Habit 4

Become a talent impresario

How to fill your business with creative talent

You’ll learn:

“It’s about getting the best people, retaining them, nurturing a creative environment and helping to find a way to innovate.”1

Marissa Mayer, CEO of Yahoo!

In 1991 Philip Chin and his wife Joanna founded Langland in their dining room with no money, a printer and a borrowed Apple Macintosh computer. They based the business away from the bright lights of London in sleepy Windsor, in Berkshire. It’s fair to say that Windsor isn’t a renowned creative hotspot; it’s more famous for being home to a royal castle and Legoland. Despite this handicap, by 2007, the couple had built the agency to a very respectable size.

Langland specialises in advertising campaigns on behalf of pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription medicines to healthcare professionals. Healthcare advertising is a niche category which, to put it politely, is viewed by the rest of the advertising industry as a little backward. ‘Back in 2007, it was grim. The standard of creative work in the industry was pretty rubbish,’ said Chin. Laughing, he added: ‘The talent pool is a bit “in-bred”, and the quality of creative work lags well behind that seen in consumer advertising. To make a career, you don’t generally come to work in healthcare; you’re sent.’ 2

But, amid the uninspiring ads for angina tablets, thrush cream and flu jabs, the couple sensed an opportunity. After all, why did they have to conform to low standards? Why not use creativity to transform their business – and the image of the healthcare advertising sector? The tenure of a talented interim creative director, Gordon Torr, provided the perfect opportunity to drive change. Because Langland had been well run they knew they had the cash reserves to invest. Chin said: ‘For people to be creative, a business has to be secure. People can’t be worried where the next client, or pay cheque, is coming from.’ They had also built a solid team, with an empowering culture based on shared values. But they knew there was a missing ingredient. They needed what Chin describes as a ‘creative catalyst’. They upped the salary budget so they could bring in someone working from ‘outside the healthcare village’, and went looking. They found Andrew Spurgeon who had previously been appointed as the youngest creative director in the global JWT advertising agency network.

Chin reflected: ‘We had all the ingredients already. We had people with talent, but it was sort of dormant. Andrew came in and worked to bring the talent out. He improved the ones that were average – to good; and those that were good – to great.’ More discipline was introduced into the creative process. Three creative principles – simplicity, surprise and empathy – were created and used to judge every piece of creative work. ‘Creativity is so subjective,’ Chin argues, ‘You need to be able to agree a benchmark. At the same time we also improved our standards of production. It’s all very well having good ideas; but you also need to execute them brilliantly, with craft skills of the highest order.’3

The results of this creative inflection point have been spectacular. In four years Langland transformed itself into ‘the world’s most creatively awarded healthcare advertising agency’. In 2008, the business won just 24 awards; 4 years later, they won 103. ‘It became a bit embarrassing,’ Chin ruefully admitted. ‘One awards night we were up against the Big Five global advertising agency networks and we walked away with over half of the awards.’ At the same time, Langland was recognised as a great place to work and this award was repeated two years in a row.

Leveraging the value of its existing talent through a catalysing new hire has meant that commercial success has accompanied creative excellence. Whilst the rest of its industry shrank, or kicked its heels through the worst downturn in living memory, Langland grew revenues by 45 per cent. Inspired by their purpose statement – ‘To be famously creative, effective and profitable’ – Chin and Joanna are now focused on expansion. But they’re sticking to the formula that’s worked so well. Chin concluded: ‘It’s about talent. Creative businesses are people businesses. It’s about relationships. We are now focused on developing our talent to take us forward.’

Has your rocket got the right fuel?

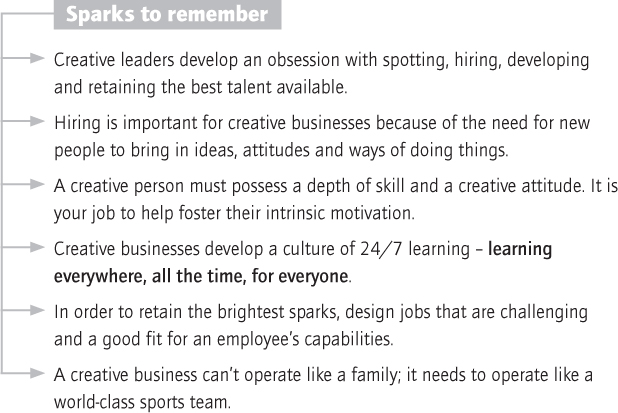

Without the right talent on board, a creative business is like a rocket without fuel. Leaders need to be able to find people with ability, encourage them, develop them, and offer them an environment in which they can flourish. It’s the difference between success and failure. One thing’s for sure: if you don’t understand how people tick, you can’t understand how creative business works. Like a TV talent show judge, creative leaders need to be passionate and informed about discovering new talent – and decisive with those that don’t make the grade.

![]()

Normal businesses can afford to be customer-focused. Creative businesses have a triple focus: the idea, the customer and the talent.

A-list talent: small differences, big money

After studying commercial creativity in a wide variety of settings – the visual and performing arts, films, theatre, sound recordings, and book publishing – Harvard Professor Richard Caves came to a solid conclusion: talent drives success. As a renowned economist, Caves bought a distinctly analytical, scientific approach to identifying value drivers within creative businesses. He argues that even small differences in talent will lead to huge differences in financial success. He calls this economic rule the A-list/B-list factor.4 For example, a movie script placed in the hands of an A-list film director like Steven Spielberg, the master storyteller behind E.T., Jaws and Saving Private Ryan, would produce Movie A. If the same script is directed by a B-list director with a little less talent, we could compare Movie B to Spielberg’s Movie A. Even though the B-list director might be just as experienced, the finished product will not be separated by a few small steps. Movies A and B will be a huge leap apart in class. This is why Hollywood stars like Tom Cruise, and global sports talent like Cristiano Ronaldo, command fees measured in tens of millions of pounds. Meanwhile, actors and ordinary footballers, who are still way more talented than 99.9 per cent of the planet, struggle by on minimum fees and waiting tables. Small differences add up to huge chasms in value. The agents and managers of Cruise and Ronaldo see the difference between A-list and B-list talent. In the same exponential way talent impacts the fortunes of any creative business.

The bozo explosion

Apple’s late CEO Steve Jobs was well aware of the crucial role played by talented people. Biographer Walter Isaacson observed that Jobs tolerated only what he called A players. Isaacson wrote: ‘Jobs was famously impatient, petulant, and tough with people around him. But his treatment of people, though not laudable, emanated from his passion for perfection and his desire to work with only the best. It was his way of preventing what he called “the bozo explosion” in which managers are so polite that mediocre people feel comfortable sticking around.’5

I wouldn’t advise any leader to use Steve Jobs’ managerial approach as a template. Copying a leadership myth is a dangerous game. He was undoubtedly successful; but he was also a complex, idiosyncratic, contradictory character. Working out which factors of his leadership style were positive and negative is difficult. His leadership abilities may have been overestimated – Apple may well have achieved stellar success despite some of his questionable tactics. We’ll never know for certain. One thing’s for sure: he somehow managed to engender loyalty in his top people; they tended to stick around longer than executives at rival companies with a better reputation for being nice.6 Clearly he understood the need for hiring the best people: the likes of John Lasseter, Jonathan Ive and Steve Wozniak. And, his preoccupation with talent is a legitimate creative business habit you can seek to emulate.

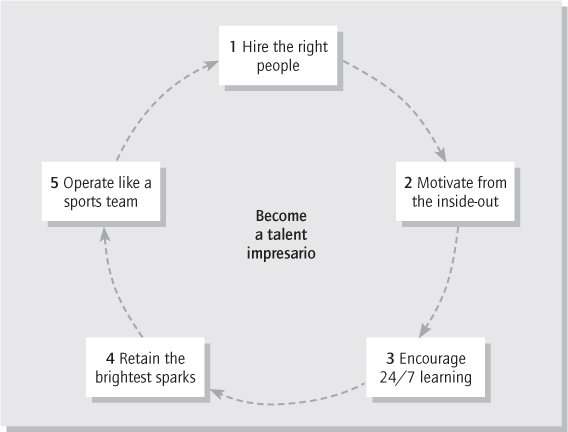

It’s obvious that talent equals creative success. The how is less obvious; that’s what this chapter is about. An old-fashioned word for someone who brings people together to put on a theatre production is an impresario. This habit highlights five steps to take to become a talent impresario: to have an obsession with hiring, developing and retaining the best people.

The five steps of the talent impresario habit follow the talent journey from outside your business to making an impact inside it. If enacted consistently, they create a virtuous circle to help you win the war for talent.

figure 4.1 Five steps to becoming a talent impresario

1 Hire the right people

“Beware of sad dogs that spread gloom.”

David Ogilvy, founder of Ogilvy & Mather

Hiring the right people is a critical discipline for a creative business to get right. Jim Collins, the author of Good to Great, the iconic business book about lasting success, puts it this way: ‘You absolutely must have the discipline not to hire until you find the right people.’ Former global creative director for the advertising agency JWT, Gordon Torr, who I mentioned previously when he worked with Langland, has written a book about managing creative people. He offers a simple maxim: ‘Hire the best talent and let them get on with it.’ It’s not quite that simple – but his view highlights the importance of talent on the front line. Here is another passionate plea from the global advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather’s Guide to Recruiting Talent:

“There isn’t a single activity in our business more important than recruitment. It determines whether or not the agency will remain healthy. Every act of recruitment that brings in someone better – better than before or better than average – makes it more likely that we will be successful. Each time we bring in someone who is not good enough, it makes it more likely that we will fail. And it works like a disease with a multiplying effect – because a below-average individual will always, in turn, bring in others who are below average. And so on! Until, in a matter of a few short years, the agency turns from energetic to flat and from vibrant to sad.”

How to spot creative people at interview

All people have the capacity to be more creative. But, like sprinting, solving crossword puzzles or cooking a soufflé, some people will be born with more aptitude than others. So, while creativity lurks inside all of us, it makes sense to hire people who’ve got more than their fair share in the first place. Hiring the right people is a lot cheaper than trying to mould them into the right stuff after they have ripped open their induction pack. Here are a few traits you should be looking for in a person’s CV, testimonials and at the interview stage:

- Their relationship to financial reward is more complex: The Harvard economist Richard Caves calls this propensity to be more interested in the work than the money: ‘art for art’s sake’. It has been shown in numerous studies that money does not necessarily buy more creativity. Creative people will be fascinated by how they can develop their own skills, the quality of the clients and projects they have the opportunity to work with. They will be less interested in salary and rewards than people with less creative drive. But don’t take this to mean they come cheap. They know their worth and will expect market rates just like anyone else.

- They define their identity as creative, rather than corporate: Research shows that for creative people their talent is central to their identity. They are defined by their passion and perfectionism. They may rank their creative identity above being a member of your team. Their loyalty is to their own development and the work – not to you. One way to help them sign up and stay with your business is to ensure they can connect to other clever, creative people inside and outside your organisation. Sell this as a benefit.

- They are not impressed by corporate hierarchy: They know their worth in the talent marketplace, and often are organisationally savvy. They relentlessly interrogate team leaders with difficult questions. Once on board they will expect instant access. In response to this tendency Sir Martin Sorrell, founder of the global advertising agency network, WPP, has developed a notable speed of response to emails from his thousands of staff – normally within hours.

- They will challenge you: Stanford University management and engineering professor Robert Sutton studied creative businesses and concluded that managers should be searching for a quality that makes them feel just a little bit uncomfortable. He urges managers to hire what he describes as ‘low self-monitors’. He writes: ‘People who are especially insensitive to subtle, and even not so subtle, hints from others about how to act. For better or worse, low self-monitors are relatively unfettered by social norms. These mavericks and misfits can drive bosses and co-workers crazy, but they increase the range of what is thought, noticed, said, and done in a company.’ So you need to assess if the person has talent, of course – but also a certain attitude and a little determined ignorance of ‘the right way to do things’. Our natural urge is to hire people like us; but they also need to have the strength of character to challenge the status quo to support a good idea. There is more to a creative business than building a be-like-me cult.

![]()

Ask interviewees to explain the ideas and innovations for which they have been responsible in their previous jobs or university career. If they don’t respond with passion and enthusiasm, and some compelling examples, they haven’t developed a creative attitude and track record. Also, engineer a chance for them to candidly disagree with your opinion to check how independent-minded they are.

Making waves

Hiring is so important because of the greater responsibility placed on new entrants in a creative environment. Normal businesses interview candidates with an emphasis on fitting the right person to the right job. Creative businesses are hoping new people will bring in new ideas, attitudes and ways of doing things. A senior executive in a toy company tells of the challenge of hiring people who ‘think like us’ – but also retain the ability to point out what’s wrong with existing products. She said the behaviour of new creative employees ‘makes us hate them’; but ruefully admitted their criticism is vital as it leads to new toy ideas.

It took 15 years of frustration, perseverance, and over 5,000 prototypes for the British inventor James Dyson to launch the first vacuum cleaner under his own name. Within 22 months it became the best-selling vacuum cleaner in the UK. The company now designs and manufactures hand dryers, bladeless fans and heaters – selling machines in over 50 countries and employing 3,000 people worldwide – with revenues of over £1.2 billion and profit margins near 20 per cent.7 Dyson has prided himself on delivering products that work in different and better ways. The same goes for the management of the business. He believes one reason his company invents successful products is that it employs a high proportion of graduates straight from university. He comments: ‘They are unsullied. They have not been strapped into a suit and taught to think by a company with nothing on its mind but short-term profit and early retirement.’8 He adds: ‘Sometimes breaking convention creates a better way…it’s these bright young minds that offer a glimmer of the engineering stars of the future.’9

![]()

Don’t hire people because you think they’ll swim with the tide. Hire them because they’ll create waves.

Yin and Yang of hiring

Like every other factor in creative business, hiring involves managerial paradox; you having to balance the yin and the yang to get the right result. On the one hand you want to hire people who are creative mavericks who might make waves from time to time. On the other you want them to buy into your company values and purpose – and be able to display sufficient people skills to collaborate successfully with others.

I once visited the UK headquarters of the US games developer and publisher Electronic Arts (EA) to meet with executive vice-president David Gardner. Gardner joined what was a fledgling West Coast company as a teenager in 1983. He was entrusted with setting up their European operations in London just four years later. He spoke affectionately of the stringent recruitment policies the business had in its early years in California. New people coming into EA in the early 1980s didn’t meet just one or two people – they were interviewed by everyone in the company. Gardner explained this was deemed necessary to find the ‘right kind of people’ who fitted EA’s creative culture.

![]()

Balance the Yin and Yang of hiring.

- Yin: Find people who will challenge the status quo.

- Yang: Hire them if they’ll sign up to your values.

You need a little chemistry with colleagues. History is littered with creative scientists, producers, designers, sportsmen and others who have flourished within one organisation and quietly died in another because of a lack of fit. London Business School Professor Lynda Gratton researched the factors that produce cooperative teams and found parts of the hiring process were crucial.10 She recommends managers should:

- check if people are cooperative when you hire them;

- design the induction process so cooperation and relationship-building are seen to be important;

- encourage peer-to-peer working – emphasise no one can do it on their own and create easy structures and processes to make it possible.

![]()

Ask candidates how they’ve collaborated in the past. Listen carefully for how they describe the contribution of their colleagues. If it’s all about them, thank them politely and show them the door.

2 Motivate from the inside-out

“The happiest thought of my life.”

Albert Einstein (referring to the moment when he ‘discovered’ relativity)

How do you motivate someone to be creative? It is a central question for a business aspiring to deliver innovation. Harvard Business School’s Teresa Amabile is one of the world’s most respected authorities on business creativity. Bringing together decades of rigorous psychological, sociological and business fieldwork, her words should act as a stark warning: ‘There can be no doubt: creativity gets killed much more often than it gets supported.’ For the most part, this isn’t because managers have a vendetta against creativity. They understand the value of ideas. Creativity is always undermined unintentionally: usually in the pursuit of ‘no-brainer’ business goals such as coordination, productivity and control.

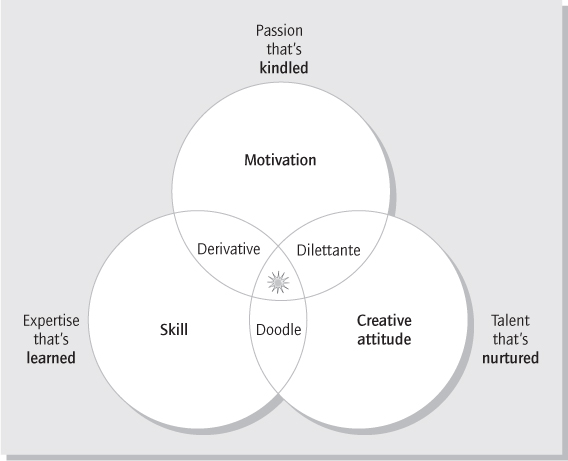

To avoid killing creativity, leaders need to understand the three crucial elements that Amabile’s research consistently finds high-performing creative businesses encourage in their people:

- Skill: Founded on technical, procedural; and intellectual expertise. Being good at a certain skill - achieving mastery in it - is the minimum requirement for commercial creativity. This is your craft: from editing video to mining iron ore, designing mobile phones to providing legal advice, farming pigs to running health clubs. And, of course, the broader your expertise, the larger the space you have in which to play: to explore and to solve problems.

- Creative attitude: This is your talent, or how flexibly and imaginatively you approach problems. For example, a bioscience researcher who is happy to disagree with colleagues is more likely to find innovative solutions. It will also help if he or she has the ability to be doggedly determined. You are born with talent. But you can maximise it by examining and developing how flexibly and doggedly you tackle problems.

- Motivation: This is how passionate you are to be creative. Skill and attitude are an individual’s resources for coming up with new ideas. Motivation determines what he or she will actually do.11

figure 4.2 The three crucial elements that all good creative businesses encourage in their people

- Derivative Motivation + skill produces derivative work – products and services based on other people’s ideas. For example, think of those endless, clichéd Hollywood films you’ve sat through each summer or some of the songs and artists produced by X-Factor-type TV shows. Lots of motivation, lots of skill, but the end product is truly tedious because of a lack of creativity. The end product fails to move you emotionally.

- Dilettante Motivation + creativity produces interesting work, but it’ll be amateurish by comparison to those who have achieved mastery of a particular domain. Dilettantes are creative in their spare time. For example, think of those millions of home-made DIY YouTube videos that are intriguing but miss the mark because the production values and storytelling are poor.

- Doodles Creativity + skill produces aimless bits and pieces. I once ran a strategy workshop for the whole leadership team of Aardman Animations, which included the world-famous ‘claymation’ director Nick Park. At the end of the session I asked to see Nick’s work pad. He turned it around and showed me the most incredible doodles of his famous characters: Wallace & Gromit. To transform doodles into the sort of Academy Award and box office success the Wallace & Gromit films enjoyed, you need to add motivation to spend countless hours on the hard work of creative production.

When skill, motivation and creative attitude are brought together – at the centre of Figure 4.2 – an individual will operate in a business environment to the peak of their abilities to deliver creative and innovative ideas.12

Inner and outer motivation

Not all motivation is created equal. There are two types:

- Carrots and sticks motivation: This is what psychologists call extrinsic motivation because it comes from outside a person. It is the motivation driven from what your business can do to bribe or threaten you. There are lots of carrots: promotion, higher wages, bonus payments, stock options – and various perks from a better office to a boarding card for the company jet. The sticks are familiar too: disdain, demotion and dismissal.

- Inner motivation: This is called intrinsic motivation because it comes from inside a person. It’s the individual’s innate passion for certain activities and challenges. CEO of Yahoo! Marissa Mayer once said: ‘Geeks are people who love something so much that all the details matter’. It is vital, of course, because it’s the difference between loving or hating your job.

Enormous amounts of time and money are expended to motivate employees to be creative. Sadly, much of it is wasted because traditional management thinking is obsessed with carrots and sticks. Extrinsic, external motivation doesn’t prevent people from being creative; but above a certain level it doesn’t help either. It can’t prompt people to be passionate about their work; but it can lead them to feel bribed or controlled. This isn’t an opinion, by the way. It’s fact. It’s been established beyond doubt through multiple and robust psychological experiments over many years.13 People drawn to creative fields are driven by a higher purpose than money: challenge, learning, achievement and peer recognition.

So, encouraging inner motivation is far more successful in delivering creativity. Nobody wants to be a starving artist. And you do need to pay a certain level of remuneration: market rates or, ideally, slightly above. Essentially, you need to take the issue of personal finance ‘off the table’. At that point, the research shows the link between cash paid and creativity delivered is broken.

![]()

Intrinsic – or inner – motivation is a complex mixture of a person’s interests and the environment in which they work.

Reward timing

External rewards can work – and timing plays a big part in how much. Management author Daniel H. Pink distinguishes between what he calls ‘if, then’ rewards and ‘now, then’ rewards:

- If, then rewards – If you do this, then you will be rewarded by the company: these guaranteed performance-linked bonuses are less effective as people take them for granted and game the system in order to receive them – ironically, crowding out the naturally occurring intrinsic motivation.

- Now, then rewards – Now you’ve performed well, then there will be a reward: this is the unexpected treat, such as taking your team out for dinner at the end of an assignment. It works well for creativity as it does not get in the way of a person’s intrinsic motivation to be creative.

Too much money reduces creativity

Psychological research stretching back to the 1930s clearly demonstrates, above a certain level, carrots not only don’t work, they actually reduce the urge to be creative. Pink argues: ‘For artists, scientists, inventors, schoolchildren, and the rest of us, intrinsic motivation – the drive to do something because it is interesting challenging, and absorbing – is essential for high levels of creativity. As the economy moves toward more right-brain, conceptual work…this might be the most alarming gap between what science knows and what business does.’14

As well as reducing creativity, carrots and sticks have other deadly flaws. They can:

- diminish performance;

- crowd out good behaviour;

- encourage cheating, shortcuts and unethical behaviour;

- become addictive;

- foster short-term thinking.

‘If, then’, external motivation works well for people in repetitive, process-driven jobs, when the work is what psychologists call algorithmic – that’s when tasks are routine, mechanical and have a certain obvious logic to them (jobs like picking raspberries, stuffing envelopes or making sales calls. Carrots then offer a route to boosting performance and application. But the best way to reward creativity is with a fair basic salary, with great health care and other benefits, which help to remove unnecessary distractions, and intelligently applied ‘now, then’ rewards. These rewards can range from a box of doughnuts or a few rounds of drinks to a special night out or a weekend away – or something even bigger. Using the indisputable findings of psychological researchers in your approach to compensation doesn’t just make sense in terms of encouraging the right sort of attitude and behaviour; it’s probably cheaper.

Collective rewards

An excessive reliance on cash bonuses can also have other unintended consequences. London Business School management professor Lynda Gratton’s research into business innovation hotspots shows creative companies tend to favour collective, rather than individual, rewards for a good reason. Individualised, highly competitive remuneration acts as a roadblock to a collaborative culture. She writes: ‘It is clear from the research into hotspots that team-based collective rewards do not themselves encourage cooperation. However, they do have the effect of removing the barrier erected by individualised rewards. In a sense, they are neutral rather than positive.’15

![]()

Make a note in your diary to spring a surprise on your team at the end of the next big project. If you find it difficult to dream up interesting gifts, find someone in your business that can help. Remember the Christmas present concept: ‘It’s the thought that counts’.

3 Encourage 24/7 learning

Finance director: “What happens if we invest in developing people and they leave us?”

Managing director: “What happens if we don’t – and they stay?”

Anon

Most businesses are not able to corner the talent market, however hard they try. If hiring and motivation are steps one and two in the talent journey, step three is helping a person to learn. Insatiable curiosity is a key element of a creative culture. Founder of the advertising agency Ogilvy & Mather David Ogilvy made learning the bedrock for his company: ‘We help them make the best of their talents. We invest an awful lot of time and money in training – perhaps more than any of our competitors.’

After the hit CGI movie Toy Story had firmly put Pixar Studios on the map, the leaders Ed Catmull and John Lasseter realised one way to sustain success was to create world-class talent development opportunities. They wanted to help new people and veterans expand their horizons. This was inspired by a famous memo written by Walt Disney 50 years earlier. Disney wrote: ‘I think we shouldn’t give up until we have found out all we can about how to teach these young [people] . . . there are a number of things that could be brought up in these discussions to stir imagination, so that when they get into actual animation, they’re not just technicians, but they’re actually creative people.’

Catmull and Lasseter got hold of this ancient Disney memo and the result of their discussions was Pixar University (PU). ‘PU’s mission is to integrate learning into the lives of Pixar’s employees through classes on everything from self-defence to drawing. The company encourages employees to dedicate up to four hours of every single week to their education. Pixar’s Randy Nelson, made the founding dean of PU, said: ‘The skills we develop are skills we need everywhere in the organisation. Why teach drawing to accountants? Because drawing doesn’t just teach people to draw. It teaches them to be observant. There’s no company on Earth that wouldn’t benefit from having people become more observant.’16

![]()

Set up a regular monthly creative session where people can come along with their work and new ideas.

At the heart of Pixar is an idea: ‘art as a team sport’. In practice this means people are encouraged to share their ideas and accept feedback without worrying about failure. Now the president of Walt Disney and Pixar Animation Studios, Ed Catmull said: ‘Everyone at the company will tell you there are no bad ideas at Pixar, even if they don’t end up in the movie.’ To assess your own development programme, you could do worse than compare its objectives to the collaborative ideal of the Pixar University. Pixar focuses on developing four basic proficiencies in people across the business:

- Depth: A mastery of one area needed by the business – anything from drawing to the complex programming required to make a Pixar movie. This is the ‘skill’ element highlighted in the section on motivation above.

- Breadth: A wide array of experiences and interests that give you the ability to explore things from different perspectives. This is about developing a creative attitude.

- Communication: The ability to truly listen; as well as to focus on the person across the table to make sure feedback has been truly heard.

- Collaboration: The ability to respond to others’ ideas with ‘yes, and . . .’ rather than ‘no, that won’t work’ or ‘this is better’. The ‘yes, and’ approach is practised in many creative businesses, including the British-based advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi.

![]()

Walt Disney used to say each person in the company has to be able to ‘plus’ the ideas of others to the make them bigger and better. Plussing ideas and a ‘yes, and’ approach are both in the spirit of this book’s central idea: electric conversations.

Pixar people are encouraged to be emotionally secure enough to make those around them look good. The company believes that their ideas – wonderful stories – will only come to life in the hands of interested people. They value this quality of being interested over merely being interesting. Interested people want to ask another question, to go even further to get to the best solution, to stay all night to make a project happen. It’s a trait, of course, of being intrinsically motivated.

![]()

Here are some good questions for the people running your learning programmes:

- Are we seeking to create a ‘learning habit’ in our people?

- Do our programmes cover creative business necessities, such as mastery of key skills, developing a creative attitude, communication, collaboration and the creative process?

- Are our training and development programmes aligned with our strategy? Will they help us to become a more creative and innovative organisation?

It’s about attitude

People development is not just about skills and knowledge – it’s about attitude. And attitudes start from the top. This was something Alessandro Carlucci, the CEO of Brazil’s Natura Cosméticos, realised after the business floated on the stock market in 2004. Carlucci faced a massive challenge: the whole future of the company was being threatened by the competing agendas of senior managers. His solution was to reorganise the executive committee, unify the team around shared goals and explicitly ask them to stop the turf wars.

![]()

A cheap alternative, or adjunct, to classroom-based learning is the mentoring of new employees by more senior executives. Research shows that mentoring has a positive impact on performance as well as encouraging a cooperative mindset.17

To help them see the bigger picture, each executive was asked to commit to self-development – to embark on a personal journey with an external coach. Carlucci explains: ‘It’s a different type of coaching. It’s not just talking about your boss or subordinates but talking about a person’s life history, with their families; it is more holistic, broader, integrating all the different roles of the human being.’ One of the senior executives involved, Roberto Pedote, Natura’s senior vice-president for finance, IT and legal affairs, said: ‘I think that the main point is that we are making ourselves vulnerable, showing that we are not supermen, that we have failures; that we are afraid of some things and don’t have all the answers.’

![]()

24/7 learning goes further than paint-by-numbers development approaches. It is about inspiring a prevailing attitude that every brief, project and meeting is an opportunity to learn something new.

Six years after the flotation, Natura Cosméticos grew by 21 per cent in a single year. To encourage the collaborative mindset more widely, coaching was also offered to Natura managers.18 Carlucci asked everybody to work together to make something bigger and better than their individual fiefdoms.

![]()

Encourage 24/7 learning. Blend different strands together including on-the-job development, group programmes, coaching, appraisals, 360-degree feedback, psychometric assessments and interactive online resources

4 Retain the brightest sparks

Think of this: for every employee who leaves, it costs about 12–18 months of their annual salary to replace them. The reason it is so expensive is that the business is hit with a tsunami of paperwork and time to say goodbye to the leaver; as well as recruiting, onboarding and development costs for the person coming in. Meanwhile, harassed managers spend valuable time juggling the transition and unfamiliar work patterns. The worst outcome is if the gap in experience and talent caused by the departure of a key person causes quality to fall and creates unhappy customers.19

Retaining the right people is always a core capability for a talent-driven business. You need to strike a balance between challenge and support.

- Too challenging: Even the best people will burn out and leave.

- Too supportive: And the best people may still leave – because they don’t feel stretched. Those people who are left are happy to coast. They may have lost all passion for the work and have become stale and uncreative. Ironically, these are the people who would benefit most from a new challenge; but they stick around. After all, nobody likes to get out of a warm bath.

You need to hold on to the best people, those of most value to your business. The global management consultancy Hay Group warns businesses face a talent exodus as the global economy recovers. So, why will talent stick around in your company?

![]()

Hold on to your brightest sparks by keeping them fresh and challenged. Diary a six-monthly or yearly reshuffle to rotate good people on to new jobs or high-profile projects.

Design challenging jobs

A study of 20,000 employees asked: ‘Why do you stay in your job?’20 Guess what? ‘My wage packet’ or ‘Getting a raise’ didn’t make it into the top six most popular replies. The prime reason to stay in a role was ‘job-interest alignment’.21 Translated from HR speak, that means people tend to stay if they’re offered a challenging and interesting job with sufficient opportunities for learning and development – as well as a close match between their capabilities and what they are being asked to do. They also want to be empowered with sufficient authority to match their responsibilities.22 Key factors in numerous staff retention studies are:

- Confidence in the quality of management: Your employees must view the business as being well managed - and heading in the right direction.

- Quality of co-workers: People want to feel they are working with good people (at least as good as they are).

- An environment for success: Processes must allow them to perform – red tape mustn’t get in their way.

- Collegial work environment: Not surprisingly, people love working in a culture in which they are respected and allowed to work collaboratively with others.

While financial compensation doesn’t figure in the reasons to stay, it does come out as the number one reason to leave, presumably for a company that isn’t taking advantage of them. Fairness is the key: people need to feel there is at least a reasonable exchange taking place between what they are asked to put in and what they are allowed to take out.

![]()

Match people with the right challenging job at the right time in their development. It helps to achieve a psychological personal state of flow, which is a proven way to boost happiness at work (flow is explained in Habit 1: Start an electric conversation).

5 Operate like a sports team

When the HR team at Netflix uploaded a simple PowerPoint document explaining the company’s revolutionary talent management policies, they probably didn’t expect the slides to be downloaded more than 5 million times. There’s a good reason for all the interest: the US provider of on-demand internet streaming media has enjoyed spectacular creative and commercial success. In 2013 alone the company’s stock price more than tripled and its US subscriber base grew to nearly 29 million.23 Netflix tries to hire the best, like anyone else. But, unlike other companies, it also practises a policy of ‘tough love’, which the founder and CEO Reed Hastings describes as: ‘Adequate performance gets a generous severance package’. In other words: deliver the goods, or you’re out.

Hastings asks managers regularly to use the ‘Keeper Test’. This is one of the questions: ‘Which of my people, if they told me they were leaving in two months for a similar job at a peer company, would I fight hard to keep at Netflix?’ Employees are also encouraged periodically to ask their manager a potentially awkward question: ‘If I told you I was leaving, how hard would you work to change my mind to stay at Netflix?’ Netflix is manic about high performance: it estimates in routine procedural work the best people are twice as good as average people. In creative work it finds the best are ten times better than average.

![]()

Research at Netflix shows in creative work the best people are ten times more effective than average performers. Try the ‘Keeper Test’ for the people on your team: where should your retention efforts be focussed?

Netflix doesn’t operate a formal annual review process, arguing it is awkward and ritualistic. It also banished the concept of performance improvement plans because they’re dishonest. I have to agree. In many companies, I’ve observed that performance management is not a genuine way to improve performance at all. At that stage the relationship has broken down. It’s an unsubtle euphemism: for ‘You’re on the way to the exit – we’re just covering our asses from a legal perspective.’ Netflix prefers to encourage managers to monitor performance as part of their week-to-week job. Former chief talent officer Patty McCord writes: ‘We asked managers and employees to have conversations about performance as an organic part of their work. In many functions – sales, engineering, product development – it’s fairly obvious how well people are doing.’24

Innovative businesses have to tolerate a little slack: it’s essential for creativity. But that doesn’t mean they have to put up with low performance. Employees need to be talented, motivated and performing at the highest level. Manchester United is the most successful team in English football, having won more trophies than any other club. The manager doesn’t hold an annual review with players at the end of the season. He monitors a player’s performance minute-by-minute throughout a match. If the player is struggling, he’s substituted immediately. If he continues to fall off the pace required for a world-class team, he’ll be dropped from the squad and sold on. United also don’t tolerate anyone who thinks they are bigger than the club. They regularly move on brilliantly gifted players if they fail to play for the good of the team. Excellence is the currency of a creative business. A creative business aspiring to sustained excellence can’t operate like a family; it needs to operate like a world-class professional sports team.

![]()

Keep things simple: monitor how well people are doing every week; if they’re not performing, have an honest conversation to get them back on track. If this doesn’t work, arrange a win-win exit with fair support from the business. Building pointless time-consuming rituals around managing performance doesn’t improve it.

Of course time increments are different in business and sport. A 90-minute game might mean a 3-month period in business. And of course you do need to show loyalty to people; as much loyalty as you expect back. If one of your stars goes through a bad patch, you need to stick with him or her to work out if they can be a star again in your environment. Just as if your business went through a temporary dip, you would expect employees to stick around for a while before leaving. But employee loyalty and hard work are not enough. In a creative business it’s foolish to measure people on how long they’ve been an employee or how many evenings or weekends they work. Measure them on ideas and results.

![]()

Make two things clear:

- Creative businesses are fun, exciting and rewarding places to work.

- The flipside is you need to be high performers to stay on the team.

Electric conclusion

Better talent = better ideas. It’s a defining characteristic of a creative business. You need to work like a scout for a major sports club. A talent impresario has to accept it is a huge part of their job. Create a talent journey that entices, motivates, develops and retains the most talented people around – and then demand high performance.

CLEAR steps to change

Communicate

List the three people who would cause you a sleepless night if they even thought about leaving. Arrange to chat with them to find out if they feel challenged, if they are learning and developing and what their plans are in the business for the next six months.

Sit down with some key people and brainstorm the key skills, the important attitudes and most impactful outcomes for your learning programmes. In the same meeting think of the cost-free ways you can encourage 24/7 learning: end of project reviews, ideas meetings and mentoring, for example.

Learn

How do you hire currently? What is the process and criteria for finding people with the right attitude, expertise and inner motivation to break the rules’? Look at the last three people you hired – did you make the right decision? How could you do things better?

How do you seek to motivate and remunerate people? What proportion of your talent investment is in basic salary, bonus, perks – and do you have a pot of money for ‘If, then’ rewards? Can you reallocate a proportion of the ‘if, then’ rewards to be ‘now, then’ rewards to drive intrinsic motivation and creativity?

Which projects in your portfolio are the ones that everyone wants to work on? How can you ensure the right talent gets on the right projects to spark creativity? Which customer work bores everyone stiff? How can you get rid of it? What would that cost you (is it a risk worth taking)?

Energise

Redesign how your learning and development budget is being spent.

If required, redesign your reward system to spend more time and effort on encouraging intrinsic motivation.

Act

- Focus your learning programme to achieve higher levels of creativity and innovation.

- Transform your reward system based on what we now know about the balance between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

- Assess if your performance and appraisal system uses ‘tough love’ to keep your talent at the top of their game.

Warning: These actions are fundamental, so be careful about undertaking them at the same time. If you are nervous, or simply don’t have the power to do this because you are lower down in the organisation, look to cherry pick and introduce smaller, high-profile tactics that send a message about how highly you value people and their development.

Respond

After 6 months and 12 months, review the outcomes of these programmes. Are you seeing different behaviours and higher levels of learning and performance? If not, go back to the drawing board.

1 Afshar, V., 2013. 100 Tweetable Business Culture Quotes from Brilliant Executives [online]. Available at: <www.huffingtonpost.com/vala-afshar/100-tweetable-business-cu_b_3575595.html>.

2 Chin, P., CEO Langland, 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme, 6 September.

3 Langland, 2013. Andrew Spurgeon webpage available at: <http://beta.langland2013.co.uk/#/people/andrew-spurgeon-creative-director>.

4 Caves, R.E., 2000. Creative industries: contacts between art and commerce. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

5 Isaacson, W., 2012. The real leadership lessons from Steve Jobs. Harvard Business Review, April.

6 Ibid.

7 London Evening Standard, 2013. Dyson to hire 650 skilled workers. London Evening Standard, [online]. Available at: <www.standard.co.uk/business/business-news/dyson-to-hire-650-skilled-workers-8799129.html>. 5 September.

8 Quote and insight from Sutton, R.I., 2001.The weird rules of creativity. Harvard Business Review, September. p.96.

9 See the Dyson website. Available at: <www.careers.dyson.com>.

10 Gratton, L., 2007. Hot spots: why some companies buzz with energy and innovation – and others don’t. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall. p.56

11 Amabile, T.M., 1998. How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, September.

12 A debt of thanks here to Professor Teresa M. Amabile whose model this is developed from, Gordon Torr who I saw looks at the overlaps in this way and Professor John Bates who sent me his thinking on the same area.

13 Pink, D.H. 2009. Drive: the surprising truth about what motivates us. Edinburgh: Cannongate Books.

14 Ibid, p. 46.

15 Gratton, L., 2007. Hot spots: why some companies buzz with energy and innovation – and others don’t. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall. p.56.

16 Capodagli, B. and Jackson, L., 2009. Innovate the Pixar way: business lessons from the world’s most creative corporate playground. McGraw-Hill Professional. p.54.

17 Gratton, L., 2007. Hot spots: why some companies buzz with energy and innovation – and others don’t. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall. p.56.

18 Ibarra, H. and Hansen, M.T., 2011. Are you a collaborative leader? Harvard Business Review, July. p.73.

19 Figures from Hay Group. The employee turnover threat to your organization. The Hay Group [online]. Available at: <http://web.haygroup.com/0-the-employee-turnover-threat-to-your-organization?gclid=CLaymrqGzboCFQjKtAodLnwA8Q>.

20 In 2011 the Corporate Executive Board’s quarterly study of 20,000 employees over the second half of 2011 took a look at the biggest driver of employee retention work through attraction, hiring, retention, development.

21 Casserly, M., 2011. What employees want more than a raise in 2012. Forbes 2011 [online]. Available at: <www.forbes.com/sites/meghancasserly/2011/12/15/what-employees-want-more-than-a-raise-in-2012/>.

22 Figures from Hay Group. The employee turnover threat to your organization. The Hay Group [online]. Available at: <http://web.haygroup.com/0-the-employee-turnover-threat-to-your-organization?gclid=CLaymrqGzboCFQjKtAodLnwA8Q>.

23 McCord, P., 2014. How Netflix reinvented HR. Harvard Business Review, January–February.

24 Ibid.