8

New Ventures

If you’re not innovating you’re dying.

Mark Hipp, Vice President Enterprise Business Comm HP

Technology, sport and fashion have been combined to create a ground-breaking product for cyclists. The smart jacket, made by Google in partnership with Levi, is fashionable and technologically enhanced to enrich the cycling experience. It allows users to control their mobile phones and connect to a variety of services, such as music or maps. By swiping over the sleeve, users will be able to dismiss phone calls, double tap to get directions by accessing Google Maps, swipe up to get directions and down to change music. It will work with Google products and third-party services like Spotify and Strava, and more apps will be added in the future. This makes it attractive for other types of activities that value tracking, such as trekking and running. Flexible fashion-tech could have wide applications including sport, fashion and health. How has this product become possible?

The technology is the creative work of Google’s Project Jacquard, a division of the company’s Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP) Group. Conductive fibres are woven directly into the clothing so that motions made over the sleeve register as touch inputs, just like a touch sensitive screen. These are then sent via Bluetooth, an attachment on the cufflink, to your smartphone. The fibres are flexible allowing the garment to be washed, and for the jacket to stretch and compress, both of which are important for cycling. Wearable tech promises to revolutionise the clothing industry as it paves the way for clothes that can monitor health, even remotely, for real time health care, display moods through changing colours and designs, and facilitate lifestyle through network communications.

But how do new ventures such as Project Jacquard, that are innovative, entrepreneurial and add strategic value, come about? Why does innovation happen more often in some organisations than others? And if organisations do not see opportunities to innovate internally, are there alternative external ways in which they might engage with partners or acquire new ventures?

There has been increasing interest in finding the answers to these questions and this has seen the rise of three sub-fields in strategic management: innovation, entrepreneurship and mergers and acquisitions (M&A). It is important, however, when thinking strategically about these fields to see the connections between them. For example, innovation only adds strategic value if an entrepreneurial spirit can figure out how to bring it to market or to citizens who will appreciate the value it provides. And entrepreneurship only adds strategic value if it promotes an innovative product, service or experience that people want. Successful M&A that creates strategic value – or helps an organisation to win – also increasingly requires a focus on innovative approaches and entrepreneurial understanding.

In this chapter, we will explore innovation and entrepreneurship and the incubators that are designed to enable these new venture-promoting activities both within existing organisations and outside of them. Then we will examine how organisations can look externally for the new ventures that will help them advance: either through joint ventures (like that between Google and Levi described above) or through M&A.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship

Incubators and accelerators

Innovation is increasingly seen to be a big deal for organisations and countries alike. China, Singapore, New Zealand, Argentina, the USA and Britain, to name only a few, are all seeking to promote innovation and entrepreneurship. China’s “Made In China 2025” initiative seeks to move China from being regarded as a copier of technology from abroad to one of the world’s leading producers of patents and innovation. Singapore has built a new university devoted to the teaching of, and research in, design and technology as it seeks to accelerate toward higher-end innovation. New Zealand and Argentina are among many nations for whom primary industries have dominated their GDP that are now seeking to “move up the value chain”. Regional and national programmes in the USA aim to consolidate their position as the premier home of innovation, while programmes in Britain seek to define and promote a particular brand of design typical for that country.

Perhaps the most material sign of this increasing national interest is the rise of “incubators” and “accelerators”: spaces that provide (often subsidised) room for entrepreneurs to innovate, work, be mentored, collaborate and grow. All over the world, from disused railway stations in Paris, to whole streets like InnoWay in Beijing, disused buildings from the industrial age are being turned into retro-chic spaces for the new ventures that will reflect the 21st century. Accelerators, which seek to help start-ups move quickly to establish their ideas in the market (e.g. Y Combinator, Techstars and the Brandery) and incubators, which provide a helping hand to individuals and small groups seeking to get started (e.g. Idealab, Impact Hub and BizDojo), are just some of the many brands moving into this arena, with varying degrees of assistance from governments around the world, and exploring them on the internet can be a gateway to a whole new world of business.

Frameworks for thinking strategically about innovation

With the increased interest in innovation, there are now dozens of frameworks available for helping you to understand different kinds of innovation. We outline three below: Keeley et al.’s Ten Types of Innovation; Sawhney, Wolcott and Arroniz’s Innovation Radar and Bilton and Cummings’ Six Degrees of Strategic Innovation.

In the book Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs, Larry Keeley and his co-authors argue that not all innovations are the same.1 They outline a range of different archetypes related to the “configuration” of an innovation, the nature of the whole “offering” and how the user’s “experience” of the innovation can be enhanced. We describe the Configurational and Experiential forms of innovation below, but you can search out the full list, if you are interested, on the internet.

Configuration Innovations

- Profit Model Innovation: Could you use bundled or flexible pricing, advertising revenue, membership, metered or subscription models to earn money in innovative ways? For example, HP loses money on printers, but makes money on ink.

- Network Innovation: Could you work with new or unique partners and suppliers to create and deliver value? New developments in “Open innovation”, or innovation that involves customers and other external stakeholders, are good examples of this. Check out how LEGO’s “Ideas” and “Cuuso” websites enable fans to bring good ideas to LEGO and on to market.

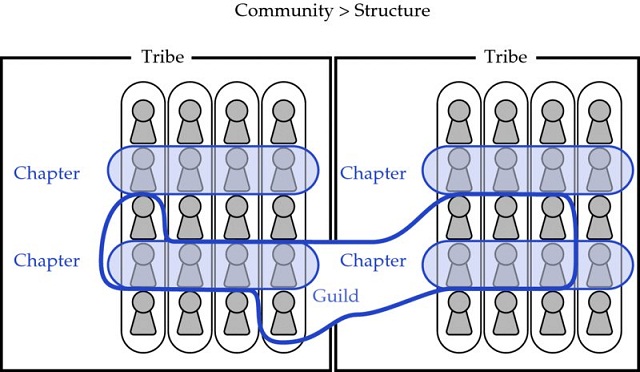

- Structure Innovation: Innovating how you organise and align your organisation, talent and assets to create more value. For instance, believing that community is more important than structure, Spotify organises people into guilds and teams rather than departments (see Figure 8.1).

- Process Innovation: Innovating with a new production process. Zara’s famous emphasis on fast manufacturing delivers from sketchpad to shop floor in three weeks.

Figure 8.1 Spotify’s innovative organisation – tribes, chapters and guilds

Experience Innovations

- Service Innovation: Innovating by adding value in how you support customers find, buy, pay, enjoy and dispose of your product. The Jersey Post example from case 8.5 offers service innovation for a mature product in an unexpected way.

- Channel Innovation: Innovating how you deliver your offerings to customers and users. Hey Juice, in Live Case 6-4, provides a good example of this.

- Brand Innovation: Innovating how you present your offerings and business in a distinctive, memorable and likeable way. For example, Virgin seeks to brand products and services distinctively by injecting a dose of fun.

- Customer Engagement Innovation: Innovating how you foster compelling interactions. Blizzard’s World of Warcraft is an online role-playing game that succeeds by fostering collaboration and community between players.

The Innovation Radar is a spidergram that helps focus on how innovations will add value.2 It is arranged around its four compass points: What is the offering? Who is it for? Where will it be delivered? How will the processes that will deliver it work? (See Figure 8.2.) The heuristic was developed by Kellogg School of Management researchers Mohan Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz and can help highlight how, for example, new platforms and solutions must be mindful of what the new value being advanced is and who is going to benefit. Thinking through an innovation by going around the spidergram’s four points and eight dimensions (the lines between the compass points) and analysing how each can be pushed to create a greater overall area of strategic value can be very useful.

Figure 8.2 The Innovation Radar

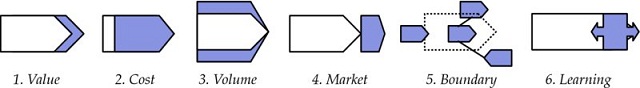

Another approach, which focuses specifically on thinking through whether an innovation is likely to create strategic value rather than just being a creative idea, is Bilton and Cummings’ Six Degrees of Strategic Innovation from their book Creative Strategy.3 While a lot of emphasis is now placed on organisations being creative, often this does not result in improvements to an organisation’s strategy. A good way to effectively join creativity to strategy, Bilton and Cummings argue, is to creatively redraw the shape of the generic value chain. Their research identified six main archetypes of innovating seen through this lens (see Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Six Degrees of Strategic Innovation

(Source: Bilton and Cummings, 2010)

The first and most obvious degree is value innovation, where products or services perceived to have greater value to a market are invented or extended. Value innovation does not need to be a grand invention, like the light-bulb or iPad, as small additions to a value proposition can have major effects. Sony’s Walkman shifted the value chain in their industry in the 1980s by adding portable to music.

Momofuku Ando was named Japan’s inventor of the 20th century. He added instant to noodles. While he didn’t invent a new product, his was a highly significant value innovation when one considers that 86 billion servings of instant noodles are consumed each year.

Indeed, asking what adjective or verb you should be putting ahead of your product or service can be a very good way to inspire strategic innovation in an organisation. Progressive, a large US insurance company, completely reorganised its business model around a revised view of the value they provided to customers: it wasn’t insurance, it was speed; in other words, providing customers with insurance quickly, so that they could get on with other things.

The second degree, cost innovation, seeks to increase margins by the creative reduction of costs. Recent examples include the fashion companies that recognised that putting on full-blown catwalk shows during a recession was not good for their image; they developed online viewing opportunities, saved money and benefited from enhanced viewer feedback. Other organisations, such as Tata and One Laptop Per Child, have completely changed the view of how much a car or a laptop could cost by setting audacious targets and reengineering traditional processes from the ground up.

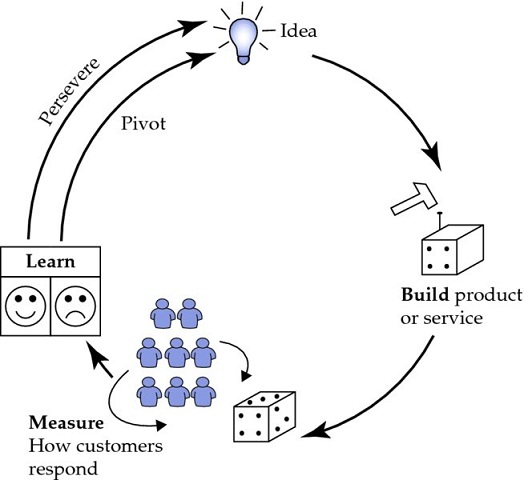

A range of methodologies for helping organisations and independent entrepreneurs to bear cost-saving efficiencies in mind when innovating, such as Lean Start Up Methodology, Lean Manufacturing and MVP (or Minimum Viable Product) frameworks can be grouped under the heading of Cost Innovations. These frameworks are generally presented as circles or spirals reminiscent of the Total Quality Management circles developed in Japan in the 1980s where firms like Toyota sought to improve quality and functionality while reducing costs. The aim with these models is to encourage quick and cost-efficient prototyping, learning and pivoting based on feedback, and therefore to eliminate as much waste and bureaucracy as possible.4

The third degree, volume innovation, is about creating ways to get more into or out of the throughput of a standard value chain. A classic example is Henry Ford’s combination of the conveyor production line system and doubling worker’s pay to enable the company to run around the clock work-shifts so they could meet surging demand for the Model T.

The fourth degree is market innovation, which is about devising new ways of relating to the market by focusing on innovative means of delivering or experiencing the product (see Figure 8.4). Elias Howe invented the mechanical sewing machine but quickly went under because of his insistence on selling them at full price. Isaac Singer recognised that the productivity benefits of the new machines were difficult for factory owners to fathom. So he gave them away and charged rent for them. Very few people today have heard of Elias Howe. In the music industry, bands like Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails changed the way consumers related to music by giving away free downloads, inviting customers to remix and upload their own versions of songs, and generating revenues from concert tickets, customised services and special events instead of relying on declining music sales revenue.

Figure 8.4 The Build, Measure, Learn approach for cost-effective innovation

Boundary innovation is about finding ways to break down traditional boundaries between sectors, or customers or suppliers and an organisation, and consequently breaking up and reconfiguring the value chain. The concept of crowdsourcing, where organisations put out a call for potential solutions and award prizes or contracts to the winning entries, is a good example of blurring the boundary between the design department within the firm and other stakeholders traditionally seen as outside.

The sixth and final degree of strategic innovation is learning innovation: figuring out how the organisation can learn better about its capabilities and its potential customers. LEGO Ideas and LEGO Cuuso, mentioned above as a Network Innovation, achieve both learning and boundary innovation by bringing fresh ideas from outside of the organisation in and helping the organisation learn about the behaviour and likes of its customers.

Entrepreneurship

Bilton and Cummings’ book moves from the importance of thinking strategically about innovation to the importance of good entrepreneurship in advancing strategic new ventures. They argued that there are now thousands of books written on innovation and nearly as many on entrepreneurship, but often what falls between these two growing pillars of knowledge is the interdependency between the two. They propose the following “law”:

The force of a creative strategy = innovative mass x entrepreneurial acceleration.

A good illustration of this “law” in action can be seen by contrasting the careers of Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison. While Tesla was at least as good an innovator as Edison (many would say he was superior), Edison had far more impact on business and society because he and the team he built around him always had one eye on the market and its needs. In other words, Edison was far more entrepreneurial: he and his team could recognise how an innovation could be matched with a market opportunity, or, if it couldn’t, how it might be adapted in order to.

Entrepreneurs tend to fall into two camps as to how they go about recognising such opportunities, and there are two theoretical approaches that reflect this (see Figure 8.5). The first sees the entrepreneurial spirit as more scientific, diligently seeking to uncover the new ideas and opportunities that exist in the world and acting on these ideas after calculating the risks; the other sees entrepreneurship as a more creative enterprise, with the entrepreneur being more of a free-floating artist or dilettante using their mind and networks to create ideas and opportunities and relying on their vision and self-belief to give them the confidence to chart the uncertain waters of getting the business off the ground.

Figure 8.5 Central assumptions of discovery and creation theories of entrepreneurial action

(Source: adapted from Alvarez and Barney, 2007)

However opportunities to bring an idea to fruition are recognised and assessed, there are a number of important steps that entrepreneurs generally follow to make the most of what must, to some degree, be a leap of faith in the idea. Bilton and Cummings explain these in relation to the Capoeira diagram in Figure 8.6.

Figure 8.6 Five phases of entrepreneurship

(Source: adapted from Bilton and Cummings, 2010)

The Recognition phase is about creating or discovering good ideas matched with market opportunities. The Development phase is about supporting (either personally or with the support of useful networks) and exploring the idea. Evaluation means testing the idea, judging potential, directing the idea to market or back to the drawing board. Elaboration is about fixing on the idea, boundary-setting and matching it to distribution channels. The final Launch phase is about delivering the idea, and recognising the potential for learning and reinvention, as expressed in those innovation frameworks we discussed earlier in the chapter.

Encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship in organisations

While the view of the lone entrepreneur working in their garage has captured the imagination when considering where innovation comes from, a great deal of innovation is achieved through organisational processes for creating new ventures.

For example, companies such as 3M recognise well the benefits of stimulating this type of behaviour: they have proof! One of its most famous products, the Post-it note, originated through “experimentation and failure”. An employee was tasked to develop a new adhesive but failed in the attempt, producing a glue that failed to stick properly. Fortunately for 3M, rather than rejecting the product, the commercial possibilities of “faulty adhesive” were perceived as this employee took the idea to others in the company and the Post-it note was born, soon turning into a multi-million-dollar product for the company. 3M now encourages its employees by giving them time to experiment and creating a culture that promotes innovation and does not penalise failure.

This type of culture, where innovation and entrepreneurship in employees are encouraged by rewarding these behaviours with financial incentives, recognition, time allowances and other benefits, is becoming more common among large businesses (and we shall look at more examples soon), but it is still not the norm.

The reason many large companies struggle to innovate is that they have developed robust structures, engrained behaviours and patterns of activities and routines that underpin current performance, but which are very resistant to change and thinking differently. This problem beset Kodak as the digital camera took off. Although the growth in the digital camera market was clear, Kodak failed to invest significantly in extending their capabilities, even though they had invented the product, as they continued to make significant profits from their traditional photo film business. The “corporate immune system” of downplaying or rejecting new initiatives led to Kodak’s downward spiral, with failure to invest in and market the new technology while continuing to promote declining photo film.

Recognising this problem (and seeking to avoid it), some large successful companies physically separate new ventures from the main business. A popular term for these internal but separate departments is “Skunk Works”. The term comes from Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Development Programs unit that developed many famous aircraft such as the Stealth Bomber.

Many companies have followed Lockheed in recognising that for real innovation to occur, employees need physical and psychological space to be creative in, where the usual controls and norms of an organisation do not apply. For example, The Prudential created a new business unit called Silicon Warf where employees could think and act differently and where failures were tolerated more than in the main financial business. They created the first internet bank, egg.

Other examples include Google’s secret lab Google X, which works on “shoot for the stars” type ideas like space elevators, indoor mapping systems, self-driving cars and wearable computers. And at Apple, design guru Jony Ive and a dozen hand-picked designers have a secret lab working on “material that the world is not quite ready for”.

While Silicon Valley companies might be expected to have Skunk Works, some traditional manufacturing companies also have highly successful innovation centres. For instance, DuPont has one of the world’s oldest industrial research laboratories, in Delaware. It is famous for inventing nylon, kevlar and neoprene. Today it is at the forefront of research on industrial biotechnology and advanced agriculture. And Nordstrom has an Innovation Lab that uses Lean Start-up and Design Thinking to create disruptive ideas that can be brought to market in a matter of weeks. Toyota too has a famous entrepreneurial and meritocratic process whereby anybody from a senior executive to a factory worker can promote and seek sponsorship for innovative ideas.

Even universities, often seen as the most traditional and staid institutions, are rapidly increasing their investment in incubators, such as Lancaster University’s Enterprise Centre, and science parks, such as Oxford University Science Park, to help develop and commercialise new ideas from academics, often in partnership with the private sector.

External New Ventures

Sometimes it is not feasible for an organisation to innovate internally. It may be far too expensive, it may be too risky, it could be too slow in a fast-moving industry and the organisation may not have the right, or sufficient, innovative capabilities and resources. For these reasons, an organisation may look externally for new ventures. There are two major ways in which these can be engaged: strategic alliances (sometimes referred to as joint ventures or JVs) and mergers and acquisitions (M&A). In strategic alliances, the organisations involved remain distinct entities, whereas in M&A they are combined.

Strategic alliances

Strategic alliances allow companies to access partner resources and capabilities in order to pursue common goals. The idea is that partners create a win-win strategy through reciprocal arrangements. This can be quicker and cheaper than gaining access to resources and capabilities through acquisition and also allows market risks to be shared.

Strategic alliances can be used to create new products and services, particularly when partners’ complementary strengths can be combined (as in the Google and Levi example at the head of this chapter). They can also be used to achieve scale advantages through combining inputs, products and services and may allow access to new markets where one partner may have products or services to sell and the other partner is a local distributer.

There are two main types of strategic alliance: equity and non-equity; and these can be either bi-lateral (between two parties) or consortium alliances (multi-party networks).

- In equity alliances, partners create a new entity. The most common form is the joint venture (JV), where the two or more organisations involved remain independent but they create a new jointly owned organisation. Equity alliances of more than two partners may be termed consortium alliances, and well-known examples exist in the airline industry such as the Star Alliance and One World networks of airlines.

- Non-equity alliances tend to be based on contracts. In some industries (such as automotive) these may involve long-term supply arrangements. Franchising is a non-equity based alliance where one organisation gives another the rights to produce the franchisor’s products or services. This model has been used extensively by fast food chains to grow rapidly with limited capital investment, and was a very effective method for McDonald’s to expand internationally. Licensing similarly allows partners to use intellectual property such as patents or brands in return for a fee.

Strategic alliances have many advantages; costs and risks are shared and they are relatively quick and easy to enter into and exit from. However, they do have their weaknesses and limitations:

- The governance structure is often volatile as decisions need to be shared.

- There may be cultural differences and also concerns about the loss of trade or technology to partners.

- Partners generally operate in different contexts that may change, influencing partner enthusiasm and capacity for the relationship. Strategic alliances therefore are fluid in nature, and as they evolve, tensions between partners may result, causing mutual trust to deteriorate.

- They can be regarded as collusive, where the partners seek to increase market power in cartel arrangements. These will increase their bargaining power over customers and lower prices from suppliers, and in many countries regulators will act to prevent these arrangements.

Because of these and other issues, reported failure rates for alliances or JVs are high at around 70%. Many reasons are cited including selecting the wrong partner, overly optimistic expectations, lukewarm commitment, poor communication, poorly defined roles, unclear value creation, loose agreement, little relationship building, a weak business plan, lack of alliance experience and not bridging partners’ styles. An example of this kind of breakdown was the termination of the joint venture between Indian retailer Bharti Enterprises and US giant Walmart, to build and operate cash and carry stores in India, after seven years of operation.

Strategic alliances therefore require sophisticated interpersonal, communication and negotiating skills in order to deal with potential and real conflicts. To manage JVs successfully, the following elements deserve close consideration:

- Strategic fit: The joint venture partners agree to pool some of their resources and capabilities in order to reach strategic goals that they could not obtain otherwise on their own. Therefore it is important that the long-term objectives of the partners are compatible.

- Capabilities fit: It is important that each partner is willing and able to contribute the resources and capabilities needed to make the joint venture a success. At the outset, it is important to identify potential gaps that must be filled to achieve the JV’s potential and the actions that will be taken by the partners to fill them.

- Cultural fit: Cultural differences can exist on different levels, such as national, ethnic, regional, industry or company, and these can all influence the success of a JV. In particular, they may influence business priorities, objectives and timing, approaches to competition, how the JV should be controlled and how it should be managed.

- Organisation fit: How each partner can influence the way in which a JV operates is crucial to its longevity. It is important to establish how decisions will be made, what controls will operate, what standards will be set and how disputes will be dealt with. This means parties will need to be willing to compromise.

- Communication fit: Ongoing communications are vital for JV success in order to provide the mechanism for discussion of new ideas, growing concerns and for resolving any problems. Effective communication channels must therefore be in place.

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A)

There are many motives5 for engaging in mergers and acquisitions, but there are four main strategic reasons for using M&A in order to create new ventures:

- Acquiring new resources: Here the acquirer purchases a company for unique and valuable resources such as brands, products, technology, physical property (such as mineral rights and real estate) and intellectual property rights. The acquirer may not be able to create brands and products internally, so acquisition may be the only alternative if these are deemed strategically necessary. These new resources may add value to the acquirer who may be able to sell more of the new resources through its own distribution system, or combine them with their own resources to create value. For instance, Nestle acquired Rowntrees, a UK chocolate company, so it could sell its branded products, such as KitKat, more effectively worldwide.

- Acquiring new markets: To enter a new region, an acquirer may purchase a company that is in a different geographic market. This would help overcome entry barriers that could include cultural differences, regulatory restrictions, political interests as well as industry-specific barriers such as controlled distribution and supply chains and competitor backlash. One reason why HSBC bank has made many acquisitions in different countries around the world is in order to create synergies from building a global bank and to control regional risk variation.

- Acquiring new capabilities: Acquirers may not have the capabilities they need to create certain new products, enter new markets or the management talent necessary to achieve a strategic reorientation of the acquirer. In some high-tech industries, the rate of innovation is faster than the rate at which the acquirer can innovate. This has led Cisco Systems and Alphabet to acquire lots of innovative start-ups in order to gain innovative capabilities and to then commercialise and distribute the resulting products and services.

- Acquiring the future: Sometimes organisations sense that different technologies are converging, such as watches and computers, or clothes and technology. In these instances, they may acquire in a different technology area in the hope that a new industry might be created in that emerging “boundary” space. For instance, Google acquired an optics company on the basis that personal computing could be worn and viewed through glasses.

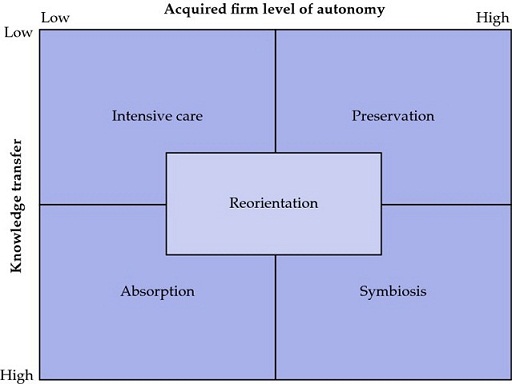

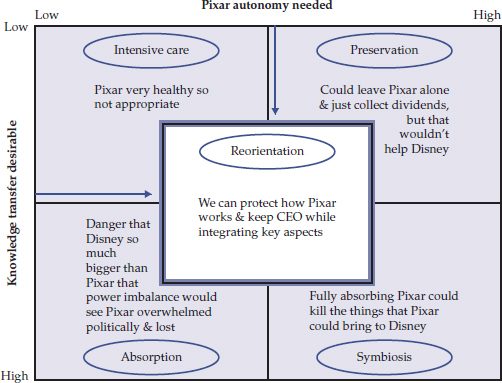

Although acquiring a company may seem to be the most difficult and important thing in an M&A process, the value from M&A is created after a deal is made. Hence, effective post-acquisition management, although often under-appreciated, is the key strategically.6 It is crucial to consider in advance how an acquisition will be integrated into the parent company if new opportunities can be created and synergies realised. For this reason, acquirers should have a clear view of whether the acquired company can and should be fully integrated into the parent or whether it should be “stand-alone” to some degree. The Post-Acquisition Integration Matrix, developed by Angwin and Meadows, can help evaluate the best approach (see Figure 8.7).7

Figure 8.7 Post-Acquisition Integration Matrix

(Source: Angwin and Meadows, 2015)

For new ventures to bring innovation to the parent, in most cases it is advisable to allow the acquired organisation’s key area of capability to remain as independent as possible. It needs to be given a high degree of freedom to make its own strategic decisions about capital investment, hiring and firing, development and marketing. Also, it needs to be free of capabilities and resources being imposed by the parent as these will arrive with conditions that may distort how the acquired company may operate. This approach can be described as “Preservation”. In this type of acquisition the acquirer can learn from the acquired company about how it achieves success in its markets gradually, over time.

If the strategic purpose of the acquisition is for the acquired company and the acquirer to work together to create something new, then it will be necessary for capabilities and resources to be shared between the companies and for managers to work together in order to think and operate differently from before. This is a “Symbiosis” approach. It is possible that the new way of organising that emerges from this symbiosis can replace the structures of the two original companies over time.

A further strategy that allows the acquirer to integrate administrative and outward facing operations of the acquired company, such as the marketing function and/or supply chain, while leaving the distinctive operations and research functions unaltered, can be described as “Reorientation”. Here the parent can redirect the acquired company’s products and services to other markets or market them to greater effect, and may also be able to reduce the costs of inputs to the company.

The other two main integration strategies are not recommended if the aim is to gain new ventures as they generally do not result in the creation of anything new. “Intensive Care” is generally employed when the acquired company is in poor financial health. The strategy is normally to buy this sort of business cheaply and then improve its financial condition (or wait for market conditions to change) before selling it off at a profit. And “Absorption” is used when the purpose of the acquisition is to integrate all aspects of the acquired company into the parent business. This means that there are high degrees of overlap between the businesses that serve to improve the strength of existing activities and reduce costs, often through economies of scale and scope. Absorption generally results in the routines and processes of the parent company dominating, and it is therefore often the case that innovative and distinctive characteristics of the acquired company are lost.

It is well reported that at least 50% of M&A fail. There are many explanations for this, but one critical aspect is that the overall strategy for the acquisition must fit with the subsequent integration strategy. Beyond making a good integration strategy choice, successful post-acquisition integration generally depends upon the same critical factors outlined above for JVs, namely strategic, capabilities, cultural and organisational and communicational fit (see Angwin et al. 2016). Even with those characteristics fully thought through, there is also an important need for the M&A process to be clear on how all critical success factors of the deal are linked up throughout the entire process.8 So, for instance, if the strategy behind the acquisition is to gain a new technological product and set of capabilities from an acquired company, it will be critical to ensure that the processes are in place that enable those to be protected throughout the integration process.

The Best Approach to New Ventures? It’s About Strategic Choices …

Changing macro, industry and competitive environments mean that organisations must innovate to maintain their strategic advantage(s). New ventures can be achieved through different methods of internal and external renewal. Each has advantages and disadvantages and so needs to fit the strategic and contextual situations of all the parties involved.

Internal new ventures, where innovative and entrepreneurial practices are sponsored within an organisation, build an organisation’s own capabilities but rely on significant commitment of capital and time. The advantages of this approach include adding to the stock of knowledge and building a commitment in the organisation as a whole with dedicated teams. It is not dependent on the use of other partners that may cause restrictions and compromises, it avoids cultural tensions with partners, and it allows the financing of the new venture to be spread over the life of the project.

However, there are also limitations: internal new ventures can be slow to yield results, expensive and risky in terms of resources and the reputation of the firms. If a new innovation doesn’t work, it probably can’t be sold off, and failure may be demoralising and damage the brand: there is nobody else to blame! Also, it is not easy to use existing capabilities as the platform for major leaps in innovation. If you believe that these weaknesses outweigh the strengths of internal innovation and entrepreneurship in your organisation, or the one you are analysing, then it may a better strategic choice to create new ventures by looking externally.

External new ventures have advantages over internal alternatives as they can be set up and produce results more quickly. In both strategic alliances and M&As, failure or breakdown will likely lead to losses, but these are less than those incurred in internal new ventures.

Strategic alliances are relatively cheap to create and can be targeted to specific projects. They can be tailored to particular resources and capabilities held by the partners. The costs and risks can be shared among the alliance partners, and they can be relatively easy and inexpensive to exit from. However, they are difficult to maintain as things evolve and the spoils must be shared.

New ventures born from M&A activity can be much more expensive as they generally involve purchasing entire organisations, many elements of which may not combine easily with the acquirer’s innovator capabilities. However, through ownership, innovative gains can be made in terms of revenue and capability increases and they are solely held and re-invested by the parent.

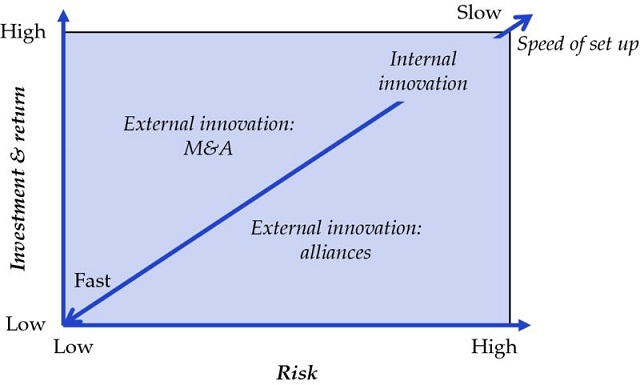

There may not be one best way to innovate strategically, but it is increasingly untenable for organisations to not innovate at all. The right choice is the one that best helps you to win, to achieve your strategic purpose. The only wrong choice is to do nothing. Figure 8.8 may help you assess the benefits and the risks and make your choices: Internal? External alliances? External acquisitions? A combination? With Jacquard, Google and Levis opted for an alliance. Do you think they did the right thing?

Figure 8.8 A Strategic Innovation Investment, Risk and Return Matrix

New Ventures Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

8-1 Pixar and Marvel: Ka-powing Disney

Analysts were highly critical of Disney’s $7.4bn acquisition of Marvel in 2009. However, in 2012 a single film “ka-powed” all others with $1.5bn (€1.12bn, £0.9bn) global ticket sales, becoming the third-highest grossing title of all time. The Avengers, from Disney’s Marvel unit, stormed the box office, bringing Iron Man, The Incredible Hulk, Thor and other Marvel super heroes together. Its success largely overturned analysts’ criticisms of Disney’s price paid for Marvel as an overpayment.

On paper, the acquisition looked a perfect fit. Disney was rethinking its entire approach to film-making in response to a contracting home entertainment market and falling DVD sales as every studio in Hollywood was under pressure to cut costs. Ready to move to a franchise-led strategy, producing films and brands that could generate sequels and spin-offs, Disney acquired Pixar in 2006. Not long after the successful acquisition and integration of Pixar, Disney started to eye up other growth ventures. Marvel, a brand that could deliver movies with stories that appealed to teenage boys – a demographic Disney (and Pixar) had found elusive – seemed like a good target.

The acquisition was not only about movies. Disney planned to use Marvel’s vast library of super hero characters throughout its business, from theme parks to television shows and consumer products, adding Incredible Hulk underpants and Iron Man lunch boxes to Disney’s staple inventory of Mickey Mouse merchandise. In addition, the deal retained Marvel’s CEO, Isaac “Ike” Perlmutter. His hard driving approach to gain a “big bang for each buck” appealed to Disney: “Marvel could make a great looking movie for a fraction of the price of a Jerry Bruckheimer (Pirates of the Caribbean producer) movie.”

However, the deal also added dramatic tension to the family-oriented company based in Burbank, California – largely, it appears, because of Ike’s management style. As Marvel’s largest shareholder before Disney, he took much of his $1.5bn payment in Disney shares, giving him a seat at the decision-making table. Since then he has become a force within Disney. He is a skilled cost cutter and has been described as obsessive about saving money. “He used to do this thing in our office that people would laugh at. If there was some used paper lying around he would rip it into eight pieces and would have a new memo pad.”

But Ike’s strong opinions and cost-cutting capabilities often put him at odds with colleagues. His interest in merchandising and toy licensing has shaken things up throughout Disney’s consumer products division (DCP) – one of Disney’s smaller divisions but accounting for 10% of all group profits (2011). The head of DCP had repeated conflicts with Ike over the direction of the division and left in 2012 along with the heads of communications, publishing, HR, Disney stores and the toys business. Three female executives hired a lawyer to seek individual financial settlements and another filed an internal complaint alleging Ike threatened her. DCP has now been re-organised around Disney’s big TV and film franchises rather than individual product categories.

The box office and commercial successes Marvel has produced for Disney have won Ike admirers inside and outside the group. With sequels to Thor, Captain America and The Avengers in the works, analysts are now speaking about the upside of the deal. But some former Disney employees warn of culture collisions and in-fighting ahead. You would think that Disney, with all its heritage and culture, would prevail, but with the swagger in former Marvel employees’ step following the success of “their” movies, the common question in the hallways [at DCP] was: “remind me who bought who here?”

Sources: Financial Times 1 & 4 Sept 2009, 7 Sept 2011, 13 July and 8 Aug 2012

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

Disney acquired Pixar and Marvel because these companies had established capabilities, characters and fan-bases that would have been time-consuming and extremely difficult for Disney to develop in-house and innovation with respect to new characters and story-lines can be very “hit and miss”. Furthermore, Disney would have been forced to compete with these brands, with their own movies and characters, if they hadn’t acquired them and wanted to grow. And, if Disney hadn’t acquired them, it is likely that one of their large competitors would have.

We developed this customised version of the Post-Acquisition Matrix to illustrate Disney’s re-orientation approach to the acquisition of Pixar. It ought to be clear that a similar non-obtrusive approach should be taken as a post-acquisition strategy with Marvel.

However, whereas Disney has nurtured Pixar, and Pixar has, in turn, behaved like a “good child”, Marvel is showing signs of being more of a tempestuous teenager. Perhaps Disney will need to adopt more of a hands-off or Preservation approach, at least initially, with Marvel, as trust between the two entities and their employees is established. What post-acquisition strategy would you follow to maximise the returns and minimise the risks?

![]()

8-2 Ofo: China’s Uber for Bicycles

Recently, a Harvard Business Review article titled “Why Can’t China Innovate” explored the perception that China “doesn’t do innovation”: “The Chinese invented gunpowder, the compass, the waterwheel, paper money, long-distance banking, the civil service, and merit promotion” it began, and “until the early 19th century, China’s economy was more open and market driven than the economies of Europe.” But, the authors explained, today most “believe that the West is home to creative business thinkers and innovators, and that China is largely a land of rule-bound rote learners – a place where R&D is diligently pursued but breakthroughs are rare”.

The article outlined a number of suggested reasons for this:

- The fact that most Chinese start-ups are founded by engineers, not designers or artists

- The scale of government, its influence on business activity and its failure to protect intellectual property rights

- The Chinese education system, with its brutal regime of exams and focus on rewarding high test scores rather than creative thinking.

But despite these reasons (or perhaps because of them), China’s governments, universities and businesses are embarking on a major innovation drive, determined to become a world leader in what they describe as mass innovation and mass entrepreneurship. Massive incubators are being built and subsidised and new policies implemented: such as that announced in 2016 that will allow students to break their university studies at any point in their degree programme and start a business, with the understanding that their university must take them back at the point where they left – either if the venture has failed or has been so successful that the entrepreneur has sold it and wants to return to their studies.

Certainly, there is no lack of confidence among young Chinese people that they can lead the world in innovation. In August 2016, I asked an audience made up of academics from all over the world to fill in a questionnaire, including the question: What is the world’s most creative country? Over 50% wrote “the United States”. Nobody wrote China. When I asked the same question in Beijing in September 2016, nearly 80% of Chinese students answered “China”.

It is certainly true that if you spend time in China you see innovative start-ups popping up everywhere. One such is Ofo Bikes, which has been labelled China’s Uber for bicycles, but this is a label that likely undersells what Ofo does.

Started at PKU (Peking University) in Beijing by a group of the university’s students and graduates, Ofo enables university students to use a WeChat app to rent a low-tech bike to cycle across their typically massive and flat campuses as they race between their classes or social engagements.

Ofo has a ready supply of low-tech bikes to recycle. Every year Chinese students leave their bikes behind them as they are cheap and difficult to bring on public transport. These are then gathered into university bicycle graveyards, where they will eventually become landfill.

Refurbing such bikes and then spraying them with the distinctive Ofo yellow, the company amps up the low-tech look. Flat, short rides means no need for gears or comfy seats. You can hear the distinctive rattle of an Ofo bike as it comes up behind you on PKU’s shared pedestrian and cycle pathways.

Much of the cost of running a rental bike service comes in maintaining the docks the bikes are slotted into – so Ofo reduces the tech further and does without docks, favouring instead simple combination locks. Send a message with the code number of the bike you want to rent and the combination is sent back to you immediately (these combinations change over time). Your Ofo account on WeChat is then deducted a few yuan.

Another major cost of rental bikes is gathering up and returning bikes back to key locations. Because Ofo bikes can only be used on the campus they are designated to, the bikes don’t go wandering and can be redistributed and otherwise maintained by Ofo’s little three-wheeler motorcycles (see below). Keeping the bikes on campus is helped by the fact that China’s large urban universities are mini walled cities with only a few gates manned by security guards who ask for ID – anybody seeking to make a break on a canary yellow bike is going to stand out! And while campuses here are walled and flat, they are massive (PKU has over 50,000 students; Tsinghua University next door has 75,000); university timetables are tight, and the time between classes short, so being able to grab a bike directly outside a lecture (no docks remember) and ride it to the next lecture theatre on your schedule is well worth the few yuan and a bone-shaking ride.

Ofo already has other competitors, higher-tech sleeker bikes like Mobike, but Ofo’s rattlers are by far the cheapest – and, subsequently, the most popular on campuses.

Ofo has recently been taken under the wing of Chinese ride-sharing giant Didi (which has recently seen off Uber to dominate the Chinese car-sharing industry). Didi sees the potential in the Ofo model, and investment and expansion plans are afoot. The first targeted overseas beachhead for Ofo is the British university and science-park dominated city of Cambridge. Soon some of the West’s most creative minds could be riding an innovative business model developed by some of the East’s.

Source: Opening quotation taken from “Why China can’t innovate” by, R.M. Abrami, W.C. Kirby & F.W. McFarlan, Harvard Business Review, March 2014.

8-3 M-Pesa: Innovation Out of Africa

Denno Abisai was surprised at how difficult it was to pay for things when he arrived in New York in 2012. He either had to find and carry cash, use a credit card and provide a lot of personal details, or arrange payment terms. Back in Nakuru it was so much easier. Denno and most of his friends and family paid for most daily items, from a loaf of bread to a soda to rent, with their mobile phones.

Such payments were facilitated by an innovative Kenyan initiative called M-Pesa (M stands for mobile, and pesa is Swahili for money). M-Pesa, a cell phone-based money transfer and microfinancing service, was launched as a joint venture in 2007 by Vodafone Kenya, Safaricom and Vodacom, Kenya’s largest mobile network operators.

The service allows customers to deposit money into an account stored on their cell phones, to send balances using PIN-secured SMS text messages to other users and stores, and to redeem deposits for regular money or goods and services. Customers are charged a small fee for sending and withdrawing money using the service. In addition to providing a quick and simple way of paying for goods and transferring money, M-Pesa also functions as a branchless banking service as customers can deposit and withdraw money from a network of agents that includes airtime resellers and retail outlets acting as banking agents.

The speed and convenience of using M-Pesa in a country where bank branches are few and far between and the sun is hot (meaning that people don’t want to be lingering to discuss terms of payment with every shop-keeper) is easy to see if one spends time in East Africa. In fact, it has been claimed that M-Pesa’s world-leading innovations in mobile payments can be related to an East African approach to innovation called Jua Kali (which literally means hot sun – as in people don’t want to stand in the sun so they look for new ideas and solutions that enable people to move on quickly!).

The idea behind M-Pesa was born in 2002, when researchers at Gamos and the Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation, funded by Department for International Development UK (DFID), found that people were using mobile airtime as a proxy for money transfer. Kenyans in particular were transferring airtime to their relatives or friends who were then using it or reselling it. Gamos researchers approached MCel in Mozambique, and in 2004 MCel introduced the first authorised airtime credit swapping – a precursor step towards the development of M-Pesa. The idea came to the attention of, and was discussed by, the Commission for Africa, and DFID introduced the researchers to Vodafone who had been discussing supporting microfinance and back office banking with mobile phones. They began to discuss how a system of money transfer could be piloted in Kenya, the largest market in East Africa.

At around this time (2005), a student from Moi University in Kenya developed a mobile software solution that could allow people to send, receive and withdraw money from their mobile devices. Safaricom, recognising the potential of this software in the light of emerging ideas in the sector, bought the patent rights from the student and sponsored a student software development project in Kenyan universities to develop and refine the technology. In April 2007, Safaricom joined with Vodafone to launch M-Pesa.

M-Pesa became very popular very quickly, to the extent that Denno and his friends in Kenya struggle to remember a time when they used to use cash to pay for things (although Denno is “relearning” how to use cash now he is living in America). By 2012, there were about 17 million M-Pesa accounts registered in Kenya. And by June 2016, 7 million M-Pesa accounts had been opened in neighbouring Tanzania by Vodacom. M-Pesa has also since expanded to Afghanistan, South Africa, India, Romania and Albania. Since 2010, it has become the most successful mobile-phone-based financial service in the developing world and the service has been praised worldwide for giving millions of people who were not connected to a banking system access to financial services and for reducing crime in what were previously largely cash-based societies.

8-4 Evandale Gardens: Rhubarb, Rhubarb

The world’s southernmost market garden plant production nursery is Evandale Gardens. Locally owned and operated, Evandale was established in 1930 in Invercargill, a small centre at the southern edge of New Zealand’s South Island. While small, Evandale prides itself on its industry knowledge and its relationships with retail garden centres throughout New Zealand. Its “Moulin Rouge” rhubarb plant, with its unique ruby-red stems, is considered to be one of world’s finest varieties.

Rhubarb plants adapt over time to suit local conditions as they propagate and so commercial varieties may not have the qualities that local home-grown varieties have. Moreover, rhubarb is unusual for a vegetable in that it is a perennial, coming back every year at the same time wherever you plant it. It is not known how old the world’s oldest perennial plants may be, but some gardeners claim to have plants that are over 100 years old. Hence, some of oldest plants may now be quite unique and the best varieties may be lost in back gardens around the world.

In 2016, Evandale launched “The Rhubarb Challenge”. It called on New Zealand’s home gardeners to send in a winter rhubarb crown, and if this plant was considered to be worthy of market development the owner would be given a cash prize. “What we are after are the potential heritage type varieties that can sometimes be hidden in old home gardens,” explained Evandale’s General Manager Nathan Piggott. “Some of these have great flavour and vigour.”

While this is not the first open-innovation drive, it is, at the time of writing, the first one that we are aware of directly related to rhubarb!

8-5 Jersey Postal: Check’s in the Post

There may be no market that so classically meets the definition of “mature” as postal services (a.k.a. “snail mail”). Conduct an ESTEMPLE analysis as we outlined in our Macro-shocks chapter and you would see any number of environmental forces against it: technological, social, environmental, economic … the list goes on. Look at an industry life cycle framework and there would be little doubt that post has gone way past mature and into decline.

But one postal service has thought of an innovative way of seeking to turn that seemingly inevitable decline into a “dolphin tale”. While many analysts have seen the expensive process of delivering letters to homes as a major weakness that traditional postal providers need to move away from, and the fact that the main customer group that still prefers to receive mail through the letterbox is an ageing population has been seen as a major threat, Jersey Post has sought to turn this thinking on its head. What if going door-to-door in person was a strength and the elderly an opportunity to innovate?

This idea has led to the trialling of a new product line for Jersey Post called “Call & Check”. One of the major social problems associated with an ageing population is that elderly people can become isolated in their homes. Many do not want, or cannot afford, to move into elderly care, but they would still benefit from the reassurance of regular visits, reminders from someone they know to do certain things (like taking medication, or changing batteries on smoke alarms). A little help around the home, or having grocery items delivered would be a godsend.

Sometimes the postie is the most regular visitor to an elderly person’s home. So, in recognising this and the needs outlined above, Jersey Post can now provide regular “check ins”, daily, weekly or as agreed. Postal staff can have brief conversations with the resident to ascertain how they are and if they need anything, or they can provide standing orders in consultation with customers or their designated contacts. While Jersey Post cannot provide medical care, they can provide a regular, friendly face that frequently calls and checks, and can provide almost any other form of necessary help and support and raise concerns with appropriate authorities and other carers where necessary.

It is early days as to whether this new service will prove a success, but it is proving extremely popular in Jersey, has created a lot of good publicity for Jersey Post and has attracted attention from other postal service organisations around the world.

Could a maturing population hold the key to de-mature this industry?

Writing your own “new ventures” case

Writing your own “new ventures” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “the Mini Case” and “the Briefing Note”, guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and this is a good vehicle for that purpose. There are also a large number of websites that highlight interesting organisations that you might want to find out more about. For instance:

- websites for national newspapers

- Forbes

- TechCrunch

- uk.businessinsider.com

- www.fastcompany.com

- www.huffingtonpost.com.

It is also worth noting that in the UK there is an excellent website for company information at Companies House. The address is https://beta.companieshouse .gov.uk/.

One of the advantages of writing about new ventures is that there is generally a lot of press commentary on what is new and upcoming, particularly in the tech sector. However, don’t overlook local businesses that can be doing something innovative near you. Particular entrepreneurs are the modern rock stars of the business world, so you can also follow the personality as well as the organisation to try to understand how has it become successful, or why their latest venture may become successful. Indeed, this might be the time to write a case about your own business idea and see if it flies.

In terms of other types of expansion, there is a great deal of information easily available about Mergers and Acquisitions. These excite a lot of media commentary that presents a rich source of data for you to use, both in quantitative and qualitative terms. Strategic alliances are not reported to the same extent but, again, the larger ones do receive reasonable coverage in the media. However, keep remembering to ask: “what is the strategic question that is being asked here?”

![]()

Notes

- 1. Keeley, L., Walters, H., Pikkel, R. and Quinn, B. (2013) Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs, John Wiley & Sons.

- 2. Sawhney, M., Wolcott, R. C. and Arroniz, I. (2006) The 12 different ways for companies to innovate, MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(3): 75.

- 3. Bilton, C. and Cummings, S. (2010) Creative Strategy: Reconnecting Business and Innovation, John Wiley & Sons.

- 4. Croll, A. and Yoskovitz, B. (2013) Lean Analytics: Use Data to Build a Better Startup Faster, O'Reilly Media, Inc.

- 5. See Angwin, D. N. (2007a) Mergers and Acquisitions, John Wiley & Sons, for a review of strategies for M&A. Also, see Angwin, D. N. (2012) Typologies in M&A research, chapter 3 in Faulkner, D., Teerikangas, S. and Joseph, R. (eds), Oxford Handbook of Mergers and Acquisitions, Oxford University Press, for a review of M&A typologies used to classify M&A strategies. These are developed further in Angwin, D. N. (2007b) Motive archetypes in mergers and acquisitions (M&A): The implications of a configurational approach to performance, Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, 6: 77–106, which seeks to indicate performance links. However, later work by Angwin, D. N., Paroutis, S. and Connell, R. (2015) Why good things don't happen: The micro-foundations of routines in the M&A process, Journal of Business Research, 68(6): 1367–81, indicates there are many influences that may cause acquisition strategies not to work out.

- 6. Haspeslagh, P. and Jemison, D. (1991) Managing Acquisitions, Free Press; Larsson, R. (1990) Co-ordination of Action in Mergers and Acquisitions, Lund University Press: 44.

- 7. Angwin, D. N. and Meadows, M. (2015) New integration strategies for post acquisition management, Long Range Planning, 48(4): 235–51. Even within these dominant integration strategies there are further complexities – see Angwin, D. N. and Meadows, M. (2013) Acquiring poorly performing companies during economic recession: Insights into post-acquisition management, Journal of General Management, 38(1), Autumn: 1–24.

- 8. Angwin, D. N. and Vaara, E. (eds) (2005) Connectivity in merging organizations, Special Issue, Organization Studies, 26(10), October: 1447–635; Gomes, E., Angwin, D. N., Weber, Y. and Tarba, S. (2013) Critical success factors through the Mergers and Acquisitions process: Revealing pre- and post-M&A connections for improved performance, Thunderbird International Business Review, 55(1), January–February: 13–35. Not only is it important to take into consideration the critical linkages, but also that the speed of integration can make a fundamental difference to outcome – see Angwin, D. N. (2004) Speed in M&A integration: The first 100 days, European Management Journal, 22(4): 418–30 and Bauer, F., King, D. and Matzler, K. (2016) Speed of acquisition integration: Separating the role of human and task integration, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 32: 150–65.