5

Resource-Based Advantage

This land is me: rock, water, animal, tree; they are my song.

Aboriginal tracker in the Australian film One Night the Moon by Kev Carmody

#Ilovebarca! Spend any time at all in the Catalan city of Barcelona and you’ll sense a special relationship between its citizens and its football club, Barcelona FC. That team is them and they are a part of the team. The city has a spring in its step the morning after a win (especially against Real Madrid!). And even if the team suffers from a bad run of form, while Barcelona’s citizens will complain, they will never allow outsiders to criticise. The team is like family.

While a football team may be an extreme example of how deep roots and connections are an important part of an organisation’s strategic DNA, we are beginning to develop a greater recognition of the importance of historical relationship between organisations, their stakeholders and their locations. From phone makers, to auto companies, to craft brewers, organisations everywhere are now seeking to appreciate and understand how their history and their relationships with stakeholders and other assets can be seen as valuable and rare strengths – unique inimitable strengths not easily circumvented by their competitors.

This is a different perspective from the view of how an organisation develops strategic advantage from that outlined in the previous chapter. In the chapter on Competitive Advantage, the strategist was like a designer who could make whatever moves he or she thought best given the environmental conditions. Here, the strategist is also a custodian of the resources that he or she inherits. And more than this, the strategist should look to an organisation or its personnel’s historical background and relationships for strengths upon which to grow strategic advantage. However, whether the approach is Competitive Advantage or Resource-Based Advantage, the purpose is the same: what strengths should we draw upon to take advantage of environmental opportunities in order to win. The present chapter on Resource-Based Advantage provides you with a broader set of frameworks and ideas on which to draw upon to do so.

The idea that organisations can have deep roots that connect them to people, a community, a region or a nation, and that these connections are a competitive resource, is not a new one. But it is one that mainstream strategy thinking is only just starting to comprehend and credit. Two strands of literature have intertwined in the past few decades to promote this more organic view of what provides an organisation its strategic advantage. First, from organisation theory comes a focus on the importance of culture as both a source of competitive advantage and the “glue” that holds an organisation together as it seeks to develop the other forms of competitive advantage that we covered in the previous chapter and in the two following chapters on Business Model Advantage and Corporate Advantage. Second, is a view of developing strategic advantage by focusing not just on material strengths (things, in other words – often listed as nouns), but on an organisation’s relationships with these resources and capabilities (or what we might categorise as actions or activities).

We start by exploring the importance of culture, both organisational culture and national or regional culture.

Culture

Organisational culture as a basis of competitive advantage

The focus on how culture can be a source of advantage entered the mainstream strategy literature in the late 1970s, as people began to question what had enabled Japanese companies to emerge as such a potent force.

Books appeared urging Western managers to embrace Japanese management practices such as kaizen (continuous improvement) and quality circles (and, subsequently, total quality management (TQM)), approaches that had emerged out of a distinctive Japanese way of thinking and doing: a way that emphasised community, harmony, slow patient increments (rather than “quick fixes”) and a long-term view.

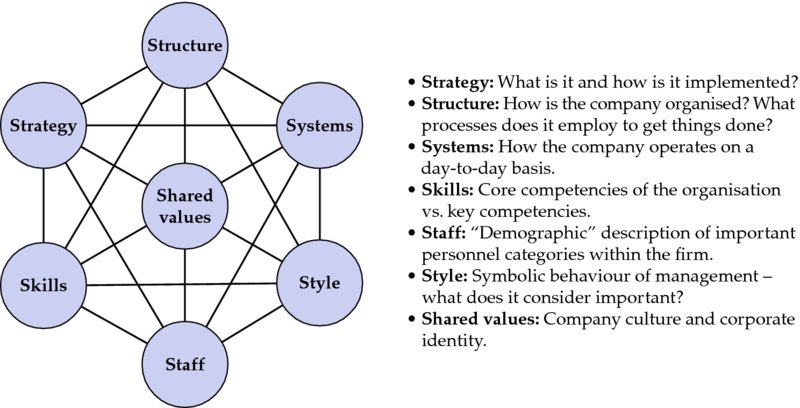

Perhaps the most widely used framework for understanding culture – the “Seven Ss” – was developed at this time (see Figure 5.1). Hatched by four McKinsey & Co. consultants (Anthony Athos, Richard Pascale, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman), the Seven Ss formed the basis of Pascale and Athos’s book, The Art of Japanese Management. This argued that whereas US managers focused on strategic plans, organisational structures and systems of control, Japanese managers embraced the “soft Ss” – a concern for staff, skills development, their corporation’s style and greater or superordinate goals (which would later be rephrased as “shared values”).1 This, according to Pascale and Athos, was why Japanese companies were more successful than those from other nations.

Figure 5.1 McKinsey’s 7-S framework

(Source: adapted from Pascale and Athos, 1981)

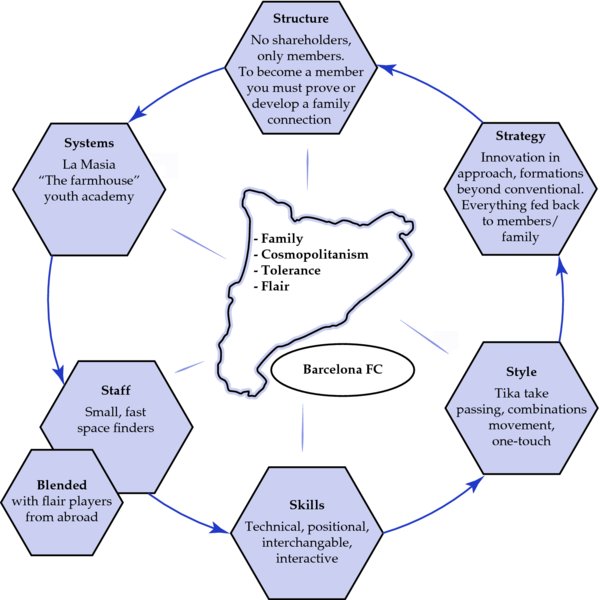

We can apply the Seven Ss to better understand the cohesiveness and strength of Barcelona’s culture. Figure 5.2 shows the Seven Ss “in action” in this regard. The organisational structure in which the club is owned by its members (either those with a family connection to an existing member or by somebody from anywhere in the world who wants to make a presentation outlining their love for the team and how they share its values), reinforces a sense of family and loyalty. This is reinforced by systems such as the La Masia youth academy where young players are treated as family and looked after by mother and father figures. Most of the playing staff come from this family academy, but they are blended with players from elsewhere who are deemed to share the values of the team and play with the Barca brand of skills and style. All of these elements are reflective of what are seen as the best aspects of the Catalan spirit and values: family, tolerance, flair, cosmopolitanism. Put all these things together and the strategies that the team must follow become obvious: nobody has to think too hard about what to do to help Barca win both on and off the pitch. And those strategies with their deep connection to the community breed both success and tremendous loyalty.

Figure 5.2 The Seven Ss applied to Barcelona FC

(Source: Cummings and Angwin (2015), Strategy Builder (New York: Wiley))

Figure 5.3 The cultural web

(Source: adapted from Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin and Regner, 2017)

Building on the success of Pascale and Athos’s application of the Seven Ss to Japanese management, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman used the framework as a basis for learning about the characteristics of high-performing firms. They found that successful firms emphasised the softer Ss, particularly shared values.2 In their famous book, In Search of Excellence, they claimed that these firms tended to exhibit a particular type of culture, namely one that exhibited eight traits: a bias for action; being close to the customer; valuing autonomy and entrepreneurship; emphasising productivity through people; being hands-on and value driven; sticking to what they know best; having a simple structure and lean workforce; and being simultaneously centralised and decentralised.

Time has seen many of the companies that In Search of Excellence promoted fall by the wayside. And subsequently many of the specific traits the book advocated (e.g. sticking to what they know best and having a simple structure) came to be regarded as problematic as general strategic rules. However, others have built on those elements from In Search of Excellence that have stood the test of time to fashion other alternative cultural “guidelines”. For example, Chris Bilton and Stephen Cummings suggest that successful creative organisations tend to exhibit:

- A strong, but adaptive, culture

- Meritocratic politics

- “Deutero” learning (learning that questions established ways of thinking)

- Drawing on good ideas from inside and outside the organisation

- A multitasking workforce

- Ambidextrous architecture (i.e. a combination of open plan and traditional office space)

- Poise (i.e. they are not static or frenetic but are always poised for change when it is required to maintain environmental alignment).

Another useful framework for analysing the components of a corporate culture is “the cultural web” developed by Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin and Regner (2017) (see Figure 5.4). This covers much of the same ground as the Seven Ss, but its additional focus on stories, rituals and symbols is particularly valuable for strategy analysts.3

Figure 5.4 The Porter Diamond of International Competitiveness

(Source: adapted from Porter, 1990)

The “symbols” of an organisation are broad ranging (e.g. from the clothes staff wear, the logo or brand, to the buildings in which the organisation is housed) but particularly telling with regard to culture. For example, much has been written on how the dominant architecture of a period characterises the sensibilities of a particular society, and for organisations it is no different: an organisation’s architectural choices say a great deal about the organisation’s identity. Sir John Harvey-Jones, the famous British television management guru, once commented that an experienced observer can tell a great deal about the culture of a firm by entering and looking at their premises. For instance, if one went to almost any town in the UK during the early 1990s, bank branches were grand affairs located in prestigious high street positions, with ornate stone exteriors and beautiful interiors of rosewood-panelled counters, marble floors and expensive brass fitments, all symbolising permanence, prosperity and importance. If one looks at the stunning new steel, chrome and glass buildings in big cities today, many occupied by professional service firms, a strong message is being stated. (We shall explore these ideas further in our final chapter on Maverick Strategies.)

Peters and Waterman concluded that “without exception, the dominance and coherence of culture proved to be an essential quality of excellent companies”, a finding endorsed by Collins and Porras’s more recent investigation in Built to Last, which went on to claim that the key factor in sustained exceptional performance is a culture so strong that it is not dissimilar to a “cult”.4 However, a culture that is so tightly knit can be both a curse as well as a blessing. While a strong unified culture can help people to act quickly and efficiently, it can blinker companies from rethinking their assumptions as the environment changes, as we explained in Chapter 2, and present difficulties when needing to integrate with other companies. Duncan Angwin (2007) reports high failure rates when two organisations come together through merger or acquisition or other forms of inter-organisational alignment such as joint venture.5 These failures are commonly attributed to culture clash – a contest for dominance by one culture over another.

Attempts to characterise organisational cultures turned over much fertile ground and caused a whole generation of managers to take what Peters and Waterman described as the “softer side” of strategy seriously; there emerged a tendency to believe that there was one best type of culture. This led to attempts to ape Japanese approaches in the West, approaches that only made sense within the deep context in which they emerged, and attempts to try to insert new culture into organisations as one might insert a new carburetor or air conditioner into a car.

Needless to say, most of these attempts failed, and when the new culture did take hold it generally succeeded only in making companies more like those they were competing against – something that goes against one of strategy’s main tenets of being distinctive and runs contrary to what a focus on resource-based strategic advantage should bring to a business.

The strategic value of national context and culture

So far, we have focused on how particular organisational cultures can imbue companies with valuable and difficult to imitate resources.

Beyond contrasting American and Japanese cultural practices that led organisation theorists and strategists to focus on culture as a source of competitive advantage, Dutch academic Geert Hofstede examined the cultures of 53 different nations and categorised them according to five dimensions of: (1) power–distance, (2) individualism versus collectivism, (3) masculinity, (4) uncertainty avoidance and (5) long-term versus short-term orientation (these are described more fully in Chapter 9, Crossing Borders).6

These different orientations can be seen to affect many things that relate to strategy: from the type of management theories that one nation develops or favours (Hofstede was particularly concerned to show how American management theories might not apply outside of the US), to the way staff behave and develop and implement strategy, to a particular nation’s customer values. Herein lies an explanation for why a company’s advertising for cooking products will show male and female partners cooking together in the Netherlands while the same ads are adapted to feature two female friends in Germany;7 and why some argue that Marlboro cigarettes were more successful in Asia than Camel because the Camel symbol represented a lonely figure whereas the Marlboro cowboy was implicitly part of a group.8

Perhaps the best-known framework for analysing how a nation’s context, and the identity that stems from it, can influence a region’s natural competitive advantage is The Porter Diamond.9 Michael Porter and his team of researchers at Harvard developed The Diamond of International Competitiveness as a means of better understanding why, for example, the best watches seem to come from Switzerland, the first computer companies were American, why Hong Kong might be a key financial centre (see our Strategy Builder book for a case study on this) or the best equipment for racing yachts might be made in New Zealand. He claimed that the answer lay in distinctive background provided by the interrelationships between the following four contextual elements that make up the corners of the diamond:

- Context for firm strategy and rivalry (vigorousness of competition)

- Demand conditions (whether customers are sophisticated and demanding)

- Factor conditions (quality and cost of factors such as labour, natural resources, capital, and physical infrastructure), and

- Presence of supporting industries (is there a critical mass of capable suppliers?).

And two outlying, but important, elements (see Figure 5.4):

- Government strategy (government can influence all four of the major factors listed above through subsidies, education policies, regulation of markets and product standards, taxes and antitrust laws), and

- Chance (which can nullify advantages and bring about shifts in competitive position through new inventions, wars, shifts in world markets and political decisions).

Using Porter’s framework we can explain, for example, why many of the world’s great beers come from Belgium (Table 5.1). The constellation of these elements, which have emerged over time to provide the context within which Belgian brewers operate, is unique and inimitable. No other region’s contextual background provides quite the same positive environment for so many breweries making great beer.

Table 5.1 The national context underpinning Belgium’s competitive advantage in brewing

| Factor conditions | Belgium’s breweries lie close to some of the best natural ingredients for beer, while long established apprenticeships and training programmes, combined with the traditional high status afforded brewers in Belgium, ensures a good supply of quality human resources. |

| Demand conditions | Beer is Belgium’s national drink and consumers are consequently knowledgeable and discerning. They will not tolerate bad beer. |

| Related and supporting industries | As mentioned above, Belgium’s breweries benefit from close proximity to quality hop farmers. Moreover, with the major cost involved in selling a bottle of beer being distribution, it helps that Belgium is a hub for many major distribution networks and companies. |

| Firm strategy, structure and rivalry | There are perhaps more breweries per capita in Belgium than in any other country. While they are all fiercely competitive, they also have a history of collaborating when in the collective best interests. |

| Government strategy | The Belgian Government has supported the beer industry throughout many centuries. It has supported the industry’s training programmes and its low-excise regime for beer makes it very inexpensive in Belgium relative to other parts of the world. More recently, the Belgian Government has actively sought to become the centre of the European Union. |

| Chance | Belgium happens to be well placed as a lynchpin between major powers such as France and Germany (see above) and at the centre of the world’s greatest beer-consuming bloc – Europe. |

While the elements that make up the Porter Diamond might reflect the harder or more economic side of corporate identity, we might gather together the softer, but no less influential, aspects under the heading of culture. There have been innumerable attempts to define culture. These range from Geert Hofstede’s austere “culture is the collective programming that distinguishes one group of people from another” to Linda Smircich’s plainly put “culture is the specific collection of values and norms that are shared by people in a corporation that control the way they interact with each other and with stakeholders outside of the corporate body”.10 However, it is unlikely that any definition has approached the clarity of the colloquial expression that culture is “the way things are done around here”. And any analyst seeking to develop strategy for an organisation ignores the way things are traditionally done in that organisation at their peril.

Resources and Capabilities

The emergence of the Resource-Based View of the firm

The emergence of “the Resource-Based View” of the firm (RBV) has changed the way that we think about how organisations strategise, compete and evolve.

The theorising behind the RBV is not new. Many trace it back to Edith Penrose’s (1959) book The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. This is not an easy read (so we are not recommending reading it all), but it is important to recognise that it sets out most of the concepts often hailed as new insights by authors in the 1980s/90s.

Another antecedent of the RBV is the work of Henry Mintzberg in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Mintzberg highlighted that effective managers did not start with a blank sheet of paper and design strategies. Rather, good strategies “emerged” organically as managers sought to build upon and reconfigure existing characteristics and relationships.

Subsequent work by the likes of Wernerfelt (1984), Rumelt (1984), Barney (1991) and Peteraf (1993) refined and developed these ideas and defined RBV as a particular approach to strategy development: that the competitive advantage of a firm lies primarily in the application of a bundle of valuable tangible or intangible resources at the firm’s disposal. Transforming a short-term competitive advantage into a sustained competitive advantage, they argued, requires that these resources are heterogeneous in nature and not perfectly mobile. The consequence being that an organisation’s most valuable resources are neither perfectly imitable nor substitutable without great effort, and these resources are very often organic, interconnected and relational rather than discrete and material.

Generally speaking, resource-based theories of the firm see an organisation as a collection of firm-specific resources, organisational routines, capabilities and competencies. And it is these often intangible, organic, difficult to define and hard to replicate aspects that explain inter-firm differences in competitiveness, as well as inter-temporal dynamics, or the evolution of businesses and industries.

By focusing on active or emergent “capabilities” and organic relational attributes as opposed to static objects as sources of competitive advantage, the RBV and Mintzberg’s work encouraged some to shift focus from seeking to articulate strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in adjectives and nouns, to describing a firm’s competitive attributes in active verbs.

RBV proponents emphasise that competitive advantage stems from the uniqueness of a firm’s resources. Resources here has a wider meaning than the usual tangible factors of production such as plant and equipment, things that can often be touched and measured, and more intangible assets like brand. It also includes the various capabilities/competencies11 the firm possesses for exploiting existing resources such as the innovation capabilities of Apple, the marketing capabilities of McDonald’s and the design capabilities of Swatch. In other words, the processes that are applied to assets in order to create value. Moreover, the business’s abilities to learn, improve and to change these capabilities, to enable the exploration of new un-tapped resources, are also part of its long-term resources.

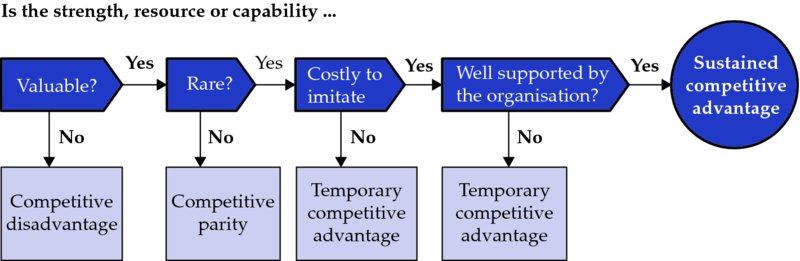

For a resource to offer long-term competitive advantage, it must have three key characteristics; it must be:

- Competitively superior and Valuable to the consumer.

- Rare.

-

Difficult to Imitate.

- Organisationally supported, in order to appropriate or extract value from the resource.

Valuable?

To be valuable, a resource must fit with the “Critical Success Factors” of the industry. However, to be competitively superior it must do so better than the resources of its rivals in meeting customer needs. It must increase value through higher perceived value to customers, encouraging them to pay higher prices or make their offering attractive through lower prices than the competition, achieved through volume production. Dominos are good at making and delivering pizzas but no better than their opposition and so it is only superior marketing that can offset the trend towards low price as the default strategy in the delivered pizza industry. The problem in this industry is that great marketing capabilities are still at the mercy of the 2 for 1 pricing offer as these pricing attacks must be matched. Therefore, in order to achieve competitive advantage, resources must be valued uniquely by customers.

Rare?

The competitive advantage from a valuable resource will be short-lived if that resource is not rare. Some physical resources are actually rare; sometimes due to natural circumstances such as with viable, low-cost oilfields or due to government fiat such as with the champagne-producing region of France. In the main, however, physical rarity as a durable competitive advantage is itself rare. Organisations may own unique technologies and have private knowledge that are not available to others. They may also have distinctive capabilities that allow organisations to create value and are not visible to external competitors. These may give organisations a competitive advantage. Often though, organisational resource bases are composed of valuable but common resources and capabilities. These are necessary for competitive parity but will not be sufficient for competitive advantage.

Inimitable?

The most common threats to rarity lie in the standard competitive dynamics of imitation and/or substitution by another resource offering the same benefits to the user/consumer. Over decades the fabled Toyota Production System (TPS), a complex organisational capability in quality and cost control, gave that company a significant productivity advantage over its US competitors. However, the gradual dissemination of knowledge enabled the others to imitate the TPS. So, in 2007, Chrysler was achieving the same person-hours per vehicle rate as Toyota (37.3), with Honda, GM, Nissan and Ford less than 3.5 hours per vehicle behind.12 The pressure of the chasing pack eventually told on Toyota as the company was forced into humiliating and costly recalls in 2009/10 – the fable had ended.

If legal blockages cannot be established through patents or copyrights, then imitation can only be prevented or slowed if a number of isolating mechanisms13 are in place to protect the valuable capability. Such isolating mechanisms include the following:

- It is expensive to develop (e.g. semi-conductor fabrication planets) and/or

- It will take a long time and involve a lot of prior learning (path-dependency) (e.g. Coca-Cola’s branding expertise) and/or

- There is little understanding of the processes underlying the capability even in the business with the capability (causal ambiguity). For example, Southwest Airlines’ low-cost capability; everyone knows the parts – the internet booking system, the fast plane turnaround, the lack of on-board services etc.; these have been extensively examined, written about and imitated. However, the implicit, cultural “glue” that makes up the whole, and which is much more the key to financial success, has proven much more difficult for its US rivals to copy.

The threat of substitutes is an industry-level force we discussed earlier in this book and is normally couched in terms of replacement of products (e.g. plastics as a substitute for steel). However, resources can diminish in value as substitute capabilities emerge. For example, the big broking houses found that their in-house capability for research and analysis in stock investment became less valuable as low price, internet broking-only services encouraged investors to do the research themselves. Buyers developing the expertise and doing it themselves is an ongoing substitution threat to in-house capabilities in any expertise-based industry like education, consultancy, brokering, house repairs, estate agency, restaurants, etc. Even the physical scarcity of large, low-cost oilfields won’t sustain competitive advantage if high prices encourage the development of viable substitution by other energy sources such as nuclear, solar and/or wind power or hydrogen cells in cars.

Organisationally supported?

A resource can only underpin competitive advantage if the value from that resource can be gained (“appropriated”) by the organisation. If the resource is an individual or group of individuals then almost invariably a bargaining process begins between the firm and those individuals for the value created. The ongoing threat to the firm is that their human resources can be tempted away by other firms or can set up in opposition themselves. This dynamic is most obvious in professional sports teams, financial firms, consultancies etc. where the star players garner more and more of the income for themselves. Look, for instance, at the transfer fees for top footballers in the Premier League and then how many of their football clubs are actually making large profits. However, the increasing size of remuneration packages for CEOs of large corporations across the Western world suggests that more value is being appropriated by the stars of the boardroom who can leave to manage the competition if their wants are not met. Note that the size of the remuneration package is bearing less and less relationship to company performance and more and more to the perceived rarity value of the star. Unfortunately, shareholders pay for the star but not necessarily his or her best game.

There are many examples of organisations that had rare and valuable resources but were not organised in a way to extract value from them. For instance, Xerox had the resources and capabilities to create a desktop computer but were firmly fixed on the photocopying industry, thus allowing Bill Gates to seize the opportunity. Kodak invented the digital camera and yet focused on the ageing photo film industry, leading to the demise of the company. Laker Airways spotted an opportunity to launch low-cost transatlantic flight but couldn’t organise itself effectively enough to succeed, leaving it to Richard Branson and Virgin Atlantic to seize this initiative some time later.

You can think of the idea described above in terms of the acronym VRIO as a checklist (see Figure 5.5). We believe it is extremely useful to distil the strengths, resources and capabilities that might typically emerge from a SWOT analysis down from a long list of potentially strategic focal points to a more focused list of key capabilities that should form the basis of an organisation’s strategy. Work through your list asking whether these are things or activities: Valuable (do they fit with customer’s key needs?); Rare (are they easily obtainable by customers from elsewhere?); Imitable (can they be easily copied or substituted by alternatives?); are they Organisationally Supported (can they be exploited by the organisation in order to obtain value?).

Figure 5.5 VRIO as a resource-based advantage checklist

(Source: adapted from Cummings and Angwin (2015), Strategy Builder (New York: Wiley))

The Evolution of Dynamic Capabilities

As the relationship between resources and effective strategy development was examined further in the 2000s, the concept of dynamic capabilities (DCs) emerged. DCs are essentially second order strengths and capabilities: those capabilities that enable adaptation through the development of new strengths and capabilities. Hence, the concept is particularly useful for organisations actively seeking to grow, either through acquisition, where the aim is to acquire good targets and add value to these acquisitions, or organically, by building on existing capabilities and growing new ones.

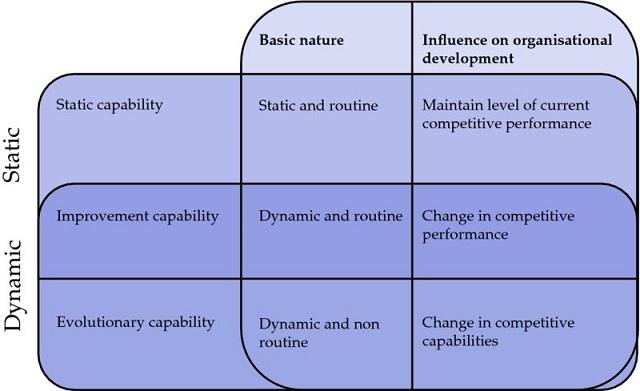

Dosi et al. (2000) outline three levels of capabilities that help explain how dynamic capabilities (DCs) are different from traditional strengths and capabilities:

- Static capabilities are like strengths in that they affect a firm’s current level of competitive performance, but are active rather than static. So, for example, a firm’s strength might be “having cash in the bank”, whereas a capability might be “the ability to act fast when faced with investment opportunities”

- Improvement capability, which affects the pace of competitive performance improvements into the future (e.g. “an ability to sense good investment opportunities, act quickly, and effectively integrate them into the existing business”), and

- Evolutionary capability, which is related to the accumulation and development of the new static and improvement capabilities that change the resource base of the firm over time (e.g. “a culture that values informed discussion and evaluation of innovative investment opportunities and the ability to understand how these might influence future developments”).

While (ii) improvement and (iii) evolutionary capabilities can both be regarded as dynamic capabilities, they are different in that the latter are non-routine meta-capabilities that continually renew and refresh an organisation’s capabilities. However, when taken together we can say that dynamic capabilities are those capabilities that enable the development of future growth and change. The three orders of organisational capability are summarised in Figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6 Three levels of capabilities

In recent years, a great deal of emphasis has been placed upon learning more about how dynamic capabilities can affect firm growth and performance and be better understood and implemented, as these are believed to:

- Have the greatest impact on the firm’s survival for the long term as they are closely related to the business environment, and ensure that as the environment changes the organisation adapts and evolves with or ahead of it

- Be the most difficult capabilities for competitors to copy or replicate, and

- Are likely to be small in number, so will enable greater strategic understanding and awareness of them throughout the firm and clearer focus in decision-making.

However, it is important to note that a focus on dynamic capabilities should not detract from understanding and developing an organisation’s capabilities. Rather, firms should seek to develop a good understanding of both.

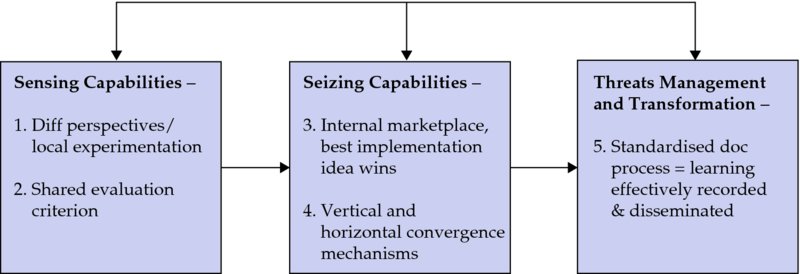

In our opinion, the most useful framework for thinking about DCs in relation to particular corporations in a way that can aid strategy development and option taking is the sequence of David Teece and his co-authors: SENSING→SEIZING→TRANSFORMING, where an organisation’s dynamic capabilities are divided into a series that follows the generally accepted “explore→exploit” pattern of successful strategic growth. This framework is shown in Figure 5.7.

Figure 5.7 Three types of dynamic capabilities

(Source: adapted from Teece (2007), Three Stage Dynamic Capabilities Framework)

In practical terms, the purpose of exploring the notion of dynamic capabilities and the Sense-Seize-Transform sequence is to develop a model for understanding a firm’s most strategic capabilities, an understanding that can help, in combination with an analysis of environmental trends, better evaluate which growth and development options to pursue. How they work in action may be seen by examining the case of Toyota.

Toyota’s rise since the 1970s is well known and many analyses of this success have focused on identifying the strengths or capabilities that have driven the company. For example, a reasonably sophisticated analysis of Toyota’s success might include the following capabilities:

- Adoption of skills from historical partners (e.g. supplier networks), competitors (Ford) and other industries (aircraft, locomotive, bicycles, textiles)

- The deployment of the entrepreneurial and innovative vision instilled by founders Kiichiro Toyoda and Taiichi Ohno

- Japan’s relative technological deficit in technology by contrast with the West encouraged Toyota to look for “human” approaches to increase quality and cost-effectiveness

- Systematic pressure for productivity improvements through approaches like TQM, JIT and kaizen became ingrained in the Toyota culture

- Traditional resource shortages meant that the company became good at simultaneously reducing costs and increasing quality.

This is a good list and goes a long way to describing Toyota’s historical success. But it is not a particularly unique set of attributes; it does not explain how the company has changed and evolved over the past three decades; and it does not explain what will drive the new Toyota in the decades to come. To analyse that we need to also think about Toyota’s dynamic capabilities. Key to Toyota’s evolution and adaptation as the business environment has changed have been the following DCs:

- The continual encouragement of different perspectives and local experimentation, from people from a variety of backgrounds and industries, in problem-solving, future-scanning and options development discussion

- A shared understanding of how all problem solutions and development options will be evaluated

- An internal marketplace within plants for ideas about how production can be best executed where a meritocracy means that the best idea wins

- Organisational mechanisms that encourage convergence around implementing the best ideas vertically (up and down the plant) and horizontally (across to other plants and suppliers)

- Company-wide standardisation of documentation processes ensures that learning is accurately recorded and disseminated and feedback is timely and effectively embedded.

When taken together, these DCs help explain Toyota’s mantra of “Learn local, act global” and its paradoxical twin watchwords of continual “expansion” and continual “integration”. And they may be usefully organised into Teece’s SST framework, as illustrated in Figure 5.8.

Figure 5.8 Toyota’s three stage dynamic capabilities

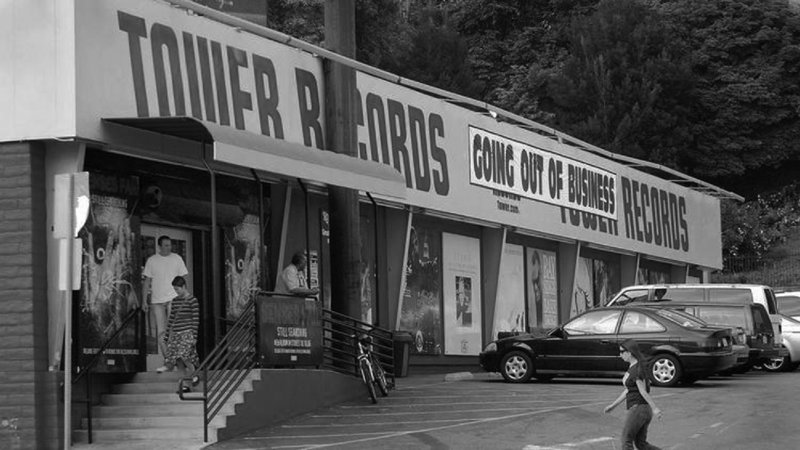

Figure 5.9 Tower Records store in Los Angeles

Figure 5.10 Artists discussing their music at Tower Records’ Shibuya store in Tokyo

Knowing the importance of these dynamic capabilities means that Toyota can continue to utilise, emphasise, nurture and invest in them.

The Future of Culture, Resources and Capabilities as Sources of Strategic Advantage

Recently, there’s been a lot written claiming that “culture eats strategy for breakfast” (Google the phrase for more on this). The implication is that culture is more important than strategy; or that strategising is a waste of time as an organisation’s culture will overwhelm it. However, it is worth noting that the idea that organisations have a unified culture is a concept invented by strategists.

The strategy behind the creation of culture as an important thing in management is linked to strategy consulting firm McKinsey & Co. responding to the rise of a key competitor, Boston Consulting Group, who were winning new business with their BCG Framework in the 1970s. McKinsey deployed a team of consultants to Stanford and Harvard to work with professors to develop a framework of their own that they could brand. This framework became the McKinsey Seven Ss framework which we described at the beginning of this chapter.

But where did the Seven Ss in the distinctive seven-node snowflake diagram come from? Pascal, Athos, Peters and Waterman have been a little vague about this. But a small monograph called Organizational Dynamics written by J. P. Kotter, also from Harvard (we’ll examine his theories of organisation transformation in Chapter 10, Leading Strategic Change), contains diagrams which bear a striking resemblance to the Seven Ss (although some of Kotter’s nodes would be altered by the McKinsey people) so they started with Ss (alliteration is good branding!). So if somebody tries to convince you that culture is more important than strategy, or that culture eats strategy for breakfast, you can recall that it was a clever strategy that created culture (or at least the way we tend to think of it) in the first place.

In any event, however, we believe it is better to think of culture as a key part of strategy rather than something different from it. What we have covered here in this chapter on Resource-Based Advantage is just the tails (or roots) side of the strategy coin, whereas what we described in the preceding chapter on Competitive Advantage is the “heads”. Both are important, inseparable, and so should be seen and used in combination.

What we now know is that the long-term superior performance of an organisation depends on how much better, relative to its rivals, a firm’s strategy utilises its strengths, its resources and capabilities, in relation to environmental forces. Key are its skills in developing and marshalling unique resources to maintain and improve its competitive advantage. Macro-shocks such as significant technological advance, e.g. electricity, the telephone, the internet and nano-technology, can batter down the existing advantages of incumbents but, in the main, advantages are slowly eroded anyway by the prevailing winds of imitation and substitution. The driving quest of all organisational strategy therefore must be for the development and maintenance of unique resources and capabilities that support a valuable competitive position, and to avoid as far as possible imitation and substitution. In this sense, the less tangible are those unique resources and capabilities – such as history, culture, ways of doing things – the harder they are to imitate. The distinctive culture surrounding Barcelona FC, for instance, described at the beginning of the chapter, is a good example of the power and durability of this capability. And yet even this is unlikely to provide a unique advantage in the long term unless it evolves. Dynamic capabilities, as sources of organisational renewal, therefore matter as you have to continuously draw upon and invest in many strengths, resources and capabilities, to evolve with the environment and stay ahead of the pack!

Resource-Based Advantage Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

5-1 Tower Records: A Tale of Two Towers

By the year 2000, Tower Records had become a company earning one billion dollars a year. Five years later it was bankrupt. On the surface, the demise of an iconic record store chain seems easy to explain. The rise of cheaper and faster ways of accessing music through streaming made it impossible for a chain of bricks and mortar retail stores to survive.

Except that this logic does not account for one thing. Whereas the Tower Empire – which stretched from the United States to the United Kingdom, from Thailand to Ireland to Israel – folded like a CD case after Tower in the US came down, one Tower survived – and has subsequently thrived: Tower Japan. For each of the last 10 years its 85 Japanese stores have brought in close to $US500 million per annum.

So what makes Tower Japan different from Tower in the US and its other subsidiaries?

Russ Solomon started Tower in his father’s drugstore which shared a building with the Tower Theatre on Watt Avenue in Sacramento in 1960. Seven years later, Tower Records expanded to San Francisco, opening a store in what was originally a grocery. This was the start of a US-wide growth programme. Arguably the most famous Tower store was purpose built by the company in 1971, on the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Horn Avenue in West Hollywood, with many staff personally contributing their labour to the build. The chain eventually expanded internationally to the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Ireland, Israel, United Arab Emirates, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Argentina, and Tower stores diversified into selling books, posters, plants, electronic gadgets, video games and toys.

A child of its time, Tower became the coolest place in America to be and the coolest place to work, evoking a “community of outsiders” atmosphere that is captured in films like Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity. As Bruce Springsteen says in a recent documentary by Colin Hanks that charts Tower’s decline (called All Things Must Pass www.towerrecordsmovie.com): “Everybody in a record store is your friend for 20 minutes.”

In describing Tower’s US heyday, Hanks’ documentary relays how working at Tower was a non-stop party “so long as you did the work”. There was, unusually for the time, no dress code. A former employee, rock star Dave Grohl, describes how working at Tower was perfect for him as it allowed him to keep his long hair.

Solomon’s whole approach to human resourcing with the Tower “family” was unique. In All Things Must Pass he explains that every manager in the company started out by working in the store, and he called his managerial style “the Tom Sawyer method of management”. “I always got someone else to paint the fence,” he explained. “Everything we ever did was based on ideas from people in the stores.” Subsequently, most decisions in those expansion years seemed to have a “seat-of-the-pants” character to them. This led to what the film describes as a period of unprecedented success, decadence and an adolescent feeling of fearlessness and invincibility in the company.

A big part of the community vibe was the free music magazine with reviews and interviews written by staff called Pulse!, which Tower began publishing in the early 1980s. Initially, Pulse! was given away free in stores, but in the mid-1990s a decision was made to distribute the magazine nationally with a cover price of $2.95.

As the 1990s wore on, Tower started to show signs of growing pains. The rapid expansion had left it heavily indebted, there was greater competition on the high street and they were slow to respond to changes in the industry. In hindsight, they were overly confident that their cool image would trump changes in technology and new rivals like Napster and allow them to keep the price of CDs high.

Japan was Tower’s first international foray. In 1979, Tower Records Japan (TRJ) started its business as the Japan branch of the MTS department store. The following year the first Tower store was opened in Sapporo. TRJ spread the same ethos as their US parent, hiring staff who loved music and promoting a club-like environment where young people could feel a part of a music-loving community.

One important advantage that TRJ had relative to the other Towers around the world in the turbulent 2000s was that local management seized on the opportunity for a management buyout as the parent experienced its first wobbles in 2002. This gave TRJ management the freedom to chart its own course. It invested heavily in re-developing its landmark Shibuya store in Tokyo in 2012, making it one of the biggest music retail spaces in the world (it covers 5,000 m² and nine floors and is regularly listed as one of the world’s “must see” record stores).

TRJ also publishes three free magazines aimed at specific audiences: Tower, Bounce and Intoxicate, with staff, customers and artists providing content, so it is not just employees but a broader community that is painting the TRJ fence.

TRJ is now the leading CD retailer in Japan, the only country in the world where digital sales are not growing (they are actually in decline, from almost $1 billion in 2009 to just $400 million in 2015). And recognising that their customers love to collect hard, rather than just digital, copies of products and experiences, TRJ has teamed up with local record companies and artists to develop innovative ways of grouping these things. They were the first in the world to team up with artists to bundle concert tickets and backstage passes with music sales. They sell packages, like those of popular “girl group” AKB48, which combine CD purchases with club memberships, stickers, cards, posters and even rights to vote in AKB48 “elections”. They actively promote in-store concerts, signings and conversations with local acts and labels in a fiercely parochial market (in Japan, acts from overseas make up a paltry 11% of total music revenue). And they stay open till midnight every day.

TRJ also engaged a much more active diversification programme as the music industry evolved. Whereas Tower in the US carried on as if Napster, the world’s first digital music sharing platform, was just a passing fad, TRJ became a majority stakeholder in Napster Japan (although this was wound down in 2010). It has a subsidiary record label, which specialises in what the Japanese call “idol” performers, and with major corporations NTT DoCoMo and Seven & I Holdings now major shareholders in the company, they are well placed to respond to emerging opportunities and threats in communication technology.

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

-

You should be able to develop a list of strengths and capabilities for TRJ pretty quickly. But the challenge, as with most strategy development processes, is to reduce this long list to a shorter list of key strategic strengths/capabilities that an organisation can really focus its energies on building strategies around.

You should be able to get down to around three to four things that are Valuable, Rare and Inimitable and two to three Dynamic Capabilities (there may be some overlap between these) using the frameworks outlined in this chapter.

We won’t list what we think all of these are here, but one you should have on your list is something along the lines of “TRJ’s close relationship with its customers and ability to communicate with them”.

-

To take just that one Dynamic Capability (DC), we can say that this helps TRJ sense opportunities by having a good idea of how their customer community’s needs are evolving and how the organisation may want to evolve or transform to meet those needs. Ask yourself if Tower Records in the USA had such good communication with its customers in its final years and what the consequence of this was.

See if you can link the other DCs or VRIO strengths that you developed in your answer to question 1 to an ability to Sense, Seize and Transform the organisation. It would be a good idea to see if you can draw these things in some kind of diagrammatic form.

- When people look at the demise of Tower Records they tend to focus on what appear to be obvious causes. These could be drawn out of an ESTEMPLE analysis. For example:

Technological changes mean that there are more efficient forms of delivering music than those forms that Tower specialised in.

Economic changes have led to people not wanting to fork out the same amount of cash for vinyl, CDs or video formats.

Social changes mean that the way people consume and share music has changed.

Environmental concerns favour the sharing of music and video content digitally to reduce the production and consumption of non-biodegradable plastics.

Legal changes have enabled artists to put greater protections around the digital delivery of their intellectual property.

All of these forces might lead us to conclude that Tower were simply operating in a maturing industry and nothing they could have done would have saved them.

But then, how do we account for TRJ’s success? They faced the same environmental and industry forces? Why has it been different for them? How have they been able to mitigate the environmental threats outlined above, and even perhaps turn these threats into opportunities?

If you’ve done a good job in answering the first two questions, the answer to that should be obvious. It certainly has something to do with how TRJ recognised and nurtured their dynamic capabilities. And Tower Records in the USA became distracted and lost sight of what their real strategic strengths and capabilities were.

![]()

5-2 Taytos: Out of the Frying Pan …

Tayto’s Crisps have dominated the Irish savoury snack market for 40 years. Every week the Tayto Group produces and sells 8 million packets of potato crisps (chips) and snacks in a country with a population of fewer than 4 million people. This means that, on average, every Irish person consumes almost 100 packets a year.

However, Tayto’s position is now under threat. British company Walkers, backed by the muscle of its parent company Frito Lay and Frito Lay’s owner, the giant Pepsico Corporation, launched the UK’s most popular brand of crisps in the Republic of Ireland on 17 March 2000 (St. Patrick’s Day). According to Andrew Hartshorn, Walkers Brand Manager for Ireland, Walkers intends to capture a “substantial share of the [Irish] market quickly”. Indeed, Walkers appears to not only want to eat up market share, but to change the way Irish consumers see potato chips. While Tayto’s generally come in dinky 25-gram bags, replete with the skin shavings and blemishes of the potatoes they once were, Walkers is a crisp without blemish. They come with a minimal trace of vegetable oil in bigger servings with a modern foil bag decorated in the global Frito Lay format.

While Walkers is now backed by an American parent, Tayto has recently gone the other way, returning to Irish ownership after US firm TLC Beatrice sold it to the Irish drinks company Cantrell & Cochrane.

All of Ireland’s crisps were imported from the UK until Mr Joe Murphy from Donabate, County Dublin, founded the Tayto Company in 1954. Murphy’s biggest claim to fame was his invention of cheese and onion flavoured crisps (prior to this the only “flavouring” option was salt). Cheese and onion is now the top selling flavour in Ireland and in the UK, where Murphy’s innovation was quickly copied. Originally, Tayto’s were produced by hand using two sets of deep-fat fryers, but the company grew quickly, aided by the financial association with Beatrice, who first acquired a stake in the company in 1965. Factories were built in Rathmines, Harold’s Cross and Coolock, all in the Dublin area. Tayto now employs over 250 people and boasts a low staff turnover as testimony to the family atmosphere of the company.

Tayto’s supply and distribution chains go deep into the Irish fabric. It only uses Irish potatoes grown under contract by farmers with whom Tayto has been associated for many years, and it has developed an intricate distribution network. Tayto distributes its crisps through one of the largest direct van sales operations in the country, with 10 regional depots located through the country supporting a roving fleet of 35 Tayto’s vans. This provides a 99% domestic distribution level – a quite remarkable feat given the still rural nature of large parts of Ireland.

To further consolidate these channels, a central distribution hub was created in 1996 in Ballymount, Dublin. The centre is fully automated and contains 10 automated loading bays, with the capacity to hold in excess of 150,000 cartons of crisps. All types of outlets are serviced by this system: supermarket chains, pubs, newsagents, garage forecourts, off-licences and independent owner-operator stores, and Tayto guarantees that each customer receives fresh product through weekly service calls.

The result: almost every shop in Ireland – from the biggest supermarket to the smallest independent corner grocer and the most remote petrol station – prominently displays Tayto crisps, a big factor in a market where it is estimated that approximately half of all sales are impulse purchases. Finding an Irish person, or anybody with a connection to Ireland, who is unaware of the brand is a difficult task. Indeed, the way in which some Irish speak of Tayto crisps seems to indicate a kind of spiritual attachment. In a recent survey of brands, Tayto was rated the third biggest Irish brand and first in the grocery sector.

While Tayto holds a domestic market position enjoyed by few indigenous consumer brands (in 1999, it held 60% of Ireland’s crisp market, and the second highest selling brand, King Crisps, is also owned by Tayto), it has no official export business in an increasingly global savoury snack market. However, there are what could be called “independent initiatives” that bring Tayto crisps to the world. It is often claimed that there are more Irish living outside of Ireland than within, and packets of Tayto’s are regularly dispatched to Irish emigrants from friends and family at home. Martin McElroy, an Irishman now living in Philadelphia, has developed an agency that now orders over 100,000 bags of Tayto’s a week which he sells through local wholesalers. “It’s wonderful to see the reaction of all the Irish people here when they walk into a shop and there is a box of Tayto Cheese & Onion,” claims McElroy. “But the Americans are really developing a taste for them too. In fact I can see that Tayto will be regarded as the luxury import in the same way that many American products such as nachos are regarded at home [Ireland].” The crisps are retailing for $1 a pack, twice what they sell for in Irish stores.

Walkers can also trace its history back 50 years. As a local pork butcher in Leicester in the English Midlands, Walkers began producing crisps as a way of utilising staff and facilities in its small factory while meat was heavily rationed after World War II. It began to expand into other British regions around 20 years ago. In recent years, with the backing of its new parents and the help of a big marketing budget wisely spent, particularly on television advertisements featuring British soccer stars, it has become the UK’s second most powerful grocery brand after Coca-Cola. Walkers now boasts annual sales of well over £300m and a 65% share of the UK potato chip sector.

Walkers/Frito-Lay/Pepsico is taking the Irish launch of its products very seriously. It has given away more than a million free packets of crisps and made an Irish variation on its theme of soccer-star television advertisements starring Roy Keane, who was one of the highest paid Irish players in the English football league, Andrew Hartshorn explains that the huge marketing budget that Walkers is currently using to push its crisps in Ireland is a “long-term investment” – a strategy that is part of a bigger global picture. Success in Ireland, Europe’s fastest growing economy and Walkers’ first overseas target, will help the company to develop the knowledge, experience and confidence necessary to launch into other European countries.

Evidence from Northern Ireland does not bode well for Tayto. While the Tayto brand (owned by a different company in the North) is still well regarded, Walkers replaced it as the best-selling crisp in just three years. However, there are many cultural and business factors that make the Republic a different market – not least of which is the clout of the myriad smaller independent stores which still contribute a much higher percentage of sales than in Britain or America and with whom Tayto has long-standing relationships. Tayto’s Managing Director, Vincent O’Sullivan, believes that Tayto can compete against the might of the multinational threat: “We’re not going to give away market share to anyone,” insists O’Sullivan. “What [Walkers] are going to find out is that it’s a very competitive market with strong local brands.”

5-3 Mojo MDA: Sydney Chainsaw Massacre

Two of Australia’s best-known advertising agencies, Mojo and Monahan Dayman Adams (MDA), merged to form Mojo MDA. John Singleton, the well-known advertising man, described the merger as being akin to the Beatles combining with the post office.

Mojo’s offices were in Paddington, entry being via a long, narrow, paved driveway lined with ferns, which then opened out into a large courtyard with willow trees and a fernery. The offices surrounded this courtyard. Those on the ground floor opened onto the courtyard, while those on the upper level opened on to a wisteria-covered balcony that overlooked it. MDA’s offices were quite different, located in the concrete and glass high-rise area of north Sydney.

The agencies had also brought to the merger quite different staffing structures. Mojo’s practice was to employ mainly highly paid senior staff that were given a high level of independence. They operated with a flat organisational structure of few hierarchical levels. This arrangement has been described as being “like freelancing under the umbrella of a company with the bonus of the companionship of like minds”. MDA had a much more traditional pyramid structure of a few senior staff supported by large numbers spread over several hierarchical levels.

Mojo had a reputation for being undermanaged. For example, no one holding a position in the company had a clear job description specifying the duties and responsibilities for that position; there was no such thing as formal meetings, and the use of written memoranda was just not an acceptable practice. Some people, including many in Mojo, interpreted “undermanaged” to mean poorly managed. Consequently, one of the attractions of the merger with MDA for such people was that MDA had a reputation as a well-organised “professional” company. For MDA, the parallel attraction was the highly regarded skills of Mojo’s creative staff. Together they constituted the largest Australian-owned agency. Size was also a major consideration in the merger. Both agencies were proud of their independence from foreign ownership and wished to maintain this situation while also enlarging to a size where they felt they could successfully take on the advertising giants of New York and London.

Mojo MDA was building a new office at Cremorne which would house all its staff, but until that was completed it was decided that all creative staff (copywriters, art directors and production staff) would move to Paddington while all management staff (the “suits”) would be located at the north Sydney offices. One of the Mojo people required to move was its Finance Director, Mike Thorley, who moved to north Sydney where he was to work under Stan Bennett, MDA’s Finance Director, who had been put in charge of finance for Mojo MDA. He describes the situation and what followed.

Thorley was one of the original Mojo employees and, as such, did not really think of himself as an employee, more as a partner. That he was not a partner was brought home forcefully at the time of the merger. Like the rest of the staff he had no warning that Mojo was going to merge with MDA and was shocked and angered by the announcement.

Thorley was referred to as the shop steward of Mojo: he looked after the staff, moulded them into a team and was at least partly responsible for giving the agency its character. However, after the merger he was banished to north Sydney to work for Stan Bennett. He did not go quietly.

To try to make the Paddington people feel at home in north Sydney at MDA, management installed a bar so the staff could follow their usual custom of a few drinks after work. But it was a modern black laminate structure running around the edge of the room. It looked like some up-market suburban pub. It was nothing like the solid white bench in the kitchen at Paddington and it seemed to Thorley that it summed up the differences between the two agencies: it was a symbol of how Mojo had let its people down. In an act of defiance, he took a chainsaw to work one morning and cut the bar in two.

5-4 Channel 5 & the BBC: Competing with the New Kids on the Block

Channel 5, Britain’s newest terrestrial (non-cable) television channel, had a problem. Unlike its competitors, it did not have a clear identity. Consequently, viewers did not know what to expect from it and, subsequently, seemed less likely to tune in or build a relationship with it.

British researchers have recently demonstrated that viewers tend to have clear images in their minds about the identity of the television channels they watch. BBC1 was seen as staid and establishment, but reliable – “the Queen Victoria of channels”. BBC2 was seen as an “enthusiastic educator – something between an old professor and a trendy teacher, with a touch of social worker keen to save the world”. ITV was seen as jolly, lively and “more normal”, but also a bit “dodgy,” with something of a “used-car business” about it. Channel 4 was identified as a “Richard Branson” – entrepreneurial, dashing and risk-taking, often pushing the boat out a bit too far, but then this suited its character.

The researchers also found that people do not apply the same standards to each channel. For example, it appeared that one reason for making a customer complaint was if a programme delivered something at odds with the customer’s anticipations of the channel’s personality, thereby causing dissonance that led to the relationship between viewer and channel being questioned. A racy programme shown on Channel 4 would receive fewer complaints than the same programme shown on BBC1 – partly because of the profile of the people tuning in to each (those watching Channel 4 were likely to be people who had already decided that the station’s ethos was OK with them), but also because of viewer expectations. Using the same logic, when Channel 4 recently took over the rights to show cricket matches from the BBC, it knew that it would have to show them in a more dynamic, less traditional way – otherwise viewers would wonder “what on earth is happening to Channel 4?” The message seems to be that, as with the people in their everyday relationships, customers will tolerate difference between different companies far more than inconsistent behaviour from one company.

Channel 5’s problem in this regard is that their programming seems particularly inconsistent: an unruly mix of half-baked game shows, soft porn and 1960s wildlife programmes. It is hard to see any positive pattern to it and thus it is hard for any significant segment of the population to connect with it. This is partly due to circumstances beyond its control. It is young and it could be said that it is still finding its way – no infant arrives with a personality completely intact. Plus, just after a highly successful launch, when the Spice Girls were used as the channel’s spokespeople (indicating a bright, optimistic, youthful image), the five Spices became four, and those four seemed to go their own separate ways, making it difficult for Channel 5 to build on the initial success of the launch.

Eighteen months after the “personality research” described above came out, confusion still prevailed regarding what Five’s character should be. Channel 5 executives recently announced that the channel was going to reposition itself dramatically – moving away from its salacious programming to become a “family broadcaster emphasizing popular entertainment”. However, this did seem to have been compromised somewhat when one Channel 5 senior executive was reported to be demanding that his channel be allowed to show more explicit sex.

Channel 5 is not the only channel that is working on its personality. ITV has recently launched separate cable-only channels, with related but slightly different personalities, that will allow it to show a more diverse range of programming without compromising its flagship identity, and the BBC is reportedly not entirely happy about the staid Queen Victoria image. The BBC’s public service remit is to “serve all people” and, in response to what its own research defines as an increasingly fragmented and multicultural market with different delivery methods and more consumer choice, it is currently asking itself how BBC1, in particular, should change its personality to better match the new environment.

By the end of 2002, Channel 5 did seem to be beginning to establish an identity in the market. In the Independent Review, critic Thomas Sutcliffe wrote the following:

Evidence that even the most incorrigible miscreants can mend their ways was also available on Channel 5, which formally relaunched itself after months of stealthy self-improvement. The [garish] “Dolly Mixture” logo [around the number 5] has now gone to be replaced with a classy sans-serif text [of the word “five”]. Even more mind-bogglingly, it has been running a series of documentaries on ecclesiastical art and architecture [called Divine Designs], presented by a genial anorak called Paul Binski. It’s as if you were to go on an 18–30 holiday and find that the pool-side entertainment was a lecture on 14th-century choir-stall carving. On Tuesday night, Binski referred to the medieval church’s attitude to its congregation: “We’re actually sinful, vicious, oversexed, greedy, stupid creatures,” he said – a perfect summation, as it happens, of the world-view which appeared to govern Channel 5’s early schedules. Now [this appears to have] given way to a [blend] of the high minded and cheap and cheerful. Divine Designs is not finely wrought television. The final credits list just 13 people in total. In television terms, this is one man and a dog he’s borrowed for the day, but that hardly matters. Binski overflows with enthusiasm for his subject. Some medieval historians might have winced at the suggestion that church gargoyles were “the 14th-century equivalent of The Simpsons,” but it got the point across – and you won’t find such a conjunction anywhere else on television. The Channel 5 button on my remote control has remained in factory condition until now – I have a feeling it might be getting shinier.

Sutcliffe’s comments were typical of a number of other favourable reviews of the relaunch of Five.

In response to the emergence of new competitors getting their act together and better targeting younger demographic brackets, the BBC went through a period of flirting with cultural change, rebranding and taking on more innovative approaches to change its association with staid and stable values. It expanded its portfolio of channels (this now includes additional channels such as BBC3, BBC News 24, BBC Children’s, BBC History and a number of others) and has sought ways to appear more “youthful” and “relevant to young people”.

Postscript: since this case was written, and perhaps as a sign of the BBC recognising the absurdity of trying to put all its eggs in the basket of making its brand more “sexy”, a new comedy series created by the BBC called W1A (The BBC head office’s postcode) started screening in 2015. It was filmed in a “mockumentary” style and followed a series of farcical situations created by new managers and consultants seeking to replace the BBC’s culture that had made it so successful for the past 80 years with something more youthful and “fun”.

5-5 Hyundai: Striking a Chord?

It is likely that people personalise their relationship with their car more than with any other material possession. And automobile designers have been concerned with how potential customers perceive the “character” of their cars for many decades. Increasing competition in what is seen as a declining market has only intensified the focus on intangible factors like the perceived identity of car brands, and even new players from countries often thought of as simply focusing on low-cost products have become extremely sophisticated in these “arts”.

In keeping with the way that people anthropomorphise cars, Europe’s biggest selling auto magazine, Car, includes in its monthly review of all car brands a link to a band that, by analogy, seems to capture the identity of a particular brand, alongside the more normal performance measures and ratings. A selection of these brand/band relations are shown in Table 5.1 and related to changes in UK sales performance over the first part of 2009 relative to 2008.

At first glance, it does appear that those marques that have outperformed the industry average in a very tough year (where sales declined by 28%) are associated with bands that have also sold well, have made a successful comeback or have high visibility. It’s not so much that a brand needs to be associated with a “cool” band to do well. But it does appear that an association with musicians with a clear identity who are selling well to a particular market could be some indicator of success.

Take Hyundai as a case in point. This is the only brand to have increased sales in the UK during the period. Busted may not be at the cutting edge of musical excellence, or even particularly distinctive, but they seem to be fun and effectively shift product. And, like their stable-mates (Kia/Leona Lewis), they may appear bland and manufactured, but they seem harmless and are not without credibility, range and power. In fact, it may be that they are typical of what tends to go down well in this era.

Also doing well, relatively, were effective niche fillers like Suzuki (Madness), Ford (Kylie), Audi (Coldplay), Toyota (Daniel O’Donnell), and Jaguar (Tony Bennett). Mazda, like the Prodigy, do well by being on the edge of mainstream. In the middle, are MOR, or middle class, favourites like Dire Straits (Mercedes), ABBA (Volvo), Dido (Volkswagen), and Elton John (Vauxhall). Nissan, like Amy Winehouse, are a mixed bag. And Fiat (Paul Weller) too suffers from a lack of consistency.

Underperformers include the increasingly irrelevant Lexus/Kraftwerk; the random Mitsubishi/Utah Saints; and the “used to rock” Renault/Roxy Music and Subaru/Chilli Peppers. Bringing up the rear are American brands to which the UK authors of Car seem to delight in ascribing tragic musical doppelgangers.

But it may not be so clear cut – some brands have seen significant declines despite band analogies that would seem to be positive (Table 5.2). For example, BMW (Kanye West) and Porsche (Rolling Stones) saw sales decline significantly. Perhaps we should be cautious about seeing brand/band identity as an isolated performance indicator.

Table 5.2 UK new-car market sales SMMT analysis – January to May 2009 vs. 2008

| Marque | 2009 | % market share | % change | change relative to industry change of −28% | Band |

| Hyundai | 14,534 |

1.94 |

+8.00 |

36 |

Busted (bubblegum stuff, but not without cred) |

| Kia | 14,119 |

1.89 |

−7.36 |

20 |

Leona Lewis (characterless but gaining popularity fast) |

| Suzuki | 9,987 |

1.33 |

−16.97 |

11 |

Madness (a lot of fun) |

| Ford | 129,287 |

17.27 |

−17.48 |

10 |

Kylie Minogue (honorary Brit, hugely popular, great chassis) |

| Audi | 39,180 |

5.23 |

−19.41 |

8 |

Coldplay (slick, unstoppable, slightly annoying) |

| Toyota | 40,265 |

5.38 |

−20.20 |

8 |

Daniel O’Donnell (your Gran’s favourite) |

| Jaguar | 7,602 |

1.02 |

−20.29 |

8 |

Tony Christie (surprising us after years in wilderness) |

| Mazda | 17,646 |

2.36 |

−23.19 |

6 |

Prodigy (on the edge of mainstream) |

| Mercedes-Benz | 27,137 |

3.62 |

−23.63 |

6 |

Dire Straits (men of advancing years love them) |

| Volvo | 11,397 |

1.52 |

−23.73 |

6 |

ABBA (middle class, middle of the road) |

| Volkswagen | 62,892 |

8.40 |

−26.20 |

2 |

Dido (loved by the middle classes) |

| Nissan | 24,093 |

3.22 |

−26.64 |

1 |

Amy Winehouse (good range, but all over the place) |

| Vauxhall | 101,023 |

13.49 |

−29.46 |

−1 |

Elton John (decades of uncool, but still standing) |

| Honda | 31,423 |

4.20 |

−30.59 |

−2 |

David Bowie (keeps pushing new stuff but we want CRX back) |

| BMW | 34,098 |

4.55 |

−32.12 |

−4 |

Kanye West (brash, borderline genius) |

| Citroen | 25,788 |

3.44 |

−32.49 |

−4 |

Oasis (was massive; always threatening comeback) |

| Mini | 12,757 |

1.70 |

−32.42 |

−4 |

The Cheatles (a Beatles tribute act, of course) |

| Peugeot | 39,164 |

5.23 |

−33.52 |

−5 |

Tight Fit (as in The Lion Sleeps Tonight) |

| Porsche | 2,259 |

0.30 |

−33.24 |

−5 |

Rolling Stones (thoroughbred, bankable, cool, peerless) |

| Fiat | 17,197 |

2.30 |

−33.88 |

−6 |

Paul Weller (veers from highs like The Jam to Style Council lows) |

| Land Rover | 11,287 |

1.51 |

−40.37 |

−12 |

The Clash (utterly brilliant, but people spit at them) |

| Lexus | 3,115 |

0.42 |

−41.93 |

−14 |

Kraftwerk (highly technical, largely forgotten) |

| Saab | 4,517 |

0.60 |

−45.79 |

−17 |

Robbie Williams (no proper hits since 1990s) |

| Cadillac | 42 |

0.01 |

−46.15 |

−18 |

Garth Brooks (loved in America, ignored elsewhere) |

| Subaru | 1,265 |

0.17 |

−52.16 |

−24 |

Red Hot Chilli Peppers (used to rock, losing edge) |

| Renault | 21,139 |

2.82 |

−57.22 |

−29 |

Roxy Music (once at cutting edge, now plain & cosy) |

| Mitsubishi | 3,628 |

0.48 |

−61.32 |

−34 |

Utah Saints (marries tech with raw appeal and a random, sporadic back catalogue) |

| Dodge | 778 |

0.10 |

−65.94 |

−37 |

New Kids on the Block (unwelcome comeback tour underway) |

| Chrysler | 857 |

0.11 |

−75.43 |

−47 |

Bon Jovi (Living on a Prayer) |

| Total | 748,691 |

100.00 |

−27.89 |

Writing your own “resource-based advantage” case

Writing your own “resource-based advantage” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “The Mini Case” and “The Briefing Note,” guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and this is a good vehicle for that purpose. There are also a large number of websites that highlight interesting organisations that you might want to find out more about. For instance:

- Websites for national newspapers

- Forbes

- TechCrunch

- uk.businessinsider.com

- www.fastcompany.com

- www.huffingtonpost.com.

It is also worth noting that in the UK there is an excellent website for company information at Companies House. The address is https://beta.companieshouse .gov.uk/.

We find that writing a resource-based case works best if you can personally experience an organisation’s offerings. For instance, attending a show, visiting a hospital, entering a bank, buying a product, travelling on an airline; these experiences should help you to begin to question what the key resources and capabilities of an organisation are, even if they are not all directly apparent. You can begin to question what supports a great service offering or a reliable product and this helps give additional insight into more conventional means of organisational appraisal such as report and accounts.

![]()

Notes

- 1. Pascale, R. and Athos, A. (1981) The Art of Japanese Management, Warner.

- 2. Peters, T. J. and Waterman, R. H. (1982) In Search of Excellence; Lessons from America's Best-Run Companies, Harper & Row.

- 3. Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D. N. and Regner, P. (2017) Exploring Strategy, 11th edn, Pearson.

- 4. Collins, J. C. and Porras, J. I. (1994) Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies, HarperBusiness.

- 5. Angwin, D. N. (2007) Mergers and Acquisitions, John Wiley & Sons.

- 6. Hofstede, G. (1993) Cultural constraints in management theories, Academy of Management Executive, 7(1): 8–21.

- 7. Hankinson, G. and Cowking, P. (1996) The Reality of Global Brands, McGraw-Hill: 44.

- 8. de Mooij, M. (1997) Global Marketing and Advertising: Understanding Cultural Paradoxes, Sage: 189.

- 9. Porter, M. (1990a) The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Macmillan.

- 10. Hofstede, G. (1993) Cultural constraints in management theories, Academy of Management Executive, 7(1): 8–21; Smircich, L. (1983) Concepts of culture and organizational analysis, Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(3): 339–58.