1

Strategic Purpose

I have a dream ...

Martin Luther King

The most widely used Strategy Tool in the world is the SWOT analysis, which stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats – and it has been so for 60 years. And yet many using it are disappointed with their results.

Why?

The problem is often that the SWOT analysis isn’t aimed at anything. It only works if you know where you are trying to go. As Lewis Carroll’s Alice asks the Cheshire Cat: “Would you please tell me which way to go from here?” To which the Cat replies: “That depends on where you want to get to.” Opportunities only have meaning if you know where you are going. Weaknesses are only strategic weaknesses if they make it difficult to achieve what you are striving for. Defining elements of SWOT without articulating your purpose is a pointless exercise. So without first articulating what your aim is, what purpose you are trying to achieve, or what winning looks like, a SWOT analysis can be time consuming, frustrating and ultimately unfruitful.

Knowing where to go is the point of Martin Luther King Jnr’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which painted an aspirational picture of the aim of the American Civil Rights movement: a picture of a country living up to the creed of its founders (that all humans are created equal) and a nation enacting its better nature. It greatly helped his followers and his organisation, and inspired others around the world concentrating on civil rights to stay focused, see the big picture when times were tough and develop strategies that would lead toward the achievement of this aim.

King’s example of the importance of clarity of strategic purpose is supported by other inspirational characters such as Yogi Berra who said, in his distinctive style, “You’ve got to be careful if you don’t know where you’re going, because you might not get there”, and Abraham Lincoln: “If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it” – an excellent synopsis of an effective strategy process.

All of these quotes indicate that any really effective strategy development process starts with a dream, a purpose. Without this, any discussion about what strategies should be followed can lead, as it did for Alice, to a lot of energy being expended for the sake of going around in circles. Indeed a loss of purpose can also lead to organisational decline and failure – a situation LEGO found itself in, after years of strong growth, with huge losses in 2004.

In this, our first chapter, we discuss what an organisation’s strategic purpose might be, the vehicles (such as vision or mission statements, corporate philosophies etc.) that organisations can use to articulate what winning looks like for them in this sense, the key stakeholders and advisors who can influence and determine an organisation’s purpose and the constraints upon their power, and how such stakeholder interests can best be managed.

It’s Not Just About the Money

While the majority of strategy research has been focused upon determining the key variables that lead to positive financial outcomes in the short term (with limited success, it has to be said), organisations in practice are more complex with a plurality of purposes. Organisations may have loftier aims than just short-term performance, aiming to help a community, improve the environment and advance sustainability, increase human knowledge and/or create new ideas and products. And indeed, focusing exclusively on short-term financial goals can be detrimental to the creation of long-term value in these other respects.

For example, world famous ice-cream maker Ben and Jerry’s website says, “If you’ve ever enjoyed our Chocolate Fudge Brownie or Half-Baked™ ice cream flavours, then you’ve already had a taste of Greyston’s greatness. We first tried their incredible brownies back in the late 1980s, and we’ve been ordering tons of them ever since.” Best known for producing the brownies in the famous Ben and Jerry’s ice creams, the Greyston Bakery is a New York-based for-profit business that has been running profitably for over 30 years.

What is the purpose of the Greyston Bakery business?

In our experience of teaching business students around the world over the past 30 years, the majority will have responded that it is “to maximise profit for shareholders” – a classic response derived from the famous economist Milton Friedman’s work at the Chicago School of Economics in the 1970s. Some in the class may look slightly perturbed and only a few may disagree, although they would be right to question the assumption. But we do sense that things are starting to change, and we would like to advance a broader perspective as exemplified by Greyston Bakery.

The Greyston Bakery is located in the poor neighbourhood of Yonkers, New York, where there is a need to create jobs for “hard to employ” people – the homeless, those with poor employment histories, prison records and past substance-abuse problems. Radically, they use an “open hiring” practice that continues today, in which anybody who applies for a job has an opportunity to work, on a first-come, first-hired basis. According to CEO Julius Walls, “The company provides opportunities and resources to its employees so they can be successful not only in the workplace but in their personal lives. We don’t hire people to bake brownies; we bake brownies to hire people.” Success is when an employee moves on to a new job using their new skills. With expansion, the bakery has realised that providing jobs to the community is not enough and so now provides permanent housing for homeless people, after-school care, health services and community-run gardens. As CEO Steven Brown said: “Really, we were a benefit corporation long before the term was coined. You’re in business for a much larger community that has a stake in what you are doing. Creating value and opportunity is the path out of distress for communities.”

The Greyston Bakery example shows that organisations can have purposes broader than just making a profit for shareholders and that to assess any organisation it is important at the outset to establish what its purpose is.

Vehicles for Strategic Purpose

The strategic purpose of an organisation matters. Indeed when the toy maker LEGO was facing a crisis after years of expansion and poor financial results, the CEO realised that the company had lost its direction. The key to turning around LEGO was to rediscover what its purpose was. If the purpose of an organisation is not clear to stakeholders, whether inside or outside, then they will form their own views – and these may cause confusion and may even lead to negative interpretations. In stock market terms this can lead to share prices being downgraded and for employees and other stakeholders this can have a demotivating effect. However, a clearly defined and expressed purpose can be highly motivating to all stakeholders. Purpose can be captured in an organisation’s vision, mission, core values and objectives.

Vision

A vision articulates a view of what the organisation wants to achieve or the future it is aiming for. Vision is “big picture” thinking that helps people feel what the organisation is trying to do. It tends to be enduring and often is short. For instance, the Ford Motor Company’s vision when established by Henry Ford was “To make the automobile accessible to every American” and Starbucks successfully drove its strategy with the vision: “2000 stores by the year 2000”.

Good visions generally adhere to five principles. They are:

- Brief (not long-winded “hero sandwiches of good intentions”, as Peter Drucker said)

- True to the particular organisation’s identity and focus

- Easily understandable to all employees

- Inspirational, and

- Verifiable so that progress and ultimately success can be determined.

Mission

Mission statements should also adhere to the tenets above but there is a subtle but important difference between a mission and a vision. The root of the word vision is the Latin vide (to see) whereas mission’s root means “to send”. Consequently, a mission is not so much a goal or a picture of where you want to get to in the future, but rather a philosophy, or way of moving towards the vision in the present. Organisations can therefore have both a vision and a mission. For example, LEGO’s vision is “Inventing the future of play”, while its mission is to “Inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow”. Other classic missions include: Walt Disney’s “To make people happy” and Tesco’s “Every little helps”.

Core values

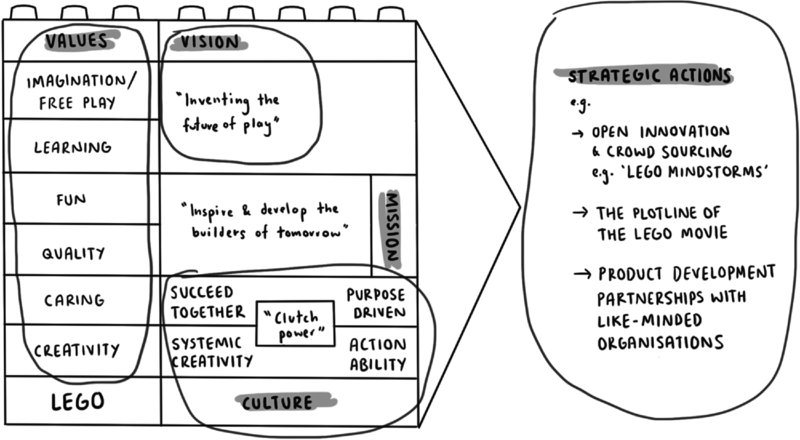

Organisations often list a number of core values, beliefs or principles that guide their decision-making. Previously derided for being bland and generic, organisations are now striving to make these more specific, more interesting and hence more useful from the point of view of encapsulating a corporate identity that can drive a strategy (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Company Core Values

Organisational values need to be enduring and so a question should always be asked: would these values change if external situations changed? If the answer is “yes” then they are not core values.

Objectives

Strategic objectives are precise measurable outcomes of a strategy. They might be sales, profits, share price, consumer satisfaction scores and so on, depending on what is central to the organisation’s purpose. In the case of Greyston Bakery, objectives would be broader based than the ones mentioned and would probably include social and environmental objectives as well.

Strategy statements

An increasing number of organisations now publish strategy statements that seek to capture what the organisation is, what it seeks to accomplish and who it seeks to serve. These statements will contain the elements listed above and also mention the scope of the organisation’s activities and the particular advantage it offers. Strategy statements should be concise in nature, some suggest less than 35 words, so that they are memorable. It is a good test of a strategy statement to count how long it is and whether it contains all the elements mentioned so far: vision, mission, core values and objectives. It may also contain an indication of the scope of the organisation and why it has, or will have, a clear advantage over competitors in achieving its aims. For instance, Coke’s scope is clear in its vision “To refresh the world” and its advantage is its scale of operations. Done well, a strategy statement can provide a useful guide to managers in their decision-making, and give confidence to employees and external stakeholders, such as investors. Done badly, a poor strategy statement might cause questions to be asked of top management competence.

Organisations may choose to articulate their purpose through one of these vehicles, or in a multiplicity of interlocking ways, like LEGO (see Figure 1.2), whose vision, mission and values clearly influence recent strategic decisions.

Figure 1.2 LEGO’s “Vision Chain”

(Source: The Strategy Builder, Cummings and Angwin (2015))

Where Does an Organisation’s Purpose Come From?

It is generally assumed that CEOs are the prime source for an organisation’s purpose and there is no doubt they can have a major influence, particularly if they are a founder or part of a family dynasty. For instance, Elon Musk of Tesla Motors and Space X, Anita Roddick of Body Shop, Steve Jobs of Apple, Steve Ells of Chipotle and Richard Branson of the Virgin group are all iconic visionary CEOs who have created successful organisations with a strong driving purpose. However, there are also examples of CEOs who have damaged their organisation through subverting its purpose to their own whims. For instance, Vijay Mallya, CEO of UB Group, an Indian conglomerate involved in alcoholic beverages, aviation infrastructure, real estate and fertiliser, diversified into Kingfisher Airlines and international markets. This seemed to onlookers as more in keeping with his extravagant lifestyle and pursuit of glamour, fitting his reputation as “King of the Good Times”, than with any obvious organisational benefits. The airline business was not competitive, leading to its collapse, and he had overpaid for international expansion leading to heavy debts and the breakup of the UB group. Other examples of “Imperial CEOs”, those that run their companies for their own purposes, include Bernie Ebbers, CEO of the telecoms giant WorldCom, who was convicted of nine criminal counts for an $11bn (£5.7bn) accounting fraud in 2005 that led to the largest bankruptcy in US history (Financial Times, 19 March 2005); Jeffrey Skilling and Kenneth Lay (Enron), Dennis Kozlowski (Tyco) and Richard Scrushy (HealthSouth) were all tried for corporate wrongdoing. Even the most fêted of US CEOs, the legendary Jack Welch, came under scrutiny, accused of excessive expenses, with a Manhattan apartment, limousine services, security guards, corporate jet and the best seats at sporting and artistic events, to name but a few. These incidents show an increasing concern for understanding and appraising the role and responsibilities of Imperial CEOs and their influence on the purpose of their organisations. It also shows that all CEOs are beholden in some degree to an organisation’s stakeholders and regulators. Therefore, fundamental questions concerning the relationship between top management and stakeholders need to be addressed.

In an Anglo-American context, the conventional wisdom is that a company should be run for its owners, the shareholders, as ultimate beneficiaries. The shareholders should then be central to forming the purpose of the organisation. However, as the opening examples show, there is suspicion that Imperial CEOs run their organisations more for themselves than for shareholders. How has this come about?

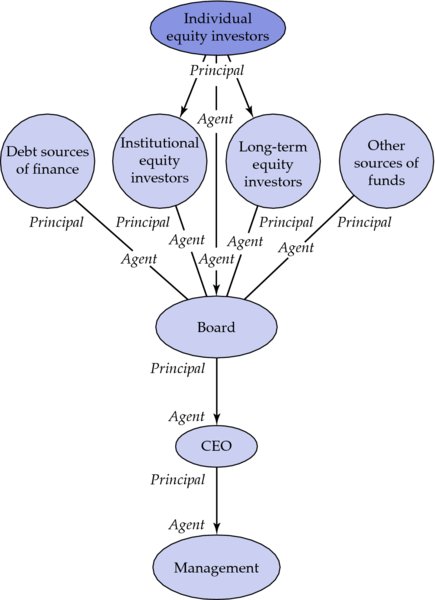

Apart from owner-managed organisations and small businesses, shareholders do not have the expertise to run the organisations in which they have ownership and so require a professional executive to manage the business for them. This means that ownership of the organisation is separated from control of wealth and results in a principal–agent relationship.1 The Chief Executive is an agent for the principal (shareholders) and is responsible for maximising the value of the principal’s investment.

The quality of the principal–agent relationship depends on the agent receiving sufficient incentive to work diligently in the principal’s best interests. For this reason, Chief Executives are highly incentivised through salary and benefits to maximise organisational performance. In this light, perhaps the benefits attributed to Jack Welch earlier are justifiable as being a small price to pay for winning the services of an outstanding Chief Executive?

Particularly noteworthy in incentivising top executives is the granting of large numbers of shares and the use of share options to align their interests with those of shareholders. The logic is that if top executives stand to benefit personally and substantially by being able to exercise their options, then they will work to improve the share price to enable this to take place and, in so doing, benefit shareholders. Of course, this method is not without problems – beneficiaries of these options may be incentivised to maximise short-term profits at the expense of the long-term future of the organisation.2

Where a problem can occur is when agents have the opportunity to benefit at the expense of shareholders. For instance, while some consumption of benefits by CEOs is likely to be beneficial to the organisation, as it may assist in attracting and retaining good managers, excessive consumption can destroy shareholder value. Former Tyco CEO, Kozlowski, was sent to prison by the Securities and Exchange Commission for failing to disclose multimillion-dollar low-interest loans (US SEC, 2002). This divergence of interests is known as an agency problem.3 Evidence can be seen in the enthusiasm for CEOs to grow their organisations, such as Vijay Mallya’s expansion into airlines. It is well known that their personal reward and prestige is positively related to the size of their organisation and so they have an incentive to increase it beyond the optimal level. The potential for overinvestment by CEOs occurs when they have access to cash flow in excess of what is needed to fund all available projects that would generate a positive return. Rather than the cash being paid out to investors4 it may be invested in projects that destroy shareholder value. To avoid the worst excesses of the agency problem there are various constraints on CEO power.

What Are the Constraints on CEO Power?

Many court cases against high-profile Chief Executives make the issue of controls on top management, or corporate governance, a very topical issue. Corporate governance focuses on whom the organisation should serve, the distribution of power and relationships among different stakeholders, and the selection and conduct of senior management. It recognises that the CEO is embedded in a hierarchy of power relationships, consisting of many different groups each with claims and influence upon the organisation. The most immediate influence on the CEO is through the chain of ownership.

In small private companies, the owners may be a small number of family members who may or may not have a role in the running of the organisation itself. While the number of shareholders may be small, the tensions and struggles between family members over the direction of the business can be extraordinary and involve issues far removed from just the maximisation of shareholder value. For larger public organisations, ownership is far more complex. Just by looking at the share register, one may well find the number of direct share-owners running into thousands of individuals dispersed around the globe. For the majority of these owners, their shares will represent only a fraction of the total issued share capital and so their individual ability to influence the organisation will be very low. Individuals may also buy into the organisation indirectly (through investment funds, for example) and may not even be aware of the companies in which they have a stake. The same applies for funds placed with pension funds under the management of trustees.

In most share registers of public companies the largest shareholders will be institutions rather than private shareholders. The investment managers of pension funds as well as investment trusts therefore have substantial influence over the organisation’s management. However other institutions, such as insurance companies, also build sizable stakes. Investment banks, for instance, may have substantial holdings in their own right, and in countries such as Germany and Japan, commercial banks are major holders of equity in leading companies.5 In these countries cross-shareholding is common, unlike the Anglo-American system, and this leads to illiquidity in dealing. It has been argued that this structural difference affects the extent to which shareholders push for shorter- or longer-term results.

Often, substantial owners of shares may be other companies, either as a pure investment or as competitors keeping themselves informed of a rival’s activities and using share ownership as a hedging strategy. It is worth noting that all of these shareholders have their own agendas and time frames. For instance, in the short term, an organisation may well have a significant portion of its shares controlled by arbitrageurs whereas pension funds may be committed for the longer term.

One type of ownership is that of the non-equity principal. These are generally banks, which, through the provision of loans and other forms of finance, such as bonds, have ownership rights over the organisation’s assets. Generally speaking, these non-equity principals become influential when there may be material changes to the nature of the organisation, in its ownership, such as when an organisation is subject to a takeover bid, or in its financing, when the organisation may be trying to raise funds. Debt holders become very significant in influencing CEOs and top management when the organisation is in poor financial health. Indeed, there can come a point where the value of the equity is virtually nil and debt holders control the organisation, wielding more power than equity holders.

The parties described above can be thought of as a chain of principal–agent relationships, with the CEO being the agent of the Board of Directors, which in turn is the agent of institutional managers and long-term investors, who are agents for trustees, who are agents for the ultimate principal, the beneficiaries (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Principal–agent chain

Between each of these links, information is passed to safeguard the interests of the principal. In the Anglo-American system, the law states that certain information needs to be disclosed to all shareholders. This is done by sending out the annual report and accounts together with notification of any material changes to the organisation. However, the richness of information obtained, over and above this legally specified minimum, is broadly proportional to the size of the shareholding and the resources available for making this collection. For instance, pension fund managers are likely to meet personally with top management, attend all meetings scheduled by the organisation and speak fairly regularly on the telephone. Individual shareholders, however, may just receive the annual report and accounts if direct shareholders, and, if holding shares through an investment fund, may not even receive this information, but simply a performance report for the fund as a whole.

Mechanisms internal to the organisation, to align the CEO’s interests with those of the owners, are financial incentive schemes. The logic is that if the shareholders become rich, then so should the CEO. These schemes may include increasing share ownership and compensation arrangements based on accounts, markets and contingencies (such as long-term incentive plans, LTIPs). While they reward CEO focus on improving selected performance measures, these techniques can be counterproductive. For instance, if a CEO’s remuneration is tied to organisation profitability, actions may be taken to boost that profitability by starving the organisation of investment for future growth. Other internal mechanisms include improving internal controls and monitoring, through (1) the performance and pay review process and (2) corporate governance (The Cadbury Report 2003). Corporate governance generally insists on the separation of Chairman and Chief Executive roles to avoid undue concentration of executive power. The Chairman is primarily responsible for managing external relations while the Chief Executive is responsible for day-to-day operations and relationships within the organisation. All Executive Directors report to the Chief Executive (but not Non-executive Directors).

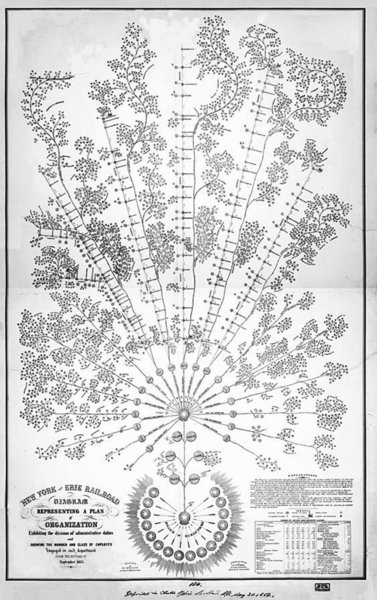

While Directors are sometimes perceived to be a cloud hovering over the organisational pyramid, this may be a function of the modern way of depicting organisational structures, which finds it difficult to illustrate the relationship between Directors and organisations. We believe that an older view might be more useful in this regard. The diagram of the New York & Erie Railroad Corporation, see Figure 1.4, depicts an effective Board of Directors as the soil from which a healthy organisational tree grows.

Figure 1.4 New York & Erie Railroad Corporation Organisation

Outside of the organisation, ownership influence can be achieved by large minority shareholders and activist investors. They have an incentive to collect information and monitor management. A prominent mover and shaker in the UK was Tony Bolton, previously a highly successful manager of US fund-managed Fidelity Group. Nicknamed “the quiet assassin”, he has been very active as an influential institutional investor, bringing about the removal of a number of CEOs. More recently when the giant supermarket Tesco was acquiring the food wholesaler Booker for £3.7bn, leading shareholders Schroders and Artisan said the deal was “distracting” of purpose – “we just don’t understand, in a business as fragile as retail, why on earth would we risk distracting ourselves from that huge goal” (of simplifying and refocusing the organisation).6

Poorly performing top executives may also be subject to a hostile takeover as a disciplinary force. The bid for Disney by Comcast was interpreted widely as a criticism of the way that Michael Eisner, Disney’s Chairman and CEO, managed the organisation. For Harvard Professor Michael Jensen, hostile bids are evidence of a market for corporate control, where executives compete for the ownership of the organisation to manage its resources effectively with a different purpose. Where a bundle of resources, or an organisation, is managed badly, better performing managers will act to replace them through a hostile takeover. This threat of takeover, which is prevalent in the US and UK systems, may be seen as a primary external means of ensuring good managerial performance.

Who Are the Other Movers and Shakers that Influence Strategic Purpose?

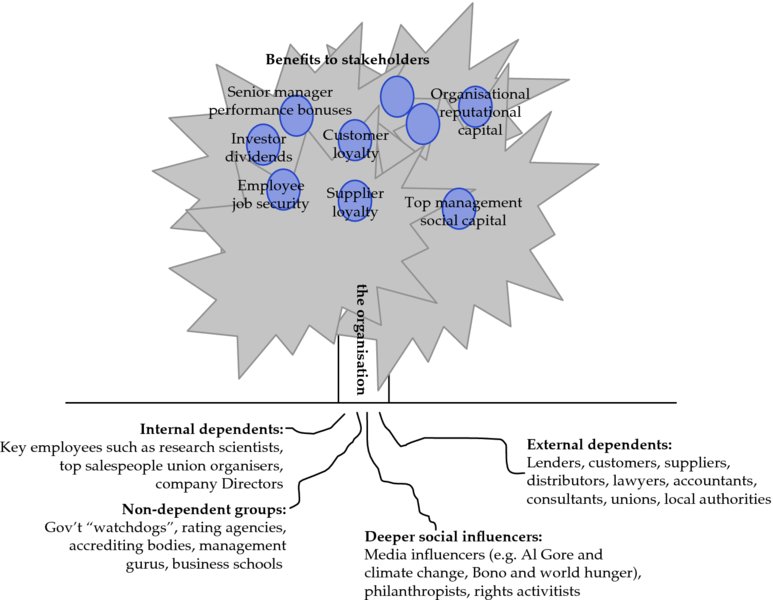

Institutional shareholders are just one type of stakeholder that influences the purpose of the organisation. There are many other stakeholders who do not have direct ownership rights over the organisation but depend on it to fulfil their own goals and are able to influence organisational strategy. A range of these stakeholders is shown in Figure 1.5. This representation is an alternative organic perspective on stakeholders as a “tree”, which harks back to some of the earliest human depictions of the relatedness between bodies (such as the Jesuit “Tree of Life”, and perhaps better captures the symbiotic relationship between an organisation and the bodies that it interacts with. The stakeholders can be seen to be the “roots” that nourish the organisational “tree” enabling it to provide them with “fruits”. Managers must tend to the roots that sustain the tree for if stakeholders withdraw their support, then the organisation will wither.

Figure 1.5 Stakeholder map

Non-shareholding stakeholders can be divided into three groups: external dependent stakeholders; internal dependent stakeholders; non-dependent stakeholders; and other, more difficult to categorise, social influencers who may shape opinions in a broader sphere which then come to impact on an organisation’s purpose and strategic choices. We describe these groups and their potential to influence an organisation’s purpose below.

External dependent stakeholders

Important external dependent stakeholders have the following relations: (1) economic (lenders, customers, suppliers, competitors, distributors) where stakeholders can influence the value creation process; (2) advisory (non-executive directors, consultants, gurus, business schools, lawyers, accountants) and (3) socio-political (local authorities, unions).

- Economic relations with the organisation can be influenced by lenders, who can withdraw funds if an organisation acts in ways that they do not approve of. Or it may be that organisations are unable to secure loans for strategies that do not fit with the lenders’ views. Substantial customers and suppliers can influence the organisation through the withdrawal of orders and supplies or the imposition of less attractive terms and conditions, such as payment terms. Competitors can influence the organisation through their actions as well as public statements of intent. For instance, Airbus Industries made public the amount of resources it put into its new super-jumbo aircraft and the contracts it has been awarding for this purpose. This “signalling” is clearly intended to influence its major competitor, Boeing, into reconsidering whether it really wants to compete head on with such a commitment of resources.

Advisory relations influence the organisation by providing ideas and solutions to problems. Non-executive directors perform an important role in having sufficient senior experience to comment on the affairs of the organisation but have no management say in the day-to-day running of the organisation. Their semi-independent status is an important characteristic to ensure impartiality, and so they should not have a commercial or other interest in the organisation beyond drawing a modest remuneration for their time. A key issue, however, is that the organisation chooses who to appoint.

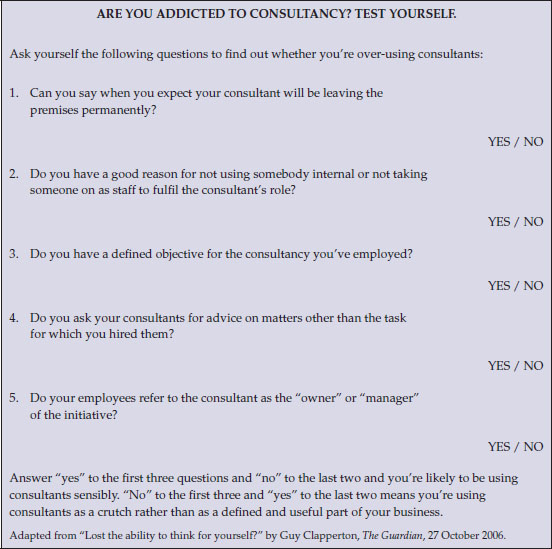

Around 90% of Britain’s top companies now employ outside consultants to advise them on strategy (a percentage that is typical throughout the Western world). These consultants are part of an industry now worth some $40bn worldwide. The executives who pull strings are also increasingly from consulting backgrounds. For instance, the alumni of McKinsey’s include the heads of America’s Boeing, IBM, Levi-Strauss and American Express; France’s Bull; Germany’s BMW; and in the UK, Asda, HSBC, Jones Lang LaSalle, Vodafone, the Confederation of British Industry and the Foreign Secretary in the UK’s Government. With their connections, consultants are able to collect impressive data and are well placed to tell organisations which companies are doing best. They perform an important role as creators and disseminators of information and, in particular, are associated with communicating “best practice”. This message is both pervasive and persuasive, although it generally relies on clients fearing being left behind in the competitive race rather than staying ahead. Many companies worry about the amount they use consultants and so we provide some guidance about whether you use them too much in Figure 1.6. The way that consultants look at strategic problems thus also influences the way their clients see the world. For example, McKinsey’s philosophy – “Everything can be measured, and what gets measured gets managed” – tends to place the emphasis on certain “hard” generic characteristics and generally leads to less of a focus on the unique “softer”, more distinctive, or less tangible, aspects of an organisation’s competitive advantage.7

- Socio-political relations can have influence at the local level through different types of business and planning regulation. Unions can influence the organisation through organising employee action.

Figure 1.6 Consultancy Addiction Test

Internal dependent groups

Internal dependent stakeholders may not have very much influence on top management and organisational purpose as individuals unless they are a particularly valued resource. For instance, they may have particular skills or knowledge, such as research scientists, have a substantial reputation that can move markets, or control a vital customer relationship. A negative example of this was the leaked emails from the University of East Anglia that threw into doubt claims about climate change. Recent research by Angwin and Paroutis8 has also shed light on significant C-level executives who are central to many change initiatives in large companies. These Senior Strategy Directors (sometimes called Chief Strategy Officers (CSOs)) deliberately interface between CEO initiatives and different internal interest groups in order to facilitate change among conflicting parties. They also have a boundary-spanning role in linking external stakeholders with multiple internal levels of the organisation, acting as critical links across different social networks. In the words of one CSO: “we are the lubricant in the machine”.9

Internal stakeholders often achieve greater power where they can group together to achieve collective bargaining power. In France, for example, surgeons grouped together and came en masse to England as a protest to the Government about their terms and conditions of work in France. Internal stakeholders may also align with an external group, such as a union, when internal grouping is insufficient to exert pressure on employers. In the United Kingdom, the current strike action of the RMT Union is severely disrupting train services in the country, and various strikes in the French airline and air traffic control industries are damaging the reputation of Air France. It is not unusual for external stakeholders to actively seek linkages with internal stakeholders to achieve their aims. For instance, suppliers may link with purchasing officers, or customers with marketing managers, to represent their interests.

Non-dependent groups

Standing above the stakeholders who are dependent on the organisation are non-dependent stakeholders, stakeholders who can influence the organisation but are not themselves dependent on it. These stakeholders include: (1) governmental bodies, which may be at the industry, regional, national and supranational levels; (2) technical organisations; and (3) opinion influencers.

Governmental bodies can influence the organisation by setting up regulators to protect interests. For instance, within countries such as the UK, “watchdog” bodies have been set up to represent customer interests. Examples include the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) for protecting the consumer and Ofwat to regulate the price of water supply. More recently, a new body has been set up to monitor the quality of schools, and has been nicknamed “Off-Toff”!10 More general frameworks have also been used, such as the Citizen’s Charter Initiative in UK public services to raise performance standards on “customer service”. In the US, Congressional legislation has been bolstered. In the wake of the collapse of WorldCom, George Bush set up a Corporate Crime Taskforce and gave extra money to the Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission to pursue corporate wrongdoers. In 2002, Sarbanes–Oxley legislation was rushed into law in response to the Enron scandal. These rules involve an annual assessment of internal controls over financial reporting and certification by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and CEO that the financial statements and accounting practices are accurate. This should remove the “aw, shucks” defence used by lawyers in Bernie Ebbers’ trial (and used by former Enron bosses), claiming that, as a former milkman with no formal training in accounting, he was incapable of spotting fraud. Although the amount of detail required to satisfy this legislation is perceived as extremely onerous for US companies, it does force them to “comply or explain” and there is evidence that investors are demanding such explanations.

There are also international bodies that monitor standards, such as Transparency International, which publishes a “perceived corruption index” of countries. This sort of information can influence the decisions of organisations to invest abroad and the extent to which they might risk trading in such areas.

- Technical organisations can influence the organisation where independent credit rating agencies, such as Standard & Poor’s, can directly affect the ability of the organisation to raise funds through the direct costs of borrowing as well as influence on share price. BP Horizon’s oil spill crisis in the Gulf of Mexico caused its credit rating to be downgraded as investors wondered whether the organisation could survive the pressure being put on it by the US Government for massive financial compensation. Other standards agencies may determine appropriate technology standards for a market. For business schools, there are several accreditation agencies, such as the AACSB, AMBA and EQUIS, which exert significant influence on the strategies that can be followed by MBA programmes, for instance, through the promotion and policing of global standards. These can all influence an organisation’s purpose.

- Opinion influencers can have an impact on the organisation’s purpose by providing the latest ideas and concepts. Here the role of gurus, consultants and business schools is well documented. The power of thinkers such as Clayton Christensen, Sumantra Ghoshal, Gary Hamel, C.K. Prahalad, Michael Porter and David Teece, and ideas such as the Boston Box, Best Practice, Blue Ocean Strategy, Bottom-of-the-Pyramid and the Business Process Reengineering to influence management initiatives is clear to see in both profit and not-for-profit organisations11

Other social influencers

In addition to these three main groups of non-shareholding movers and shakers, there are a number of less categorisable opinion influencers that good strategists should not ignore. These include campaigners for broader social issues, such as fighting poverty in Africa. High-profile media stars like Bob Geldof and Bono have organised events, such as Band Aid and Live 8, which propel issues onto the public stage. Through tireless campaigning, Geldof among others is attempting to influence the banks of the First World to rescind African debt. Underlying such campaigns is a strong view of what is right and ethical behaviour for companies. While it is by no means clear that everyone agrees on what is “right” and “ethical” behaviour, as the world consists of very diverse cultural norms and beliefs, there are mounting pressures for socially and environmentally responsible behaviours to be viewed as synonymous with good management and embedded in an organisation’s strategy. This “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) point of view is gaining ground and echoes the achievements of Greyston Bakery mentioned at the beginning of the chapter. There is growing evidence of organisations now producing CSR documents and altering their purpose as a consequence of a backlash from, for instance, consumers disapproving of the use of child labour.

CSR focuses on the embeddedness of the organisation in a wider set of social conditions and recognises that business affects society as well as depending on a set of social conditions, such as quality of workforce, government regulation, etc., to be able to operate and compete. Michael Porter suggests that, at the generic

How Can Different Stakeholder Interests Be Managed Strategically?

Achieving some alignment between expectations and interests of different stakeholders is critical for an organisation’s purpose. Organisations that try to set a purpose that stakeholders will not buy into are likely to struggle. However, this can be highly problematic as stakeholder interests will differ and often be in conflict. The classic conflicts that may exist include:

- Short-term results to suit equity markets versus long-term investments to secure the future success of the organisation

- Improvement of efficiency versus substantial job loss

- The need for professional managers versus the loss of family control

- Reduction of costs versus providing a social necessity

- Public share ownership versus need for more openness and accountability

- Operating locally in one country versus parent ways of operating and expectations located in a different country.

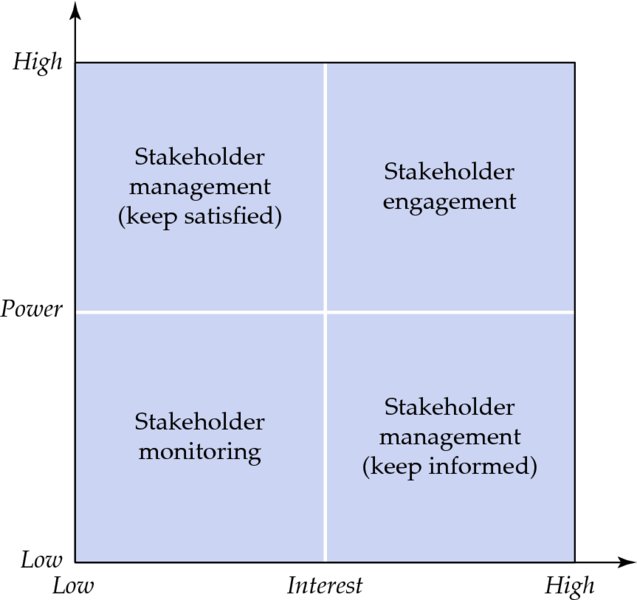

Conflict among stakeholders can be particularly difficult to manage in not-for-profit situations, where there can be much greater diversity amongst stakeholders and the interactions among them. The greater diversity of providers, resources, recipients and public/private values produced and a richer set of interactions with the environment all serve to present formidable challenges to not-for-profit senior managers (see Live Case 1–4 on Britain’s National Health Service at the end of this chapter). Nevertheless they, like all organisations, need to make decisions (and not doing anything with regard to stakeholder conflicts is still a decision and generally not a very good one!). It is useful, therefore, to map these multiple interests to understand political priorities. This can be done using a power/interest grid, which identifies the level of power a stakeholder has to influence the organisation and the level of interest they have in supporting or opposing a particular strategy (see Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Power/Interest Matrix

(Source: The Strategy Builder, Cummings and Angwin (2015))

By debating the positioning of different stakeholders and categorising them graphically on the power/interest matrix, it becomes possible to identify which ones are likely to be key supporters or blockers of a strategy and to create priority lists, action plans and to engage in scenario thinking (see Chapter 2). Moreover, it can help sharpen the best means of communicating with them, i.e. whether to inform them moment by moment in person before a decision or by general circular after one has been taken.

A major weapon in this regard is lobbying, and most major companies employ specialists, such as public relations officers, relationship managers or stakeholder relations managers, for the purpose of understanding and potentially influencing key powerful interested parties such as governments and legislators. Lobbying also exists on a much more micro level as a direct activity, carried out person to person – such as wining and dining a favoured client – as well as an indirect one, creating alliances with support groups or significant people in order to bring pressure to bear on a specific stakeholder.

Categorising stakeholders on the power/interest grid raises issues of how to manage those who have power and interest. Through the careful use of information, bartering or negotiation, objections that these stakeholders may have to a strategy may be removed on the grounds that concessions are given on other fronts. This can raise ethical issues for top managers over whether they are, or should be, weighing up the conflicting expectations of stakeholder groups; whether they are answerable to one group, and then work to make those interests acceptable to others; or whether they are really acting in their own interests and managing stakeholders to suit their own purposes.

Who Determines Strategic Purpose?

CEOs are often linked directly with setting the strategic purpose of an organisation and are accountable for the strategies that are pursued. However, this chapter has shown that CEOs are various in nature, ranging from self-determined Imperialists to politicians manoeuvring skilfully between powerful conflicting forces. They can also be good agents acting faithfully in accordance with shareholder wishes or bad agents motivated more by self-interest.13 In most cases, though, CEOs are embedded in a complex ecosystem of stakeholders all with different agendas and different degrees of influence. It is this mix of stakeholder interests that should determine the purpose of an organisation.

Also, it is worth noting that the power and interests of different stakeholder groups to influence an organisation and its CEO can change over time. Recent research14 has begun to question the primacy of shareholders in for-profit organisations in Anglo-American business models, and in other parts of the world primacy is not given to shareholders, with some governance systems explicitly recognising the importance of employees in workers’ councils, for instance. Nevertheless, there is still evidence that CEOs may listen more to some stakeholders than others, by sanctioning the cutting down of mature forests or releasing dangerous toxins in order to maximise shareholder wealth.15 The interplay between institutes of directors, lawyers and business schools in communicating and educating boards of directors on their real roles, as well as the sanctions of regulators, are key influences upon CEOs, the purpose of an organisation and how this is acted out.

In short, strategy starts with a purpose and this will reflect the opinions of stakeholders of which the most influential is generally the CEO. Strategic purpose requires us to adjust the commonplace configuration of “ready, aim, fire”, to “aim, ready, fire”. While tools like SWOT and others that we will describe in the following chapters can help us to strategise by analysing contexts (Chapters 2 and 3), identifying key competitors and competitive strategies (Chapter 4), determining critical resources and capabilities (Chapter 5), selecting appropriate business models (Chapter 6), suggesting ways of organising (Chapter 7), highlighting strategic growth options (Chapters 8 and 9), and ways to change the organisation (Chapter 10) to achieve success (Chapter 11), they may not help us create effective strategies if we don’t know what the point of these strategies is. If strategy is about winning then organisations must first understand what winning means for them, or what winning looks like. Martin Luther King had a dream. LEGO’s purpose is clear. John F. Kennedy set in motion strategic thinking and science that is difficult to replicate to this day by capturing the imagination with the aim of sending man to the moon. Elon Musk, whom you can read more about in the cases that follow, is aiming to enable humans to reach Mars by 2033. Ben & Jerry’s brownie bakers, Greyston Bakery, want to create jobs for their community, and they strategise accordingly. As a German proverb says: “What’s the use of running if you are not on the right road?”

What’s your dream? What’s your aim? What’s your strategic purpose?

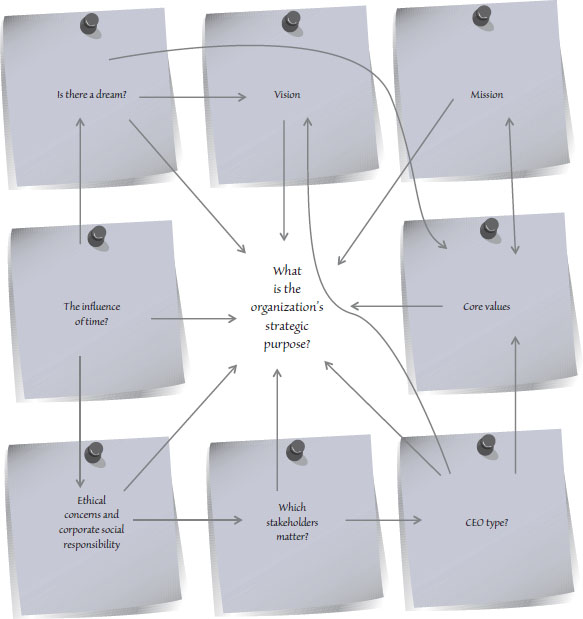

Strategic Purpose Key Learnings Mind-Map

At the end of each chapter (before the live cases), we provide a collection of sticky note shapes for you to outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter. Annotating these notes and drawing lines between them to indicate relationships are ways to remember, interpret and think through the issues in the chapter. In this, the first chapter, we’ve got you started by providing some suggestions, but in the following chapters, these note pages will be left blank for you to fill in.

1-1 Tesla: Electric Dreams

Any environmental analysis of the strategic environment facing the automobile industry performed over the past two decades would have identified the threat of an over-reliance on fossil fuel powered vehicles and the opportunities for vehicles powered by alternative forms of energy. And yet, auto companies have been slow to take up these opportunities.

Elon Musk is not the only person to argue that the inertia is the result of a lack of willingness on the part of established companies in the industry to move away from their reliance on fossil fuels. But Musk did something different about it. He built an auto company that only made electric vehicles.

Born in South Africa, Musk moved to Canada (where his mother was born) when he was 18 years old. He studied at Queens University in Ontario, then transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a degree in physics and a degree in economics. In 1995, Musk moved to California to begin a PhD in applied physics and materials science at Stanford University, but he left the programme after just two days to pursue his entrepreneurial ideas.

One of these ideas grew into PayPal, the electronic payments company, and by 2002 when this was sold to eBay for US$1.5 billion in stock, Musk became that company’s largest shareholder, owning 11.7%. The sale gave Musk the financial clout to pursue loftier ambitions.

Musk is variously described as a business magnate, management guru, engineer and inventor and has, at various points in his career, been all of these things simultaneously. At his three largest corporate initiatives since PayPal – Tesla, Solar City and SpaceX (see Live Case 1-5) – he is at once co-founder, CEO or Chairman, and Product Architect or Chief Technology Officer (CTO). He has stated that the goals of SolarCity, Tesla and SpaceX revolve around his vision to change the world and humanity. And his grand ambitions include reducing global warming through sustainable energy, and reducing the risk of human extinction by making life multi-planetary.

Elon Musk was ranked the 94th wealthiest person in the world in 2017, with an estimated net worth of $13.9 billion. In 2016, Musk was ranked 21st on Forbes’ list of the World’s Most Powerful People. In 2015, he starred in The Simpsons as himself (i.e. an archetypal business revolutionary/mad scientist). Mr Burns confuses him with Henry Ford. Since the death of Steve Jobs, Musk has become the first name that comes to mind for many people when they think of maverick movers and shakers in the world of technology and business.

Tesla Motors was incorporated in July 2003 by Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. The company was named after the maverick inventor Nikola Tesla, who had an ongoing battle with Thomas Edison for dominance in the early years of electricity research and commercialisation (which the more corporate-friendly Edison won), and whose original ideas about alternating current (AV) influenced the development of Tesla vehicles.

Musk partnered with Eberhard and Tarpenning to raise funds for expansion and the commercialisation of their first car in 2004 and joined Tesla’s Board of Directors as its Chairman. Musk took an increasingly active role within the company and oversaw the design of an electric sports car called the Roadster. The Roadster hit the market in 2008, the same year as the Global Financial Crisis, and the same year that Musk assumed full leadership of the company as CEO and Product Architect, which he retains to this day. As of the end of 2016, Musk owns about 28.9 million Tesla shares, or 22% of the company.

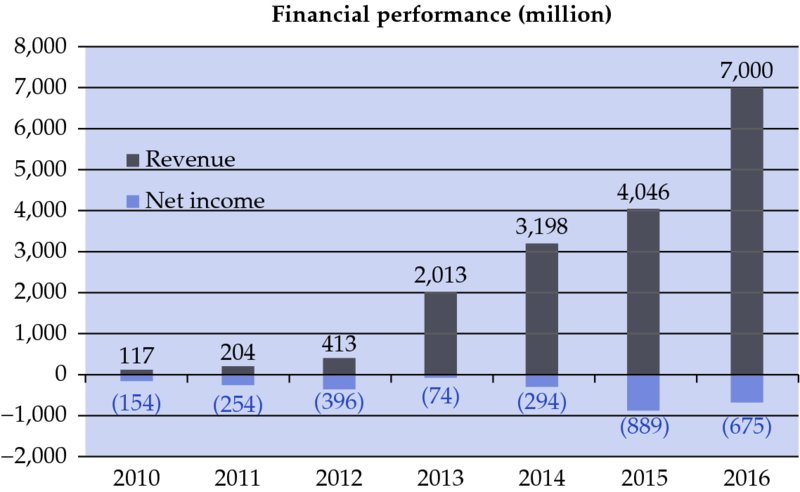

The Roadster was a modest success with sales of about 2,500 vehicles to 31 countries in 2008. But since then, with the follow-up four-door Model S sedan launched in 2012 (which has become the World’s 2nd best-selling electric vehicle), the Model X SUV and investments in new production plants and infrastructure such as a network of charging stations across the US and Canada, Tesla’s production and revenues (although not its profits) have risen steadily (see Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 Tesla revenue and income

Being so deeply involved in the development of Tesla and its products has led to Musk lashing out at those who don’t share his vision. He took the BBC television show Top Gear to court in 2008 for “libel” and “malicious falsehood” in relation to host Jeremy Clarkson’s review of the Model S. The courts found in Top Gear’s favour in the libel case and the falsehood claims were also struck out, with the presiding judge describing Tesla’s malicious falsehood claim as “gravely deficient”. And, in early 2013, Musk berated the New York Times across social media for a less-than-favourable review of Tesla’s charger network.

Perhaps realising the limits of this testiness and Tesla’s maverick stance, Musk and his company have adopted softer positions more recently, partnering with traditional auto companies Daimler and Toyota to produce electric powertrain systems for their vehicles and Panasonic to produce batteries. It has even teamed up with accommodation provider Airbnb to provide Tesla chargers at their properties. And, perhaps most dramatically, Musk has recently offered to make all of Tesla’s innovations available to any individual or organisation with good intentions to advance his aims for the development of sustainable energy.

What the future holds for Tesla remains uncertain. Can Musk grow the company’s market share and increase profitability? Will electric cars prove to be just a fad? Will the established auto companies gradually nibble away at Tesla’s innovations and incorporate them into their own business models? Will the company’s willingness to share their knowledge erode any advantage they have?

But no matter what the answers to these questions turn out to be, there can be no doubt that Musk has done his best to shake up the automobile industry and point it in a new direction.

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

The slow development of electronic cars, despite the fact that their technical feasibility has been proven for many years, may be attributed to the fact that the key players in the automobile industry (i.e. those stakeholders that have the interest in and power to shift strategies in this field) are still living out the dreams of the original founders of the industry, such as Henry Ford. (Recall his vision, described in this chapter, to “[d]emocratize the automobile” and “make it accessible to every American … The horse will have disappeared from the highways and the automobile will be taken for granted”, which was a classic – for its time.)

In order for things to change, Musk will likely need to connect a new purpose and vision for the future to a new set of key players. Ask yourself who those new players might be? From what industries or institutions might they come?

The advantage is that Musk is a maverick, he is not a traditional key player in the industry and so doesn’t have the vested interest in past investments that others do. This means that he can use his energy, fresh thinking, innovation, financial resources and celebrity power to promote a different vision without compromising his traditional interests (the same cannot be said of the auto industries’ traditional big players). Musk has the power to push things through without having to seek approval from a traditional Board of Directors or other stakeholders.

The disadvantage is that, without the influence, advice and control of other parties with different perspectives, Musk and the company are vulnerable if his ideas turn out to be too far-fetched or not fully cognisant of the opportunities and threats in the industry. A strong Board comprising people with more industry experience could, therefore, advance Tesla’s purpose as well as hinder it. It is a difficult strategic balancing act that any analyst should be mindful of.

On the surface, Musk’s dream for Tesla might appear to be to sell more electric cars. But as the company has evolved so have Musk’s aims. The need for reliable and longer-lasting power sources has broadened the company’s purpose, leading to more overlap with Musk’s other personal and business interests in sustainability: both as it relates to energy generation and human beings’ ability to survive looming macro-environmental shocks like climate change in the centuries to come.

Reading the last case in this section on SpaceX and doing a little further research on Musk’s other interests might help you get beyond the obvious superficial answer to this question. Having done a bit more research on Tesla, Musk’s role within the company and his other interests, how would you describe Musk’s strategic purpose for Tesla?

![]()

1-2 NZ Police: Safer Communities Together

The New Zealand Police have a reputation as being one of the least corrupt law-enforcement bodies in the world. Up until the early 1990s, this simple ethos or mission guided them:

“To work with the community to maintain the peace.”

Generations of policemen and women took great pride in living up to this ideal.

However, as was often the way with public service organisations in the 1990s, the New Zealand Police Force was increasingly encouraged to become more “professional”, to employ modern management thinking to bring it into line with approaches used in the private sector. The Force was urged to utilise external consultants to help it move closer toward “best practice”, to develop more rigorous methods of managing performance and be seen to be more “accountable”.

One of the first services that such consultants generally offered was the creation of a new mission statement. Hence, after much development work, 1992 saw the launch of NZ Police’s new mission:

“To contribute to the provision of a safe and secure environment where people may go about their lawful business unhindered and which is conducive to the enhancement of the quality of life and economic performance.”

Curiously, while the later statement is five times longer it says no more of substance than the first (indeed, by making no mention of how, or by what strategy, its stated aims should be achieved – contrast “To work with the community” with “To contribute” – it says less). In addition, the second statement is far less memorable and more confusing in terms of how it might be operationalised.

According to members of the Force it was not a great success. Many police officers on the ground now claim that it confused rather than guided them and admit that they paid little attention to the new mission, instead continuing to look up to the earlier statement and the ethos that it embodies. It is perhaps not surprising then that recent years have witnessed a reappreciation of simpler times. The New Zealand Police’s new vision is: “Safer Communities Together”, which says more or less the same as “To work with the community to maintain the peace”. However, it is even easier to paint on to the side of a police car!

1-3 LEGO: The Power of “Clutch Power”

In 2017, LEGO was named the world’s most powerful brand (ahead of Disney, Apple and Visa) by the global valuation consultancy Brand Finance. This topped off what has been a remarkable rise for the Danish-based company, following becoming the world’s largest and most profitable toy company in 2014. In addition to these financial achievements, its social capital had risen so high that it could release what critics termed a 90-minute commercial called The LEGO Movie and charge people money to watch it.

The director of the movie, Chris McKay, was upfront about this: “It’s ultimately a 90-minute toy commercial when you take a step back and look at it,” he explained. “But LEGO’s one of those brands that people don’t have a negative feeling about.” In fact, The LEGO Movie was more than just a toy commercial. Films have subtly promoted toys before (think of the real toys that are the stars of the Toy Story series, for example), but The LEGO Movie was remarkable in that it was not just an ad for its toys but the philosophy and vision of the company that made them as well.

And people lapped it up: it was the UK box office’s highest-grossing film of the year and it spiked demand to the extent that there were shortages of the actual toy the following Christmas. There can be no doubting the power the LEGO brick now. Yet just over a decade earlier the company nearly went out of business. What happened?

In 1916, a Danish carpenter, Ole Kirk Christiansen, started a small workshop in Billund Denmark. The shop burned down and when it was rebuilt Christiansen turned part of the new premises into a shop for the toys he had started making. He came up with the name LEGO, from the Danish phrase leg godt, meaning “play well” and by the 1930s, Ole was known for his LEGO pull-along toys made from birch wood.

In 1947, Ole was visiting a toy fair when he saw a plastic moulding machine. Ole bought one and used it to press plastic versions of his wooden toys. Later, in conversation with his son Godtfred, he had a different idea: making a system of plastic bricks would enable kids to experiment and design their own toys – and the possibilities could be endless.

The initial bricks made by Ole were great for stacking, but they had room for improvement. The solution was what came to be called “clutch power”. This was the aim and the result of the patented studs and tubes design that Ole and Godtfred developed. A system that enabled bricks to be easily but firmly stuck together, pulled apart and then stuck together again. The LEGO system of play was born and continues to this day. (In fact, bricks made in 1955 still work with bricks you can buy today.)

The simple idea of clutch power is at the heart of LEGO’s success. According to Jon Sutton, editor of The Psychologist, LEGO has such intrinsic appeal, for both creative children and adults, because it “represents both order and chaos. You can follow the instructions step by step, or you can go off-piste and create pretty much anything you can imagine.” It’s the combination of both of those possibilities that give LEGO its appeal. And while the LEGO system did not catch on quickly initially, when the company went international in the late 1970s it found that the market was global. LEGO experienced fantastic growth from 1978 until 2003. And then it crashed.

Initially LEGO executives couldn’t see what had gone wrong. But loyal LEGO customers could. LEGO had incorporated different themes into their toys since the 1980s, but over time the toys became more about the theme than the clutch power of the brick. By the 1990s, lured into following other plastic toy companies like Mattel, LEGO toys contained less and less interchangeable bricks and more moulded structures that could not be re-imagined into different forms by the kids (and, increasingly, adults) that bought them. LEGO had forgotten the importance of clutch power. LEGO’s loyal customers had not. And they would show LEGO what they needed to do in their reaction to a new LEGO product.

At this time, the problem (and the solution) was manifest in a new LEGO toy called Mindstorms. LEGO Mindstorms toys came with a brick programmed to convert a built toy into a robot that could then move in the ways that LEGO’s program instructed it too. Many LEGO fans (particularly young adults) bought Mindstorms products, but then they hacked the LEGO program and reprogrammed the software to do different things. Recall that this was in keeping with the original LEGO clutch power philosophy: you could stay true to the original integrity of the instructions or you could go “off-piste”. But LEGO appeared to have forgotten this and, worried that the hackers were messing with their intellectual property, began to engage legal advice and have serious, stern-faced discussions about what could be done to protect the company from these external threats.

Fortunately, before they went too far down this path, LEGO rediscovered their identity.

A LEGO executive explains how it unfolded in a documentary film called LEGO: The Brickumentary:

For us this was a great opportunity, because we saw a great potential of combining LEGO and computers. LEGO had in mind that they would develop it, and then kids would play with it in the prescribed way, and they had as an audience children, their standard, traditional audience. But it really sort of captured the imagination of people of all ages … Then there was someone who liked LEGO who was at Stanford and was like, “Hmm, this brick, I could hack that open and reverse engineer it.” And they were opening up the Mindstorms. They were writing new software for it. Within three months, a thousand hackers were working on it. And this was rather a shock for them. LEGO’s response was pretty much like, “What is this?” They’re taking apart what we created. I mean, we put this together, so it shouldn’t be taken apart. That’s our secret. There was a lot of questions in our leadership. We could either take the aggressive and protective and controlling route, and the other route would be to say well, this is, uh, interesting. In most companies, and also in a very traditional way of innovating, it was kept super-secret. It’s like closed walls, sign on the “X,” and we couldn’t say anything. We had a lot of internal discussions with our lawyers, top management was involved. [But Chief Executive and Ole’s grandson] Kjeld [Christiansen] had to stand up and say, “But I want this. We’re a company who makes things that people can create with.” When a company starts to deal with users, and discovers that it can get ideas from users, that’s Mindstorms. That’s the new way of saying, you will [interact with your community] and you will get from them useful ideas. We need to be aware that 99.99% of the smartest people in the world don’t work for us.

Mindstorms was the turning point where LEGO rediscovered what made it successful. Rather than resisting creative ideas from its customers, it embraced and then encouraged and facilitated their development. Mindstorms hacking became a community movement. LEGO took advantage in the growth of interactivity the internet has allowed to cheer on and capture the enthusiasm and great ideas from its fans. It has now launched Kickstarter-style “LEGO Ideas” websites (e.g. www.ideas.lego.com; www.cuusoo.com) where people can propose new sets and innovations that will be considered for production if it can create enough interest among other LEGO fans.

This interactivity did not damage the company: it made it stronger. It has made users feel they are both attached to the LEGO family and its success and independent creative thinkers, and enabling these two things together has engendered even greater loyalty. Moreover, it has led to the production of a number of cool new series generated by fans such as LEGO Architecture and the LEGO Bird project.

The rediscovery of its mojo is now reflected in how the pieces of the company’s identity statement slot together: LEGO’s Values are: Imagination/free play, Learning, Fun, Quality, Caring, and Creativity; its Mission, to “Inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow”; its Vision “Inventing the future of play”; and LEGO describes its culture as about being “purpose driven”, “systemic creativity”, “action-ability” and “succeeding together”, all joined together by a keystone brick: that says “clutch power”.

In 2017, 70 years after Ole Christiansen bought that plastic moulder, LEGO fans were eagerly awaiting the release of a new LEGO movie: a sequel, of sorts, called The LEGO Batman Movie.

The choice of LEGO Batman – the least heroic of super heroes – as the main character for its next film shows, according to some commentators, that LEGO has learnt its lesson: it doesn’t take itself too seriously or see itself too rigidly any more. Early reports had toy stores around the globe stocking up for the consequences.

1-4 The NHS: Merry Men and Virgins

As a means of demonstrating how students of strategy, like management consultants or any other stakeholders, can bring assumptions based on their own experience to bear on problems that may require a different mindset, we often use a little exercise based on Robin Hood and his merry men. Robin has a problem, which is described below. The question we pose to students is: Robin has hired you as a management consultant; what would you advise him to do?

Robin Hood’s revolt against the Sheriff of Nottingham began as a personal dispute. But Robin knew that he could do little to exact his revenge without the help of others. So, he set out to find allies – men with similar grievances that he could unite under a common cause. He did not have to look very hard, and as he looked back on the first year of his operation he was still surprised at how quickly he had gathered around him able men who shared his personal hatred of the Sheriff and his overlord – the brutal Prince John, who ruled, unjustly in Robin’s eyes, in the absence of Richard the Lionheart.

There had been little structure or routine to the establishment of the band of merry men that had emerged. Robin asked few questions of his charges and their motives and only required that they trusted his ultimate decision-making authority and gave their all in pursuit of what had become their motto: “Rob from the rich and give to the poor.” Under Robin’s rule, a simple structure had evolved, with particular tasks delegated to those who Robin saw as his most able lieutenants, such as Will Scarlett, Little John and Friar Tuck.

But, as the legend of the merry men spread, so the number of recruits from further afield increased. Some came with a taste for adventure; others with a desire, or need, to live outside of the law. As the band grew larger, what was once but a few tents was turning into an established camp with an increased range of ancillary services attached. More and more men spent more and more time sitting around waiting to be organised and waiting for adventure. The cost of maintaining this organisation was on the rise.

In the meantime, revenue was declining. The rich were becoming more adept at avoiding capture by Robin’s less than nimble organisation and the Sheriff and Prince John were becoming more skilful in anticipating and combating Robin’s raids. Moreover, in response to Robin’s opposition and stirring up of the region’s common folk against them, they had worked hard to shore up their own defences and political alliances, so as to make their overthrow – which had, at one point, been Robin’s driving ambition – increasingly difficult.

As he moved into the second year of his campaign, Robin was confronted with some difficult problems. Was his strategy effective? How should he organise his forces? What did he need to change and what should he seek to retain? One thing was clear, however: he did not know the answers to these problems himself. He would need to consult with others. “Perhaps,” he mused, “I could benefit from hearing more about the latest thinking in these domains.”

Students don’t tend to begin by imagining the particular “macro-context” within which Robin operates before thinking of solutions that would fit with this. Hence, they tend to unthinkingly provide modern answers to Robin’s problems. For example, from a modern management consultant’s perspective, what Robin should do is decentralise, devolve responsibility, empower those beneath him or franchise. However, in Robin’s cultural setting – where his forceful, charismatic, almost divine leadership is the core that holds everything together – such solutions would likely be seen as a sign of weakness, that Robin is losing his “mojo”, or that he is no longer committed to the cause. They would likely leave the organisation in a greater state of malaise than when the consultants came in.

Many believe that a similar overlaying of generic solutions that did not take account of the particular operational context occurred when consultants from the Virgin Group, famous for revamping maturing consumer product and service markets like air and rail travel, cola, vodka and banking, were called in by Government ministers to write a report on Britain’s hospitals at the beginning of the year 2000. In an article in The Sunday Times, the Secretary for Health, Alan Milburn, described Britain’s publicly funded NHS (National Health Service) as “a 1948 system operating in a 21st century world. That is why,” he explained, “I have now asked Sir Richard Branson’s award-winning Virgin Group to advise us on how hospitals can be made consumer friendly. It is about transforming the very culture of the NHS to make it a modern consumer service.” Press releases claimed that the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, would use the report to follow up on accusations made by his Health Secretary of the dire “forces of conservatism” within the NHS and “the gross inefficiencies built into the system”.

The consultants visited nine hospitals and several GPs’ surgeries over a 26-day period and composed a damning report. They wrote of “over-centralisation”, “too much red-tape”, “chaotic booking-arrangements” and “poor management”. They concluded that “the patient is required to fit into the system, rather than the other way around”, and that the “dead hand of bureaucracy seems to stifle imagination and flair”. However, on the up side, they claimed that “most [staff] are probably decent people who just need a little leadership and direction”. The actions they believed should be taken to remedy the situation included the sort of ideas that have become commonplace in many organisations: “empowering workers to be more innovative”, making hospitals more “consumer friendly” and increasing transparency and accountability. (One recommended means of doing this was to allow patient representatives to go behind the scenes and carry out “snap inspections”.) There was also talk of snack trolleys and making hospitals “more fun”.

However, NHS employees were critical of the Virgin report and the Government’s handling of it. Doctors felt they were being blamed for poor public perception of the NHS, which, they argued, was caused by lack of funding. Stephen Thornton, the Chief Executive of the NHS Confederation, accepted that declining standards needed to be addressed but challenged “the Virgin team to show me what they describe as a suffocating bureaucracy. Where on earth do they get ridiculous figures that imply there is one administrator to every two clinical staff?” Of all NHS staff, only 3% were managers/administrators, compared with 44% nurses, 8% doctors and 17% clerical, he said, asking “I wonder how many backup staff it takes Virgin to get one pilot into the air.” In any case, he continued, “many administrative and clerical staff undertake critical patient-related tasks. It is disingenuous to suggest these people hinder rather than help the treatment of patients.” Peter Hawker, Chairman of the British Medical Association’s Consultants’ Committee, similarly suggested that he was “all for improving the services to patients but we need real resources, not an exercise in spin [doctoring]”.

These criticisms sparked a wider debate about the Blair Government’s use of consultants. A survey by the Independent on Sunday showed that it had spent almost a billion pounds hiring private consulting firms in its first three years in office. It was revealed that The Department for Education and its agencies spent almost £10m between 1997 and 1999. In response, Nigel de Gruchy, General Secretary of a prominent teaching union, claimed that “[t]he money could be much better spent. The Government paid Hey McBer consultancies £3m to come up with criteria for what makes a good teacher. We could have told them that for nothing.”

The Department of Health’s spending on consultants in the same period was two and a half times that of Education. According to one source, this could have paid for 2,327 heart bypass operations, 4,421 hip replacements, 737 full cancer treatments, and the wages of 1,133 junior doctors. A spokeswoman for the Unison health union said: “It’s an awful amount of money to spend on consultants, particularly if those consultants are at the expense of money going into front-line care. We generally know what the problems are, the difficulty is getting the Government to listen to the people who are on the ground.”

The ensuing media attention has led to increasing scrutiny of the way in which management consultants are used in the UK and similar scrutiny has been applied in many countries around the world as to how much consultants can cost, and the value they can bring. And it is increasingly the case that popular culture, in the form of TV shows like House of Lies, has poked fun at organisations’ overreliance on consultants. The Robin Hood exercise and the NHS example can help you to understand why.

1-5 SpaceX: Falcon Rising

Elon Musk was introduced in the first case in this chapter which outlined how he and his company, Tesla, have sought to shake up the auto industry. As mentioned in that case, another key component in Musk’s vision and strategy for making human life more sustainable is his company SpaceX. It is SpaceX that is aiming to reduce the risk of human extinction by making life multi-planetary. But in advance of that aim, it is seeking to change space exploration more generally and that requires making space travel itself more sustainable by creating renewed interest in space exploration, making it more accessible and more cost effective.

Most commentators would agree that in the past two decades, since the decline of the “space race” between the Soviet Union and the United States and the reduction of the Space Shuttle programme, the space industry has lost its impetus. In the United States, the demise of the Soviet state made it harder for successive governments to “sell” to taxpayers the incredible costs associated with growing the space programme. The reduction in the perceived threats associated with not staying in front has diminished the sense of urgency and the space programme does not engender the same levels of national interest and pride that it did in its heyday. But where others saw an industry in decline, Musk saw a unique set of opportunities.

Musk, like many modern inventors, had been an enthusiast of space exploration since he was a child and when he moved to the United States was disappointed to find that interest and funding for NASA and space exploration generally was waning. He conceptualised a project he called Mars Oasis to enable the growth of plants on Mars as a way of rejuvenating interest in the value of space exploration and part of his earlier stated aims with regard to advancing the sustainability of human life.

In 2001, at an early stage of the project, Musk went to buy rockets from Russia, thinking (perhaps naively) that he might be able to secure some good deals as that country’s space programme was still struggling after the disintegration of the Soviet state; but getting the cheap rockets he wanted proved more difficult than he had hoped and he had to return empty handed.

On the flight home, a disappointed Musk started to sketch out an alternative plan. As far-fetched as it sounded at first, perhaps he could build the rockets he needed himself?

He knew that if he started with the smallest and simplest orbital rocket needed for putting simple payloads (e.g. satellites) into space the raw materials would only cost a fraction (about 3% according to Musk’s calculations) of buying rockets on the open market.

Moreover, more complex state-of-the-art rocket ships not only came at greater expense, they came with greater risks: for a new company like the one Musk was envisaging, an early failure could lead in bankruptcy, terminally damage the image of his brand and enable the naysayers to claim that they were right.

Musk also knew that the decline in the space industry was having a knock-on effect on all of the contractors that helped build the parts that went into rockets for NASA. They were struggling and they and other expertise based in the southern United States could perhaps be vertically integrated into a very cost-effective new company too. Local governments keen to improve the economies and employment prospects in their region would also be interested in helping out, he imagined.

And whatever waning interest there might be for more advanced space exploration, there was certainly no decline in demand for increased global communications and the satellites that facilitated this.

By taking advantage of these opportunities and adopting a modular production approach used in software engineering, Musk estimated that he could cut the cost per launch cost by a factor of 10, sell payload delivery to customers at well under what was being charged by the market leaders, and still enjoy a 70% gross margin.

The recognition of these opportunities eventually became the company named SpaceX, which was incorporated and launched in 2002 after Musk hired renowned rocket engineer Tom Mueller (SpaceX’s CTO of Propulsion).