CHAPTER 5 LEARNING TO SEE IN THREE DIMENSIONS

Whether you’re drawing objects you observe or objects from your imagination, the ability to see the world in three dimensions is an essential tool in your artistic skillset. Yes, we all perceive depth and scale instinctively (otherwise we’d be stumbling, bumping, and dropping our way through the day), but as artists we need to turn a more critical eye to how things look in the world around us.

So much can be learned about seeing the world in three dimensions simply by paying attention. In real life, objects are more than just the simple shapes or silhouettes of a 2D drawing. Objects have dimensions in three directions that are orthogonal to each other: length, height, and width. Those same three directions (represented by the x, y, and z axes in mathematics) can describe the relative positions of objects in a space. Because of this, depth and scale are observable characteristics of three-dimensional space and the objects found within that space. Honing your observational skills can help you make the leap into giving objects from your imagination a three-dimensional appearance in your drawings.

Some of the simplest 3D objects—the cube, cone, sphere, cylinder, pyramid, and torus—are called primitives or reference objects. In various combinations, these primitives form the basis of more complex objects in the three-dimensional world we live in. Learning to see the simple objects within the complex will help you build your observational skills—and your perspective drawings.

Observing the World Around You

You can learn much by taking a moment to observe objects in the environment around you, as well as the environment itself. Suppose, for example, you’re standing in the middle of a street. The buildings, people, cars, and trees you see seem to diminish in size, presence, and even color saturation as they are located further away from you, the observer. The progression of scale as objects recede into the distance is a consistent characteristic of observed three-dimensional space and perspective. Remember this detail: One of the most effective ways to communicate depth in a drawing is the progressive reduction in size and detail of objects relative in distance to the viewer.

Your view from the middle of the street is an example of one-point perspective. One-point perspective is the view in which there seems to be one point to which all objects scale, diminish, or vanish. Another name for this conceptual point off in the distance is the vanishing point. One-point perspective has one vanishing point along the horizon line. The horizon is where everything visible diminishes in size and seems to taper off to being effectively out of sight and indistinguishable from the sky or the Earth itself.

Standing in the middle of a road is not the only way (nor, perhaps, the safest) to observe perspective at work in the world around you. A simple object like a box will show the effects of perspective at a glance if you observe carefully.

Notice that the edges of the box, although parallel and an equal distance apart in real life, appear to get closer together on the long side of the box, just like in the road scene. (Chapter 6, “Drawing with Depth in 3D,” will explain the two-point or three-point perspective theories behind why this happens.)

Edges appear to converge when an object is viewed in perspective.

The visual effect of tapering edges and reduced size at a distance is even more noticeable with larger box-like objects. Look for examples in your own immediate area, such as a table, and observe the change in apparent scale of lines and edges closest to you, as compared to lines and edges further away from you. A building or structure outside will show tapering sides much more prominently, because of the relative scale of the structure to you, the viewer.

Curvilinear shapes, such as tubes, are also a good means of observing perspective in action. Perspective affects how you perceive the relative sizes of the ends of the tube and how the shapes appear long with a general tapering along the length of the tube toward the end that is farthest away. When viewed dead-on, the end of the tube will appear circular. Change the angle relative to your eye, and the end of the tube will now appear oval. These oval shapes in perspective are called ellipses. Simply put, ellipses and ovals are circles viewed at an angle in perspective or three-dimensional space.

Ellipses are a somewhat tricky to understand but important part of drawing correct perspective of objects. Take some time to make observations about what you see related to how a cylindrical object—a straw, a Pringles can, your coffee mug—is placed relative to your eyes. View the cylindrical object from a variety of points of view and see how the object changes in appearance.

Can viewed at varying points of view. Ellipses are narrow or wide depending on view.

As objects in three-dimensional space recede into the distance, you can make a few other observations about their appearance and placement. The keys to look for are color and detail, relative scale, point of view, and contrast.

Color and Detail

As mentioned in chapter 4, the further away an object is from you, the less intense and saturated its colors will seem. This is due to atmospheric diffusion: As light is dispersed in the atmosphere, color becomes fuzzier and more desaturated. Combined with the focal length of your eyes’ lenses, atmospheric diffusion also is why you cannot see minute details of faraway objects. In a three-dimensional view, objects viewed at distance will show less detail than objects viewed up close. Distant objects mainly appear as silhouettes and shapes, although associations from your memory may help you fill in such unobservable details as texture, pattern, or distinct parts. We’ll discuss color and atmospheric perspective a bit more in Chapter 9, “Color.”

Notice the color fade off as objects recede to the horizon.

Relative Scale

Relative scale is another way we observe perspective in real life. Relative scale is how we create associations by comparison in scale and placement of the object in reference to another object in view. Consider, for example, these sketched primitive boxes.

If you cover all but one of the boxes with your hands, there is no way to tell how big the remaining box is compared to anything else. Without another object nearby, the box could be as large as a house or as small as a game die. Adding an object that is relatable and familiar may help the viewer interpret what size the box actually is. A simple silhouette of a human is a great way to show relative scale. What other objects might be familiar and useful in creating a sense of scale while drawing?

Point of View

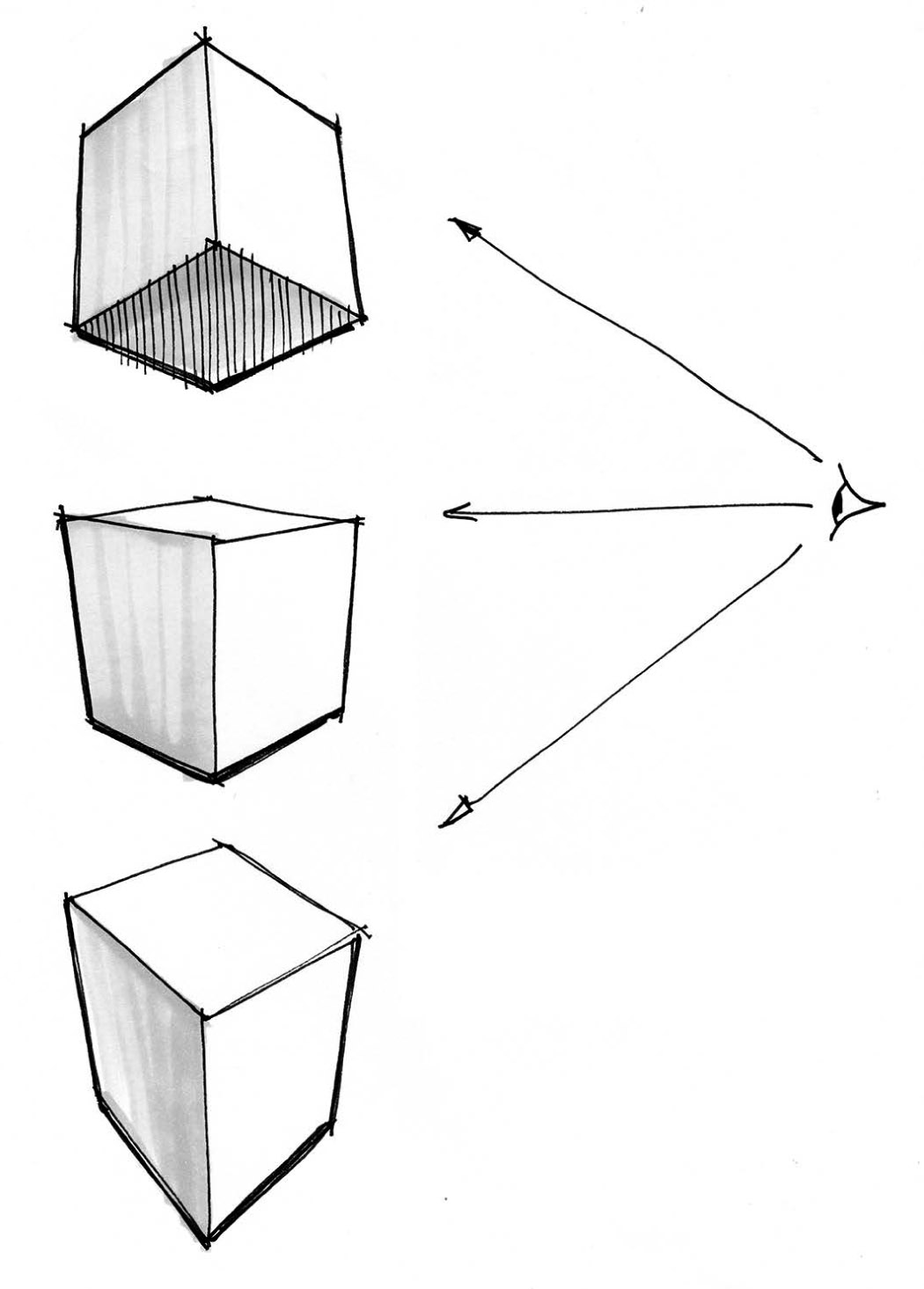

Point of view refers to the relative position of you, the observer, to the object or scene. If an object is below your eye level, you will see more of the top of the object. If the object is above you relative to your eye level, you will see more of the bottom of the object. Point of view can also be used to suggest scale in a less definitive, yet relatable way. Something that is above you tends to be perceived as large, and objects that are located and viewed below eye level tend to be perceived as being smaller. An object at eye level also has a distinct and relatable scale that is implicit in its placement. For example, a building may be at eye level and rise a bit above eye level while receding and tapering toward its respective vanishing points.

Point of view changes how an object is seen and drawn in perspective.

Contrast

Visual contrast and changes in value are other clues you can observe to learn about 3D perspective. Whenever a surface changes direction, you will see a difference in the value or tone of the surface. While sitting in a room, look at the walls around you. Visually follow one wall to its closest corner. You will likely notice that there is a difference in value between the walls as they change direction. This is due to the relative position of the walls to the light source in the room, whether it be a window, lamps, or overhead light. What observations do you notice in your environment with space, depth, and contrast?

Rounded objects behave similarly. As a cylinder or sphere curves in form and, therefore, changes direction relative to the light in the environment, it will have a core shadow along its surface. The theory behind this effect is mathematically involved and somewhat complex, so for now, just pay close attention to the way light helps you see the three dimensionality of objects in your environment.

The intensity of contrast is not as important as noticing that there is a difference in value. Value changes give us a sense of the relative space and placement of objects in your environment. Value at times may also give a sense of depth relative to where you may be in relation to the object in view. We will discuss contrast further when diving a bit deeper into light, shadow, and reflections and how these elements communicate three-dimensional forms. (See Chapter 7, “Light and Shadow”)

Draw from Observation to Draw from Imagination

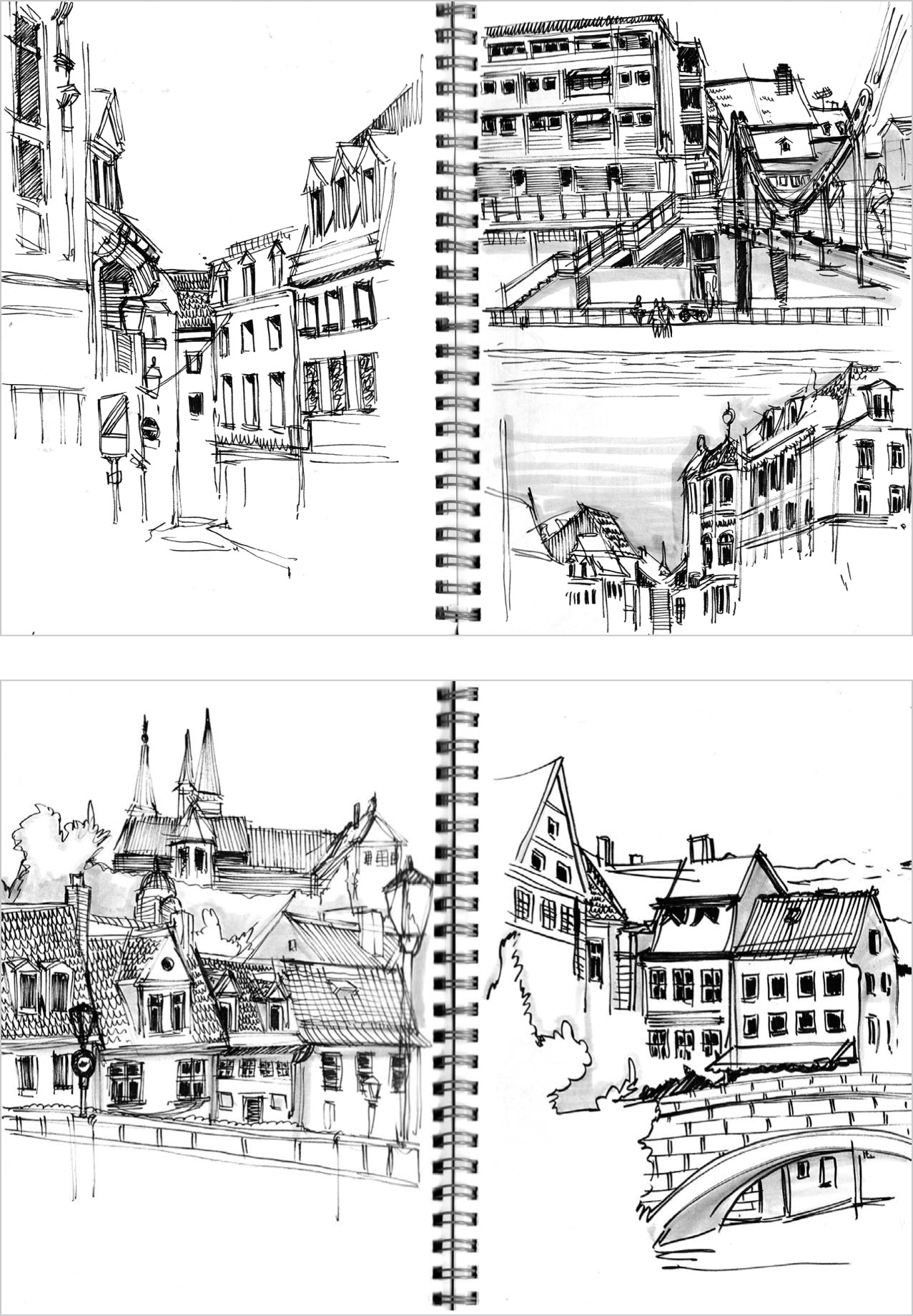

One of the most effective ways to observe reality and solidify your understanding of three-dimensional space is by drawing from observation. Drawing from observation means looking at an object or scene in real life and interpreting what you see in a two-dimensional medium such as pen, pencil, and paper. When I left corporate employment, I decided to take some time to focus on drawing from observation. I would go to my local coffee shop and draw everything I could see that was interesting and even pushed myself to try different subject matter, as well. The experience was a fantastic exercise in speed, depth perception, and translation from reality to what I could capture in a brief timeframe.

By drawing from observation, you learn to capture what you see with the tools you may have. Although there are means of measuring proportion when drawing from observation, the exercise is less about precision and more about perception for me. Observing and drawing how one object stacks up to another when considering the progression of scale in a room, for example, requires you to compare placement and details about each object to establish their relative scale and visual presence on paper. Observational drawing will help you build a visual vocabulary of symbolic ways to represent reality that you can draw from when sketching objects in imagined settings. Much like with language, we must practice and learn the vocabulary of drawing by observing and connecting concepts mentally.

Practice drawing from observation wherever you go.

While commuting to work by public transit in San Francisco, I wanted to make the best use of my travel time. Armed with my sketchbook and a pen, I would draw people on the train from observation as well as dipping into imagined objects and enhancements to the people in view. Drawing from my imagination became much easier the more I practiced this way, as I was able to pull from an established visual vocabulary of objects and scenarios that I had previously drawn from reality.

Likewise, drawing from photo references can be a convenient and appealing avenue for practice—if you know the difference between the reality captured by photography and reality itself. Lenses that have different focal lengths than the human eye may capture photos with distortions that skew or flatten the three-dimensional appearance of real objects. Spotting these distortions takes a keen eye and a familiarity with such differences as how much the linear sides of an object may taper at various focal lengths. Drawing is about communication. If you want to communicate objects in a natural-looking perspective, it’s important you learn to see things as they are in real life.

Find Inspiration in Other Artists’ Work

I’m glad you’re reading this book! Finding inspiration in the work of other artists, illustrators, or designers and watching their approach to drawing objects in perspective and three dimensions is a fantastic way to learn techniques for tackling tough perspective problems.

I spent a long time avoiding using other artists’ work as a means of learning and looking back I realize that was very stubborn on my part. At the time, I had concerns about being authentic to my own self as an artist and not wanting to “copy” the work of others. The truth is no matter how much you try, even when mimicking the work of another artist, the result will be yours. Your perspective, point of view, and approach to drawing will make the work your own. Of course, if referencing the work of another artist, illustrator, or designer, be sure to give credit where credit is due!

You can learn much from those who have gone before and done the work to figure out perspective drawing, and you may find new or interesting techniques that work for you, too.