Habit 9

Demolish idea barriers

How to dynamite the walls that block creativity

You’ll learn:

“The barriers are not erected which can say to aspiring talents and industry, ‘Thus far and no farther.’”

Ludwig van Beethoven, composer

Channel 4 is an advertiser-funded broadcaster founded by British government charter. The charter decrees Channel 4 has to deliver innovative content to the UK. This unique legal status means external collaboration is not just a good idea – it’s mandatory. Be creative, or break the law. In fact, Channel 4 doesn’t make any programmes. The business commissions all its creative content from a pool of around 500 external suppliers ranging from one-man band start-ups to global TV producers.1

To ensure geographic diversity, Channel 4 is required to source about a third of its programmes from outside London and from the smaller nations of the UK – Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. On top of these legal rules, voluntary management policies ensure restless change: job descriptions for commissioners make it clear they have to work with a certain number of new businesses every year. Being a ‘publisher-broadcaster’ has proved to be an advantage. Channel 4 can spot promising ideas, wherever they come from. For example, the reality TV show Big Brother was picked up from a Dutch company, Endemol, and developed by Channel 4 into a money-spinning UK hit. ‘Working with different suppliers is a big part of our success,’ explains director of creative diversity Stuart Cosgrove in his gravelly Scottish accent. ‘It means we can navigate change more effectively. We haven’t built up big, inflexible in-house production functions. If we want to change the nature of what we do, we don’t have a department we have to make redundant. We just shift the radar of our creative commissioning.’

Channel 4 knows it must be careful not to become too reactive and dependent on others for the creative spark. ‘As well as being a strength, there is an inherent danger in the outsourcing model,’ Cosgrove explains. ‘We know we must avoid waiting for creativity to drop into our in-box.’ To proactively set the agenda for suppliers, Channel 4 executives invest two hours every week in a freewheeling discussion of the next big thing. The output of this get-together provides a tight brief for external producers. ‘In higher education you’d probably call it a seminar!’ laughs Cosgrove. ‘Over breakfast every week we have a wide-ranging chat. Today it was about the topic of the pros and cons of London as a Super City. We don’t necessarily get to a finished idea. We’re looking to see tram lines of change. Sometimes the meeting leads to a dead end. But sometimes it leads to a commission, some new research, or the pursuit of a new avenue.’

Cosgrove argues the core of the channel’s creative success is derived from a ‘culture of curiosity’. It’s propagated from the moment a new person is inducted. Staff feedback shows employees are very proud of the business’ purpose. Cosgrove added: ‘If you are not engaged with the core innovative purpose of this organisation, it’s highly unlikely you will survive here very long. But we don’t insist people sign up like it’s some kind of religion; that might squash their curiosity or lead to a fear of failure.’ To ensure people ‘fit in’ the business takes great pains to find and hire focused, ambitious talent who have been innovative before coming into Channel 4. ‘We have to ensure the people that are in creative dialogue with the best suppliers, are themselves the best in the business,’ argues Cosgrove.

Cosgrove’s creative diversity team is an investment to ensure Channel 4 takes risks. He explains: ‘I have two metaphors for what we do. We are like the music industry A&R [artists and repertoire] men, looking for the next hit band. But we are also Sherpas: we understand how to navigate the “Channel 4 Mountain”. So, we help external suppliers to work the system, get quality meetings and improve their own creativity.’ The team also distributes a £2 million seed fund each year to outside businesses in small chunks of £5–10,000. The Alpha Fund is earmarked for developing promising new ideas. Cosgrove estimates only 20 per cent of the shows funded by Alpha money get commissioned; and under 10 per cent then go on to be hits. ‘But you can dine out on those for years,’ he laughs.2

![]()

Organise your own blue skies meeting about the ‘Next Big Thing’. No agenda. Invite people to come along with customer stories, snippets from magazines, YouTube videos and new ideas – anything to give the discussion a creative spark.

Clear out the cobwebs

When businesses start up, they are always creative. But, as they grow up, they seem to lose that energetic, entrepreneurial spirit. What happens? Dame Gail Rebuck, chairman of the UK arm of Penguin Random House, says she is always shocked by the latticework of bureaucracy that grows over time. ‘You have to constantly go back into the attic and clear out the cobwebs,’ she said. ‘Rules put in place to solve a particular problem linger on long after the person who put it in has forgotten about it because the problem’s moved on. Old initiatives that were important at the time then clog up the system.’3

Businesses walk through stable periods of evolution until it becomes obvious the way it is organised doesn’t match the changed world it now inhabits. It then hits a crisis.4 When you’ve worked with lots of businesses, as I have, you realise these crises are actually predictable, necessary and valuable. A better name for them is turning points: they present an opportunity for the business to grow up. How often these crises occur depends on the rate of business growth and industry change. But the managerial response to them can erect bureaucratic barriers that stifle creativity later on. Here are three common crises – and the barriers erected as a result – that I’ve observed over the years:

- Leadership Crisis: An entrepreneurial business is growing fast through creativity and good ideas. But one day they realise chaotic day-to-day creativity is not enough. The management team decides: ‘We need a clear direction!’ Professional management and planning is introduced. But, if it’s not handled well, there is trouble in store. Result: too much directive management stifles initiative.

- Middle Management Crisis: The business gets even bigger. It becomes clear: ‘We need more mid-level managers!’ New structures are introduced, based on delegation. But, this is done without sufficient people development. Result: middle managers don’t understand the values and behaviour required to run a creative business.

- Control Crisis: The business expands further – perhaps branching out overseas. Middle management can’t cope with the level of complexity and demands on its time. The board decides: ‘We’re out of control!’ The response is to create separate departments, as well as support functions like finance, HR and marketing. But, the new system is not supported by improved communication. Result: the business is too bureaucratic and fails to promote sufficient collaboration.

![]()

Think about the growth crises your business has gone through. Identify any of the managerial responses they provoked that are now crushing creativity – and get rid of them.

Of course, all businesses need to professionalise and go through these rights of passage in one way or another. Bureaucracy is not a dirty word – it can be necessary and sensible. If businesses can’t change, they end up in crisis mode perpetually. As a business grows, there will be a tendency to respond to predictable crises by building hierarchy, specialised roles, permanent departments and a more formal structure. If you are not careful, people stop communicating. You build internal and external barriers, which kill collaboration. Like humans, companies tend to base their habits on previous events and experiences. This leads to organisations fully equipped to deal with the past; but less and less equipped to deal with the future.

Superficially, it seems like there are three unattractive options for growth:5

- Stay creative by staying small.

- Try to avoid rules as you grow (which leads to chaos).

- Develop complex rules and processes as you grow to drive efficient execution but cripple creativity and the ability to respond to change as a result.

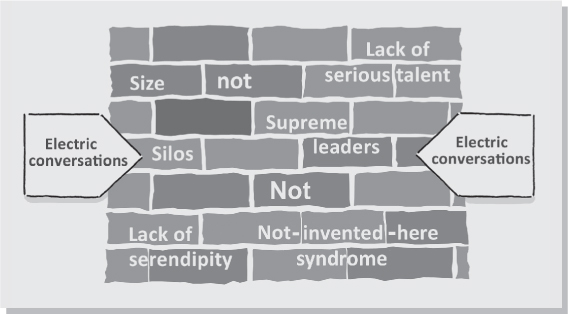

Of course, the best option is to grow the business in a way that actively encourages collaboration: and become more creative as you get bigger. That’s what this habit (and the next) is all about. It’s your job to become aware of barriers and occasionally dynamite these walls to preserve and nurture the rampant creativity of the company’s younger, wilder days. There are six barriers you need to be particularly aware of: size, silos, lack of serendipity, lack of serious talent, supreme leaders and not-invented-here syndrome, as shown in Figure 9.1.

figure 9.1 Idea barriers

1 Size

The entrepreneurs I work with are always dreading the moment when their company loses its mojo. They fear at a certain size the business will become bureaucratic, leaden and uncreative. Meanwhile, the executives I work with in bigger, global businesses often bemoan the red tape that encircles them. Intuitively we know it’s a little easier to communicate, collaborate and be creative in a smaller business. After all, if you’re all in one room, it’s less effort to share information and nimbly relocate people from one project to another. Jonah Lehrer, in his research on how imagination works in business, describes how large companies lose the plot: ‘They keep people from relaxing and having insights. They stifle conversations, discourage dissent, and suffocate social networks. Rather than maximising employee creativity, they become obsessed with minor inefficiencies.’6 A remarkable survey of more than 8,500 publicly traded companies in the USA showed, as the number of employees grew, profit per employee shrank.7 This shouldn’t happen. It defies the basic economic logic of economies of scale (as you get bigger you can do things more cheaply). For creativity, size clearly matters.

But big businesses don’t necessarily have to be uncreative. They have a lot going for them: strong client relationships, stable finances and the ability to take the kind of long-term view required for leading a creative culture. So, why do they so often become unimaginative? The researchers in the study above came to the conclusion the businesses in question failed to reap the expected benefits of size because of their inability to collaborate.

A way to encourage collaboration – and to fight the creeping death of turning into a ‘big, stupid’ business – is to stay small, even as you get bigger. A study spanning Europe, Japan and the USA found many innovative companies limit the headcount of their operating units to fewer than 400 employees. W.L. Gore & Associates is one of them. Gore is a technology business specialising in product innovation: from medical devices that treat aneurysms to high-performance GORE-TEX® fabrics. Gore has grown from a garage start-up into a 9,000-person company with sales of $3.2 billion. Management has tried to keep collaborative teamwork alive by erecting a new building in the Delaware countryside every time a team exceeds 150 people.

You can see this ‘small-is-better’ attitude in marketing services giants like WPP, Publicis and Omnicom. These are global service businesses that have become dominant by voraciously buying smaller agencies. But they don’t rebrand new acquisitions to become part of a corporate whole. Instead, they encourage them to retain their identity. WPP head office plays an across-the-group role in property management, procurement, IT and knowledge sharing – but that’s about it. WPP has an army of 170,000 employees, but these people don’t identify with WPP. They identify with the hundreds of differently branded agencies that employ them.8

The ‘right’ group size for successful collaboration might be programmed into us from an earlier age. Evolutionary experts argue a human tribe of around 150 is bred into our DNA because this is how many people banded together in pre-historic clans.9 So, occasionally, you may need to preserve barriers around smaller collaborative groups within a larger business. But, even if a business chooses to keep operating units at a certain headcount there still needs to be collaboration and knowledge sharing between these units. To ensure that happens you need to avoid silos.

2 Silos

Size is not the problem that stops electric conversations: it is attitude. A common complaint I hear when I talk to leaders is: ‘We’ve developed a silo-mentality’:

- In 2010, a former Microsoft executive revealed the giant software company developed a viable tablet computer years before Apple scored a commercial smash hit with its own model. The idea had been killed by feuding Microsoft divisions and the promising prototype had been allowed to gather dust in some gloomy basement.10

- Over a convivial pasta lunch in South Kensington, managing director of Lion TV Nick Catliff told me his ideas team had a name for broadcasters that had destroyed their own creative culture through silos: ‘Dead Stars: when it becomes corporate, fear-driven, too marketing focused – they die. There’s no inspiration. When you talk to people in Dead Stars, you know what they talk about? They don’t talk about ideas – they talk about each other. They talk about who has power and who doesn’t. They’re terrified of passing a new idea up the chain in case their boss doesn’t like it.’

![]()

Review incentives – are they encouraging people to work exclusively within their own group?

Silos range from different teams hoarding information to the corrosive mistrust sown by politicking and turf wars. You don’t need to be big to build silos. I’ve seen silos in 20-person businesses all working in the same room. When organisational barriers go up it destroys trust, fosters complacency and leads to missed opportunities.

![]()

Show commitment to silo destruction by explaining the importance of collaboration. Follow up with practical measures such as networking and recruiting people from outside the silo.

3 Lack of serendipity

The physical environment can prevent serendipitous electric conversations that create the spark of ideas. Despite being a guru of the digital world, Steve Jobs knew the value of face-to-face meetings. He argued: ‘There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email. That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say “Wow!”, and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.’

As a founder of Pixar he designed the HQ to make sure people bump into each other.11 ‘If you don’t do that, you’ll lose a lot of innovation and the magic that’s sparked by serendipity. So we designed the building to make people get out of their office and mingle in the central atrium with people they may not otherwise see,’ he said. At Pixar you have to visit the atrium as it acts as a hub for the front doors, the main stairs, all of the corridors, the café and mailboxes. Even the conference rooms have windows that look out onto the atrium. And, when you’ve finished viewing a film in the 600-seat theatre, where does the exit take you? You guessed it: the atrium. Pixar chief operating officer John Lasseter, the man behind films like Toy Story, Cars and A Bug’s Life, said: ‘Steve’s theory worked from day one. I kept running into people I hadn’t seen for months. I’ve never seen a building that promoted collaboration and creativity as well as this one.’ Other businesses have followed suit:

- In 2012, the London-based advertising agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BBH) took the decision to redesign its Central London office to make it a more playful, collaborative creative space. Executive creative director Nick Gill opened up the agency’s central atrium to encourage the collision of ideas and people. It’s an exciting place to visit with a central free coffee stall amid sculptures of BBH’s iconic sheep dotted around the light pine floors. Creative hubs are located in positions staff are bound to walk past. These are essentially open-ended meeting rooms without walls to discuss projects and ideas. Gill said: ‘It’s true that your environment affects how you feel and how you work. Well, it has never felt better coming to work as it does now.’12

- When BMW built its factory in Leipzig in 2005 it wanted to encourage collisions. Slightly ironic for a car maker. The facility has an open-plan layout to encourage workers to strike up spontaneous conversations and share ideas across the business.13

As virtual working makes tools like Skype, online networking and conferencing more sophisticated, the need for face-to-face interaction to provoke creativity may lessen slightly. But only slightly. There will always be a need for some collaboration to take place in the same room, face-to-face.

![]()

Most offices don’t have an atrium. Create ‘serendipitous’ opportunities for staff to catch up and exchange ideas through informal off-the-cuff outings and meetings.

4 Lack of serious talent

Many companies curtail freedom as they grow, to avoid errors. It’s hard to find anybody who would argue against reducing errors. But shackling employees and increasing rules, complexity and red tape has the unfortunate side effect of driving the most creative people out of the business – and into the arms of a more enlightened competitor. This is bearable in the short-term because fewer mistakes are made and the business is productive. However, the true cost of a brain drain reveals itself when your market changes, due to a new technology or competitive product. At this point, there is nobody left in the business with a sufficiently innovative mindset to help you respond and survive. Game over.

Netflix has a simple move to avoid disaster. Management at the US on-demand internet media business avoids ‘rule creep’ and ‘barnacles’ – its word for unnecessary products – like the plague. It argues if you focus your products and services, all you need to do is ‘increase talent density faster than complexity grows’. It’s a great formula for a creative business: a simple and compelling USP to retain a higher proportion of talented people in the workforce than competitors. Chief talent director Patty McCord writes: ‘Our model is to increase employee freedom as we grow, rather than limit it, to continue to attract and nourish innovative people, so we have a better chance of long-term success.’14

5 Supreme leaders

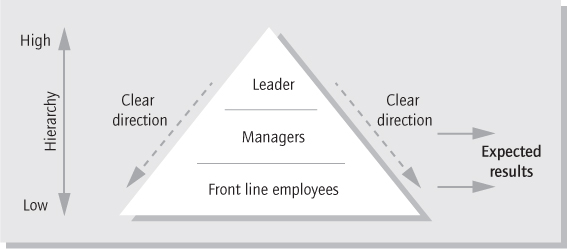

Who’s got power, and who hasn’t, infuses conversations and interactions between humans. The normal leadership and management model looks like this: big bosses tell middle-size bosses what to do and they then tell everyone else (see Figure 9.2).

figure 9.2 The normal management model

For creative leaders the world is upside down. As much as possible, they flatten hierarchy to allow ideas to be judged objectively. They see the world in a different way from ‘normal’ leaders:

- Attitude: Being as available as is practical for conversations with employees – and effectively communicating the other way.

- Structure: Examining the structure of teams and departments to ensure there aren’t unnecessary ‘layers’ of intervening managers between the most senior person and the most junior, which block communication and slow decision making.

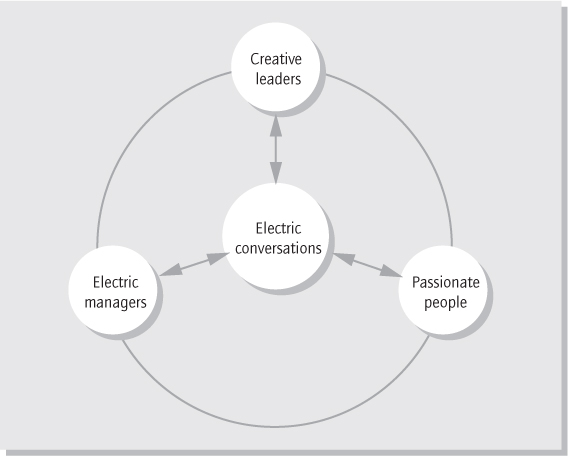

The oil that makes the engine run is a constant, creative and challenging electric conversation; far more likely to happen in a non-hierarchical organisation. The relationships look more like those shown in Figure 9.3.

figure 9.3 Electric conversations management model

Here ‘the work’ – creativity, innovation and results – is the dominant force in the business. Everyone from leaders to freelancers is focused on ideas – rather than their place in the pecking order. Of course, creative businesses still have organisation charts. There is always a need for focus, as well as freedom. But the fundamental hierarchical assumption that the ‘boss knows best’ is challenged by the values of a creative business.

Liz Darran, director of brand and creative at Sky, is a great believer in removing barriers to encourage what she calls ‘casual conversations’. She said: ‘Encouraging creativity is about shattering hierarchy, pulling out unnecessary processes and reducing the management of complexity. You need to find the simplest possible ways for ideas to come to fruition: the least number of people in the chain. It’s about building a more communicative group.’ Like many other creative leaders I’ve worked with, Darran accepts collaboration is not always easy: ‘We need to have some heat and fire in the discussions. It can’t be about everyone just agreeing. You need some conflict as well as some agreement – collaboration can be both of those things. There can be friction; it doesn’t need to be entirely positive.’15

![]()

Be humble and try to keep a check on your ego: ‘forget’ your hierarchical position as often as you can.

5 Not-invented-here syndrome

Creative businesses avoid not-invented-here syndrome. They sidestep the self-deluded self image that arises after a modicum of success, ‘nobody’s as good as we are’. Sometimes the barriers that need to be demolished are between you and the rest of the world. US academic Keith Sawyer has studied collaboration in jazz bands, improvised comedy troupes, as well as commercial teams. He argues businesses need to: ‘lead collaborative webs extending beyond their company’s boundaries.’ A top designer once winked at me and said: ‘We borrow with pride!’ He was referring to a willingness to listen equally to freelancers, suppliers, customers and competitors. Anyone with a good idea is worth listening to.

![]()

Never stop an electric conversation at the border and ask to see its passport. Collaborate with the best you can find. No company has a monopoly on good ideas.

Collaborating with customers

Creative businesses spark electric conversations with customers while clearly communicating the opportunities and risks of innovation. Jeremy Shaw, chief operating officer of the London agency Kitcatt Nohr Digitas said: ‘You have to encourage clients to trust you, and to be brave. You have to have a proper relationship with them so they can challenge what you are doing – but you can also push back. One client once said to me “Your job is to make us uncomfortable’16. Forming a non-hierarchical relationship with people who are signing the cheques requires a degree of honesty and self-confidence. Wally Olins, who co-founded the branding agency Wolf Olins said: ‘Creative businesses need to work with clients on what they truly need. The clients and consultants need to be honest with each other. They need to co-create the brief.’17

Customers have always contributed to new product development. During the First World War the shortage of cotton meant army surgeons had to resort to using an absorbent substance made from wood pulp called Cellucotton. At the end of the conflict, the manufacturer Kimberly-Clark was left with a mountain of the material. But then something unexpected happened. Kimberly-Clark found that men were using Cellucotton to blow their nose. It took a while for the business to catch on, but eventually they marketed the product as a handkerchief and Kleenex blew us all away.

The digital revolution means collaboration with customers is here to stay. ‘Lead users’ are gold dust and companies all over the world are making the most of them:

- Lego has developed its products far beyond its simple starting point, with the aid of willing (and fairly obsessive!) customers who will play, and experiment, for free.

- Some games publishers allow ‘modding’ in which innovative gamers programme new features to products after they have been released.

- Amazon and eBay have based their business model on sharing a percentage of sales with an eco-system of customers and secondary sellers.

- In the hi-tech world of scientific instruments, customers are the source of over 80 per cent of all innovation.18

- Software business SAS has always invited customers to give feedback on their products through global forums and conferences.

- After years of holding internal ‘ideas jams’ with its employees, in 2006 IBM had the bright idea to invite in its customers, too.

![]()

Collaborate with your customers. Smart ways to get them involved with product development include focus groups, mini-conferences and online feedback.

Learning from competitors

Some businesses embark on a learning journey to embrace a new way of perceiving the competitive landscape. Facing an unprecedented wave of digital change in all of its global TV, music and book publishing concerns, the German media giant Bertelsmann knew it needed to radically change attitudes inside the business. In November 2013, it dispatched 180 of its most senior executives to ‘Digital Book Camps’ to learn about the disruptive trends – and the threats and opportunities – they presented. This was a significant investment; these were key decision-makers from the European TV and radio business RTL Group, global publisher Penguin Random House, Gruner + Jahr in magazines and BMG music.

But this was just the start. After achieving a consistent level of digital knowledge within the group, Bertelsmann asked them to pack their suitcases again and leave for what’s recognised as the most innovative place on Earth: Silicon Valley. The leaders were treated to a week of inspirational speakers, experiences and company visits. This was a huge investment of time and money, even for a company the size of Bertelsmann, but many felt it was worth it. ‘It was a life-transforming experience. I understood the trends before that, but I wasn’t sure I “got it”. After this I got it! It works because, if you put a creative person in a new environment, they are hardwired to learn and to change,’ said Dame Gail Rebuck, UK chairman of Penguin Random House, one of the executives on the trip.

You don’t need to fly your people to Silicon Valley. The creative director of a digital agency in London I know bought membership of Tate Modern for his creative team. He insisted they go to think about tough projects in the members’ room, which has a stunning view of St Paul’s across the Thames – as well as six floors of modern art a few minutes’ away. ‘It’s a wonderful way to let creatives liberate their minds,’ he explained.19

![]()

Get your people out of the office to learn – especially when they’re stuck on a big project. Make sure they visit places and people which will challenge their preconceptions.

Open innovation

Open innovation is the idea businesses, even big ones, need to look outside if they are going to stay relevant in today’s fast-changing world. In 2003, consulting firm Accenture analysed where ideas came from in 40 global companies across 5 industries. The result was striking: 45 per cent of innovation came from outside the business. This trend has spawned a mini-industry of online ‘idea marketplaces’. These forums match experts from a variety of fields with problems that need to be solved:

- Created by the consumer products giant Procter & Gamble, Nine Sigma links scientists to knotty technical challenges.

- Founded by the global pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly, InnoCentive pays researchers financial rewards for useful solutions to difficult problems.

Nestlé invests heavily in new idea generation: spending nearly 2 per cent of revenue every year on research and development. This adds up when sales are worth €80 billion. For the last two decades, new product development has been the core of Nestlé’s vision: being the world leader in ‘nutrition, health and wellness’. The company employs 5,000 people in 24 internal R&D centres scattered across the world.20 You might think this was enough. You’d be wrong. Nestlé taps into the expertise of more than a million external researchers worldwide: university and government scientists, venture capitalists and suppliers. Paul Bulcke, Nestlé’s chief executive, commented: ‘The biggest danger we face is that we become complacent.’21

Occasionally, this massive investment pays off. Take Nespresso: ‘coffee-shop-quality coffee at home’. You buy a system. First, a mini version of the Starbucks-style machine, and then, each month you purchase online supplies of vacuum-packed fresh coffee capsules. It’s an invention that powered the early-morning writing of this book. More importantly, it’s now a €1 billion brand growing at over 40 per cent per annum.22 The global superpower in open innovation is Procter & Gamble (P&G). P&G replaced an old-fashioned internal innovation mentality with an outward focus it calls ‘connect and develop’. The results are impressive. Over a third of P&G’s products are now invented in partnership with someone else. A good example is the Swiffer Duster. At the time, P&G had more PhDs on their staff than the combined university faculties of MIT, UC-Berkley and Harvard. Yet they were still struggling to come up with a new way to innovate upon the humble mop. They decided to improve their chances by working with Continuum, a specialist innovation consultancy. P&G’s approach had been to tinker with chemical molecules to make a stronger cleaning fluid. Continuum tried something else: spending time with customers. A lot of time. They shot hundreds of hours of video footage in the process. One extract showed an elderly woman improvising: using a damp piece of kitchen roll on the end of a mop to pick up spilt coffee granules and then throwing the kitchen roll away. This lead to P&G’s ‘aha!’ moment: a fabric throwaway element at the end of the mop. The Swiffer was born. The product has cleaned up (apologies), generating more than $500 million dollars in sales.23

![]()

Refuse to be insular and inward-looking – look outside for ideas. Partner with a university department that studies your professional discipline, find an online business forum that allows you to post and share interesting questions – or collaborate with another firm in a related field.

The CEO of a global media production business turned to me on the first morning of a major leadership development programme and whispered: ‘I want this to be a particle accelerator for ideas’. We had brought together a group of executives who previously had little contact with each other. The CEO hoped the relaxed discussions and networking of a leadership programme would bring her top people together, so their ideas could collide like atoms at the speed of light. Luckily it worked just as she hoped.

Creative business people tend to be skilled and relentless networkers. Not just because they enjoy free food and drink. It’s how ideas happen. Online networking helps, but a creative business thrives on the sparks created by face-to-face meetings. A defining attribute of a creative business is the importance of relationships: you need to meet with someone to get the human dynamic just right. In the advertising world ‘chemistry meetings’ are par for the course. It’s in these encounters that electric conversations happen, half-formed ideas collide, unplanned aha! insights occur.24

There is growing scientific evidence proving networking grows your bottom line. Sociologists found that human beings are remarkably similar in the number of strong relationships they have in their lives. These ‘strong ties’ normally number between four and seven close friends. These are the people you see on a regular basis. The people you call if your house is burgled. But when it comes to ‘weak ties’ – people you know, but not that well – there is no such uniformity. Some of us have a handful; others have literally thousands. Take Yossi Vardi, the legendary Israeli entrepreneur and dotcom fixer. He puts people, ideas and investment together and has been an instrumental figure in the remarkable blossoming of the Israeli technology sector over the last two decades. Google co-founder Sergey Brin once said: ‘If there is an internet bubble in Israel, then Vardi is the bubble.’ Vardi is a world-class networker with a vast number of weak ties.

Science backs the common sense of Vardi’s endless networking. For example, entrepreneurs that meet with an almost random kaleidoscope of people are three times more likely to file a patent than their colleagues with a small network. The logic is simple: your close friends have a similar set of ideas and knowledge to you: ‘they know what you know’. Weak ties are far more likely to possess a new idea, left field opinion, an interesting fact that can spark creativity.25

But you have to work at it. Human beings are hardwired to stick to their own. Sociologists call it the ‘self-similarity principle’. That’s why, when you’re at a party, you end up gossiping with the person who shared a school, university or career path with you. You’ll have a good time discussing common knowledge, but the conversation probably won’t help you have a radical new idea.

![]()

Connect yourself – and your staff – to the outside world. Encourage them to join professional bodies, write blogs, speak at conferences and network online. Somewhere out there is a creative spark waiting to happen.

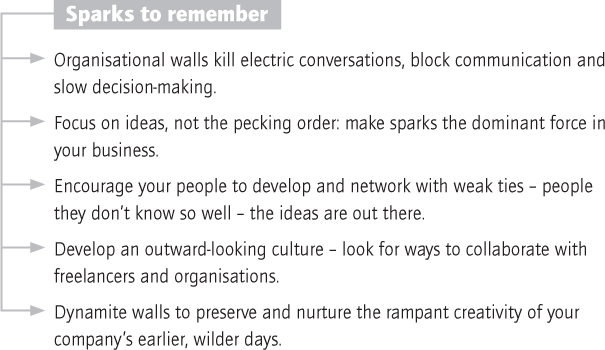

Lightning conclusion

All businesses need to grow up. But you need to be careful what barriers are being built as it happens. Be aware of which boundaries are useful, and which are getting in the way. Don’t be afraid to take a hammer to the walls that stifle electric conversations.

To dismantle your walls, and break down silos, design your environment to make people mingle, increase talent density faster than business complexity and collaborate freely with customers, competitors and partners. If you manage for a non-hierarchical, open, idea focus, you can become more – not less – creative as you grow.

CLEAR steps to change

Communicate

Send a signal about your thoughts on supreme leadership: gather a group of your most junior people and ask: ‘What do you think we could do better around here?’

Learn

Look at your rules, policies, processes and business structure and ask yourself: ‘Which of our walls are blocking the development of new ideas?’

Energise

Make a list of the top three walls that are definitely just ‘cobwebs’ from a previous growth crisis.

Act

Dismantle one of these walls; check to see this worked and improved creativity before moving to the next. Remember: this is not just about efficiency and productivity – it’s about increasing electric conversations.

Also:

- Is there a way you could create an ‘ideas space’ – an opportunity to ‘bump into each other’? It doesn’t need to be expensive. At Major Players, an innovative London-based recruitment business I worked with, one of the teams organised British high tea one afternoon per week on a revolving basis. Tea, cake and a chance to chat without an agenda. The main thing is to use your imagination to make these opportunities feel creative, informal and fun.

- We all know about the power of networking in business. But when was the last time you organised a networking event for your own people involving key clients, suppliers and people outside your current network? I’m not talking about the run of the mill bonding and booze exercises, which generally produce more hangovers than new ideas, but something that genuinely will challenge and create sparks.

Respond

After you have taken the actions above are there other routes to circulate knowledge and ideas in your team? If so, look to dismantle even more barriers.

1 The Producers Alliance for Cinema and Television (PACT) is the trade association representing the commercial interests of UK independent television, film, digital, children’s and animation media companies. PACT has a membership of around 450; Channel 4’s director of creative diversity, Stuart Cosgrove, said that in 2012–13 Channel 4 worked with 430 suppliers.

2 Cosgrove, S., 2013. Stuart Cosgrove, Channel 4’s director of diversity, interviewed by Greg Orme on 1 October.

3 Rebuck, G., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme on 7 November.

4 Greiner, L.E., 1972. Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, vol. 50(4).

5 Inspired by Netflix, 2009. Reference guide on our freedom and responsibility culture.

6 Lehrer, J., 2012. Imagine: how creativity works. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p.209.

7 Ibid.

8 WPP. WPP at a glance. Available at: <www.wpp.com/wpp/about/wppataglance/>.

9 Sawyer, K., 2007. Group genius: the creative power of collaboration. New York, NY: Basic Books. p.154.

10 In an interview with The New York Times.

11 Isaacson, W., 2012. The real leadership lessons from Steve Jobs. Harvard Business Review, April.

12 Sheep are important to BBH, as it sees itself as a black sheep standing out from a herd of white ones.

13 Sawyer, K., 2007. Group genius: the creative power of collaboration. New York, NY: Basic Books. p.165.

14 Netflix, 2009. Reference guide on our freedom and responsibility culture.

15 Darran, L., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme at Sky on 25 September.

16 Shaw, J., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme at Digitas Kitcatt Nohr, April 16.

17 Olins, W., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme at Saffron HQ in London on May 22.

18 von Hippel, E.A., 1976. The dominant role of users in the scientific instrument innovation process. Research Policy, July, 5, no. 3.

19 Kitcatt, P., 2013. Interviewed by Greg Orme at Digitas Kitcatt Nohr on October 1.

20 Traitler, H. and Sam Saguy, I., 2009. Creating successful innovation partnerships. See: <www.ift.org>.

21 Bell, D.E. and Shellman, M., 2009. Nestlé in 2008. Harvard Business School.

22 Bell, D.E. and Shellman, M., 2009. Nestlé in 2008. Harvard Business School.

23 Lehrer, J., 2012. Imagine: how creativity works. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. xv.

24 Goffin, K. and Koners, U., 2011. Tacit knowledge, lessons learnt, and new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 28, pp. 300–318.

25 Lehrer, J., 2012. Imagine: how creativity works. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p.205.