Computers and the software that run them have a limited life span. And when business requirements are changing rapidly, driving aggressive development and change in the supporting technology, pressure grows to enable business processes and support clients with the advantages of new technology.

That was what we at O.C. Tanner faced. We had in place aging mainframe computers and the associated software that went with them. By the late 1990s, it had become clear that this technology was inhibiting our success and it was time to move to client-server-based hardware and state-of-the-art software.

To understand how the use of the One-Page Project Manager (OPPM) evolved over the life of this project, you need some background. We called the project Cornerstone, since IT supported business processes are a cornerstone of our business, and this project involved deciding what to buy to replace our legacy systems and then installing it. For a year prior to launching the project, we evaluated various hardware platforms and software packages. We hired top-notch (and pricey) consultants to help us.

At the end, we decided to move to a three-tier client-server environment, replacing our DOS-based environment with a graphical user interface. As IT people know, the three tiers are the client tier, the application tier, and the database tier. Specifically, we chose: a hardware platform from Hewlett-Packard (HP) which included servers, PCs, and the like; a front-end package that does sales, orders, and pricing functions from Trilogy; and an enterprise resource planning (ERP) package from SAP that provided back office and financial functions.

We started planning for this project in early 1998 with our consultants, the Gartner Group, and launched the implementation project in January 1999. The goal was to complete the project by the end of 1999, in time to deal with Y2K. Helping us implement the project was the consulting arm of Arthur Andersen. The budget for the entire Cornerstone project: $ 30 million.

An important point to remember: The OPPM sits on top of all other tools used by the project manager. It does not supplant others and must be correlated with and aligned to the other tools used in projects. An OPPM was used initially in 1998 to manage Gartner 's efforts to select the vendors. What was supposed to then be a one-year deployment turned into a multiyear multiproject. For the multiyear implementation project, we decided to create a different OPPM for each year as the project proceeded. In the beginning of 1999, for example, we used an OPPM involved with the design and deployment of the back office, front office, and financial software packages on HP hardware. Since we knew very little about the newly acquired technology, the OPPM principally covered a consolidation of methodologies and project plans supplied by the various vendors.

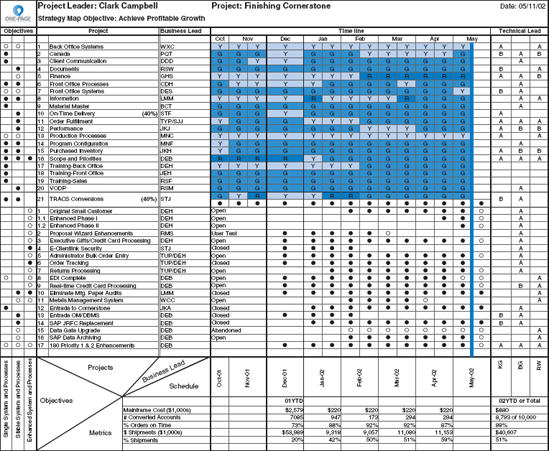

There were different OPPMs for 2000, 2001, and 2002 as well, each reflecting a little more learning on the part of our project team, and therefore both a refinement of and a growing departure from "vanilla" methodologies. The example we use in this book is the OPPM for 2002, the final year of the Cornerstone project (Figure 6.1).

Let me stop and confess right here that our Cornerstone project is a story of how we recovered, along the way, after some very serious mistakes. It is a saga of how we learned from our stumbles and struggled to turn them into the proverbial stepping-stones.

During the early stages of the project, we invited Todd Skinner, rock climber and author, to speak to us. Todd Skinner is credited as the "most accomplished rock climber of this generation." Of his 300 first ascents in 26 countries, it was his spectacular 60-day free ascent of the east face of 20,500-foot Trango Tower in the Himalayas that inspired us. We were in awe of his determination and stamina, and we were personally tutored by what he learned "on the wall" :

Copyright O.C. Tanner 2008. To customize this document, download it to your hard drive from the following web site: www.onepageprojectmanager.com. The document can be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Excel or another popular spreadsheet application.

"The mountain is the catalyst that transforms a group into a team."

"What you don't know, the mountain will teach you."

"Each mountain is made up of rope lengths, and each rope length is made up of single steps."

"It's not if you fall . . . but the knowledge you acquire from the fall and the way you apply it."

"The severity and duration of a storm are less important than mind-set, momentum, and morale.

Many times while "on the wall" of our Cornerstone project, we referred back to Todd Skinner's insight to help us maintain our tenacity, courage, and focus on the summit.

Now, back to the facts. Actually, this project had its earliest beginnings in 1997, when we began considering how we would reengineer our business. This was a project that would transform our entire enterprise. At this early stage, we laid out three phases for the entire project:

An analysis of our current business model, a potential future state, gaps, and a future IT assessment;

Request for proposal (RFP) to vendors to implement our assessment; and

A high level migration plan to take us from where we were with our legacy system to where we would decide we wanted to be.

By 1998, we were using an OPPM to go through the process and analysis of software and hardware to decide what would be right for us. This was then followed with RFPs and scrutinizing the responses, including studying proposals and testing demonstration projects. And then we negotiated and signed contracts with vendors. All the while, the OPPM communicated our progress.

On January 2, 1999, our board of directors approved the project. Then the implementation project plan started. The OPPM took the high points of each deployment plan from each vendor—SAP, Trilogy, and HP—integrated them, and then wrapped that around how Arthur Andersen would guide us through the transformation. As of April 1999, the financial portion of the project, which was part of the SAP deliverables, went live (on time) for all financials. This was ahead of Y2K, which was important. At around this time, our CIO resigned and a new one was hired.

By December 1999, we realized that the work would be substantially more difficult than we had thought. The 1999 OPPM was largely a compilation, integration, and alignment of the varying plans of the different vendors; these were not well integrated. They were more a parallel series of separate projects, yet not tightly interwoven. Vendors remained committed to their unique methodologies, unwilling to compromise enough to bind into an interdependent whole.

In 2000, it became clear we would have to launch out on our own. The OPPM was the document we used to help us navigate through these issues.

At this time, we launched Cornerstone Lite. Originally, we were advised to do a Big Bang conversion—turn off the legacy system and then turn on the new client-server system over, say, a single weekend. After our experiences with the project the first year and all we had learned since we started Cornerstone, we decided that to shut-it-off-one-day and start-it-up-the- next was far too risky a strategy. We were also not in a position to execute a series of "little bangs." The remaining modules were dependently connected, and we didn't have a fully functional small division to learn from. That's when we devised Cornerstone Lite. We would continue using our legacy system in parallel with the new system as it was gradually eased in. All new business and all new customers would be built into the new system while our existing business would remain on the legacy system and be converted over time.

Adding to the challenge was the decision, in 2001, to launch a new dot-com business (discussed in the previous chapter). This business would be built on the new platform since we were planning to eventually get rid of the old. This meant that not only would we do a Cornerstone Lite while we carefully converted existing clients to the new system, but also we had to add an entire new business at the very same time.

By deciding to go with Cornerstone Lite, we made the commitment to have two systems operating in tandem as we went through the challenges of converting our existing business over to the new system. In the middle of 2001, we had some vigorous debates over the desirability of doing this. If you are familiar with transformation projects such as Cornerstone, it will come as no surprise that our consultants, and just about anyone else we talked to, said we should never run two systems at once. Nonetheless, we did. And we are thankful we did.

Keep in mind that in 1999, as was reflected in our OPPM, we had a collection of projects that were aligned according to the plans of various vendors, as I mentioned earlier. By 2000 and 2001, we had to slowly disconnect from their plans (which were based on the Big Bang strategy) and connect to our plans. The owners of the project, as shown on the OPPM, went from being consultants to being a combination of O.C. Tanner employees and consultants, to finally being O.C. Tanner employees exclusively. By the end of 2001, all the business and technical leaders came from in-house—and all the consultants moved on. Not only were all the consultants (and at their peak, we had 60 consultants on our premises) no longer business or technical leaders, they were gone. Period. We brought the entire project in-house. We had also exhausted our consulting budget.

The tasks, as specified on the OPPM, went from being delineated by the vendors, to tasks that our own team drew up and committed to completing. By this time, our people had gone through an aggressive learning curve; it was trial by fire. The team knew much more of which we needed to accomplish and how to measure it. The mountain was teaching us what we needed to know.

Let's talk about how expenditures evolved. Early in the project, most costs were for software and consultants, many of whom were brilliant and absolutely indispensable to our success.

They came from SAP, Arthur Andersen, and Trilogy. By the middle of project, most costs were associated with the purchase of HP hardware. And by the latter part of the project, costs were largely those associated with our own people.

The time lines, as reflected in our initial OPPMs, were taken on faith as bestowed on us by the consultants. We worried about these time lines, but trusted the consultants. As we progressed and better understood the software, hardware, and the challenges involved, the time lines became more and more determined by O.C. Tanner and less and less by the consultants.

Notable was how the attitudes and feelings of ownership of people in our company changed. In the beginning of the project, our people would talk about the project by saying, "they said this," or "they did that." The "they" were the consultants. As the project progressed, our people started talking about "we think" and "we know." There was a remarkable infusion of ownership within our company. The mountain was the catalyst.

In addition, the subobjectives changed. At first, meeting the time lines was very important because time lines were tied to costs and the longer we went; the longer we needed the consultants (I won't mention the dollars involved, but trust me, those scores of consultants were not cheap). When the time lines were under pressure, we would do tradeoffs—we would limit scope so we could meet deadlines. We reached a point where we didn't want to do that anymore. We were cutting into muscle. By moving to our internal people who could do what the expensive consultants could do for a lot less, our priorities shifted from meeting deadlines to achieving the scope we needed so our business could run efficiently and competitively. Of course, our people could not immediately do what the consultants could. This forced our people to reach beyond their grasp. We really did not have any choice: We could not afford the full brigade of consultants over a protracted period of time.

We abandoned the recommended go-live methodology—the Big Bang. We decided to operate our two systems in tandem because stability and scope were more important than the time line. The new robust functionality we wanted to offer our clients could only be rapidly achieved through our Cornerstone Lite strategy. Once the project was brought in-house and costs contained, the timing was not pressed by the budget. We were able to add functionality. This became important. In fact, we allowed some scope creep, such as the building of the Internet business right on top of Cornerstone.

Prior to the decision to proceed with Cornerstone Lite, several planned go-lives were announced and then eventually abandoned. We nearly fell off the mountain. However, at that moment, four critical elements came together to open a new path:

A patient and encouraging board and senior management that was communicated to honestly each step of the way by OPPMs.

A weathered, enabled, and determined team on the wall that was committed to seeking a "future better beyond our present best."

A change in methodology—to promise the delivery of just a chunk—Cornerstone Lite for newly acquired accounts only.

The absence of the go-live pressure of the expensive consultant run-rates.

Cornerstone Lite came live on time as promised! Chunks of conversion were now planned.

The new level of functionality began to manifest itself as the project progressed. As new customers came onboard, they were placed on the new system. Gradually, old clients were converted to the new system. On-time delivery, the amount of orders entered, the amount of orders shipped, order accuracy, inventory levels—these general business metrics became critical to the project as performance and stability measures.

With the growth of the OPPM structure, we recognized that a greater number of our objectives were subjective rather than objective. For example, initially, we might have asked about a part of the system: Is it now live? This would result in a yes - or - no answer. But a subjective objective would be: When you hit the button, does it work? "Work" is a subjective concept. Subjective colors become more dominant on the OPPM. The OPPMs of the early years were filled primarily with dots—objective time lines and milestones. Some of our contracts were fixed-fee, also driving consultants to give higher priority to time line over functionality.

Another major change related to the business. In the first part of the project, we carefully monitored consultant costs, but in the latter part of project, that cost tracking almost went away because the costs were now the costs of our own people. We went from managing the costs of consultants to managing the system performance and the metrics of our own business.

Where objective tasks are generally at the top of the OPPM, subjective tasks went to the top of the Cornerstone OPPM, reflecting their importance. In the color boxes, there are also the letters Y, G, and R. Because so many people were following the project we didn't want to incur the expense of printing the OPPMs in color for everyone so we used letters (Y = Yellow, G = Green, and R = Red) allowing us to use black and white photocopies to communicate.

In the lower left-hand corner of the OPPM, we divided the final portion of the project into three objectives:

Single System and Processes (this refers to us getting all our information technology running on one system);

Stable System and Processes (the system and processes would be stable and predictable); and

Enhanced System and Processes (the new system would be enhanced, expanded, and more robust than the system it was replacing).

This project had two types of owners, rather than the usual one—a lead-pair. Each component needed a ERP Implementation business owner who was someone from the business side of the company—client relations, customer service, manufacturing, accounting. These were the people who use the system. In addition, there was a technical lead, an IT professional, the person who managed the programming and implemented the system. One of the many things we learned while "on the wall," was this concept of a lead - pair. The natural tendency was to allow the technical person to lead by default since they understood the technology. This led to robust programs that were inadequate for the users. Consultants advised us to always have a person from the business side to provide the final say. This led to inefficient programming and technical architectural problems. A few technical leads each connected to the larger group of business leads all indicated clearly on the OPPM facilitated an "equally yoked" commitment and mutual cooperation.

Let's look at the project on line 3 (again, printing a color copy off the web will assist you here): Client Communication: Business Lead DDD is in charge of this task from the business side. Under Technical Lead, there is an A in the second column, indicating Technical Lead BG has A (primary) responsibility for this task. The two leads work together to bring this task home.

Notice that in December 01 on the OPPM, the Time line box is not divided into two as it is in the other months. By dividing each month into two, we are saying we will measure our performance twice each month, but in December, we will measure it only once (because of the holidays).

Take a look at the project on line 5: Finance. Notice it went red in the second half of February and now, in May (at the time of this OPPM) it remains red. This means the Finance project continues to be a problem. Also notice that this project has two A technical leads. We sometimes use multiple leads on technical projects, but we do not use multiple business leads.

Consider Project 21: Account Conversions, which refers to converting clients to the new system. In boldface type is written (40%). This is the amount of incentive bonus tied to this deliverable. The Project 10 line shows another 40 percent aligned with recognition award on-time delivery, while the remaining 20 percent, not seen on the OPPM, is for individual performance. We wanted to motivate our people to convert clients to the new system but not at the expense of client satisfaction. It felt as though we were expanding our capacity just barely ahead of demand. Even though project scope and client care took precedence over the original time line, the necessity of a continued focused attention on timing was required in order to drive accomplishment and preclude scope creep.

Project 21 sits between the subjective and objective tasks because it is both qualitative and quantitative. This is why it has two lines indicating how it is progressing. The black dots indicate we are doing okay on the number of planned conversions. The different colors are in reference to the quality of conversions, such as their stability and accuracy. While the performance here was a bit shaky between November and February where you see red and yellow boxes, from late February on, there is only green, signifying the conversion process is going well. In fact, partly as a result of his performance on this task, amplified by the visibility of the OPPM by senior management, Business Lead STJ was eventually promoted to vice president. This is an example of the OPPM serving as a wonderful way to communicate outstanding performance.

Note that the Proposed Wizard Enhancements on line 2 of the quantitative tasks is seriously behind schedule. Several other quantitative tasks (see lines 4, 6, 10, 13, and 14) have been completed and closed.

The first line under metrics is Mainframe Cost ($ 1,000s). This refers to the monthly lease payments for the mainframe in thousands of dollars. The nonconverted accounts are resident on the mainframe, and when conversion is complete, this mainframe cost will be terminated.

The second line, # Converted Accounts, tells in the first column the number of accounts converted in total, and the subsequent columns show the number of accounts converted in each month. Line three % Orders on Time, is a reference to the percent of orders delivered on time. On-time delivery was a problem with the legacy system. Now the percentage of on - time deliveries is improving, though there was some back pedaling in April. I am delighted to say that as this writing in 2008, on-time delivery continues at better than 99%, substantially better than prior to Comerstone.

The next line, $ Shipments ($ 1,000s) is the amount of shipments in thousands of dollars resident in the new system. The next line refers to the percentage of a year's shipments the previous line represents. In the first column, 01 YTD (year to date), it says that 20 percent of the year's shipments totaled $ 53,989,000. As shipments are added in each month, this percentage increases 42 percent in January, increasing to 59 percent by April, or 51 percent of all orders, January through April.

In the lower right-hand corner, 02YTD or Total, you find the total for the year to date for 2002. For Mainframe Cost, the total is $880,000. For # Converted Accounts, there have been 8,793 accounts converted out of 10,000 which is the target number for the year. With % Orders on Time, 89 percent of the orders year-to-date have shipped on time. Year-to-date, $40,607,000 worth of orders has been shipped (Jan. 02 through April 02).

How is the project performing? The OPPM shows both the six-month history as well as the current status middle of May.

It is easy to see the history of challenges and victories over time for qualitative projects 1 through 21 noting that in December half were yellow or red, and by the time of this report only 3 yellows and one red.

The quantitative measures are also clearly seen: 4 are ahead of schedule, 5 are complete and closed, 1 is abandoned, and 3 are behind schedule.

To be quite candid, this level of performance was not always the case. The OPPM for the earlier years showed an abundance of red and some substantial lateness across a large group of tasks. Our CEO kept the following posted behind his desk:

In the beginning of any project there is great

enthusiasm,

followed by doubt,

then panic,

searching for the guilty party,

and finally punishment of the innocent,

and rewarding the uninvolved.

During some of the darkest days of the Cornerstone Project, this reminded us that we were "on the wall" together even when the wind howled, the snow raged, and our ropes were frozen to the face of the mountains.