Chapter Two

![]()

The Galveston Hothouse

![]()

IN LATE APRIL 1892, the Galveston Free Press heartily endorsed the candidacy of George Clark—an attorney from Waco with extremely close ties to the railroads—for governor of Texas.

Clark was running for the Democratic nomination against incumbent James Stephen Hogg. A notable milestone of Hogg’s first term had been the creation of the Texas Railroad Commission—a powerful body modeled on the Interstate Commerce Commission that administered the state’s railroad-related laws. The legislation that created the Railroad Commission allowed the governor to appoint its three members. Clark ran against the Commission as a “constitutional monstrosity,” and called for the popular election of Commissioners.1

Citing Clark’s progressive and tolerant spirit, the editorial writer enjoined Texans to support him:

The office of the governor already has enough power without being given that of the appointment of three railroad commissioners who are invested with authority to make and unmake the greatest corporations in the state. Such power held in the hands of the governor invites suspicion, favoritism, and, worst of all, corruption . . . Judge Clark will add a spirit of tolerance and progressiveness foreign to the nature of the present executive. By all means let Judge Clark head the ticket and Texas will experience a change that will be “what she has sought and mourned because she found it not.”2

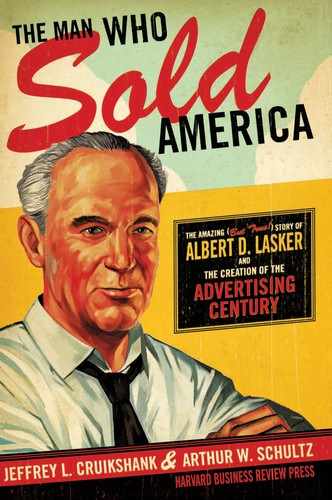

The editorial was remarkable not so much for its arguments—although they were cogent and sensible enough—but for the fact that its author, Albert D. Lasker, was still nine years away from being old enough to vote. On the day that these opinions appeared in print, Albert Lasker—writer, editor, and owner of the Galveston Free Press—was a day short of his twelfth birthday.

The Free Press, which Lasker published for more than a year, was a four-page weekly that commanded a yearly subscription price of $1. In addition to editorials, the newspaper ran theater reviews, social notes, and other local news. It also contained advertisements for local businesses, all written and laid out by Lasker. The only aspect of newspapering that Lasker did not undertake personally was the collection of payments from subscribers and advertisers. This, Lasker felt, was beneath his dignity. To dun deadbeats, Lasker hired a boy even younger than he was.

The formula worked. From the operations of the Galveston Free Press, Lasker netted around $15 a week, at a time when $60 a month was a respectable salary for an adult in Galveston.

Albert Lasker was one of six children. He had an older brother, Edward, a younger brother, Harry (his mother’s favorite, whom Albert loved to torment), and three younger sisters—Florina, Etta, and Loula.

The Galveston of Lasker’s childhood was a lively, sociable, and relatively liberal Southern port. The city’s most fashionable residences faced the Gulf. The Lasker house was almost at the geographic center of the Galveston peninsula, although several blocks from the water. It was a stately red Victorian on the corner of Broadway and 18th Street that Lasker’s first biographer described as “a castle—or prison—out of Grimm . . . a crenelated, gabled house . . . built of bright red sandstone, with sturdy masonry, a white window trim, round copings . . . iron balconies, Corinthian columns, triangular porches, and ornate glass bulges set at improbable angles.”3 It sat atop a small hill, and was usually surrounded by well-tended flowers.4

The opulent façade bespoke the very comfortable lifestyle within. Lasker recalled a childhood home in which there were “always lots of servants, and lots of maids, and a butler.”5 Albert’s sister Loula was somewhat more precise: there were three servants and a full-time gardener, of whom the maid was white, and the other three staffers were African American.6

Nettie Lasker, although the junior partner in her marriage, was nevertheless a commanding presence. “I used to think when I was a girl that she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen,” recalled one of Lasker’s schoolmates. “She had that cameo loveliness, that expression. Deep brown eyes, and a beautiful figure, and was very stylish.”7 On Saturday mornings, the family walked to the local synagogue in their best outfits, herded along by Nettie. Mortified by her husband’s lack of attention to his dress, Nettie compensated by making sure that the rest of the family was immaculately turned out.

Through the florid hand of a ghostwriter in the 1930s, Lasker later recalled these outings as among the worst memories from his childhood. As they paraded down the street in their Saturday finery, they drew jeers and taunts—including the racial insult of “sheenie”—from their schoolmates:

We wore Eton collars; sensitive, quiet Edward, three years my senior, had a watch in his breast pocket, and the chain of gold which advertised this fact seemed to me a kind of badge he wore as my father’s first born. Our flaring bow ties were silken plaids. Truculent, round-headed Harry, who had come into the world two years after me, had his arms immersed in hand-made lace to the elbows of his jacket, although not of his free will. The vamps of his shoes were of patent leather; the rest of the uppers were the natural shade of kid. My suit had tight little pants that ended gracelessly at the knees. On our heads we wore bowler hats, an indictable offense in the sight of other boys, I guess, but the high crime was what we carried in our hands, silver mounted walking sticks. We would have been better off with baseball bats . . .8

On every day but Saturday, the Lasker children mixed easily with the youth of Galveston, but Lasker later said that this weekly encounter with intolerance taught him to “live without having intolerance to any human being in the world.”9

![]()

Albert’s childhood was rife with contradictions both subtle and pronounced. In the local business community, his father’s status commanded respect, but the family’s religion kept them at the margins of society. Life at home also carried contradictions; while the family was well off financially, at least in the early years of Lasker’s’s life, the children were not always happy. John Gunther, Lasker’s friend and biographer, condemned Morris as a “complete tyrant, a dictator,” and claimed that neither Morris nor Nettie ever gave Albert the unconditional love that he craved.10 Through his early adulthood, Albert struggled to live up to his father’s expectations. As a child, though, he feared his father, and lied to him to avoid confrontations.

Morris first beat Albert when he was about nine. The boy was spending all his afternoons at the building site for his family’s new home—the grand manse on Broadway and 18th.11 Albert would fetch and carry when he could, and talk with the workmen. One summer afternoon, when the crew had completed the framing-in of the roof, they took Albert aside and explained solemnly that it was a Texas tradition that the builders be treated to a barrel of beer when they reached this milestone. Albert rushed home to convey this news to his father, who immediately arranged to have a keg delivered to the construction site. When Albert reappeared there shortly thereafter, he was greeted as a hero. As the workmen gathered around the keg, one of them handed Albert a mug, and told him to help himself. An hour later, thoroughly drunk, the boy stumbled home. Even through his first-ever alcoholic haze, he resolved that he would not breathe a word to his mother about what had happened.

But Nettie saw immediately that something was wrong with her slurring and staggering little boy. In a panic, she summoned their next-door neighbor, a physician. Albert later recalled what happened next:

I can hear my mother frantically telling the doctor that I must have had sunstroke or something had gone wrong with the brain. The old doctor came over to me, smelled my breath, and said, “Has anyone given this child liquor?” And then my mother remembered the [keg] of beer, and my father came home and he gave me a tremendous licking, and he made me do something that he never did . . . before, or after. He made me eat for a whole day in the kitchen where the negro servants ate.12

The punishment rankled. Even at that tender age, Albert had a keen sense of justice, and he felt that his severe “licking” and subsequent humiliation were unfair.

Thus began a cycle of pranks, lies, and punishments that came to define Lasker’s relationship with his father. When the Galveston Free Press got into financial trouble—apparently, its twelve-year-old publisher incurred a printing bill he couldn’t pay—he led the printer to believe that his father would cover all of his obligations. When asked by Morris if he had made such a representation to the printer, Albert lied. The truth came out, and Albert got another “licking” in the attic.

The family’s privileged lifestyle was threatened, quite suddenly, by the Panic of 1893. Across the country, entrepreneurs were crushed by the economic upheaval, so Morris’s story is unusual only in its details. He had decided to go into real estate, founding the Lasker Real Estate Company in 1880. Seeing great potential in central Texas and the Panhandle, he went to London in 1888 to solicit partners in an ambitious development venture. A London banker bought Morris’s pitch, and loaned him $250,000: a huge sum, which he invested in San Angelo—a brand-new town some four hundred miles northwest of Galveston—as well as in a Houston subdivision.13

Then disaster struck. The mighty Reading Railroad failed, sparking a collapse of other railroads and banks across the United States. The panic quickly spread across the Atlantic, hitting banks in London especially hard. Texas’s all-important cotton crop became almost worthless as mills in England and the United States locked their doors. All across cotton country, land values collapsed.

By this time, Morris had interests in flour mills and other commercial properties throughout Texas, and he had placed mortgages on all of these properties to pay for his development projects. He was severely overleveraged, and cash was short. Rather than force his family to live in reduced circumstances, Morris sent his wife and younger children to Germany for a year. By this time, Morris’s oldest son, Edward, was away at school in North Carolina, so only Albert remained at home in Galveston with his father.

It was a bad arrangement, with surreal consequences for Albert. While he slept, or pretended to sleep, his father would stealthily enter his bedroom and pace. Albert recalled: “I would see a wraith-like, nightgowned figure. It would be my father, sleepless from worry . . . Sometimes for hours I would be aware of the pat, pat, pat of his bare feet pacing the room. Sometimes I would become wide-awake from more disturbing sounds. Behind him he would smack the palm of one hand against the hairy back of the other, then re-clench them, and groan.”

If Albert gave any hint that he was awake, his father would launch into an obsessive rehashing of the chain of disasters that had led to this nightmare: “If I sat up, he would talk to me. He was a lion at bay, bewildered by misfortunes that threatened to be overwhelming. What caused him anguish was no ordinary fear of losing money. All his dreams, all his midnight terrors, were caused by the prospect of being unable to meet his business obligations. To him, a debt you could not pay was in a class with murder.”14

Albert was both terrified and fascinated. He hungered for more attention from his father, “for some little show of his appreciation of what stirred inside of me.” Now he found himself in the role of confidante and wished he could escape it. On the rare occasions that Morris was able to sleep, he was beset by dark dreams. During the night, Albert could hear his sleeping father’s fingernails raking through the rug next to his bed. Within a few months, Morris had clawed his way through the rug’s thick fibers and laid bare a patch of flooring.

Was this simply the anguish of a merchant facing ruin, or was Morris suffering through the kind of affective disorder that had plagued his brother, and soon would afflict his son? Some of Morris’s symptoms—the insomnia, the obsessiveness, the intermittent inability to take action, the inclination to simplify his life through a self-imposed solitude—hint at the kind of emotional distress that has surfaced across the Lasker generations.

Gradually, Morris turned his business affairs around and regained his financial and emotional footing, thanks largely to the general economic recovery. For Albert, however, the memory of those sleepless Gulf nights never fully receded: “I received the full impact of the panic as a lesson. Throughout my business life, I never borrowed; I never asked a living soul to lend to me on the premise that I perceived some way of making money.”15

At the same time, Morris’s travails had a nearer-term impact: they made Albert all the more impatient to make his own way in life.

In 1892, Albert Lasker entered high school. Ball High School, founded in 1884 through a $50,000 bequest from Galveston businessman George Ball, was the first public high school in Texas. It was an impressive structure, with a central domed core flanked by two Italianate wings. The course of study was even more impressive for that time: English, history, algebra, arithmetic, economics, geography, Latin, civil government, trigonometry, physics, political economy, chemistry, philosophy, and physiology.16

Lasker, however, was too restless to do well in high school. “School is too slow for a mind like that,” his childhood friend Ann Austin later observed.17 Lasker recalled that he was “bored to death” by the teachers and found most of his classwork either irrelevant or too easy to take seriously.18 He took the economics course during his second year; it was taught by the grammar teacher, a “lovely old lady” who had been teaching in the Galveston schools for a quarter of a century. Her ignorance of economics was “colossal,” recalled Lasker—who found that he had a natural bent for the subject—and he soon knew more about the dismal science than she did. After the first class, he took his textbook home and read it from cover to cover in one night, quickly absorbing all the main lessons.

In other subjects, such as Latin, Lasker proved a far less gifted student. He became (as he later recalled) “weaker and weaker” in school. He developed an addiction to dime novels. He passed his classes only with the help of “ponies”—contraband copies of tests that were passed from student to student—or through the application of his relentless charm.

Although neither an athlete nor a stellar student, Lasker exhibited a drive and appeal that won others over to his causes—and he almost always had a cause to promote. For example, with the encouragement of his principal, Lasker organized and edited the B.H.S. Reporter, a school magazine that was first published in April 1893. The magazine, recalled a childhood friend, required advertising support from downtown merchants, and the hunt for ads earned Lasker special privileges: “The one picture that stands out today [is that] after we got the little magazine started, [Albert was] darting out first thing in the morning after these ads, with this great bundle of stuff under his arms . . . And we all envied him because he was allowed to run the streets while we had to study.”19

Because he was younger and smaller than most of the children he went to school with, he needed to have people meet him on his own terms. “Some of the boys were more than twice my size,” he later commented. “Consequently, playing with them meant that I got knocked about and they had the fun. I did not like the percentage.” He had to live by his wits, pick his battles, and be assertive. This did not always come easily to him. “My forwardness,” he concluded later, “came from the fact that I have been shy all my life.”

“With me,” Lasker once wrote, “everything always had to be dramatic. I don’t mean that it had to be . . . distorted, but all my life I have believ[ed] there is drama in everything and that the fun of life, or the fullness of life, is to find where that drama is.”20 When he told a story, he wanted that story to be spellbinding. It was not enough that it be funny; it had to be hilarious. It couldn’t be merely interesting, but thrilling. It couldn’t be just touching; it had to be deeply moving. Little stories got bigger and gained momentum.

It’s not surprising, then, that his stories of his Galveston childhood became more and more colorful over the years. One such story involved the legendary African American fighter, Jack Johnson, who was born two years before Lasker and grew up in Galveston. From the vantage point of more than a century later, it’s unclear how, or even if, Lasker knew Johnson. One story suggests that Johnson’s mother, Tina, took in washing for the Laskers.21 Another asserts that Johnson worked as a custodian for the Galveston Athletic Club, of which Lasker supposedly served as secretary.

As Lasker told the story in later years, he had arranged for an out-of-town heavyweight to come to Galveston and fight a local favorite as a fundraiser for the club. The club’s boosters, including Lasker, sold out the house for the night of the fight, only to discover that their local hero had panicked at the sight of the formidable out-of-towner and skipped town. Lasker said he persuaded Johnson to put down his broom and put on a pair of gloves, step into the ring—for the first time in his life—and go several rounds with the champ.22

Other accounts are more detailed, and more obviously inaccurate. One has Lasker inviting veteran boxer Joe Choynski to town to fight a local pugilist whom Lasker had backed with his own money. Supposedly, Lasker persuaded Johnson—who in this version of the story had worked for Lasker’s uncle—to go four rounds with Choynski, thereby saving Lasker’s investment and launching his own boxing career.23

There isn’t much truth in any of these stories. According to Johnson’s biographer, the future world champion did work in a gym and did fight Joe Choynski—in 1901, three years after Lasker had left Galveston for good. Johnson carved out his early boxing career with little or no help from Lasker—or anyone else, for that matter. He fought a tough, 235-pound out-of-towner named Bob Thompson in the summer of 1895—when Lasker was fifteen—making it through four rounds, but he did so in response to Thompson’s open challenge: $25 to anyone who can go four founds with me.24

Lasker served as editor of his school magazine for only a semester or so before handing it off to another classmate. By that time, he had set his sights on a bigger prize—the Galveston Daily News, the region’s primary newspaper—to which he found himself inexorably drawn:

I have forgotten what excuse I had for my first invasion of the editorial department of the Galveston News; perhaps I went there to seek advice about my own small paper, possibly I carried there an announcement of some high school activity for which I was responsible. But I shall never forget my sensitive alertness, my admiration for everything in that elongated room. If only I might justify my continued presence there, I felt that I’d have nothing more to ask in life . . . I yielded every day to my desire to mount the iron staircase into that Heaven. I would sneak up there and then hang around for hours, as wistful, as eager as a stray dog.25

One night, Lasker saw his chance to break into heaven. The city editor, G. Herbert Brown, was a grumpy character who tolerated Lasker because he was flattered by the boy’s unqualified admiration. On the night in question, Brown complained that he had to review a play, and this would prevent him from going to a party. Lasker jumped at the opening, suggesting that he cover the play in Brown’s stead. Brown agreed, and Lasker’s career as a theater critic began that night.

From there, he gradually built up his responsibilities at the paper—first covering all local theatrical events, then reporting on the local baseball team, and then collecting testimonials for patent medicines produced by the Peruna Company. Peruna wanted testimonials from people “in all walks of life” in Galveston, and was willing to pay $5 for each.26 This was grand money for a high school student, and it was money that Lasker now badly needed. Hanging around with older reporters, Lasker had found that he was expected to “stand treat” at the local bars for his senior colleagues.

After barely graduating from high school in 1896, Albert went to work for his father.27 He quickly improvised a kind of shorthand that allowed him to serve as Morris’s private secretary. He also picked up some rudimentary accounting skills and got a feel for how money flowed in and out of his father’s complex enterprises. But his heart remained in newspapering. At the end of the workday at his father’s office, he would escape to the offices of the News, picking up stray assignments. He boasted that he was the “third reporter” at the News, neglecting to say that the paper only had three reporters.

Lasker’s first scoop—a story that, as he told it, cemented his position with the News and seemed an augury of a brilliant reporting career—came about through serendipity. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Fireman, a national union, was holding its biennial convention in Galveston in September 1896. Early in the conference, statements were made that impugned the honesty of union leader Eugene V. Debs. Debs—for twelve years the secretary and treasurer of the Brotherhood—had broken with the union in 1892, and gone on to found the American Railway Union. He became well known on the national stage when he was imprisoned for six months for his part in the railroad strikes of 1894.28 When an Associated Press dispatch detailing the allegations against Debs reached him at his home in Indiana, he immediately set out for the convention to clear his name, arriving in Galveston on Friday evening, September 18, 1896.29

The two leading Galveston newspapers, the News and the Tribune, resolved to scoop each other by landing a first-person interview with Debs—but Debs wasn’t talking. Because he considered his differences with the Brotherhood a private matter, he dodged the press.

As Lasker liked to tell the story, he discovered that Debs was staying at a boardinghouse only three blocks from the Lasker mansion, and just across the street from the synagogue that the Laskers attended. He says he went to the Western Union telegraph office and badgered a friend there into loaning him a messenger’s coat and hat.30 Then he headed down the street to the boardinghouse. Not daring to wear the borrowed uniform in broad daylight, Lasker hid in the synagogue until dusk. Then he donned the hat and coat, ran across the street, and began ringing the bell vigorously.

A man finally answered, and asked Lasker his business. “I have a telegram for delivery to Mr. Eugene V. Debs,” Lasker shouted.31

“Give it to me,” the man replied, blocking the doorway, “and I’ll give you a receipt.”

But Lasker kept insisting that his instructions were to give it only to Mr. Eugene V. Debs himself. As Lasker had hoped, Debs himself finally appeared in the hallway and accepted the telegram. Debs opened it, and read:

I am not a messenger boy. I am a young newspaper reporter. You have to give a first interview to somebody. Why don’t you give it to me? It will start me on my career.—Albert Lasker.32

Debs chuckled, invited Lasker inside, and made a short statement on the spot. It was front-page news, Lasker later said, adding that he made hundreds of dollars as his story was picked up by newspapers around the country. He said the New York Sun even offered him a job on the basis of on this journalistic coup.

What really happened?

Assuming that the nonbylined article printed on page 8 of the Sunday paper was by Lasker, the sixteen-year-old stringer (in the story, “The News man”) knocked on the door of the rooming house in midafternoon and asked to see Debs. A young African American woman, a servant at the house, claimed to know nothing about anyone named Debs. Lasker then circled the building several times “without making any discoveries.” He befriended two delegates to the convention, who stayed to talk with him. About half an hour later, the owner of the rooming house arrived, and Lasker asked him to take his card in to Debs. A few minutes later, the owner reemerged and invited Lasker and his two new acquaintances in to meet with the “great leader”:

They were ushered into a small room opening upon the front gallery. It was twilight, the shutters were closed, and the interior had a very uncertain and ghostly appearance . . .

From what the reporter could discern in the darkness Mr. Debs is a man about six feet tall, holds himself erect and is well knit. He is clean shaven and bald headed. He was attired in light brown garments. His face, from his full forehead down, is full of intelligence, but throughout the interview Mr. Debs seemed ill at ease and kept his lips parted in a nervous smile the whole while.

The labor leader declined to say why he had come to town but pointed out that he had attended all but one or two of the firemen’s past conventions. His business in Galveston was purely of a “personal nature,” and his conversations with the firemen’s union, if any, would be kept private.

“This ended the interview,” Lasker wrote, “and the reporter was ushered out.”

One more anecdote, also involving journalism of a sort: as Lasker told the story, he had the job of reviewing the opening-night performance of James A. Herne’s Shore Acres at the Galveston Opera House. He had already seen the play several times, and tonight he had better places to be: on a date with a young woman in Houston. So Lasker wrote up his review before he left, arranged to have it dropped off at the newspaper offices at the appropriate time, and was on his way to Houston well before the curtain went up on Shore Acres. The review was printed the next morning.

Lasker claimed the deception would have gone off without a hitch except for one small detail: just before the curtain rose on Shore Acres (as Lasker told the story) the Opera House burned to the ground. Lasker said he didn’t even bother to go back to the News to pick up his paycheck. Instead, he skipped town—heading first to New Orleans, and then to Dallas, to pursue a career in newspapers.

There are two problems with this account. “As a matter of fact,” Lasker’s biographer wrote, “this experience, or experiences closely similar to it, are a legend in the newspaper business.”33 But it didn’t happen to Lasker. There was no Galveston theater fire in the 1890s. The Tremont Theatre—long Galveston’s preeminent venue—closed in 1895, a year after the opulent Grand Opera House opened on Postoffice Street.34 The Grand is still in business today. James Hernes’s Shore Acres was performed, without incident, at the Grand on February 11 and 12, 1894.35

It is also impossible to conceive of Morris Lasker letting his son escape to degenerate New Orleans.

Lasker did have one professional interlude during his Galveston years that was both satisfying and portentous. In 1896, at the age of sixteen, he worked on Republican Robert B. Hawley’s congressional campaign.

Hawley, whom Lasker described as “the handsomest man I ever saw in my life,” was a wealthy Galveston sugar manufacturer and a close friend of Morris Lasker.36 From a political standpoint, the two made an unlikely pair: Hawley the ardent Republican and Morris the lifelong Democrat; Hawley a protectionist and Morris a proponent of free trade. But in the public debate over the gold standard—a divisive issue in the election of 1896—the two men found common ground. Morris voted for Hawley—the first and last Republican he ever supported.

Early in the campaign, Hawley approached G. Herbert Brown at the News and asked if the city desk editor would recommend someone who could travel with him and report on his speeches. Brown suggested Albert, and Morris (somewhat surprisingly) agreed to the proposition. At least once a week, Hawley would hit the road for the outer reaches of the district, and Albert would go with him, reporting on the impromptu talks that Hawley gave in the back country, mostly in rural grocery stores.

Hawley evidently had a unique appeal: he was the first Republican elected to Congress from Texas, and he would remain the only Texas Republican elected to Congress for another quarter century. As a consequence of traveling with Hawley, Albert joined the Republican Party, of which he would remain a member until late in his life.

When Hawley won the election, he offered Albert a job in Washington. Morris refused to let him go, feeling that his son was too young to accept a position so far from home. Albert had to return to his dreary life in his father’s office. For Albert, it was like going back to jail. He wrote letters, did office chores, and ran errands, all of which he considered “degrading.”

If it were up to him, of course, he would have continued his forays into the world of journalism. “Every urge in me,” he recalled decades later, “was to be a reporter.”37 But Morris strongly disapproved of journalists and journalism, convinced that they would lead Albert into a life of drunkenness and debauchery.38 There was ample evidence close at hand to support his contention: several of the reporters in Galveston had started their careers in prestigious posts such as New York City, and had gradually drunk their way down. “They drifted into smaller and smaller towns as they became more derelict,” one of Lasker’s close friends observed, “and about the last place these brilliant men got was Galveston.”39

In desperation, Albert—barely eighteen years old—announced in the spring of 1898 that he was going to enlist in the Army to fight in the war that had just broken out with Spain. Morris seems to have ridiculed the notion. Albert soon gave up on the idea of enlisting, but remained determined to escape from his father, from his office, from Galveston. He found himself in increasingly open rebellion against a powerful authority figure, and he wanted to prove himself somewhere where he wouldn’t be in Morris’s shadow.

Morris finally came up with a solution that was acceptable to them both. Years earlier, he had been instrumental in helping a Chicago advertising agency, Lord & Thomas, out of a difficult situation involving a major local debt to the agency. Daniel Lord, who had traveled to Galveston to protect his agency’s interests, was both relieved and grateful. He promised Lasker that if he could ever return the favor, he would.

Now, full of concern about his son’s future and determined to keep him out of the newspaper business, Morris remembered that promise. He had only a vague understanding of what the advertising business was, but he guessed that it had to be better than journalism. He bargained hard with his son: “You go and try that,” he insisted, “and if that doesn’t work, I’ll give you my blessing to go into reporting.”40

Out of devotion to his father, Albert agreed. “He didn’t know,” he would later say, “what a hurt it was to me.” From hanging out with the hard-drinking crew in the newsroom, Albert had learned to despise the business side of the shop. “To ask a reporter to become an advertising man was as if a father had asked a daughter to enter a life of shame! I thought, ‘My father doesn’t know what he’s asking of me, but I’ll do this. I’ll go for a few weeks.’”41

Lord & Thomas agreed to give Albert a three-month trial, at a starting salary of $10 a week. Albert quickly agreed to these terms, secretly pleased at the three-month limit.

In the spring of 1898, he boarded the train for Chicago with but one goal: do his time, satisfy his father, and then be turned free, with his father’s blessing, to pursue his real passion—journalism—in New York.