ONE

Conceptual Framework of the Study

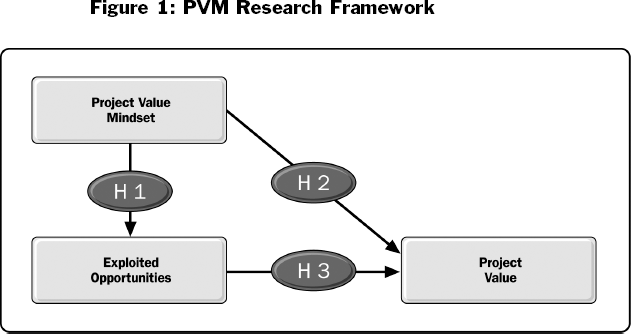

This chapter provides an overview of the different components that are considered in this study. Rather than conceptually developing the different components of the framework of this study, we start with the study's framework. This gives the reader a structured overview of the model discussion that follows in the succeeding chapters. The research framework of this study consists of four (4) variables:

1) Project Value Mindset (PVM)—describes the attitude of a project manager to maximize the value of a project by making value-focused project decisions and by seeking and exploiting opportunities beyond the baseline that will lead to increased project value.

2) Exploited Opportunities—those opportunities recognized and exploited by the project manager during the project implementation.

3) Project Value—defined by Efficiency, Scope, Stakeholder, and Shareholder satisfaction.

4) Project Situation—characteristics of the project which include uncertainty and complexity.

An overview of the relationships between the model variables and the research hypotheses are indicated in Figure 1.

The hypotheses are depicted in Figure 1 by the arrows, which describe the proposed relationships between the model variables. The study proposes to test the following hypotheses:

H 1: The higher a Project Manager scores on the Project Value Mindset scale the higher the likelihood that Project Value Opportunities are exploited.

H 2: The higher a Project Manager scores on the Project Value Mindset scale the higher the likelihood of an increase in Project Value.

H 3: The more Project Value Opportunities that are exploited by a Project Manager the higher the likelihood of increased Project Value.

The theoretical basis of the model variables and their proposed relationships are discussed in the following chapters of this study.

Project Success vs. Project Value

One of the main critiques of the TC-paradigm, as indicated above, is its incomplete representation of project performance/success. Johannes Ralph addressed one aspect well in an architectural studies design, called the Model for Architectural Design Education (MADE), at the University of Essen, Germany. “Quality is defined as the totality of features, attributes, and characteristics of a facility, product, process, component, service, or workmanship that bear on its ability to satisfy a given need: fitness for purpose. It is usually referenced to and measured by the degree of conformance to a predetermined standard of performance” (Ralph, 1992).

In general, the definition and measurement of project success are controversially discussed in many different contexts. One problem is, as Freeman and Beale (1992) point out, that “success means different things to different people.” This perspective is supported by the view that whether a project succeeded or failed could be an ambiguous determination (Belassi, 1996; Freeman & Beale, 1992; Pinto & Slevin, 1989). Other authors differentiate between project success and project management success (Baccarini, 1999; de Wit, 1988), or they add criteria that are industry specific—such as Pocock et al. (1996), who suggest that construction projects include the absence of legal claims as an indicator of project success. In the latter example, both contractors and clients may be subject to legal claims, as well as financial loss and contract delay, in construction projects (see also Kometa et al., 1995; Kumaraswamy & Thorpe, 1996; Songer & Molenaar, 1997).

Beside their different suggestions, most authors agree that project success is insufficiently defined by the TC-paradigm, yet a general definition is still not agreed upon. The problems of defining and measuring project success are related at the conceptual level, as many authors start with the TC-paradigm in mind and try to extend and supplement it. This approach does not change the basic principles under which the criteria are selected. Project success is still measured as an adherence to the triple constraints, with the addition of some other criteria that should be fulfilled to address “local” needs. It is measuring project success toward a baseline that is predetermined and defined before the project is started, and modified during the project execution. From a project manager's perspective, the challenge is avoiding variation from the baseline and the other success criteria. This approach does not necessarily lead to the value maximization of a project, and dissuades one from seeking or considering potential alternatives. A valid performance measure with this approach would only be possible if the project is implemented under completely determined conditions; that is, negative deviation would then be directly related to a poor management performance of the project manager or stakeholders. This also means that projects are successful if the baseline is met.

The main problem is that uncertainties are not taken into account. Contextual conditions of projects are changing constantly, and what once looked like criteria to define value could dramatically change; for example, a new product development project facing a competing product, which was started without the expectation of a competitor's product. The other problem is that the baseline has to be “realistic.” If it is too ambitious, a negative deviation is built into the project plan. Another less obvious and less discussed possibility is that a baseline is too low and it could be easily met. Still, a project would be claimed successful if the baseline were met. From the perspective of the TC-paradigm this means conceptually that the project manager needs to minimize the negative variation from the baseline but is not challenged to maximize the value of a project beyond the baseline. There is no empirical evidence about the practical magnitude of this conceptual problem.

The basic TC-paradigm principle to determine project success leads to critical conclusions, like successful projects not appearing as time and budget critical (Wateridge, 1995). In general, Which performance criteria are more important than others? is an incomplete question. This question needs to be modified, as the answer depends on the specific circumstances under which a project is implemented, and on the needs of the stakeholders. The question, “Which of the success criteria best reflects project value (e.g., time)?” is a very critical success criterion for consumer product development projects, as a delay might lead to significant losses of market share. However, time might not be as relevant for the implementation of ERP systems, where it is more important to create a stable and widely accepted solution. Additionally, the project budget can be an important success criterion, because significant cost overruns in a fixed price contract will lead to an overall loss.

The question has to be changed from a generic, normative perspective on determining project success with a general set of criteria toward a value-oriented perspective. Several authors have indirectly addressed this perspective. For example, the Thames Barrier project took twice as long to build and cost four times the original budget, but it provided profit for most contractors (Morris & Hough, 1987). The success of this project could not be explained with the TC-based approach. Turner and Müller (2004) suggest that project outcome should be measured and the project manager rewarded on a wider set of objectives, not just the achievement of time, cost, and functionality goals. They suggest considering a project's performance evaluation, that is, considering whether the project created satisfactory benefits to the project stakeholders, was implemented within budget and on time, and satisfies the needs of the project team. Others claim that a successful project should meet two criteria: (1) the degree to which the project's technical performance objective was attained on time and within budget, and (2) the contribution that the project makes to the strategic mission of the enterprise (Morris, 2005). Anton de Wit (1988) considers a project an overall success if it meets the technical performance specification and/or mission to be performed, and if there is a high level of satisfaction concerning the project outcome among key people in the parent organization, key people in the project team, and key users or clientele of the project effort. For Parfitt and Sanvido (1993), the specific project mission/goal includes technical, financial, educational, social, and professional issues.

The list of authors addressing project success evaluation could easily be extended. Although the discussions are TC-paradigm centric, the critiques of, and suggested extensions to, measuring project success have the common thread of pointing toward a different paradigm. It is widely accepted that a project is not necessarily successful if the triple constraints are met. Even though most authors see the budget, time and scope measures as important parts of the general set of project performance evaluation criteria, some of the concepts discussed demonstrate that it is important for a project to create a certain level of satisfaction. This leads, to some extent, away from a satisficing approach and points toward a maximizing paradigm.

Definition 1: Project Value

A project's value is defined by the value it creates for its stakeholders. The project value could be represented by one or any combination of the project's efficiency, technical effectiveness, and/or the satisfaction of its stakeholders, with emphasis on clients and shareholders.

As definition 1 suggests, project value is not defined in a normative sense; rather, it is defined in a relativistic sense, as the value of a project could be determined in many different ways depending on its specific context and situation. The question of whether the achieved project value represents a maximum could never be answered accurately. This question could only be addressed by evaluating the management process of a project from the perspective of the maximization paradigm. The expression “project value” was chosen to clearly differentiate it from the mainstream discussion of project success. A detailed conceptual treatment of the specific conditions determining project value is not essential for the discussion in this study.

A Project Manager's Project Value Mindset

In this section, we address the question of how a project manager's value mindset could be conceptually defined. When one hears the word “mindset” the thought that it generates varies substantially among many. Some take the Webster's Dictionary view that it is “a mental attitude or inclination” or “a fixed state of mind.” While others might proffer that it is “mental attitude,” “an opinion,” “a set of assumptions held,” “a way of thinking,” and even “a state of mind,” “an inclination,” or even “a habit,” to note a few of the more popular definitions. It is also noted that one's mindset may indeed be “set” or “fixed” for some, while for others it is deemed to be “growth” -oriented (Dweck, 2006). In all cases, one's “mindset” can only be inferred from his or her pattern of behavior; that is, the actions taken or the lack thereof.

In this study the mindset of a project manager is directly linked to the specific context in which projects are implemented. The specific characteristics of the mindset are derived from conceptual differences between the TC-paradigm and the PV-paradigm. One fundamental characteristic of the PV-paradigm is its maximization premise, in contrast to the satisficing premise of the TC-paradigm. Another premise is that uncertainty occurs during the implementation of projects and these uncertainties are the source of opportunities to increase a project's original planned value. The definition of Project Value Mindset (PVM) is based on these fundamental assumptions. It is obvious that PVM cannot be derived from one singular perspective; rather, it is a complex concept that is related to the different attitudes and traits of a project manager, as discussed in the following sections.

Project Manager's Opportunity Disposition

Uncertainties during the implementation of projects are more likely a general rule and not the exception. The strategic management literature amply points out that developing the plan addresses the market, while the implementation of the plan is an operations-based endeavor. As a functioning “crystal ball” is not available, one can only make best-guess estimates and establish contingencies for the uncertainties the plan implementation will most likely face. Economists argue that uncertainty is the conditio sine qua non for the existence of opportunities. Entrepreneurial activities only evolve if individuals are “alert” to opportunities, meaning they are actively seeking or are open for opportunities. Following this line of thought, it is imperative for project managers to seek out those opportunities that could significantly change the value proposition of a project. Within the TC-paradigm this activity would not conceptually be encouraged, as there are no incentives to increase the value proposition of a project. It should be clearly stated that this does not mean a project manager is NOT seeking opportunities in practice. But it is our basic argument that the search and creation of project value opportunities are not encouraged by the general project management approach and are not supported by the existing tools that are in compliance with the TC-paradigm.

The disposition for seeking and creating opportunities to maximize the project value beyond the predefined value proposition is a necessary attitude, being part of the project value mindset concept. This attitude includes the quest of a project manager to seek a project value maximum beyond the baseline of a project.

Project Manager's Overachievement Disposition

The attitude for overachievement is a defining component of the PVM and is consistent with the main critiques of the TC-paradigm. This attitude is to “overachieve” a given set of constraints or project objectives. Only project managers who try to overachieve the initial project goals demonstrate the motivation to seek opportunities. The quest for overachievement cannot be directly related to the TC-paradigm due to its fundamental integration of the satisficing approach. This is evident in the concept of trade-offs. The presumption we make here is that satisficing is always the case. The term satisficing means “close enough,” which therefore indicates that the TC-paradigm is never quite met. If maximizing is known, achievable, and acceptable, less than this would be satisficing. Our presumption is that no TC-paradigm is inherently correct or maximized, as there is no functioning crystal ball and there are always opportunities to do better. Therefore, given reasonable, achievable goals based on the TC, the results are always a degree of satisficing.

As discussed, projects face uncertainties, and under these conditions it is impossible to set project objectives that perfectly reflect the “reality” of a project. In a deterministic world it would be possible to define absolute project objectives, and the goal for a project manager would be to satisfy these objectives. The conditions are completely different under the premise of uncertainty. It is impossible to define ultimate project objectives. Changing objectives is a given, and a project manager who strictly follows the rules of the TC-paradigm would find it nearly impossible to achieve the full value potential of a project. In most discussions, uncertainty, as it relates to a project's value proposition, is seen negatively—for instance, the targets of the objectives have to be lowered or a greater safety margin is taken, thus adding cost or time. But, uncertainty, as discussed earlier, could also open the door to opportunities that could lead to a higher value proposition of a project. What if the initial project targets were set too low? In this situation the initial value proposition of a project would completely change, and a satisficing approach would not lead to achieving the potential maximal project value. If only the project manager would seek to increase the initial value proposition, he or she would be alert for opportunities and be willing to exploit opportunities.

Project Manager's Dialectic Requirement Disposition

For any project manager it is imperative to understand the “constraints” of a project, or the requirements and specifications laid out in a project charter. Often a project manager is charged with implementing requirements whose definition he or she was likely minimally involved in, if at all. In any case, project managers are charged with “finding” the best fit between the requirements to be fulfilled and a realistic process scenario. The traditional way to do so is to create a project baseline that meets the requirements best. Acting in compliance with the TC-paradigm, project managers calculate the Critical Path under the given resource constraints to assure a most promising project implementation process with a high likelihood of fulfilling the predefined requirements. This process of planning to comply with the constraints follows the satisficing premise. As discussed earlier, the best possible compliance to a given set of requirements would not necessarily lead to the best possible project results or, as we call it, project value.

But if the premise is changed from satisficing to maximizing a project's value, as the PV-paradigm suggests, it is imperative for the project manager to question the given project requirements and specifications. It is most likely that the externally defined requirements are not representing an “optimal” set of constraints or defining a “solution space” in which the maximal potential project value lies. Given that project managers have a certain level of expertise for recognizing the difference between intended requirements and predefined requirements, it would be important for the project manager to question the given set of requirements and put some effort into modifying and prioritizing requirements before and during the implementation process. Only a constant search for modifying and exceeding predefined specific requirements will lead to a potential possibility to maximize a project's value. The presumption is that the TC, as stated, is in many cases inaccurate, and that the project manager is capable of recognizing and implementing necessary changes. Failing this, a project manager would risk lowering a project's potential economic value, thus causing an increase in time and budget or a decrease of customer satisfaction. The questioning and constant validation of project requirements and technical specifications under the maximization premise seem to be essential attitudes in a project manager's PVM.

The initial project requirements represent the intended value proposition of a project. One of the main assumptions of the suggested PV-paradigm is the occurrence of uncertainties. The existence of uncertainty could be seen as the essential force for changes of a project's value proposition, requiring the project manager to repeatedly ask for refining, modifying, or changing a project's requirements with the intent to increase the potential value of a project. These changes might be necessary to create and exploit opportunities, thus allowing a project to achieve or exceed its predefined project value. The project manager's disposition to critically and constantly evaluate a project's requirements is an important attitude of the PVM concept.

Project Manager's Ambiguity Disposition

The creation and exploitation of opportunities are related to situations of ambiguity. Only those project managers who accept and are comfortable with ambiguous situations will be able to exploit opportunities. The disposition to tolerate ambiguous situations was defined by Budner (1962) as an individual's propensity to view ambiguous situations as either threatening or desirable. Since this hallmark study, tolerance for ambiguity has been associated with numerous markers of success (Bauer & Truxillo, 2000; Johanson, 2000; Lauriola & Levin, 2001) and also with open-mindedness (Furnham, 1995). From these perspectives a project manager's disposition toward ambiguity could be seen as a precondition to exploit opportunities. In contrast, an individual who seeks to avoid uncertainties and changes tries to anticipate changes. This is supported by Dugas, Gosselin, and Ladouceur (2001), who associate intolerance for ambiguity with an individual's number of anxiety-related problems, including worry, obsessions/compulsions, and panic sensations. Applied to the management of projects, this individual analyzes constantly, looking for potential sources that could cause changes.

A disposition toward ambiguity is related to the direct treatment of uncertainty and is thus an essential facet of a project manager's PVM, as it is supported by the general literature on ambiguity.

Project Manager's Personality Traits

The attitude an individual displays and acts upon is intertwined with one's personality and, to some degree, with an individual's intelligence. Intelligence is a general concept that underlies nearly every human behavior and is not specific enough for the PVM concept. The traits of a project manager are more specific and are easier to monitor, as the discussion on how to measure intelligence has not yet converged on a generally agreed concept. The common traits typology consists of extraversion and stability,6 as well as conscientiousness, openness to experience, and agreeableness. Other personality traits that are important to the project manager include an ability to be comfortable making decisions under ambiguous situations. It is the nature of the job for a project manager to “multi-task,” or to address many variables concurrently, and they are required to make good decisions when all the information isn't present. Therefore, project managers must be tolerant of ambiguous situations. project managers are also challenged in this regard with having to address multi-level issues, ranging from technical specifications, to time, finances, stockholders and stakeholders.

A person who is predictable is expected to act appropriately in a given situation and is seen as more trustworthy than one who is likely to overreact. A person who is very stable is able to make a reasonable decision when the telephone is ringing, the boss is yelling, the computer server just crashed, and the coffee is burning. A person who scores low in this measure tends to lose focus, overreact, and find it difficult to make decisions and maintain control.

Under conditions of uncertainty and value maximization, the tendency to seek and exploit opportunities is an important characteristic of the project manager's mindset. For example, if a project calls for a high degree of creativity, due to a large number of unknowns, that project might be better served by a project manager who is somewhat extroverted and has a higher degree of openness. That is, one who likes to work with others and will seriously consider their views.

One is likely seen as having a “good personality” if he or she is engaging and has an ability to draw others in to achieve results. A highly extroverted person tends to have difficulty working alone and “needs” the company of others. But someone who is not comfortable working with others is less likely to attract the cooperation of others. Thus, a highly introverted person may have a difficult time “stirring the troops to action.” Since projects are highly collaborative efforts, a project manager's people skills (traits) are essential for integrating the different viewpoints of team members. The likelihood of creating and discovering opportunities in the specific context of projects is much higher if the individual's personality is to some extent open and extroverted.

A conscientious person is highly desired, because this person does what they say they will do; a high degree of trust and confidence is felt by all. On the other hand, one who is less than conscientious may agree to do something but is either late or doesn't “get to it.” Strangely, a very high score in this area might be seen as great, but it also has its issues. A highly conscientious person may be so focused on doing what needs to be done as requested or agreed to that he or she may find him or herself overcommitted and under duress. To use an old saying—too much of a good thing [is bad].

A person who has a higher degree of openness is willing to seriously consider the views of others. So opinions about alternate strategies are welcomed and often encouraged. Those with high scores in this regard can be seen as seeking out information, reading, asking questions, or—as a colleague pointed out—some are “perennial students.” So, while seeking knowledge is a strong plus, it poses a problem when one continues to seek information, and fails to make a decision. The project manager may be trapped by “analysis paralysis,” a continual need for more data before making a decision.

Agreeableness is nice—we all like to work with “agreeable” people, as they “understand” us and they validate our views and expectations. The person with a high degree of agreeableness is interested in pleasing others, so it is easy to see why he or she is liked in many ways. However, when a decision needs to be made—and that is a critical requirement for the project manager—the “agreeable” project manager's decision could be influenced by the potential impact it will have on the other party, rather than by what is important for the project or company. The highly agreeable person may find making adverse decisions, ones that displease others, difficult, with the expectation that the affected party may perceive the situation more negatively than they actually do. Of course, a person who is low on agreeableness will make decisions with less consideration of the feelings of others. So, while an agreeable person is well-liked, and this trait can engage others, extreme scores in this area may be disadvantageous.

As demonstrated above, a project manager's traits can be linked to the decision process and thus are an important facet of the PVM concept.

Project Value Mindset Definition and Conclusion

The discussion of the different components of a project manager's PVM suggests that it is a complex concept including several aspects influencing the decision preferences of project managers in relation to creating and achieving project value. In conclusion, we could summarize the PVM of a project manager in the following definition:

Definition 2: Project Manager's Project Value Mindset

The PVM of a project manager is a mental state involving several dispositions and attitudes resulting in activities to seek, discover, and create opportunities beyond a predefined value proposition, with the intent to maximize a project's value.

The definition indicates that the PVM is a complex mix of personal characteristics, dispositions, attitudes, and context, the result of which is strongly situation-dependent. The definition is sufficiently general in the sense that it could be applied in a different context, e.g., an entrepreneur starting a new business. However a too-general definition would not serve well for studying the impact of the mindset on project performance, e.g., the mindset of an athlete. At the same time, the definition is specific, as it is related to the situation of the project manager, and it acknowledges the constraints of the TC-paradigm. This is particularly important, as a general concept of mindset would not adequately represent the issues particularly related to the TC-paradigm. The PVM is defined in contrast to a TC-related mindset, and it questions the underlying concept of the satisficing concept as it is embodied in the TC-paradigm. In contrast, the PVM is based on a maximization approach of focusing on the maximization of project value. This direction is very specific, but it is necessary to relate specific behaviors and decision patterns that go beyond the specified requirements at the beginning of a project.

Project Value Opportunities

The creation of economic value is closely related to the exploitation of opportunities and, consequently, an important variable for the project value paradigm. The existence and nature of opportunities have traditionally been covered in the economic literature and has not yet been considered by project management researchers. It is argued that the occurrence of uncertainties is a major precondition for the existence of opportunities within an economy (Kirzner, 1973; Knight, 1948; and Schumpeter, 1934), and it is understandable that without uncertainties entrepreneurial profits (extraordinary profits) would be impossible. In addition to uncertainty, other preconditions include the existence of resources and entrepreneurs who recognize, create, select, and ultimately exploit opportunities (Timmons, 1999).

Surprisingly, the term “opportunity,” although commonly used, is—even in the economic and entrepreneurship literature where opportunity recognition and exploitation is a tenet—not well-defined. Shane and Venkataraman (2000) define the root of entrepreneurial opportunities as: “situations in which new goods, services, raw materials, markets, and organizing methods can be introduced through the formation of new means, ends, or means-ends relationships” (p. 336). Innovation is the sine qua non for opportunities that leads to or is related to uncertainty and is also a major characteristic of projects.

The bottom line is that projects, as they all face uncertainties, are predestined to experience the emergence of opportunities and subsequently the recognition, evaluation, and exploitation of an opportunity during their implementation. This is a major concept of the project value paradigm, as it is the source for maximizing project value. For our purpose, we focus on those opportunities that occur during the implementation phase of a project, and we define project value opportunities as:

Definition 3: Project Value Opportunity

Project Value Opportunities (PVO) represent a potential to exceed the predefined stakeholder value of a project during that project's implementation.

This definition is closely related to the previously discussed project management paradigms. The project management literature acknowledges the concept of project risks (known-unknowns) and suggests many different approaches to analyze possible sources of project variation. Under these conditions, it is possible to avoid or mitigate risks by describing them either qualitatively or quantitatively. The TC-paradigm addresses these sources of variation by analyzing tradeoffs and their consequences for the project results; however, it does not address the concept of uncertainty. As previously discussed, the TC-paradigm also does not include the notion of maximization. The issue of satisficing is an inherent characteristic of the TC-paradigm and, from this perspective, uncertainty on the project level is a threat. But as Baumol (1993) pointed out, situations of uncertainty defy any optimization calculus. Thus, we conclude that under a paradigm of maximization, project uncertainties are also related to opportunities and, if exploited, will exceed the predefined project value.

6The Five-Factor model of personality typically includes neuroticism. We note that “stability” is seen as the inverse function and is a term many are far more comfortable with.