11. The Best Ways to Grow Your List

Sending emails without permission or buying lists is not for everyone. In fact, if executed poorly, they are likely not the best strategies for most email marketers. However, these methods can and do work. We want to nudge you—the email marketer—to push the envelope a bit. We’re asking you to do some testing, to see what works best for you and your audience. We’re not advocating that your entire email marketing strategy be built around popups, one type of opt-in, or the sending of emails without permission—far from it. Instead, be a bit rebellious.

Know that we’re not advocating doing anything wrong, illegal, or unethical. None of these tactics are such. But the email marketing purists have determined them to be less than ethical or optimal in the past without taking into account that not every rule works for every audience. We simply want to show you that some of these so-called “no-no’s” according to the industry experts and purists are not only not off-limits but can sometimes prove to be rather effective.

Ready? Let’s go.

Spiders, Scorpions, Snakes...and Popups

If you’ve spent more than five minutes of your life online, you’ve likely encountered some form of a popup—an ad that appears without warning or a new tab or window that shows up suddenly without any explicit action on your part. In fact, in the early days of the Internet, popups seemed to be everywhere. As soon as you clicked a link, your screen would fill with popups. Every time you closed one, seven more would appear. Often, the only way to actually stop these crazy popups from taking over all the real estate on your screen was to restart your computer. (Hello, Ctrl+Alt+Del!)

In 2012, traditional popups are not nearly as prevalent as they were a decade ago. Anti-popup software, now built into many Internet browsers, including Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, and Google Chrome, have made popups a lot less common. However, marketers have discovered workarounds to popup blockers, new ways to execute interruption marketing. With these workarounds comes somewhat of a resurgence of popups as an effective tactic to grow email marketing lists.

Mark Brownlow, journalist, blogger, and independent publisher of Email Marketing Reports, says popups are like “spiders, scorpions, and snakes”: “Email marketers have been reluctant to use ‘in your face’ website sign-up forms that in any way resemble...popups of the past,” he said.1 Instead of using popups, many best practice folks suggest growing your list by including a form that’s embedded directly in a webpage. We don’t disagree.

However, not all email address collection forms are created equal. The four most common ones include the following:

• In-line: Chapter 2, “How to Grow Your List,” covers this form. In-line forms live directly on a web page. They are quite effective in growing your email list.

• Popup: This form opens in a new tab or window in an Internet browser. Unless a user manually accepts them, popups are typically blocked by default.

• Pop-over: This form hovers within a webpage. They cannot be blocked by most Internet browsers.

• Lightbox: This form is similar to the pop-over. It appears on top of the content on the webpage. However, when it shows, the background content becomes semi-transparent, making it easier to see the lightbox.2

In-line forms remain the most popular form, but the lightbox form is gaining ground as a way to grow your email marketing list. Email service provider AWeber is one company that allows its clients to create and embed lightbox opt-in forms on various web pages. Additionally, third-party providers such as Popup Domination (popupdomination.com) provide lightbox services.

You’ll often see the terms popup and lightbox used interchangeably. To be clear, a lightbox is a form of popup. However, not all popups are lightboxes. Think of the terms’ relationship as similar to the rectangle/square or bourbon/scotch/whisky relationships. Unless otherwise stated, we’ll also be using the two words to mean the same thing.

One of the nice parts about most popups and lightboxes is that they can be customized to appear after a specified period of time, on a specific webpage, when a link is clicked, after someone visits a certain number of pages on a site, or upon leaving a certain page. This customization ability allows the marketer to test various approaches to discover which is the most effective way to grow their email lists.

However, regardless of their flexibility, popups are not for every marketer. You might be reading this now and thinking, “I hate popups. I’ll never (ever) use them.” We don’t blame you. We don’t care for them too much either. But what if we told you they worked? What if, after including a popup or lightbox, your list doubled or tripled in size? Would that change your opinion? What if we told you that not only would you experience a huge jump in your list size, but also you would have zero complaints? Would you test them?

In the last few years, many email marketers—both in the business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) space—have found incredible success by including a popup or lightbox as a means to collect email addresses.

Installing a Lightbox to Increase Opt-Ins

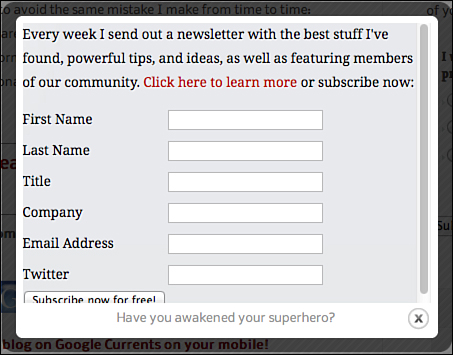

Jeff Ginsberg is the founder and CEO of The eMail Guide—The Search Engine for eMail Marketing (theemailguide.com). Since the site launched in 2009, Ginsberg has included an email opt-in form on the right sidebar of many pages on the site (see Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1. Ginsberg includes an email opt-in form on the right sidebar of many of The eMail Guide’s web pages.

This opt-in form was responsible for growing The eMail Guide’s email list to more than 1,200 subscribers. His monthly list growth ranged from a low of 30 to a high of 100. Although this growth was not terrible, Ginsberg was confident he could grow his list at a higher rate by making a few changes.

In August of 2011, after hearing lots of chatter and positive comments about popups, Ginsberg decided he would test one out. He chose a third-party service called Popup Domination and customized his lightbox (see Figure 11.2) to appear on all pages ten seconds after someone landed on the site. Additionally, he changed the settings such that the lightbox popup would display once every seven days. In other words, if someone had not been to a page on The eMail Guide for seven or more days, the lightbox would appear.3

Figure 11.2. In August 2011, Ginsberg launched this lightbox popup on The eMail Guide. It appears after being on the site for ten seconds.

Ginsberg saw an immediate bump in email subscribers. In the first month, his number nearly quadrupled—from 100 to 388. More than 170 of those opt-ins could be sourced back to the lightbox. The number of additional email addresses collected from the lightbox in September was 219. In the next four months, Ginsberg added almost 700 new subscribers: from the lightbox alone!

Ginsberg also added a source field to his web opt-in forms so that he could track where each new email address was coming from. This number might surprise you: 83 percent of all email addresses collected on theemailguide.com came from the lightbox!

Any guesses about how many complaints Ginsberg has received in six months? If you guessed “zero,” you would be correct.

Using Lightboxes on Blogs

Even after reading how successful Ginsberg has been with his list growth, you might still be saying, “I don’t care. I hate popups. I would never install one on my website or blog.” You are certainly not alone. In fact, Chris Penn (whom we introduced in Chapter 3, “Let’s Get Technical”) doesn’t like them either, yet he still has one on his blog (see Figure 11.3).

Figure 11.3. Chris Penn introduced this popup on his blog in November 2010 and, thanks to its enormous success, has had it there ever since.

You know by now that Penn likes to test various email marketing tactics to see what works best for his audience. He sends ugly emails, puts a big (ugly) unsubscribe button at the top of his emails, and includes some humor in his alt text that can be seen with images off. Armed with that information, it should come as no surprise that Penn has also tested popups on his blog to collect more email addresses.

“I personally don’t like them much on other sites I visit,” said Penn, “but I had to remind myself of the cardinal rule of marketing: I am not my customer.”4

Sounds a lot like what we’ve been saying in this part of the book: Best practices are those that work best for your audience.

Penn is a self-proclaimed data nut. If he is going to test something, he’ll almost always use data to not only set up the test, but also to report back on the results. Before installing the popup, he was averaging around 30 new signups per month to his personal email newsletter. From the first day he launched the popup, his subscriber numbers began to increase. At the end of the first month his average shot up from 30 to 133. As of February 2011, it was trending at 250 per month: a 733 percent increase.

“The numbers are incredibly compelling, despite my slight personal dislike for the marketing method; for this blog, the method works incredibly well,”5 he said. It’s hard to argue with a 733 percent increase. Not only that, but Penn’s lead conversion ratio—the number of new email subscribers as a percentage of absolute, unique visitors to his website—increased from a pre-popup number of a half percent to more than two percent after the popup was installed.

In case you were wondering, Penn uses a WordPress plugin (a third-party application specifically designed for the blogging platform) called WP Super Popup Pro. It allows for a lot of customization, including the ability to specify how long before the popup appears, showing it once then not again for a certain period of time, and so on.

But will popups work for larger companies and brands? What about those in the business-to-consumer (B2C) space? Can using popups work for them as well? The short answer is yes—but you already knew that as you’re well on your way to becoming an email marketing rebel.

Adding Lightboxes on a B2C Site

Chapter 2 introduced Patrick Starzan, Funny or Die’s VP of Marketing & Distribution. Starzan shared with us that the company’s number one goal of marketing was to drive traffic back to the site. Funny or Die has many methods to reach this goal, email marketing being one of them.

However, it has not been a quick process. From a list point of view, Starzan said things started off quite slowly. The company began adding various opt-in forms on the website, on the homepage as well as other in-site landing pages. It also focused on growing its social media presence at the same time.

It also wanted to stay true to its brand. “[Growing our list] was a slow process. We had never done something this organic, but knew we had to use comedy,” said Starzan.

Starzan said the company began seeing popups and lightboxes on many websites, but it didn’t love what it saw. Many of the popups were “right in your face.” So the company decided to build a lightbox of its own a few years ago, one that fit its needs and was consistent with its brand (see Figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4. The Funny or Die lightbox is simple and incorporates humor to capture email addresses.

Before launching the new lightbox, Starzan and his team decided that if they noticed a drop in page views or a huge backlash from their community, they would eliminate the lightbox immediately. They also implemented a critical, customized lightbox setting from day one. For visitors to see the popup, they had to first view three pages on the Funny or Die website.

“We didn’t want to ask for something before we gave them something,” said Starzan. “If you’ve gone three pages in, you’ve gone far enough to [hopefully] like it so we could then ask for something—get your email address.”

This approach is one we don’t see all that often but fully support. In some ways, slapping a popup on a visitor’s monitor immediately is like asking someone for her phone number before you learn her name. Take a few minutes to be sure visitors are interested, then ask for their email address.

Funny or Die also thought long and hard about ways to “not make the popup annoying.” It didn’t want its popup to be something visitors would rush to close or see and immediately close the page, leaving the site, never to return. To accomplish this goal, it first made sure the lightbox was very large—“two to three times what we’d seen in the marketplace,” according to Starzan. In fact, its lightbox fills up nearly half of the entire page.

Next, it chose to make the lightbox very clean with only a touch of copy and one field (for email address). The messaging is simple and clear. The only content before the email address field is:

“JOIN THE funny OR DIE NEWSLETTER. The best of Funny or Die. PLUS EXCLUSIVE CONTENT.”

That’s it! No hard sell. No social proof highlighting the number of other email subscribers. No detailed explanation of what subscribers would get by opting in.

Finally, Starzan said that keeping the tone consistent with the Funny or Die brand was critical. “We wanted to be very transparent, to be sure people knew that we really just wanted their email to deliver Funny or Die content on a consistent basis.”

Notice the text below the email address field. It reads, “We will not use your email for anything sneaky.” If someone chooses to not opt in, he has two options—click the “X” in the upper right of the lightbox, or click the NO THANKS, I CAN’T READ button. This button allows people to tell Funny or Die they don’t want to opt in, but in a humorous manner.

“Using humor on the popup lets people’s guards down in a subtle, nice way,” said Starzan.

The lightbox has been an integral part of Funny or Die’s email list growth strategy. The company is adding thousands of new email addresses every day and has grown the list to more than one million names in just four years. Nearly 80 percent of all email subscribers can be attributed to its lightbox popup.

On top of that, it has not experienced any negative backlash. “We didn’t see any adverse affects of having the popup. To this day, I have not heard anything [negative] about it and we’ve been doing it for nearly four years,” Starzan told us. Additionally, the company’s unsubscribe rates are quite low: only 0.2 percent.

Starzan said it’s all about meeting the expectations of people. “Once we have their email addresses, we want to make sure why they signed up is what we are delivering, the benefit. Great content and frequency is important to us. [The low unsubscribe rates] tells me two things: growing the list in the right way and delivering the right content is critical.”

Park City Mountain Resort Tests a Popup on Its Winter 2010 Website

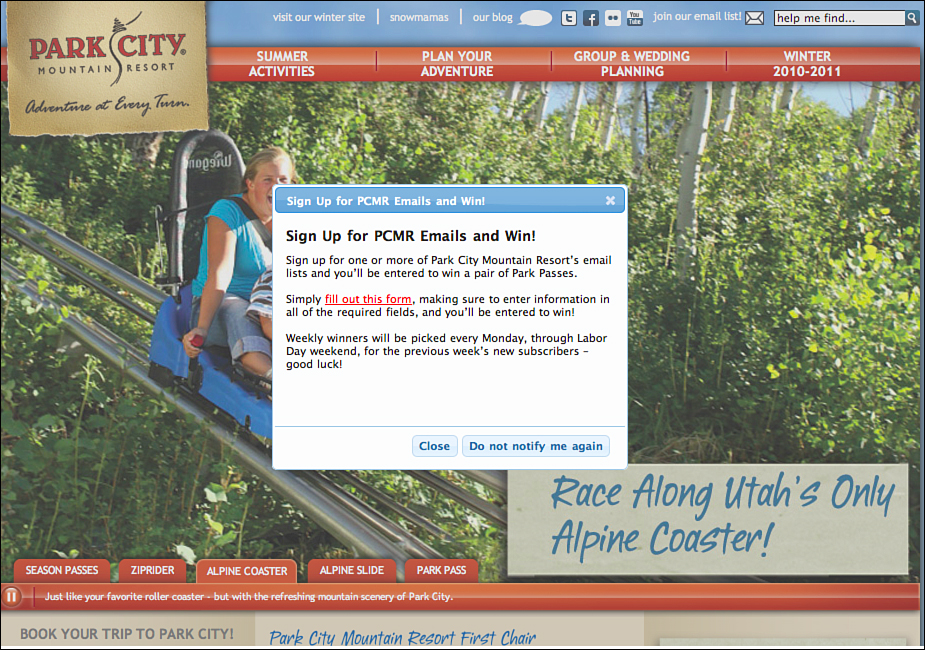

Another B2C company who has effectively used a popup to grow its list is Park City Mountain Resort (PCMR). Open year-round in Utah, the resort caters to mountain bikers and hikers in the summer, and ski and snowboarders in the winter. Because of this seasonality, PCMR completely overhauls its website twice per year: once for the summer season and again for the winter.

In the later summer/early fall of 2010, as it was gearing up for the switch to its winter website, it decided to test a popup form to collect new email subscribers (see Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5. PCMR’s email list immediately grew after it added this popup to its summer 2010 website.

It added a lightbox popup, set via a cookie, to show for first-time visitors. After a user took action—either declining or closing the popup or signing up via the form—PCMR would not display it again.

We love this popup for many reasons. For one thing, the messaging was clear and concise: three paragraphs, each one sentence long. The first told readers what to do (sign up) and introduced the incentive (“you’ll be entered to win a pair of Park Passes”). The second included a link to the subscription form (“fill out this form”) and reinforced what was required to be entered to win. The third set proper expectations about the prize (“winners picked every Monday...”).

Also, the form included three options: a link to fill out the form, a button to close the form, and a button to close the form and not be notified again. People tend to like it when they have a choice.

But more important than how it looked or what the messaging said, the real question is this: Was the popup successful in helping PCMR reach its goal of growing its email list? You bet! PCMR had a 2,200 percent increase in email opt-in signups from July 2010 to August 2010.

“The lightbox popup worked because we did provide an incentive to sign up in terms of winning the drawing and it wasn’t just the ‘value’ of receiving the emails, plus the popup was cookied [sic] to not show once a user opted in or out,” said Eric Hoffman, Interactive Marketing Manager at PCMR.

There is no question popups and lightboxes are controversial. Many people, both consumers and marketers, avoid them at all costs. However, if implemented properly, they can have a huge positive impact on email list growth. We talked about the importance of asking for someone’s email address in Chapter 2. Popups take asking to a whole new level with their “interruption” nature. Yet if the popup is relevant, timely, and valuable, it can work.

The possibility does exist that popups and lightboxes do cause some potential email subscribers to recoil in disgust, close the window, and abandon the website never to return. In fact, some backlash likely exists; however, the marketers showcased in this chapter have found that the visible pros (huge list growth) outweigh the negatives (potential lost subscribers). So, what they feared might have happened actually turned out to be a nonissue.

A trickier issue exists in knowing whether a single- or double-opt will fly with your audience.

Choosing an Opt-In: Single or Double

In regard to growing your email list, the tactics are endless. As discussed in Part I, making the opt-in obvious and the form easy to fill out are important, as are being creative and using humor, using technology such as QR codes, smartphones, and social media, and even taking the offline channel into account. Or be a bit rebellious as discussed in this chapter and test out a popup or lightbox to add more email addresses to your list.

However, no matter which methods you choose to grow your list, all email marketers must decide whether to allow subscribers to be added to their list through a single or double opt-in process:

• Single Opt-In: A subscriber provides his email address to a company, usually via a web form. As soon as he clicks Submit or Enter, the user is added to the email database. In some instances, a company sends out a thank-you email indicating that he’s successfully been added to the list. In other instances, the thank you comes in the form of a welcome email. Either way, no other action is required by the subscriber.

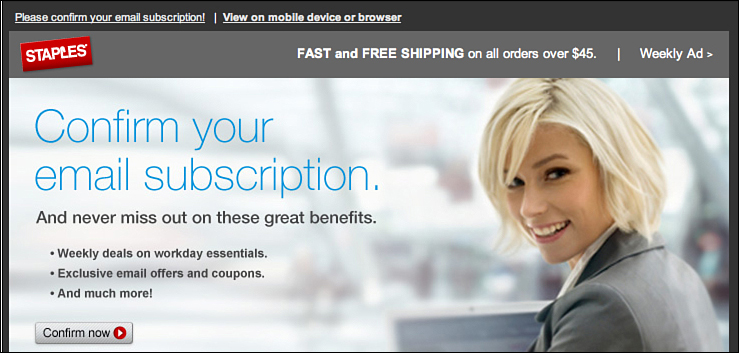

• Double Opt-In: A subscriber provides her email address to a company, usually via a web form. However, before she is added to the email database, she must reply to the email or click on a link to confirm her request to opt in. If she doesn’t reply or click the link, she is not added to the list. See Figure 11.6 for an example of a confirmation email.

Figure 11.6. In this confirmation email from Staples, if a user does not click on the button in the image or the link in the preheader, he will not be added to the email list.

So, much like the question proposed in Chapter 3—to check or not to check—we now ask a similar question: Should you use single opt-in or double opt-in?

Several years ago the case used to be that double opt-in was the gold standard in the email marketing industry. Recently, a switch to single opt-in seems to be occurring. As always, the answer to which opt-in to use depends on who you ask.

Several email service providers strongly suggest or even force a double opt-in method for all of its customers. MailChimp requires its customers to use a double opt-in process when using its signup forms. No way exists to turn off the confirmation email. (However, its customers can create their own single opt-in forms, but MailChimp does not recommend that approach.)6

Similarly, AWeber enables double opt-in by default for all subscription methods. It says double opt-in is “the best way to ensure that you have both permission and the audit trail necessary for good message deliverability.”7 It can be turned off, but doing so takes some work. Other providers, although not explicitly stating it, prefer their customers grow their email lists through double opt-in.

But not everyone agrees that double opt-in is the way to go. In fact, Bill McCloskey, founder of Only Influencers (and technical advisor to this book—thanks, Bill!), is not even sure how double opt-ins landed on everyone’s list of best practices. McCloskey thinks double opt-in is a terrible idea—assuming you want to grow your list, that is.8

We agree with McCloskey and believe this gold standard is outdated and no longer necessary—in most cases. Even though we’ll present both sides of the single/double opt-in story, let’s be clear where we stand: Single opt-in is the best approach.

Making the Case for Double Opt-In

If you want to ensure a cleaner list—one that has fewer bad email addresses—double opt-in is likely the best route to go. Sending a follow-up (confirmation) email ensures a real human is behind the opt-in. For the email address to be added to the sender’s database, a button or link must be clicked to confirm the subscriber truly wants to receive emails.

Confirmation emails also prevent accidental opt-ins or intentionally being subscribed by another person. The messaging in many confirmation emails allows people to easily opt out if they “subscribed in error.” Many of these double opt-in emails note that if they ignore the email, they will not be added to the sender’s list.

Finally, by sending a confirmation email and requiring someone to click a link or button before she is truly opted in, the sender can validate the email address. Because many Internet Service Providers (ISPs) look at the percentage of invalid email addresses when calculating domain reputation, the more senders can do to minimize this number, the better. Forcing a human to click the confirmation link pretty much ensures the email address is real.

Many people also argue that a double-opted-in list results in more engaged subscribers. In 2011, email service provider MailChimp took a random sample of 30,000 of its users with email list sizes between 500 and 1.5 million who had sent at least ten campaigns. Some sent every day, whereas others sent a few times a month.

For this sample, it found those who used a double opt-in approach had a 72.2 percent increase in unique opens and a 114 percent increase in clicks. Arguing with those numbers is hard. However, remember that the data is only representative of MailChimp’s clients and does not necessarily represent a true split test. Although MailChimp’s clients can create their own single opt-in forms, MailChimp strongly discourages it and requires “full double opt-in” when using its forms. Still, the MailChimp numbers do not lie and should be taken into consideration if your audience profile is similar to its clients.

“Garbage in, garbage out” is one of the main arguments against a single opt-in strategy. Those opposed to single opt-in worry about bogus email addresses—bots (or your friends, co-workers, family, and so on) automatically signing you up to receive certain emails. We’ll address how to control the bot problem shortly, but as far as people signing up other people to receive emails, does that really happen anymore? We don’t think so.

Making the Case for Single Opt-In

When DJ was a sales associate at Bronto in 2009, he had a reputation as a talker (not much has changed). This sometimes proved to be a detriment. DJ had a tendency to keep chatting after the sale was closed, giving the new client an opportunity to change her mind. DJ’s boss, Matt Williamson, often coached him to “Stop when they say ‘yes.’”

How does this relate to a double opt-in method? Asking potential subscribers—people who have just asked to be added to your email list—to open their email and then click a link to confirm their subscription, is similar to talking after the sale is over. They’ve already said “yes.” They’ve raised their virtual hands (or clicked the “Sign me up!” button) and asked to be added to your list and start receiving emails from you. However, you’ve now said, “Are you sure? Are you really, really sure?” You’ve required them to take an extra step in the process. Stop when they say “yes!”

Consider this fact: Only 76.5 percent of all commercial email reaches the inbox.9 Those email marketers who send double-opt in messages run the risk of a portion of those emails never being delivered. On average, nearly one quarter of folks who want to receive email from an organization might never have that chance because the message does not reach their inbox. Before you say, “But wait! Using that same logic, one quarter of welcome emails will never reach the inbox!” remember that with a single opt-in approach, you already have permission to email those subscribers. If the welcome email doesn’t reach them for some reason, they are still opted in and will still (likely) receive other emails from you. The possibility exists that the first email was temporarily blocked or just went unnoticed by the new subscribers.

However, if potential subscribers do not receive the confirmation email—an email that’s usually sent just once—they will never be added to your list. All of that time, effort, and money that went into earning those new subscribers will be lost. They’ll never get any email from you, ever.

Let’s not forget the cost of sending an additional (confirmation) email. If you are using an email provider that charges by total emails sent, as the majority do, this extra email will cost money. If you follow the advice given in Chapter 3 about sending a welcome email, you now have not one but two additional emails for every new subscriber added to your database. Depending on the number of new monthly subscribers, this (unnecessary) expense could add up quickly.

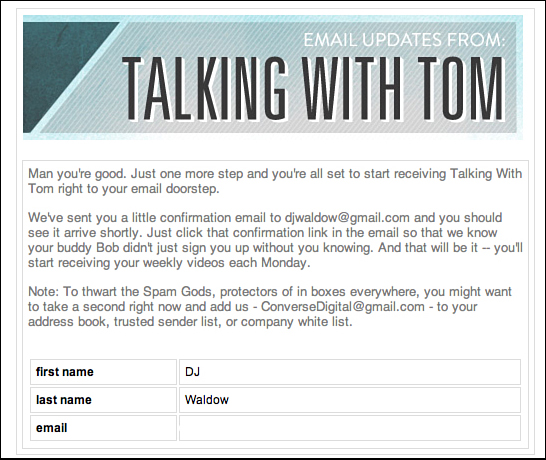

Finally, even email that lands in inboxes is not guaranteed to be opened, let alone read. With the average open rates for all email marketing messages hovering somewhere near 20 percent, a confirmation email getting lost within an already cluttered inbox is quite possible. To be fair, by setting proper expectations, like Tom Martin does (with humor) in Figure 11.7, your confirmation email is more likely to get opened and clicked. However, this often is not the case.

Figure 11.7. Tom Martin uses humor to remind subscribers to check their inbox for his confirmation email.

In a 2009 white paper, email service provider iContact said that “around 40 percent of subscribers that initially opt in fail to ever confirm their subscription. This means, that out of every 100 new subscribers, you would never be able to reach 40 of them. Losing 40 percent of your newsletter subscriptions over the long run could have a large negative impact on your sales.”10

Even if you think the iContact number of 40 percent might be on the high side, arguing with the 76.5 percent inbox delivery rate from Return Path (as mentioned in the Introduction) is hard. Would you be willing to lose 23.5 percent of potential subscribers?

Using a single opt-in approach ensures an easy process for your subscribers as well as a larger email list for you. Win-win, right? You are not asking your potential subscribers if they are really sure. You are not asking them to jump through hoops or take extra steps to confirm they really want to receive email from you (after they just opted in). They put their email address in a form on your website, and bam! They’re on your list. Assuming the email address was properly typed, nearly every single person who asks to be added to your email list will be. You win. They win. Everyone is happy.

Sure, a chance exists that some email addresses will be typed incorrectly, either accidentally or intentionally; however, plenty of companies provide services to ensure an email address is valid before adding it to your database. Some tactics, such as requiring a potential subscriber to enter his email address twice, often cuts down on human errors. Other services, such as including a CAPTCHA (where a subscriber must perform a simple task such as typing the letters seen below the form), prevent non-humans (bots) for signing up to email lists with a malicious intent. Additionally, many email service providers will do a check for validity on all new email addresses before they enter their system.

But remember! The rules only apply to you and your audience. Where there’re success stories for double opt-in practices, there are also success stories for single opt-in practices.

Village Voice Media Moves from Double to Single Opt-In: Sees Significant List Growth

Village Voice Media (VVM) is a media company based in Phoenix, Arizona. It owns more than 14 publications across the United States and uses email marketing as a means to keep in touch with its subscribers. Prior to 2010, it required all new subscribers to confirm their email address (double opt-in) before being added to the company’s email lists. The main reason it went this route was to help mitigate some of its deliverability issues from the past. As mentioned earlier, a double optin process can lead to a cleaner list.

But when Ron Hauwert was hired in early 2010 as the “Email Czar” for VVM, he immediately shook things up. He submitted a proposal to the management team with the goal of growing its email program. According to Hauwert, 50 percent of VVM’s potential new subscribers were lost in this process. In other words, they never clicked on the confirmation email. Fifty percent!

On Hauwert’s recommendations, VVM moved from an in-house, homegrown email platform with double opt-in to an email service provider (ExactTarget) with a single opt-in. The results were quite dramatic.

VVM made a few other tweaks to the signup process, including only requiring an email address; however, just factoring in the move from double to single opt-in, its monthly list growth doubled.

Among the reasons you would use a double opt-in over a single one include making doubly certain the people you will send your emails to have absolutely taken not just one, but two steps to confirm they want your communications. This falls in line with the spirit of the CAN-SPAM Act and is a pure opt-in approach to email marketing.

However, while not as prevalent as it used to be, there still is a chance that someone can intentionally sign someone else up for an email list. For companies who sell adult-related services or products such as cigarettes, liquor, gambling, or other forms of adult entertainment, this can be an issue. For this reason, we believe these types of sites are an exception to the “always use single opt-in approach” and instead are better suited for double opt-in. For legal reasons, it’s always better to be (double) covered. Additionally, religious organizations are probably better off employing a double opt-in strategy. The general rule of thumb is that if your organization sells or promotes products and services that can be controversial, double opt-in is a safer bet.

However, going overboard on the opting in is another best practice, or rule, we’re here to help you rebel against. Now let’s look at why you would actually send emails to people who haven’t opted in first.

Sending Emails Without Permission

In 1999, the best-selling book, Permission Marketing, written by marketing guru Seth Godin, preached a new way of doing marketing. Instead of interrupting potential customers, permission marketing focuses on creating trust and building brand awareness to develop long-term relationships with prospects. This, according to Godin, is accomplished only by communicating with people who have expressed an interest in your company, product, or service.

Even though Godin discussed email marketing in his book, he was really talking about marketing as a whole. However, the conversation was not lost on email marketers. You won’t find a more hotly debated topic in the email marketing industry than permission.

In regard to permission in the email world, most people fall on either extreme of the continuum. On one side are the companies, vendors, and email marketing consultants who believe wholeheartedly that no one should ever send an email without explicit, opt-in permission. One the other side are those who believe it can work—for some marketers, in some industries—if executed properly.

In the United States, sending unsolicited, non-permission-based email is not illegal. However, in the European Union, Australia, and Canada, it is. For the purposes of this section, we’re going to focus on U.S. law.

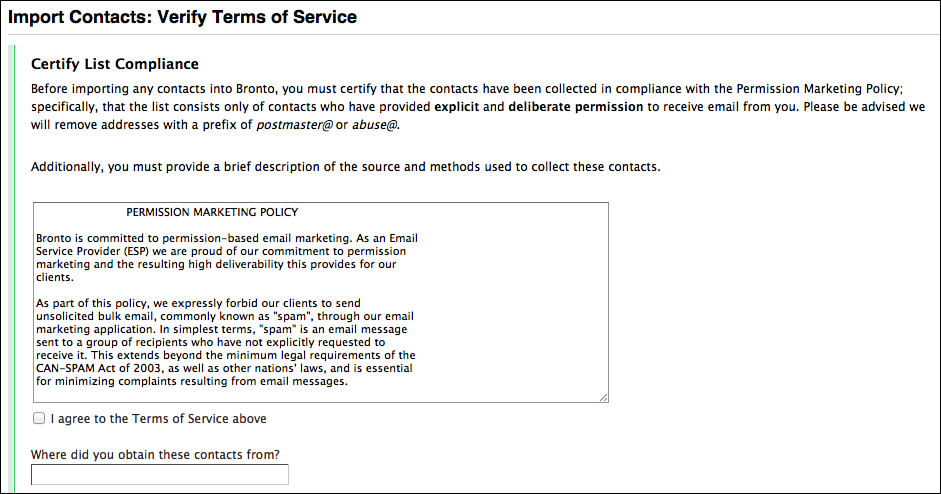

Several U.S.-based email service providers (ESPs) have chosen to make their permission marketing policies a lot stricter than the baseline requirements outlined in the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 (and its 2008 updates). For example, in Bronto’s Permission Marketing Promise, it “expressly forbids any of our clients to send unsolicited bulk email, commonly known as ‘spam’, through our email marketing product.” Its definition of spam is “email sent to a group of recipients who have not explicitly requested to receive it.”11

ESP CampaignMonitor states that “spam is any email you send to someone who hasn’t given you their direct permission to contact them on the topic of the email.”12 Again, notice the use of the phrase direct permission. However, it seems to soften a bit in regard to explicit versus implicit permission. Its policy states that its customers can email subscribers through its system if someone has made a purchase from that sender within the past two years. Although the company still advocates for including an opt-in checkbox as part of the purchase process, this form of implied permission is still permissible under its policy.

Bronto also incorporates its permission standards for every new customer email list imported into its application, reminding users of its policy (as shown in Figure 11.8). Notice how they’ve bolded the phrase “explicit and deliberate permission.” Its permission marketing policy is reiterated below that text and users have to manually check a box stating they agree to the Terms of Service. Finally, Bronto requires a brief description of the “source and methods used to collect” these email addresses. In regards to permission, Bronto is quite clear on its policies.

Figure 11.8. Before importing email addresses into Bronto’s application, customers are required to agree to its permission marketing policy.

Yet, what exactly qualifies as an explicit permission email opt-in depends a lot on who you ask. We define it as a person who knowingly and willingly asks to be added to your email list.

Based on this definition, a non-explicit permission email would fall into the following categories (note that this list is not exhaustive):

• Adding someone to your list through a pre-checked opt-in box on a web form

• Adding someone to your list after he’s made a purchase (but not opted in)

• Adding someone to a different list within your database

• Using an email change of address (ECOA) service that updates inactive or “bad” email addresses to ones that are valid

• Using an email append service that matches an email address against other data, most often first and last name and mailing address

MailChimp breaks down various scenarios of how it defines an email list it allows customers to send through its application. As it says, “MailChimp is a tool for sending email newsletters and permission marketing.”13 Some of the “it’s not okay to send to this list” scenarios include the following:

• Purchased lists

• Lists obtained from a tradeshow host

• Email addresses collected from business cards

One could debate the various levels of permission here, but suffice it to say that none are explicit. None of the preceding involve someone knowingly and willingly asking to be added to your email list.

However, in the United States, explicit permission is not required by law. Ken Magill, author of MagillReport.com, confirms this:

“No, explicit permission is not necessary. Marketers who don’t get explicit permission are playing a dangerous game, but, no, it’s simply not required. A marketer who doesn’t get explicit permission but sends relevant, segmented, compelling email to customers based on past interactions and exercises good list hygiene ...probably won’t have any trouble.”14

Magill says that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) ultimately decide which emails get delivered regardless of permission policies. If you think about it, do ISPs really know whether a subscriber gave explicit permission to opt in to your list? Nope. How could they?

In a 2012 survey, ESP BlueHornet asked a series of questions to a mix of 1,033 consumers about their views of email marketing.15 This group all lived in the United States and was between 18 and 40 years of age. Also, 79 percent were employed and 77 percent had an income more than $35,000.

One of the questions asked was, “Is it OK for companies to send promotional emails if you made a purchase, but didn’t sign up to receive emails?”

An overwhelming 75.8 percent of respondents said no, it was not okay.

We are dedicating a section of this chapter to asking you rethink this “rule” of email marketing. We are in no way telling you to run your entire email marketing strategy by a non-permission model. Far from it. However, we are suggesting to test non-permission email marketing tactics along the way. They are not illegal (in the United States) and many companies have been successful sending non-explicit permission emails.

Sending an “Opt-Out” Email

In the summer of 2010, media company KSL.com changed ESPs. At the same time this Salt Lake City, Utah, company made this switch, it decided to add an additional email campaign to the mix: a “group deals” email similar to Groupon and Living Social. KSL.com sent an email to its entire subscriber list of more than one million people informing them of this change. The copy of the email was quite short and included the following:

Also as of July 2010, all KSL.com accounts will be subscribed to our new group deals email. We are excited to offer all of our users these exclusive great deals. If you do not wish to receive our new deals just click this link to Unsubscribe. If you would like to receive them you do not need to do anything, but will have the opportunity to unsubscribe at anytime.

Did KSL have permission to send this email to its subscribers? Yes, definitely. The email was sent to everyone who had opted in to receive email from KSL.com. In fact, Daniel Coburn, Director of Operations and Support for Deseret Digital (who runs KSL.com’s email marketing program and oversaw this campaign) confirmed that everyone on the list had previously signed up for an account at KSL.com and had checked the “allow us to send you emails” option. In other words, they had opted in.

“Instead of assuming everyone on a sizeable list would want to receive the emails we decided it was best to say, ‘Hey you are already on our list, and we are going to start using it, are you sure this is what you signed up for?’” said Coburn.16

When these subscribers originally opted in to the KSL.com email list, they gave their consent, but this is where it gets tricky. They did not give explicit permission for KSL.com to send group deal emails. However, during the initial opt-in process, asking permission to opt in for group deal emails would have been impossible because KSL.com didn’t have a group deal email program. It had not even been conceived at that point.

When the idea for group deal emails was born, the KSL.com team had two options. It could have sent an email to its entire list, similar to the one mentioned earlier, instead including a big button or link to opt in. The downside to this option would have meant risking a substantially smaller group deals email list.

KSL.com chose the alternative. It sent an “opt-out” email. If subscribers did nothing, then they were going to start receiving the group deal emails. KSL.com did make it clear in this email that subscribers could unsubscribe from this new list immediately or anytime going forward.

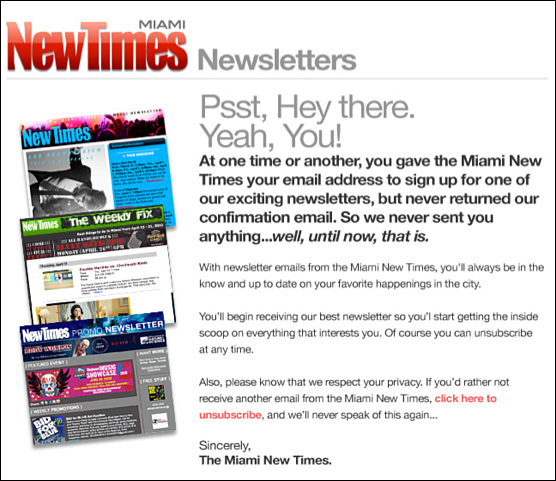

Hauwert, the “Email Czar” for VVM, also sent an opt-out email. While he was going through the transition from double to single opt-in, he noticed almost 100,000 email addresses from the past twelve months from people who had opted in but never clicked the confirmation email. He decided to send a “reclamation” email (as seen in Figure 11.9) to those people who had never finished the subscription process.

Figure 11.9. VVM sent a series of “reclamation” emails to people who had opted in yet never clicked the confirmation link.

The messaging included: “If you’d rather not receive another email from the Miami New Times [one of VVM’s publications], please click here to unsubscribe, and we’ll never speak of this again...”

The results:

• 36 percent bounced

• 1 percent unsubscribed

• 0.2 percent marked the message as spam

• 63 percent did not opt out

Although the high percentage of bounced email addresses could have been problematic, they were delivered using different IP addresses and sending domains so as not to negatively impact overall deliverability and sender reputation. The most recent email addresses were attempted first; the oldest were sent last. All said and done, the low unsubscribe rate and the 63 percent that was “reclaimed” (did not opt out) was well worth it for VVM.

However, another way to “reclaim” customers as email subscribers is by using something called an eAppend.

Using an eAppend

Another way to grow your list is to match email addresses from a third party with contact information in your customer database such as name, phone number, address, and so on. This process, known in the industry as an email append, or eAppend, can be an effective way to build your list. Using it is often frowned upon by many best practice practitioners because it tends to be on the outer edges of permission.

In the past, many eAppend providers sent opt-out emails. In other words, people receiving the eAppend email had to click a button or link indicating they did not want to receive email. However, several eAppend providers are now moving to an opt-in model.

Here is how a typical opt-in eAppend works:

1. You send the eAppend company your customer data file.

2. It matches the customer data against its database and sends an email to that list asking for permission on your behalf.

3. You are sent a file of email addresses who have opted in and agreed to receive email from you.

4. You send the eAppend company some money.

Does this method work? It can, if executed correctly and with some patience.

Bill Kaplan, CEO of FreshAddress (a Boston company that provides eAppend services), suggests that eAppends often provide better open rates and revenue compared to an existing house list. “The logic behind it is that at times, house lists can be tired,” he said. “They are used to hearing from you weekly or monthly, and might not be excited. But when you reconnect with a former customer and start to tell your story again, all of a sudden it’s fresh. They are excited to hear your story.”17

So what happens when a company uses eAppend and sends an email to someone who recognizes right away she never opted in to the company’s email communications? It happened to Karen Talavera. She is the Founder and President at Synchronicity Marketing, an agency that provides digital and email marketing strategy, training, coaching, and consulting. Talavera has been in the email marketing industry for more than a decade, on the email service provider side and now running her own firm. Suffice it to say she knows a thing or two about the email space.

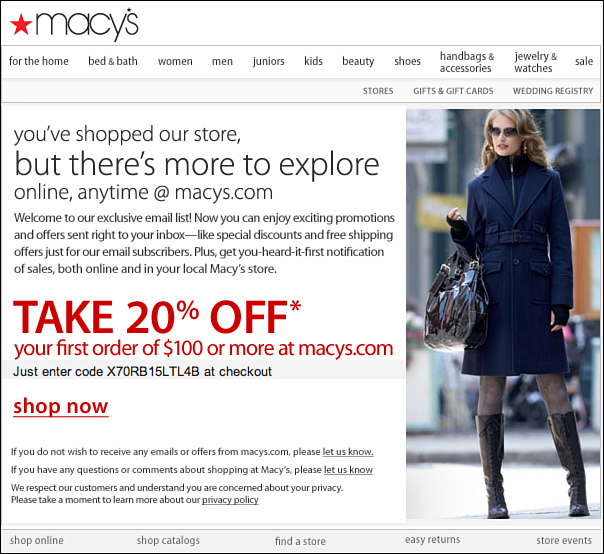

A few years back Talavera received an email from Macy’s (see Figure 11.10). We think it’s a pretty nice-looking email with a clear call to action. Then again, beauty is in the eye of the subscriber. Whether or not you like the email, it does have one issue with it. Talavera never subscribed to the Macy’s email list. Not via a webform on its website, not over the phone, not through a postcard permission request, not in the store with a sales associate, not through a smartphone app or a QR code (which didn’t even exist then!). Instead, at one point in the past, she had purchased some items from a Macy’s brick-and-mortar store.

Figure 11.10. Karen Talavera received this email from Macy’s—a company she never explicitly gave permission to email her.

As it turns out, Talavera was sent this email through an eAppend. Macy’s opted her into its email list because she had “shopped our store.” According to Talavera, Macy’s did not get her permission before sending this email. Notice the company still does provide a way for her to opt out; however, it’s not nearly as clear and obvious as KSL.com did in its email.

So what did Talavera do? Remember, she is not your average email consumer. She opened the email and liked what she saw. Talavera told us she was impressed with what she called a “compelling, contextually relevant” offer (20 percent off her first order of $100 or more at macys.com). Notice this offer was only valid on the Macy’s website, not in a physical store.

Talavera told us the offer was “on target” because it recognized her as someone who had purchased in one of Macy’s stores. She felt it was not only relevant to the communication channel (email driving online versus offline shopping) but was also exclusive to the channel. In other words, this was not an offer Macy’s would have included offline as well. It was meant to drive offline shoppers to buy online at macys.com. Finally, it had a deadline date.

At the end of the day, Talavera was not offended by this eAppend. She cannot recall whether or not this email led her to purchase something from Macy’s; however, she certainly did not opt out or report the email as spam.

Although using an eAppend is certainly skirting the comfort level of many email marketers who advocate for a total opt-in approach, it’s far from the most controversial of all email marketing practices that we argue are not always wrong to consider. That status is reserved for buying email lists.

Buying an Email List

When is it okay to buy an email list? Never! End of story. End of section. End of chapter.

In fact, that’s exactly what DJ said in a 2010 blog post.18 It was the shortest blog post he had ever written. The title of the post read, “When Is It Okay to Buy an Email List?” The body of the post said, “Never.” And that’s exactly what DJ thought at the time.

The post generated quite a bit of buzz: 207 shares, 43 comments, 112 Facebook shares, and several tweets. What was interesting is that of those who left a comment, many actually were in favor of buying email lists. This gave us reason to pause, to reconsider our “all or nothing” approach to list buying.

Before we continue with this section, let’s make something very, very, very clear. Neither DJ nor Jason personally advocate for buying lists of email addresses as a long-term strategy to grow your database. Although it might be effective in the short run, if executed improperly (which many list buys often are), buying email lists can have some serious, long-term, negative impacts.

But throughout the comments from various marketers in various organizations, there was a general theme—a common thread if you will. It was, “It depends.” Like most things in life, business, and the world of email marketing, every story has two sides.

To be clear, buying and renting a list is not the same thing. Buying an email list requires an exchange of email addresses—the list seller gives the list buyer email addresses in exchange for money. With list rentals, email addresses do not change hands. For example, if Company A wants to rent Company B’s email list, Company A would pay Company B for the right to have its message sent to Company B’s list. Company A never sees the email addresses on Company B’s list.

However, while several email services providers do not allow their clients to rent or buy email lists and send through their application, neither renting nor buying an email list is illegal in the United States. Nothing in the CAN-SPAM Act mentions either tactic.

“[It] drives me utterly bonkers when people start spouting off about how buying lists is illegal. It’s not,”19 tweeted Laura Atkins, founding partner of the anti-spam consultancy and software firm Word to the Wise. “If you are otherwise violating CAN-SPAM it’s an increased penalty, but harvesting/buying/making up addresses is not illegal.”20

So if it’s not against the law (in the United States) why do many people have such a strong, negative association with buying email lists?

Take the website caniuseapurchasedemaillist.com, for example. When you navigate to that URL, you land on a page that says, “No,” with the “I’m watching you” scene from Meet the Parents.

It’s pretty clear where the folks from MailChimp stand.21

Jim Ducharme, formerly of The eMail Guide, even went as far as creating a make-believe group: the Email Marketers Association for Puppy Protection (EMAPP). He invited all ESPs and responsible email marketers to join and help educate the public that buying email lists is wrong. He suggested that “every time you buy an email list a puppy dies.”22

We’re certainly not for the mistreatment of animals, but remember that these puritanical attitudes are centered around the notion that email marketing is best when it is done in a completely opt-in fashion. If an audience does not ask to hear from you, your emails may not be wanted. But as we’ve shown throughout this book, not every rule is true all the time. With the right list (audience), the right message, and the right timing on your send, you can be more successful with open rates and conversions than with a completely opt-in audience.

Know, however, that most every email service provider includes some mention of purchasing email lists being against their policy, but it’s not illegal. The far majority of email marketing practitioners are adamantly opposed to buying lists, but it’s not illegal. The authors of this book (us!) do not outright advocate for list buying, but it’s not illegal.

So why bother talking about it? As stated earlier, we don’t believe in absolutes—black and white. Always do this. Never do that. If a list broker approaches you with a “permission” list of hundreds of thousands or millions of email addresses for very cheap, run. If you use a reputable list service, yet the campaign is poorly executed, you’ll likely see a spike in complaints and the number of bad (undeliverable) email addresses will be high, both of which negatively impact your sender reputation and deliverability.

However, times occur when email list buying can and does work, most often in the business to business (B2B) space with small list sizes (no more than a few thousand), buying a very targeted list, and buying one that’s sent over a long period of time.

Craig Rosenberg is the Vice President of Sales and Marketing at Focus, a Software as a Service–based content marketing platform and network of more than one million contributors that makes it possible for brands to easily create, publish, and distribute content at scale.

He believes that list buying can work, yet tends to perform best for B2B marketers. Companies who buy a list, send one email, and “hope it works out” are often not those that are most successful.

“Relevancy rules,” says Rosenberg. “To be successful in B2B, you have to reach out to people who have not heard of you. Those people are less likely to call your email spam if it’s relevant.”

Rosenberg also stresses it’s a long-term process that requires multiple touch points—phone, email, direct mail, and so on—and patience. Remember that B2C and B2B are very different in regards to buying lists. “If you ‘cold email’ someone to buy immediately, that typically does not work,” said Rosenberg. “Instead, the cold email is to get them to raise their hand and ask for more information. Relevant educational material converts, not a one-time offer for 20 percent off.”

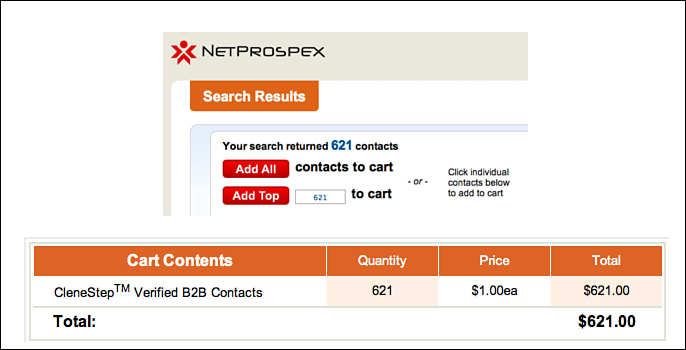

Several companies are in the list brokerage business. One of them, NetProspex, has a database of B2B contacts of more than 25 million. It uses a proprietary verification technology that ensures the email address is deliverable and the email sent complies with CAN-SPAM regulations. Purchasing a list of relevant, targeted business contacts, including their email addresses, is simple using NetProspex (see Figure 11.11).

Figure 11.11. Purchasing a list of targeted business contacts using NetPropex is easy.

However, it’s not the buying of an email list that’s difficult. Far from it. It’s as simple as selecting your criteria, searching, adding the search results to your cart, and purchasing. If you are willing to spend the money, buying a list is not too hard. Instead, what you do with that (hopefully) very targeted list can make all the difference in the world.

At this point you might be saying, “Great. So I understand that buying lists can work (in theory), but does it? Show me some case studies of it being successful!” That’s a fair request.

As we ventured out to find an individual or company that had purchased email lists, something very interesting happened: Everyone went silent. Nobody wanted to talk about it. It’s odd. We know it happens (as evidenced by companies such as NetProspex being in business), yet getting anyone to share their stories with us was a challenge. It could be because marketers have tried it and had a bad outcome. It could also be because the email marketing purists have preached “permission permission permission” for years and therefore many are skeptical to this list growth tactic. However, we believe that list buying does work, for some companies. The problem is that the email marketing purists out there have made list buying a dirty phrase, and nobody wants to admit they do it.

We were able to find one company (who requested anonymity, of course) to share some compelling data with us. Not only did list buying help it grow its list, but the list also positively impacted the top line!

Company A,23 a small chain of restaurants with three locations, purchased a bridal list for catering offers. The total list size was only 422 contacts and was sent over an extended six-month period of time.

The price of the list was $1,000 and it generated $16,470 in revenue. Not too shabby of a return on its investment, huh?

But before you run off and buy a list, let’s break down what Company A did with this list buy to help generate such an ROI. Notice the size of the list: 422 targeted email addresses. They didn’t purchase a list of hundreds or thousands.

Also, Company A did not send a one-time email and hope for stellar results. As Rosenberg mentioned, using a purchased email list is a long-term process. This list was sent a series of emails over a six-month period.

But can this sort of list buying work on a much larger scale? How about a list purchase of 48 million from a well-known multi-billion dollar company?

You read that correctly: A company purchased a list of 48 million email addresses!

In September 2011, as part of the Borders bankruptcy settlement, Barnes & Noble purchased all of Borders intellectual property for $13.9 million. A significant portion of this purchase price included Borders 48-million-customer database.24

As you can imagine, the email marketing “best practice” folks out there were up in arms. Emails, blog posts, and articles were being penned at a frantic pace, most of them criticizing Barnes & Noble for not only buying the Borders email list, but also the manner in which they communicated it to the 48 million (former) Borders customers.

Here is how it all went down: Quite logically, Barnes & Noble chose email as the medium to tell Borders customers about its recent customer database acquisition. That email, sent on October 1, 2011, to past Borders customers, announced this news and then some.

The sender (From name) was “Barnes & Noble” yet interestingly, the From address was [email protected]. In other words, although the email was “from” Barnes & Noble, it was really being sent through Borders. The Subject line of this email read, “Important Information Regarding Your Borders Account.”

The email, written by the Barnes & Noble CEO, William Lynch, informed Borders customers about “changes to their account.” Specifically, the email mentioned that Barnes & Noble had acquired some of the Borders assets including its entire customer list. The email alerted former Borders customers that they had until October 15, 2011 to opt out of having customer data moved to Barnes & Noble. The company provided in the email a unique link to visit in order to process the opt-out.

The actual language in that section of the email read:

“It’s important for you to understand however you have the absolute right to opt-out of having your customer data transferred to Barnes & Noble. If you would like to opt-out, we will ensure all your data we receive from Borders is disposed of in a secure and confidential manner. Please visit www.bn.com/borders before October 15, 2011 to do so. ”

Arthur Sweetser, former CMO and COO for email service provider e-Dialog and current CMO of 89 Degrees, thought the Barnes & Nobles list acquisition was brilliant. He offered this suggestion about purchasing lists of competitors that had gone out of business. “If you can convert 20 percent over to your brand and the price is right, I’d say you should consider yourself a BRILLIANT marketer!”25

We asked Barnes & Noble to comment on the Borders list purchase, the decision to send this opt-out email, and the results of the campaign. However, it declined to comment. We told you nobody wants to discuss list buying! (For the record, this wasn’t your typical list purchase, but rather an asset purchase. No one else could buy Border’s list. But it does offer some similarities that help us illustrate our points.)

Although knowing the exact outcome of this email is difficult, whether it lead to a high number of complaints (potentially causing deliverability issues for Barnes & Noble) or whether it was much ado about nothing for the Borders customers who received it, this much we do know: Barnes & Noble is still sending email to its customers on a regular basis. DJ averages about five emails a week from Barnes & Noble.

Coming Full Circle

There are recurring themes in this book we know you’re seeing. One is that the rules espoused by the industry experts over the years, like never using pop-ups or buying lists, aren’t exactly rules but suggestions based on either experience or, more likely, opinion. Another is that you have to determine which rules you are going to follow by taking these suggestions and testing them with your audience, in your industry, and around your product. Test with the attitude you want to prove the suggestion right, then test to try and prove the suggestion wrong. That’s the only way you’ll ever know what truly works with your customers.

In a sense, we’ve come full circle with this chapter. Part I of The Rebel’s Guide to Email Marketing focuses on how to build your list. Part II helps you understand the anatomy of an email. Part III dives into all these so-called rules and how you can be a better email marketer if you sometimes break them. Now this chapter circles back to growing your list and talks about how some of the rules involved in list building are also worth testing, perhaps even breaking, to drive more subscribers, reach, and even revenue.

However, you have another part of the book to go, and it’s an important one, too. Email marketing doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and the online world in the last 10 years has been overtaken with an exciting new method of interacting with your customers. Nothing has shaken up business communication quite like social media. And while many digital marketers think oil and water when they look at email, traditionally a one-way mechanism of communications for companies, and social media, more of a conversation-based or two-way method of communicating. We don’t. In fact, we think they go together and compliment each other rather nicely. So let’s dive in to Part IV and see how these two channels work together like Batman and Robin.

Endnotes

1. Email Marketing Reports, “Double your sign-up rate? Practical advice for popover forms,” December 20, 2011. http://www.email-marketing-reports.com/iland/2011/12/popovers.html

2. AWeber FAQs, Adapted from “How Do I Create or Edit A Pop Up Web Form?” http://www.aweber.com/faq/questions/225/How+Do+I+Create+or+Edit+A+Pop+Up+Web+Form%3F

3. Ginsberg, Jeff, “Using a Lightbox to Grow Your Opt-In EmailMarketing List,” February 12, 2012. http://www.theemailguide.com/our-world/feature/using-a-lightbox-to-grow-your-opt-in-email-marketing-list-by-jeff-ginsberg-dad_ftw/

4. Penn, Christopher S., “Do welcome popups work?” February 3, 2011. http://www.christopherspenn.com/2011/02/do-welcome-popups-work/

5. Penn, Christopher S., “Do welcome popups work?” February 3, 2011. http://www.christopherspenn.com/2011/02/do-welcome-popups-work/

6. MailChimp Support, “Can I shut off the e-mail that asks people for confirmation that they want to join my list?” http://kb.mailchimp.com/article/can-i-shut-off-the-e-mail-that-asks-people-for-confirmation-that-they-want-/

7. AWeber FAQ, “Can I Disable Confirmed Opt-In?” http://www.aweber.com/faq/questions/66/Can+I+Disable+Confirmed+Opt-In%3F

8. McCloskey, Bill, “Are You Really, Really Sure?” February 12, 2009. http://www.clickz.com/clickz/column/1700534/are-you-really-really-sure

9. Return Path, “The Global Email Deliverability Benchmark Report, 2H 2011.” http://www.returnpath.net/downloads/reports/returnpath_globaldeliverability2h11.pdf

10. iContact, “The Pros & Cons of Double Opt-In 2009.” http://www.icontact.com/static/pdf/Email_Marketing_Best_Practices_iContact.pdf

11. Bronto’s Permission Marketing Promise, http://bronto.com/permission-marketing-promise

12. CampaignMonitor, “What you need to know about permission.” http://www.campaignmonitor.com/resources/entry/558/about-permission/

13. “Is my list okay to use in MailChimp?” Updated 01/27/2012. http://kb.mailchimp.com/article/is-my-list-okay-to-use-in-mailchimp

14. Magill, Ken, “Permission Debate is Settled; Please Stop Yapping About it.” http://www.magillreport.com/permission-debate-is-settled/

15. Bluehornet Report, “Consumer Views of Email Marketing” http://www.bluehornet.com/assets/Report_Consumer-Views-of-EmailMarketing.pdf

16. Waldow, DJ, “Assumptions And Opt-Out: A Deadly Combination.” July 13, 2010. http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/131860 (see comment from Daniel Coburn).

17. Bannan, Karen J., “Establishing an effective email append strategy.” October 20, 2011. http://www.btobonline.com/article/20111020/EMAIL06/310209999/establishing-an-effective-email-append-strategy

18. Waldow, DJ, “When Is It Okay To Buy An Email List?” July 6, 2010. http://blog.blueskyfactory.com/best-practice/when-is-it-okay-to-buy-an-email-list/

19. Tweet from Laura Atkins (@wise_laura) on February 8, 2012. https://twitter.com/#!/wise_laura/status/167377428375810048

20. Tweet from Laura Atkins (@wise_laura) on February 8, 2012. https://twitter.com/#!/wise_laura/status/167376110907170816

21. MailChimp owns the domain, caniuseapurchasedemaillist.com.

22. Ducharme, Jim, “Every time you buy an email list a puppy dies.” July 6, 2010. http://www.theemailguide.com/email-marketing/every-time-you-buy-an-email-list-a-puppy-dies/

23. The client asked to remain anonymous.

24. Brown, Nick, “Borders, B&N get court’s OK on $14 million IP sale.” September 26, 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/09/26/us-borders-idUSTRE78P5US20110926

25. Fresh Address, “Partner Insights: Barnes & Noble’s Acquisition of Borders’s Email List.” http://biz.freshaddress.com/November2011_PartnerInsights.aspx