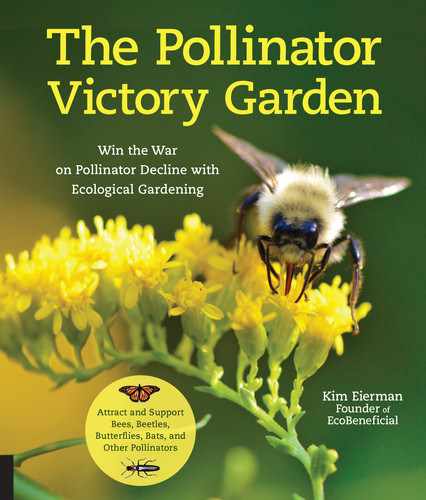

5 Creating and Growing a Pollinator Victory Garden

Now that you know the types of pollinators you can expect to see, the types of habitat to provide, and the types of forage to offer, it’s time to start creating your Pollinator Victory Garden.

A Pollinator Victory Garden can take many forms. The size and conditions of your landscape, your available time, and your budget will be the major factors determining the type of garden you create. If you have an existing flower garden, you might start simply by tweaking that space to include more pollinator plants and nesting habitat. But if you want to really devote your landscape to supporting pollinators, more detailed updates may be in order.

Site Assessment, Planning, and Planting Goals

The first order of business for any gardener is to conduct a site assessment that examines the various aspects of your landscape—before you buy any plants. This important process gives you the information you need to create a thriving garden instead of a struggling one. Bonus: much of this can be done in the off season. Here’s how.

Pollinator shade garden

Site Assessment Steps

• Define the landscape and the areas to be planted.

• Sketch the landscape and planting areas, including dimensions.

• Note general topography: slopes, low areas, etc.

• Note any obstructions at soil level, overhead, and belowground.

• Determine how many hours of full sun any potential planting area gets in the growing season. One way to do this is to photograph the site at various times of the day (morning, noon, and late afternoon). Remember that sun levels differ depending on the season.

• Identify your hardiness and heat zones (online).

• Note any sheltered areas that are warmer than others (microclimates).

• Identify any areas that are extremely windy.

• Submit a soil test to a testing lab, like your local Cooperative Extension Service, to determine soil characteristics.

• Perform a drainage test and/or identify any areas that puddle for more than twenty-four hours.

• Inventory existing plants, including perennials, trees, shrubs, and vines.

• Determine if any invasive species are present that should be removed.

Questions to Ask During the Planning Process

While you are assessing your landscape, consider these questions:

• Are there existing planted areas where you could add pollinator plants?

• What areas of lawn would you consider replacing with pollinator plant beds?

• Are there hard-to-reach areas, like hillsides, that could be planted for pollinators?

• At what times during the growing season does your landscape lack flowers?

• What other areas can you dedicate for pollinator habitat that include areas of bare soil in full sun, areas with fallen logs, brush piles, and/or dead trees?

Plant perennials in groups to give pollinators easy-to-find floral targets.

Basic Planting Goals for a Pollinator Garden

Despite the intricacies of plants and pollinators, the basic goals for pollinator gardening are pretty simple. A robust Pollinator Victory Garden offers the following:

• flowering trees, shrubs, and perennials in bloom throughout the growing season

• an emphasis on regional/local native plants, suited to your landscape conditions

• at least three species of flowering plants in bloom at the same time throughout the growing season

• a diversity of flower colors, shapes, and sizes for each time of bloom during the growing season

• a wide array of larval host plants (at least ten) for butterflies that are common in your area

• groupings of the same plant species in patches 3 feet (0.28 m) square or larger and repeated in the landscape assuming there’s sufficient room

• in meadowlike gardens, the same flowers repeated throughout the area, incorporating a diverse array of perennials

• safe, accessible habitat for a range of pollinators

• a pesticide-free landscape

• a pollinator habitat sign

Don’t feel bad if you can’t achieve all of these goals, especially in small gardens and urban landscapes. Any pollinator plants are better than none! Work with what you have; pollinators will benefit from your efforts.

Pollinator Victory Garden Projects

Getting started with pollinator gardening can be intimidating. It can be hard to decide where to plant, what to plant, how much to plant, and so forth. If a planting project is overwhelming, even the most avid gardeners, regardless of their good intentions, may simply put it off.

Planting pollinator islands

One solution is to start with a small project that can easily be envisioned, planted, and appreciated within a reasonable time frame. Here are some Pollinator Victory Garden project ideas that are achievable and will attract an abundance of pollinators to your landscape.

Pollinator Islands

Imagine creating a pollinator haven in the middle of a pollinator wasteland! Pollinator islands are a great way to support pollinators while reducing the amount of lawn (“green desert”) on your property. Since removing and replacing a lawn can be tedious, begin with a small area that seems manageable.

Consider under-used pollinator plants, such as prickly pear cactus (Opuntia humifusa) for hot, dry pollinator islands.

Find the perfect location

Select a location for your first pollinator island that you can easily see. Once the pollinators appear, you will likely be inspired to create even more pollinator islands. Consider a location in the front yard, which may help to inspire neighbors, passersby, and even the mail carrier to try pollinator gardening at their own homes.

Define the area to be planted

Make the pollinator island large enough to contain a diversity of plants, making sure to leave enough room to have a quantity of each species. Grouping each species together will provide a more traditional look and create better pollinator targets.

An irregular shape with serpentine curves is always pleasing to the eye and resonates with onlookers as it feels like an intentional garden. Since the best practice for any ecological garden is to leave perennials standing through winter to provide habitat for insects and seeds for wildlife, the neat delineation of a pollinator island serves as a “cue to care” and helps offset the presumed untidiness of dead perennials in winter.

The easiest way to create the shape of the island, or any new planting bed, is to use temporary chalk paint spray to mark the area. If you decide to change the shape, spray again; the remaining chalk will wash away.

Decide what to plant, where

Before picking up a trowel, research the expected mature size of each pollinator-friendly plant you will be planting. Young plants, especially perennial plant plugs and young woody plants, can look deceptively petite. Don’t be fooled. That 1 foot (0.3 m)-tall serviceberry may turn into a 20 foot (6 m)-tall tree. Always plant for mature size so you don’t have to move plants, prune plants, or give plants away that no longer fit in your landscape.

Pollinator islands don’t have to be large to attract pollinators.

View the potential island space from different angles to see how best to position plants. If the island is visible from all sides, the tallest plants often look best positioned in the middle. Not all plants must be flowering perennials; consider using flowering shrubs as focal points and to add structure while providing a large quantity of blooms to pollinators. If the island is obscured on one or more sides, use taller plants in the back for a pleasing design. As with most gardens, except for true meadows, tall plants usually go in back, medium-size plants are placed in the middle, and shorter plants are placed in the front. Those varied layers not only appeal to humans but also add more ecological function to our gardens.

Enhanced Foundation Plantings and Enriched Edges

Expanding or enhancing existing plantings is another simple way to improve your landscape for pollinators. Many traditional landscapes lack the right plants and the layers of plants that benefit pollinators and other wildlife. Enhanced foundation plantings and enriched landscape edges are easy ways to get started.

Enhanced foundation planting

Revamp foundation plantings

Most homes and even many commercial buildings have foundation plantings, typically a tight green curtain of some run-of-the-mill plants that hide a building’s foundation. In most cases, foundation plantings are not very useful to pollinators. That’s a lost opportunity, especially for smaller landscapes. Think outside of the box when it comes to foundation plants; they can be much more than green curtains hiding the base of a building.

Assess the available space.

Take a look at your existing foundation plants. If any are dead, dying, or struggling, out they go, then replace them with pollinator-friendly plants. Measure the vertical and horizontal spaces remaining and choose plants to fit those spaces at their mature size. You don’t want plants, even pollinator-friendly ones, that cover up windows or block doors. It’s a step often forgotten, leading to endless pruning of plants that never should have been planted in the first place. Unnecessary pruning can also result in snipping off flower buds, robbing pollinators of a valuable resource.

Extend the bed and plant in layers.

Determine whether you can add depth to your foundation plantings; can you extend the plant border forward? There is no reason that foundation plantings have to be skinny and flat. It is actually more aesthetically pleasing to create layers of plants that cascade as you move away from the house. Shrubs and small trees (depending on the space) can form the back layers, while flowering subshrubs, perennials, and even native grasses can fill in multiple layers moving forward. Consider low, flowering native groundcovers for the very front of the border.

Planting an enriched edge along a property line

Create a plant list based on available space.

Traditionally, plants used next to a building are shrubs, especially nonflowering evergreen shrubs. You can make better choices with flowering native evergreens that benefit pollinators. In the eastern United States, inkberry (Ilex glabra) and yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) are two examples. Manzanitas (Arctostaphylos spp.) can be used in some western states as wildlife-friendly screens or hedges. For even more plant choices for pollinators, mix it up with a combination of evergreen and deciduous shrubs. Deciduous flowering shrubs that are densely branched or have colorful winter stems like red osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) can make up for the loss of evergreen coverage, if that is a concern.

Your pollinator-friendly foundation border can be as deep as you like, given available space. The same pollinator planting principles apply: group the same species to create floral targets while creating a diversity of bloom throughout the growing season. You can turn a lifeless foundation planting into a pollinator paradise!

Enrich landscape edges

The edges of landscapes along property lines offer an opportunity to juice up pollinator resources with new planting beds. A continuous expanse of lifeless lawn from one property to another is an out-of-date concept with low ecological value. Adding more extensive pollinator gardens along your property lines and along any woodland edges provides more resources to pollinators while increasing visual interest and privacy.

Create layers with pollinator plants.

Add more layers of flowering plants by extending an existing plant bed forward. If existing plants in the back of the bed are on the short side, you can either add even shorter layers in front or you can transplant those existing plants and incorporate them in a new garden bed design. How you choose to layer will depend on the angles from which you are viewing the garden bed. If the bed has a 180-degree view, the taller plants will likely look better in the center; otherwise, taller plants often look best in the back.

Woodland edges offer another opportunity to layer with pollinator plants. Frequently, these edges end abruptly as tall trees meet flat lawn. Add more dimensions with a flowering shrub layer in front of existing trees and continue to extend the bed forward with tall shrubs, smaller shrubs, flowering perennials and grasses, and then flowering ground covers. When creating layers in any landscape, don’t forget to include larval host plants, many of which are trees and shrubs.

Pollinator-Friendly Lawn Alternatives

Reducing or eliminating turfgrass lawns in favor of pollinator gardens could be the greatest ecological achievement of our time. You can help start the trend! To be fair, no native pollinator-friendly lawn alternatives function exactly like turfgrass lawns. If you have lawn that you really use for pets or recreation, keep what you need and lose the rest. Whatever lawn you keep, manage it organically (pesticide free).

Shorter flowering perennials can be good alternatives to lawn.

Determine sight lines and plant heights

Lawn replacements don’t have to look like lawn, and they don’t have to be short. When deciding on lawn alternatives, consider plant heights and the sight lines of your landscape. What views do you have that you don’t want to obscure? What views would you like to create with plantings—perhaps a beautiful view of flowering plants from a patio? Do practical considerations, such as needing a clear view when backing out of a driveway, limit plant height in certain areas? Your tastes and practical limitations will dictate whether lawn alternatives are short, tall, or somewhere in between.

Decide on a naturalistic or more formal look

If your taste runs to shorter plants and a more formal look, a mixture of short, flowering ground covers designed in sizeable groupings might appeal to you. Native ground covers like pussy-toes (Antennaria spp.), creeping phlox (Phlox stolonifera), or heath aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides) might be good candidates, depending on your region. If you prefer a more naturalistic look, perhaps a tall native meadow with serpentine paths would inspire you while also feeding pollinators.

Pussy-toes (Antennaria plantaginifolia) is a pollinator-friendly lawn alternative and a larval host plant.

Don’t replace one monoculture with another

To get started, keep in mind this important guideline: don’t replace one monoculture (the lawn) with another monoculture. Biodiversity—a diverse array of native plants that will attract and support a diverse array of pollinators and other wildlife—is critical for healthy ecosystems. Keep the principle of floral balance in mind—plant diversely but plant sufficiently.

Removing turfgrass

You don’t have to replace a huge area of lawn at one time. Choose an area to work on and start your preparation. Avoid herbicides to kill the turfgrass; instead, use the sheet mulching technique of layering cardboard or newspaper, compost, and mulch to smother and kill the grass over time. You can plant right into the material when it has decayed after several months. For a faster method of turf removal, use a sod cutter that cuts deeply enough to lift up grass roots, and plant away.

Meadows and Meadowscapes

Many types of meadow ecosystems can be found in the world, but we typically think of a meadow as an open landscape brimming with native grasses and flowering perennials, with few, if any, trees or shrubs. We don’t often think of planting meadows in suburban or urban landscapes, but meadows can be sized and tamed to fit more managed landscapes as pollinator-friendly alternatives to lifeless lawns. A “freedom” lawn where you simply stop mowing turfgrass does not make a meadow. That’s just an overgrown, tall lawn with nonnative grass species and weeds. Meadows take time to establish and must be managed. Refer to the appendix for additional resources that can help.

Meadowscape with plant repetition

Plan your meadowscape for pollinators

A meadowscape is a meadowlike garden that incorporates many elements of naturally occurring meadows, but it may be more intentionally planted and managed. No hard-and-fast rules exist for creating a meadowscape, but a typical Pollinator Victory Garden meadowscape has the following features:

• full sun conditions (six-plus hours a day of direct sunlight)

• reasonably level landscape (hillsides can work by using short meadow plants)

• an absence of trees or shrubs

• soil with low fertility (low organic matter)

• flowering native perennials and biennials (approximately 60 percent)

• native grasses (approximately 40 percent)

• a diversity of native plants with at least three species in bloom at the same time

• a succession of bloom from late spring through fall

• a random assemblage of plants

Some meadows occur in dry areas, others on wet sites, and some have a combination of soil moisture conditions. In general, very fertile landscapes with a high percentage of organic matter (do a soil test first!) do not favor the majority of native grasses, nor do shady conditions. There are regional exceptions.

Choose the style of your meadow

Naturally occurring meadows have an erratic collection of plants, sometimes with pockets of specific species, but the overall effect is quite random. Meadowscapes can be planted this way or have a more designed look. While plant groupings are easiest for pollinators to find, those with floral constancy, such as bees and butterflies, will have no trouble finding the same species of plant repeated throughout a meadow or meadowscape. One advantage to a random floral pattern is reduced deer browse; deer find no obvious, easy targets to munch down.

The plant species you select (runners vs. clumpers; prolific reseeders), the plant formats you use (seeds, plugs, small perennials), and plant placement all contribute to the design. Since meadows and meadowscapes are dynamic communities, they will evolve and change appearance over time.

Pick out meadow plants

While flowering native perennials and biennials (forbs) are the go-to plants for pollinators, native grasses are an important component of native meadows and meadowscapes. Native grasses provide a matrix aboveground and belowground, supporting and knitting together a complex, interactive community of plants. Their deep roots are also very effective at preventing soil erosion. Most meadows consist of at least 40 percent native grasses. Fortunately, many native grasses are also larval host plants and seed sources for birds and small mammals, as well as habitat for many creatures.

Plant the meadowscape with seeds or plants

Meadowscapes planted with seeds are the most cost effective, random, and naturalistic. Seeded meadows also require the most initial management and take longer to completely establish—typically several years.

Meadowscapes planted with perennial plugs or small plants are a bit more expensive, can be more intentionally designed, and can establish within a growing season or two, depending on the time of year they are planted. When designing a meadow, consider creating a path within it so you can see the pollinator action up close.

If you like the idea of a meadowscape but feel the need for a neater aesthetic, try a “meadowish” approach. Use plant species typically found in meadows (such as native penstemons, coneflowers, goldenrods, asters, grasses, and so on), but group each species into intentional swaths using live plants; think of a perennial bed that has been “meadowfied.”

Convert an unusable hillside into a meadow

If you have an unusable hillside currently planted in turfgrass, consider planting a low meadowscape to help pollinators while ending the nightmare of mowing a slope. Short native perennials and grasses, such as tickseed (Coreopsis spp.) and prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) work well and will hold soil and prevent erosion when thickly planted.

Maintain the meadow for longevity

After establishment (once plants have all rooted and filled in), meadows and meadowscapes must be periodically cut back, typically once a year in early spring. If this cutting is not done, woody plants may soon encroach on the meadow. Keep the perennials and grasses standing through winter to provide habitat and seeds for wildlife. Meadows of all kinds are slow to start in the spring; most meadow species, especially native grasses, are warm-season plants. In spring, for larger meadows, consider cutting smaller areas back over a period of weeks, allowing hibernating species to wake up and leave without injury.

Container Gardening for Pollinators

No garden? No problem! You can still have a pollinator garden. Patios, porches, and even rooftops can all be havens for pollinators. Even if you have a landscape you can convert to a pollinator-friendly garden, you may want to extend your pollinator garden by planting in containers (pots). When you run out of space in the garden, start planting in containers!

Pollinator container gardens can be integrated with pollinator landscape plantings.

Pollinator gardening in containers has many benefits. Pots are usually mobile, so you can change their location. In a spot with no soil, you can plant a flowering vine on a trellised wall or a fence. Containers allow you to bring plants closer to your living space so that you can enjoy them and watch pollinators more closely. The soil mix in containers can be easily amended, allowing you to plant species that would not thrive in your locale.

Select containers

Choose containers that are frost proof and can be left outdoors in cold weather. Weatherproof composite pots come in many beautiful designs; some even emulate antique garden containers. Leave perennials in these containers year-round. That way, no expensive replanting is needed; just add some compost or other organic matter periodically to keep the soil biology going in the container. But don’t forget that plants in pots need more water than plants in open soil.

Select the largest possible containers, both deep and wide, that will fit into the space you have. Some native plant roots, such as those of native grasses, are quite expansive and need more room as they grow. A large container may also allow you to fill it with a grouping of the same species for a pollinator target, or multiple species of plants selected to bloom at different times of the growing season.

Select appropriate plants

Long-blooming plants such as coneflower (Echinacea spp.) are particularly good choices for pollinator container gardening. Emphasize pollinator favorites such as giant hyssop (Agastache spp.) since space limitations may prevent you from planting a diverse array of plants. While they’re not the first choice for an in-ground garden, dwarf cultivars of native plants can be highly useful in containers—but make sure they are not overly bred and devoid of nectar and pollen. A 4 foot (1.25 meter)-tall garden phlox may be tough to use in a pot, but a 1 foot (30 cm)-tall, nectar-filled native cultivar might be perfect.

Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum), a pollinator favorite

A popular way to plant in containers is the “thriller, spiller, filler” method, which can apply to pollinator plants as well. Use a taller plant as the thriller, a medium-height plant as a filler, and a cascading plant as a spiller. Depending on your region, a possible planting could be anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) as a thriller, hairy beardtongue (Penstemon hirsutus) as a filler, and heath aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides, ‘Snow Flurry’) as a spiller. This grouping would provide a spring bloom, a summer bloom, and a fall bloom, keeping pollinators fed and providing multi-season visual interest.

Group containers together to achieve a fuller effect; you’ll appreciate their lushness as will the pollinators that come to find nectar and pollen.

Growing and Maintaining a Pollinator Victory Garden

All newly-planted plants, even native plants, need your attention for the first year or two. When Mother Nature doesn’t deliver enough rain, consider supplemental watering in the first two years to ensure that roots establish well. Once native plants are well-rooted, they will be very low maintenance. If you have planted from seed, be patient; it may take a while until seeds germinate and the plants fill in.

Keep nectar flowing by planting the right plant in the right place with proper moisture.

A seasonal calendar will help you establish a good maintenance regimen. At right are some tips to keep your garden and the pollinators healthy and happy for years to come.

A Few Words on Pesticides, Pollinators, and Alternatives

Pesticides and pollinators do not make a good combination. Keep pesticides out of your Pollinator Victory Garden. Many pesticides are toxic to bees and other pollinators, while some pesticides fall short of being lethal to pollinators but affect their ability to function normally. Every year millions of pounds of pesticides, including insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, and rodenticides, are used on farms and roadsides, as well as residential, municipal, and corporate landscapes. In many cases, pesticides are applied automatically even if there is no apparent problem to treat. Don’t follow the crowd when it comes to pesticide use if you want to have a safe and supportive Pollinator Victory Garden.

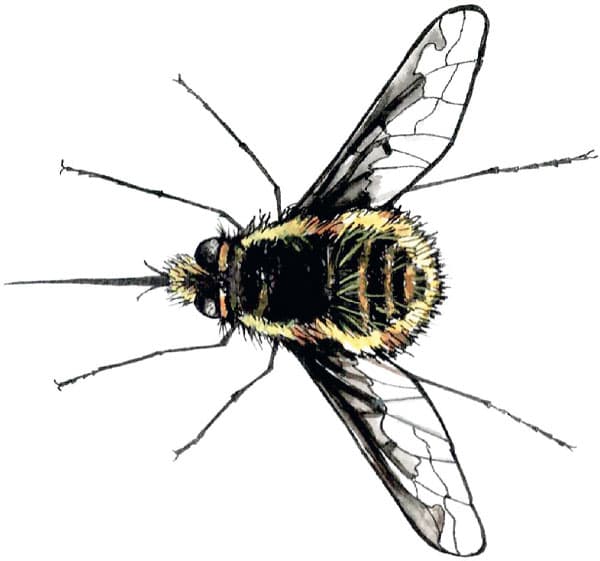

Lady beetle larva: a beneficial insect that provides natural pest control

Avoid systemic pesticides

Systemic pesticides are particularly problematic because they have the ability to persist for months and sometimes for years. A newer class of systemic pesticides called neonicotinoids or neonics has received much attention for its lethal and sublethal effects on bees. Neonics are widely used insecticides that are absorbed by plants upon application and taken up in a plant’s vascular system. Neonics can be present in nectar and pollen even if applied to a plant weeks before bloom. These poisons can even affect untreated plants nearby. When buying plants, insist that they are neonic free.

Determine if there really is a problem that needs to be treated

To protect pollinators, first assess any perceived damage in your landscape to determine if it is really damage at all. A hole in a leaf might be just a butterfly caterpillar feeding on a larval host plant or a leafcutter bee taking bits of leaf for her nest. A healthy, thriving landscape is not a perfect landscape. If you determine that you have a plant pest or disease that you absolutely must treat, avoid synthetic, man-made pesticides. Use organic pesticides sparingly and carefully; they are not benign. If you feel that you must use a pesticide, choose an organic product that treats only the targeted problem without causing collateral damage to beneficial creatures such as pollinators.

Keep pests and diseases in check naturally

Pollinators face many challenges to their survival. Eliminating pesticides from your garden gives them a fighting chance. Use these alternative methods to keep pests and diseases in check:

• Buy plants that are disease free.

• Optimize plant health by planting the right plant in the right place.

• Use good cultural garden practices to keep problems from spreading, like removing dead leaves infected with fungal spores.

• Take advantage of nature’s pest control by attracting natural enemies (predatory and parasitic beneficial insects) with native plants.

• Plant for birds, the majority of which feed insects to their young and may consume insects themselves.

• Tolerate some damage in your landscape.

Voltaire had it right: perfect is the enemy of good. We are not perfect, and our landscapes don’t have to be either. Rachel Carson warned about pesticides more than fifty years ago in her book Silent Spring. Let’s heed her warning. If it’s not good for pollinators, it’s not good for us.

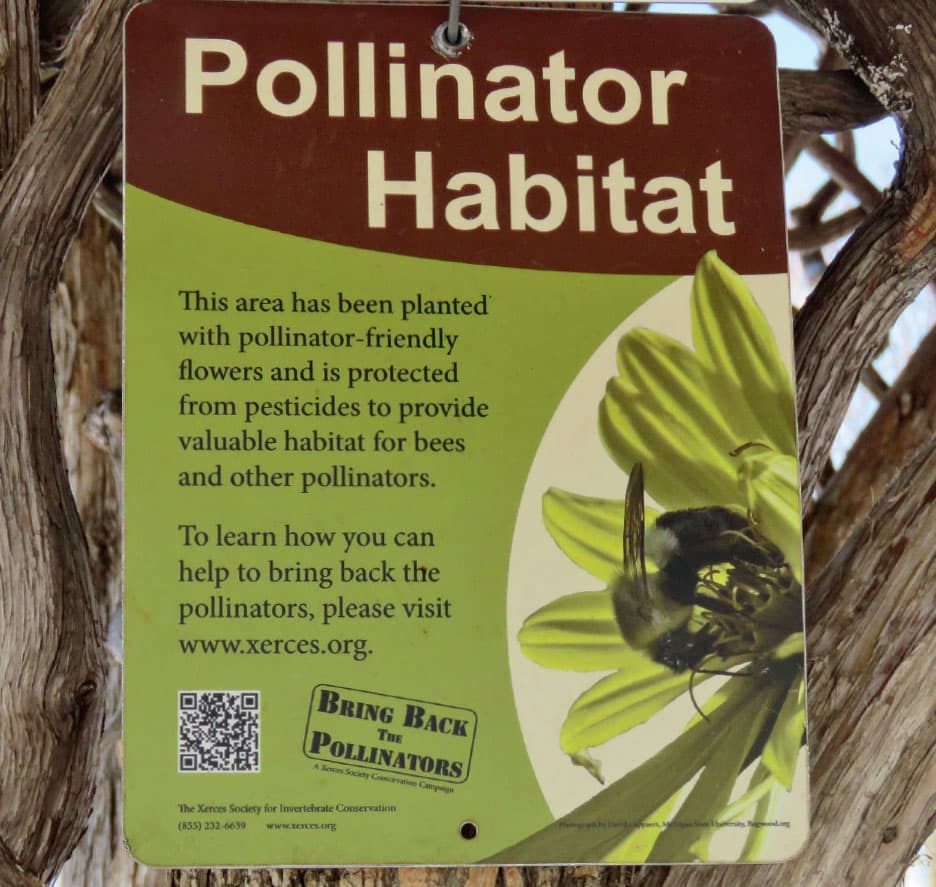

Install Pollinator Signage

Signage is an underused but powerful tool in ecological gardening. A simple sign at the end of your driveway, on a fence, or even on your house that declares you are gardening for pollinators will catch the attention of many, many people.

Motivate others to garden for pollinators: Install a pollinator sign.

One sign to consider is the “Pollinator Habitat” sign from the Xerces Society, a nonprofit invertebrate conservation organization. This 9- x 12-inch (23 x 30 cm) sign states: This area has been planted with pollinator-friendly flowers and is protected from pesticides to provide habitat for bees and other pollinators. This is a message that gets people thinking and, ideally, acting.

When we change our landscaping practices, like replacing a lawn or leaving perennials standing through winter, it can confuse neighbors, family members, and friends. Once you show that you are gardening with a purpose, others start to connect the ecological dots. Take the opportunity to explain the basics of pollinator gardening and why it is so important.

A variety of signs are available for purchase in addition to the Xerces sign. The North American Butterfly Association has a “Certified Butterfly Garden” sign if you meet its requirements, Beyond Pesticides offers a “Pesticide Free Zone” sign, and you can even buy a “Pollinator Friendly Garden” sign on Amazon.

Share Your Garden

Those same neighbors, family members, and friends may well appreciate an invitation to visit your garden to see what you have created and learn how they might emulate your efforts. It’s time to have a garden party! Keep it simple or go crazy and make it a pollinator extravaganza. You might want to pick up some samples of your best-performing pollinator plants at a local nursery and offer them for sale at the event. Contact your local Master Gardener organization and ask if they have a speaker who might visit to talk to your guests and lead a tour of your garden.

Some neighborhood associations have garden tours; if yours doesn’t, suggest that they start one. Your Pollinator Victory Garden can be a valuable learning opportunity for homeowners who are still planting invasive plants and using pesticides. Other organizations, such as book clubs, may be interested as well. Book clubs don’t have to meet indoors, and they don’t have to read only fiction. Offer to host a Pollinator Victory Garden reading-and-learning experience.

Find Volunteer Opportunities

Nonprofit organizations, schools, churches, libraries, community gardens, and even municipalities often have land that is not being used. These are all opportunities to transition lifeless space into Pollinator Victory Gardens. Make a plan, set a budget, and ensure that there will be ongoing maintenance to have a successful project. If you don’t want to start a pollinator project yourself, join an environmental organization like the Audubon Society or the Sierra Club, which may have chapters with ongoing projects. Join a local garden club and help lead the effort to garden with purpose for pollinators.

Do you feel like knocking on doors or at least affixing informational tags to doorknobs? One organization in the northeastern United States has volunteers who place pollinator information tags on the doors of local residents, explaining why pollinators are important and giving suggestions on how to help pollinators.

Perhaps you would like to effect change for pollinators on a larger scale. Consider joining the local planning commission or environmental board as a pollinator advocate. You might pitch a pollinator demonstration garden to get people on board. You can show how pollinators are ecologically and economically important to every community.

Whether your efforts as a pollinator advocate are local, regional, or national, they will make a difference!

Creating Pollinator Pathways

The lack of connectivity from one landscape to another for wildlife, including pollinators, has been a huge problem for many decades. Where connected natural areas once existed, there are new housing developments, shopping centers, office buildings, and roads. Connectivity seems to be continuously fragmented in our modern world, resulting in disconnected patches that pollinators and other wildlife cannot reach.

Create pollinator pathways that connect residential, commercial, and municipal landscapes.

Wildlife suffers when landscape fragmentation occurs, losing habitat and resources, with a resulting increase in mortality. Landscape fragmentation takes a toll not just on wildlife but also on the health of entire ecosystems. The concept of using wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented landscapes has existed for decades, though it’s mainly used on public lands. A wildlife corridor is a link between two or more larger areas of wildlife habitat to give wildlife safe passage and needed resources.

This same approach can be used to create continuous vegetative corridors of pesticide-free pollinator gardens that extend from one property to the next, from one town to the next. In late 2007, an innovative designer based in Seattle named Sarah Bergmann set about creating what may have been the first pollinator pathway, a 1-mile (1.6 km) long, 12-foot (3.7 m) wide corridor of pollinator plants.

That effort seems to have sparked additional pollinator pathways organized by volunteers from dozens of town conservation organizations in the northeastern United States.

Another terrific program helping to connect pollinator landscapes is Bee City USA®, an initiative of The Xerces Society. Launched in 2012 by founder Phyllis Stiles, its mission is to galvanize communities to sustain pollinators by providing “healthy habitat, rich in a variety of native plants and free to nearly free of pesticides.” Incorporated cities, towns, counties, and communities can become designated as Bee City USA affiliates through an application, resolution, and implementation process. College campuses can similarly become certified as a Bee Campus USA. Across the United States, there are now almost 100 Bee Cities and 80 Bee Campuses. Each of these affiliates started with a local pollinator champion. You could be that champion for your own community.

Pollinator Pathway Tips

• Check with local conservation organizations to see if a pollinator pathway exists in your town. If so, join it, get your property on their map, and ask if signage is available for your yard.

• If no pathway currently exists, start one by coordinating with local conservation groups. Your landscape may become the genesis for a future pathway. Visit www.pollinator-pathway.org to get ideas on forming, promoting, and running a pollinator pathway.

• Focus on connectivity. Fragmented landscapes with unconnected “pollinator pockets” limit pollinator resources and may actually put pollinators in harm’s way. Pollinator pathways of connected gardens with continuous habitat improve pollinator resources dramatically.

• Start your own pollinator corridor by asking (or helping) next-door neighbors transition at least part of their lawn to pollinator habitat. In most neighborhoods, lawns are already connected corridors from one property to another. Why not make those spaces productive for pollinators and beneficial to your ecosystem?

• Host a pollinator pathway party in your Pollinator Victory Garden to get your community, neighbors, and friends engaged. Share both digital and printed information with them about native gardening for pollinators. Have pollinator-friendly native plants available to get your guests started.

• Use signage that promotes your local pollinator pathway. A sign that says “I’m on the (town name) Pollinator Pathway” is a great way to show neighbors, family, and friends that you are gardening with a purpose and you are gardening for and with your community. They may become inspired, too!

You can help leverage the pollinator pathway movement—if more homeowners, businesses, and municipalities create and connect pollinator gardens, pollinators will benefit and ecological health will improve.