2 Providing Pollinators with a Place to Live

Habitat is a term that frequently appears when pollinators are being discussed. But what is habitat? Simply put, habitat is the natural environment where an organism, in this case a pollinator, lives, and where it can find the resources it needs: food, shelter, resting places, and safe places to mate and reproduce. Habitat includes more than flowers.

Understanding Habitat as an Ecosystem

Any residential, commercial, or institutional landscape is more than a combination of trees, shrubs, perennials, and (likely) lawn; it’s an ecosystem where every living thing is interconnected. And your ecosystem can provide habitat for many types of wildlife, including pollinators.

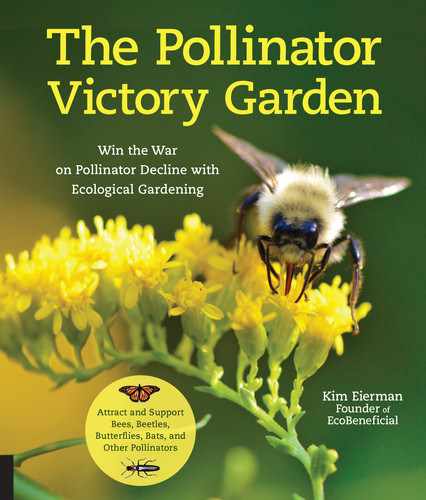

Pollinator Victory Gardens provide multiple types of plants and pollinator habitats.

Most of us have landscapes that can function, at least to a limited degree, as pollinator habitat. But there is a tremendous difference between quality pollinator habitat and poor pollinator habitat. A landscape dominated by a large turfgrass lawn will never be a high-quality pollinator habitat; you could improve it by allowing flowering weeds to exist in the lawn, but that still won’t be enough. By considering what pollinators need, you can create habitats that are exceptional versus merely marginal.

What Pollinators Need in a Habitat

Habitats don’t exist in a vacuum; think of your entire landscape as habitat, not just the perennial garden. Yes, flower-filled perennial areas will see a lot more obvious pollinator activity, but pollinators use many other parts of your landscape that you may not notice. Trees and shrubs can offer flower rewards, food for butterfly and moth caterpillars, nesting spots for pollinating birds, resting and overwintering sites for insects, and protection from strong winds. Areas of bare or lightly vegetated soil, brush piles, and plants with hollow stems provide places for some pollinators to nest. Bunches of native grass, leaf litter from trees, and piles of twigs can serve as overwintering sites for some pollinator species.

When you improve your ecosystem for pollinators, the overall ecological health of your landscape improves, benefiting all plant and animal life. To keep pollinators and other wildlife healthy, your landscape, ideally, should be pesticide free.

Habitat Regionality

Pollinator habitats in Arizona should not look like pollinator habitats in New Jersey. Habitats are most successful when they reflect the country and the region in which they exist. Climate, geography, indigenous pollinators, and the native plants they have evolved with, differ from region to region. Using resources in this book’s appendix, you can determine the ecological region you live in, and the plants and animals that are native to that region. This provides some context for the type of pollinator habitats most suitable for your locale. Remember, evolutionary connections matter.

Creating Habitat for Egg Laying and Nesting

All pollinators need a safe place to reproduce, which is one of the most important aspects of your Pollinator Victory Garden. Simply because you see pollinators nectaring in your landscape does not mean that the conditions are right for egg laying and nesting.

Native willows (Salix species) are larval host plants for over 450 species of caterpillars and an early source of nectar for bees.

Butterfly and Moth Habitats for Egg Laying

Butterflies and moths don’t make nests like some other pollinators, but they do need a place to lay their eggs. The majority of butterflies and moths lay eggs on specific plants that have evolved to feed the caterpillars that emerge from these eggs. These plants are called larval host plants (more about this in chapter 3). If caterpillars don’t have their larval host plants, they cannot survive.

What makes good butterfly and moth egg-laying habitat? Larval host plants that are pesticide free. If you plant only flowers for adult butterflies and moths to nectar on and don’t have larval host plants, you don’t have a pollinator garden to support butterflies and moths.

Native Bee Habitats for Egg Laying and Nesting

All native bees in North America build nests, except cuckoo bees, which lay their eggs in the nests of other bee species. Since the vast majority of native bees are solitary, most bees nest alone, but bumble bees are an exception; they nest in small groups of fifty to four hundred. Female native bees build nests and provision the nests with food for their young, while male bees find other spots to rest and sleep on, including flowers, stems, and twigs.

The majority of native bees nest in the ground.

Native bees nest either in the ground or in cavities. The majority (70 percent of all native bee species in North America, or 2,800 of the 4,000 species of native bees) are ground nesters. The other 30 percent, including bumble bees, are cavity nesters. There are a lot of bees to provide habitat for in your pollinator garden! You may have hundreds or even thousands of individual bees using your landscape. The good news is that you don’t have to do much to give them a place to live.

Providing habitat for ground-nesting bees

The majority of native bees are ground nesters that need easy access to soil to excavate their nests. Reserve existing patches of bare soil in a sunny spot or create an expanse of bare soil—even a few square feet (m) can work. Sandy or loamy soils are top choices; rich soils and clay soils are more difficult for bees to excavate and may get waterlogged. A sunny, quiet location, free of mowers, noisy equipment, and foot traffic, is ideal. If naked soil seems too unsightly, you can plant the area very sparsely and bees may still use it. Best to leave the area bare but screen it with some flowering shrubs. Just make sure not to shade out the bee habitat.

Avoid using mulch or landscape fabric in bee nesting areas as both will repel bees. All habitat should be left quiet and undisturbed, with no tilling or cleaning up, even in the off season. Think of this area as wild habitat instead of a manicured garden. If you succeed, you may support hundreds of bees underground.

Providing habitat for cavity-nesting bees

Thirty percent of native bees are cavity nesters that use an array of resources for their nests. Many like pre-existing cavities such as abandoned beetle tunnels in fallen logs, dead trees, and stumps; others may use gaps in stone walls, abandoned bird nests, hollow trees, spaces within rotting wood, dense brush piles, or plant debris. Some bees even nest inside pithy (spongy) plant stems.

Tree snags

Consider preserving dead or dying trees as bee habitat. Such trees are referred to as snags and can provide valuable habitat for pollinators and many other creatures. A hollow expanse in a dead tree may give bumble bees or even feral honey bees a safe home. Beetles like to tunnel in dead wood, leaving a future home for cavity-nesting bees. Any snag located well away from your house, where it won’t harm anyone or anything if it falls, is worthy of keeping. If the snag is too tall for your comfort, cut it back to a height that is manageable; wildlife will still use it. Leave fallen logs in place as a habitat resource. As they decay, they often become quite beautiful with an abundance of plants growing in the rich medium. Just consider them nature’s free planters.

Old beetle tunnels in a dead tree offer habitat for cavity-nesting bees.

Pithy stems

Pithy stems from plants such as elderberry, raspberry, hydrangea, and Joe Pye weed are highly useful to some cavity-nesting bees. You can leave the dead stems from plants like these in place over the winter or collect and bundle them for bee habitats. As a general practice, leave any perennials standing in the garden through winter to provide habitat for insects and seed for birds. They can then be cut back in early spring. It’s best to stagger your early season stem cutting over a period of time, at least a week or two, to ensure that temperatures have warmed sufficiently to allow insect visitors to become active.

Ceratina bees nesting in a pithy plant stem.

Brush piles

Dense brush piles are a good potential habitat for bumble bees. You may not have any because conventional wisdom dictates that we clean up our landscapes, removing any dead trees and branches. This practice, however, is counterproductive to good ecological practices. If you don’t have brush piles in your landscape, create them! Brush piles don’t have to be huge; whenever you prune woody plants to remove dead wood, keep the branches. You can secure them tightly in place or tie them together. To successfully shelter bees, the piles must be fairly tight and dense, providing cavities that shelter bees from rain. If you are handy, try making a wattle fence, which is a wooden fence made by weaving thin branches together to form a lattice, which will also provide shelter.

Brush piles can be good habitat for bumble bees.

Man-made habitats for cavity nesters

Man-made habitats for cavity nesters can be made or purchased. Wood blocks drilled with holes in a range of diameters are called nest boxes. Hollow plant stems can be bundled together to form stem bundles. There is a bit of an art and science to these artificial habitats, including maintaining proper hygeine, so check the appendix for suggested resources.

Man-made bee hotels can serve as habitat for cavity-nesting bees.

Providing Habitat for European Honey Bees

European honey bees (Apis millifera) have an arrangement for nesting and raising their young that’s very different from that of wild native bees of North America. When they’re managed by a beekeeper for honey production or pollination services, honey bees live in man-made beehives that usually look like stacked boxes. They lay their eggs and raise their young in those hives.

There are also feral honey bees that are no longer managed by beekeepers. These feral honey bees often live and reproduce in tree cavities as a large group, which is yet another reason to leave dead or dying trees in place as long as the trees pose no hazard.

Honey bees are communal, the most social bees, and may live in colonies of 50,000 or more individuals depending on the season. You don’t have to be a beekeeper to help honey bees. By keeping your landscape pesticide free and filled with flowering plants, you can support both native bees and European honey bees. Since there is competition for resources among native bees and honey bees, plant intensely if you keep honey bees or have neighbors who do.

Providing Habitat for Sheltering and Warming

In their active seasons, pollinators require safe places to rest, warm their bodies, and shelter in bad weather. When the weather is fine, insects like bees, moths, and wasps may rest or sleep on flowers overnight. In the case of bees, they hold on to the flowers with their legs or their mandibles (jaws) and rest. Sometimes bees even sleep in flowers that close up for the night, which may be a way to stay safe from predators. We can design landscapes to help them with all of these needs.

Butterflies don’t have nests, and they don’t even sleep—they rest with their eyes open. Butterflies look for a protected place to rest among foliage, or they hang upside down from leaves or twigs of trees and shrubs. While butterflies are active during the day, most moths are nocturnal and find similar protected places to shelter during the day.

Sheltering and Windbreaks

When weather is bad, pollinators are quite vulnerable. Consider the small size of most pollinators and how exposed they are to high winds. A monarch butterfly can weigh as little as 0.009 ounce (255 mg), while a bee might weigh only 0.003 ounce (85 mg). Pollinators that have nests, like bees, wasps, and hummingbirds, may not be able to return to their safe haven in time to avoid winds. Butterflies are especially vulnerable to wind because they lack nests. But with some planning, you can plant vegetative windbreaks to help shelter and protect pollinators on windy days.

Windbreaks serve many purposes. When protected from wind, pollinators not only have a greater chance of survival but also are able to conserve energy, which allows them to forage more on flowers. Windbreaks also provide conditions that are a bit warmer, which allows cold-blooded insect pollinators like bees to be active for longer periods.

Plants for windbreaks

Trees and shrubs are particularly effective as windbreaks. Flowering woody plants have the extra benefit of providing additional nectar and pollen, further expanding the forage habitat. In especially windy areas, the cover of evergreen trees and shrubs can be useful, and some also flower.

Native grasses can serve as windbreaks and bee nesting sites.

Tall native grasses can serve not only as windbreaks but also as bee habitat. Native bunchgrasses, such as prairie dropseed, are good overwintering sites for bumble bee queens, which may nest at the base of the grass. Many native grasses are larval host plants for skippers, a large butterfly family. Native grasses perform even more ecological functions as their deep roots hold moisture and reduce flooding and soil erosion.

Creating a windbreak

There is no magic formula or exact design for creating vegetative windbreaks for pollinators; it can be accomplished with simple plantings. Windbreaks near pollinator nesting sites are helpful, but make sure not to site plants where they cast shade on nesting habitat. Warm-season native grasses can accomplish this as they are not too tall but still tall enough to provide shelter.

Assess the windy areas of your landscape, especially around foraging habitat. Staggered rows of diverse flowering trees and shrubs can be useful in these locations. The more diverse the planting, the better, to avoid monocultures of shrubs positioned side by side like little soldiers. You are looking to create a windbreak, not a green wall! Monocultures limit ecosystem functioning (your landscape is an ecosystem) and a monoculture planting may be wiped out by a single pest or disease.

Habitat for Warming

Pollinating insects are cold blooded and need to warm up to become active. Although some bees, like bumble bees, can tolerate less-than-ideal weather conditions, honey bees may only be active at temperatures of 54°F (12.2°C) or higher, and butterflies reportedly need a temperature of 55°F (12.7°C) or higher to fly. Providing habitat in sunny spots helps them warm up on days when temperatures are questionable; this is a major reason for planting forage in sun-filled areas.

Butterflies, like this red admiral, bask on rocks to warm their bodies.

Rocks can be another aid for warming and are underused as a design feature in gardens. Boulders and large rocks, which stay warm longer, can be nicely positioned to complement plantings and create more visual garden interest. Place them in sunny locations to create a basking area that many pollinators will appreciate.

Creating Overwintering Habitats

In colder climates, most pollinating insects die before winter sets in. But many do survive over the winter using a variety of survival strategies. Here are some ways various types of pollinators overwinter.

Loose bark of shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) offers habitat to pollinators like butterflies.

Butterflies and Moths

Most butterflies overwinter as caterpillars (larval stage) or as a chrysalis (pupal stage), but some species overwinter as eggs or adults. Many species undergo diapause, a period of suspended development that usually occurs during cold winter months. Mourning cloaks, anglewings, tortoiseshells, and eastern comma butterflies can overwinter as adults in colder climates as they have special chemicals in their bodies akin to antifreeze that prevent them from freezing. Some butterfly species migrate, including monarchs, which migrate the longest distances; shorter-distance migrators include painted ladies, buckeyes, and cloudless sulphurs.

Adult overwintering

Butterflies and moths that overwinter as adults often shelter in the crevices of dead trees, in hollow logs, between large gaps in rocks, or sometimes in leaf litter. Some adult butterflies find cover under the exfoliating bark of trees. Shagbark hickory, a tree native to the eastern United States, has loose bark that shelters overwintering butterfly adults. Piles of logs can also make excellent winter habitat for adult butterflies.

Leaf litter can be valuable overwintering habitat for some pollinators.

Caterpillar overwintering

Many caterpillars and almost all moth caterpillars overwinter in leaf litter; pupae typically overwinter suspended from twigs or branches but may also be found in piles of dead leaves. Leaf litter is a refuge for many insects, not only butterflies and moths, and that’s a great reason to leave fallen leaves in place in your yard. Resist the urge to chop up or mulch those leaves, as you may unwittingly kill adult or immature butterflies or moths. Raking and mowing in fall may also remove leaf litter winter habitat that is so beneficial to these creatures.

Honey Bees and Bumble Bees

Honey bees are the most social bees and overwinter in the same location where they nest during their active season, which is either a man-made hive or, in the case of feral honey bees, a hollow tree or similar cavity. If weather turns warm in winter, honey bees emerge, looking for food.

Honey bee on wild plum (Prunus americana)

Bumble bees form much smaller colonies during their active season than honey bees but become solitary in winter. In the fall, a bumble bee colony produces new queens and male bees. Once queens and males mate, the newly mated queens survive but the other bees in the colony die. The mated queen finds a new nest, often a small underground spot obscured by leaf litter, where she overwinters by herself. Sometimes she nests under rocks or rotting logs or at the base of native grasses. Protect her overwintering habitat by leaving leaves and logs in place. Overwintering bumble bee queens, like overwintering adult butterflies, produce a natural chemical called glycerol that prevents their bodies from freezing in cold weather. In early spring the queen emerges from hibernation and finds a nesting site to lay her eggs.

Solitary Bees

Solitary bees live for about a year, most of which is spent in their developmental stages of egg, larva, and pupa. These bees are active as adults for only a short time—perhaps three to four weeks. Unlike honey bees and bumble bees, solitary bees of most species die as adults before winter arrives. Solitary female bees seal their eggs inside a burrow or nest cavity provisioned with a supply of pollen and nectar. Preserve their habitat undisturbed so new bees can successfully emerge in spring or summer.

Surviving solitary cavity-nesting bees, including mason bees, leafcutter bees, and small carpenter bees, overwinter as adults in their original nests in a state of diapause, or suspended development. Mason bees are particularly interesting since they may overwinter in waterproof cocoons. To help cavity-nesting bees, grow plants with pithy, spongy stems, such as elderberry and Joe Pye weed; keep trees and shrubs that have hollow voids or beetle tunnels, and consider providing bundled hollow tubes or man-made bee hotels (see the appendix for resources).