Habit 2

Break the management rules

How to become an electric manager

You’ll learn:

- Why traditional, ‘one-best-way’ management kills creativity

- How to avoid the hidden obstacles to creative management

- How to break the management rules – to become an electric manager

- How to design and manage your own creative process

- How to demystify where ideas come from – and use psychology to your advantage

“If new ideas are the lifeblood of any thriving organisation – and, trust me, they are – managers must learn to revere, not merely tolerate, the people who come up with those ideas.”

Mark McCormack, founder of the Global Sports Management Agency, IMG1

When Stuart Murphy was drafted into the satellite pay TV business Sky in 2010, as director of entertainment channels, his mission was to develop and commission hit shows. One of his first challenges was to explain to the rest of the business – people who looked after the technology platform, managed engineers or oversaw call centre operatives – how the creative process is managed.

‘There is something a bit Wizard of Oz about creativity,’ he said.‘ There’s a perception it just happens mysteriously in the bath – the famous Eureka moment. Then that lucky person goes off the next day to make £5 trillion. In my experience, the creative process doesn’t work like that. What happens is this: there are a few different conversations swilling around the business on different subjects: you might be thinking about what the customer wants; a big trend in society or an interesting new technology. Then somebody says something and – bam! – a bunch of previously disparate ideas coalesce around a single idea. Then a champion semi-bulldozes through the idea bringing fans along the way.’

To help people understand this unpredictable, conversation-based process, Stuart now presents an update at Sky’s six-monthly senior management get-togethers. ‘Instead of saying, at the end of the process, “Ta-da! Here’s the final show!”, we share the thinking process along the way. We’re honest about how we come up with new ideas. We pull the curtain back on The Wizard of Oz.’2

![]()

An important part of the role of manager in a creative business is to demystify and explain the creative process.

Why ‘one-best-way’ management kills creativity

Management feels like it has been around forever. But it hasn’t at all. It was invented by a man three years before the start of the First World War. A fastidious American engineer from Philadelphia, called Frederick Winslow Taylor, set out with his trusty slide rule to inject a little science into the tricky art of people management. In 1911, Taylor wrote his philosophy down in a grand treatise called The Principles of Scientific Management. It addressed a pressing challenge of the industrial era: how to mass produce everything from cookers to clothing. His solution was to develop ‘one-best-way’ for every task – from loading pig iron to packing boxes. His objective was to assign each worker a carefully designed task that could be repeated endlessly and faultlessly. Taylor’s thinking leads to the design of a job down to the last placement of a spanner on a bench: the Holy Grail of consistent results, very fast, very cheap. It’s a dream in which every worker bee performs to the limits of human productivity for every hour of his or her working life.

This rigid job conformity worked spectacularly well for quite a while. It was the foundation stone upon which the assembly line was built. Asking human beings to stay in one place to carry out a repetitive task whilst widgets streamed past didn’t work just for Henry Ford and his iconic Model T Ford; Taylor’s one-best-way did the trick for mass production of all kinds.3 In fact, without scientific management, our great-grandparents wouldn’t have benefited from cheap meat, refrigerators and carpets, amongst many other things. One-best-way lowered the cost of production and brought a whole new lifestyle within the grasp of the middle classes.

But there’s a problem. Like all innovations, management should evolve to stay relevant. But it hasn’t. Or, at least, not enough. One-best-way is not fit for purpose in a business environment where needs people to be creative. Of course, we need efficiency and productivity in business. But, encouraging people to be creative, inventive and innovative is at the other end of the spectrum to one-best-way. Businesses and teams that rely on creativity need lots of different ways; otherwise you don’t produce lots of different outcomes.

To manage creativity you need to be aware of Taylor’s ghost, which stills haunts modern boardrooms and offices. The problem is the intent behind it. Taylor may have spent a lifetime studying human productivity, but he didn’t have a lot of time for your average working Joe. He once described the sort of man suited to loading pig iron as: ‘so stupid and phlegmatic that he nearly resembles in his makeup the ox’. Taylor wanted management to be a ‘true science, resting upon clearly defined laws, rules, and principles’.4 Scientific management thinks of people as resources. Humans, in other words, are like oil, coal or paper clips: a resource to be used up.

Now, there’s been a debate raging between the ‘numbers people’ and the ‘people people’ for hundreds of years about what really matters in business. Of course, there is a place for rote systems and processes in some roles and teams: sales, production and customer service, for example. But, let me be clear: the people who work in creative businesses and job roles are not impressed one little bit by time and motion studies that reduce their contribution to something that can be codified, prescribed, scripted to the last dotted ‘i’ and crossed ‘t’. Their educational background and expectations of work and life markedly differ from an early 20th-century labourer sweating over pig iron. Frederick Winslow Taylor would be spinning in his grave.

![]()

Be honest. How much of your management style is based on the idea that the people reporting to you should follow your one-best-way? Before dictating, pause and ask their opinion to see if there’s a better way.

But…creative businesses do need management

At the end of the last century, Robert Sutton, a professor of management science and engineering at Stanford University, in California, set out to study the management of creativity in business. After a decade of analysis he wrote in a rather exasperated way: ‘After studying creative companies and teams for more than a decade, I’ve found them to be remarkably inefficient and often terribly annoying places to work, where “managing by getting out of the way” is often the best approach of all.’5

Sutton essentially was arguing that you can’t manage creativity; you can only manage for creativity. At a business level this is true. Creativity bubbles up from the right culture. But employees need to know where they stand. ‘Getting out of the way’ is not always possible, or practical. People need to know what projects they are assigned to, how long they’ve got, and what the objectives are. You do need some predictability and consistency: time sheets completed, services delivered to deadline, the same accounting practices, and consistent employee behaviours linked to the company’s overall values. Complete hands-off management does not work, and is not reflected in the ‘creative industries’ themselves. Any business, however creative, has budgets, deadlines, objectives and pressing customer needs. All businesses, even creative ones, need management.

So, while I’m happy to help throw scientific management out of the office window, it needs to be replaced with something. Electric management is a fresh approach: it breaks the rules by its intent to empower people. It is the only way to run a business that offers products or services that require creativity, knowledge and expertise. Before I offer you my manifesto for electric management, let’s take a whistle-stop tour of the challenges you’ll face.

The challenges of managing business creativity

Before you start breaking the rules of management, there are a few challenges to be aware of.

Are you an accidental manager?

Management is talked about often in creative businesses as a ‘necessary evil’ – by employees, and sometimes managers, too. This is because the world is full of accidental managers. A role on the management team is seen as the logical next step for people who have excelled. Talented people are promoted, sometimes against their wishes, to a managerial post with little guidance. Usually they’ve picked up the art of management from odd snippets of TV, films and examples of sometimes terrible management in their own careers. As a result, some default to an inconsistent, occasionally dictatorial, impression of what they think management should be. Or, they trend the other way: they’re everyone’s ‘best friend’ and are perceived as a useless pushover. It’s ‘The Peter Principle’, which states we’ll be promoted to the level of our incompetence. Of course, this is a disaster for the person being promoted. It’s also damaging for the company: ‘old-style’ management in a creative business is like fixing a delicate circuit board with a hammer.

But, if either of the descriptions above describes you, relax. You’re not alone. I’ve discovered through running management development programmes for many years that very few people are born as effective and enthusiastic managers. Use this book as inspiration to design your own learning journey to make it a bit easier and more fun. Management isn’t necessarily always unpleasant or difficult – it can be a rewarding adventure.

![]()

Are you an accidental manager? If so use The Spark to develop your own more effective and personalised management approach.

Why many businesses avoid being creative – most of the time

One reason managing for creativity is tricky is it’s not what most businesses are doing, most of the time. Businesses are often trying to exploit well-trodden processes and proven products to make money right now, this month, this year.

Even a creative business like Disney isn’t trying to be creative all the time. A good example is how Disney manages its global theme parks in comparison with how it runs its research and development teams in Burbank, California. Theme park cast members, as they are called, follow strict rules and ‘scripting’, whether they are playing Mickey Mouse, a Caribbean Pirate or Goofy. Deviation from character is frowned upon. This is because Disney executives want the customer experience to be the same high standard in any one of its theme parks whether in Florida, Paris or Tokyo. However, the ‘imagineers’ in Burbank, who are being challenged to dream up new rides, characters and storylines for the theme park experience, are not scripted. Their approach to day-to-day working life will be very different because their management challenge is the polar opposite to the theme park cast members. One is trying to capture Disney’s past successes and replicate them endlessly; the other is trying to forget the past to dream up something wild and new.

![]()

As a manager you need to make informed judgement calls on the balance of resources between ‘doing the day job’ (theme park cast member) and allowing the time and space to create the spark of new ideas (imagineer).

Creative people are hard to manage

Creative people are hard to manage because they naturally seek to ‘gold plate’ their work. Managed well this can lead to outstandingly satisfied customers. But a creative person’s sense of purpose and passion about finding something original may lead him or her to work so long on ‘getting it right’ that the business makes no profit. In many creative businesses in which I have been called in to help, unprofitability has been a major issue driven by the perfectionism of creative and technical specialists. They are also hard-wired to be unimpressed by your title and authority: what you do is more important than what’s written on your name tag. Finally, they’re more difficult to bribe with money. Salary and bonuses mean less to them than the majority of the population because the quality of the work and their colleagues is often equally, or even more, important.

Becoming an electric manager

When Carol landed her first job in the R&B music industry in London she knew she needed to learn the art of managing creativity – and fast. A talented amateur violinist, she’d staked a lot on reinventing herself as a record producer. For 10 years she’d been a successful City lawyer; but had become disillusioned after the credit crunch scandals. She’d landed a brilliant job. The downside: failing at the high-profile and respected Art4Profit record label would be a potentially terminal start to a new career.

She soon realised there was little point in throwing her weight around. As producer – the person responsible for bringing the creative team together to deliver the record – she was clearly as much a collaborator in the creative process as someone who could crack the whip. She realised she needed to embrace the fact that a recording studio is an ambiguous environment with no clear yardstick for ‘good’ or ‘bad’ quality, clear lines of authority or hierarchical control over the end product.

For the first week she felt ineffectual and all at sea. But then she had an insight. It was true that much was out of her control – but what was in it? By posing this question one night over a glass of wine she scribbled down the following list:

- Setting the vision and objectives: To make sure the album is delivered on time and to the right standard. My job is to make the success criteria for the album crystal clear – and to keep everyone on track when they start to stray from this.

- Who plays on what: I have the power to select and influence which musicians and artists feature on which tracks – so understanding where talented people will shine, and where they will bomb, is crucial to the success of this project.

- My managerial approach: A democratic, listening and facilitative style seems to work best. In this way I can ‘nudge’ the product to something that’s high quality – and also might sell some records!

Carol also had power to set deadlines. She experimented with forcing the pace of production but quickly found this was counterproductive and produced poor-quality results. She realised it was better to agree clear, reasonable deadlines from the start and allow the many different parties involved in producing a record – songwriters, publishers, artists, session musicians and personnel marketeers – space to be creative. She noticed if she allowed them a little time to mull over particular challenges they often arrived the following morning with an innovative solution.

As the months rolled by, Carol grew in confidence and proactively started to guide the creative output through ad hoc listening sessions in which the various teams she worked with played and then dissected ‘bad songs’ and ‘good songs’ to forge a common aesthetic for each album. But she was careful to allow space for the artists to experiment with their own sound and forge their unique contribution to each project.

When the final track was finished she met her former legal colleagues in the pub and tried to explain the art of creative management: ‘My job is to develop a shared purpose while still letting others apply their distinctive expertise. I like to think I operate at the “centre of the storm” without being too controlling, or the focus of attention. The satisfaction comes from helping others realise their unique talents and reach a collective goal. Fingers crossed: a hit record, we’ll see!’6

![]()

List the key success factors for managing creativity in your business or team. Then underline the factors that offer you the most leverage to beneficially guide the creative process.

Breaking the rules

Electric managers have to be thoughtful, nuanced and skilful in their approach. They need to develop higher levels of empathy and self-awareness than previous managerial incarnations. As Scott Cook, the co-founder of the US software company Intuit observes: ‘Traditional management prioritises projects and assigns people to them. But increasingly, managers are not the source of the idea.’7 People placed in a managerial position need to have the capability to choose when to ask for consistency; and when to allow team members to get creative. Managers need to break the management rules to encourage electric conversations:

| Management rule | Breaking the rule |

| The intention is to produce predictable, consistent results. | The intention is to deliver consistently; but managers need to check they are not inhibiting creativity. |

| Command-and-control approach: directions to ensure everyone in the business follows a prescribed path. | Guiding approach: support and encourage people to higher levels of awareness and responsibility for their actions. |

| Focus on telling: tell people exactly what to do and then monitor how they do it. | Focus on listening: clearly outline the brief, objective or mountain to climb and then listen to how the person might use their creativity to deliver. |

| Treat everyone exactly the same. | Observe individuals carefully and treat them how they like to be treated – and will respond to. |

| Focus on process and the desired result. | Offer scope to look at things in their own way. |

| Ask closed questions that have only three possible answers: ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘I’m not sure’. | Ask open questions that require people to respond with full sentences – to think and to engage. |

Managing the creative process

One of the key jobs for any manager in a creative business is to oversee projects; to ensure they deliver to the right standard as well as being on time and on budget. This may sound counterintuitive, bearing in mind creative businesses generally seek to relax the ‘rules’. But, whether it’s a bicycle being designed, a website being built, a movie or hit record being produced, management is always required. After nearly two decades of research into creative management, US academic Teresa Amabile argued that good ‘project management’ is one of the most important factors for encouraging creativity in business. Here are five principles of enlightened electric management to help you to avoid killing creativity:

1 Create clear project objectives

Invest time ensuring the brief for any creative work is detailed and specific about success criteria - but not the solution itself. Counterintuitive people are more creative when they have to solve problems within clear rules and objectives. The legendary Dutch footballer Johan Cruijff first showed off his innovative ‘Cruijff Turn’ in the 1974 World Cup. Instead of kicking the ball, he would drag it behind his planted foot with the inside of his other foot, turn through 180 degrees, and accelerate away from the defender. Cruijff would never have come up with this creative skill unless he’d been challenged by the limitations of playing inside the pitch touchlines.

When the brief for the project has been set, move the goalposts (and the touchlines) as little as possible. Kevin Roberts, CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi, describes how his agency provides an ‘elastic-sided sandbox’ for employees to play in. In other words, Saatchi & Saatchi offers clear focus – and just enough freedom to bend the rules if required.8 We explore the importance of this in Habit 8: Balance focus with freedom.

2 Match the right people with the right projects

Take care to recruit the right people to assignments which best fit their capabilities and interests. It is an electric manager’s job to make sure that people in the team achieve a good balance of personal challenge, learning and enjoyment from the work. Aardman executive chairman David Sproxton rates the ability to understand the capabilities of your employees, to ensure they are challenged properly, as a ‘highly important skill’. It is one of the major transitions of management to realise a good part of your focus now needs to rest with the abilities of others – and not yourself.

3 Manage deadlines carefully

A certain level of urgency is always present in business. It goes with the territory. ‘Time is money’, as the old cliché goes. And reasonable, genuine deadlines – delivering a proposal, being faster than competitors, meeting client expectations – can help to heighten ingenuity. But research shows there are two types of deadlines that are poison to creativity:9

- Unrealistic deadlines: constant, overambitious deadlines don’t lead to breakthroughs; they lead to nervous breakdowns and talent burnout. Creativity flows from situations where people can explore and play; when they have sufficient time and resources to do the job.

- ‘Fake’ deadlines: time limits invented by managers to artificially stimulate people to action don’t help; in fact they hinder people’s ability to work creatively. Not only are they ineffective, they destroy the relationship between teams and managers because they’re (rightly) viewed as manipulative.

If you fail to set realistic, honest deadlines you will encourage the famous response written by English science-fiction novelist Douglas Adams: ‘I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.’

4 Protect people in the maze

Imagine a giant maze.10 The sort of maze with evergreen hedges too high to see over. The maze represents the time a person or team spends trying to apply creativity to a problem. A bad electric manager stands at the edge of the maze with a megaphone shouting: ‘Get to the nearest exit; we need to deliver this project right now! And if you do manage to get out in double quick time, you’ll be in line for a bonus.’ A focus on a specific, speedy outcome backed up by juicy carrots such as cash bonuses encourage people to follow the most well-trodden path. You’ll get a result, but it won’t be very creative.

If you are trying to escape from a maze very fast they aren’t as much fun. In fact they are quite frustrating. But, if you are absorbed in solving the mystery of a maze, they’re enjoyable. Time flies. So, the role of a good creative manager is to pat the person or team on the back as they enter the maze – then to stand guard as they roam around inside. The hope is the person or team is motivated to explore the maze, to find interesting pathways and routes inside that are novel and valuable. To encourage this intrinsic, inner desire to crack the code, to unveil the mystery, to be creative, you stand guard at the exit to usher the team back inside if their ‘route’ is not up to scratch.

A good electric manager will also shield the person or team from the pressures of business life: impatient clients and carping from other parts of the business. Ben Kingsley, who played the lead in the 1982 biopic movie Gandhi, tells a story of how the director, Richard Attenborough, skilfully managed his anxiety during a crucial scene. There were hundreds of extras and an enormous crew standing by. The light was fading. Kingsley felt under enormous pressure. But he was struggling to get his lines just right. He recalls how Attenborough paused and whispered in his ear: ‘You have all the time in the world, dear boy.’ Kingsley nailed the line, Oscars all round.

Creative business managers ensure people and teams have sufficient time and resources to do the job of innovation properly. That means having time to explore, and to think protected from the ever-present need to deliver for customers and clients. John Cleese, the English actor, comedian and management commentator, puts it this way: ‘If you want creative workers, give them enough time to play.’

![]()

In your next project appoint yourself guardian of the creative maze as your team explore ideas and options.

5 Manage the process

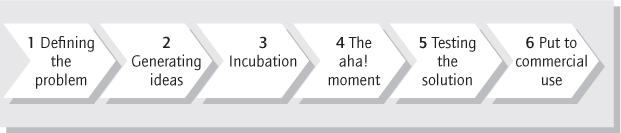

There are many versions of a generic creative process from thinkers going back nearly a hundred years. Here is the version I’ve designed as a good start for you to tweak and compare with your own team or business.

figure 2.1 The Spark creative process

By all means modify it to match how you work. By understanding the stages you can carefully calibrate your behaviour – what you do and say – to help rather than hinder idea creation. Here are some suggestions for the key milestones in the process – and what can do as a manager to add value.

| Creative stage | What’s happening | Management action |

| Defining the problem | Insight and analysis are used to engage with the issue – the search is on for helpful information. This stage is all about ensuring the team has a clear and tight brief to work with. | Ensure the team has a well-written brief and the problem or issue is clearly delineated. Make sure sources of inspiration and information are available so the team start thinking as broadly and creatively as possible. |

| Generating ideas | Divergent thinking is used to generate lots of different ideas. | Defer judgement until each idea has been fully explored with a ‘yes, and…’ approach. In reality, groups can self-consciously flip between ‘not judging’ and ‘judging’ ideas during this stage, as long as this is facilitated skilfully – that’s often the job of the manager – to bring in all the experience and expertise in the room. |

| Incubation | ‘Letting go’ and allowing the power of the imagination to work in the background. | Hold your nerve! Protect your people from too much interference while this stage runs its course. There may be a slack period when the mysterious workings of the unconscious, ‘secret brain’ take over. This might look like a waste of money to you (and, more problematically, to your boss or the client); but, clearly it’s not. Creativity often strikes when the problem is not front of mind. |

| The aha! moment | The moment when lightning strikes and a viable idea happens. | Don’t get too excited. Business people know this is just the start of turning the idea into something that can help the business or be commercialised. Often the so-called aha! moment is actually a long series of aha! moments, as a mediocre idea is challenged, refined and worked up into something better over weeks, months, or even years. |

| Testing the idea | Convergent thinking: Does this work to solve our problem or, more subjectively, is this genuinely a ‘good idea’? | Listen carefully to your analytical brain and your ‘gut’. Does this idea look right, sound right – and feel right? Creative leaders and managers have the courage to stand up for good ideas (and ‘good’ is always a subjective call) and kill bad ideas (ditto). |

| Put to commercial use | The idea or solution is implemented in the business. | This is innovation: the role of management is to mobilise coalitions of people to make the idea valuable inside or outside the business. |

![]()

Consciously choose when to intervene skilfully and when to step back tactfully during the creative process. Intervention opportunities include setting clear goals, keeping the team on track, matching the right people with the right projects and supporting the team with time and resources.

Understanding where ideas come from

“All great artists and thinkers are great workers, indefatigable not only in inventing, but also in rejecting, sifting, transforming, ordering.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, German philosopher

When I mentioned I was writing this book to a friend of mine who is a senior partner in a British law firm, she said: ‘Oh, creativity; we see that as a dark art that nobody properly understands’. My friend is like so many managers. They know creativity is important; but it’s shunted into the corner, as there isn’t the time or tools to understand it – let alone manage it. Creativity is a black box that you hope your employees go into every now and then. You’ve no idea what happens inside, but you cross your fingers they’ll emerge with a good idea.

If you see creativity as a bit of a grey area, you’re in good company. In the last century, scholars from the fields of psychology, education, philosophy, sociology, linguistics, business management and economics have disappeared into its mysteries and emerged with varying, and sometimes conflicting, advice. Even a brief survey of the ongoing arguments over where ideas emerge from could fill a dozen pages. I’m going to spare you the detail, and examine only the key questions for an effective manager within a creative business:

- How do ideas happen?

- What role does inspiration play?

- What role does good, old-fashioned hard work play?

These are crucial questions for an electric manager – here we’ll shed enough light on them to make your job easier.

![]()

Think about the last good idea that emerged from your team – how and why did it happen?

The mysteries of a hot shower

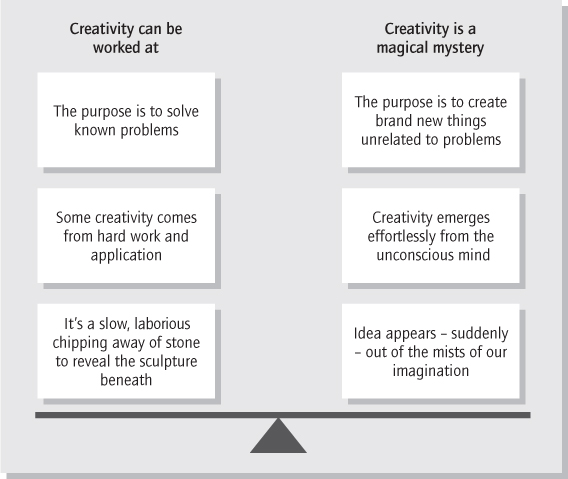

Some people argue the very idea of a creative process is like a unicorn or an honest politician: an intriguing concept that doesn’t exist in the real world. However, there is a creative process and it’s very useful for managers to understand it. There is still an ongoing debate over exactly what happens in the creative process and the relative importance of each stage. By briefly illuminating these contradictory viewpoints, I hope to provide you with something solid you can rely on to better manage the process of ideas happening in your business. To simplify things (and believe you me, it needs it) let’s weigh both sides of the debate.

figure 2.2 Weighing up the creativity debate

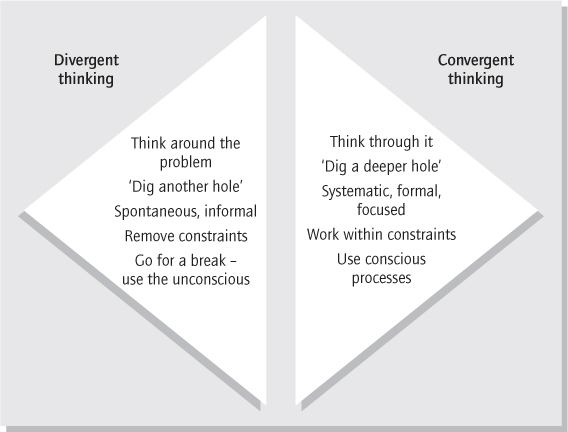

Another route to better understand the inherent tension in business creativity is through what psychologists call divergent and convergent thinking models.

- Divergent thinking: here creativity is about widening the scope and not judging them, because quantity of ideas will lead to quality of ideas later on.

- Convergent thinking : this involves carefully judging the quality of ideas and using analysis to narrow the scope down to a single ‘right answer’.

figure 2.3 Divergent and convergent thinking styles

The secret brain

The most heated arguments are over the role of our unconscious – the ‘secret brain’ – that works without us knowing. One side of the argument seeks to highlight its role in our personal creativity. Take, for example, 3M’s campus HQ in St Paul, Minnesota. There you might imagine red-eyed, industrious workers locked in dark conference rooms sweating over the next big thing. Actually, you would find people engaged in all sorts of frivolous activities from playing pinball to just taking a stroll. Their managers push them to take regular breaks because time away from a problem can help spark a moment of insight. This is because interrupting work with a relaxing activity lets the mind turn inward, where it can puzzle subconsciously over subtle meanings and connections (the brain is incredibly busy when daydreaming). ‘That’s why so many insights happen during warm showers,’ says Joydeep Bhattacharya, a psychologist at Goldsmiths, University of London.

My research and experience points to what most people know intuitively: when you’re pondering over something that requires creativity, there is sometimes a mysterious moment when ‘something happens’. At the start of my leadership programmes, I always ask participants when and where they benefit from their own personal aha! moments. The answers are, almost always, when the person has switched off from work: out jogging, on their bicycle, driving home and, yes, you guessed it: in the shower. Archimedes may have had his Eureka moment in the bath, but in the modern world many of us are at our most relaxed and subliminally sensitive when we’re standing in the shower. It’s the one time of the day when our brain can switch off. It’s there, and in other unguarded moments, that we can hear our own genius whispering to us.

As a business person, if I could diminish the role of mystery in creativity, I would. Let’s face it, the unconscious is the most unreliable employee of all time. It talks to you only in dreams and then in a coded language you don’t understand; it has deep urges, some of them, a little antisocial and distinctly sexual; and it reveals its work only when it wants too. The problem is this: I believe these spontaneous ‘aha!’ moments are the magic and mystery at the heart of a creative business. They have given birth to every patent, new product and successful new company ever known. The challenge for the electric manager is to live with that slightly unnerving knowledge.

Business creativity is not a case of crazy divergent thinking or disciplined, systematic thinking. It’s both. Both sides of the scales have weight. Creativity is a complex combination of blood, sweat and tears and effortless imagination and dreams. It’s a wonderful mystery, and also a (little) explainable. Imagination, the unconscious, whatever you want to call it, is involved; but then so are hours of solid, structured application to fully understand the area in which creativity is being used.

Sometimes creativity comes to us in the mists of a hot shower. But, when it doesn’t, we have to search it out. After surveying the scientific research into imagination, journalist Jonah Lehrer concluded: ‘The reality of the creative process is that it often requires persistence, the ability to stare at a problem until it makes sense. It’s forcing oneself to pay close attention, to write all night and then fix those words in the morning. It’s sticking with a poem until its perfect; refusing to quit on a maths question; working until the cut of a dress is just right. The answer will be revealed slowly, gradually emerging after great effort.’11 The classical composer Ludwig Van Beethoven is often cited as almost a cliché of effortless genius. But even the great man struggled with his music and often would make 70 different versions of a musical phrase before it was ‘right’.

The creative process needs both cavalier imaginative leaps and the remorseless grind of roundhead application and reality. This is why the advertising slang term ‘T-Shirts & Suits’ to distinguish between ‘alien creatives’ and ‘boring suits’ has stuck. The phrase acknowledges that it may not always be the same people bringing these qualities to the party. Deborah Baker, HR director at Sky, puts it this way: ‘I believe in balance. You need to have lots of creative people – and lots of people to check their ideas and ensure they work.’

An electric manager certainly has to understand and deploy both approaches. The creative process is messy, paradoxical and difficult to explain because creative people, teams and businesses have to shuttle constantly between divergent and convergent modes of thinking. Creative academic Chris Bilton writes: ‘The argument here is not that creative thinkers need to release themselves into a meditative state (the bath), any more than they need to lock themselves into an inexorable process of analysis (the workshop). Instead they need to find a way of changing gears mentally.’12

![]()

Start to better understand your own personal creative process. For example, where and when do you have your ‘aha!’ moments of insight?

Electric conclusion

To facilitate, support and inspire the creative process, electric managers need to rip up the normal managerial play book and take a distinctly fresh approach. It is tricky because it involves unlearning some of the normal rules of management. At its heart is being constantly aware of when management is useful in the creative process – and when it’s not. It requires the sort of self-awareness and bravery normally associated with the leadership attitudes described in the next habit.

CLEAR steps to change

Communicate

Ask three people to explain your company’s creative process – and compare what they tell you. What are the differences – and similarities – in how they map it out?

Learn

Sit down with the key people in your team and draw up:

- your creative process: create a version of what it is now – and ‘what it should be’;

- your current management interventions: these are the processes and practices you use to monitor activity and drive results: examples include time sheets, six-monthly appraisals, sign-off for investment, how you run your regular management meetings, ad hoc ‘check-in’ meetings and internal communications.

Energise

Are these management processes and practices empowering people around you to use their initiative, speak up with new ideas and seek to improve the way you work as a business? Or, are they killing creativity? Are your creative process and management interventions good, bad or indifferent? How should they develop? Design a series of sensible changes that will make the biggest difference. Don’t implement them all at once. Start small; you can continue the improvement process based on success.

Act

Implement some changes to how you manage your team and business based on the thinking above. Make sure you communicate the reason behind these to those not involved in the initial brainstorming group.

Respond

After six weeks, get the original group back together and ask: What worked? What didn’t work? What else needs to change for us to work more creatively?

1 Creative Quotes and Quotations on Managing [online]. Available at: <http://creatingminds.org/quotes/managing.htm>.

2 Murphy, S., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme at Sky Grant Way, Isleworth on 29 August.

3 Kiechel III, W., 2012. The management century. Harvard Business Review, November.

4 Taylor, F.W., 1911. The principles of scientific management. New York and London: Harper & Brothers.

5 Sutton, R.I., 2001. The weird rules of creativity. Harvard Business Review, September, p.96.

6 Long Lingo, E. of Vanderbilt University in Tennessee and O’Mahony, S. of the University of California reported in Amabile, T.M. and Khaire, M., 2008. Creativity and the role of the leader. Harvard Business Review, October. Available at: <http://hbr.org/2008/10/creativity-and-the-role-of-the-leader/ar/1>.

7 Amabile, T.M. and Khaire, M., 2008. Creativity and the role of the leader. Harvard Business Review, October. Available at: <http://hbr.org/2008/10/creativity-and-the-role-of-the-leader/ar/1>.

8 Hytner, R., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme at Saatchi & Saatchi, London, 26 September.

9 Amabile, T.M. and Khaire, M., 2008. Creativity and the role of the leader. Harvard Business Review, October. Available at: <http://hbr.org/2008/10/creativity-and-the-role-of-the-leader/ar/1>.

10 The concept of ‘The Maze’ is featured in Amabile, T.M., 1998. How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, September.

11 Lehrer, J., 2012. Imagine: how creativity works. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 56.

12 Bilton, C., 2007. Management and creativity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 9.