FOUR

Empirical Results

In this section we analyze the proposed relationships between the model variables. For this step, all variables were aggregated by using the ratings of four responding project participants, that is, three project team members and the project sponsor. Due to the risk of response bias, the responses of the project managers were excluded. These responses were used to fill in for missing values. The data aggregation led in a total of 114 projects. All further analyses are based on the aggregated data of the responses of the different respondents for 114 projects.

Component-related Descriptive Results

In the methods section we analyzed the quality of the measurement scales of the different model components. We showed that the PVM of a project manager could be measured with six different components. In this section we analyze the specific characteristics of the components and their relationships.

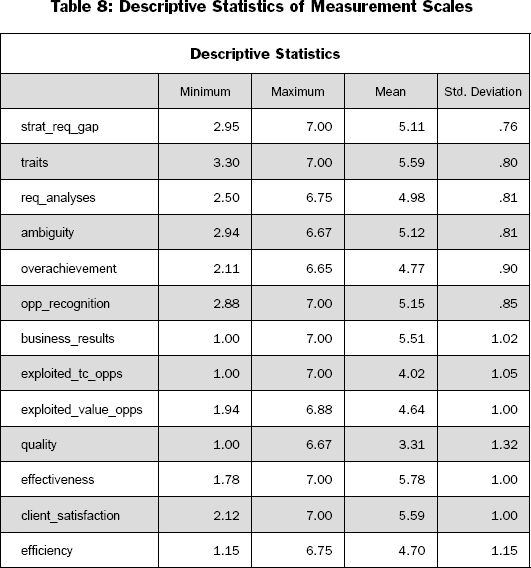

The descriptive statistics of the scales show that the means are high across all developed scales. This is not very surprising, as most reported projects were classified by the respondents as successful. Even though the minimal values are in some cases 1.0 and do not exceed 3.3. The means of the PVM scales are relatively high. But the low minimums show that in some cases project managers were not perceived to have exhibited a PVM.

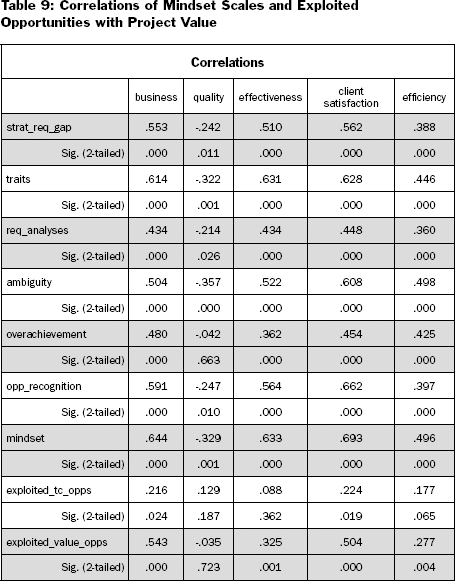

All correlations between the mindset scales and the project value scales are significant and very strong. This is a first indication of support for our research hypotheses.

Empirical Tests of Hypotheses

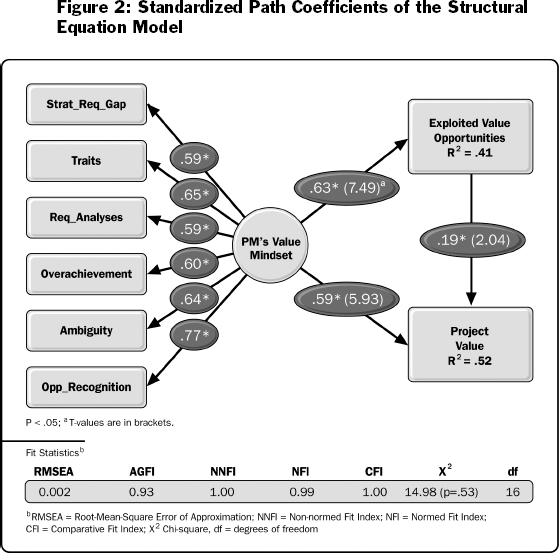

The developed measurement scales are the bases to test our research hypotheses. In the final step of our statistical analyses we simultaneously tested our three hypotheses with a Structural Equation Model (SEM) by using LISREL 8.51 for the model estimation. The SEM shown in Figure 2 displays the structural model as well as the measurement model of the project manager's Project Value Mindset, consisting of the six scales. The error terms are not shown.

The evaluation of a structural equation model is quite complex since no single test offers sufficient evidence to accept or reject a model. Recognizing the problems associated with the evaluation of linear structural equation models (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Bagozzi, 1980; Baumgartner & Homburg, 1996; Bollen, 1989; Soni, Lilien & Wilson, 1993), a comprehensive set of tests was employed to assess the goodness of fit. To accept the model, the following criteria have to be satisfied: a chi-square (p>0.05), which tests the null hypothesis that the estimated variance-covariance matrix deviates from the sample variance-covariance matrix only because of sampling errors. The chi-square test is limited to the extent that it is dependent on the sample size. Browne and Cudeck (1993) showed that with an increase of the sample size any model could be rejected. Because of these weaknesses of the Chi-square test, Jöreskog and Sörbom suggested two global fit indices, GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) and AGFI (Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index). To evaluate a model's fit we use the AGFI, since its calculation is based on the GFI but it also accounts for the degrees of freedom. Values below 0.90 indicate that the model should be rejected (Baumgartner & Homburg, 1996). The RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) is a measurement of non-centrality and estimates how well the fitted model approximates the population covariance matrix per degree of freedom. Browne and Cudeck (1993) suggest that an RMSEA <= 0.05 indicates a close fit and the model should be accepted. The CFI (comparative fit index) assesses the relative reduction in lack of fit as estimated by the chi-square of a target model versus a baseline model in which all of the observed variables are uncorrelated (Bentler, 1990). Models with a CFI below the 0.85 should be rejected (see Bentler and Bonett, 1980).

The table of the fit statistics demonstrates that the estimated model fulfills all requested statistical benchmarks and also demonstrates an acceptable fit. All path coefficients are significant (p<.05), suggesting that all model variables have to be included in the Structural Equation Model. Furthermore, the PVM variable explains 41% of the variance of the exploited value opportunities during a project's implementation. Both the PVM variable and the Exploited Opportunity variable explain 52% of the variance in the Project Value variable. This percentage is very high, given the many other possible influences on the achievement of project success.

The SEM also supports the proposed measurement model for a project manager's mindset. The path coefficients between the latent variable (project manager's value mindset) and the six different measurement scales are very high and significant on the 1% level (p<0.01). In sum, the SEM demonstrates that our three hypotheses should not be rejected; that is, we could empirically demonstrate links between the project manager's value mindset, the exploited opportunities during a project's implementation, and the perceived project value.

Discussion of Empirical Results

Overall, the empirical results of this study are surprising. The initial expectation was that many project managers follow the dominant TC-paradigm and try to create project value within the predefined constraints of their projects. Instead, the high results demonstrate that it is more common than not that project managers strive to maximize project value in seeking opportunities to improve the value proposition of their projects. The statistical results support the main propositions that project managers with a PVM seeking to maximize the value of a project achieve better project results. Given all other possible influences on project value, as mainly discussed by the cited success factor studies, the mindset of a project manager turns out to be an important contributor in achieving project success.

The empirical results demonstrate that the PVM could be measured with several different scales. Conceptually the PVM is defined by five different dispositions a project manager shows consistently over the implementation of a project. The measurement model of the PVM consists of six different scales measuring a project manager's traits, attitudes, and behaviors. The empirical results, as demonstrated by the factor analysis and the SEM, clearly indicate that all six scales are important to completely measure a project manager's PVM. This means that project managers who are perceived by team members and peers as having a PVM receive high scores on all six scales simultaneously. It is possible that individual project managers could receive a high score on a specific scale but lower scores on other scales. In these cases project managers demonstrate some aspects of the value mindset, but in summary they do not demonstrate a PVM as a whole, meaning the whole is more than the sum of its parts. All six facets of a PVM are specific and could be interpreted in the following ways?:

Overachieving Disposition—It is represented by the scale “Overachievement.” In contrast to the premise, suggesting a satisficing management approach within the TC-paradigm, the scale “Overachievement” captures perceptions of a project manager's behaviors to consistently seek to exceed the initial expectations and specifications. Successful project managers are trying to perform beyond the predefined triple constraints.

Opportunity Disposition—It is represented by the scale “Opp_Recognition.” This facet of the PVM is related to the second premise, that the TC-paradigm is not suited for managing uncertainty effectively. As discussed above, uncertainty is a necessary precondition for the occurrence of opportunities. The importance of this attitude for the PVM concept is very high, as indicated by the highest values in the factor analysis and SEM. The scale mean is surprisingly high, indicating that project managers are seeking opportunities to improve the value proposition of a project beyond the initially defined project goals. This is achieved by the behavior of looking for ways to improve the project value, as well as by the willingness to ask others for ways to exceed the expected project outcomes.

Dialectic Requirement Disposition—Another facet of the PVM construct is the willingness of a project manager to question the initial requirements and specs to improve the value proposition of a project. Thus, two scales were developed to represent two different aspects of a project's definition. The constant questioning of requirements and specifications is related to the premise of value maximization in the PV-paradigm. These attitudes are also indirectly supporting the notion of opportunity search and exploitation. The scale strat_req_gap measures a project manager's attitude of putting more effort into the requirement analysis of a project by matching the needs of the stakeholders with the technical requirements. This scale achieves the lowest variance and a relatively high mean, meaning that in practice many project managers tend to execute these tasks independent of questioning the TC-paradigm. The results for the scale requirement_analyses, measuring the attitude toward the analysis and the adjustment of the technical specifications, are surprising, as the scale achieves a slightly higher variance and a lower mean than the scale strat_req_gap. The differences between the two scales are not significant but somewhat interesting, as one would have expected the opposite results assuming that project managers are prioritizing operational issues over strategic considerations.

Ambiguity Disposition—The attitude toward ambiguity is essential for the management of projects to overcome and manage uncertainty. In particular, at the beginning of a project many issues are vague and decisions have to be made without a necessary level of certainty. The results demonstrate that project managers who accept uncertainties as part of their decisions to improve the value proposition of a project achieve better results. From this perspective the disposition for ambiguity addresses the uncertainty and the maximization premise of the PV-paradigm. This is supported by the high path coefficient and a high factor loading of the Ambiguity scale as a measure of a project manager's PVM.

Traits—A project manager's traits are an integral part of the PVM concept. In particular, openness is a necessary precondition for seeking and identifying opportunities. The traits scale achieves the highest mean of all PVM variables, indicating that the specific traits are important for creating and exploiting opportunities to constantly improve the initial value proposition of a project. The high path coefficient and factor loading of the scale also demonstrates their importance for the measurement model of the PVM construct.

The results show, in sum, how important each of the six scales are for measuring a project manager's PVM. The importance of each scale was tested using two different tests (Principle Component Analysis and SEM) with two different levels of data aggregation, and both methods showed similar results. The results also demonstrate the complex nature of the PVM variable, and they underline the necessity to operationalize the construct in the specific context, in this case the management of projects.

The main hypothesis of this study describes the importance of a project manager's PVM for the creation of project value. This hypothesis was tested with the SEM method by estimating the strength of the direct path of the PVM variable on project value while simultaneously considering the influence of exploited value opportunities on project value. The high path coefficient is surprising and shows how important it is that project managers constantly manage their project toward improving its value proposition. The strong impact also indicates that project managers who seek to satisfice the initial project value proposition will likely fail to capture the potential project value. The openness to change demonstrated by questioning the initial requirements and seeking to improve the value proposition of a project is an effective strategy for facing uncertainty. This well-known companion of many projects could be addressed by seeking opportunities to improve the initial value proposition of a project.

The relatively high mean of the scale Exploited_Opportunities suggests that opportunities to increase the project value obviously occur and are exploited to achieve and create value. Initially, we had not anticipated two different scales for opportunities that are exploited during a project's implementation. We did not have any reference scales we could rely on. However, the results demonstrate the divide between the narrow TC-paradigm and the project value paradigm suggested by this research. It also highlights the limitations of the TC-paradigm and its underlying premises. All tools used to implement projects are supporting the project manager's efforts to meet the triple constraints. The strong impact of exploited value opportunities on the created project value, as suggested by the high path coefficient in Figure 2, demonstrates how important it is to exploit opportunities during a project's implementation.

An important precondition for exploiting project value opportunities is a project manager's disposition toward seeking and identifying opportunities by constantly questioning a project's requirements and being motivated to maximize a project's value. The proposed relationship between the PVM and the exploited value opportunities is supported by the high path coefficient (Figure 2) and the high level of explained variance (R2=43%). This means that, without a mindset to maximize the project value, promising opportunities to extend a project's value proposition won't be exploited. This link is crucial, as it points to the fundamental limitations of the TC-paradigm. The creation of project value via the exploitation of opportunities to increase stakeholder satisfaction is beyond the TC-paradigm. The results support the basic critique of the TC-paradigm that only the quest to maximize the value of a project will in the end lead to the achievement of a project's value potential.