This chapter is largely about the investment advice of managing a portfolio, picking stocks, and avoiding common mistakes. It isn't about knowing something others don't with the Three Questions. By now you've seen the Three Questions at work. I've demonstrated examples of what I've learned over the years with the Questions. Chapters 5 through 8 were largely example after example of looking at the world through the Three Questions. I hope you can start investing by seeing things others don't. I hope you can see things I can't.

But we're not done yet. As Chapter 3 hinted, one tool to stay disciplined with the Three Questions and keep your scurrilous brain in check and not be humiliated by TGH is having a comprehensive strategy driving decisions. Just using the Three Questions is great! But a strategy provides a basis and framework from which you can ask the Three Questions and make small (or big) bets keeping you on path toward your goals.

Maybe you think you already have a pretty good strategy. Fair enough—but many investors who believe they have a strategy actually confuse tactics with strategy. For example, some investors want market-like returns with low fees, so their "strategy" is buying no-load mutual funds. That is a philosophy, not a strategy. Operating that way without a strategy, 10 years later, you won't have paid any load fees but you won't have gotten great returns. A strategy would involve planning what funds and why and how to change them.

Another misguided tactic is static asset allocation. A static asset allocation is the rigid adherence to fixed percentages of stocks, bonds, and cash. Brokers and the media have preached static asset allocation for decades. It's a fine self-control mechanism for people who otherwise lack self-control, just like having someone else prepare all your meals can control your weight if you can't hack it on your own. But static asset allocation ensures you can't take advantage of the Three Questions when opportunity knocks.

Investors also use stop-losses and dollar-cost averaging (both self-control mechanisms and also provably losing strategies which I detail in the box), buy and sell options and covered calls (another losing proposition in another box), short here, go double-long there, all believing they have a strategy that works, not realizing they're just spinning their wheels with tactics. Some, fine. Some, not. But tactics. A gaggle of fancy but ineffectual tactics do not a strategy make. There is nothing wrong with deploying any particular appropriate tactic at a given time. But it's no more a strategy than a carpentry tool like a hammer is a blueprint for a home. What's more, what is the point of using tactics if you don't know something others don't? You only want the hammer when it's the right tactic to accomplish the strategy. You're far better off using the Questions to figure out something others don't know, and using that knowledge to get ahead rather than losing your money in a slow trickle through tricky investment tactics without a strategy.

A strategy is a plan guiding your every decision. It keeps you disciplined when you're tempted to stray. The market simply isn't intuitive—one reason so many fail at it. Usually what's right feels wrong; and what feels wrong often is right. This is why you need the Questions and a strategy to keep your brain in gear.

Before you begin thinking about a strategy, let's establish a few ground rules about what you can hope to achieve. Ask anyone what their investing goals are and you'll find a plethora of confounding answers. Think of your own goals. Can you describe them in four words or less? If it takes 10 pages with accompanying visuals, you've been swayed by a financial salesperson who wants you to believe you have unique goals unlike those of millions of others—ones requiring a stunning array of fancy financial products.

No, it should be fairly straightforward. Investors have long been instructed by the financial services industry to categorize their goals across a broad spectrum of often confusing or conflicting categories. If you've met with a broker or a financial planner, they probably asked you how "risk-tolerant" you are. Most investors don't know and aren't trained to quantify their own risk tolerance. They see it as one thing after a bull market and very differently after a long bear market. Your inquirer may have had you fill out a questionnaire to determine what kind of investor you are—which really reflects how you feel that day. Are you a "growth" investor or even "aggressive growth?" Are you "growth and income?" Maybe they had you pick from a selection of colorful pie graphs or rank yourself on a scale of 1-to-7, or 1-to-10, or 1-to-37.

Here's the dirty secret. These so-called risk rankings don't mean anything—simply reflect no reality. So-called "risk tolerance" for anyone varies when confronted with varying circumstances. The same folks who filled out questionnaires in 1999 saying they were highly risk tolerant and sought 20 percent returns year-after-year, in 2002 and 2003 were saying they were risk averse and merely wanted low, safe, absolute returns. But it gets much more detailed than that. Most people are simply unable to assess how risk tolerant they are any more than most people who've never taken a hard punch to the gut can know how they'll feel emotionally after one—until it happens to them a number of times and various ways—like a boxer. I used to be a boxer and I know from my gut.

I've met few investors who really had a good handle on their risk tolerance. Most simply haven't a clue; they just have a feeling at a point in time. Their sense of their risk tolerance is molded by what they've read recently, what has happened to them recently, who they're talking to, and what they think they're supposed to say in response to such questions. Often it's different if they're with their spouse and offspring or not. It's a lot easier for a guy to fancy a pirate's lifestyle buccaneering the South Seas for adventure and booty when he's alone watching a pirate movie than with his wife. Pretty often you ask a man how risk tolerant he is, and he says he is very risk tolerant and can handle volatility. Later you meet the wife and describe her husband as risk tolerant and she laughs. I kid you not. Happens all the time. Is the husband wrong? The wife? Everyone is wrong because they all treat risk as if it were a uni-dimensional metric. It's not!

As Meir Statman and I demonstrated in a scholarly article titled "The Mean Variance Optimization Puzzle: Security Portfolios and Food Portfo-lios,"[173] risk is multifaceted and virtually impossible to fully comprehend in any moment for anyone. Your brain deals with investing risk just like it does with food and diet. Eaters and investors want at least six things at once—in both investing and their next meal. The risk they feel at any time is tied to whichever of those things they're not getting without regard for how they would feel if they didn't get the things they are getting. Your brain just can't put it all together at once—it fixates on what it isn't getting and to you that's risk.

I won't fully rehash that article here. But investors not only want return, of course, they want to keep up with the Joneses, or not to suffer from excess opportunity cost. This is why the person who envisions he only wants 10 percent a year actually feels angst when the market is up 35 percent and he is only up 20 percent. It's risk. Investors also fear volatility and see it as risk. It is. Finance theory has been excessive in portraying volatility as the risk measure. But it's just one risk and preys more on some than others. Of course, investors want pricing. Different investors want the pricing differently but they feel risk if it becomes inconsistent with their sense of what it should be. They want packaging. Packaging ripples into all the other risks, but includes presentation, ease of use, and part of the sense of confidence implying safety and less risk that is basic to all marketing. They want prestige. Prestige can mean many things including branding (appealing to that sense of uniqueness), a general sense of safety or lack of risk from perceived quality, and a sense of higher social order than others. Another way to think of this is "bragging rights," that is, "I got in on Google's IPO and you didn't." But if you take the prestige away suddenly it feels like risk to them.

Then they want order preference. Few appreciate how important order preference is to everyone but you can see it two ways in diet. One is why people eat breakfast foods in the morning and dinner foods at night—why not switch them around? Same calories and yet people largely obey order even when no one is looking. The second is how people don't experiment with the foods they combine. Why not try putting salad dressing in your coffee and cream on your salad or even your steak to see how it would taste? Might be better! You don't try because it violates order preference. And if you tried that in public at a restaurant, the people with whom you dine won't dine with you again. They would think you were a nut.

My point is, at any moment, the risk you notice and fret is associated with what you're not getting. And you can't make your brain realize all the other things that you are getting and how you would feel—how you would experience the risk—about not getting some combination of them. Very few folks have any real clue of how they'll feel confronting risk in the future. At this point it has never been measured in a meaningful way domestically or overseas, but I'd guess, and it's only a guess, less than 5 percent of society has a real clue about their risk tolerance and I'm delighted to include myself in that other 95 percent. And I'd bet you're in the other 95 percent too.

Another important point is the questionnaires and the "investor-types" and the colored charts and graphs aren't for you. They're for the salesperson and his firm. For the salesperson, "risk tolerance" translates into, "Number one—what is this sucker likely to buy? Number two—what will cover my tuckus when he tries to sue me later?" It's a sales technique and a legal defense technique—little more. Once they know how you categorize yourself, they know not only what to sell you but how to defend themselves under the "Know Your Client Rule" if you attack them later in court or arbitration. Having engaged in this catechism doesn't mean the things they sold you were appropriate for you. Only that you were inclined toward whatever it was that particular day. Strawberry, please, not chocolate.

You're a unique, wonderful person, I have no doubt; however, you're probably unique just about like everyone else. You're not statistically unique. In a statistical sense, being unique is to be way, way out the end of the bell curve on some set of attributes. If you're really unique, you're technically quite weird. Unique means weird. Most folks like to think of themselves as unique. They don't like to see themselves as weirdos. You probably share extremely similar investing goals with about 98 percent of humanity.

What you have are goals that feel unique to you but almost certainly are very similar to most people. The people who are most certain they're unique are almost always by definition narcissists. Narcissists always think they're unique which by definition means they're not. It's just a cognitive error. But society commonly says everyone is unique. It's touchy-feel-good and politically correct! The financial services industry sells into that with a blister of products supposedly suited uniquely to you. You're not unique unless you're weird. The real and common investing goals people have are quite straightforward, and you don't need a questionnaire or a graph to figure them out. Here's what they are.

You're either looking to grow your portfolio to fund retirement, to purchase something now or in the future (a first or second home, a college education, or a boat perhaps), or to pass to loved ones or a favorite charity. You might also think of this goal as "growth." But "maximizing terminal value" isn't necessarily increasing your pot of money. You might be drawing down more cash to spend each year than your investment returns generate—purposefully shrinking your pot of money—yet you still need to stretch your assets further. For example, a common response when asking someone what the primary purpose of his or her money is that it's to take care of him or her and the spouse for the remainder of their lives. That may involve growing their total money or simply stretching it. But it's probably the most common single case among investors everywhere. Very real! Very basic!

Many investors say the purpose of their money is to provide "income" to cover living expenses. They want some level of income or cash flow now or in the future. In an extreme example, some folks might be very happy if Daddy simply died and left a guaranteed income stream and they had no say in the investments and not necessarily any knowledge of how the assets are invested. Just like Gertrude Stein. Party time!

Of course, the party-time inheritor isn't really concerned with "income" as that term is technically defined. What she wants is predictable and secure cash flow. This is right and as it should be. Finance theory is clear we should be agnostic about our preferences for type of cash flow on a real, tax and risk-adjusted basis. For example, after-tax, we shouldn't care if our cash flow comes from dividends (which may be risky or not) or capital gains (which may be risky or not). Income streams are neither better nor worse for generating total return than capital gains. We should care about total return after adjustment for tax and risk—otherwise how the cash flow comes is unimportant.

Cash flow needs are exceedingly important to investors. Too many investors were raised with no appropriate sense of how to think about this. Hence it's a key part of client education at my firm and should be everywhere—teaching clients how to think about cash flows consistent with their needs because most haven't been taught beforehand.

Terminal value or cash flow—that's it! Typically most investors are either looking for one or the other goal, or for some combination of the two. (Although there is a very wide variety of subsets falling under these headings, such as, "I want to leave as much as I can after I die to the Save the Seals League," which means maximizing terminal value, in this case for the purpose of charity.) Sound fair? For example, an investor who is 50 may see the primary purpose of his money as taking care of him (or her) and a spouse for the rest of their lives—but they have a secondary purpose of leaving a certain amount to their offspring and more to charity. They want to maximize the likelihood of that being done successfully by maximizing their terminal value at the end of their lives. Doing so allows the cash flow they need to support their lifestyle while leaving a present for the kids and the seals. That seals it for them. Most every investor is somewhere on the scale of either needing terminal value, cash flow, or both. You must be off that spectrum to be really unique (or weird).

There is yet a third possible goal—capital preservation. True capital preservation means taking absolutely no risk to preserve the nominal value of your assets. Investors often claim they want capital preservation, but this is almost infinitely more often claimed than true. As a long-term goal it rarely makes sense. True capital preservation in the long-term is only appropriate if you know you already have much more money than you'll ever need—so you have no desire for more and your primary purpose is to minimize your worry or hassle-factor. Then it can make sense, but there are precious few such folks.

On a shorter-term basis, it makes sense if you're young and saving for the down-payment on a home in six months. It makes complete sense to preserve the cash needed for that home in a low-risk instrument such as a CD. But generally, if you bought this book, you're not stashing your cash under the mattress and have some longer-term purpose for your money. Capital preservation is the polar opposite of growth. You often hear investors hankering for—and you certainly hear marketing from firms offering up—"capital preservation and growth." Most folks who desire this would also like to get a fat-free steak. Thinking of it, I'd love one but I know it's impossible. Don't let anyone tell you the two are possible at the same time. They aren't.

Why are growth and capital preservation together a complete and total impossibility? To get growth, you must take some risk. Capital preservation is the absence of risk. The notion of combining the two implies riskless return which is impossible. Now, if your goal is growth, and 20 years from now your account has doubled three times (which isn't unlikely if you benchmark against an equity index), you have effectively grown your account and preserved your initial capital to boot. Sure, during those 20 years your account was up and down with the market, but who cares? You got growth while enduring volatility and other risks. You had a long time frame, and at the end of the day you got your equity-like return. But if your goal is really capital preservation, 20 years from now you'll still have your initial capital and nothing else.

If someone in the finance world offers you "capital preservation and growth," know they either don't know what they're doing or they're deceiving you—blissfully ignorant or ill-intended—either way dangerous. Saying "capital preservation and growth" is like saying "a selfless politician," "a mature child," or "love plus date rape." The two have nothing to do with each other. The industry loves selling capital preservation and growth. It sounds warm, comforting and fuzzy—like a cute and cuddly puppy. Who doesn't want to protect what they have and grow at the same darn time—and who doesn't love puppies? Which is why the suggestion of growth and capital preservation is insidious.

Make no mistake. Most investors need some degree of growth or they wouldn't bother with stocks, bonds, or anything involving risk in the first place. If your goal is to never lose a dime over any period—true capital preservation—you should have saved what you paid for this book and stashed it under your mattress. Of course, even if your goal is avoiding all monetary loss, the mattress stash isn't the best bet because of inflation's long-term effect. Inflation risk is the weak underbelly of those seeking capital preservation. How do you preserve capital without risk if inflation ignites? It really is hard, if not impossible, to avoid all risk.

Consider this at the very rich end. Since 1982, each Fall Forbes magazine analyzes and lists the 400 richest Americans—the Forbes 400. The individuals change a lot over the years. It isn't easy staying on that list. New people come in from below by doing really well. People on the list suffer bad fates and drop off. The bottom 50 names are in constant flux. Via the 2005 issue the poorest member of the Forbes 400 was worth $900 million.[174] There were actually 17 of them tied at that level. But in 1982—not quite two years before my Forbes column started—the poorest member, number 400, was worth $75 million.[175] Staying on the list over the ensuing 23 years required that poorest little 1982 rich boy to increase his net worth by at least 11.5 percent per year (after-tax). That's scary. Just to stay on the Forbes 400 people had to do about as well as the S&P 500 after-tax, which you know precious few people do. Only about 10 percent of the original members of the 1982 Forbes 400 are still there. That is very consistent with few professional investors beating the market. Sure, some dropped off the list by death, but many more simply couldn't achieve enough growth to keep up with their peers. It isn't easy.

How about cash flow as a goal? Since the company pension has been falling out of favor, many investors must rely on savings, whether via a 401(k) or other vehicles, to fund retirement. But how much consumable cash flow can you expect your assets to produce without running the risk of having to return to work at age 85? An imperfect, rough rule of thumb is about 4 percent of your portfolio or less. That is a gross generalization. If you have a shorter time horizon you can safely consume more—with a longer time horizon, less. But if you need $50,000 in today's dollars to maintain your lifestyle and you have a long time horizon, you should retire with at least $1,250,000 (also today's dollars). And even then it might not be enough if future returns are low and inflation is above average. Remember, there are no guarantees. Risk is ever present.

Think you may need more than 4 percent cash flow from your assets? As the percentage increases, so does the likelihood your money runs out before you do. If you don't have heirs or still haven't forgiven your kids for throwing that keg party when you were off to Europe, then depletion is a lesser worry. Let the final check bounce, as they say.

To figure out the probability your nest egg will keep supporting your lifestyle, you can do a simple Monte Carlo simulation. You can find a good Monte Carlo simulator at http://www.moneychimp.com/articles/volatility/montecarlo.htm. In general, you'll find annual distributions of 4 percent or less of your asset size improve your odds and are your best bet. Anything higher and you may find yourself sharpening your job skills in retirement instead of lowering your handicap.

So—terminal value or cash flow or both! But how do you achieve those goals? And how do you stop the failure cycle and start being right more often than wrong? Just as you don't need advanced scholarship or apprenticeship to learn to use the Questions, building a strategy is as easy as following four rules I employ every day in managing money:

- Rule Number One:

Select an appropriate benchmark.

- Rule Number Two:

Analyze the benchmark's components and assign expected risk and return.

- Rule Number Three:

Blend noncorrelated or negatively correlated securities to moderate risk relative to expected return.

- Rule Number Four:

Always remember you can be wrong, so don't stray from the first three rules.

Let's examine these four rules more closely.

You know the benchmark is vital to success. You know what a benchmark should be (well-constructed) and what it shouldn't be (priced-weighted like the Dow). As important, your benchmark should be appropriate for you. It will dictate your volatility, your return expectation, even to some extent what ends up in your portfolio—it's your road map, your measuring stick. You can't change it soon unless something really radical happens to you changing the primary purpose of your money—like your wife (or husband) and kids all die, heaven help you, also causing you to no longer feel charitable. So it's crucial you select the right benchmark for you.

Your benchmark can be all equity (as we discussed), all fixed income, or a blend of the two. Picking a benchmark—deciding if you need an all-equity, blended, or even an all fixed income benchmark—depends on four things, and only four things. Throw the nonsense "risk tolerance" baloney out the window. The only four factors for figuring which benchmark is appropriate for you are: (1) your time horizon, (2) how much cash flow you need and when, (3) your return expectations, and (4) the off chance that you have weird but strong felt views like you hate the French or don't want to own stocks that produce you-name-it—tofu—I hate that stuff.

Your time horizon may be your life expectancy but is likely longer. Unless you hate your spouse, you should consider his or her life expectancy as well. That may extend your time horizon as your spouse may outlive you. If you like your kids and want to leave something behind for them, that also extends your time horizon. Simply put, your time horizon is how long you need your assets to last. Your time horizon is decidedly not how long it is until you retire or start taking distributions. Far too many investors think exactly wrong about time horizon; they aren't using Questions One and Two to see this clearly. The industry even promotes wrongheaded thinking, likely in an effort to sell static asset allocation or other inappropriate but feel-good products.

I couldn't tell you how often I hear someone say, "I'm retiring, so I must become conservative and I can't take risk." Legions of people say that but it's usually wrong. Suppose you're a 65-year-old man and your wife is 60 and she is likely to live to 90 (very common). Then, you have a 30-year time horizon that includes a third of her whole life and you better take risk and have an equity benchmark or she is likely to suffer aged poverty. Now, if you really hate her, then aged poverty is a pretty good idea. It is, after all, more brutal in the long-term than just punching her now. I think you get my point. But I can't tell you how many times I've seen the older husband with the younger wife with a long horizon investing as if he hated his wife without realizing what he was doing because he was managing their money based on his life expectancy rather than hers. From time to time, I ask them if they hate their wives and they always get mad at me. You may have some reasonable date in mind for when you plan to start living off your assets, but the money still needs to work your whole life or beyond, or you or your loved ones will suffer. That whole period is your time horizon.

You might have a shorter time horizon, for some reason—maybe you're a 32-year-old who needs every penny to pay for that first home in three years. But in most cases, investors tend to grossly underestimate their time horizons. Because my father died at 96 and my mother is still alive at 87 and I have been both of their conservators in their agedness, it's darned easy for me to envision long time horizons. It's late in life people need their money because there are so many comforts that benefit the aged that aren't covered by any form of health insurance.

Figure 9.1 helps you think about how your time horizon relates to your benchmark. The longer your time horizon, the more equity is appropriate in your benchmark.

If your time horizon is over 15 years—and if you're reading this book it probably is—an all-equity benchmark is probably most appropriate for you. Over long time periods, stocks are by far the best performing liquid asset class and the likelihood of stocks outperforming bonds is great. Since 1926, there have been 66 15-year rolling time periods. In 61 of them (92 percent), stocks beat bonds, returning an average of 481 percent while bonds returned 150 percent.[176] That is a 3.2 to 1 out-performance. The five times bonds outperformed stocks, the margin was only 2.3 to 1.

If you have a 20-year time horizon (or more—and you probably do), the odds are stacked even more heavily in your favor if you have an all-equity benchmark. In 60 of the 61 20-year rolling time periods since 1926, stocks have outperformed bonds by still greater proportions.[177] That's over 98 percent of the time. In return for investing in stocks over a 20-year period, folks got an average return of 929 percent compared to 240 percent for bonds. During the one 20-year period (January 1, 1929 through December 31, 1948) when bonds beat stocks, bonds returned 115 percent and stocks 84 percent.[178] Big whoop! That one time period included the global Great Depression and a World War, by the way (not to mention the creation of the SEC, the emergence of Blues, and, of course, Al Capone, Gertrude Stein's one big hit, and Stalin). In the highly unlikely event that bonds outperform stocks over the next 20 years, you probably wouldn't get much more bang for your buck. It's clearly better to take on the odds and get the superior return.

You may feel as though I'm banging an equity drum. Guilty as charged. I am a big fan of stocks because of their superior longer-term returns (and lots of other reasons—recall that I pray at the altar of Capitalism's multitudinous blessings and you can't have Capitalism without stocks). However, there are times when stocks do lousy—in a bear market—and avoiding a down-a-lot world through cash holdings becomes a great tactic. But it's not a strategy.

The other time a 100 percent equity benchmark may be inappropriate has to do with the second determinant of benchmark selection—cash flow. If you need 3 percent or less each year from your assets, you probably don't need a blended benchmark and the all-equity option is probably most appropriate. An all-equity benchmark should get you the inflation-adjusted cash flow you need while still appreciating over time. Suppose you do need 4 percent each year (or even more, though I don't recommend taking that much) but you're more concerned the assets grow as much as possible over your time horizon. If so, you also should use an all-equity benchmark.

Now suppose you're drawing close to retirement or plan on taking money from your portfolio on a regular basis for some other reason. You've saved $1 million in your 401(k) and IRA and some taxable savings combined. You know that starting in three or five years, or maybe even next month, you'll want $40,000 a year to help cover your living expenses. Let's also say you don't care one whit about leaving anything to your kids or grandkids. Couldn't care less—call them "ungrateful degenerates." Your primary focus is ensuring you get your $40,000 per year, adjusted for inflation of course. Then, having some fixed income as part of your benchmark may be appropriate—maybe something like 70 percent equity and 30 percent fixed income.

Actually, I'm a bit goosey about this blended allocation approach due to the well-known "curmudgeon factor." I've seen some pretty big curmudgeons through my decades helping investors. And I doubt you're a bigger curmudgeon than I am. (It's probably obvious—I'm very opinionated and pretty independent.) In observing curmudgeons, as they age, many get a softer heart for their "ungrateful degenerates" and finally wish they had more to leave them and would have been better served had they earlier assumed a longer time horizon and a need for higher returns. Think about it.

Even with a blended benchmark—60 percent equity and 40 percent fixed income or 70 percent/30 percent or whatever—there may come a time when you should boost your cash to 100 percent to be defensive temporarily, and you shouldn't get lulled into a false sense of security with a fixed allocation. Your benchmark is your road map, but not necessarily what you own all the time. In a major bear market you'll still lose money with a rigid fixed allocation. Sometimes you need a detour. Or a dividend!

Another reason investors hit a panic button at or near retirement and plow all of their hard-earned assets into bonds and high-dividend paying stocks is they think they need the coupon payments and dividends for income. They believe if they kick off a decent percent in income, they can sit back and let the portfolio provide for retirement. As mentioned earlier, this confuses income with cash flow.

Use Question One for this myth—and it is a myth. Is it true a portfolio stacked with bonds and high-dividend stocks will provide income throughout retirement? Maybe! Maybe you're worth $10 million and want only $50,000 a year. Maybe you don't need the assets to grow so your income remains inflation-adjusted. Maybe it doesn't matter much if you see your assets diminished through reinvestment risk or if the high-dividend paying stocks tank in value.

But most folks can't afford to have their assets stagnate or decrease significantly throughout retirement. What happens when you reinvest a maturing 9 percent bond from 1997, and the only thing you can buy in 2007 that isn't risky yields 5 percent? And how about when that dandy utility stock paying an 8 percent dividend depreciates 40 percent in price? Eight percent of 40 percent less market value is probably not what you were banking on. And what about inflation?

It's simply not true coupon payments and dividends are a "safe" way to garner income from your portfolio. But how else do you get cash? If you have an all-equity benchmark and you need cash flow, you don't want to sell stock to provide cash for yourself. Do you?

I can't tell you how many investors I've heard over the decades say, "The last thing I'll ever do is use any of my principal." Why the heck not? What's it there for? This is a Question Two solution I've come up with for maintaining healthy growth while providing cash flow from portfolios, and I call them home-grown dividends.

Let's say you have a million dollar portfolio, and you take $40,000 a year in even monthly distributions of $3,333 a month—give or take. You should keep about twice that much in cash in your portfolio at all times so you don't rush to sell a nit-picky number of stocks each month. Then, you can be tactical about what you sell and when. But you're always looking to prune back, planning for distributions a month or two out. You can sell down stocks to use as a tax-loss to offset gains you might realize. You can pare back positions that are over-weighted. You'll probably always have some dividend-paying stocks to add some cash, but that is a derivative of picking the right kinds. Homegrown dividends are tax-efficient, cheap to raise, and keep you fully and appropriately invested.

The third factor in selecting an appropriate benchmark is return expectation. If you're 50 and want to retire in five years and need $500 thousand a year to maintain your lifestyle and have $2 million you're in for a caught-with-your-pants-down rude awakening. Your return expectations are gonzo high. Unless you anticipate a windfall on the order of $10 million (or so) sometime in the in-your-dreams future, plan instead on taking $80,000 a year or less and get over it. Or keep working. Start figuring out a way to explain this to your wife (or husband) now.

But imagine an investor, call her Jane, who has a reliable income source lined up for her retirement (a pension, perhaps, with some rental income). She doesn't need her assets to grow to provide for her and her husband. Jane intends to leave her money to her kids but doesn't really care about "maximizing terminal value." Instead she is nervous about volatility and looking for that "sleep-at-night" factor. I'd still recommend an all-equity benchmark and some warm milk.

Why? Because Jane has a long time horizon and needs no income. She may think she is "risk averse"—but remember, how much risk investors can handle has nothing to do with their prior feelings. As stated earlier, few investors envision their future risk orientation correctly. I'll repeat that—it has nothing to do with feelings. Many people in the industry try to make you think it does, but it's not true. A few years down the road Jane will get used to volatility.

Just because most investors have similar goals and aren't as unique as they think doesn't mean they're not peculiar. This isn't about "being uncomfortable" with foreign investing, health care stocks, tech, emerging markets, or whatever because that is more stubbornness than peculiarity. This is about having strong feelings about a particular company or a narrow sector deriving from personal belief or peculiarity. And it's okay to create a customized benchmark reflecting your own weird idiosyncrasies.

Suppose you really do hate the French so you don't want to own French stocks. Well if you do, were I you, I'd prefer to buy their assets cheaply and sell them back at higher prices later. It's about the cruelest thing you can do to those you dislike—legally with head held high. But you may feel differently about it. Some folks do. You may simply want to never, ever own a French stock. Or the stock of a firm making tobacco products. Or a firm making tofu (ugh!). Whatever! Your idiosyncrasies are up to you. It's fine to have a customized benchmark that is the World ex-France. Or the World ex-France and ex-tofu. Or whatever bizarre (or not so bizarre) moral code you sport. Since all major categories have similar long-term returns, the degree of return variation caused by those slight variances from a vastly bigger and maybe global benchmark won't be enough to count. And they'll make you feel better about what you're doing so you're more likely to keep doing it. There are no investors who have had a bad investing history having otherwise done portfolio management right because they chose to create their own customized benchmark that was the World ex-Iowa (for those of you who divorced someone from there once. Still, were I you, I'd rather get my revenge on the Iowans by buying Iowa stocks too cheap).

Whatever it is, you may have strong enough personal feelings to warrant a particular benchmark free from some offending stock or microsector. But watch if you start having feelings about whole sectors, because that might be driven more by loss aversion and hindsight bias than your own individual freakiness. Plenty of investors decided they had developed a severe allergic reaction to tech post-2002. That is a cognitive error, not a peculiarity.

So, the amount of risk you can handle has to do with (say it with me) (1) time horizon, (2) income needs, (3) return expectation, and (4) extreme individual peculiarities. Jane thinks she is risk averse now, but in 1999 considered herself aggressive and was overweight to tech stocks and now thinks she has learned. She might feel differently again—maybe aggressive about energy. Feelings can change fast—they don't mean much. What does mean much is how long your assets must last and how much cash flow you will take. And, of course, if you're morally opposed to tobacco now, you probably will be in the future too. That won't go up in smoke.

Hey, I'm not saying you must have the all-equity benchmark if it will cause (or exacerbate) ulcers. I'm just saying the cause of the ulcers may be something else. Explore it a bit.

Choose your benchmark carefully, because once selected, it's yours for a very long time, maybe the entire life of your assets. Forever and ever, Amen. Superficial benchmark shifting is a recipe for disaster. Let's call benchmark shifting what it really is—heat chasing. When someone shifts their benchmark from the Nasdaq in 1999 to the Russell 2000 Value Index in 2005, you know they were matching their benchmark to what had been hot—simple heat chasing. People chasing heat, trying to get better returns, forget about transaction costs and taxes and invariably in-and-out relatively backward—lagging the market by going into what used to work instead of what will work.

You now know all well-constructed benchmarks will get to about the same place over the very long-term. If you get the urge to switch benchmarks, check yourself and ask Question Three. Benchmark switching is the direct result of regret shunning and pride accumulation, possibly some order preference and overconfidence to boot. Don't give in. If you switch, you usually end up chasing heat and missing returns altogether. Only heartache and harm comes from it.

There are two good exceptions to this rule—only two. One is if something happens to drastically change the primary purposes of your money, including your time horizon. This is the 75 year-old in bad health from a short-lived family with a 70-year-old wife in good health from a long-lived family where the wife dies unexpectedly in a car crash. No kids, no charity, and his time horizon just collapsed. That's a good justification for switching to a benchmark more appropriate for a new shorter and sadder time horizon. Or, the other way around! Maybe late in life you remarry a younger or healthier person, extending your time horizon. It would be okay to switch to a more appropriate benchmark then, too.

The second reason to switch benchmarks, beyond a change in the fundamentals of your life, is if a future benchmark is created reflecting the same universe as your current benchmark—but the new one is somehow better constructed. This is purely tactical. Here is an example: The MSCI World Index is an excellent, broad benchmark but it doesn't include so-called emerging markets, restricting itself to developed markets. Then, MSCI created the ACWI. Same construction but broader. That should be better for the whole world.

Should you use one over the other? In my mind it isn't a big deal one way or the other and I'm prone to not switching—it's hard to argue the one is drastically superior to the other. If you're currently using the MSCI World, the time to switch would be when ACWI was older, after a period when emerging markets had done lousy for years.

The whole World versus ACWI issue is sort of like choosing either the northern 80/90 route or the southern 70/44/40 route to motor across America. Either is an okay benchmark and gets from East to West Coast just fine. But if there were a new world index—improved and drastically more reflective of the whole world stock market—that would justify switching, too. What I want you to see is it takes something pretty material to justify a benchmark switch.

The second rule of portfolio management helps determine what exactly belongs in your portfolio, how much, and when. It's a lot less complicated than it sounds. Your benchmark, particularly if you use a broad one, will be made up of different components, as discussed in Chapter 4. The Nasdaq is fairly easy—do you think tech will do well this year or not? But unless you seek an exceedingly bumpy ride, we've already established you're not using Nasdaq as your benchmark.

No matter which benchmark you pick, it's your guide for building your portfolio. If your benchmark is about 60 percent U.S. stocks, your portfolio should be about 60 percent U.S. stocks unless you've used the Questions to know something others don't. (If you have, you might at a point in time own no stocks at all.) If your benchmark is about 10 percent energy, you should be about 10 percent energy if you don't know something others don't through the Questions. (But if you think you know something others don't, you might own no energy, 5 percent energy, or be double weight at 20 percent energy because you have the basis for a bet.) Your aim is to perform similarly to your benchmark if you don't know something others don't and better than the benchmark if you do know something. Of course, the more you know that others don't, the bigger you'll make your bets and the more dissimilar you'll be to your benchmark. (If you can't recall how the heck to tell what "components" are in your benchmark, flip back to Chapter 4.)

Nervous about doing it right? Don't be. If you have less than $200 thousand or so to invest, you will probably and primarily be buying funds anyway. There are plenty of index funds that can get you the exposure you need. For example, if the S&P 500 is your benchmark, you're covered beautifully with an S&P 500 index fund. Using the MSCI World or ACWI as your benchmark? Check www.mscibarra.com for the approximate weight of the United States relative to the world (it's been fluctuating around 50/50). Buy the aforementioned S&P 500 index fund with half your dough, and an MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australia, Far East) index fund. Want to beat the market? It's harder to do if you have fewer choices to make, as you will with funds. This is why a broad benchmark with lots of components gives you more market beating opportunities. You can use your Three Questions to make foreign versus U.S. bets. And you can use other ETFs to make bets on sectors or styles without ever owning individual stocks, which is hard to do with a smaller portfolio.

If you're richer, you can and should buy individual stocks. The more money you have, the higher the proportion that should be in underlying stocks because in large volume stocks are cheaper to own than anything including mutual funds, ETFs, or any other form of equity. One benefit of stocks is they're cheap to buy and pretty much free to hold. But whether ETFs or individual stocks—start paying attention to individual sectors and subsectors now. All this information is also on the index's web page. For example, your components and their weights will look something like Table 9.1, where we have listed the percentage weights of countries and sectors in the MSCI World Index as of June 30, 2006.

You should check back periodically to ensure nothing has gotten out of whack. Don't feel compelled to rebalance if your portfolio or the benchmark has shifted a few percentage points here and there. Don't sweat the small stuff. Think about rebalancing once or twice a year unless there is a major sector or country move or you come upon something in between where suddenly you know something others don't. You'll make fewer mistakes and pay fewer fees. Trading too often is a by-product of overconfidence (thinking you have the basis for a bet when you don't).

Table 9.1. MSCI World Weights

Source: Thomson Financial Datastream, as of June 30, 2006. | |

|---|---|

SECTOR | WEIGHT |

FINANCIALS | 25.6% |

CONSUMER DISCRETIONARY | 11.2% |

INDUSTRIALS | 10.8% |

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY | 10.4% |

ENERGY | 9.9% |

HEALTH CARE | 9.6% |

CONSUMER STAPLES | 8.0% |

MATERIALS | 6.1% |

TELECOMMUNICATION SERVICES | 4.2% |

UTILITIES | 4.1% |

GRAND TOTAL | 100.0% |

COUNTRY | WEIGHT |

USA | 49.5% |

JAPAN | 11.5% |

UNITED KINGDOM | 11.3% |

FRANCE | 4.6% |

CANADA | 3.8% |

GERMANY | 3.3% |

SWITZERLAND | 3.2% |

AUSTRALIA | 2.5% |

SPAIN | 1.8% |

ITALY | 1.8% |

NETHERLANDS | 1.5% |

SWEDEN | 1.1% |

HONG KONG | 0.8% |

FINLAND | 0.7% |

BELGIUM | 0.5% |

NORWAY | 0.4% |

SINGAPORE | 0.4% |

IRELAND | 0.4% |

DENMARK | 0.3% |

GREECE | 0.3% |

AUSTRIA | 0.3% |

PORTUGAL | 0.2% |

NEW ZEALAND | 0.1% |

GRAND TOTAL | 100.0% |

With benchmark components in hand, move on to assigning expected risk and return. This too is easier than it sounds. Suppose you're using the ACWI. It's made up of 48 countries including America.[179] Which countries should perform well this year, and which should lag? Here's one way to think about it—which countries have a narrower economy prone to greater volatility fits? The United States is a very broad economy, the broadest, and likely to be less volatile than Finland whose economy is heavily impacted by the fate of Nokia, for good or bad.

The same goes for sectors. Look at the sectors and how they respond to market conditions. Here's one example. Some sectors, like technology, consumer discretionary, and financials, tend to do well in periods of economic expansions—they have elastic demand for their products. (That is, of course, a gross generalization—during 2004, 2005, and 2006 the economy expanded and technology lagged markedly. You still must know something others don't.) If times are good, are people more likely to buy flat screen TVs? Sure. Will companies spend on updating computers and other equipment they had put off during the leaner times? Sure. Will anyone rush out and buy twice as much toothpaste or heart medicine? Not unless they sprouted additional teeth or a spare aorta. Sectors with inelastic demand, like health care and consumer staples, usually do better when the economy is slowing—but again, not always. Still, you won't stop brushing your teeth or taking your heart medicine because of the economy. That is why health care is often thought of as a "defensive" sector.

The object is to beat or meet the benchmark fairly consistently while controlling risk relative to the benchmark. For each sector and country comprising the benchmark, assign expected risk and return. It's your assignment. Your call. You decide. Ultimately you're right or wrong but it's up to you to do it and no one else. You don't need some fancy formula for this—use the Three Questions to figure out what you can know others don't, and what you can safely ignore. Using your findings, rank the sectors and countries (if you invest globally) from high to low in terms of how much volatility you think they have and assume volatility is risk. Make a list, and assign a "risk" factor to each category from 1 to 10—10 being riskiest. It needn't be any more complicated than that. Then, rank which category you see doing best. For this, you don't need my staff of researchers. It's your assessment that matters, because later you'll use the rankings to blend your portfolio and lower your overall risk (see Rule 3). Table 9.2 is an example of how your list might look. Don't be influenced by our rankings—these are just dummy numbers for now from your friendly dummy book author.

Table 9.2. Rank Your Preferences

Risk | Return | Sector |

|---|---|---|

6 | 3 | Consumer Discretionary |

8 | 10 | Consumer Staples |

1 | 1 | Energy |

5 | 2 | Financials |

4 | 9 | Health Care |

9 | 8 | Industrials |

2 | 4 | Information Technology |

10 | 6 | Materials |

3 | 5 | Telecom |

7 | 7 | Utilities |

Anticipation of market conditions in specific sectors and countries allows you to weight accordingly in building your portfolio. Do your Three Questions lead you to you see some countries or sectors doing much better than others? Give them a higher return ranking—maybe a 7 or 8—so you know to take modest amounts of benchmark risk by overweighting those. Ditto for those you see doing badly—give them a lower ranking so you know to underweight there. Is there one sector you're sure you know something unique that is bullish? Give it the highest ranking so you overweight it more materially. Maybe it's a 7 percent global weight and you double it to 14 percent because you're just sure you're right, not just overconfident.

What if you can't find something others don't know, and you don't feel comfortable making a particular forecast for a country or sector? What does Yoda say? Benchmark-like, you must be. Give it a middling rank. If you haven't used the Three Questions and you know nothing others don't know, you're better off being just like the benchmark. The idea is to be right more often than wrong, not lucky and right some and unlucky and wrong more.

The purpose of this list isn't to give you a pointless exercise. The list clarifies your analysis and simplifies your decision making. You won't be constantly revisiting the thoughts behind each decision—you'll know how to weight a two versus a five versus an eight versus a ten. And with your list, you're ready for Rule Number Three.

This rule is about managing risk relative to benchmark. Most investors, even new investors, understand intuitively that diversification helps reduce risk. Remember the poor Enron employees with their 401(k)s all in Enron stock? It can be avoided through diversification. Companies go bankrupt for many reasons. Stocks implode for even more reasons. The CEOs may have done nothing wrong—just couldn't compete with fire-breathing competitors. The stock ofa perfectly healthy firm can tank for no seeming reason—with no forewarning. This is why no one stock should make up too much of your holdings.

My father was a lifelong advocate of concentrated portfolios. Warren Buf-fett has always been an advocate of concentrated portfolios. Yet I say to you the only basis for a concentrated portfolio is near infinite faith you know a lot others don't know. That won't allow for overconfidence. You must be certain you're not overconfident. If you don't really know a lot others don't know, concentrating portfolios is simply an exercise in overconfidence and increased risk. Owning less than 5 percent of one stock doesn't mean in just one account. If you have a 401(k), an IRA, and a taxable brokerage account, make sure you keep single stock ownership to less than 5 percent across all of your accounts.

You've heard the saying, "You must concentrate to get wealth, diversify to protect wealth." Those who got rich on one, two, or ten stocks are fortunate fools. Yes, with one stock you can experience thrilling upside. You can also experience crushing downside. Note the fool who gets lucky and wins this way will accumulate pride and assume he is smart. His wife and kids will know better and the more so for his success. (Of course, by this I don't mean owning one stock that is a firm you started and control. That's how Bill Gates, the world's richest man, and any number of other super rich people got their riches—they started and built a firm, nothing else, and along the way got phenomenally rich. I'm talking about being concentrated in one or a few stocks you don't control.)

As no one equity type outperforms all of the time (which you can test for yourself again using Question One), diversification helps spread risk between countries, industries, and companies. It hedges your bets against crises (such as war or oil shortages), unexpected events (earnings shortfalls, accounting scandals, or natural disasters), and combinations of the two (natural disaster induced oil shortages).

Though there are really many types of risk, standard finance theory defines risk as volatility measured by the standard deviation or variance of returns. Most investors think when the market is up it's good and when it is down it's volatile. But volatility is a dual edge sword and ever present. Your question should be: Is this category or stock more or less volatile than its peers? Diversification reduces the volatility of your overall holdings, and therefore reduces risk. Modern portfolio analysis has shown even a random mix of investments is less volatile than putting everything in a single category.

Make sure your portfolio has elements behaving differently in different market scenarios—which happens naturally if you have a broad enough benchmark and obey it. Each sector or country in your benchmark moves differently than the others. If you follow Rule Number Three and keep those sectors and countries that have low or negative correlation in your portfolio at all times, even if you suspect they won't be your portfolio MVP, you'll reduce overall volatility and improve long-term performance.

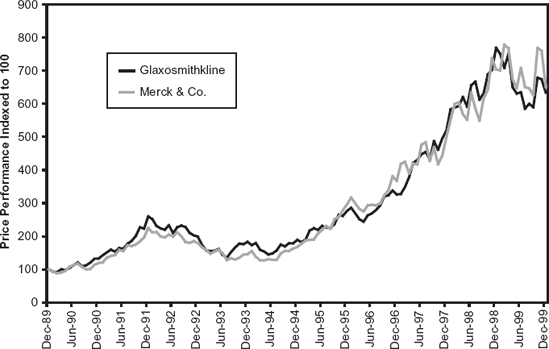

Recall our discussion about sectors with elastic versus inelastic demand—technology and health care, respectively. These two sectors are good examples since they usually have a short-term negative correlation—one is up when the other is down. Notice in Figure 9.2 that the performance of the two in 2000 is nearly a mirror image.

Rule Number Three, blending dissimilar elements, is about managing risk relative to return. The standard deviation, which is a risk measure, for each sector during the time period was 3.5 percent for tech and 2.5 percent for health care. But, if you had half your portfolio in each sector (not a good idea, but pretend for illustration's sake), your standard deviation, and therefore your volatility risk, was actually 2.0 percent.[180] You get lower risk simply by holding two differing kinds of stocks, which over this time period, had a negative correlation.

Then again, maybe you used the Three Questions to develop a strong confidence that one will best the other. By all means overweight the one and underweight the other. Your list from Rule Number Two helps you—just be sure to include all your benchmark's components and you should have a well-blended portfolio. Use that list to make decisions about how big, small, or nonexistent you want your relative over- and underweights to be. Be ruled by your rankings, which were driven by what you used the Three Questions to know. But to the degree you're not very confident, leaving the reverse-correlated position in your portfolio is like paying an insurance premium against being wrong. This doesn't just work for components with negative correlations. Any blend of dissimilar categories—whether they have negative, low, or no correlation—improves return over time while lowering risk. (Use Question One to test it out. Take any two, four, or six stocks from different categories and test over long periods.)

Rule Number Four, possibly the most important rule of the four, is about controlling your behavior. It's a way to ensure including Question Three—always. Without this rule, you are carried away by cognitive errors. Rule Four forces you to accumulate regret and shun pride. With Rule Four, you reduce the risk of being overconfident. Anytime you're tempted to disregard the first three rules and make a decision not based on the Three Questions but on some herd-mentality or Stone-Age inclination, Rule Four keeps you in line. With every decision you make—regardless of how confident you are, you can always be wrong. Once you accept that, you're less likely to do something too crippling.

Rule Four forces you to use your benchmark like a leash for a puppy in training. With a short leash, your pup can't get in too much trouble. The same dog on a long leash can dig up a garden, run into a pit bull, get hit by a car, or chase a stray cat across town.

For example, suppose you're confident tech will do well this year. Tech is 15 percent of your benchmark. But you're not satisfied with overweighting it to 20 percent or even 25 percent. You KNOW tech will be tops. Your confidence tempts you to jettison all your health care stocks for an even larger tech allocation because you know health care typically lags when tech is hot. Before changing your portfolio, ask yourself, "What if I am wrong?" Are you prepared for the consequences of such a big bet?

This rule is the primary reason I manage money with a core strategy and a counter strategy. The core strategies are market bets I make—relative benchmark overweights—based on what I believe I know that others don't. For example, if I believe America will outperform foreign, tech will outperform health care, consumer discretionary will outperform consumer staples, I make overweights relative to the benchmark in those areas. Those are my core strategies.

In my underweight sectors, I build my planned counter strategies. These are areas I don't expect to do well. I have them there because—what if I am wrong? Hey—I'm wrong a lot. I've been fortunate to be right more often than wrong in my career, but I know I've been wrong and will definitely be wrong again and plenty of times. Each of the counter strategies are areas I expect to do well in the event one of my core strategies fails and does badly. If I'm wrong about tech, health care will likely be a better performing sector. Either American or foreign stocks will be the lead pony, so I don't want to miss out if I'm wrong about that. I always ask myself, "What will do really well if what I think will do well actually does badly for some reason I can't foresee?" I want some of that too. Most investors never think this way.

Having a counter strategy means you'll always have "down" or "laggard" stocks. If you're really right like you expect, your counter strategy stocks should be down or lagging. If counter strategy stocks are down, it means your core strategies are kicking into high gear and you're doing great overall on a portfolio level. Counter strategy stocks being down isn't bad. They keep you from getting killed when you're wrong. That's managing risk which is good. One thing about my career I'm pleased with is when I've been wrong and lagged I haven't lagged by a lot. And I haven't lagged by a lot because I've built in the counter strategies.

Here's a practical example of core and counter strategies, again using tech and health care for consistency. Pretend you're benchmark neutral on every sector but tech and health care. You're new to this Three Questions thing, so you focus on just health care to start. You believe you've uncovered something no one else is seeing which should make health care super hot. Maybe you discovered every member of Congress hit their heads over the weekend (I'd vote for that). You also know the congressmen (and women) have a vote pending Tuesday on drug regulation. They want their new pain relief medicine, and fast, so they'll do something contrary to their nature—reduce governmental control. As such, you believe the FDA will begin green-lighting a whole slew of insanely efficacious drugs. (I said we were pretending.) No one else sees this. Everyone else thinks congressmen with headaches are bearish because they believe it will make them groggy and stupid. But you know better! You know they were already idiots.

Based on your unique view you decide to overweight health care. When you used Rule Number Two, you assigned health care an expected return ranking of 8, so you decide to increase your health care holdings to 15 percent from a benchmark weight of 10 percent. That is a 50 percent overweight and constitutes your core strategy.

Now, unless you're using margin, your assets must add up to 100 percent, not 105 percent, so you must reduce your holdings elsewhere by 5 percent. Where? Suppose tech is also 12 percent of your benchmark. If drug stocks do badly your full 12 percent tech weight will soften the blow. But if you're very confident about your drug play, you'll take the whole 5 percent out of tech, decreasing your tech weight from 12 percent to 7 percent and increasing the real size of your bet by minimizing how much counter strategy you have. You still have a 7 percent weight, but it is a smaller counter strategy than if you took the 5 percent haircut from elsewhere.

Thinking it through with the Questions, you discover most folks agree tech is undervalued because tech P/Es are low. Also, the dollar has been strong recently (for argument's sake) and folks expect that to continue and from that they think U.S. stocks will be strong. Everyone remembers the 1990s when America led and so did tech.

But you know low P/Es aren't automatically low-risk, high-return. You know a strong dollar last year doesn't mean a strong dollar this year. You know a strong dollar doesn't make American stocks beat foreign. Noting the near-universal bullishness on tech you conclude you really won't need a full counter strategy and decide to underweight tech by 5 percent—putting your weight at 7 percent. Still you have a counter strategy that helps if your core drug strategy fails. If you're right about health care, you'll probably (but not necessarily) also be right about tech, and you'll have participated more in a hot sector and less in a lame one. You beat the market, just from getting one core and one counter strategy right (in this case by betting big and minimizing your counter strategy).

Now you could have been more extreme. You could have moved your drug weight from 10 percent to 22 percent and your tech weight from 12 percent to 0 percent. And if it worked, you would have won huge. But you didn't. You kept that 7 percent in tech.

Suppose you're wrong about your head injury theory. Congress convenes with nothing more than a few mild head aches. The poli-tics ban all pharmaceuticals except aspirin. No one expected that, so health care tanks, and folks flock to a "hotter" sector, like tech. Two sector bets wrong. You've participated less in the hot sector and more in the lame one. Ugh! You lag benchmark. But not by much, because you didn't go nil in the hot sector and you didn't grossly overweight the laggard. It's never all that bad to lag the benchmark by a few percentage points in a single year—maybe you do 16 percent or 17 percent when the benchmark does 20 percent. After all—this isn't a game where slight differences in one year's performance count all that much. If you lag by a little for a few years you can always make that up (the operative words being "lag by a little"). You have the rest of your life to be more right than wrong.

In a year when more of your core strategies are right, you meet or beat your benchmark. There have been up-years when I've been wrong about most of my core strategies, but because I got the big decision right—the decision to hold stocks instead of cash or bonds—I lagged my benchmark but not too badly and not by an amount I can't make up later. Why? Because I never aim to beat by more than I am comfortable lagging. The counter strategies save you from lagging too much in years you're wrong.

The only time I am ever comfortable beating the benchmark by a lot—taking on massive amounts of benchmark risk—is when I believe down-a-lot is by far the likeliest scenario. Then, I will try beating the benchmark by a lot to avoid the bulk of a bear market. It's the riskiest thing I ever do for clients, but over long time periods, if you beat the benchmark modestly on average, and beat the occasional bear market by a lot, you put serious spread on TGH. It's the only time I want to embrace huge benchmark risk.

That heading was there to fool you. I hope it worked! I don't know how to pick stocks that only rise. Many claim to. No one does. I've never seen anyone do it. Your goals in stock selection are two things and only these two. First, find stocks that are good representations of the categories you're trying to capture, and second, stocks you think will most likely do better than those categories. Note I didn't say, "Find stocks that will go up the most." I said, "Most likely do better than the category." Your goal is to get the attributes of the category plus a little, with "most likely" as your goal.

In building your portfolio, make sure you spend most of your time deploying the Three Questions for the most important decisions and don't get distracted by the least important decision—the individual selection of stocks. The stock selection, amazingly, has the least impact on how your portfolio performs. You may find that shocking and downright sacrilegious. Maybe you bought this book hoping to get an edge in picking stocks, and here I have spent several hundred pages talking about anything but how to pick stocks. There are several reasons—first, it just doesn't matter that much. Volumes of scholarly research have been written and there is general consensus among academics that most of your return is driven not by stock selection, but asset allocation—the decision to hold stocks, bonds, or cash in any given year, and what types. Scholars quibble about how much that most translates into. Some studies have shown more than 90 percent of return comes from asset allocations. Others say less. I won't quibble. "Most" is okay.

My research says about 70 percent of return in the long-term comes from asset allocation (stocks, bonds, or cash), and about 20 percent comes from subasset allocation—those decisions regarding types of stocks to own—whether to overweight or underweight (or be benchmark-like) on foreign or domestic, value or growth, size, sectors, and so on. But few finance academics would disagree that stock selection itself generates a small piece of your total portfolio return—it's a secondary or tertiary matter.

Think about it this way—in the late 1990s, if you used a dart to pick 30 large-cap growth stocks, you did pretty well. It didn't matter much whether you picked Merck over GlaxoSmithKline—they were large-cap growth pharmaceutical stocks that behaved similarly. Investors spent time hand-wringing and analyzing Merck's pipeline and Glaxo's earnings and this one's balance sheet and that one's 90-day moving average, but the effort had little additional benefit.

Whether Merck or Glaxo, they did pretty much the same during the 1990s, up 552 percent and 534 percent, respectively. How could you have used the Three Questions to figure out something others didn't know about Merck or Glaxo? Wouldn't it have been easier to figure out something about health care as a whole? Or large-cap stocks? Or growth stocks? Or the United States versus the United Kingdom? Had you done that, heck, you might have decided to hold both these stocks—a perfectly fine outcome (see Figure 9.3).

Fast forward to 2000 through 2002. During these years, the best decision was to be defensive and hold largely cash and bonds. If you couldn't do that, then it was small-cap value stocks. If you did that you did okay. If you did stock picking in any other part of the market you did badly. It was the decision whether to own stocks or even the type that determined return, not stock picking.

People believe in stock picking. Stock pickers are heroes. Any number of mutual fund commercials feature analysts looking thoughtful, wearing hard hats and grasping clipboards whilst inspecting airplanes or telephone poles or some such nonsense. If you wonder what the heck those suits are doing in midst a heavy machinery plant, you're on the right track. Don't get me wrong, stock selection is important. Picking the right stocks definitely adds value over time, otherwise I'd recommend everyone—even if you have vast sums to invest—to suck up the management fees and buy index funds or ETFs. And like all other investing decisions, you needn't pick the best performing stocks of all time, you just need to be right more often then wrong and let the benchmark do its work.

So where do you want to spend the majority of your investment time? On the decision that drives 70 percent or even 90 percent of your return, or on the decision that is responsible for about 10 percent of your return? (That's a rhetorical question.)

Okay! I already did that once. It was my first book Super Stocks. I don't and wouldn't do it now the way I did it then, but what I did back then wasn't bad. It was fairly state-of-the-art then. Come to think of it, there is pretty much nothing I do now like I did 25 years ago—I'd be pretty embarrassed if there were. I sure hope I know things 10 years from now that cause me to change what I'm doing now. At this point in evolution, change is the name of the game and my goal is to keep developing new things and changing. So how would I do it now?

Here's how. It's a process of elimination.

Imagine the portfolio construction process as a funnel, like the one in Figure 9.4. Into this funnel, you pour the whole world's securities—stocks, bonds, cash, the whole gamut. The only securities that drop to the bottom are those that pass a screen at each level.

Use the Three Questions to determine if you want to hold stocks this year, or get defensive. Examine the three drivers—economic, political, and sentiment—to determine which market condition is most likely. In the highly likely situation you determine the market will be one of the first three scenarios (up-a-lot, up-a-little, or down-a-little), your job is easy—you belong fully exposed to equities as dictated by your benchmark. The entire world's stocks drop through the screen to the next level.

Now you have subasset allocation screens. Use the Three Questions to decide how to relatively weight countries and sectors compared to your benchmark. (Been there done that—earlier in this book.) Here you screen stocks based on your core and counter strategies—what you want to overweight and underweight. In this midsection of the funnel, you determine percentage portfolio weights without thinking of a single stock name. Use some of what we've demonstrated in this book. At the end of your scientific inquiry, you'll have a simple list of countries, sectors, and their appropriate percentages. Stocks drop through the next screen into a bucket based on your subasset allocation decisions, and only then are you ready for individual stock selection.

Take each category, one at a time. Attacking stock selection this way is much easier and clearer. Instead of wading through the stock world, you're looking only at stocks falling in each of the specific categories you need. You're not looking at 15,000 stocks, hoping to find a handful of good ones; you're looking through 15 or 20 names per category to pick three or four stocks.

Say your higher level decisions lead you to needing a certain percentage of U.S. small-cap value industrials. You need a few decent ones—as a group likely to do as well or better than the category overall. The idea is to find stocks priced relatively cheaply compared to peers. More importantly, you want to look for a story that, should it catch on, will drive returns. I'm not talking about what you read in the front page of the Wall Street Journal, I'm talking about what you can use the Three Questions to unearth.

Here's an example. As 2005 started, I expected U.S. small-cap value industrials to continue doing well. A stock I wrote about in Forbes at the beginning of 2005 was Flowserve (FLS).[183]

By the way, I generally don't write in Forbes about stocks I select for my client portfolios. I'm not being secretive about my strategy; I just don't want to turn my clients into criminals. And I won't become one myself. If my clients were holding stocks I write about in Forbes, they could be accused of front-running, or I could be accused of doing it for them for pay. It would work like this. I buy for my clients, then recommend it in Forbes strongly, getting Forbes readers to buy it, pushing it up, and then I sell it for my clients, taking the profit. That would be criminal—a form of insider trading, a felony. I hate felonies. Always have! I've got a lifelong philosophy that says, "No felonies." To keep well out of the gray area and on the spic-and-span side of the law, I write about stocks that—for whatever reason—are perfectly grand but I don't use for client portfolios. Because (as cited earlier herein) stock picking is only a small percentage of portfolio return, I can pick different individual stocks for Forbes and my clients and have both places work out just fine, thank you. There are plenty for everyone. More than enough for what we need to do for clients and for Forbes without getting the two groups entangled in a potentially sticky way. I'll occasionally remind my readers of that in the interest of full disclosure.

Anyway, back to Flowserve. It manufactures pumps and valves for difficult liquids (corrosive ones, for example) in the chemical, petroleum, and food-processing industries (and how sexy can that be). Exciting right? I mean, don't you get up each day and think about pumps and valves for corrosive liquids? And how to capitalize on companies doing a spiffy job at valving and pumping? (There is a movie in here somewhere.) You don't find stocks like this from looking for a needle in a valve-stack. You find them by winnowing down categories.

Why Flowserve? Why not Kennametal or Idex Corp? Also great U.S. small-cap value industrial machinery stocks. Nothing wrong with them. But this was what I could fathom about Flowserve I felt no one else had. At the onset of 2005, investors were still hypersensitive about accounting "irregularities." In late 2004, Flowserve announced a new CFO, which can be fairly suspicious. A few days later, the Chief Accounting Officer resigned and just a few days after that reversed his decision. Next thing you knew, they were delaying their third-quarter SEC 10-Q filing. It was all fishy, and the stock behaved erratically in response. If you were a fundamental investor, this one would have scared you away because their balance sheet wasn't impressive. Even the price, at 26 times trailing earnings, seemed not so cheap.

All reasons most investors would stay away. Everybody knows fishy accounting coupled with an "overpriced" stock spells trouble. But it was cheap. The stock sold at 60 percent of annual revenue. There was potential for nice gains if their profit margins improved to a normal manufacturer level. Any positive news about this firm would be pleasant upside surprise. It was priced for no good news. It was priced with the expectation of more bad news and further decline. Therefore, any good news would be bullish and in a category that should do well, it should do well relative to its category—which is the goal.

Using Question Three, I made sure I wasn't being carried away by overconfidence or any other cognitive errors. I asked myself—what if I'm wrong? Suppose the stock failed to deliver? If that were the case, I would expect it to bounce around somewhere with its peers, maybe doing not quite as well. Because I expected the category to do pretty well, I thought I wouldn't be too disappointed by a laggard that everyone expected to be a laggard.

Note I didn't fly out to Flowserve's Texas headquarters and wander around their plant in a hard hat gleaning hat tricks. I never met the CEO. I didn't hire a mole to infiltrate upper management to find out something others didn't know (which is illegal along with being ridiculous—but would make a great Bruce Willis corporate spy movie). I read what was publicly available—the same information you easily find. Then I did what I always do when I'm looking at individual stocks. I ask myself, "What is everyone else worried about?" And I toss that aside. Then I ask myself, "What can I read between the lines? What kooky thing could happen to surprise to the upside or downside? How likely is that kooky thing to happen?" Finally, like Homer Simpson, I say, "All right brain, you don't like me, and I don't like you," and I figure out how my hardwiring, biases, and ego might lead me to make a poor decision about the stock. That's it. That is how you pick stocks that always win. Just kidding. That is how you pick stocks that, more often than not, are better than their peers.

If you had read Forbes and bought Flowserve at my recommendation, you would've been pretty happy. In 2005, the stock returned 44 percent.[184] compared to 2 percent for its sector,[185] 5 percent for the S&P, and 9 percent for the global broad market.[186] Flowserve was a great stock pick—it did better than its category. Was it the best performing U.S. small-cap industrial machinery stock? No. You might have happened upon JLG Industries Inc. or Joy Global Inc., returning 133 percent and 109 percent, respectively.[187] Either would have made it through the top-down selection process as well. Those two stocks might have fallen out of your funnel instead of Flowserve (or heck, you might have decided to hold all three). But what would have made you select those? You needed to see something others could not which is easier to do when looking at a small pool of stocks at the bottom of your funnel, rather than an ocean at the top. Making the right big decisions first increases the likelihood of picking better stocks like Flowserve, JLG Industries, or Joy Global from the categories you need. If you're spending hours trolling web sites and CNBC to study some German small-cap value utility stock without first considering if you even want to hold stocks or what types this year, you're wasting time and brainpower.