Part 2

10 presenting skills in action

Skill 1 Presenting to sell a product

Skill 2 Presenting a concept or idea

Skill 3 Presenting to motivate and inspire

Skill 5 Presenting a team brief

Skill 6 Presenting a new project

Skill 7 Presenting at a meeting

Skill 8 Presenting on a conference call or webinar

Skill 10 Presenting in 5 minutes

This part focuses on providing specific tips for particular presentation situations that you might find yourself in. It is intended to be a reference guide, to dip in and out of as you see fit.

Skill 1

Presenting to sell a product

If selling a product is the purpose of your presentation, it is very easy to focus on all the good things your product offers and present these to make an apparently compelling case for your potential customer to say ‘yes’. This is the most common mistake I see people make when presenting a sales pitch. All the positive information is downloaded in one long spiel, leaving the potential customer bamboozled and overwhelmed by lots of data, facts, figures and features of the product. When faced with this much information it is much easier to say ‘no’, or ‘not yet’, rather than ask detailed questions that risk another download of information.

To help avoid this pitfall, there are particular things to keep in mind. You will, of course, need to research your customer. (For more on this see Step 2, which covers understanding and connecting with your audience.) This skill looks at the following:

- Is there a downside to your product?

- The benefits of using ‘but’ to present the downside.

- Why you should not list all the features.

- How to make your product FAB.

Is there a downside?

First of all, does your product have a downside? Yes, strange as it may seem, I’m asking you to consider the negative features of your product. Why might your potential customer object to making a purchase? Maybe the product can be bought cheaper elsewhere, has a long lead time for production or doesn’t meet the exact specifications.

If there is a downside your potential customer is likely to know it. They will be waiting to challenge you with that information. Marketing and psychology professor Robert Cialdini’s work on influencing (www.influenceatwork.com) shows that it is better to present the downside first. His research has shown that presenting the problems first reinforces credibility and honesty. Be the first to include the downside in your presentation rather than wait for the customer to mention it.

The benefits of using ‘but’ to present the downside

L’Oréal use ‘but’ beautifully in their advertising strapline ‘expensive, but you’re worth it’. They admit their product is expensive. Cialdini’s research has shown that following the downside with a ‘but’ helps to alleviate the issue psychologically. This is because ‘but’ tends to negate the words that precede it.

You might consider saying:

- ‘It’s a long lead time, but worth the wait for the bespoke product.’

- ‘It’s not the cheapest on the market, but it is (one of) the best.’

- ‘It doesn’t meet your exact specification, but it does ABC, which provides the same results.’

Don’t list all the features, focus on the benefits

Having got the downside out of the way at the start of your presentation, you can focus on the sell. But don’t tell your potential customer every single feature your product has to offer.

Why not? There are probably a large number you can list, and going through every one of them is going to bore your potential customer, at best. It is much better to ask the customer what they are interested in first and choose the features and specific benefits that relate to their situation.

The best way to make an effective sales pitch is to do your homework on the product and the customer. Make some guesses as to their needs, likely objections and the margin you can afford to give. On the day of the presentation, make it interactive by asking your potential customer what specifically they are looking for. What will they be using your widget for? What are the circumstances? What situations will the widget need to perform under, e.g. temperature, pressure, etc.? How many will they need?

By asking questions you will be able to decide which are the relevant features and benefits to mention. It will also engage your potential customer as they are involved in a discussion, not listening to you reel off a list.

Some questions to consider asking are:

- What problem is your potential customer encountering (which your product might solve)?

- How big is the problem? If it remains unsolved, what impact would that have?

- If your product could remove the problem, what benefit would arise?

How to make your product FAB

When running sales workshops in my past employed life, we used the mnemonic FAB to help identify whether and how a product would suit a customer:

- Features;

- Advantages; and

- Benefits.

For example, a glass bottle may have many features:

- Clear – advantage is you can see the contents

- Size – advantage is capacity of one litre of liquid

- Cap – screw-top lid, advantage is it’s resealable

- Label – advantage of being customised to the customer’s requirements

- Eco – made from recycled glass and advantage of being recyclable.

But if your customer has arthritis and is looking for something that won’t break when dropped, then no matter how you pitch it, your product won’t sell, because the customer cares about advantages and benefits to them, not the generic features.

![]() To sell your product, look at it from the customer’s point of view.

To sell your product, look at it from the customer’s point of view.

![]() To understand the customer’s needs, ask questions.

To understand the customer’s needs, ask questions.

Skill 2

Presenting a concept or idea

The challenge with presenting a concept or an idea is that these things are intangible; there is nothing for people to see, to take hold of or to smell.

The first consideration when making the intangible accessible to the listener is to use examples to bring your idea to life. Find stories, similar situations or universal experiences that can make it real and accessible in the mind of the listener.

Using stories

Stories are a great way of accessing people’s emotions. They bring situations into the heart and away from the head; indeed, the heart is often where decisions are made, which are then backed up by the head.

I wonder how many readers will remember the days before YouTube, before CDs, before Dropbox, when information was shared through cassette tapes. Have you ever experienced the frustration of not being able to skip through the tape to the part you wanted to listen to? In those days you had to wind your way through the cassette, not knowing where the key information was – there was no easy way to skip to the interesting sections. Sometimes the tapes would get tangled by the player and be unusable.

You will, I’m sure, have watched a video on YouTube. You can see how long it is; at a click you can jump sections; and you can watch it again and again should you so choose, without having to rewind the cassette.

In business, life is sometimes more like the cassette than YouTube. Sometimes you don’t know where you are, how people will respond or which bits will be interesting. You often have to go through the whole process to find out.

I have a collection of cassette tapes on the shelves at home from a story-theatre workshop by Doug Stevenson, creator of the Story Theatre Method for storytelling in business. This was in the days before YouTube and CDs. But thanks to modern technology you will be able to watch Doug give a taster of his storytelling skills by clicking on www.youtube.com/watch?v=YUYyaXFO0FY and listening to the benefits of hiding a pill in the peanut butter!

Similar situations

If you’ve watched the video clip in the link above you will know that Doug starts by using a question to establish a connection with his audience by asking about a similar situation: ‘Who here has ever had … (in this case a pet who got sick)?’ After telling the story he then makes the link to the business situation. There is no benefit to creating stories or similar situations if you don’t create a link to the core message of your presentation.

What are the similar situations your audience could find themselves in?

Getting soaked in the rain …

Learning to ride a bike …

Slipping on ice …

Sun bathing …

How can that help you to make your concept or idea tangible, rather than conceptual?

Don’t ‘we’ all over your presentation

I have discussed the benefits of using ‘we’ rather than ‘I’ to acknowledge the contributions of others (in Step 3), but there will be times in your presentation when it is better to use ‘I’ to emphasise ownership of the subject, statement or proposal. Showing personal commitment in this way can help generate confidence in the audience.

A picture speaks a thousand words

Sometimes when presenting a concept or an idea you need a visual to help the explanation.

I remember watching an architect speak at length about his amazing house designs and their energy-saving benefits. But it wasn’t until he actually showed pictures of some built examples of his work that his presentation came to life.

What visuals can you use to help people understand and grasp what you want to convey?

Skill 3

Presenting to motivate and inspire

If you are seeking to motivate and inspire your listeners, I’m guessing you may also be looking for them to take some action: perhaps respond quicker to customers, work well towards a tight deadline or boost morale so that fewer complaints happen. Whatever the final outcome you are seeking, presenting to motivate and inspire is a huge challenge if you are not motivated or inspired yourself.

Use of fear

You’ve probably all been motivated by fear at some point. Possibly by a manager (I can certainly recall one such person in my corporate life who used to bawl at someone at random, and we were never sure when it would be our turn). Possibly the fear related to the consequences of missing a deadline or losing an account. However, while the use of fear to motivate may work occasionally, it isn’t a lasting motivator, nor does it generate a flourishing environment in which to work.

Here is one example to illustrate ‘away from’ motivation:

The fire alarm goes off at work; you rise from your chair and make your way quickly to the nearest exit. Once safely outside you stop, start to mill around and chat with others. The motivation has gone and you wait until you can safely re-enter the building. You are not motivated to continue walking and go for a 10-mile trek. Why not? The fear stimulus has subsided and the reason for walking has gone.

Lasting motivation comes from the inside

It is not about finding an external key with which to unlock others, or kicking them into action, or even offering the proverbial carrot. Lasting motivation comes from the inside, from the values and beliefs of the individual, and is demonstrated though their actions. So how can you access it?

Motivating or inspiring from the inside

To really motivate or inspire someone you need to touch their inner emotions. In a presentation format, I suggest you use compelling stories, create emotional links and invite rather than tell your listeners to take action.

Storytelling

There is great power in using metaphors and stories to get your point across rather than directly telling (see Step 5). Human beings have a natural tendency to resist doing as they are told – just watch any four-year-old child. As adults we still have that four-year-old’s response within us, even though on a day-to-day basis we supress the socially unacceptable response of ‘no, I don’t want to’ that bubbles up inside us.

Using stories can give us a way to bubble up emotions in our listeners.

Creating emotional links

Aristotle knew the power of emotional connections and stories. While he could see that logical argument alone should persuade others, he was wise enough to understand that it didn’t.

In The Art of Rhetoric, Aristotle proposed three steps that need to be in place to construct persuasive argument: ethos, pathos and logos (these are also mentioned in Step 7).

- Ethos is your credibility in your audience’s eyes; why should people listen to you and why should they believe what you say? Often this is based on the reputation of the speaker, not the job title.

- Pathos is the emotional connection you make with your audience during your presentation.

- Logos is the logical argument, the facts and figures, the data and the reasons that back up your ideas.

The use of pathos in a presentation

Advertisers know these three steps well. They also know that the most persuasive, motivational or inspirational step is pathos. If you watch a TV advert you will often find it is selling an emotion rather than the product’s features. Advertising agencies often use this technique in car adverts, but it is also used for many other products. And it works.

So find ways you can incorporate a link to the emotions of your audience. You might start with where they are now, then tell them where you want them to be, describe the difference, return back to where they are now several times during your presentation, before ending on where you want them to be and why it will be great when they get there.

Invite versus tell

If you invite someone to come on a journey, they have the right to refuse. In the same way, in a presentation if you invite people to come along with you they have the right to refuse. Equally, they have the choice to accept your invitation – and most people will do so. However, if you tell people they are to go on a particular journey, you may find you hit more resistance. A tell method of communication tends to butt up against the ego of the listener.

This can be demonstrated through the martial art of Aikido, which I have begun to practise. If, as a ‘victim’, we resist an attacker’s approach and try to force them to the ground they, in turn, will resist and the strongest will win. However, a skilled Aikido practitioner will accept the energy of the attacker and use it to invite the attacker to come along towards the ground, and as if by magic they fall. (I am as yet far from skilled in Aikido!)

If you genuinely want to motivate and inspire others don’t tell them what to do, unless you really have to – such as to prevent a commercially wrong decision being taken, or when the fire alarm sounds. Use the language of invitation and you will encounter less resistance and increase motivation and inspiration, and boost agreement with your views.

Metaphors

Step 5 provided some examples of the use of metaphors. Listen out for metaphors in everyday situations … the English language is prone to using metaphors and similes to express meaning, for instance:

- She didn’t seemed bothered, it was like water off a duck’s back.

- He took to the new process like a duck to water.

- She had an idea she wouldn’t let go of, like a dog with a bone.

- You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink.

Is high energy essential?

It is often thought that the most motivational speakers are those with the highest energy. This might be a fair conclusion if you confined your search to America. There, speakers such as life coach and motivational speaker Anthony Robbins use big gestures, a loud voice, large emotional mood swings and bounce around on stage a little like Tigger in a sweet shop.

However, other speakers, such as the Dalai Lama, use their energy in a very different way. They are passionate about their topic, but present in a quiet, self-assured way.

To motivate and inspire others, you don’t need high energy but you do need to be passionate about your subject. You do need to make eye contact. You do need to gesture, but in a manner appropriate to the topic. And you do need to be congruent with your own natural style – and be authentic.

Skill 4

Presenting change

Why is it that when a presentation about a change in the processes, staff structure or procedures of an organisation is made it is often met with indifference at best, hostility or a passive–aggressive approach at worst?

How many times have you listened to someone presenting information on a forthcoming change and heard how great it will be without any recognition of the disruption the change will cause, the emotional feelings the audience might have towards the change or the reasons why it is being implemented?

Change presentations are often poorly received because they aim to put the change into a good light without any acknowledgement of the issues the change process will bring.

Not everyone likes change; only about 10% of people like things to be different year on year. Most people, 55%, prefer things to stay the same1 (from NLP world www.nlpworld.co.uk/nlp-glossary/m/metaprograms/).

When presenting change, however positive a move you think it is going to be, you must recognise that not everyone will see it that way. Yes, present the positives, but only after you have acknowledged the resistance, objections and emotions your audience may be feeling.

If you use the word ‘may’, you are not telling your audience to feel a certain way, you are acknowledging what might be. For example, ‘Some of you may be feeling a little frustrated or are thinking “here we go again” … while others may be wanting to stop having to ….’

Before making your presentation, brainstorm what is going to stay the same. That way you can present the change with sameness and difference in mind, rather than just difference. For instance, staff might:

- still be working at XYZ company;

- still be coming to the same office with the same colleagues;

- still have the same computer system.

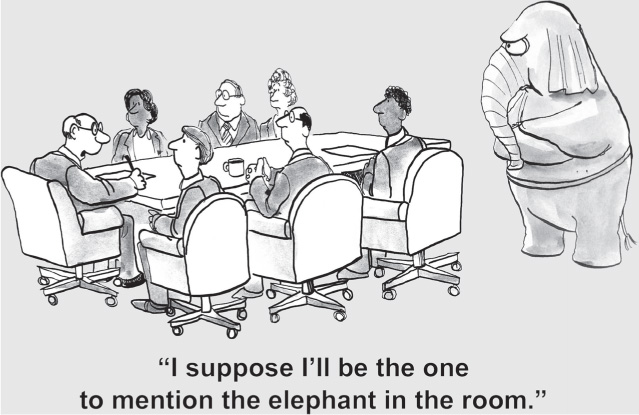

Don’t ignore the elephant

As discussed above, it can be very tempting to present change in a wholly positive light without acknowledging the negatives. It may be the upheaval, extra training or additional hours to be worked to get used to the change, or a reduction in hours and overtime as the new process will be faster than the old. Whatever it is, acknowledge it. If you ignore these issues during your presentation it will be like having an elephant enter into the corner of the room; everyone sees it and no one mentions it. The elephant will not go away, so greet it warmly, discuss it and then deal with it. Only then can the change be effective.

Use pathos

When presenting change, be sure to include pathos (see also Step 7). Too many change presentations focus on the logical argument, the reasons why the change is necessary, who will be involved and the timescale and process. While all that does of course need to be included, you won’t get the buy-in until you use pathos to engage your audience’s emotions, not just their logic.

It might be worth having a quick reread of Step 7 before planning your change presentation.

Where are you and where are they?

Finally, as the presenter of the change you will have had time to think about the process, the impact, the benefits and the drawbacks. Remember, when you present the change it is possible that your words could be the first people will have heard about it.

Taking the ‘change curve’, attributed to and adapted from psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and her work on bereavement, it is likely you will already have moved through denial and anger to commitment, whereas your audience may well be in denial. Denial, with the emotions of shock or anger, is usually the initial reaction to change. Very few people greet change with glee at first.

Upon understanding a little more about the change, and realising it is going to happen, people may move onto the resistance phase. Here it is common to think that it will happen to others but won’t apply to them, or that they absolutely will not use the new system or process.

Exploration starts when people ask questions such as ‘how will that apply to me?’, ‘what is the impact of it on the team?’ and ‘why is the company doing this?’.

Commitment is the ‘right, let’s get on and do this’ phase.

Often, as the presenter, you have had a chance to move through the first three of these four stages and are at least at the stage of exploration, if not commitment. There is, therefore, a mismatch between your emotional state and that of your audience, who may be back in denial or resistance. Be prepared to acknowledge this in your presentation and reflect on the stages you have gone through, articulating those to your listeners.

1NLP World, www.nlpworld.co.uk/nlp-glossary/m/metaprograms

Skill 5

Presenting a team brief

How you currently conduct your team briefs, or indeed whether you have one at all, will affect which of the tips below are appropriate for you. As you read through this skill, keep your team in mind, the characters in the team and its objectives from the business point of view. Then choose which tip(s) to try out and decide which one to start with. Making radical changes may work, or you might decide to make them incrementally.

The purpose?

What is the purpose of your team brief? Is it to ensure that everyone updates each other on their current projects, or so that everyone hears the same corporate message at the same time? Be clear on the purpose or you may find you have more than one meeting muddled into a format that is contained within an hour on Monday mornings. Would it be better to separate your meetings into two shorter ones?

Engaging the team

A team brief can often be seen by the team as simply an information-giving exercise. If this is the case, why are you meeting up? Usually more is wanted from the brief, but not always obtained, such as a gathering of viewpoints, discussions or decisions. To achieve these extras the team needs to be engaged.

Sharing the chairing of the team brief can help increase engagement, as can using some of the facilitation tips described in Part 3. But perhaps the biggest tip of all here is to ask the team what they want. Your team will have ideas of their own; they will know what is working and what isn’t. If you can draw those out and agree on what will be implemented, you will increase engagement far more than if you decide on your own, as the team leader, the format of future team briefs.

How long?

Some of the team briefs I attended in my time as a corporate employee lasted for up to 2 hours. Two hours every week is a lot of time out, and it wasn’t always productive. Occasionally we would have a really useful session discussing a new product and how it would benefit our customers. But most of the time we were bored.

Short and sweet

Attention spans are getting shorter according to scientists. Keep the briefs short, to the point and then the content will be more memorable.

Stand-up meetings

Hold stand-up meetings rather than sitting down in a meeting room. One of the most useful briefings I used to have with a boss was every morning, for around 10 minutes, as we opened the day’s post. That was before the advent of emails, and it gave us a chance to chat through the day, staffing and any other issues that were arising before I went to my team. We always stood up to talk.

Have an agenda

Even if it is a reoccurring weekly meeting, such as the team brief, there should be a purpose and an agenda, preferably circulated to everyone in advance of the meeting.

Start and end on time

Too many meetings don’t start on time, usually because someone isn’t present. Begin your briefing when you say you will and people will soon learn that they need to be there for the start. If you decide to wait until everyone is present, you will find the actual start time moves away from the scheduled start time and keeps moving … in the wrong direction.

Don’t read the brief

One company I have worked with sends out daily updates and weekly briefs to their staff by email. The team leaders and the team receive the updates and these form the basis of the team brief. Unfortunately, some team leaders resorted to the easy option – reading out the email. Imagine the engagement of their staff at those meetings. If this is your company format, find a way to raise discussions based on points in the email; don’t just read out the email as your team can do that on their own.

Identify the key areas

What is really essential for your team to know?

Can you describe the key points in 5 minutes or fewer?

Separate the ‘must know’ from the ‘nice to know’.

Extra information

Holding shorter, more focused briefings means you won’t be able to cover everything in detail at the time. So be sure to direct your team members to where they can find out that extra bit of information.

The middle manager’s dilemma

Being a middle manager and presenting a team brief can pose an extra dilemma: how to pitch the message. Are you at one with senior management or are you ‘one of the troops’. You will need to reflect both points of view, which can be a delicate balancing act. One thing that can help is to translate the language of a briefing out of management-speak or jargon and into the colloquial language of your team, so that they can relate to it more easily. As a middle manager with feet in both camps, you should be well placed to do this.

Own the message

This is especially important if a brief is likely to be controversial. Your team will see through the façade if you try to present a viewpoint you don’t agree with. To get around this dilemma, you need to demonstrate that you understand the reasons behind the message. Then it is possible to say that while you don’t fully agree, you do see why it is so, and you can ask your team to follow your lead in complying with the brief without undermining your own integrity.

Focus

Finally, when you are presenting a team brief, keep people on topic. Avoid a moan-fest. Allow and encourage constructive disagreement, but not moaning, destructive or vindictive language or viewpoints. See Challenge 6 for more details on how to handle people with a persistently negative viewpoint.

Skill 6

Presenting a new project

While I know a lot about making presentations, I know less about project management. So this section has been written with the generous help of Keith Abbott, an expert in project and programme management.

When preparing your presentation consider the feasibility of the project, as you will probably need to answer the following questions:

- Is the proposal consistent with the company strategy?

- Does a market exist?

- Is the proposition technically feasible?

- Is the proposition commercially viable?

- What is the plan and resource estimates to deliver?

- What are the risks?

Often projects will have:

- a sponsor;

- an owner;

- a project manager;

- a project team;

- project stakeholders.

Key stakeholders usually include the sponsor, the project manager, the organisation and the customer. There are also other categories of project stakeholders, such as internal, external, suppliers and contractors, government agencies or society at large. Managing stakeholder expectations is one of the major challenges of project management, because stakeholders often have very different objectives that may come into conflict with one another. In your presentation, rather than ignoring the potential conflicts, acknowledge them and, depending on the time available and purpose of your presentation, it may be useful to open this up to discussion and input from those present to help address and manage the conflicts.

When presenting a new project you will need to create and deliver a clear statement of the aims, enabling the following questions to be answered:

- Is this in line with business objectives?

- What have we got to achieve?

- How will we know when we have finished?

- How will we know that we have done well?

- When has the project got to complete the tasks?

- How much will the project cost?

You may also need to include the following:

- Project scope – the scope defines and clarifies the boundaries within which the objectives of the project will be met, to ensure it is working to achievable limits. It may also, by way of further clarification, help to identify those areas that are out of scope.

- Work breakdown structure – the WBS is the basis for the project plan and needs to be reviewed in some detail at the kick-off meeting.

Project organisation and resource requirements

The management structure and organisation of the project must be clearly defined. Resources required to run the project must also be identified and a commitment obtained that they will be provided.

Initial cost estimates

Identify the initial cost estimates before the kick-off meeting so they can be collated and discussed at the meeting. If cost estimates are not available before the kick-off meeting, they should be derived as far as possible during the meeting and actions assigned so that the full costs can be included in the project scope definition document. The level of confidence in the accuracy of the estimates needs to be stated.

Milestones and major deliverables

A list of major project deliverables and target milestone dates should be presented and reviewed at the kick-off meeting.

Management system

Identify and articulate the management system. This helps to ensure that things go to plan, stating how the project will be reviewed, how risks, issues and problems will be managed, and how changes will be controlled.

Assumptions, constraints and dependencies

Any assumption, constraint or dependency should be identified and its impact understood. External dependencies should be identified and actions put in place with the owning functions to underpin the dependency.

Risks

A list of risks to the success of the project need to be drawn up, along with a plan to mitigate the effect of the risks should they occur. Generally, each risk will be assigned an owner who must assess the risk and develop mitigation plans. This list forms the basis of the risk register.

Immediate issues and actions

A list of immediate issues will have emerged during the discussion. As the presenter, it is useful to summarise them at the end, identify what needs to be done to resolve them and list any other actions.

Focus on needs

Successful presentations start by focusing on the audience’s needs, and that also holds true for successful project presentations. Refer back to Step 2 for a reminder on how to do this.

Skill 7

Presenting at a meeting

When making a presentation at a meeting, how formal you choose to make it will depend upon the nature of the meeting. For instance, if there are just four people present, a stand-up presentation with a full slide show may be overkill.

First of all, I suggest you refer back to the questions raised earlier (in Step 1):

- Why do you want to make a presentation?

- Is a presentation the appropriate way to get your message across?

Once you have decided that it is, and not simply opted for a presentation as a default method, then consider your audience, the situation and the message to determine the most appropriate style.

To use or not to use slides?

I recall being in a meeting at the end of the working day; I was with a colleague and we were pitching for a piece of work. My colleague had prepared a PowerPoint presentation and had copies of the slides printed and bound into a pack for each of the four people in the meeting. We had a brief discussion in the car park and decided that, as we were the last to present that day, the prospective client would already have heard more than enough PowerPoint presentations, so we would ditch the PowerPoint and talk them through the proposal in a more informal way.

This allowed the meeting to open into a discussion between the two of us and the prospective client, where they could ask us questions as they cropped up rather than feeling a need to wait until we had finished our presentation. Equally, it gave us an opportunity to ask them more questions so we could tailor our bid accordingly (and we got the contract).

Sit down or stand up?

When making a presentation in a meeting, if you need to establish your credibility and assert your authority you may find that standing up helps. Your body language is likely to be more assertive, and by standing you are in charge.

If you choose to sit down make sure you don’t fall into the following traps:

- Don’t slouch.

- Don’t fiddle with your pen.

- Don’t doodle.

- Do make eye contact.

- Do sit upright.

- Do lean forward.

Getting your point across

However informal the presentation, if it is going to be remembered you need to do your preparation. There is nothing worse than a meeting running over time because people have waffled, gone off on tangents and been unclear in their message (though sadly these are often failings of many meetings in business).

Be clear about your key message

Know what you want your audience to do, say, think or feel as a result of your presentation.

Be sure to summarise your key point at the end.

Getting heard

Often, in meetings, the challenge is finding air time. How do you get heard when everyone else is talking? Even if you are allotted a slot on the agenda, depending on the culture of your meetings this doesn’t necessarily mean you will have silence while you speak. Maybe you don’t want silence, as some interjection definitely shows engagement and listening is taking place; but I would suggest you don’t want side conversations happening either.

If you observe a side conversation taking place, you could ignore it. However, a more effective option might be to stop talking, look at the people chatting and see if they look up. If after a few seconds, which may seem like minutes to you, they are still talking, as the presenter you have the right to interrupt them. Using their names to get their attention and asking if they have a point or a question that would be useful to share is one way of doing this.

Speak up

When giving a presentation in a meeting you will want to speak a little louder than you would if you were making a contribution to the meeting during a general discussion. Raising the volume slightly will help inject energy into your voice, ensure you breathe more deeply and provide an air of authority.

Where do you sit?

If you have a choice, take a seat where you can see the person chairing the meeting. You’ll be able to make eye contact with them and enlist their support in controlling the meeting while you are speaking. When giving your presentation you do not have to do this from the place you have been seated. If there is an obvious front-of-the-room spot, get up and move there for the duration of your presentation. Choosing to present from your seated position might undermine your message, whereas choosing to get up and move demonstrates you are in control, both of the meeting at that time and also of your message.

Skill 8

Presenting on a conference call or webinar

When you know you will be presenting remotely, such as on a conference call or webinar, planning ahead of time is essential. Keeping people engaged is a bigger challenge when presenting remotely, so unless you are on a video call, you may need to prepare more slides rather than fewer. That way you can use the changing screen to help with engagement … but be sure to remember to move your slides on as you progress through your presentation. It is very easy to forget to do so.

The planning process has many similarities with those for the presentations already discussed. Here is a summary of some questions to consider:

- Why this topic?

- Why you?

- What might be the listeners’ knowledge, skills and concerns?

- How can you make it interesting? Think of stories or examples of recent cases to include.

- What key messages do you want to get across? How can you highlight these?

- How long is it for? Can you chunk it into shorter webinars, or bring in guest speakers?

- Will you be asking virtual attendees to break out into groups for discussion?

Effective conference calls are well-chaired and allow everyone to speak without talking over each other. Having brief introductions at the start of the call so everyone can hear each other’s voices will help identify the speakers if they are not well known to each other in the first place. As the presenter you will need to agree with the chairperson in advance whether you will be chairing the discussions on your presentation or whether they will be, and how this should be done.

Are they concentrating or bored?

Establishing a method of interjecting enables everyone to be heard. This could be as simple as saying your name to indicate you have a point you wish to raise. The chairperson then invites people to comment in order, by using the names. The chairperson will also know who hasn’t raised a point and can then invite them to add their comments.

And regarding the technology, think about these questions beforehand:

- What equipment will you be using?

- Can you test it beforehand?

- Where is the mic located?

- Where is the camera located?

- If there is a technical issue how can you access assistance?

- Can you record a back-up presentation in advance?

Tips for presenting your next webinar

Don’t

- Fiddle – either with your hair, a pen or anything else.

- Email at the same time as presenting.

- Have your phone on.

- Wear chunky watches or bangles that may clank on the desk.

Do

- Look directly at the camera.

- Have a strong opening, introducing yourself by name, and include housekeeping rules such as how to ask questions and where to write comments.

- Use pictures, including a photograph of you on the first slide to personalise your presentation.

- Introduce each speaker if you have guest speakers.

- Pause after you have made your main points.

- Avoid jargon and abbreviations – if they are necessary, explain them the first time they are used.

- Vary the pitch and pace of your delivery. This helps to keep the attention of your listeners and variety keeps brains attentive.

- Slow down your rate of speech; most of us unconsciously speed up when we make any form of presentation. The rate to aim for is between 140 and 160 words per minute.

- Pronounce the beginnings and ends of your words. This helps everyone clearly understand what you are saying and avoids mumbling.

- Summarise key sections and summarise key points at the end.

- Provide an overview of what comes next; for example, whether the webinar will be available as a podcast and, if so, how it can be accessed.

When presenting to a camera you have a choice of going up close and filling the frame or being further away. If you go for the up-close option, have some lighting positioned at 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock as it will help prevent you looking washed out. This isn’t always possible, but do consider whether you are in the shadow or the glare.

If you decide to go for the further away option, be aware that your listeners may be looking at what else is in the room, who passes by the glass panel in the door or what is going on in the street – unless you can turn on a corporate backdrop as a screen.

If you decide to write out a script to read, ensure it is in colloquial language. We speak with far less grammar than we write. There are a number of autocue apps available, made especially for tablets, and these can make reading a script easier. Being too close to the camera when reading a script can show in your eye movement, so practise your reading distance. The further away you are, the less likely your eye movement will be noticed. If reading in a close-up position, try to keep your eyes on the same line (usually the top line) as the prompter scrolls.

Add in inflections, pauses and emphasis when reading. This should help to avoid your script appearing as if it is being read, and therefore potentially becoming boring to the listener.

Skill 9

Presenting data

When presenting data, the common trap is to put too much information on your slides, too much in your presentation and provide little explanation about what the data really tell the audience, why they need to know the information and what impact it could have.

I encourage you to join me on a mission to prevent poor data-rich presentations from happening.

Know your key message

If you can articulate why the data are important, what the information tells the audience and why they need to know it, you can start to plan a professional, clear, content-rich presentation. I say content-rich because that doesn’t mean it has to be data-rich. The data needs to back up your message, but the audience don’t have to have all the data given to them during the presentation.

If you refer back to the tips on presenting to sell a product (see Skill 1), I introduced the concept of FAB:

- Features;

- Advantages; and

- Benefits.

Perhaps, when looking at presentations containing data, it is appropriate to rename the concept DAB:

- Data:

- Advantages: and

- Benefits.

Ground your presentation in the data, but pick out some key points (advantages) that will be of particular interest to your audience and tell them the impact these will have, or the implications (benefits).

Craft your slides carefully

If you are using slides to present your data, do not, I repeat, do not put all your data onto the slides. I’m sure you can think of a presentation you’ve sat through where the presenter refers to the results of a survey, or a financial figure or a bit of technical information that is buried in the midst of the rest of the figures on the screen.

If there is an important piece of information for people to grasp, put it onto a separate slide, in big letters, yes I mean big …. Depending on the context, a size 64 font in Arial Black could work really well.

Watch out for nit-pickers

There is always someone who will spot the typo on your slide, a flaw in your data or challenge you on the statistical calculation you have used. Accept it; don’t argue on your feet unless you are sure you are right and can conclude the point quickly. If necessary, have a separate conversation with the questioner about their point after you have finished your presentation.

Someone making a detailed or trivial point of this nature may be expressing a need have their ego ‘stroked’. As a presenter it is your role to do the stroking, rather than lock into a battle of the egos. You may need to concede the pedant is right, or simply may be right. But telling them they are wrong and you are right will only inflame and prolong the situation.

Activities create understanding

During your presentation, can you ask your audience to take a moment to discuss the data with the person sitting next to them, in particular the key point of X and the implications they see … or something along those lines?

Having your audience do something active with the data, such as a task or discussion, enables them to understand the data more clearly, keeps the interest levels high and also provides an opportunity to generate questions.

Breakout groups can also be asked to manipulate or analyse the information and then come up with a recommendation for the way forward.

Less is more

You will already have seen this concept earlier (in Step 7) and it applies nowhere more so than when dealing with data. Make data interesting and less complex by distilling the key points. Use comparisons to generate interest, such as with competitors or past experiences.

Figures, tables and graphs

There are good and bad uses of figures, tables and graphs. I don’t purport to say not to use them, but do use them sparingly. Create ones that, if you are showing them on a screen, will be readable from the back of the room. When presenting figures it is often more helpful to use percentages or fractions that the brain can relate to more easily. Give the detailed information on a hand-out, not in your presentation.

For an example of good and bad graphs, see the online content for more suggestions and refer to Steps 4 and 6.

Consider audience expertise

Take account of the expertise of your audience. If you don’t know in advance what it will be, then assume a lower level of knowledge. You can always pitch your presentation higher, but if you have pitched it too high it is often difficult to think of on-the-spot examples to bring it to a lower technical level.

Are you presenting to accountants or engineers? What jargon will they be familiar with, what is industry-specific and what is product- or company-specific?

If in doubt, spell it out.

Skill 10

Presenting in 5 minutes

Making a 5-minute presentation should, on the face of it, be easy; after all, you don’t have long to speak. However, the shorter your presentation is, the harder it can be to prepare and deliver an effective message.

When you need to keep it short, keep it simple

There isn’t time for long explanations, long stories to illustrate your key points or lots of data on your slide presentation.

Take time to plan

Planning a 5-minute presentation can take longer than planning an hour-long presentation because you need to work out the essential messages and then show how you can present them in a straightforward yet engaging way.

Beginning, middle and end

In a short speech, even inside 2 minutes, there is still time to have a beginning, middle and an end. However, don’t spend too long at the beginning with setting up the premise of your talk otherwise you won’t have time left to cover the middle and the end effectively.

When giving short competition speeches of 2 minutes in length, I had to practise wrapping up my conclusion within 30 seconds. I still have a tendency to take a little longer than 30 seconds but the principle is there; a summary of what has been said and the key points can be made in a short amount of time … but you need to cut out the waffle. At the end you don’t retell the message, you just cite the key points.

For example, when providing the weekly review of the team’s progress, you could list all of the achievements and challenges you have encountered that week and the areas in which you are still seeking solutions.

If you have just 5 minutes I suggest you do the following:

- Outline what you will cover: ‘This week I’ll focus on one key achievement, two challenges and end with a request for help in the area of XYZ.’

- Then provide the overview: ‘Our key achievement was in providing client A with their equipment on time and within budget. We have found challenges in the production line for product C and also in our night shift staff, as the team leader has been off sick. We overcame these by …

Our remaining issue is that of the supply chain. To this end I am asking for your suggestions on how we might create closer links with them (and then open it up for a brief discussion).’

- To close: ‘If anyone has further suggestions on the supply chain, please email or speak to me afterwards.’ You could end there or add, if it hasn’t been included earlier: ‘In particular I’d like to thank Joseph and Jules for their perseverance in handling the challenges and congratulate the production team for achieving client A’s timescale.’

The aim of a 5-minute presentation is to provide a quick overview, not an in-depth analysis. By all means state that you have conducted an in-depth analysis and give an overview of the results. Then point your audience to where they can find out more information, or provide it on a hand-out.

A word about PechaKucha

A different short-presentation format was devised in 2003 by the artists and architects Astrid Klein and Mark Dytham. Initially a way for young designers to meet, network and show their work in public, it has now become a recognised presentation format.

The name PechaKucha comes from the Japanese term for the sound of ‘chit-chat’, and the format is to deliver a presentation consisting of 20 images that change every 20 seconds. The whole presentation therefore lasts for 6 minutes and 40 seconds.

The rapid change of slides and short timeframe keeps people focused on the topic. There are now PechaKucha meet-ups all over the world, so if you would like to practise this format look one up: www.pechakucha.org.