3 Providing Pollinators with Food to Eat

Habitat consists of a place for pollinators to live as well as a place for them to eat and get the nutrition they need to flourish. These habitats may be the same, can be overlapping, or may be more disconnected as is the case for honey bees, which will fly several miles, if necessary, to obtain food. In managed landscapes, the place to live and the place to eat (both habitats) should overlap and are equally important. In most cases, you can provide pollinators with both a place to live and a place to eat in the same general area.

What Pollinators Eat

Forage is the word for the food supply from flowers that pollinators eat. Foraging habitat is the dining room of your landscape, the parts of the garden where pollinators can find a meal.

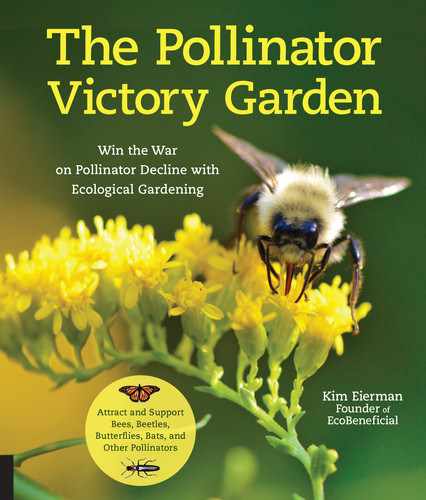

Pollinator habitat with plenty of pollinator forage

Nectar, Pollen, and Other Food

The main pollinator foods are nectar (for energy) and pollen (for protein), which are produced by most flowering plants. Some flowering plants, such as St. John’s wort and shooting star, produce only pollen, but that still has value for pollinators. Roses, which are often mentioned as pollinator-friendly plants, have little nectar but reward pollinators mostly with pollen. For pollinators, stick with native roses that have simple floral structures and abundant pollen. Avoid hybrid roses, which often have little or no nectar or pollen, as well as more complex petal structures that make any forage hard to access.

In addition to nectar and pollen, some pollinators seek out nonfood resources from flowers. Floral oils produced by a limited number of flowering plants have evolved with specialist bees, which use them in their nest cavities. Plant resins from flowers or plant stems are collected by some bee species for the same purpose.

Differences in What Pollinators Eat

While honey bees and wild native bees eat both nectar and pollen, not all pollinators do. Most adult butterflies eat only nectar, while some neotropical butterflies feed on both nectar and pollen. Other species of butterflies prefer nonfloral foods, including tree sap. The majority of adult moths eat nectar, with the exception of species like wild silk moths that eat nothing at all, gaining the nutrition they need in their larval stage.

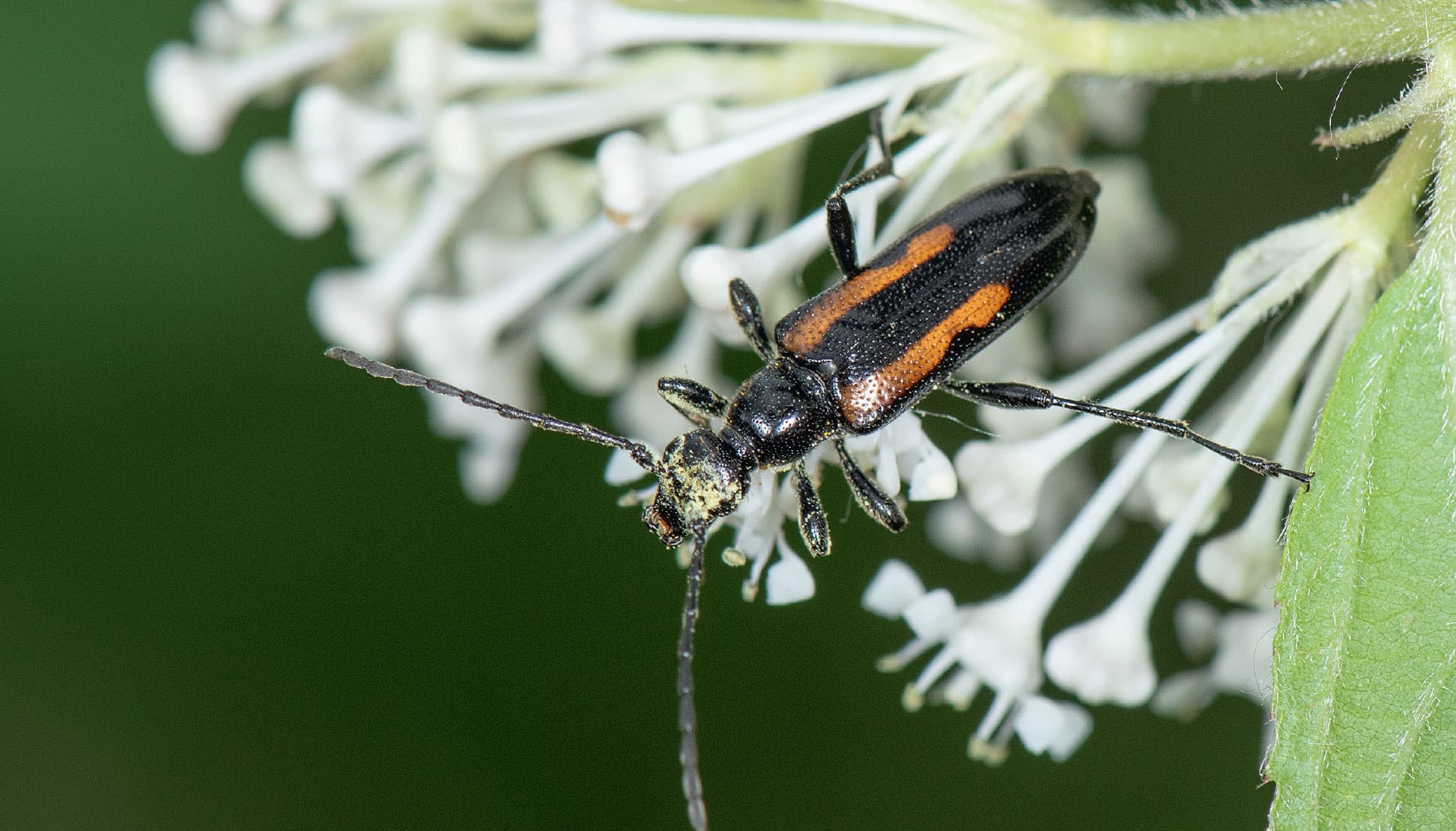

Some beetle species specialize in eating pollen while others may eat flower parts, like petals, as part of their diet. Wasps are primarily carnivores, mostly consuming insects, but they may also eat nectar, especially when food is scarce. Hummingbirds and pollinating bats feed on insects, nectar, and sometimes pollen.

How Pollinators Feed

Most pollinators feed multiple times a day and, in the case of bees, may make dozens of foraging missions daily. Some pollinator species are specialists on particular plants, while others are generalists, feeding on many different plants. An interesting exception is the bumble bee; although bumble bees are usually generalist foragers, individual bees in a bumble bee colony may specialize on certain plants.

Native plants such as coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) often attract a diversity of pollinators.

Some pollinators, including bumble bees, honey bees, and butterflies, have a feeding behavior called floral constancy, also known as floral fidelity. On each foraging trip, they look for one species of plant from which to eat. This is a clue to the gardener to plant more than one of any specific plant; otherwise, pollinators practicing floral constancy will not get enough nutrition and will expend more energy on more foraging missions. Pollinators benefit from groupings of plants at least 3 feet (0.28 m) square. Not all gardens have room to accomplish this—do the best that you can.

Choosing Plants for Pollinators

Choosing the best plants for your Pollinator Victory Garden is easier when you have an understanding of plant categories and the reasons for choosing particular plants over others. Native plants, nonnative plants, naturalized plants, straight species plants, cultivars, and hybrids all have different implications in a pollinator-friendly landscape.

“Plant the right plant in the right place” is a gardening mantra to remember. The plants you choose should be appropriate for your region and suitable to the particular site you are planting. And the plants you select should appeal to pollinators, at least some pollinators. There really is no “one size fits all” plant, as not every pollinator is attracted to or can use every pollinator plant.

Once you learn the key points of pollinator plant selection addressed in this chapter, you can make the best choices for your Pollinator Victory Garden. Spoiler alert: For best pollinator results, favor a diverse array of straight species plants native to your region and suitable for your landscape conditions.

Scorpionweed (Phacelia species) is particularly attractive to honey bees.

Columbine (Aquilegia candensis) is favored by hummingbirds.

Native Plants

Depending on whom you ask, the definitions of native, nonnative, and invasive plants may differ significantly. Federal Executive Order 11987 of the United States defines native species as “all species of plants and animals naturally occurring, either presently or historically, in any ecosystem of the United States.” The inclusion of the phrase “naturally occurring” is key to understanding what native is.

Swallowtail butterflies have evolved as the best pollinators of native flame azalea (Rhododendron calendulacuem).

A good working definition of native plant is a plant that has occurred naturally for hundreds or thousands of years in a particular region or ecosystem. The word native is best used with a geographic qualifier (such as “native to the Northeast,” “native to New York,” “native to Westchester County”). Plants found in the United States before European settlement are typically considered to be native to the United States. While a plant may be native to some states, it may not be suitable for planting in more distant states where it has not evolved. (See here for tips on determining which plants are native to your region.)

Benefits of native plants

Native plants are those plants that occur naturally without human introduction and have coevolved in local ecosystems, intricately interconnected to the living creatures around them. Without native plants and native landscapes, many other species cannot exist. As landscapes fill with lawns and other nonnative plants, eliminating the resources that native plants provide, many species suffer.

Within the past generation, both vertebrate and invertebrate species have drastically declined. Pollinator species have suffered a severe toll. Native plants have never been more important in supporting native pollinators and our local ecosystems. If evolution and the importance of biodiversity don’t convince you, below are some other reasons native plants are important.

Research suggests that native plants are four times more attractive to pollinators than nonnative plants. The evolutionary connections between native species are profound in some cases, not to mention the fact that native plants can offer more to an ecosystem than just nectar and pollen, and are best adapted to regional conditions.

Using native perennials and woody plants

The benefits of native plants are undeniable in a pollinator garden, but they are grossly underutilized in most landscapes. Your choices of natives include not only perennials but also native trees and shrubs. Think of your garden as your entire landscape, not just a discrete planting area where flowering perennials live. Masses of flowering native perennials will be a boon to pollinators but so will the native trees and shrubs you plant.

Many native trees and shrubs are larval host plants for butterflies and moths. The more host plants you can include in your pollinator landscape, the greater the number of butterfly and moth species you will support. Flowering native woody plants offer an abundance of flowers with a volume of bloom that can be hard to replicate with perennials, particularly in a small yard.

Incorporating more natives

Consider the areas of your landscape where you may have underperforming shrubs that could be easily replaced by native pollinator-friendly substitutes. A nonnative shrub with blooms that no pollinator visits is a good candidate to replace with a pollinator-enticing native alternative—perhaps a ninebark, a ceanothus, or a summersweet, depending on your region. Many lifeless foundation plantings are waiting to be transformed into pollinator buffets. Trees and shrubs that are not healthy can also be removed to make room for robust and ecological native pollinator plants.

When selecting native plants, consider the layers of the landscape and the native species you see in natural areas around you. Try to reflect those layers and species in some of your landscape. In much of the northeastern United States, natural areas have layers that start with canopy trees, transition downward to subcanopy trees, tall shrubs, and smaller shrubs, and then descend to the herbaceous layers of flowering perennials, grasses, sedges, and ground covers. Even prairies and deserts have layers, although they are harder to see. Emulate the natural layers you see in your region in your own landscape.

Nonnative Plants

A nonnative plant is one that has been introduced with human help, either intentionally or accidentally, to a new place or new type of habitat where it was not previously found. Another term for nonnative plant is alien plant; exotic plants are nonnatives that come from a different continent. Not all nonnative plants are invasive, nor do all nonnative plants naturalize; in fact, some nonnative plants are well behaved. Although flowering nonnative plants may provide nectar and pollen to generalist pollinators, they may not function ecologically in other ways that native plants do—as larval host plants, as preferred nesting sites, as sources of appropriate nutrition for migrating birds, and so on.

Bee nectaring on summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), a native plant

When considering nonnative plants with which you are not familiar, first check your state’s list of invasive species to determine if a plant has been declared invasive or a species of concern, or if it is on a watch list. Avoid planting all such plants and look for native alternatives. Many invasive plants were commonly used in gardens and municipal plantings before their detrimental effects were understood. (And some are still being sold in the trade, so beware.)

Naturalized Plants

A naturalized plant is a nonnative plant that can reproduce and maintain itself over time without human help. Even with time, though, naturalized plants do not become native members of the local plant community. Invasive plants are a subcategory of naturalized plants, and those are the ones you really need to eliminate.

Naturalized plants are best avoided in your landscape. Some naturalized plants may become problematic in the future if they disrupt ecosystems, displacing native plants that would otherwise be present. If you want plants that spread, choose native plants that have this trait.

Invasive Plants

An invasive plant is a plant that is nonnative, is able to establish on many sites, grows quickly, and spreads to the point of disrupting ecosystems. However, not every plant with an aggressive growth habit is an invasive plant, as even some native plants can be aggressive, and this can be useful in certain garden situations.

Invasive plants, such as kudzu, choke out native plants and eliminate native habitat.

The U.S. Government defines invasive species as species nonnative to the ecosystem under consideration and whose introduction causes, or is likely to cause, economic harm, environmental harm, or harm to human health. Plants that are invasive in one part of the United States may not be problematic, at least for the time being, in another part of the United States. Common invasive plants in the Northeast include Japanese barberry, oriental bittersweet, Norway maple, and Japanese honeysuckle. Common invasive plants in California include black acacia, giant reed, Mexican feathergrass, and tree of heaven.

Many plants that have become invasive over time were actually introduced through horticulture long before there was any suspicion that these plants could cause problems outside of their native range. Most states in the United States have their own invasive species list. Do not plant those plants, and remove any you may already have. Also avoid plants listed as species of concern but that are not yet defined as invasive.

Native coneflower (Echinacea purpurea): A great choice for pollinators.

Plants to Leave Out

When considering plants for your Pollinator Victory Garden, start with the easy decisions about plants that should be left out. You will likely see many of these plants in other gardens—but don’t you make the same mistake. Following are the three groups of plants you can eliminate or minimize for pollinators.

More on Choosing Plants: Straight Species, Cultivars, and Hybrids

When you go plant shopping, labels and plant names can be confusing—and you may not always be sure of what you are buying. If you know the differences in how plants have been propagated or bred you can make the best choices for pollinators.

Fritillary butterfly nectaring on butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Behind every successful Pollinator Victory Garden are plants that have the characteristics that attract pollinators and deliver the resources they need. A flowering plant that has little or no nectar or pollen may be beautiful, but it has little value in a pollinator garden. A plant that is cultivated for its peculiar flower color or other significant deviation from the species may not be recognized by the pollinators you are trying to attract. Mother Nature really does know best—follow her lead when choosing plants.

Botanical Names

With regard to plant names, the only way to truly identify a plant is to use its botanical name. Those of us who suffered through Latin classes in school can finally put some of that education to good use. Common names for plants are not always helpful, as they can vary significantly from country to country, state to state, and region to region. Latin is your friend when it comes to plants because it ensures that you get exactly the plants you want.

Botanical names consist of two words in Latin. The first word, always capitalized and italicized, is the genus; the second word, always lowercase and italicized, is the specific epithet. The two words together form a plant’s name, also known as the plant species. Asclepias tuberosa is an example of a plant species. This particular plant has myriad common names, including butterfly weed, butterfly milkweed, pleurisy root, orange milkweed, chigger flower, fluxroot, and orange root. Botanical Latin makes it clear, no matter where you live, what a given plant really is.

As plant DNA analysis becomes more sophisticated, botanical names sometimes change. Plant taxonomists (the folks who identify, describe, classify, and name plants) may rename a plant to better align with its true lineage and relationship to other plants. This makes complete sense—until you go to a garden center looking for Aster laevis (smooth aster) and can only find Symphyotrichum laeve, the new botanical name for the same plant. But, growers, nurseries, and garden centers are not always consistent about using new names on plant tags. Go plant shopping armed with both old and new botanical names!

Plant Choices

Genetic diversity of plants within a species is also important for ecological health, but not all available plant choices offer this diversity. As with most things, there are trade-offs when making plant choices. Go to the garden center armed with the information you need!

This means understanding the differences between straight species plants, cultivars, and hybrids. From an ecological perspective, straight species plants offer the greatest biodiversity and the biggest ecological impact, both important factors for healing our challenged environment. Here is a look at the differences between the three types.

Straight Species Plants

A straight species plant is one that occurs naturally without breeding or hybridization. “Open-pollinated” plants grown from seed have the greatest genetic diversity. Give a preference to regional, straight species native plants that are open pollinated (meaning, naturally pollinated by insects, wind, or water) for their boost to biodiversity and their adaptation to the local region.

Phlox paniculata ‘Jeana’, a nativar of garden phlox that is a clone. It does attract many butterflies and moths.

An example of a straight species plant is Penstemon hirsutus (hairy penstemon). Some plants may have a naturally occurring subspecies or variation of the plant, such as Penstemon hirsutus var. pygmaeus, a dwarf form of this species. You may also see a subspecies of a plant designated as “ssp.”

Cultivars and Nativars

A cultivar is a cultivated variety of a plant, often selected for a desired trait, such as pest or disease resistance, flower color, fruit color, foliage color, habit, size, and so on. A cultivar may be propagated by seed or by vegetative cutting (resulting in a genetic clone). Cultivars are designated by single quotes—for example, Echinacea purpurea ‘Magnus’. A cultivar name is not italicized.

A nativar is simply a cultivar of a native plant. Unfortunately, this is often the only type of “native” plant available at nurseries. Nativars are somewhat controversial since they have less genetic diversity and potentially have some loss of ecological function compared to straight species plants.

Many nativars are genetic clones that have been propagated from cuttings, while others are open-pollinated and grown from seed. Clones are just what you imagine—think Dolly the sheep—and they lack genetic diversity. Plant labels typically do not disclose whether a plant has been grown from seed or from a cutting. Do a little digging online when buying plants.

In terms of an ecological best bang for the buck with the most biodiversity, straight species plants are first choice, open-pollinated nativars are next best, and cloned nativars come in third.

Hybrids

Hybrid is a word that often refers to the intentional breeding of two different plant species to create a new plant. Hybrids are designated by the absence of the second Latin word in a plant’s name (its specific epithet) or the presence of an “x” symbol. For example, Baptisia ‘Purple Smoke’ is a hybrid of Baptisia alba (white wild indigo) and Baptisia australis (blue false indigo). Hybrids are controversial in the world of native gardening due to their loss of genetic diversity, although some natural hybrids do occur without human intervention. Some hybrids, but not all, are also sterile. In a Pollinator Victory Garden, hybrids are not the best choice.

Plant Selection Tools and Tips

Proper plant selection is key for any garden including a Pollinator Victory Garden. For best plant health, pollinator support, and positive ecological impact, emphasize plants that are native to your local area and appropriate for your landscape conditions.

Stay Local

Plants form the basis for local ecosystems and have evolutionary connections to an area’s wildlife, including pollinators. Yes, generalist native pollinators may nectar on nonnative plants and nonnative honey bees may sip nectar from native plants, but ecosystems are complex and the depth and extent of evolutionary connections and ecological functions may not always be obvious. Native nectar plants that also function as larval host plants are an example of these complex evolutionary connections.

For best success, plant native plants that native pollinators have evolved with in your area. Look for locally grown native plants or seeds when shopping. As a bonus, native plants will boost the overall ecological health of your landscape. Don’t worry if you also want to support honey bees; many native plants will feed these generalist pollinators too.

Match Plants to Landscape Conditions

The old saying “Plant the right plant in the right place” was likely coined by a gardener who learned the hard way. This pithy phrase is often followed by the consoling adage “You don’t know a plant until you’ve killed it.” Better to plant the right plant in the right place to begin with! No matter how fantastic a pollinator plant is, if it is not appropriate for your landscape conditions, don’t plant it. It’s just a matter of time before a plant that requires full sun and fast-draining soil will fail when it’s planted in a shady garden with soggy clay soil. Research any plant you are considering for your pollinator garden to determine if it is suitable for your own landscape conditions. There are many good resources noted in the appendix of this book to help you research plants.

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana), a native plant that is a larval host and a good nectar plant.

Understand Plant Regionality

Regional plant lists can be a helpful starting point when selecting plants for your Pollinator Victory Garden. But the way regions are defined can vary based on the source. As a start, see if your state is included in the region being discussed.

Goldenrod (Solidago species) is an important source of late-season nectar.

Don’t be surprised if you see the same plant genus (collective name for a group of related plants) occurring in multiple regions of North America. For example, the genus Solidago (goldenrod) is found in every region of the United States, accounting for more than 100 species. But not every species of goldenrod occurs in every region or in the same geographic conditions. Some species have very large ranges and are adapted to a variety of ecological regions (ecoregions). Solidago altissima (tall goldenrod) has a wide range and is found in most regions of the United States. Other goldenrod species have extremely limited ranges—for example, Solidago albopilosa (whitehair goldenrod) is found only in Kentucky.

Because the geography, ecology, and growing conditions can be very different within a particular state or region, not every plant listed for that state or region is suitable for every landscape. Gardening in California underscores this point. California’s ecoregions vary tremendously and range from hot, dry desert areas to mountainous regions at high elevations. The native plants that occur naturally in these areas are very different and so are the plant choices for a pollinator garden located within each locale.

Refer to Regional Plant Lists

As a bonus to this book, pollinator plant lists by region are provided at www.ecobeneficial.com/PVG. Each regional list covers several states, or one large state in the case of California. Use your regional list as a starting point when selecting plants; there will be variations in species within a given region depending on the geographical conditions of the ecoregion. If you are interested in the nitty-gritty of ecoregions, visit the EPA website on Ecoregions at www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions.

Some plant groups make the list for every region in the United States. Milkweeds (Asclepias species) are found in each region, with approximately eighty native species in the United States. As with any plant genus, not every milkweed species will work in your garden. Your best milkweed choices depend on your location and landscape conditions.

In California alone, fifteen native species of milkweed with varying geographic adaptations are found. Asclepias erosa (desert milkweed) occurs only in desert areas with dry, sandy soil, while Asclepias speciosa (showy milkweed) is typically found in mountainous areas where soils are seasonally moist. Neither plant will succeed in the other’s landscape conditions.

Plant regional milkweeds and avoid growing nonnative tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) that can promote a parasite on monarchs, as well as reduce migration success and overall health. For an extensive explanation of this subject, please visit The Xerces Society website, www.xerces.org.

Fine-Tune Your Pollinator Plant List

Your regional plant list at www.ecobeneficial.com/PVG is just a starting point; use it in combination with the other resources recommended here to fine-tune the best plants for your pollinator garden.

Visit the websites of your state and regional native plant societies; these organizations often post native plant lists or provide a searchable database. The Native Plant Society of New Jersey publishes plant lists for every county in the state. The New York Flora Atlas, run by the New York Flora Association, enables users to search native plants by county. The Calscape website, run by the California Native Plant Society, allows users to search plants that are native to their exact street address.

If no county-specific database exists for your area, try using the plant database of the Biota of North America Program, which covers all states down to the county level. The USDA PLANTS database is also useful, providing range maps of native plants that can be magnified to the county level.

Several nonprofit organizations publish pollinator plant lists on their websites, including the Xerces Society, the Pollinator Partnership, and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Society (a good resource for researching native plants of all types, by state).

Buy Native Plants Locally

Local native nurseries are often the best sources for native plants. In a perfect scenario, the native plants offered will be straight species, grown from seed that has been collected locally, ensuring that the plants will be adapted to regional conditions, genetically appropriate, and genetically diverse. Also on the wish list are plants that have been grown in real soil (not a soilless mix) free of synthetic chemicals, and certainly kept pesticide free. Plants with such provenance can be hard to come by. Be willing to pay more for them as they cost more to grow.

Seasonal native plant sales organized by nonprofit organizations, which have become quite popular, usually occur in the spring and fall. Check with your local native plant society, Audubon chapter, Sierra Club chapter, Master Gardener group, and other environmental organizations to see if native plant sales are scheduled in your area. Knowledgeable volunteers usually staff these sales and will provide you with personal shopping help and advice at no charge.

Local garden centers and nurseries may also be a source for native plants. If they don’t carry natives yet, ask them to do so. Wherever you buy your plants, insist that they are free of systemic pesticides. Big-box stores have gotten the message that neonicotinoids, a class of systemic pesticides, are politically and ecologically incorrect. If you buy from big-box stores, check the plant labels to make sure that the plants are labeled “neonic-free.”

Guidelines for Planting Foraging Habitat

As is the case with all planting, planting the right plant in the right place ensures gardening success. Using native plants that have evolved with the pollinators you want to attract will give your foraging habitat an advantage over gardens planted with nonnative species.

Varied flowers feed a diversity of pollinators.

There are no hard-and-fast rules that dictate the perfect foraging habitat, nor can every site accommodate every planting goal, but below are some general guidelines.

Where to Plant Forage for Pollinators

Almost any part of a landscape can be used to grow flowers for pollinators, but not all sites are equally valuable as foraging habitat. You will obviously be limited by the size of your landscape and the general conditions within it. If you are lucky enough to have parts of your landscape in full sun, you have an advantage. But even if you don’t have a sunny spot, you can still plant forage plants.

Pollinators prefer sunny gardens.

Determining the Size of a Foraging Habitat

When deciding on the size of an area to plant with forage plants, go as large as you can but perhaps do so in multiple steps. If you are working with a landscaper, the work can be accomplished more easily than if you are planting the area yourself. Be realistic about your time, energy, and budget, and the scale of the project. Splitting a landscape into a series of smaller projects can be easier than doing everything at once; you can connect pollinator patches as you create them. Even if you have a very small landscape such as an urban garden or just a terrace or patio, any pollinator habitat you create is valuable, including a container garden filled with flowering native perennials.

Sunny Areas

Most forage plants, and most of their respective pollinators, prefer sunny conditions and open areas. The warmth of the sun enables cold-blooded pollinating insects to be active, and the ability to see the sky allows them to navigate. If your landscape has both sun and shade, emphasize planting most of the foraging habitat in sunny areas. An obvious area that’s usually in a sunny, open location is the lawn. Convert any part of the lawn you can live without into a flower-filled pollinator buffet. It’s fine to keep lawn that you really use, but lose the rest, making sure to maintain it pesticide free.

Hard-to-mow areas, like hillsides (especially if they’re sunny), can be a boon to pollinators (and the person who has to mow) when they’re converted into expanses of flowering ground covers; thicket-forming, short, flowering shrubs; or even diminutive meadows.

Shady Areas

Don’t despair if your landscape is devoid of sun; you can still plant for pollinators, but your plant selections will be different. Numerous pollinator-friendly plants grow in part shade or even full shade. Shade plants can be valuable to pollinators, especially when not much else is around. In the northeastern United States, spring-blooming woodland plants including Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria), trout lilly (Erythronium americanum), and spotted geranium (Geranium maculatum) are critical to early-emerging pollinators such as bumble bees and may be the only floral resources around when pollinators need them. Even summer-blooming plants like Joe Pye weed and fall-blooming shade plants can have value to hungry pollinators. Woodland asters and goldenrod (Eurybia divariacta, Symphyotrichum cordifolium, Solidago caesia, Solidago flexicaulis, and others) receive many pollinator visitors in fall.

Shady gardens can attract pollinators, too.

Flower Power in the Pollinator Victory Garden

Flowers are the most important food sources for pollinators, but there’s more to it than planting flowers and waiting for pollinators to appear. A successful Pollinator Victory Garden achieves a balance between two seemingly disparate principles: plant diversity and plant sufficiency. This can be thought of as “achieving floral balance.” Your garden needs to have a wide variety of plant species in place to meet the varying needs of different pollinators throughout the growing season. At the same time, there must be enough of each species to entice and feed all of the pollinators that use them. It can be tricky to figure out this balance, especially in smaller landscapes. There is no perfect formula, but by keeping these concepts in mind and knowing which regional pollinators could be attracted to your landscape, you can make your garden a valuable resource.

Diverse plantings increase the number of pollinator species you can attract.

If you keep European honey bees or if managed hives are located nearby, there will be increased competition with native bees for floral resources. While not all bee species use the same flowers, generalist foragers will use many of the same plants. In the presence of large colonies of honey bees, ramp up your floral resources, meaning: plant a lot more flowering plants. Plant sufficiency is also especially important in developed neighborhoods where fewer landscapes are planted for pollinators.

Boosting Plant Diversity

Diversity is critical to healthy ecosystems. Scientists have learned that landscapes planted with many different plant species are more resistant to pests and diseases and to the effects of climate change. We face all three of those significant challenges in our landscapes. The traditional gardening practice of massing huge swaths of the same species of plant may look dramatic, but from an ecological perspective, it is unwise. Balance is key when massing plants for pollinators or we lose diversity.

By planting many different species of plants in a landscape, you’ll have a better chance of attracting a greater diversity of pollinators. With an estimated 200,000 species of pollinators around the world, including 20,000 bee species, any landscape planted in an ecologically sound manner may be able to attract and support hundreds of different pollinator species and thousands of different pollinators.

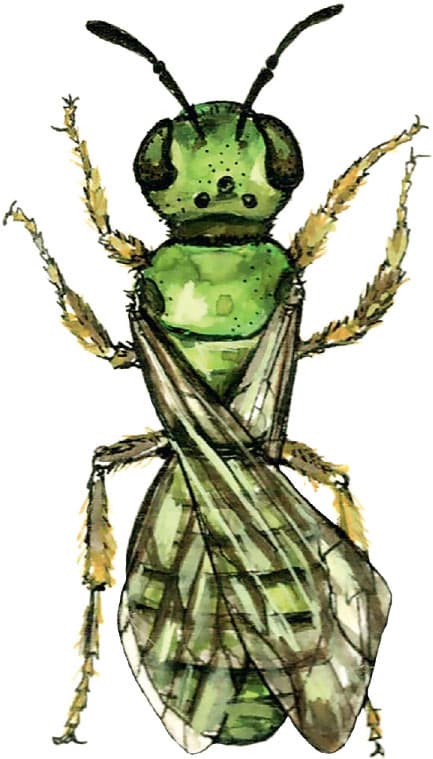

Not every pollinator is attracted to or can use the same species of plants. A long-tongued bee can access nectar from a long tubular flower, such as a larkspur, but a short-tongued bee cannot. Bees with shorter tongues appreciate more open flowers in a garden, particularly flowers with small nectaries (where the nectar lies within a flower). Generalist foragers can use a much greater variety of plants than specialist foragers, so plant for both. Our pollinator gardens should feed many different pollinator species, and that requires having plant diversity.

Achieving Plant Sufficiency

There is a counterpoint to planting diversely. To successfully attract pollinators, you must also plant sufficiently, making it easy for pollinators to find the flowers you are offering and to provide enough of that particular resource. Plant sufficiency, or enough floral biomass, is crucial to feeding all of the various pollinators that may visit your landscape. Remember, if honey bees are nearby, their large colonies require a lot of floral food to survive.

Floral targets help pollinators forage (Coreopsis verticillata).

The behavior of floral constancy in many bees and butterflies underscores the need for planting enough plants of the same species. These pollinators forage many times a day, but each time they forage, they look for one species of plant. Planting a single specimen of a perennial will not do the job for them. Think like a bee or butterfly when you go plant shopping; a pollinator needs a full meal, not just a few morsels.

There are two basic gardening approaches to provide plant sufficiency. One is to create pollinator targets and the other is to create plant repetition. Both approaches can be used in most landscapes except for very small spaces, such as a balcony or a diminutive patio garden.

Planting pollinator targets

Pollinator targets are groupings of the same species of plant, which allow pollinators to find the nectar and pollen they need easily. The achievable size for each target in your garden will depend on the size of your landscape. In a landscape with plenty of room for many different species, a target 3 feet (0.28 m) square of the same plant species, for every species, may be a reasonable goal. Realistically, not every garden has the room to achieve this goal. There will always be a trade-off between planting diversely and planting sufficiently, so just do the best you can with the space you have.

Plant repetition of a meadowscape

While most individual trees and shrubs offer significant pollinator targets when in bloom, the majority of perennials need some companions. When shopping for flowering perennials, choose at least three plants of the same species. A single, lonely plant of small size can get lost in the garden and will be harder for a pollinator to find. If you don’t have the space to include sizeable targets for each plant species, consider repeating a plant throughout your landscape.

Incorporating plant repetition

Plant repetition is a technique that can be used with pollinator targets or as a stand-alone method in a landscape. With this approach, a single plant species is repeated throughout the garden no matter the size of the landscape. A European honey bee might make fifty foraging trips in a day. She will happily find the repeating plants throughout your garden.

Not every pollinator finds flowers the same way. A compromise approach in smaller gardens is to repeat small groupings of the same plant species throughout the landscape, ensuring that all pollinators can find what they need.

One method of plant repetition, which is particularly useful where browsing deer are a problem, is to create a meadow or a meadowscape (a meadowlike garden). Natural meadows have irregular, recurring patterns of flowers, offering pollinators nectar and pollen while eliminating the easy “deer buffet” that many of our gardens have become. Learn more about meadowscapes in chapter 5.

Planning for Succession and Overlap of Bloom

It’s very common to see gardens that have a flush of bloom at a certain time or two of the year and then offer few, if any, flowers for pollinators during the rest of the growing season. Think of all the pollinators that go hungry when nothing is in bloom! Plant for a succession of bloom throughout the growing season and your pollinators will thank you. Include a variety of blooms that appeal to different types of pollinators to feed many different species and include plants with overlapping bloom times to ensure nectar is available.

Red maple flowers (Acer rubrum) are early sources of forage.

The first step toward achieving these goals is to record the plants you already have in your garden, and when they bloom. Take a bloom inventory of flowering trees, shrubs, and perennials (but do not include any double-flowered plants). If you cannot do this from memory, fill in the blanks as flowers appear. You can be as specific with days as you like or simplify the process by using time ranges such as early spring, midspring, late spring, and so on.

To create a bloom inventory chart, record all flowering plants in your garden, as in the example below.

By taking a bloom inventory, you will be able to determine when the gaps in flowering occur or when there are times of minimal bloom; these are the critical times to plant for. Create an ongoing pollinator buffet filled with choices for all types of pollinators.

Very early-blooming plants are not always considered in a pollinator garden, but they are important. Bumble bees and honey bees can forage in chillier weather than some other bee species and can be active very early in the spring. Make sure to have early-flowering native plants when these insects emerge from a cold winter. A red maple blooming in March or a serviceberry blooming in April may be early feasts for honey bees and other early bees, while squirrel corn or Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra species) may be critical early foods for a bumble bee queen who needs to establish her new colony.

Continue the flower show until the end of the growing season, which for many regions is late fall. Quite a few pollinators are still active at that time and benefit from native plants like goldenrod and asters. Late-season blooms are often forgotten in gardens. Add them to your Pollinator Victory Garden to feed mated female bees preparing to overwinter, monarchs setting off for their migration, and hummingbirds fueling up before their long flight south.

When choosing plants, consider that not all plants have the same duration of bloom. But don’t just plant those species that seem to have an endless bloom. In early spring, a serviceberry (Amelanchier species) may bloom for just a week or so, or even less if it rains a lot. In contrast, a purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) has a very long period of bloom, often lasting for many weeks. This, however, does not make the serviceberry a bad pollinator plant compared to a coneflower. The serviceberry flowers early in the season when not much else is around to provide nectar. It’s an important food source for early emerging mining bees and sweat bees as well as a larval host plant. Duration of bloom is not the sole factor when choosing pollinator plants.

Serviceberries (Amelanchier species) offer early blooms for pollinators.

It can take some time to establish a consistent succession of bloom in a pollinator garden, but your observation and planting will pay off.

Planting to Attract Different Types of Pollinators

Pollinators and plants have coevolved so that both parties benefit. Through evolution, pollinators adapt to certain flower traits and vice versa, ensuring that the pollinator gets the food it needs while the plant is successfully pollinated and can reproduce. These evolutionary flower traits are called pollination syndromes. Flower color, aroma, structure, and amount of nectar, the location and quality of pollen, and the presence or absence of nectar guides are all traits that determine which pollinator is likely to use a given flower.

Scarlet bee balm (Monarda didyma), a hummingbird favorite

Exceptions to these pollination syndromes do occur, especially in the absence of choice for a pollinator. Although hummingbirds prefer red, deep tubular flowers, such as those of scarlet bee balm (Monarda didyma), they will also use flowers without these characteristics. But why not make it easy for them and give them the flowers they prefer? While you may be tempted to purchase a yellow cultivar of coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens), hummingbirds may be happier with the straight species, which sports orange-red tubular flowers accented by yellow throats. Knowing the flower traits each type of pollinator has evolved with will help you make better plant choices and create a more compelling pollinator garden.

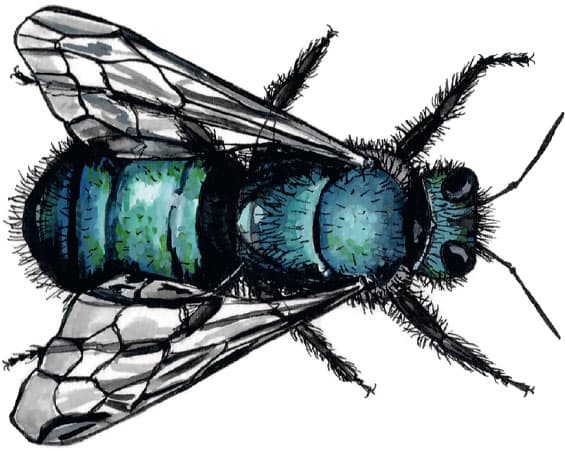

Although preferences for some flower characteristics do overlap from pollinator to pollinator, others do not. A strong, sweet fragrance emanating from a flower will not entice birds, which have no sense of smell. If that fragrance occurs at night, it will often be irresistible to nocturnal moths looking for a meal. A fresh and mild floral scent will appeal to bees, while it often takes a foul-smelling flower to attract pollinating flies. Nectar guides on flower petals will attract both bees and butterflies but they won’t be noticed by a pollinating beetle. Consider these traits (pollinator syndromes) when selecting plants for pollinators.

Remember that the more flower traits you include in your garden, the wider the array of pollinators you will attract.

Food for Butterflies and Moths: Larval Host Plants

Flowers are arguably the best known and most important source of food for pollinators, but for butterflies and moths, nonfloral foods called larval host plants are critically important and cannot be left out of a discussion about food for pollinators. Butterflies and moths undergo complete metamorphosis, meaning they have four distinct life stages: egg, caterpillar (larva), pupa (chrysalis), and adult (imago). While the majority of adult butterflies and moths eat nectar, the preponderance of their caterpillars have a completely different diet.

When planting a garden, we may not have considered what caterpillars eat, but it is extremely important for supporting butterflies and moths. Most caterpillars eat plant parts, typically leaves from larval host plants, specific plants with which the caterpillars have evolved. Some caterpillar species eat flower buds and flower parts, fruits, seeds, other caterpillars, or even animal feces. But by and large, caterpillars eat leaves of their larval host plants.

Types of host plants

Host plants can be trees, shrubs, vines, perennials, grasses, or sedges—it depends on the caterpillar species in question. Trees and shrubs are particularly important host plants—many, but not all, native woody plants serve as larval hosts. Some species can sustain hundreds of different caterpillar species. Research conducted by Dr. Douglas Tallamy, author and professor at the University of Delaware, concluded that in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, native oaks as host plants support more caterpillar species than any other trees or shrubs: 557 total caterpillar species. Native cherries and willows are close behind, feeding 456 and 455 caterpillar species respectively.

Although it may be easy to see where adult butterflies are nectaring, it can be much harder to discern where their caterpillars are feeding. Since most moths are nocturnal feeders, their larval food plants can be even more difficult to determine by observation. Your best tools to determine the host plants that feed specific caterpillars are in-depth books and credible websites on caterpillars, butterflies, and moths. Also check out the resources in the appendix of this book and the list of common host plants and the caterpillars they feed, available at www.ecobeneficial.com/PVG.

Spicebush swallowtail butterfly caterpillar eating the leaves of one of its host plants, spicebush (Lindera benzoin)

Adding host plants

If you have a very small garden without enough room to plant a variety of host plants, you can “borrow” or “share” host plants with neighbors. Talk with your neighbors to form a plan to fill in the host plant gaps in order to attract more butterflies and moths.

To make sure that you have the right larval host plants available, create a host plant checklist for your landscape. The first step is to determine the butterfly and moth species that are common to your area. There are online and printed resources to help you (see the appendix). Set up a simple checklist to note the host plants you already have in your garden that regional butterflies and moths look for. Don’t have enough host plants in your garden? Then it’s time to plant more.

From the sample checklist above, you could determine whether your existing garden can support either butterfly in question. By conducting this brief exercise, you would also discover that several plants (in bold) will feed multiple species of caterpillars found in your region that you want to support. This preplanting exercise can save you time, money, and planting space and feed more types of caterpillars.

Host plants and evolutionary connections

Adult moths and butterflies have evolved to instinctively sense where to lay their eggs (oviposit) on or near the larval host plants appropriate for their particular species. This is one reason native plants are so important in a pollinator garden, because native pollinators and native plants have evolved together. When the eggs hatch, caterpillars first eat their own eggshells and then have an immediate food supply nearby from their host plant. While some butterflies and moths have evolved to be able to depend upon a wide range of larval host plants, others have a very limited diet; the monarch may be the best-known example of the latter.

Monarch butterflies have evolved to use plants in the milkweed group (the genus Asclepias) as host plants. Although adult monarchs will sip nectar from many different flower species, including milkweeds, their caterpillars eat only milkweed leaves. If you want to support monarchs, which have declined by at least 70 percent since their population high in the 1990s, include milkweeds in your pollinator habitat. Native milkweeds are also excellent nectar plants for a variety of pollinators.

Tolerating plant damage

For many homeowners, the idea of encouraging the chewing of plant leaves may be a bit hard to accept, but that is what most caterpillars do. Sometimes the leaf chewing by caterpillars appears quite minor, while at other times it may be more extensive. Caterpillars must eat a lot to grow; a newly hatched caterpillar may increase its body mass 10,000-fold in just two weeks. If you want butterflies and moths, accepting leaf damage is part of the equation. It will be worth it when you see adult butterflies flourishing in your landscape.

A proud client once pointed out her leafless milkweed plants happily exclaiming that she had raised an abundance of monarchs that year with the milkweed we had planted in her garden. Further evidence was the bevy of adult monarch butterflies busily nectaring on other flowering plants around us. Becoming a pollinator steward means expanding the definition of what a garden can be, which is a healthy ecosystem where some plant damage is perfectly acceptable for the greater good.

Adding Biomass with Trees and Shrubs

While flowering perennials are typically the mainstay of a pollinator habitat, don’t forget their woody friends: flowering trees and shrubs. These woody wonders have a particular appeal as pollinator plants with an abundance of blooms on a single plant. Flowering trees and shrubs of size can ramp up your pollinator foraging resources, which is particularly valuable for large colonies of honey bees. Trees, shrubs, and vines are often overlooked as pollinator plants, and that’s a shame. For example, red maple (Acer rubrum) flowers are one of the earliest sources of nectar and pollen for bees in the northeastern United States, making that tree a valuable addition to a pollinator garden in that region.

Redbud (Cercis canadensis), an early pollinator favorite

Small trees and shrubs can be used as foundation plantings against a house, combined diversely as a hedgerow for pollinators, or planted wherever they fit into your landscape. They can even be planted around the edges of a dedicated pollinator garden as long as they don’t shade out the open, sunny areas. Determine the mature height and width of a plant before you plant it so you don’t create a shade garden later.

Incorporating Nonfloral Foods for Pollinators

Not all pollinators get their complete nutrition from flowers. A number of nonfloral foods are eaten by pollinators, depending on the pollinator species. In the case of butterflies, mourning cloaks, question marks, eastern commas, and red admirals favor tree sap, rotting fruit, aphid honeydew (aphids’ liquid excrement), bird droppings, and animal feces. Even carrion can be enticing to some butterflies. In North America, there is one type of carnivorous butterfly, the harvester, that specializes in eating woolly aphids.

Hummingbirds mostly eat nectar, but they also feed on tree sap and juices from overripe fruits. For protein, they eat pollen and small insects. Pollinating bats feed on insects as well as nectar, pollen, and flower parts, depending on the bat species.

Providing these alternative food sources is best done by maintaining a healthy and well-balanced ecosystem. Include a few sap-producing trees, some fruit-bearing trees and shrubs, and quality habitat for birds (bird droppings!), and avoid the use of pesticides. In a pollinator garden, aphids actually have value, because they produce honeydew for butterflies and a protein snack for lady beetle larvae (which, conversely, keep aphid populations in check).

A Man-Made Butterfly Buffet

If you want to supplement natural foods, you can create a butterfly buffet of rotting fruit. Fill a plate with overripe fruit and suspend it from a tree with thin cord or fishing line to protect it from hungry mammals. Leave it out only on sunny days when butterflies are active or leave it out at night for nocturnal moths to feed on. Just place the dish where you can easily clean and replenish it.

Hummingbird Feeders

Hummingbirds appreciate a hummingbird feeder in addition to flower nectar, if the contents of the feeder are replaced frequently and the feeder is kept clean. Glass feeders are easier than plastic ones to clean thoroughly. Skip the red dye, which may not be safe, and stick to the standard formula of one part water to four parts sugar, boiled together to form a sugar mixture. You’ll also save hummingbirds from expending valuable energy if you provide a feeder that has places to perch while the hummingbird nectars.

Puddling

In nature, butterflies often gather at moist, sandy, or gravelly spots and use their tongues to suck up moisture containing salts and minerals. This behavior, called puddling, is mostly seen in male butterflies. There is speculation as to why butterflies do this; it may be that they need additional sources of sodium and minerals beyond what they get in nectar.

This sodium deficiency may be more severe in male butterflies during mating, potentially explaining why the majority of puddlers are male. It has also been speculated that males use puddling as a way to incorporate nutrients into their sperm, which is then transferred to the female during mating, as a way of increasing egg viability.

Although it is not clear what puddling behavior really represents, it seems to be important, at least for males. Notably, butterflies also feed on animal dung, urine, sweat, and carrion, which are possibly other ways to obtain sodium.

You can create a puddling habitat in your landscape by filling a large clay saucer with coarse sand, gravel, and/or mud and topping it off with water to make a damp mix. Add a dash of finished leaf or manure compost along with a sprinkle of salt to boost the nutrients. Keep the mixture consistently moist and occasionally replenish the added nutrients. Don’t be disappointed if butterflies don’t show up; it can be hit-or-miss with a homemade puddle. The easiest approach is to leave existing puddling sites undisturbed, perhaps adding moisture when needed to prevent them from drying up.

Butterflies puddling

Insect Meals

Some pollinators, including hummingbirds, bats, and wasps, have a varied diet that includes insects.

A healthy pollinator garden is filled with many different types of insects, which are an important source of protein. Sometimes pollinators wind up being that protein source for a hungry bird. Just remember your garden is an interconnected food web, and all creatures have to eat.