

One such scheme involved the creation of an “advisory board” in the Chicago offices of Lord & Thomas. This lofty-sounding body was actually sixteen Lord & Thomas employees, over whom Hopkins presided. Using Judicious Advertising and other vehicles, Hopkins heavily advertised the existence of this board, which was available to help anyone with an “advertising problem.”

As Hopkins wrote in a 1909 Lord & Thomas publication called Safe Advertising: “Here we decide what is possible and what is impossible, so far as men can. This advice is free. We invite you to submit your problems. Get the combined judgment of these able men on your article and its possibilities. Tell them what you desire, and let them tell you if it probably can be accomplished.”57 Several hundred entrepreneurs came to the advisory board’s table. Some 95 percent of them—those with what Hopkins called “dubious prospects”—were told to give up on advertising. The remainder, of course, were good prospects for Lord & Thomas.

Two visitors not sent packing were B. J. Johnson, head of the Milwaukee-based B.J. Johnson Soap Co., and his newly appointed sales manager, Charles Pearce, who appeared before the advisory board one morning in 1911.58 The company had been founded a half-century earlier, in 1864, and was mainly known for its Galvanic laundry soap. But even in 1911, the laundry-detergent field was a cutthroat arena, and the advisory board advised against a Galvanic campaign.

Do you have anything else, the board asked? Yes, Johnson and Pearce said, they did have another product—a bar soap made from palm and olive oils. The soap, which had been on the market since 1898 and had a nearly undetectable market share, was called Palmolive. The delegation from Milwaukee had low expectations for their obscure bar soap, but the Lord & Thomas board felt differently.

After internal discussions, they proposed to Johnson that the company mount a small test. Galvanic was then sold mainly through grocers. Lord & Thomas would approach these retailers in test markets and ask them to participate in a promotion called “Johnson Soap Week.” During Soap Week, shoppers who purchased a tin of Galvanic would be given a bar of Palmolive. Grocers who agreed to purchase Palmolive in advance would be listed in full-page advertisements telling consumers where they could get their “free” bar of soap. Johnson agreed to the scheme, and the promotion proved successful, establishing a “solid trade” in the obscure Palmolive brand.59

The real challenge, though, was to get Palmolive out from under the skirts of Galvanic and into drugstores, where it could stand on its own. The agency proposed a novel campaign in Grand Rapids for $1,000. When Johnson objected to the price, Lord & Thomas proposed a scaled-down experiment—for $700—in the lakeside town of Benton Harbor, Michigan. Johnson agreed.

The agency ran a series of ads touting the “beauty appeal” of Palmolive, and announcing that the manufacturer would “buy a cake of Palmolive for every woman who applied.” The next ad contained a coupon good for a ten-cent cake of soap at any store. The dealer, according to the coupon, would then charge Palmolive ten cents.

The notion of a dime changing hands, or at least appearing to change hands, was central to Hopkins’s scheme. (In fact, the dealer would be buying the sample bars at wholesale prices of less than a dime, thereby receiving a guaranteed profit on each bar sold.) The coupon gimmick also helped persuade dealers to stock the product. Lord & Thomas mailed a copy of the coupon in advance to local retailers, pointing out that every household in the vicinity would soon be getting one of these coupons—worth a dime, back in a day when a dime was worth something—and that consumers would certainly redeem them somewhere. The threat was clear: existing customers might go elsewhere. “We gain[ed] by this plan universal distribution immediately at a moderate cost,” Hopkins boasted.60

At a cost of approximately $700, Lord & Thomas persuaded several thousand Michigan women to try Palmolive. The product was good—the essential building block, according to both Lasker and Hopkins—and repeat sales in Benton Harbor paid for all advertising costs even before the bills came due. “We knew we had a winner,” wrote Hopkins.61

A subsequent test in Cleveland (where Palmolive sales had up to that point averaged about $3,000 per year) generated $20,000 in sales. Consumers redeemed twenty-thousand coupons, costing Johnson $2,000. With an additional $1,000 for newspaper advertising figured in, the campaign cost a total of $3,000, or about 15 percent of gross sales.62

From then on, it was simply a matter of ratcheting up the scheme in a series of ever-larger markets. When every local test returned the same results, Lord & Thomas persuaded Johnson to take Palmolive national. Buying a full page in the Saturday Evening Post, Lord & Thomas drew up an ad that made essentially the same offer that had been made in Benton Harbor. Then the agency sent out letters to fifty thousand druggists and retailers all over the country, explaining what was about to happen. More than $50,000 worth of orders poured in for a soap none of these retailers had ever seen. As an internal Lord & Thomas account put it:

It is an astonishing fact that on this circular alone, before the advertising appeared, over $50,000 worth of the soap was sold and the resultant sales in the four weeks following the appearance of the advertisement totaled almost $75,000. Almost 200,000 coupons were redeemed and the advertiser had gained a foothold on a national basis that had never before been contemplated. The astonishing thing was that the soap orders came from over 300,000 cities, towns, and hamlets in the United States and Canada.63

A juggernaut was now in motion. A similar ad four months later in the Ladies’ Home Journal generated a huge response. Dealers began placing ads—totaling some $30,000—announcing that they would redeem the Palmolive coupons. Johnson sold more than $100,000 worth of soap before the ad appeared. A year after the advertisement appeared in the Journal, Johnson was still redeeming up to two thousand coupons per month. An astonishing 99 percent of drugstores stocked Palmolive and ordered new stock on an average of between three and four times a year.64

Palmolive was now the best-selling soap in the world. One reason was that, despite the costs associated with advertising, Palmolive (at ten cents a bar) remained the lowest-priced “beauty soap” on the market. Competitors that traditionally had sold high-end soaps for as much as twenty-five cents a bar were forced to cut their prices to stay competitive.65

In 1916, B.J. Johnson Soap changed its name to the Palmolive Company.66 Lord & Thomas promoted a variety of products under the Palmolive brand—including shampoo and shaving cream—with great success, and the account remained with the agency until the 1930s.

Now comes one of the stranger stories from the Lasker-Hopkins heyday, drifting into the darker realms of commercial espionage and betrayal.

The melodrama begins in 1907, shortly after Hopkins’s arrival at Lord & Thomas. The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company—an Akron-based tire manufacturer founded in 1898 by Franklin A. Seiberling and his younger brother Charles—was an established Lord & Thomas client with a consistent annual ad volume of about $40,000. Although this was a respectable figure for the early years of the twentieth century, Lord & Thomas proposed a significant expansion of the tire manufacturer’s advertising. After prolonged debate, Goodyear agreed to increase its ad budget to $250,000. This sum was twice as much as the company’s entire profits from 1906 and represented an enormous gamble.67

The huge expansion of the Goodyear account occasioned a memorable moment at Lord & Thomas. Robert Crane, then a young copywriter, was talking with Hopkins in Hopkins’s office: “Suddenly the door opened, and in rushed Lasker. Hopkins was standing up with his back to the wall, about two or three feet away from the wall. And Lasker doubled up his fist, and hit Hopkins in the chest, and said, ‘By God, Hopkins, we landed it!’ And Hopkins bumped his head against the wall, and his eyes bulged out, and he didn’t crack a smile. And said, ‘Isn’t that gratifying?’”68

But a problem soon emerged. After visiting Akron and prowling around the Goodyear plant, Hopkins confessed that he couldn’t figure out the merits of the tire that Goodyear was then promoting: the Straight Side tire, introduced in 1906.69 Who cares if a tire has “straight sides,” he asked? Don’t all tires have more or less straight sides? Goodyear’s technicians rushed to straighten him out. This patented construction, they told him, meant that size for size, Goodyear tires had 10 percent greater air capacity. Just as important, they could not be cut by the rim of the wheel in the wake of a puncture.

Hopkins listened, pondered, and came up with a plan: “I coined the name ‘No-Rim-Cut Tires.’ Across every ad, we ran the heading, ‘No-Rim-Cut Tires, 10% Oversize.’ The results were immediate and enormous. Sales grew by leaps and bounds. Goodyear tires soon occupied the leading place in tiredom.”70

According to Lord & Thomas records, sales of the No-Rim-Cut tire doubled in four months. Goodyear’s business increased from $2 million in 1906 to $9.5 million in 1910, reflecting both effective promotion and a huge surge in car production (from 33,200 cars produced in the United States in 1906 to 181,000 in 1910).71 By 1911, the company’s Akron plant was operating twenty-four hours a day to keep up with demand.72

Competitors soon imitated the No-Rim-Cut design, so Hopkins moved on to another angle: the tire’s patented, diamond-pattern antiskid tread, first introduced in 1908. He decided that this should be called the “All-Weather” tread. Again, sales boomed. Goodyear became the nation’s leading tire maker. Ad budgets grew from $250,000 a year—a sum that Goodyear had ventured with some trepidation—to an astounding $2 million.

But all was not well between Lord & Thomas and Goodyear. “I lost it,” Hopkins later wrote of the Goodyear account. His explanation was characteristically vague: “There developed a desire for institutional advertising which I could never approve.”73

Actually, the account left the Lord & Thomas fold for several reasons, including dramatic changes then taking place within the agency. In 1912, Albert Lasker decided that he had to get rid of his sole remaining partner, Charles R. Erwin. Lasker had muscled his way into his ownership position at the agency in 1904 with Erwin’s support. Over the next eight years, however, he became frustrated with Erwin’s minimal advertising skills. Erwin was a “business-getter,” in Lasker’s estimation, but not an ad man. Hopkins, too, had little use for Erwin. “He liked Mr. Erwin tremendously,” Lasker later commented, “[but] had nothing but the most supreme contempt for him on advertising, which he realized Erwin didn’t grasp at all.”74

In 1910, Lasker opened a Lord & Thomas office in New York, at Fifth Avenue and Twenty-Eighth Street, putting added pressure on himself to build business in two cities.75 By 1912, Lasker’s irritation with Erwin came to a head, and he announced that he wanted out. “I went back to Erwin,” he later recalled, “and told him that I wanted to split partnership with him . . . that I realized that I was a lone wolf, that I couldn’t be in a partnership.”76

Erwin took the bad news graciously. He knew Lasker was the true driving force behind the business, and generously suggested that Lasker should take more than half of the agency. Lasker made a counterproposal: “No, Mr. Erwin, that is totally unfair . . . I am going to make you a proposal. I will give you $400,000 for your half interest, and you agree not to go into the advertising business. Or, I will take $200,000 for my half interest, and I will agree not to go into the advertising business.”

It was a clever formula that Lasker used several times in his life: offering to buy out the other party for a certain sum or to be bought out for half that amount. Erwin chose to be bought out and arranged to stay on at the agency for five years as a non-partner. The changes were not divulged publicly. Erwin retained his title of president and an annual salary of $18,000.

By the end of 1914, however, Lasker had had enough. “I still had to pull my punches,” as Lasker later explained it, “[so] I asked him to go.” Lasker felt that he had done right by Erwin, but later admitted that Erwin never forgave him for forcing him out of Lord & Thomas.77

Soon enough, though, Lasker had his own reasons for feeling aggrieved. Several years earlier, Erwin had hired a young man named Louis Wasey. In Lasker’s estimation, Wasey was one of the ablest recruits ever to join Lord & Thomas. One day in 1915, Wasey advised Lasker to fire a colleague named W. T. Jefferson, whom Wasey described as a “bad influence.” Lasker did so, giving Jefferson a generous severance package. About two months later, Wasey resigned from Lord & Thomas and went into business with Jefferson.

In those interim two months, however, Lord & Thomas salesmen noticed that whenever they went out in response to a prospective client’s call, they ran into representatives from “Jefferson & Wasey” pitching to that same company. Lasker’s hardnosed lawyer, Elmer Schlesinger, decided that Lord & Thomas’s switchboard operator was slipping information to the rival agency. He arranged a fake inquiry from a friendly firm, and—sure enough—Jefferson & Wasey showed up. The switchboard operator was fired and shortly thereafter turned up as Jefferson & Wasey’s switchboard operator.

At about this time, Charles Erwin also joined the new agency, which was renamed Erwin, Wasey & Jefferson.

Meanwhile, there was the problem of Goodyear. The tire company was originally Erwin’s account, but it had been built up mainly by Hopkins. When Erwin left Lord & Thomas, Goodyear stayed with Lasker’s agency, even though Goodyear cofounder Frank Seiberling felt less comfortable with Lasker than with Erwin. Seiberling’s discomfort was heightened by his increasing irritation with Hopkins, who disdained the kind of institutional advertising that Seiberling was now demanding. “Seiberling wanted to be glorified institutionally,” copywriter Mark O’Dea explained, “[and] Hopkins and Lasker wanted to tell why the tires were better.”78

All of these factors converged, and a crisis erupted one day in this tumultuous year of 1915. Seiberling called a summit conference with Lasker and demanded that Hopkins be taken off the Goodyear account. “That put me on the spot,” Lasker recalled. Lasker agreed with the client in the particulars of the case, but felt it was “one of those stubborn places” where he couldn’t influence Hopkins. And humiliating Hopkins by bumping him from the Goodyear account might lead to disaster. “I knew I’d lose [Hopkins] for everything else,” said Lasker, “and that left me no choice.”79 He refused to move Hopkins. As expected, Goodyear fired Lord & Thomas and retained Erwin, Wasey & Jefferson.

As a rule, Lasker didn’t mind when his subordinates left Lord & Thomas and went into competition with him. Later in his life, in fact, he took great pride in the fact that thirty-nine agencies had been founded by Lord & Thomas alumni. But he believed in honorable partings of the ways, and he felt that Wasey had behaved dishonorably. “He is the only man that ever I was connected with,” Lasker later commented, “that did something that was studiedly wrong.” Although Lasker rarely held grudges, he resented Wasey for the rest of his life.

Claude Hopkins earned every bit of his legend, and he was incredibly productive. “Hopkins could photograph the thing instantly,” Lasker later commented. “Three days after he would take over the thing, he would have an immortal campaign written.” In fact, Lasker sometimes sat on Hopkins’s output for days or weeks, fearing that the client wouldn’t value a product that had been generated so quickly.80

Hopkins enjoyed no forms of amusement, Lasker recalled; he worked incessantly, although, like Kennedy, he was a “prodigious drinker.”81 As Mark O’Dea wrote, he was also a hard man to fraternize with:

Hopkins was always difficult in conversations. His intimacies were few. He was far from a social being . . . never a mixer. In many ways, he was Lasker’s opposite, for the latter was cosmopolitan, gay, voluble, and won a countless host of friends from Presidents to caddies. Whereas Lasker was versatile, Hopkins was single-traced. His one subject was advertising copy. For music, books, politics, sports, plays, personalities, he had little concern.82

Although in later years he preferred to work out of his house in Spring Lake—only coming into Chicago every ten days or so—Hopkins exerted a huge impact on the firm. His presence and his success changed the status and stature of copywriters at Lord & Thomas. Before Hopkins’s arrival, copywriters proposed, but the solicitors—the salesmen on the street—disposed. Under Hopkins, the copywriters became kings.

He also worked effectively with Lasker in a process they called “staging.” A solicitor would get a foot in the door and speak glowingly of “Mr. Lasker,” the magical, driving force behind the Lord & Thomas phenomenon. Then Lasker would take the next round with the prospective client, living up to his own advance billing and all the while singing the praises of the astounding “Mr. Hopkins.” By the time the client met the master himself—the Merlin of Lord & Thomas—the effect could be intoxicating.

After the account was landed, Lasker and Hopkins continued to work the client. Lasker recalled how he and Hopkins played their own version of good cop/bad cop:

I always said [to Hopkins]: “We will divide up this way . . . Whenever I find you are going to differ with them, I am going to agree with them, not to be the diplomat, but so we can explore the difference . . . You stand for our viewpoint, Mr. Hopkins, and I will get on his side. As it develops, I will make up my mind . . . If I think he is right, I will argue it up with you, and I will have no trouble convincing you. If I finally think he is wrong, I will turn to him and say, ‘Mr. Blank, I guess we are both wrong.’”83

And what of Lasker’s own role? Even more than in the Kennedy era, Lasker was the extraordinary manager of an extraordinary talent. He grasped Hopkins’s unique gift for identifying the Big Idea and nurtured that gift. He went in ahead of Hopkins, and—as in the case of Goodyear—also stood behind him.

At the same time, he was quick to point out that Lord & Thomas had even greater successes after Hopkins left the company in the 1920s. He was offended by Hopkins’s account of his years at Lord & Thomas—in a book that he claimed, implausibly, he never read—because he felt that Hopkins had slighted him in it: “He mentioned me casually, just like ships that pass in the night . . . [but in] all that period of Lord & Thomas where he says he did it, it was Hopkins and myself. No doubt that he created all the creative part. [But] there is also no doubt . . . that I did the selecting, and told him what to develop . . . and what not to develop in the creative end.”84

“Creating all the creative part” was an indispensable factor in Lord & Thomas’s success, and Lasker compensated Hopkins accordingly. Although Hopkins’s stated starting salary was a staggering $52,000 a year—a figure that Lasker trumpeted far and wide—Hopkins in many years made at least three times that amount, counting bonuses. In fact, Lasker had to steer accounts away from his prodigious copywriter so that there would be work and bonuses for others in the shop.

Despite their falling-out in the 1920s, Lasker always gave Hopkins full credit for his enormous contributions to Lord & Thomas. “I never knew a finer, more earnest man than Mr. Hopkins. No greater advertising man lived or ever will live.”85

Arguably, Lasker could have claimed that distinction for himself. But of the several master copywriters whom the master of Lord & Thomas discovered and nurtured, Hopkins was far and away the most versatile, productive, and durable.